#Sulawesi Palm Civet

Text

okokok i wanna make a list of interesting animals that i like and some of which i have trouble remembering sometimes. i will edit this over time. ok. i thought we would be able to do readmores on mobile by now but apparently not. ok (i also always forget the word reconcile so that can be here too)

...

MARSUPIALS common brushtail possum, quoll, tasmanian devil, thylacine, cuscus (common spotted cuscus, sulawesi bear cuscus, silky cuscus), opossum (white-eared opossum, four-eyed opossum, yapok/water opossum), tree kangaroo, glider (greater glider, yellow-bellied glider)

RODENTS rat, mouse, nutria, Gambian pouched rat, capybara, Brazilian porcupine, jerboa (long-eared jerboa), chinchilla, vizcacha

MUSTELIDS ferret, weasel, stoat, marten (yellow-throated marten), skunk (spotted skunk), mink, greater hog badger

PRIMATES tarsier, aye aye, ring tailed lemur, japanese macaque, gelada, marmoset (pygmy marmoset), capuchin, spider monkey (red-faced spider monkey), howler monkey, white-faced saki

VIVERRIDS binturong, civet (owston's palm civet, African civet, banded palm civet), linsang, genet

PROCYONIDS kinkajou, coati, ringtail/cacomistle, raccoon

HOGS wild boar (really been enjoying these lately) , red river hog, pygmy hog

FELINES margay, rusty-spotted cat, black-footed cat, asiatic golden cat, bornean bay cat, little spotted cat/oncilla, jaguarundi, sandcat, lynx, bobcat, caracal, serval, fishing cat, pallas' cat

ANTEATERS tamandua, giant anteater, silky anteater, pangolin

LAPINES rabbit (flemish giant rabbit, sumatran striped rabbit, Netherland dwarf broken chocolate colour (someone said i would be this if i was a bunny)), hare

OTHER MAMMALS fossa, mongoose (yellow mongoose, common slender mongoose), elephant shrew (black and rufous elephant shrew), treeshrew, colugo, spotted hyena, antelope (oryx, roan antelope), honduran white bat

FISH eel (New Zealand longfin eel, moray eel, gulper eel), black ghost knife fish

ARACHNIDS jumping spider, house spider, daddy long legs, huntsman spider, tarantula, camel spider, tailless whip scorpion, horseshoe crab

OTHER INVERTEBRATES snail (giant African snail), slug, slater/pill bug, isopod, praying mantis, bee (honeybee, bumble bee), moth, millipede, centipede, earwig, beetle, sand hopper

...

ok now im tired and im going to go to bed. i will readmore this tomorrow when im on the computer maybe. goodnight

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Macrogalidia musschenbroekii - Sulawesi Palm Civet

#sulawesi palm civet#sulawesi civet#civet#macrogalidia#musschenbroekii#viverridae#carnivora#mammalia#chordata#animalia#vulnerable#asia#southeast asia#indonesia#terrestrial#forest#mountain#needs research#thefaunalfrontier#the faunal frontier

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Civets as well a Genets are very fascinating, adorable creatures. Genets actually make good pets. These animals are feline-like in appearance, either carnivorous or omnivorous, but are not related to actual felines. They are nocturnal and rest in tress, rock crevices, and empty burrows. Civets and Genets are usually solitary.

“The vocal African palm civet spends most of it’s time the forest canopy, where it feeds chiefly on the fruits of trees and vines and occasionally on small animals and birds. All other species of pine civets are confined to the forests of Asia. They are skillful climbers, aided by their sharp, curved, retractable claws, usually naked soles, and partly fused third and fourth toe, which strengthen the grasp of the hindfeet” (Mcdonald pg. 124).

The fossa is a species of Civet that is found only in Madagascar. They have long tails which help with climbing as well as keeping their balance when hunting in the treetops. They look a lot like a big cat. They take up the niches that lions, tigers, or other feline apex predators would because there are no feline species native to the island. They are much closer related to mongooses than actual felines. Even so, they have retractable claws, akin to those of a feline. They can potentially grow up to six feet long and weigh 26 pounds.

Sulawesis or Great or Brown palm civets have webbed, flexible feet. In Southeast Asian forests, there are five species of banded palm civets and otter civets. Banded palm civets eat lizards, frogs, rats, crabs, snails, earthworms, and ants. Owson’s banded civet mainly eats invertebrates. Hose’s palm resembles the banded palm civet in body but has a differing head shape. Otter civets have shorter rounded ears, a thinner pointier muzzle, a more compact body, and a shorter tail. African civets live in all habitats on the continent. Indian civets are smaller than Indian civets and eat small mammals and birds, stalking prey like a cat. They also scavenge and eat eggs.

Binturongs or bearcats have been reported to swim in rivers and catch fish. They resemble a combination of bears and cats but are not ursine or feline. Their long, fluffy tails sometimes serve as a fifth hand. They can potentially live up to 20 years. They are found in forests throughout Southeast Asia. Unfortunately, they are a vulnerable species due to habitat destruction.

Binturongs are thought to be the most closely related to palm civets. They are generally solitary and nocturnal, like most civets. They are generally shy animals, and hard to spot, especially due to their endangered status. The habitat loss has been worse in the southern range of territory. They rely on thick, dense forests for shelter and safety.

#Civets#Mammal Encylopedia#Genets#David Macdonald#African Pine Civet#Madagascar#Fossa#Southeast Asia#Binturong#Bearcat#Sulawesi#Great Palm Civet#Brown Palm Civet#Banded palm civet#Owson's banded civet#Hose's palm civet#Otter civets#African civets#Indian Civets

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

0 notes

Text

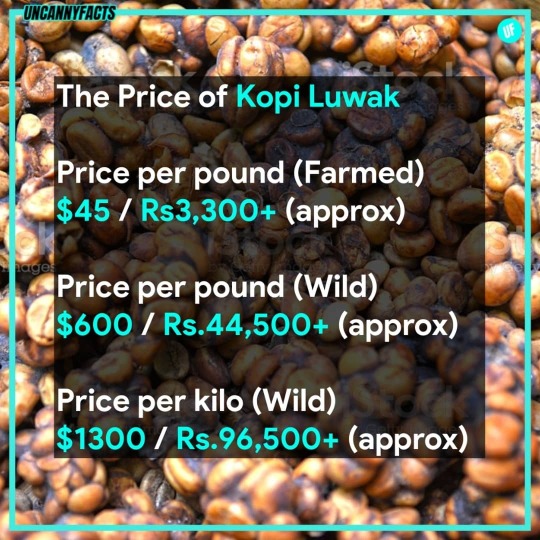

✨Kopi luwak or Civet coffee is a coffee that consists of partially digested coffee cherries, which have been eaten and defecated by the Asian palm civet.

The cherries are fermented as they pass through a civet's intestines, and after being defecated with other fecal matter, they are collected. This Coffee is produced mainly on the Indonesian islands of Sumatra, Java, Bali, Sulawesi, and in East Timor.

Civet coffee has been called one of the Most Expensive coffees in the world, with retail prices reaching US$100 per kilogram for farmed beans and US$1,300 per kilogram for wild-collected beans!

✨Follow @uncannyfacts for more such Weird & Amazing stuff!

#uncannyfacts#uncannymedia#uncannyrajan#facts#education#factsoftheday#coffee#coffeetime#mochacoffee#cappuccino#espresso#frappuccino

0 notes

Text

Kopi Luwak (Kape Alamid): The World’s Most Expensive Coffee From Asia

Would you dare try to have a cup of the world’s most expensive coffee from Asia? Why wouldn’t you? The more expensive it is, the better, right? Called kopi luwak (Indonesian word for civet cat), this type of coffee is mainly produced in the forests of Indonesia. The islands of Sulawesi, Bali, Sumatra and Java are particularly known for producing kopi luwak. Another major producer of kopi luwak is the Philippines, located just north of the Sulawesi sea. Locally called kape alamid, kopi luwak is produced in various regions of the country, mainly through farming.

The demand of kopi luwak is steadily increasing. Through social media and the internet, it is not surprising. This is true especially in Europe, where the top consumers of coffee are located, according to Statistica. From a region of high-income earners, Europeans would not mind spending top dollar for a cup. According to Most Expensive Coffee, a cup of kopi luwak can go as high as $100. That’s around Rp 1,454,200 (Indonesian rupiah) or ₱ 4,800 (Philippine peso).

To satisfy the rising demand for this luxury coffee, more producers have to answer the call. Apart from Indonesia and the Philippines, Asian countries, Cambodia, China, and Vietnam now produce kopi luwak. India, one of the largest producers of coffee ventured into the kopi luwak business in 2017.

You may be wondering. What makes it so expensive?

Kopi luwak and Asian palm civet cat

A palm civet cat

Growing this coffee isn’t the same thing as your regular coffee. With coffee luwak, there is one special creature required to make this coffee—the Asian palm civet cat.

The Asian palm civet cat is a cat-like animal native to South East Asia. It is not really like those domestic cats. Its close relatives include the mongoose. The Asian palm civet cat is a noctural animal— very active during the night and has a plant-based diet. It is particularly fond of consuming coffee cherries. But it is picky when it comes to it. It makes sure the coffee cherry it eats is ripe, fleshy, and flavorful. When digested, these coffee cherries undergo a special fermentation process. The pulp is removed. But the coffee beans are not digestible, and instead are defecated after 24 hours. This process is responsible for the complex, yet unique flavor profile of kopi luwak. The coffee is interestingly low in caffeine and less bitter.

Sounds disgusting to bear the name of being the world’s most expensive coffee from Asia? It is not really, and is perfectly safe to consume. The farmers collect these beans and further processed them. Washed, dried, pounded, and roasted to become the final product—kopi luwak coffee beans.

The limited supply is keeping it to cost an arm and a leg

A civet palm enjoying a tree of coffee cherries in the Philippines, via AgriBusiness Philippines

This unique way of production is just one of the reasons for its high price tag. Another is its rarity. We’ve mentioned several Asian countries that produce kopi Luwak. But at a production rate of 50 tons of coffee luwak annually, it is still a long way ahead.

At first, kopi luwak production was done naturally. Civet cats roam freely in the forests of Indonesia. And workers forage the forest for feces of civet cats. But relying with this method would not be able to keep up with the increasing demand. One immediate solution is the establishment of civet farms. In the Philippines, kape alamid is produced by farming on a large scale.

You might also like: How Does Tempering Chocolate Exactly Work?

But kopi luwak produced by caged civet cats usually produce lower quality coffee beans. This is mainly due to the fact that they are no longer able to select quality coffee cherries to eat, as they do in the wild. Because of this, there is a significant gap in the prices between farmed and wild kopi luwak. According to Eleven Coffees, a cup of farmed kopi luwak can go as little as $4 in producing countries like Indonesia. While the cheapest cup of wild kopi luwak is priced at $35. See the wide margin in the prices?

And like expected, these prices go higher outside the country of origin. If you are from places like Indonesia or the Philippines, try to search for kopi luwak at your local supermarket. The price will dictate its quality.

Watch out for fake kopi luwak

Kopi luwak beans from feces of Asian palm civet cat, via Wibowo Djatmiko

Kopi luwak is another victim food fraud, to no surprise. As you can imagine, wild kopi luwak—ones eaten, digested, and excreted by free-roaming Asian palm civet cat in the forest—is the highly valued here. Many sellers of this luxury coffee have started to have their presence online. And some have ridiculous prices, to say the least. You could find “wild” kopi luwak with prices as high as $2800 per kilo. The question is, are they legitimate kopi luwak?

Like most expensive items, there are more fake kopi luwak than real ones. In fact, around 70% of kopi luwak sold at coffee shops and those on online stores are not real. You can see it for yourself. Try to search for kopi luwak on ecommerce websites. Head to the customer reviews section. I hope you do not read words like, “just like a regular cup of coffee”, or “not real”. And since you are there, why don’t you check the stock. Is it available?

The most common fraudulent act with this coffee is labeling farmed as wild kopi luwak to increase the price. Sure, labels say “100% wild – civets are never caged or force-fed”, or “Collected by hand from wild Asian palm civets”. But how certain it is genuine?

Identifying genuine kopi luwak

Raw Indonesian kopi luwak

There is not much work or study done on this exquisite Asian coffee. In order to determine if the coffee is real kopi luwak, one website suggests to check out pictures of the farm or the processed coffee beans. But what are the odds you are receiving fake photos?

In 2013, a group of Indonesian and Japanese biotechnologists led by Sastia Prama Putri of the Department of Biotechnology of Osaka University in Japan developed the first chemical test that authenticates Asian palm civet cat coffee.

They ground 21 coffee varieties, including 7 varieties of kopi luwak, from Indonesia. Through gas chromatography and mass spectrometry, the flavor compounds of these coffee varieties were studied and analyzed.

What they interestingly found is that, the digested beans by civet cat did not modify significantly the caffeine, caffeic acid, and quinic acid, the compounds responsible for the coffee’s bitterness. Instead, the level of citric acid in the beans rose significantly, thanks to the work done by the gastric juices and enzymes in the civet cat’s gut. A further study of determining the levels of citric acid, together with malic acid, and the inositol or pyroglutamic acid, could be the key in separating the highly-valued real kopi luwak from regular coffee.

Have you every tried a cup of kopi luwak, the world’s most expensive coffee from Asia? How was it? Did you like the taste? Or are you planning to try one? Either way, share it by leaving a comment below

The post Kopi Luwak (Kape Alamid): The World’s Most Expensive Coffee From Asia appeared first on The Food Untold.

By: Sandman

Title: Kopi Luwak (Kape Alamid): The World’s Most Expensive Coffee From Asia

Sourced From: thefooduntold.com/blog/featured/kopi-luwak-kape-alamid-the-worlds-most-expensive-coffee-from-asia/

Published Date: Sat, 24 Apr 2021 04:17:28 +0000

Read More

0 notes

Text

The Coronavirus Could Finally Kill the Wild Animal Trade

The outbreak may be the push needed to help prevent zoonotic diseases. Animal diseases jump to humans all too easily. Is this a chance to end the trade that fuels it?

— By Lindsey Kennedt, Nathan Paul Southern| February 25, 2020

A vendor sells bats at the Tomohon meat market in Sulawesi, Indonesia, on February 8, 2020.

Ebola. Anthrax. Bubonic plague. HIV. SARS. Coronavirus. You may not be familiar with the term “zoonotic,” but these nightmarish examples fall into that category. Zoonotic diseases are the kinds that can jump the species barrier, and can be particularly dangerous to humans because our immune systems don’t yet know how to fight them.

The COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, for example, probably originates from wild bats, but it’s not yet clear which creature was the intermediary between them and humans. Confiscated samples of pangolin, a critically endangered mammal hunted for use in traditional Chinese medicine, have tested positive for similar strains. Whether or not the intermediary turns out to be a rare, exotic species or a more mundane one such as pigs, one thing is clear: The greater the variety of animals in the same small space, the more pathways there are for diseases to spread and mutate.

This is alarming because the risk of zoonotic disease is rising exponentially. Three-quarters of new diseases in humans are transmitted from animals. The past century has seen ever-expanding human encroachment into natural habitats, exposing people and livestock to more varieties of wild animal than ever before—and with this contact, any bacteria and viruses they carry.

“The more we hunt wildlife, the more we come in contact with new environments and the more we increase the likelihood of us being exposed to these viruses,” explained Peter Ben Embarek of the World Health Organization’s International Food Safety Authorities Network. “It’s clear that poaching and hunting endangered species has to stop. It’s totally unacceptable. I think everybody in all authorities of the world are in agreement with that.”

This is easier said than done. Wildlife trafficking rakes in up to $26 billion per year, helping to make environmental crime one of the four most profitable illegal industries in the world. Chinese demand drives the trade, especially when it comes to rare animal parts like tiger bone, rhinoceros horn, and pangolin scales, all of which are used in traditional Chinese medicine. Until Chinese President Xi Jinping banned public officials from serving shark fin soup and dishes containing wild animals in 2013, it was de rigueur to serve these exotic meats at lavish banquets in China. (Xi acted not out of ecological concern, but as part of a drive to crack down on the appearance of corruption.) Wet markets offering wild meat remained common in China until being shut in the aftermath of the outbreak, while rich tourists continued to travel to places outside Beijing’s direct control, such as the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone situated on the border of Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar (and run by Kings Roman Group, a Hong Kong corporation), where markets openly sell elephant ivory and tiger skins, and critically endangered animals are on the menu. The expense and perceived machismo of such dishes made them particularly attractive to modern China’s culture of conspicuous consumption. This is alarming because the risk of zoonotic disease is rising exponentially.

In the past, the popularity of wildlife products made the Chinese government reluctant to clamp down on the trade. Back in 2003, in the wake of the SARS outbreak, Beijing lifted a ban on sales of palm civets and 53 other species after just four months, only to backtrack when another man in Guangdong contracted the virus in December 2003, and order the destruction of 10,000 civet cats, badgers, raccoon dogs, rats, and cockroaches. The trade temporarily became more covert, but over time it has crept back into the open—and while the import and sale of endangered animals from the wild is illegal, sourcing them from breeding farms is not. This time around, Beijing has fast-tracked a blanket ban on breeding and consuming wildlife products, but whether it lasts remains to be seen.

“I think there will be a period of one or two years where the wildlife trade gets suppressed because of [coronavirus], because people are concerned about it, they don’t know whether it’s legal or not—and the risk of disease,” said Peter Daszak, president of EcoHealth Alliance. “But it will come back, because some of these meals are just so deep in the culture.”

In other words, conservationists have only a small window of time while these fears are still fresh in people’s minds to emphasize the link between the risk of a pandemic and buying and consuming rare wildlife.

If they miss the chance, they will struggle to regain momentum. For decades, environmental campaigners, academics, and policymakers have been at a loss to find the right narrative to end the trade. Highlighting animal cruelty and the destruction of ecosystems resonates with horrified onlookers but has failed to convince actual buyers. “We’ve known about the conservation issues for 50 years. It’s never closed a market,” said Daszak. “The one thing that’s ever closed a market is the emergence of a pandemic: SARS. And now this one.”

Meanwhile, as Vanda Felbab-Brown, author of The Extinction Market, has explained, prohibition alone pushes the trade underground and encourages traffickers to adopt the mindset of smugglers of illicit goods everywhere. As a result, not only do prices rise, but more animals are killed in order to offset the cost of seizures. Fear of prosecution fails to dissuade desperate poachers who need to feed their families in corners of the world where decent jobs are scarce. Legal farming of endangered animals such as tigers spreads confusion among customers about what is and isn’t legal, and is too poorly regulated to mitigate the risk of cross-infection. The civet cats that carried SARS came from farms, not the wild.

A more recent shift in policy has seen the illegal wildlife trade reframed as a serious organized crime phenomenon linked to terrorism financing. This angle attracts international attention and funding but encourages governments to take a military and law-enforcement approach that fails to address the root causes of the trade. As Rosaleen Duffy, a wildlife trafficking expert at Sheffield University, put it: “I don’t see the War on Drugs as having worked at all. So why we think a War on Poachers or a War on the Wildlife Trade will work, I don’t know.”

Ultimately, for as long as there are prospective buyers, the trade will persist. “If there is a demand then the supply will find a way to satisfy that demand,” said Ben Embarek. “It’s not just a matter of banning the trade of wildlife in markets. We also have to convince customers and people going to markets that it’s not appropriate. It’s not a good thing to consume and buy wildlife as food.”

In the long term, the illegal wildlife trade may peter out. Research by EcoHealth Alliance has found that unlike older generations, younger people in China aren’t interested in eating wildlife. The trouble is that we don’t have time to wait around to find out. “I’m sure in 50 years there will be very, very few people in Asia eating wildlife,” said Daszuk. “But this period of 50 years as it disappears is a very dangerous one for the planet.” The other problem is that it may just be that young people don’t have the money or the need for prestige that drives this kind of consumption. But if such dishes can become associated more with pettiness and cruelty than power and success, change might be possible.

So far, as a species, we’ve been lucky. Widespread availability of antibiotics means that, today, even an aggressive and highly contagious bacterial infection such as bubonic plague could be nipped in the bud. Viruses are harder to manage, but to date the most dangerous outbreaks have begun either in countries that are relatively equipped to contain them, such as China, or in places disconnected from major global transport hubs, such as rural Guinea.

It’s only a matter of time, though, until a zoonotic disease emerges that spreads too far and too soon for us to prevent it becoming a global pandemic. The World Health Organization describes this as “Disease X.” Daszak called it “a mathematical certainty.” The coronavirus is looking like a worrying possibility for that, especially after simultaneous outbreaks in Iran, South Korea, and Italy in the past few days.

To be sure, such diseases have emerged and died out in the past, flickering briefly in isolated villages in the jungles or mountains. But that was in a less connected era. After all, an estimated 40 million commercial flights per year help transport emerging diseases to and from every corner of the planet at breakneck speed—and place wealthy, frequent-flier countries at high risk of an outbreak.

“Maybe now’s the time to rethink our relationship with wildlife and leave them in the forests where they belong. Then we won’t get the viruses,” Daszak said. “Bottom line: eating wildlife is bad for your health. That’s the message that’s got to get out.”

— FP

0 notes

Text

Where does luwak coffee come from?

vimeo

Kopi luwak or civet coffee, is coffee that includes partially digested coffee cherries, eaten and defecated by the Asian palm civet. Fermentation occurs as the cherries pass through a civet's intestines, and after being defecated with other fecal matter, they are collected.The traditional method of collecting feces from wild civets has given way to intensive farming methods in which civets in battery cage systems are force-fed the cherries. This method of production has raised ethical concerns about the treatment of civets due to "horrific conditions" including isolation, poor diet, small cages and a high mortality rate.Although kopi luwak is a form of processing rather than a variety of coffee, it has been called one of the most expensive coffees in the world, with retail prices reaching €550 / US$700 per kilogram.Kopi luwak is produced mainly on the islands of Sumatra, Java, Bali and Sulawesi in the Indonesian Archipelago. It is also widely gathered in the forest or produced in the farms in the islands of the Philippines and in East Timor Weasel coffee is a loose English translation of its Vietnamese name cà phê Chồn.

Likes: 0

Viewed:

The post Where does luwak coffee come from? appeared first on Good Info.

0 notes

Text

Coffee-type TOP4- #1: KOPI LUWAK COFFEE

Today we talk about Kopi luwak, the world’s most expensive coffee. The main factor of it’s high price is the uncommon method of producing such a coffee. In fact it has been produced from the coffee beans which have been digested by a certain Indonesian cat-like animal called palm civet. The dropping are collected and then coffee beans are washed, roasted and then brewed to produce what has become the word’s most expensive coffee.

Kopi luwak has traditionally consisted of the best quality, ripest coffee cherries the luwak has selected and chosen to eat while leaving the vast majority of presumably inferior cherries uneaten. This is certainly a major factor in the final quality of the kopi luwak produced. Feeding luwaks coffee cherries to the exclusion of other foods will of course ensure they eat the cherries; however the cherries have not been selected by the luwak and are therefore not of the standard that is produced when the luwak is free to roam a coffee planation. This is why Kopi Luwak must be wild living and non-caged civet cat, collected by farmers and sold to roasters to prepare for human consumption.

Kopi luwak is produced mainly on the islands of Sumatra, Java, Bali and Sulawesi in the Indonesian Archipelago. It is also widely gathered in the forest or produced in the farms in the islands of the Philippines and in East Timo.

Several commercial processes attempt to replicate the digestive process of the civets without animal involvement.Researchers with the University of Florida have been issued with a patent for one such process. Brooklyn-based food startup Afineur has also developed a patented fermentation technology that reproduces some of the taste aspects of Kopi Luwak while improving coffee bean taste and nutritional profile. Vietnamese companies sell an imitation kopi luwak, made using an enzyme soak which they claim replicates the civet's digestive process. Imitation has several motivations. The high price of kopi luwak drives the search for a way to produce kopi luwak in large quantities. Kopi luwak production involves a great deal of labour, whether farmed or wild-gathered. The small production quantity and the labor involved in production contribute to the coffee's high cost. Imitation may be a response to the decrease in the civet population.

Kopi Iuwak can reach 770$ per kg.

0 notes

Text

Where does luwak coffee come from?

vimeo

Kopi luwak or civet coffee, is coffee that includes partially digested coffee cherries, eaten and defecated by the Asian palm civet. Fermentation occurs as the cherries pass through a civet's intestines, and after being defecated with other fecal matter, they are collected.The traditional method of collecting feces from wild civets has given way to intensive farming methods in which civets in battery cage systems are force-fed the cherries. This method of production has raised ethical concerns about the treatment of civets due to "horrific conditions" including isolation, poor diet, small cages and a high mortality rate.Although kopi luwak is a form of processing rather than a variety of coffee, it has been called one of the most expensive coffees in the world, with retail prices reaching €550 / US$700 per kilogram.Kopi luwak is produced mainly on the islands of Sumatra, Java, Bali and Sulawesi in the Indonesian Archipelago. It is also widely gathered in the forest or produced in the farms in the islands of the Philippines and in East Timor Weasel coffee is a loose English translation of its Vietnamese name cà phê Chồn.

Likes: 0

Viewed:

The post Where does luwak coffee come from? appeared first on Good Info.

0 notes