#Leonor of Navarre

Text

"In total, Leonor governed Navarre as lieutenant, with some minor hiatuses, from 1455 to 1479, making her the effective ruler of the realm for nearly twenty five years. Out of her female predecessors, only Juana I served a longer period; however, Juana I was detached from the governance of the realm and physically distant from Navarre. Leonor however, remained in the kingdom throughout her lieutenancy, making her the female sovereign with the highest record of residency in Navarre.

One of the enabling factors for Leonor’s constant presence in the realm was the “Divide and Conquer” power-sharing mechanism that she employed with her husband, Gaston of Foix. Blanca and Juan had a similar division of duties, but unlike her parents’ often contrary objectives, all of Leonor and Gaston’s actions can be seen to be working toward their joint goals of obtaining the Navarrese crown and politically dominating the Pyrenean region. In order to achieve their ambitions, the couple were adept at working as a team even when physically seperated or carrying out divergent duties.

Politically, it appears that they took on different areas of negotiatiion. Gaston was the designated emissary to the French court, which was entirely appropriate as one of the French king’s leading magnates. One important example of his involvement in negotiations of this type include Gaston’s visit to the French court in the winter of 1461–62 to negotiate the marriage between their heir and the French princess, Magdalena, which ensured Louis XI’s backing for Leonor’s promotion to primogenita. Gaston also conducted negotiations on behalf of his father-in-law, Juan of Aragon, with the King of France, with a successful outcome in the case of the Treaty of Olite in April 1462, which was intimately connected to the marriage that Gaston was orchestrating for his son and Magdalena of France.

Even though Gaston normally took on the role of intermediary with the French crown, there are two letters issued by Leonor during her marriage in December 1466 as lieutenant of Navarre that show her involvement in French affairs. These letters were written during a period of extreme crisis, when Juan II’s difficulties in Catalonia were matched with Leonor’s continuing struggle with the Peralta clan in Navarre. In these letters, Leonor was playing on her familial connection to Louis XI, in hopes of his aid and backing, asking him to “commend this poor kingdom and the said princess to him [Louis XI] as one who is of his house.” Moreover, these letters show Leonor’s independent interaction in crucial diplomatic negotiations with France, both in receiving embassies directly from Louis and in sending her own personal ambassador, Fernando de Baquedano, with detailed instructions on how to proceed.

Gaston appears to have been more engaged with marital negotiations for their numerous offspring than Leonor. However, this may be due to the fact that the couple overwhelmingly chose French marriages for their children. Only three of Leonor’s children did not contract a French betrothal: Pierre who became a cardinal, a daughter who died young, and Leonor’s youngest son, Jacques (or Jaime), who married into the Navarrese nobility. Given the fact that Gaston was more intimately connected to the French court and the nobility of the Midi, it seems reasonable that he would take on the role of chief negotiator for these matches. All of the marital arrangements for their children were made in order for Gaston and Leonor to achieve their joint goals, the acquisition of the throne of Navarre and the consolidation of their power and influence in the Pyrenean region.

Another area where Gaston necessarily played a more central role was militarily. Robin Harris acknowledges Gaston’s successful military career and notes that after his useful military service to the French crown, “the comte was permitted by the [French] king in the last years of his life to employ his military resources in order to further his family’s interests in Navarre.” Gaston also performed many military services for his father-in-law; the agreement of 1455 that promoted Leonor and Gaston to the successors of the realm required Gaston to go to Navarre on Juan’s behalf and retake those areas that had fallen to the rebels “for the honor of the King of Navarre as well as for his own interests and those of the princess his wife."

However, there is some evidence for Leonor’s involvement in one military foray. In the winter of 1471, Leonor took part in a daring attempt to seize the capital, Pamplona, from her opponents, the Beaumonts. Leonor participated in an attempt to storm one of the city gates with a group of armed supporters. Moret notes that “this surprise was reckless; for it exposed the person of the princess to obvious risk and was somewhat rash.” Moreover, the element of surprise was ruined by the cries of her supporters shouting “ Viva la Princesa !” which alerted the Beaumont troops to the threat, and Leonor and her supporters were swiftly ejected from the city.

Like her mother, the noted peacemaker, Leonor was also involved in moves to reduce the civil discord in the realm. Zurita credited Leonor with “making a great effort to resolve the differences of the parties and subdue the kingdom into union and calm.” Leonor represented her father in negotiations for a truce with the supporters of the Principe de Viana on March 27, 1458, at Sang ü esa. Zurita notes, “The princess Lady Leonor was there at that time in Sangüesa and signed the treaty with the power of the king her father.” Leonor was instrumental in the forging of another truce that was contracted in Sangüesa, in January 1473, and she was also present at a conference with her father and her half-brother Ferdinand in Vitoria in 1476 “accompanied by the nobility of Navarre to renew the treatties . . . and attempt to arrive at a stable peace.

Although both spouses were named to the lieutenancy of Navarre, the documentary evidence clearly demonstrates that Leonor appears to have taken on the bulk of the administration of the realm. This was entirely appropriate as it was Leonor, not Gaston, who had the hereditary right to the crown. Moreover, it was logical for Leonor to remain in Navarre so that her husband could look after his own patrimonial holdings and continue to serve as a military commander for the King of France.

Leonor was an active lieutenant but she struggled to implement her rule fully across the kingdom, as many areas were dominated by the Beaumont faction who were opposed to her and her father Juan of Aragon. This meant that at times, she had no control or access to certain key cities in the realm, including the capital, as mentioned previously. Her grandfather’s impressive seat at Olite was the center of her sister’s court, but Leonor eventually regained her hold on the castle and used it as one of her primary residences between 1467 and 1475. Sangüesa remained an important base for Leonor, and she was also associated with Tudela on the southern edge of the kingdom.

Leonor’s difficulty in implementing her rule across the whole of the kingdom is illustrated by a prolonged struggle between the lieutenant and the town of Tafalla, which consistently refused to send representatives when she called together meetings of the Cortes. Tafalla was a center of Beaumont strength, which had supported her brother Carlos in his struggle with Juan of Aragon and was thus bitterly opposed to her appointment to the lieutenancy. Between 1465 and 1475 there is a series of missives from Leonor both summoning representatives from the town and then expressing disappointment when they failed to arrive. During this period, Leonor appears to have called a meeting of the Cortes at least six times, but the town consistently refused to send envoys to the assembly. There is a sense of increasing exasperation and anger in these documents at the repeated failure to participate in these important events. At one point, in late 1471, Leonor personally came to the town to give advance notice of her intent to call another Cortes the following summer, perhaps to circumvent any excuse that the town did not have sufficient time to send representatives, but Tafalla still did not participate in the assembly.

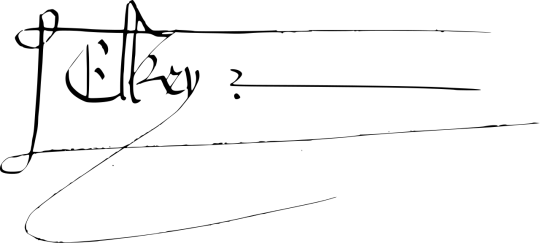

As her authority was contested, Leonor was keen to stress her agency and her position in the documents that she issued. However, at times she even struggled with the chancery; between 1472–73, Juan de Beaumont retained the seals of the kingdom and refused to let Leonor have access to them. In 1475, she granted a reduction in taxes to the important city of Estella acknowledging the reduced capacity of the city to pay after the population had shrunk from the effects of war and flooding. In this document she stressed her efforts to assist all of the urban centers of the realm, to help them recover from the years of civil conflict and devastation, “the other good towns of the said realm have been refurbished by our certain knowledge, special grace, our own change and royal authority.

Leonor’s address clause drew on all of her family and marital ties as a means of establishing her authority:

“Lady Leonor, by the grace of God princess primogenita , heiress of Navarre, princess of Aragon and Sicily, Countess of Foix and Bigorre, Lady of Bearn, Lieutenant general for the most serene king, my most redoubtable lord and father in this his kingdom of Navarre.”

The signet that Leonor used for the majority of her lieutenancy as well as her sello secreto had heraldic devises that mirror her address clause, bearing the arms Navarre, her family dynasty of Evreux, her husband’s counties of Foix, Béarn, and Bigorre, and finally the Trast á mara connections to Aragon, Castile, and Léon.

To sum up, Gaston and Leonor’s ability to divide up roles and responsibilities demonstrates the couple’s effective partnership, using each partner in the most appropriate arena. Moreover, this division was entirely necessary as the couple’s widespread territorial holdings and the demands of balancing the complicated and difficult political situation both within Navarre and the Midi and between France, Castile, and Aragon meant that both partners needed to be fully engaged and active in order to achieve their mutual goals and further their dynastic interests.

Even though Leonor and Gaston generally employed this mode of “Divide and Conquer” that left Leonor primarily responsible for the administration of Navarre while Gaston oversaw his own sizable patrimony, the couple did work together as a unit whenever possible. Documentary evidence shows that Gaston came to stay with Leonor in Navarre for short periods, particularly during the autumn of 1469 and 1470. There is also some additional evidence to indicate an earlier reunion in 1464, which appears to indicate a desire on the part of the couple to be together. Gaston and his party were stuck in the mountain passes between Foix and Navarre on his way to visit Leonor. The princess issued a series of orders to dispatch men and pay for additional recruits and mules in the mountains in order to clear the passes and roads for Gaston, including one order for 300 men to be sent to help. Gaston’s death in 1472 took place on another journey to see his wife in Navarre; he died en route of natural causes in the Pyrenean town of Roncesvalles.

Overall, Gaston and Leonor worked together with the mutual goal of obtaining the crown of Navarre, throwing the weight of Gaston’s power, wealth, connection, and military forces behind Leonor’s hereditary rights and were willing to fight off opposition from their own family in order to succeed. They worked in partnership, with each partner taking on the most appropriate role; Leonor was responsible for the governance of Navarre, and Gaston supported her militarily and financially. They both worked on diplomatic efforts to achieve their ambitions; Gaston used his position as a powerful French vassal and general to gain support while Leonor negotiated with her Iberian relatives to maintain their rights.

[...] Tragically perhaps, Leonor hardly had a chance to enjoy the position of queen regnant when it finally came her way. Leonor’s death, only a few weeks after her father’s in February 1479, meant that her rule as queen lasted less than a month. Leonor changed her address clause to reflect her altered position as “Queen of Navarre, Princess of Aragon and Sicily, Duchess of Nemours, of Gandia, of Montblanc and Peñafiel, Countess of Bigorre and Ribagorza and Lady of Balaguer.” Ram í rez Vaquero points out that most of these titles were disputed; several were titles that should have come to her as part of her paternal inheritance from her father but in reality would have gone to her half-brother Ferdinand de Aragon. In addition, the French titles that Leonor had held as Gaston’s wife had already been passed to her grandson. It appears that Leonor had enough time to mount a formal coronation, on January 28, 1479, at Tudela, firmly establishing herself as Queen of Navarre, even if only for a brief moment. Moret remarked that “out of all the kings and queens of Navarre she was the one who reigned the shortest, although she may have been the one who desired [the crown] most.”

-Elena Woodacre, "Leonor: Civil War and Sibling Strife", "The Queens Regnant of Navarre: Succession, Politics and Partnership, 1274-1512" (Queenship and Power)

#gotta love ruthless ambitious mutually devoted power couples 💅#(they can have a little fratricide. as a treat)#historicwomendaily#Leonor of Navarre#Gaston of Foix#aka the self-declared malewife#Navarre history#Leonor fighting and scheming and waiting for the throne for decades only to finally succeed and then die less than a month later#biggest of Ls honestly#I do wonder what she would have thought about that twist of fate#Was she bitter about the hollow victory of it all?#Or was there nothing but satisfaction that she died as the Queen of Navarre#a position she had fought for for so long#or...both?#(also let's get one loud 'BOO' for Juan the Faithless aka one of the worst historical fathers I have ever read about)#(this is the guy who raised Ferdinand 'I'm going to lock up my own daughter' of Aragon btw. This is where he learned it from)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The betrayal was all the worse for Eleanor’s apparent infatuation with her new husband, although she consented to the marriage in part because it offered a means of escape from her brother’s dour court. Although she was not physically unattractive, at least compared to the other Habsburgs, Francis found it impossible to conceal the repugnance he felt for his new wife. Matters were made worse by the fact that Eleanor, at least in the early years of their marriage, seems to have been highly sexed. Pressed by the Duke of Norfolk in 1533 for an explanation as to why the marriage remained distasteful to the king and why no children had resulted from it, the king’s sister Marguerite proved unusually forthcoming. She told him that, for the past seven months, ‘he neither lay with her nor yet meddled with her’. A further explanation came when she informed Norfolk that ‘When he doth lie with her, he cannot sleep; and when he lieth from her no man sleepeth better.’ Warming to her theme, she added: ‘The queen is very hot in bed and desireth to be too much embraced’, before concluding a damning description of her carnal interest by laughingly comparing her own marital situation, saying: ‘I would not for all the good in Paris that the king of Navarre were no better pleased to be in my bed than my brother is to be in hers.’ It was made clear to Eleanor that her worth, such as it was, was to be no more than a diplomatic conduit between her husband and brother; if she expected more, she would only be disappointed.”

Leonie Frieda, Francis I: The Maker of Modern France

#Leonor de Austria#Eleanor of Austria#Francis I of France#François I#Marguerite of Navarre#Duke of Norfolk#Carlos Rey Emperador

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bastard Kings and their families

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

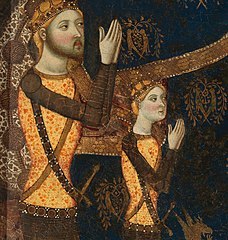

1) Henry II of Castile ( 1334 – 1379), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán; and his son with Juana Manuel de Villena, John I of Castile (1358 – 1390)

2) His wife, Juana Manuel de Villena (1339 – 1381), daughter of Juan Manuel de Villena and his wife Blanca de la Cerda y Lara; with their daughter, Eleanor of Castile (1363 – 1415/1416)

3) His father, Alfonso XI of Castile (1311 – 1350), son of Ferdinand IV of Castile and his wife Constance of Portugal

4) His mother, Leonor de Guzmán y Ponce de León (1310–1351), daughter of Pedro Núñez de Guzmán and his wife Beatriz Ponce de León

5) His brother, Tello Alfonso of Castile (1337–1370), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán

6) His brother, Sancho Alfonso of Castile (1343–1375), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán

7) Daughters in law:

I. Eleonor of Aragon (20 February 1358 – 13 August 1382), daughter of Peter IV of Aragon and his wife Eleanor of Sicily; John I of Castile's first wife

II. Beatrice of Portugal (1373 – c. 1420) daughter of Ferdinand I of Portugal and his wife Leonor Teles de Meneses; John I of Castile's second wife

Son in law:

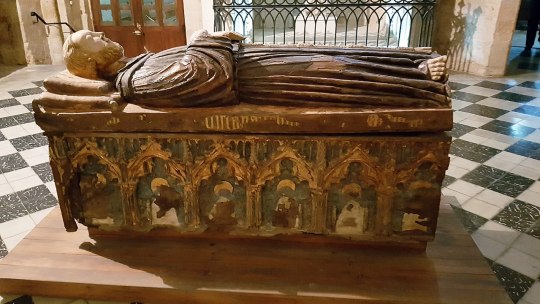

III. Charles III of Navarre (1361 –1425), son of Charles II of Navarre and Joan of Valois; Eleanor of Castile's huband

8) His brother, Peter I of Castile (1334 – 1369), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Mary of Portugal

9) His niece, Isabella of Castile (1355 – 1392), daughter of Peter I of Castile and María de Padilla

10) His niece, Constance of Castile (1354 – 1394), daughter of Peter I of Castile and María de Padilla

#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#henry ii of castile#john i of castile#juana manuel de villena#eleanor of castile#alfonso xi of castile#leonor de guzmán#tello alfonso of castile#sancho alfonso of castile#peter i of castile#constance of castile#isabella of castile#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#day 10#echoes of the past#historical parallels#medieval bastard kings#bastard kings and their families#eleanor of aragon#beatrice of portugal#charles iii of navarre#canonjonsnow

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“I've read someone say that Leonor might have been named after Eleanor of Aquitane, but it is more probable that she was named after Leonor of Austria, (daughter of Joan I and Philip I, sister to Charles I and V) Queen Consort of Portugal and France. There was also a Leonor of Castile who was Queen Consort of Aragon and even a Queen Leonor I of Navarre (who was named after her grandmother) . It would be weird to name her with a French woman in mind, though she was a formidable woman so it's always a possibility.” - Submitted by Anonymous

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen consorts of England and Britain | [22/50] | Eleanor of Castile

Eleanor was Queen consort of England from 1272 until 1290 as the first wife of Edward I. She was born in 1241 as the daughter of Ferdinand III of Castile and Joan, Countess of Ponthieu. Her birth name was Leonor which was Anglicized to Eleanor when she came to England. Eleanor was highly educated, much more so than most women of her generation. In 1253, Eleanor’s older brother hoped to arrange a marriage between her and Theobald II of Navarre however this marriage never came to pass and on 1 November 1254, Eleanor married Prince Edward of England instead. For the first year of their marriage, they lived in Gascony where Edward ruled as Lord of Aquitaine. During this time, Eleanor, aged only about 13 or 14, gave birth to a short-lived daughter. During the Second Barons’ War of the 1260s, Eleanor actively supported Edward and even brought soldiers from her mother’s land in France to help support the royalist army. For a long time it was believed that Eleanor was sent to France during the war, but in fact, she actually stayed in England and even held Windsor Castle and kept prisoners. After Edward was captured after the Battle of Lewes in 1254, Eleanor was removed from Windsor Castle and confined at Westminster Palace. By 1270, the war was over and Edward and Eleanor left to join the Eighth Crusade. While in the Holy Land, Edward was almost assassinated via a poisoned dagger. There was a story that Eleanor saved Edward’s life by sucking the poison from his wound, however this is false. In December 1272, while still on crusade, Edward and Eleanor learned of the death of Edward’s father. They began their journey back to England and were finally crowned as King and Queen consort on 19 August 1274. Unusually for most royal couples at the time, Edward and Eleanor were very happy together and devoted to each other. Although, Eleanor is regarded warmly by history, she was not well-beloved in her own time, however, she did have more political influence than was previously believed. She was also very influential in the arts, particularly literature. She had the only royal scriptorium in Europe at the time. On top of patronizing literature, she also popularized tapestries and carpets and also greatly influenced garden design. Eleanor wasn’t known to have suffered any major health problems during her life, however, after the birth of her last child in 1284, she began becoming increasingly ill. After a prolonged illness, she finally died on 28 November 1291.

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

UNDERRATED RELATIONSHIP/PARTNERSHIP/FRIENDSHIP MEME 7/?: my pick: Juana Enríquez & Juan II of Aragon

The marriage of Juana Enríquez and don Juan of Aragon and Navarre was a political union, derived from a simple political expedience: the necessity to tight the bond between the adversaries of powerful don Álvaro de Luna (who, in fact, ruled in Castile), since he had gotten back in John II of Castile’s good graces. Don Diego Gómez de Sandoval, count of Castro, acted as a go-between between the admiral of Castile (Fadrique Enríquez) and the king of Navarre (Juan of Aragon). Having arranged the marriage and having obtained the consent of Alfonso V of Aragon (Juan’s older brother whom he would eventually succeed), the future spouses got betrothed – they took each other’s hands – at Torrelobatón, on 1 September 1444, in the presence of the king and queen of Castile and the prince of Asturias (future Henry IV). The bridegroom was 46, the bride 19 years old. The age difference emphasized the political nature of the union. The wedding did not take place until 1447. There were two reasons behind this delay: firstly, Rome had to be approached for the dispensation, for there existed the fourth degree of consanguinity between the betrothed, and then, the disaster of the Battle of Olmedo (1445) happened, forcing don Juan of Aragon and don Fadrique to run off to Navarre. The bride, who was already known as queen consort of Navarre, found herself in the custody of John II of Castile, who had taken over Medina de Rioseco. She recovered her liberty on 1 May 1446, thanks to the intercession of future Henry IV, but on an express condition that the wedding with her betrothed would not be celebrated without the consent of the king of Castile. The fire in the village of Atienza, which was supposed to be a part of doña Juana’s dowry, caused another delay of the admiral's matchmaking plans. Finally, John II of Castile gave the desired permission, and the young Castilian woman could receive the wedding ring from the hands of her mature, Aragonese suitor, on 13 July 1447, at Calatayud. Then, the passionate affection stirred in the heart of the Aragonese infante that he bestowed upon his second wife during their married life. According to her contemporaries, doña Juana was a beautiful, intrepid and intelligent woman. She was "charming", according to her adversary, don Pedro of Portugal, although in the pejorative sense of this word: not a charming woman but a deceitful one. It was enough to win the love of her husband. He also showed her paternal affection, for she well could be his daughter. For don Juan she always was his 'little girl’, in the moments of intimate tenderness and in those of political drama.

- Jaime Vicens Vives, Historia crítica de la vida y reinado de Fernando II de Aragón

Although he relied on his lieutenants—Carles, his wife Juana Enríquez, and later their son Fernando—he was discerning and cautious. A complex and contradictory man who was loathe to share power, Juan was infamous both for his reluctance to work with the Catalan ruling elites and his shabby treatment of his son. Carles and Juan had a deeply problematic relationship owing to the father’s unwillingness to relinquish his claim to Navarre in favor of his son, and then disinheriting him in favor of his daughter Leonor, wife of Gaston de Foix. Tensions between father and son worsened when Juan married Juana in 1444, and many of the later political problems in the Crown of Aragon can be traced to personal problems in the royal family. Juan’s miserly attitude toward the Catalans and his son did not, however, extend to his second wife. He endowed Juana with similar powers to those possessed by Maria of Castile, and in many ways she was truly co-ruler with Juan. Throughout her marriage to Juan she was one of his closest advisers and most valuable allies, traveling with him throughout Navarre and the Aragonese realms. Juan relied on her intelligence and discretion, her prodigious familial, financial, and political connections in Castile, and her tenacious and formidable negotiating skills. In 1451 he appointed her Governor of Navarre with Carles, and the next year she gave birth to Fernando, both of which further deteriorated an already troublesome relationship. In 1458 Juan appointed Carles, then thirty-three years old, as Lieutenant General in Catalunya, where he proved to be enormously popular. Juan imprisoned him on trumped up charges of treason, and when he died of tuberculosis in September 1461, accusations of foul play surfaced, accusing not only Juan but also Juana of plotting against Carles in favor of her son, Fernando (1452-1514, later Fernando II of Aragón). But Juana was nothing if not intrepid and, no newcomer to politics, she shrugged off the personal attacks and succeeded Carles as Lieutenant General. She maintained an extensive court with separate chancery and treasurer, but without the judicial and legislative offices that Maria of Castile possessed in parallel with Alfonso’s Neapolitan court. Amid the turbulence and widespread civil unrest that erupted in the wake of Carles’s death, she suppressed opposition in the towns and countryside and secured support for her husband and Fernando. In June 1461, she negotiated on behalf of the Crown to moderate the anti-royalist Capitulations of Vilafranca del Penedés. Like her sister-in-law before her, Juana sided with the remenees, a position that made her highly unpopular with the city magistrates of Barcelona and the landlords. Unlike the six Aragonese queen-lieutenants who preceded her, Juana is noted for her active involvement in military actions, notably the early campaigns of the ten-year civil war. In June 1462, she and Fernando fled from forces led by the rebellious Count of Pallars and took refuge in a royal castle in Girona only to find themselves besieged for a month. She organized the defense of the castle and held the rebels at bay until Juan and Louis XI of France arrived with military support. Although not personally at the head of an army, she was a tough negotiator who rallied and helped organize and provision an array of forces in defense of the Crown in the Ampurdán, accompanied forces to Barcelona and into Aragón. She was a key negotiator in the treaties of Sauveterre and Bayonne in May 1462 that settled the succession of Navarre and allowed the French to occupy the territories of Rousillon and Cerdanya to France in return for military support. She was virtually prisoner, with her daughter Juana, in the castle of Lárraga in 1463. Hostilities worsened, the French, Castilians, and Portuguese intervened, and periodically the Catalans ‘deposed’ (most notably in 1462) Juan, Fernando (occasionally), and Juana. Her inclusion in this list, although a dubious honor, is a clear indication of her power and importance in the political sphere. After her release from Lárraga and as the civil war intensified, she turned her attentions to governing Crown realms as Lieutenant General from 1464 until her death in 1468. With Fernando at her side, and seeking to pacify the warring factions, she presided over the Cortes of Aragón that met in Zaragoza from 1466 to 1468. During this period, she traveled extensively throughout the realms in the midst of civil war, gathering troops and supplies, negotiating with military leaders while personally attending to the business of governing—collecting taxes, holding courts of justice, dealing with the church, managing Crown lands and her own patrimony. The war outlived her by four years, but it is fitting that her indefatigable work as co-ruler with her husband and as tutor to her son mark her as the last queen-lieutenant of the Crown of Aragon.

- Theresa Earenfight, Queenship and Political Power in Medieval and Early Modern Spain

#UNDERRATED RELATIONSHIP/PARTNERSHIP/FRIENDSHIP MEME#perioddramaedit#historyedit#women in history#men in history#juana enríquez#john ii of aragon#charlize theron#robert pugh

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leonor de Aragão, Queen of Portugal (Wife of King Duarte I of Portugal)

Tenure: 14 August 1433 – 9 September 1438

Coronation: 15 August 1433

Leonor of Aragon (2 May 1402 – 19 February 1445) was queen consort of Portugal as the spouse of Duarte I of Portugal and the regent of Portugal as the guardian of her son. She was the daughter of Fernando I of Aragon

and Leonor of Alburquerque.

On the paternal side, Leonor was the granddaughter of João I of Castile (the King who suffered a humiliated defeat by her future father in law, King João I of Portugal, in the Aljubarrota Battle)

and Leonor of Aragon:

through her mother, she was the granddaughter of Beatriz de Portugal,

and therefore the great-granddaughter of King Pedro I of Portugal

with Inês de Castro.

Therefore, she was a mixture of Portuguese, Castilian and Aragonese royal blood. He had six brothers, among them the Aragonese kings Afonso V

and João II.

Leonor's father died when she was 14 years old. Her mother eventually arranged her marriage to the future King Duarte of Portugal, which happened on 22 September 1428. They had nine children, of whom five survived to adulthood. None of them lived past age 50. In 1433, she became Queen of Portugal. As queen she was not active politically and quickly became unpopular.

When her husband died on 9 September 1438, she was appointed regent of Portugal in his will, which was confirmed by the Portuguese Cortes. However, she was inexperienced, in poor health and, as an Aragonese, unpopular with the people, who preferred the late king's brother Infante Pedro, Duke of Coimbra. The confirmation of her regency therefore caused a riot in Lisbon. The riot was suppressed by her brother Count João of Barcelona, later King João II of Aragon. Leonor was supported by the nobility and the will, while Pedro was supported by a fraction of the nobility and by the people. Negotiations for a compromise arrangement were drawn out over several months, but were complicated by the interference of the Count of Barcelos, who supported her, and the Archbishop of Lisbon, who supported Pedro. This period also witnessed the birth to her of a posthumous daughter, Joana in March 1439 and the death of her eldest daughter, Filipa from tuberculosis.

Eventually, the Cortes appointed Pedro the sole regent. Leonor continued conspiring, but fell seriously ill and was forced to go into exile in Castile in December 1440. She died at Toledo after a prolonged respiratory illness in February 1445 and is buried in Batalha, Portugal.

Leonor had nine children with King Duarte I:

Infante João (October 1429 - ?), Prince of Portugal.

Infanta Filipa (27 November 1430 - 24 March 1441), Died young.

Infante Afonso (15 January 1432 - 28 August 1481) Who succeeded him as Afonso V, King of Portugal.

Infanta Maria (7 December 1432 - 8 December 1432) Died in infancy.

Infante Fernando (17 November 1433 - 18 September 1470) Duke of Viseu. He was declared heir to his brother Afonso V for two brief periods, and therefore used the style of Prince instead of Infante. He was the father of future king Manuel I.

Infanta Leonor (18 September 1434 - 3 September 1467) Holy Roman Empress by marriage to Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor.

Infante Duarte (12 July 1435 - 12 July 1435) Died shortly after being born.

Infanta Catarina (26 November 1436 - 17 June 1463) She was betrothed to Charles IV of Navarre but he died before the marriage could take place. After his death, Catarina entered the Convent of Saint Claire and became a nun.

Infanta Joana (20 March 1439 - 13 June 1475) Queen of Castile by marriage to Henry IV of Castile.

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Castilian infantas aesthetic, part II

Leonor, queen of England and comtesse de Ponthieu. Daughter of Fernando III and Jehanne de Dammartin, comtesse de Ponthieu. Mother of Eleanor of Windsor, comtesse de Bar; Joan of Acre, Countess of Hertford; Margaret of Windsor, Hertogin van Brabant; Mary of Woodstock; and Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, Countess of Hereford.

Beatriz, marchesa del Monferrato. Daughter of Alfonso X and Violant d’Aragó. Mother of Violante degli Aleramici di Monferrato, Byzantine Empress.

Violante, señora de Vizcaya. Daughter of Alfonso X and Violant d’Aragó. Mother of María Díaz de Haro, señora de Tordehumos.

Beatriz, rainha de Portugal. Daughter of Sancho IV and María de Molina. Mother of Maria de Portugal, reina de Castilla and Leonor de Portugal, reina d’Aragó.

Leonor, reina d’Aragó. Daughter of Fernando IV and Constança de Portugal.

Constanza, Duchess of Lancaster. Daughter of Pedro I and María de Padilla. Mother of Catherine of Lancaster, reina de Castilla.

Isabel, Duchess of York. Daughter of Pedro I and María de Padilla. Mother of Constance of York, Countess of Gloucester.

Leonor, reine de Navarre and comtesse d’Évreux. Daughter of Enrique II and Juana Manuel. Mother of Joana Nafarroakoa, comtessa de Fois; Zuria I.a Nafarroakoa; Elisabet Nafarroakoa, comtessa d’Armanhac; and Beatriz Nafarroakoa, comtesse de La Marche. Grandmother of Zuria II.a Nafarroakoa and Leonor I.a Nafarroakoa.

María, reina d’Arago and regina de Sicilia. Daughter of Enrique III and Catherine of Lancaster.

#house of ivrea#medieval#house of trastamara#historyedit#spanish history#european history#women's history#nanshe's graphics#royalty aesthetic

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

Juana of Portugal (1439-1475)

She was the posthumous daughter of King Duarte of Portugal and his wife Leonor of Aragon. Juana grew up in exile with her mother, due to the intrigues of the Portuguese court, and lived first at the Monastery of Santa María in Medina del Campo and later in Toledo, where Leonor of Aragon died. At the age of six, Juana returned to the Portuguese court of her brother Afonso V.

In 1455 the young Juana married her cousin Enrique IV of Castile, who had repudiated his first consort after thirteen years of marriage. The couple produced no children. The marriage was annulled on the grounds of an impotence that was specific rather than general, an impotence that applied only to Enrique’s relationship with Blanca of Navarre. Yet such an extraordinary explanation amounted to a case of maleficium (spell), with the clear implication that Blanca was the guilty party, and in addition she was obliged to leave Castile and return to Navarre.

Juana of Portugal was described as beautiful, cheerful and coquettish. The sources speak of the licentiousness introduced by the young Queen and her ladies in the austere Castilian court. They liked to use perfums, makeups, dresses that displayed too much décolletage, and flirting with men. One of her ladies, Guiomar de Castro, was King’s mistress, causing the anger of the Queen, and other, Mencía de Lemos, was Cardinal Mendoza’s mistress.

Six years after her wedding, Queen Juana was pregnant. Some say it was a miracle, others that it was the result of some sort of artificial insemination that the couple had tried, as was recorded by a german traveler. During this period, Juana insisted that Enrique's teenaged brother and sister, Alfonso and Isabel, forcefully be brought to the court and away from their sick mother. Many saw this as a way of making sure her daughter's path to the crown would encounter no obstacles. The Queen gave birth to a daughter named Juana, officially proclaimed heir to the Crown of Castile and created Princess of Asturias.

Queen Juana planned the marriage between her sister-in-law, Isabel of Castile, and her brother Afonso V of Portugal, and her daughter with her nephew Prince Joao. She wanted with these weddings an annexation of the Crown of Castile with the kingdom of Portugal.

In early 1460s, Castilian nobles became dissatisfied with the rule of Enrique IV, and believed that Princess Juana was not King’s daughter. They called her la Beltraneja, a mocking reference to her supposed illegitimacy. Propaganda and rumour encouraged by the league of rebellious nobles argued that her father was Beltrán de la Cueva, a royal favorite of low background who had been elevated to enormous power by Enrique and who, by some, has been suggested as Enrique's lover.

Many nobles refused to recognise Princess Juana and preferred that Enrique instead name his younger half-brother, Alfonso as his heir. This was agreed to on the condition that Alfonso marries little Juana. Not long after this, Enrique reneged on his promise and began to support his daughter's claim once more. The nobles in league against him conducted a ceremonial deposition-in-effigy of Enrique outside the city of Avila and crowned Alfonso as a rival king.

Queen Juana and her daughter were removed from the court. They lived in various castles as hostages, separately or together, protected by a faction of the nobility. The love affair of Queen Juana with the Bishop Fonseca’s nephew, Pedro of Castile, and the birth of her two illegitimate sons, caused great scandal. As a result of the need to conceal the pregnancy of her illegitimate sons, Juana of Portugal is considered the inventor of the farthingale.

In 1468, Alfonso of Castile died and Princess Juana was stripped of her succession-rights. Her aunt, Infanta Isabel, was placed before her, on condition that Isabel marry a man chosen out by the monarch. Queen Juana and her daughter sent a formal appeal to the Supreme Pontiff. Enrique accepted to divorce his wife and send her to Portugal, but Juana remained in Castile as king's wife, though separated of her husband. Isabel married Fernando of Aragon with the opposition of Enrique IV.

In 1470, Princess Juana was engaged and then married by proxy to the Duke of Guienne, brother of Louis XI of France. In the face of the French ambassador, King Enrique and Queen Juana swore before a crucifix that the Princess was their legitimate daughter. The French marriage never consummated, because the duke died two years later in France. Queen Juana always defended her daughter’s rights to the throne, and she had an active political participation. Queen Juana tried to get the support of nobles and cities, but with meager success and without palpable results. In 1474, Enrique IV died at the Alcázar of Madrid and rumors circulated that the late monarch had been poisoned, his wife and his daughter demanded an investigation. Queen Juana died a few months after her husband’s death at the age of 36. In the last months of her life, she lived at the convent of San Francisco in Madrid. The cause of her death is unknown.

Bárbara Lennie played Juana of Portugal in TV series "Isabel"

#juana de portugal#juana de avis#joan of portugal#women in history#spanish history#barbara lennie#Isabel tve#enrique IV#juana la beltranejs#juana de trastamara#juana de castilla

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bastard Kings and their families

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

1) Ferdinand I of Naples ( 1424 – 1494), son of Alfonso V of Aragon and Giraldona Carlino

2) Alfonso V of Aragon (1396 – 1458), son of Ferdinand I of Aragon and his wife Leonor de Albuquerque

3) Isabella of Taranto or Clermont (c. 1424 – 1465), daughter of Tristan of Clermont and Catherine of Taranto

4) Alfonso II of Naples ( 1448 – 1495), son of Ferdinand I of Naples and his wife Isabella of Taranto

5) Eleanor of Naples (1450 – 1493) & Beatrice of Naples (1457 – 1508), daughters of Ferdinand I of Naples and his wife Isabella of Taranto

6) Frederick I of Naples (1452 – 1504), son of Ferdinand I of Naples and his wife Isabella of Taranto

7) Ferdinand of Aragon and Guardato (before 1494–1542), son of Ferdinand I of Naples and Diana Guardato

8) Eleanor of Aragon (1402 – 1445), daughter of Ferdinand I of Aragon and Leonor de Albuquerque

9) I. John II of Aragon & Navarre (1398- 1479), son of Ferdinand I of Aragon and his wife Leonor de Albuquerque

II. Blanche I of Navarre (1385-1441), daughter of Charles III of Navarre and his wife Eleanor of Castile

III. Blanche II of Navarre (1424 – 1464), daughter of John II of Aragon and his wife Blanche I of Navarre

IV. Eleanor I of Navarre (1426 - 1479), daughter of John II of Aragon and his wife Blanche I of Navarre

V. Charles of Viana/ Charles IV of Navarre (1421- 1461), son of John II of Aragon and his wife Blanche I of Navarre

VI. Ferdinand II of Aragon & V of Castile (1452-1516), son of John II of Aragon and his wife Juana Enríquez

10)

I. Mary of Aragon ( 1403- 1445), daughter of Ferdinand I of Aragon and his wife Leonor de Albuquerque

II. John II of Castile (1405- 1454), son of Henry III of Castile and his wife Catherine of Lancaster

III. Henry IV of Castile (1425-1474), son of John II of Castile and his wife Mary of Aragon

IV. Isabella of Portugal (1428 - 1496), daughter of John of Portugal and Isabella of Barcelos

V. Isabella I of Castile (1451-1504), daughter of John II of Castile and his wife Isabella of Portugal

VI. Alfonso of Castile (1453-1468), son of John II of Castile and his wife Isabella of Portugal

#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#canonjonsnow#day 10#echoes of the past#historical parallels#medieval bastard kings#bastard kings and their families#ferdinand i of naples#alfonso v of aragon#isabella of taranto#alfonso ii of naples#eleanor of naples#beatrice of naples#frederick i of naples#ferdinand of aragon and guardato#eleanor of aragon#john ii of aragon#blanche i of navarre#blanche ii of navarre#eleanor i of navarre#charles of viana#ferdinand ii of aragon#mary of aragon#john ii of castile#henry iv of castile#isabella of portugal#isabella i of castile#alfonso of castile

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

In order to prevent Blanca (II of Navarre) from opposing the terms of the treaty and her disinheritance, it was decided to send her north on the pretext of marrying Charles, Duke of Berri and brother of Magdalena and Louis XI. When Blanca rejected the idea of the match and refused to leave Navarre, she was taken by force. By April 23, she had reached the monastery of Roncesvalles, where she wrote a lengthy missive, protesting about her abduction, claiming “my father took me by force and contrary to my will.” In this document, Blanca repeatedly refers to herself as “the firstborn [eldest] and queen regnant and Lady and heiress of the said kingdom,” which she noted came to her through “the maternal line.” The princess castigated her father for his treatment of the Principe de Viana, claiming Juan had “forgotten the love and paternal duty” that he owed his eldest son. Blanca also blamed her sister and brother-in-law’s ambition to rule Navarre for her plight; “The said Count of Foix and his wife, my sister, are taking me to exile me and to disinherit me of my kingdom of Navarre.”

Blanca became increasingly desperate as she was taken further north, drafting appeals for help to her former husband, the King of Castile, her cousin the Count of Armagnac and the head of her Beaumont supporters. By April 30, she gave up her brave defense of her position as the rightful queen and attempted to donate her right to the crown to her ex-husband, Enrique of Castile, rather than see the kingdom go to her younger sister. Once Blanca reached the northern frontier of Navarre, she was transferred to the custody of the Captal de Buch and imprisoned in the castle of Orthez, a stronghold that belonged to her brother-in-law, Gaston of Foix.

Blanca’s removal did not quiet her supporters or end the struggle over the succession of the realm. Civil war still raged between the Beaumonts, who championed Blanca, and their rivals, the Agramonts, and matters had been made worse by Enrique of Castile’s decision to invade Navarre to press the claim to the throne that his ex-wife had bestowed on him. The Bishop of Pamplona attempted to resolve the situation with the Accord of Tafalla in late November 1464, which called for Blanca’s return to Navarre in order to settle the matter of the succession. Unfortunately, Blanca was unable to respond to the summons as she died, rather suspiciously, shortly afterward on December 2, 1464. Her sister Leonor has been repeatedly accused by chroniclers, historians, novelists, and other writers of being involved in Blanca’s death, although there is little definitive evidence to support this allegation. There is no doubt that Leonor had a motive for her sister’s murder, but Courteault has argued that given that only ten days lapsed between the ratification of the agreement and the death of the princess, it is difficult to claim that Blanca was killed specifically in response to the drafting of the accord. The eighteenth-century historian Enrique Flórez accurately summed up Blanca’s difficult position: “because [she] did not have the strength to maintain the right to the crown, she lost not only the kingdom, but her freedom and her life.

-Elena Woodacre, "The Queens Regnant of Navarre: Succession, Politics and Partnership, 1274-1512"

#💔#Juan the Faithless is one of the worst historical fathers I have ever read about#he was beyond awful#he destroyed his son's life as well#Juana of Castile was his granddaughter and was treated just as badly by HER father (Juan the Faithless's son Ferdinand II of Aragon)#i guess this is where he learnt it from#historicwomendaily#blanca ii of navarre#blanche ii of navarre#15th century#my post

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

11th King of Portugal (2nd of the Aviz Dynasty): King Duarte I of Portugal, “The Philosopher/The Eloquent”

Reign: 14 August 1433 – 9 September 1438

Predecessor: João I

Duarte (31 October 1391 in Viseu – 9 September 1438 in Tomar), known in English as Edward and called the Philosopher (o Rei-Filósofo) or the Eloquent (o Eloquente), was King of Portugal from 1433 until his death. He was born in Viseu, the son of João I of Portugal and his wife, Philippa of Lancaster. Duarte was the oldest member of the "Illustrious Generation" of accomplished royal children who contributed to the development of Portuguese civilization during the 15th century. As a cousin of several English kings, he became a Knight of the Garter, like a father before him.

Before he ascended the throne, Duarte always followed his father in the affairs of the kingdom. He was knighted in 1415 after the Portuguese capture of the city of Ceuta in North Africa, across from Gibraltar, in the Battle of Ceuta. He became king in 1433, when his father death.

As king, Duarte soon showed interest in building internal political consensus. During his short reign of five years, he called the Portuguese Cortes (the national assembly) no less than five times to discuss the political affairs of his kingdom. He also followed the politics of his father concerning the maritime exploration of Africa. He encouraged and financed his famous brother, Henrique the Navigator, who initiated many expeditions on the west coast of Africa. An expedition of Gil Eanes

in 1434 first rounded Cape Bojador

on the northwestern coast of Africa, leading the way for further exploration southward along the African coast.

The colony at Ceuta rapidly became a drain on the Portuguese treasury, and it was realized that without the city of Tangier, possession of Ceuta was worthless. After Ceuta was captured by the Portuguese, the camel caravans that were part of the overland trade routes began to use Tangier as their new destination. This deprived Ceuta of the materials and goods that made it an attractive market and a vibrant trading locale, and it became an isolated community.

In 1437, Duarte's brothers Henrique and Fernando persuaded him to launch an attack on the Marinid sultanate of Morocco. The expedition was not unanimously supported and was undertaken against the advice of the Pope. Infante Pedro, Duke of Coimbra, and the Infante João were both against the initiative; they preferred to avoid conflict with the Marinid Sultan. Their instincts proved to be justified. The resulting Battle of Tangier, led by Henrique, was a debacle. Failing to take the city in a series of assaults, the Portuguese siege camp was soon itself surrounded and starved into submission by a Moroccan relief army. In the resulting treaty, Henrique promised to deliver Ceuta back to the Marinids in return for allowing the Portuguese army to depart unmolested. Duarte's youngest brother, Fernando, was handed over to the Marinids as a hostage for the final handover of the city.

The debacle at Tangier dominated Duarte's final year. Pedro and João urged him to fulfill the treaty, yield Ceuta and secure Fernando's release, whereas Henrique (who had signed the treaty) urged him to renege on it. Caught in indecision, Duarte assembled the Portuguese Cortes at Leiria in early 1438 for consultation. The Cortes refused to ratify the treaty, preferring to hang on to Ceuta and requesting that Duarte find some other means of obtaining Fernando's release.

Duarte died late that summer, in Tomar, of the plague, like his mother. Popular lore suggested he died of heartbreak over the fate of his hapless brother; Fernando would remain in captivity in Fez until his own death in 1443.

Her son Afonso was only 6 years old when Duarte died in 1438. In the testament the king handed over the regency to the queen, Leonor, his wife. This measure was not to the liking of the population. There was a disagreement in the family to decide who would be conductor.

He lies in the Imperfect Chapels

of the Monastery of Santa Maria da Vitória, in Batalha,

next to Queen Leonor.

Duarte married Leonor of Aragon, a daughter of Fernando I of Aragon and Leonor of Albuquerque, in 1428. They had 9 children:

Infante João (October 1429 - ?), Prince of Portugal.

Infanta Filipa (27 November 1430 - 24 March 1441), Died young.

Infante Afonso (15 January 1432 - 28 August 1481) Who succeeded him as Afonso V, King of Portugal.

Infanta Maria (7 December 1432 - 8 December 1432) Died in infancy.

Infante Fernando (17 November 1433 - 18 September 1470) Duke of Viseu. He was declared heir to his brother Afonso V for two brief periods, and therefore used the style of Prince instead of Infante. He was the father of future king Manuel I.

Infanta Leonor (18 September 1434 - 3 September 1467) Holy Roman Empress by marriage to Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor.

Infante Duarte (12 July 1435 - 12 July 1435) Died shortly after being born.

Infanta Catarina (26 November 1436 - 17 June 1463) She was betrothed to Charles IV of Navarre but he died before the marriage could take place. After his death, Catarina entered the Convent of Saint Claire and became a nun.

Infanta Joana (20 March 1439 - 13 June 1475) Queen of Castile by marriage to Henry IV of Castile.

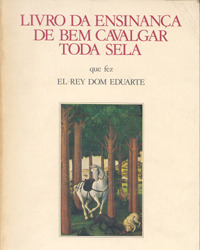

Another less political side of Duarte's personality is related to culture. A reflective and scholarly infante, he wrote the treatises O Leal Conselheiro (The Loyal Counsellor)

and Livro Da Ensinança De Bem Cavalgar Toda Sela ("Book of Teachings on Riding Well on Every Saddle")

as well as several poems. He was in the process of revising the Portuguese law code when he died.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen Philippa and King João I children.

1º: King Duarte

11th Monarch of Portugal. Born in Viseu, October 31, 1391, and died in Tomar, September 9, 1438.

He was crowned king in Leiria, in 1433.

Despite his reign being short, he decreed the Mental Law (a ‘Lei Mental’) – a measure towards centralisation in order to defend the spoils of the crown.

He became involved in government while his father was still alive. In 1412, King João I officialised his association with the governance and included him in its administration.

He was a cultured man with love of letters, owning a library filled with classical authors and thinkers of the Church, as his book The Loyal Counsellor shows.

He also wrote The Art of Riding on Every Saddle.

His reign was marked by the Tangier campaign of October 1437, which resulted in failure and a great defeat for the Portuguese forces.

The consequence of this defeat was having to leave the Infante Fernando as a hostage while Henrique came to Lisbon to present the Moroccans’ terms for a treaty: Portugal handing back Ceuta in exchange for the life of the Infante. As this exchange never took place, the latter earned the name of the Saint Prince, after he died in captivity.

Duarte married Leonor (Eleanor) of Aragon in Coimbra on September 22, 1428 and they had 9 children:

Infante João: Born in October 1429/ Died in August 14th 1433: Prince of Portugal, died young.

Infanta Filipa: Born in November 27th 1430/ Died in March 24th 1439: Died young

Infante Afonso: Born in January 15th 1432/ Died in August 28th 1481: Who succeeded him as Afonso V, King of Portugal;

Infanta Maria: Born in December 7th 1432/ Died in December 8th 1432: Died in infancy;

Infante Fernando: Born in November 17th 1433/ Died in September 18th 1470: Duke of Viseu. He was declared heir to his brother Afonso V for two brief periods, and therefore used the style of Prince instead of Infante. He was the father of future King Manuel I.

Infanta Leonor: Born in September 18th 1434/ Died in September 3rd 1467: Holy Roman Empress by marriage to Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor;

Infante Duarte: Born in July 12th 1435/ Died in July 12th 1435: Died shortly after being born;

Infanta Catarina: Born in November 26th 1436/ Died in June 16th 1463: She was betrothed to Charles IV of Navarre but he died before the marriage could take place. After his death, Catherine entered the Convent of Saint Claire and became a nun;

Infanta Joana: Born in March 20th 1439/ Died in June 13th 1475: Queen of Castile by marriage to Henry IV of Castile.

He decided to build his own Pantheon at the Monastery of Batalha and it is there that his mortal remains are laid to rest, beside those of his wife. The space is known today as the Unfinished Chapels, being an arrangement of seven chapels destined for King Duarte and his lineage, which, however, were never finished.

He earned the name of The Eloquent, due to his writings, and the motto Léauté Faray Tã ya Serey was also his.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

9th King of Portugal and Last King of the Burgundy Dynasty: King Fernando of Portugal, “The Handsome”

Reign: 18 January 1367 – 22 October 1383

Predecessor: Pedro I

Fernando I (31 October 1345 in Coimbra – 22 October 1383 in Lisboa), sometimes called the Handsome (o Formoso) or occasionally the Inconstant (o Inconstante), was the King of Portugal from 1367 until his death in 1383. His death led to the 1383–85 crisis, also known as the Portuguese interregnum.

Fernando was born in Coimbra, the second but eldest surviving son of Pedro I and his wife, Constança Manuel. On the death of Pedro of Castile in 1369, Fernando, as great-grandson of Sancho IV by his grandmother Beatriz, laid claim to the vacant Castilian throne. The kings of Aragon and Navarre, and later John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, who had married Pedro of Castile's eldest daughter, Constança, also claimed the throne.

The throne was held by his second cousin Henry of Trastámara (Henry II of Castile), Pedro of Castile's illegitimate brother, who had defeated him in the Castilian Civil War in 1366 and assumed the crown. After one or two indecisive campaigns, all parties were ready to accept the mediation of Pope Gregory XI. The conditions of the treaty, ratified in 1371, included a marriage between Fernando and Leonor of Castile. But before the union could take place Ferdinand had become passionately attached to Leonor Telles de Meneses, the wife of one of his own courtiers. Having procured a dissolution of her previous marriage, he lost no time in making Leonor his queen.

This conduct, although it raised a serious insurrection in Portugal, did not at once result in a war with Henry. However, the outward concord was soon disturbed by intrigues with John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster,

brother of Edward the Black Prince, who entered into a secret treaty with Fernando for the expulsion of Henry from his throne. The war which followed was unsuccessful; and peace was again made in 1373.

On the death of Henry in 1379, the Duke of Lancaster once more put forward his claims, and again found an ally in Portugal. According to the Continental annalists, the English proved as offensive to their allies as to their enemies in the field. So Fernando made a peace for himself at Badajoz in 1382. It stipulated that Beatriz, Fernando's daughter and heiress, would marry King João I of Castile, and thus secure the ultimate union of the two crowns.

Fernando left no male heir when he died at Lisbon on 22 October 1383, and the direct Burgundian line, which had been in possession of the throne since the days of Count Henry (about 1112), became extinct. The stipulations of the treaty of Badajoz were set aside, and João, Grand Master of the order of Aviz, Fernando's illegitimate brother, claimed the throne. This led to a period of war and political indefinition known as the 1383-1385 Crisis. João became the first king of the House of Aviz in 1385.

The remains of D. Fernando were deposited in the Convent of São Francisco, in Santarém, as left in the will by the monarch. In the 19th century, the tomb was the target of serious acts of vandalism and degradation, first as a result of the French Invasions, when a significant portion of the walls of the sarcophagus were broken when it became difficult to remove the cover and the extinction of religious orders in 1834, when the convent was abandoned. What is certain is that the king's remains were lost forever, with no record of this desecration reaching today.

Today D. Fernando spectacular ornate tomb can be found on display at the Carmo Archaeological Museum in Lisbon.

Fernando married Leonor Teles de Meneses, formerly the wife of the nobleman João Lourenço da Cunha, Lord of Pombeiro, and daughter of Martim Afonso Telo de Meneses.

By Leonor Teles (1350- 27 April 1386; married in 1372)

Infanta Beatriz (1373 - 1420) Heiress of her father. Married King João I of Castile, legitimate son of Henry II of Castile.

Infante Afonso (1382 - 1382) lived 4 days.

Infanta Isabel (1383 - 1383) lived a few hours.

Illegitimate offspring

Isabel of Portugal (1364 - 1395) Countess of Gijón and Noreña through marriage to Afonso Enríquez, illegitimate son of Henry II of Castile.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Aragonese infantas aesthetic, part II

Maria, señora de Cameros. Daughter of Jaume II and Blanche d’Anjou. Mother of Blanca de Castilla.

Elisabet, Königin des Heiligen Römischen Reichs. Daughter of Jaume II and Blanche d’Anjou. Mother of Anna von Habsburg, Herzogin von Bayern.

Constança, reina de Mallorca. Daughter of Alfons IV and Teresa d’Entença. Mother of Elisabet de Mallorca, marchesa di Monferrato.

Constança, regina di Sicilia. Daughter of Pere IV and Marie de Navarre. Mother of Maria, regina de Sicilia.

Elionor, reina de Castilla. Daughter of Pere IV and Elionor de Sicília. Grandmother of María de Castilla, reina d’Aragó; Catalina de Castilla, duquesa de Villena; Maria d’Aragó, reina de Castilla; and Elionor d’Aragó, rainha de Portugal.

Elisabet, comtessa d’Urgell. Daughter of Pere IV and Sibilla de Fortià. Mother of Elisabet d’Urgell, duquesa de Coimbra.

Joana, comtessa de Fois. Daughter of Joan I and Marta d’Armanhac.

Violant, duchesse d’Anjou and regina di Napoli. Daughter of Joan I and Yolande de Bar. Mother of Marie d’Anjou, reine de France. Grandmother of Isabelle d’Anjou, duchesse de Lorraine; Marguerite d’Anjou, Queen of England; Radegonde de France; Catherine de France, comtesse de Charolais; Yolande de France, duchessa di Savoia; Jehanne de France, duchesse de Bourbon; and Madeleine de France, Vianako printzesa.

Maria, reina de Castilla. Daughter of Ferran I and Leonor Urraca de Castilla, condesa de Alburquerque. Grandmother of Juana la Beltraneja de Castilla.

Elionor, rainha de Portugal. Daughter of Ferran I and Leonor Urraca de Castilla, condesa de Alburquerque. Mother of Leonor de Portugal, Sacri Romani Imperatrix; Catarina de Portugal; and Joana de Portugal, reina de Castilla. Grandmother of Santa Joana de Portugal; Leonor de Viseu, rainha de Portugal; Isabel de Viseu, duquesa de Bragança; Kunigunde von Österreich, Herzogin von Bayern-München; and Juana la Beltraneja.

#house of barcelona#medieval#house of trastamara#historyedit#spanish history#european history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics#royalty aesthetic

120 notes

·

View notes