#Khandrel

Text

Asker: @lumiere-angel-90

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

And a time for planting (that which was uprooted)

Trigger warnings for mentions of death and descriptions of grief and depression.

An ending comes to Ixil and Grór’s story (or the start of a new one). My headcanon, inspired by the fantastic @mrkida-art

4/4

2.6k words

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 3.5

—

Ixil,

The pen stalls, then falls.

Grór sighs, screwing up her face in concentration, against a headache that cleaves her skull.

I did not receive a reply to my last letter. I hope all is well in the East? Let me know.

Ulri died—

She can’t go on, and she places the pen down harshly. It clatters against the metal ink well. She picks it up.

The stone-setting will be soon.

She cannot bring herself to write any more details. That would be enough — if he even bothered to respond this time. She passes the parchment into the hands of a servant without sealing it and folds back down over her writing table. Somewhere behind her, a child cries.

Far away, another dwarf sits in a writing chamber. The winter in Ugzharak has been particularly harsh this year, and blizzards rip across the tundra outside of the Stiffbeard hold.

The rebuilding — seven years hence the remnants of the dragon was found — grinds on stalwartly. Ice had spread into much of the interior, cracking and weathering millenia of stone halls and supporting structures; for dragons are not well known to close the door behind them once they entered a dwarf’s lodging. Other foul creatures followed. Tribes of Men, followers of the Zigûr and goblin-friends, had sneaked in and set up camp unnoticed. Hall upon hall, home upon home were ransacked, the metalwork stripped and plundered. Filth, decay and rot littered once habitable dwellings, mouldering on top of a thick covering of ash and dust.

Ixil’s first task, once he had arrived in Ugzharak, had been to lead a party of warriors inside the lower levels and secure them of hibernating beasts. Some were killed quietly by a well timed crossbow bolt; others were wide-awake in ambush, and a fully grown adult whitebear could kill three dwarves in one swipe of its torso-sized paw.

It was tiring, gruesome work as they relentlessly scoured the forgotten streets of their ancient home. Dwarves who were now grown and under Ixil’s command had not even been born in Ugzharak, knowing only Thikil-gundu, and a few greybeards had to lead the way down mazes of corridors and backalleys, as Ixil’s own memory had grown hazy with the passing of years. His heart had ached as he encountered unfamiliar stone, tracing it questioningly with soot-blackened fingers, but his stonesense received only pain and anger in return.

You abandoned us, said the stone. You left us to die.

The bodies of the dead dwarves were the worst to come across, and it has taken a full sun-cycle for Ixil’s beard to recover from the amount of times he has shorn it. Now, he is more used to having stubble on his cheeks than a proud braid falling from his chin. Some parts of Ugzharak he still cannot enter, for fear of the memories it stirs up inside him. Bodies upon bodies. Some cowering, some small — of children. He can’t go into those parts, even after they were cleansed by khandrel and the sacred dances of death had been danced by the zhanim. They couldn’t cleanse his own mind of what he had endured.

Life is constant in the North-East of Middle-Earth, though the dwarves of Erebor think it grinds to a halt, furling up like a green leaf in the snow. The dwarven nomads return to the Old Ways; some who moved to the greener pastures around Ghomal in the wake of the dragon now drive their shaggy auroch and mumak upland, and join with those families who stayed on the plains out of sheer grit. Stiffbeards sink into industry: ghaspar and coal mining, iron-working, shipping vast quantities of goods across to the cities of Men in the far-reaches of the frozen plains for whale-fat oil. And for Ixil, it seems that he has been barely able to catch his breath. With the election of a new Queen, divined by the omen-speakers of all the Clans, he has risen through the ranks like a fish being hauled up from the deeps. Most of the time, he feels like a fish — hooked and speared, pulled this way and that, gasping for air.

Ixil looks up at Zurkuh, who has a crumpled letter in one hand.

“My Lord…”

He is a Lord now — Scoutmaster for the Queen. Titles don’t suit him well, and neither, he feels, do this many responsibilities. He looks down at the map that he is outlining. A pack of snow-orcs were sighted in the middle of one of these foul blizzards, driving a large herd of whitebears along one of their traderoutes. He is beginning to suspect, as the omen-speakers have been telling him, that these weather patterns aren’t natural formations of Middle-Earth, but some abominations of the enemy. Ixil rubs his face and blinks hard.

“What is it, Zurkuh?”

His assistant approaches cautiously and then drops the letter in his hand. He only has to say a few words to snap the dwarf from his thoughts.

“It is from the Iron Hills, my Lord.”

—

Ixil’s eyes scan the words in front of him, horror slowly welling inside him. He slams it down on the table, and then, with shaking hands, rips the drawer from underneath him open.

“Where is it? Where is it?” he mutters frantically, and then turns to Zurkuh who is standing by silently.

“Did I write?”

“My—”

“Did I write?” he forces himself up from his chair and crosses to the slender dwarf, taking his shoulders in his hands. He forces his breath to come slower, but the panic doesn’t abate and his speech makes little sense to him.

“Do you remember? This year — this Durin’s Day? If I wrote?

Tell me, Zurkuh, tell me that I did. Tell me I did not forget. I write, I always write—

Zurkuh shakes his head sadly.

“The last time you wrote to the Iron Hills was five years ago.”

Ixil blinks.

“No— no it cannot—”

He returns to the desk and throws piles of parchment onto the floor around him, and they scatter like leaves at his feet. His hands pause somewhere near the bottom of the drawer and he picks up a precious piece of paper as though it is edged in gold leaf. Near the top of it, in Grór’s spidery handwriting, is the date he received it, and his finger traces the runes around and around.

Five years before. Five years. He had forgotten to write for five whole years.

Slumped in his chair once again, he feels numb. Zurkuh moves behind him and picks up the fallen letter that had fluttered from his desk, placing it on top of the map once more.

“Friends grow apart,” he says softly.

—

No words were spoken at their parting. Formalities only. Avoiding glances, and then catching one another’s eye only to look away again. There was so much to do that it was easy for them to ignore one another — until they couldn’t.

Ixil looked down at Grór’s hands over his. His blood thundered loud in his ears — what was it… embarrassment, sadness, guilt? — and his throat constricted, trying to force something out, but there wasn’t any more time to speak to her.

“Write,” she said.

“I will visit — I will come back,” he said, his chin rising in defiance. But even then, he knew that was a lie. Grór grimaced. The ugly truth lay naked before them. No — this was it. The end, and the beginning of something new — this time, without the other.

—

“It is good to have you to watch with, as well. I might mistake everything for a dragon, but know that I’ll be ready to fight it, if one comes. You Longbeards took me in. I vow to defend your home until I lose my legs or my breath doing so.”

—

“I took an oath,” the Stiffbeard says to himself. Disgusted, he looks down at the last letter, the one Grór sent five years ago. He remembers now, saying that he would put pen to paper, and then that he would go himself on occasion of her marriage, and how he would choose a wedding gift that would eclipse all others: a crown fashioned out of pearls and white gold, with the three-headed mumak on it, the same one that she wore in iron at her breast.

If she still wore it.

And then… he struggles to remember, memories of even last week fogging up like steam in front of his eyes. And then— that had been the year that the hold had almost starved, with trading from the south blockaded by war.

So he hadn’t written, after all.

“It doesn’t matter,” his own voice replies.

An oath of seventy years past doesn’t matter? What would his mother say to him if she could see him now? If she had survived the journey back?

Don’t start something and not finish it.

Zurkuh has procured him a fresh sheet of paper from somewhere and a pen. The other one has rolled away underneath the desk, and the ink bottle tipped over. He presses them both into the Scoutmaster’s hands and sets them on the paper.

“Even so, it is best you write back. I can arrange a funeral gift to be sent. You have enough to do, Lord.”

Was he even a Lord anymore? There was nothing lordly, nothing noble about a dwarf abandoning his kin. But still, he could write back. He could do this one thing.

He wrote one rune, and then another. The first two rune-letters of the date. His hand stilled.

“Bring me my cloak,” he said. When Zurkuh didn’t move, he stood up himself and brushed past him to his bedroom, fearful that if he stopped for a moment to reconsider his actions, the sensible part of his heart would take over.

“Where are you—”

“And pack a sled for me,” he said, turning to face his assistant, “for a journey to the Iron Hills. I am going there myself.”

—

The fog of depression settles deeper into Grór’s bones. With each passing day, she feels it gnawing its way in like ants on a log, hollowing her out from the inside.

Yesterday, Frór and Thrór arrived, but there had been no welcoming party to greet them. It was all that she could do to stand when they entered her chambers. Frór went straight to Nain’s room and emerged with him in his arms.

“I’ll bathe the wee one,” he said quietly, as he went to fill a kettle of hot water. Nain blearily blinked up at his uncle before falling asleep again, his small fingers wrapped in his straw-coloured hair. Thrór had simply sat in silence. Then, when it was evident that Grór would not speak, he had returned with a cup of something hot and set more coal to the fire, prodding it until the room grew warmer.

“You need to eat,” he said, bending down to peer into Grór’s face. She hardly saw him.

—

The morning dawns. It could be morning or it could be evening for all the Lord of the Iron Hills cares. It is the same to her, and sleep comes in fitful bouts when she passes out in her room from exhaustion. At least this morning she manages to sit on her throne and her breakfast doesn’t make her nauseous. She eats half of the porridge before it grows thick and cold, and eventually someone takes it away.

The door to the kitchen swings shut behind the dwarf at the same time that another one opens across the Great Hall. The raises her eyes to the messenger that strides quickly towards her. Something about his confused expression makes her sit up a little straighter.

“Yes?” she asks, before he has time to reach her. He bows, and then, as if at a loss for words, gestures behind him.

“My Lord Grór, there is a visitor…”

There have only been visitors this past week, the week before the stone-setting. She icily reminds the messenger such. He stammers an apology.

“The dwarf is from the East — from Ugzharak, Lord. He’s pulled his sled right outside and says he knows you, but we had no word of his coming at the watchtower, so—”

The doors smash open with enough force to shake the floor. A dwarf in tattered, weather-stained clothes and boots marches in, barely restrained by two guards.

“Grór!” he shouts, before the guards seize him by the wrists. He’s too deft for them and escapes their clutches with the dexterity of a weasel. Before they have time to draw axes, he’s running towards her, his eyes wild and his face flushed from the cold. Grór sees a flash of it before he throws himself onto one knee before her, a brown, scarred hand reaching forwards for the tip of her boot.

“I came back.”

The guards drag him up and away, pulling at his cloak which rips from his shoulders. And finally, Grór finds her voice.

“Stop—” she rasps.

They stand, facing one another in silence. A letter falls to the floor — the one she had written just a few weeks ago.

“I told you — Grór, I said I would visit,” he says, his eyes pleading with her.

It has been seven years.

She wants to hit him, to push him away, to scream at the guards to take him from the Hall at once. But, she soon realises, she doesn’t have the energy. The anger that she might have held seeped from her weeks ago, along with her joy. All she can do is stare. And then Ixil is close to her, and his hands are over hers. His fingers have more callouses now, and they feel harder and stronger, while hers are tattooed in dark ink and stripped of all her customary rings and ornamentation. Between her breasts, she feels something, as though another heartbeat had stirred next to her own. Something she hadn’t thought of for years, but had worn, unnoticed, next to her skin. A small, iron trinket.

“Idu’bar,” he whispers, so quietly that it feels as if her own soul is muttering the deep name which few in her life have ever known. “I have come back.”

Epilogue

“We’ve had our troubles,” she says.

Ixil nods and licks the foam from his top lip. Grór sinks back in her chair, and for the first time in countless weeks, feels full. Ixil, on the other hand, is still eating chicken leg after chicken leg, until Grór supposes that he’s eaten a whole flock.

“The East is a… troubled place of late,” he replies delicately. He looks at her enquiringly. “I would still like you to see it.”

“Perhaps I will,” she says.

Before now, she would have thought that impossible. But today she has discovered many things. That in the eye of grief’s storm she can smile, and smoke a pipe in peace, and eat a full meal. That a dwarf she thought long gone could spring up out of nowhere like new grass and pull a sled halfway across Middle-Earth to be with her. Why could she not venture out and see new sights, and explore new things again?

There was a place and a time for everything. For death and for life renewed.

End.

Kh. Idu’bar (id-u’bar): Grór’s deep name of my own invention (grower); apparently Grór could be derived from the Old Norse gróa, meaning ‘to grow’. It also means ‘to heal’.

#tolkien#gror#dwarves#tolkien fanfiction#lord of the rings fanfiction#the lord of the rings#middle-earth#the hobbit

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Askers:

@ask-gadzooks

@jameshoppy

@lumiere-angel-90

@smrtz

@flashtheponyofwind

#MLP#MLP Art#MLP Ask Blog#ask-gadzooks#jameshoppy#lumiere-angel-90#smrtz#flashtheponyofwind#Story#Update#Khandrel

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Askers: @ask-the-prototypes @ask-gadzooks

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Askers: Anonymous

24 notes

·

View notes

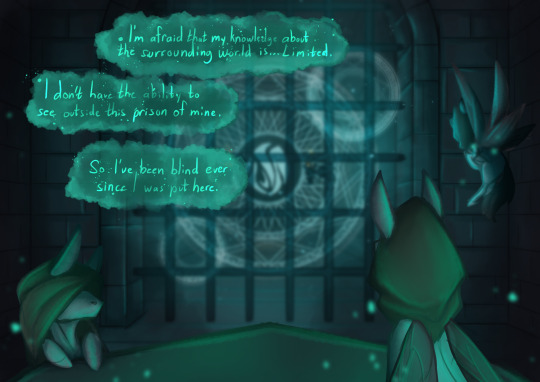

Text

Follow the journey of Khandrel, and have the ability to help or even sabotage events to come. Remember that what you as the Askers say and do can do harm to the characters, both directly and indirectly.

This world's setting is a Medieval-esk Fantasy one fully separate from the MLP Show's world. This means no characters within the show exists within this universe and therefore are unknown.

DISCLAIMER: This blog deals with Dark and Sensitive Themes. These themes include subjects such as trauma, violence and oppression. Tags will be made for the different subjects and community labels will be used when appropriate.

The opinions of characters and the setting at large does not reflect the opinions and thoughts of the one running the blog. Remember that this blog is purely fictional.

If I have failed to tag something, or you wish for a specific trigger tag to be added, don't hesitate to contact me and I'll see if I can add it.

Current Warning Tags:

N/a

About | F.A.Q. | You, the Askers | Khandrel's Profile

9 notes

·

View notes