#The Lower Dacha

Text

Grand Duchess Elisabeth Feodorovna of Russia (née Princess of Hesse) with her baby nephew Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich of Russia, The Lower Dacha, Peterhof, 1905

#his little chubby cheeks tho 🥹🫶✨#alexei nikolaevich#elizabeth feodorovna#princess elisabeth of hesse#elisabeth of hesse#tsarevich alexei#alexei romanov#the lower dacha#peterhof#1905

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peterhoff Palace Complex

Photographs: Different views of Peterhof, which, rather than one specific place, is an astoundingly beautiful complex of palaces, gardens, pavilions, and fountains. The photos here and the text are a mere preview of a fraction of the place in all its grandeur.

The Grand Palace, Lower and Upper Gardens and Fountains

The Peterhoff Palace (which comes from the Dutch "Pieterhof," meaning "Pieter's Court") is a complex of palaces, gardens, pavilions, and fountains located in Petergof, Saint Petersburg, Russia, commissioned by Peter the Great in response to Louis XIV Palace of Versailles in France.

Peter the Great began constructing his new capital, St. Petersburg, in 1703 after successfully adding Swedish provinces to Russian territory. Saint Petersburg allowed Russian access to the Baltic Sea through the Neva River that flowed to the Gulf of Finland.

Throughout the early 18th century, Peter the Great built and expanded the Peterhof Palace complex. Based on his sketches, he constructed the Monplaisir Palace (French: "my delight"). This would be Peter's summer retreat that he would use on his way coming and going from Europe. Later, he expanded his plans to include a group of palaces and gardens further inland, on the model of Versailles.

Most of the Peterhoff land is comprised of what is called the "Lower Gardens." In the middle of the lower gardens is the Grand Palace. The area behind this palace is the "Upper Gardens" and is comparatively smaller. The Grand Palace is not the only historic royal building in Peterhoff. The palaces of Monplaisir and Marli, as well as the pavilion known as the 'Hermitage,' were all raised during the initial construction of Peterhoff during the reign of Peter the Great.

There are a number of cascades and fountains through the grounds, which have various symbolic meanings and are in themselves great technological achievements. The greatest of these is that all of the fountains in Peterhoff operate without the use of pumps. Water is supplied from natural springs and collects in reservoirs in the Upper Gardens. The elevation difference creates the pressure that drives most of the fountains of the Lower Gardens.

Gothic Chapel in Peterhof: An Orthodox church in the name of Saint Alexander Nevsky situated in the Alexandria Park; Nicholas I ordered its construction to complement the Cottage Palace

Alexandria Park, the Cottage Palace, and the Farmers Palace

To the east of the main park at Peterhof lies an expanse of landscaped parkland in the English style, named after Alexandra Fedorovna, wife of Nicholas I. The land was used as a royal hunting ground for most of the 18th century and left to go wild after the court moved to Tsarskoe Selo.

In 1825, the land was passed to Nicholas I, who commissioned a Scottish architect and landscape gardener to create an English-style estate with a "cottage" palace and home farm. This was partly a concession to Alexandra (nee Charlotte of Prussia), who found the pomp and grandeur of court life oppressive. Alexandra loved the cottage. The Cottage Palace was completed in 1829 and became the permanent summer residence of the Tsar's family. Alexandria Park is one of the best-landscaped parks on the outskirts of St. Petersburg.

The building is equal parts seaside villa, Gothic castle, and English farmhouse, but extremely elegant, with several charming decorative details. The palace's interiors exemplify the private tastes of Nicholas and Alexandra and their children and grandchildren. The spectacular trompe l'oeil murals around the staircase, depicting gothic arches and vaults, and Nicholas's Naval Study, with superb views over the Gulf of Finland, are particularly impressive.

The Farm Palace was initially a pavilion in Alexandria Park close to the Cottage Palace and Gothic Chapel. Meant to be a pastoral farm with a row of household buildings, it was later expanded into a summer residence for the family of Tsesarevich Alexander Alexandrovich of Russia. The palace became the favorite summer residence of Alexander II and his family. After many reconstructions, the house was named "The Farm Palace" in 1859. It would eventually be a favorite of Alexander III and Nicholas II.

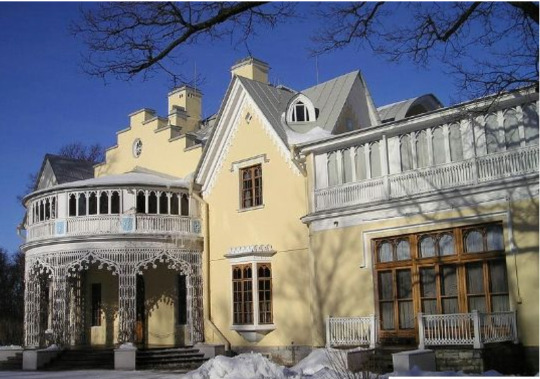

The Lower Dacha at Peterhoff (badly damaged in World War II and destroyed in the 1960s) - in the process of reconstruction

The Lower Dacha was in Alexandria Park, part of the Peterhof complex created by Tsar Peter I in the early 18th century as an Imperial summer residence. The palace was the home of Tsar Nicholas II while in residence at Peterhof (it was built for him), and several of his children were born there. It was badly damaged during the Second World War and was destroyed in the 1960s. The Lower Dacha is in the process of being restored. It is expected that the restoration will be completed by 2025. The picture below where the intact building can be seen, is from the early twentieth century. Photographs of the ruins have been included as well.

#Peter the Great#Sweden#Finland#Upper Gardens#Lower Gardens#Mon Plaisir#Grand Peterhoff Palace#Great Samsom#Neva River#The Farm Palace#The Cottage#The Lower Dacha

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

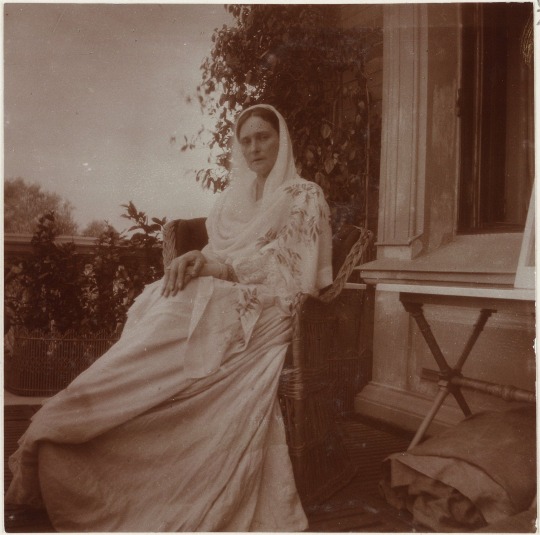

Alexandra Feodorovna at the lower dacha in peterhof, 1909

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Romanov children in front of the Lower Dacha at Peterhof.

#otma#romanov#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#alexei romanov#lower dacha#andrei derevenko

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

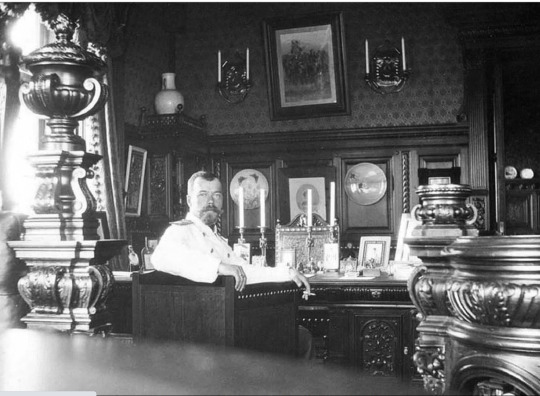

Nicholas II in his studio at the Lower Dacha, Peterhof

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna and Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna at the Lower Dacha in Peterhof, 1908.

#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#grand duchess maria nikolaevna#grand duchess anastasia nikolaevna#history#romanov#1900s#my edits

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Marie and Anastasia Nikolaevna Romanov 1904 at the Lower Dacha in Peterhof. OTMA

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wings (Крылья, 1906) by Mikhail Kuzmin - Part One

It was becoming brighter and brighter inside the somewhat empty train carriage with the morning; through the fogged-up window, the green of the grass, almost venomously vivid despite it being the end of August, the waterlogged roads, the milkmaids’ little carts in front of the lowered barrier, the guard huts, the women at their dachas wandering under colourful umbrellas could all be seen. At the frequent, identical stations, the carriage took on new local passengers with briefcases and it was obvious that the carriage, the railway – for them, these were neither an era, nor even an episode in their lives, but a normal part of daily routine, and the bench upon which Nikolai Ivanovich Smurov was sitting with Vanya seemed like the most solid and significant in the whole carriage. The tightly-fastened suitcases, the cushioned straps, the old gentleman sitting opposite with long hair and an out-of-fashion bag strung over his shoulder – all this spoke to a prolonged journey, less familiar and more era-defining.

Looking now at the reddish sunbeam that blazed intermittently through the clouds of locomotive steam, then at Nikolai Ivanovich’s face, which had taken on a stupid look as he slept, Vanya recalled the rasping voice of this brother of his when, in the hall back there, far away, ‘at home’, he had said to him, “There’s nothing left out of that money of yours from mama; you know, we’re not rich ourselves, but, as a brother, I’m prepared to help you out; you’ve still got a lot of school ahead of you and I can’t take you in, but I’ll settle you in round Aleksei Vasilyevich’s and come and see you; it’s happy there, you can meet a lot of proper people. You keep on trying; Natasha and I would be happy to take you, but it’s decidedly impossible; indeed, you’d be happy at the Kazansky’s: there’s always young people there. I’ll pay for you; when we split up – I’ll take it away.” Vanya had listened, sitting at the window in the hall and watching how the sun lit up the corner of his trunk, Nikolai Ivanovich’s grey and lilac-striped trousers, and the painted floor. He did not attempt to pick up on the meaning of the words, lost in thought about how mama had died, how the house had suddenly filled up with old women, once strangers and now unusually close; he remembered the hassle, the funeral service, the burial, and the abrupt emptiness and solitude after all of this , and, without looking at Nikolai Ivanovich, he simply said mechanically, “Yes, uncle Kolya,” even though Nikolai Ivanovich was not his uncle, only his cousin.

It seemed strange to him now to journey as a pair together with this person who was nevertheless altogether alien to him, to be so close to him for so long, to talk about business and make plans with him. He was also somewhat disappointed, even though he had known this in advance, that they would not arrive immediately in the centre of Saint Petersburg, with its palaces and large buildings filled with sun, people and martial music, coming in through a big archway, and instead, vegetable gardens visible through grey fences, along with graveyards that seemed from afar like romantic groves, and chill, damp multi-storey workers’ tenements set amongst tumbledown shacks all stretched long and far through the smoke and soot. So, this is it – Petersburg! thought Vanya with disappointment and curiosity as he looked at the unwelcoming faces of the porters.

“Have you finished reading them, Kostya? May I?” said Anna Nikolaevna as she stood up from the table and took a bundle of Russian newspapers off Konstantin Vasilyevich with her long fingers, decorated with cheap rings despite the early hour.

“Yes; there’s nothing interesting.”

“What could be interesting in our newspapers? I understand it overseas. You can write anything over there, answering for it in court, if necessary. We’ve got something awful – you don’t know what to believe in. The reports and dispatches from the government are untrue or meaningless, there’s no kind of inner life besides wasting money – just special correspondents’ rumours.”

“But even abroad, there’s only sensationalised rumours and they’re not held accountable before the law for telling half-truths.”

Koka and Boba idly chatted with spoons in their glasses and ate bread with bad butter.

“Whereabouts are you going to be today, Nata? Do you have much to do?” asked Anna Nikolaevna with a slightly affected tone.

Nata – all freckly, with a vulgar, pouting mouth and auburn hair – said something in response through the roll of bread stuffed in her cheek. Uncle Kostya, formerly a cashier at some shady club before being caught with his hand in the till, had been living at his brother’s without a place or business of his own after getting out of prison and was indignant at his trial for embezzlement.

“Now that everything is waking up, new forces are emerging, everything is awakening,” Aleksei Vasilyevich contested hotly.

“I’m not for any awakenings at all; for example, I prefer Sonya’s aunt asleep.”

Students and simply young people of some sort or another were coming and going in their jackets, sharing amongst themselves their impressions, taken from the newspapers, of the horse races that had just been; uncle Kostya called for vodka; Anna Nikolaevna, already in her hat and pulling on gloves, spoke about an exhibition while looking askance at uncle Kostya, who was pouring shots with slightly shaking hands. He cast his kindly, red-tinged eyes about the room and said, “A strike, my friends, this, you know, this, you know…”

“Larion Dmitriyevich!” announced the maid as she quickly went through to the kitchen, picking up a tray with glasses and a dirty, crumpled tablecloth on the way.

Vanya turned away from the window where he was standing and saw coming in through the door the long, well-familiar and baggy-clothed figure of Larion Dmitriyevich Stroop.

Vanya started to comb his hair and spent considerable time occupying himself with his toilette. Examining his reflection in a little mirror on the wall, he looked on with detachment at the somewhat indifferent, round face there, with its flushed colour, big, grey eyes, handsome, but still childishly puckered mouth, and light hair, which, not having been cut short, curled slightly. He neither liked nor disliked this tall, thin boy with thin eyebrows, wearing a loose black shirt. Out the window was the courtyard with its paving slabs slick with water, along with the windows of the opposite wing and peddlers with matches. It was a holiday, and everyone was still asleep. Having risen early out of habit, Vanya sat by the window to await some tea, listening to the sounds of the nearby church and the murmurings of the servants as they put the neighbouring room in order. He remembered holiday mornings there, ‘at home’, in an old quarter of the village, their tidy little rooms with muslin curtains and icon lamps, liturgies, pirogi for lunch – everything all nice and simple, bright and sweet, and he began to grow tired of the rainy weather, of the street organs in the yards, of newspapers over morning tea, of this hazy and uncomfortable life, of warm bedrooms.

Konstantin Vasilyevich, who sometimes dropped by to see Vanya, stuck his head in the door.

“Are you alone, Vanya?”

“Yes, uncle Kostya. Hello! What is it?”

“Nothing. Are you waiting for some tea?”

“Yes. Has auntie not gotten up yet?”

“She’s up, but she hasn’t left, though. She’s in a foul mood, which I suppose means there’s no money. The first sign is how she’s been sitting in the bedroom for two hours – this means that there’s no money. And for what? She’ll have to come out anyway.”

“Does uncle Aleksei Vasilyevich earn a lot? Don’t you know?”

“As much as I need to. And what do you mean, “a lot”? Nobody ever has ‘a lot’ of money.”

Konstantin Vasilyevich sighed and fell silent; Vanya was silent too as looked out of the window.

“What I wanted to ask you, my dear Ivan,” Konstantin Vasilyevich began again, “was whether you had money to spare ‘til the middle of the week; I’ll return it on Wednesday, straight away.”

“Where on earth would I get money from? No, of course not.”

“What does it matter where it comes from? Maybe you know someone who…”

“Really, uncle! Who, exactly, would give me money?”

“So, you don’t have any, then, I take it?”

“No.”

“What a poor state of affairs!”

“And how much were you looking for?”

“Five roubles, not a lot, not a lot at all,” Konstantin Vasilyevich lit back up again. “Maybe it will turn up, eh? Just until Wednesday, how’s about it?!”

“I don’t have five roubles.”

Konstantin Vasilyevich looked on at Vanya with disappointment and conniving and fell silent. Vanya fell deeper into ennui.

“Well, what’s to be done, huh? There’s already a touch of rain… Tell you what, my dearest Ivan, ask Larion Dmitriyevich for money for me.”

“Stroop?”

“Yes, ask him, my dear lad!”

“Why don’t you ask him yourself?”

“He won’t give it to me.”

“Why would he give me some, if he won’t give you any?”

“He will give it to you, believe me; please, my lad, just don’t mention that it’s for me; ask as though you needed the 20 roubles for yourself.”

“I thought it was only 5?!”

“Does it make a difference, how much you ask for? Please, Vanya!”

“Okay, fine. But what if he asks me why?”

“He won’t ask, he’s a clever one.”

“Just be sure to return it, you see.”

“I won’t let you down, I won’t.”

“And why do you think, uncle, that Stroop will give me money?”

“Because I think so!” Konstantin Vasilyevich, smiling, tiptoed out of the room, abashed, yet satisfied. Vanya stood a long time by the window, neither turning around nor looking at the rainy yard, and when he was called to tea, before going into the dining room, he once again took a look in the mirror at his blushing face with its grey eyes and thin eyebrows.

In Greek, Nikolaev and Spielevsky kept Vanya entertained the whole time, turning around and snickering at the desk in front. Before the holidays, lessons would go along on any old lines, and the little aging teacher, sitting on his leg, talked about Greek life without setting any tasks; the windows were open and the tops of the trees, coming into their foliage, and the red façade of some building were visible. Vanya’s urge to get out of Petersburg and into the open air, somewhere far away, grew stronger and stronger. The copper door handles and window latches, the spittoons, all polished to brightness, the cards on the walls, the chalkboard, the yellow paper drawer, the backs of his comrades’ heads, some short-cropped, some curly – all this seemed unbearable to him.

“Sycophantic informers, spies – literally, bearers of figs; when it was still forbidden on pain of a fine to export these products from Attica, these people, blackmailers, as we would have it, showed from under their cloaks a fig to the suspect, as a threat, in case he didn’t pay a bribe…” And Daniil Ivanovich, without moving from his chair, demonstrated by gestures and mimicry the informers and the defamed and the cloak and the fig; then, leaping from his seat, he walked about the classroom anxiously repeating the same thing, something along the lines of, “Sycophants … yes, sycophants … yes, gentlemen, sycophants!”, applying a different, yet entirely unexpected, inflection on each word.

I’ll try and ask Stroop for that money today, thought Vanya, looking out the window.

Spielevsky, finally reddened, arose from the desk:

“Why’s Nikolaev molesting me?!”

“Nikolaev, why are you molesting Spielevsky?”

“I’m not molesting him.”

“Then what are you doing?”

“I’m tickling him.”

“Sit down. And you, Master Spielevsky, I advise you to be more precise in your verbiage. Taking into consideration that you are not a woman, Master Nikolaev cannot molest you, being a young man, already of age and of rather limited notions.

“I put the question like this: if you want to work, work; if not, then don’t!” said Anna Nikolaevna with such airs as if the interest of the entire world were fixed upon how she put the question. In the parlour, decorated length and breadth with period furniture in the image of seated bathtubs, Bath chairs and drawers for papers, it was loud with four female voices: those of Anna Nikolaevna, Nata and the Speier sisters – artists.

“I really love this cupboard, but the bench doesn’t do anything for me. I would always prefer a wardrobe.”

“Even if you needed furniture for sitting on?”

“They rail against how the maid is overworked: she goes for a walk more than we do! Sometimes I go days without leaving the house, while our dear Anna, how many times does she manage to go out to the store? Never mind whether it’s for bread or boots. And besides, interacting with people is too big a task. I find all these commiserators’ complaints exaggerated.”

“Imagine, he postures about in such a mood that the girl students are afraid to sit near him. And he’s a most interesting personality, besides: a Russian gypsy from Munich; he’s been to the Gymnasium, the ballet, he’s done modelling; he has some very amusing details about Stuck.”

“It would be too bright in pink foulard. I’d prefer a pale yellow.”

“We should ask Stroop about this.”

“But he left yesterday, did Stroop, you poor things!” cried the elder Speier.

“What, Stroop left? Where to? What for?”

“Well, that I can’t really tell you: as usual, it’s a secret.”

“Who did you hear this from?”

“I heard it from he himself; he said three weeks.”

“Well, that’s not too frightful.”

“Today, Vanya Smurov was also asking when Stroop would be here with us.”

“But what does he have to do with it?”

“I don’t know, business of some kind.”

“Vanya has business with Stroop? How original!”

“Well, Nata, it’s time for us to go,” Anna Nikolaevna tried to chirp up, and both ladies, with skirts rustling, withdrew, convinced that they very much resembled the high-society ladies of the novels by Prévost and Ohnet which they read in translation.

In April, the question of the dacha was raised. Aleksei Vasilyevich needed to be in city frequently, almost daily; Koka and Boba as well, and Anna Nikolaevna and Nata’s plans with regards to the Volga hung in the air. They were vacillating between Terijoki and Sestroretsk, but, regardless of the location of the dacha, they were all concerned about their summer dresses. Dust floated in the open window and the hum of traffic and the sounds of horse-drawn trams could be heard.

Vanya sometimes left for the Summer Garden to do his preparatory reading for his classes. Sitting on the outermost path to the Field of Mars with his little yellow-pink volume of Teubner’s publications laying open, cover side up and already grown slightly and pale from his spring tan, he watched the passers-by in the garden and on the other side of the Lebyazhoi ditch. The laughter of the children in the Krylovskaya playground reached him from the other end of the garden and he didn’t hear the sound of Stroop’s footsteps in the sand as he approached.

“Studying?” said the latter as he lowered himself onto the bench next to Vanya, who thought to limit himself to a bow.

“Yes, I’m studying. You know how boring this is, it’s simply a nightmare!”

“What is it, Homer?”

“It’s Homer. This Greek especially.”

“You don’t enjoy Greek?”

“Who does enjoy it?” smiled Vanya.

“That’s a terrible shame!”

“What is?”

“That you don’t enjoy languages.”

“Living ones I enjoy, you can read something, but who’s going to read them in Greek, this antediluvian stuff?”

“What a child you are, Vanya. The whole world, worlds are closed off to you; besides, to not only know, but love the world of beauty – that is the foundation of any education.”

“But it takes so much time to learn grammar, when you could just read the translations!”

Stroop regarded Vanya with an infinite regret.

“Instead of a person made of flesh and blood, smiling or frowning, who you could love, kiss, hate, in whose veins you could see the blood flowing and the natural grace of the nude body, to have a soulless doll, usually made by a craftsman’s hands – that’s what translations are. And it really doesn’t take much time to learn the preparatory grammar. You just need to read, read, read. Read while looking up each word in the dictionary, picking your way through like a thicket of trees and you will find a pleasure you have never experienced. And it seems to me that you have in yourself the potential to remake yourself into a real, new person, Vanya.”

Vanya remained silent in discontent.

“You are poorly surrounded, but this could be for the best, depriving you of the prejudices of any normal life, and you could make yourself a completely modern person, if you wanted,” added Stroop, who had been silent a moment.

“I don’t know, I’d like to get somewhere away from all of this: away from the Gymnasium, and Homer, and Anna Nikolaevna – that’s all.”

“Into the bosom of nature?”

“Exactly.”

“But, sweet friend of mine, if you living in the bosom of nature means eating more, drinking milk, bathing and not getting up to much, then of course that’s very simple; but to take pleasure in nature may as well be harder than Greek grammar, and, like all pleasures, wears out. And I will not believe a person, who, looking in the city upon the best parts of nature – the sky and the water – with indifference goes to look for nature on Mont Blanc; I will not believe that he loves nature.

Uncle Kostya offered Vanya a ride in the cab.

The proximity of summer could already be felt in the heat of the morning and the streets were half-obstructed with obstacles. Uncle Kostya, taking up three quarters of the cab, sat down assertively, with his legs apart.

“Uncle Kostya, wait a little bit and I’ll just found whether the priest has come, and if he hasn’t, I’ll go with you as far as it suits you and then I’ll go the rest of the way on foot, rather than sit in the Gymnasium. Is that alright?”

“But why shouldn’t your priest have come?”

“He’s been ill for a week.”

“Ah, well alright, go ask.”

Within a minute, Vanya had left and having gone around the cab, sat on the other side, next to Konstantin Vasilyevich:

“It’s as if Larion Dmitriyevich had a feeling, brother, about the kinds of plans we were drawing for him – he left and he never came back, either.”

“He might have come back.”

“Then he would come to Anna Nikolaevna.”

“Who is he exactly, Uncle Kostya?”

“Who’s who, exactly?”

“Larion Dmitriyevich.”

“Stroop – and nothing more. Half-English, a rich man, he doesn’t serve anywhere, he lives well, excellently even, both educated and well-read to the highest degree, so I don’t understand at all why he’s at the Kazanskys’.”

“He’s not married, right, Uncle?”

“It’s the complete opposite, in fact, and if Nata thinks that he’d be tempted by her, she’s sorely mistaken; and anyway, I absolutely do not understand what he has to do round the Kazanskys’? Yesterday was a great laugh: Anna Nikolaevna went to battle with Aleksei!”

They crossed the bridge over the Fontanka. Muzhiki were hoisting fish out of hatches in the fishponds, the steamboats smoked, and the crowd stood idly by around the stone rampart. An ice cream seller was grunting as he pushed his blue container.

“So, did you perhaps hear from somebody that Stroop returned, or did you see him yourself?” said Uncle Kostya at the moment of their farewell.

“No, where could I even have got that from, since you said he hasn’t arrived” said Vanya, blushing.

“And here you said it wasn’t hot and you’re so red yourself,” and Konstantin Vasilyevich’s corpulent body hid itself within the entryway.

Why did I hide my meeting with Stroop from him? thought Vanya, glad that he was keeping some kind of secret.

The staffroom was hazy with cigarette smoke and the cups of weak tea were becoming slightly scummy in the dim ground-floor room. To a person coming in, it appeared as though the figures were moving about as in an aquarium. The torrential rain pouring outside the opaque windows strengthened this impression. The sound of voices, the chink of little teaspoons mingled with the muffled din of the breaktime that reached the room from the hall and, with time, from even closer – the corridor.

“Orlov is being given a hard time by sixth class again; he really doesn’t know how to apply himself.”

“Well, ok, let’s suppose you give him a bad grade, he stays around – do you think that that will fix him?”

“I’m not at all looking to set corrective targets, I’m trying to give a proper judgement of their knowledge.”

“Our students would be terrified if they saw the programmes for French colleges, let alone the seminars.”

“I doubt Ivan Petrovich would be satisfied with that.”

“Incomparable, I tell you, incomparable; yesterday his speech was outstanding.”

“You’re good as well, going for the small in clubs while you have a king, jack and two small ones.”

“Spielevsky is a little reprobate, and I don’t understand why you stand up for him like this.”

All voices were silenced by the sharp tenor of the inspector, a Czech man with pince-nez and a grey, pointed beard.

“Then I will remind you, gentlemen, to pay attention to the ventilation window; never above fourteen degrees, draught and ventilation.”

They gradually went their different ways and only the quiet bass of the Russian teacher chatting with the Greek resounded through the emptying staffroom.

“You come across some interesting types here. In summer, before enrolment, they had some reading to do, a fair amount, and, for example, The Demon[1] – here’s how they render it ex abrupto: ‘The Devil was flying over the earth and saw a girl’ – What was the girl called? – ‘Liza’ – Let’s say Tamara. – ‘Fine, Tamara.’ – Well, what then? – ‘He wanted to marry her, but her husband intervened, then the husband was killed by Tatars.’ – So did the Demon go on to marry Tamara? – ‘There was no way, an angel got in the way, crossing the road, so the Devil remained single and hated everything.’”

“Magnificent, in my opinion…”

“Or this review of Rudin:[2] ‘There was this rubbish guy, who said a lot and didn’t do anything, then he got mixed up with some shallow people who killed him.’ – So why, I ask, do you think the workers, and in general all the members of the people’s movement in which Rudin died, are shallow people? – ‘That’s right,’ he answers, ‘he suffered for the truth.’”

“You’re trying in vain to get a personal opinion out of this young person about what he’s read. Military service, like a monastery, like almost any preconfigured doctrine, has a huge appeal in the availability of ready-made and fixed attitudes to any kind of phenomena or concepts. For weak people, this is a big support, and life becomes unusually easy, lacking in ethical creativity.”

In the corridor, Vanya was laying in wait for Daniil Ivanovich.

“What can I do for you, Smurov?”

“I’d like to speak with you, Daniil Ivanovich, in private.”

“What about?”

“About Greek.”

“Aren’t you doing well?”

“No, I have a 3+.”

“So what do you want?”

“No, I’d rather like to speak with you about Greek, and please, Daniil Ivanovich, let me come to your apartment.”

“Yes, of course, of course. You know my address. Although, this is more than noteworthy: someone who’s got it all going well and wants to speak in private about Greek. I live alone, please, I’m at your service from seven till eleven.”

Daniil Ivanovich started to climb the stairs, but stopped and shouted after Vanya, “Hey, Smurov, just to say: I’m still at home after eleven but I’ll have gone to bed and am only capable of the most private explanations which I’m sure you don’t need.”

Vanya met with Stroop in the Summer Garden more than once and, without realising himself, came to lay in wait for him, always sitting by the same path and leaving when he could not abide the wait with an easy, albeit deliberately slow, gait, carefully scrutinising the male figures which resembled Stroop. One time, however, after not meeting Stroop, he went for a walk around part of the garden where he had never been before and met Koka, who was going for a walk in an unbuttoned coat over a mess jacket.

“There you are, Ivan! What are you doing, going for a walk?”

“Yes, I’m here fairly often. What of it?”

“Why do I never see you then? Do you sit somewhere on the other side, is that it?”

“Wherever possible.”

“Whenever I bump into Stroop, it’s over there and I wonder – is it not for the same thing that we come here?”

“Stroop’s arrived?”

“A little while ago. Nata and all the rest know, and however a fool Nata may be, it’s still swinish of him to not have come to visit us, as though we were some kind of trash.”

“What does Nata have to do with it?”

“She’s trying to reel him in, but she’s barking up completely the wrong tree: he’s not one to get married, not to Nata, anyway; I think with one Ida Golberg he has purely aesthetic discussions and that I’m worrying for nothing.”

“You’re worried?”

“Since I’m in love!” Forgetting that he was talking with Vanya, who did not know his affairs, Koka burst into life, “A strange girl, educated, a musician, a beauty, and how rich! It’s just that she’s lame. And so, I come here every day to see her; she walks here from three to four and I worry whether Stroop’s not here for the same reason.”

“You think Stroop could also be in love with her?”

“Stroop? Well, you can stop right there, he wouldn’t know his head from a hole in the ground! All he does is talk, while she practically worships him. Being in love for Stroop is an utterly, completely different realm.”

“You’re just angry, Koka!”

“Stupid!”

They had just turned by the bed of red germaniums when Koka pronounced, “There they are!” Vanya saw a tall girl, with a pale, round face, lustrous hair, an Aphrodisiacal cut of grey eyes, now blue with excitement, a mouth from a Botticelli painting, in a dark dress; she walked, limping and holding onto an old lady’s arm, while from the other side Stroop was saying, “and the people saw that any beauty, any love from the gods and they became free and courageous and grew wings.”

In the end, Koka and Boba procured a box for Samson and Delilah, but the first showing was replaced by Carmen, and Nata, on whose insistence this activity had been decided upon in the hopes of meeting Stroop on neutral ground, tossed and turned in the knowledge that he would not come to such a well-known opera as this without a good reason. She let Vanya have her place in the box, such that if she arrived at the theatre in the middle of the performance, he would go home. Anna Nikolaevna together with the Speier sisters and Aleksei Vasilyevich set off in cabs while the young people went forth on foot.

Carmen and her friends were already folk dancing with Lillas Pastia when Nata, finding out as though by divine inspiration that Stroop was in the theatre, appeared all in blue, powdered and agitated.

“You’re dismissed then, Vanya.”

“I’ll stay until the end of the act.”

“Is Stroop here?” asked Nata in a whisper, sitting next to Anna Nikolaevna. The latter silently shifted her gaze to the box where Ida Golberg was sitting with an old lady, an officer rather on the young side, and Stroop.

“It’s just a premonition, a premonition!” said Nata, opening and closing her fan.

“You poor creature!” sighed Anna Nikolaevna.

During the entr’acte, Vanya was getting ready to go when Nata stopped him and called him into the foyer.

“Nata, Nata!” Anna Nikolaevna’s voice rang out from the depths of the box, “Would that be proper?”

Nata rushed tempestuously down below, carrying Vanya away with her. Before going into the foyer, she stopped by a mirror to fix her hair and then went into the hall, which was not yet fully populated by audience members. They met Stroop: he entered into discussion with the same young officer who had been in the box, not noticing Smurov or Nata, and even exited straight after for a neighbouring passageway, where a frizzy-haired saleswoman was bored behind a desk with photographs.

“Let’s get out of here, it’s frightfully stuffy!” said Nata, dragging Vanya after Stroop.

“We’re closer to the spot from that exit.”

“I don’t care!” the girl raised her voice as she quickened her pace and almost pushed the audience members aside.

Stroop saw them and stooped over the photographs. Drawing even with him, Vanya loudly hailed, “Larion Dmitriyevich!”

“Ah, Vanya!” The latter man turned around, “Natalya Alekseevna, forgive me, I did not notice you at first.”

“I didn’t expect you to be here,” began Nata.

“Why not? I dearly love Carmen, and it never bores me: there is a deep and true pulse of life in it, all filled with sunlight; I understand that Nietzsche might have been interested in this music.”

Nata listened silently, regarding the speaker with spiteful, red eyes, and pronounced:

“I’m not surprised by meeting you at Carmen, but by the fact that I saw you in Petersburg and not round ours.”

“Yes, I arrived two weeks ago.”

“That’s very nice.”

They began to walk along the empty corridor past drowsing footmen, and Vanya, stood by the staircase, watched with interest Nata’s face, the way it became increasingly covered in the red blemishes, and the gruff physiognomy of her cavalier. The entr’acte ended and Vanya quietly began to climb the staircase to the balcony in order to dress and go home when suddenly he was overtaken by Nata, almost running, with her handkerchief to her mouth.

“It’s disgraceful, you hear, Ivan, disgraceful the way that person spoke to me,” she whispered to Vanya and ran upstairs. Vanya wanted to say goodbye to Stroop and after having stood around on the staircase for some time, he descended to the lower corridor; there, by the door to the box, stood Stroop with the officer.

“Excuse me, Larion Dmitriyevich,” said Vanya, making as though he were going upstairs to his room.

“You can’t be leaving?”

“Well, it wasn’t my own seat, you see; Nata arrived, I was the excess.”

“What’s with this silliness, come to us in our box, we have a free spot. The next act is one of the best.”

“Is it not a problem if I go to the box? I’m a stranger.”

“Of course, it’s nothing: Golberg is a simple person and you are still a boy, Vanya.”

As they entered the box, Stroop bent down to Vanya, who listened to him without turning his head:

“And then, Vanya, I may not be around the Kazanskys’; so, if you don’t mind, I would always be very happy to see you round mine. You could say that you’re studying your English with me; nobody will ask where and why you’re going. Please, Vanya, come.”

“Very well. Did you really break things off with Nata? You’re not going to marry her?” asked Vanya without turning his head.

“No,” said Stroop seriously.

“That’s very good, you know, that you’re not marrying her, because she’s terribly repulsive, a complete frog!” Vanya suddenly burst into laughter, turned to face Stroop fully and for some reason unknown to him, took his hand.

“It’s interesting, how much we see what we want to see and understand what it is we look for. As with the Greek tragedians, the Romans and the Romance peoples of the 17th century saw only three unities, the 18th century – stentorian tirades and ideas of liberation, the Romantics – deeds of the highest heroism and our century – a sharp tinge of primitiveness and Klinger’s illumination of the distances…”

Vanya listened while looking around the room still flooded with evening sunlight. On the walls were shelves upon shelves of unbound books, books on the tables and the chairs, a cage with a thrush, a paralysed kitten on the leather sofa and in the corner, a small bust of Antinoös standing alone, like a household deity of this abode. Daniil Ivanovich, in low felt shoes, fussed over the tea and took cheese and butter in little papers out of the iron stove, and the kitten, without moving its head, followed the movements of its owner with green eyes. And where did we get the idea that he’s old, when he’s really quite young, thought Vanya, examining the bald head of the young Greek with wonder.

“In the 15th century, an enduring view of Achilles’ friendship with Patroclus, and Orestes’ with Pylades as sodomitic love had already been established, whereas there is no direct reference to this in Homer.”

“What, so the Italians thought this up themselves?”

“No, they were right, but the point is that it’s only a cynical attitude towards love of any kind which turns it into debauchery. Am I acting morally or immorally when I sneeze, wipe away dust or stroke a kitten? However, these actions could be criminal, if, say, I warn a murderer by a sneeze of a suitable time for the murder and so on. Committing the murder in cold blood, without malice, deprives the act of any ethical nuance, save the mystical communion between murder and victim, lovers, mother and child.”

It was getting altogether dark and out the window, the rooves of the houses and the faraway Isaac cathedral could hardly be seen in the dingy pink sky, obscured by smoke.

Vanya began to get ready to go home; the kitten began to hobble about on its crippled front paws, disturbed by Vanya’s cap, upon which it had been sleeping.

“You must be a kind man, Daniil Ivanovich: you take care of different cripples.”

“He likes me, and I enjoy having him. If doing what brings me satisfaction means I’m kind, then so I am.”

“Tell me, please, Smurov,” said Daniil Ivanovich, shaking Vanya’s hand farewell, “did you come up with idea to come to me for Greek discussions all by yourself?”

“Yes, that is, the thought perhaps came to me from another person.”

“Who was it, if it’s not a secret?”

“No, why would it be? It’s just that you don’t know him.”

“And what if I did?”

“A certain Mr Stroop.”

“Larion Dmitriyevich?”

“You really know him?”

“Very well, even,” answered the Greek, lighting the way Vanya’s way to the staircase with a lamp.

Nobody was in the locked cabin on the Finnish steamboat, but Nata, worried about a draught, led the whole company there anyway.

“Absolutely, absolutely no dachas!” said Anna Nikolaevna, exhausted. “There’s such foulness everywhere: holes in the walls, the wind blowing!”

“The wind always blows at dachas – what did you expect? You weren’t born yesterday!”

“Do you want one?” Koka offered Boba his open cigar case, open, with a nude woman on it.

“It’s not the dacha itself being foul that makes it foul there, it’s because you feel like you’re on bivouac, temporarily surviving without an established life, while in the city you always know what needs doing and when.”

“And what if you were to live at the dacha all the time, summer and winter?”

“Then it would not be disgusting; I’d establish a routine.”

“True,” Anna Nikolaevna picked up the thread, “I wouldn’t want to get settled down for a while. For example, the summer before last we put new wallpaper up – so that it was all pristine when it came to give it back to the landlord; not to tear it all down!”

“Do you wish, then, that you hadn’t smeared it?”

Nata looked out of the window with a grimace at the palaces and golden-pink, wide and smoothly spreading waves, all burning in the sunset.

“And then there’s a mass of people, everyone knows about each other, what they cook, how much they pay the servants.”

“How abominable!”

“What are you going for?”

“What do you mean, what for? Where else should I disappear off to? Should I stay in the city, or what?”

“And what of it? At least, when it’s sunny, you can walk on the shaded side.”

“Uncle Kostya’s always making things up.”

“Mama,” Nata suddenly turned around, “my dear, let’s go to the Volga; there’s little towns there, Plyos, Vasilsursk, where you can set yourself up for not a lot of money. Varvara Nikolaevna Speier was saying… They lived in Plyos with a whole entourage, you know, Levitan also lived there; they in Ugilch as well.”

“Well, as it seems, they were thrown out of Ugilch,” responded Koka.

“Well then, they were thrown out, what of it? They won’t throw us out! Of course, the landlords said to them: ‘you have a whole entourage, young ladies, suitors, ours is a quiet town, nobody goes travelling around, we’re afraid: if you’ll forgive us, but clear out the apartment.’”

They were approaching the Aleksandrovsky Garden. In the lower windows of the wharf, a brightly lit kitchen was visible, a sculleryman, all in white, past the cleaning sailor, a blazing stove in the depths.

“Auntie, I’ll be going from here to Larion Dmitriyevich,” said Vanya.

“Go on, then; you’ve found a comrade here as well!” grumbled Anna Nikolaevna.

“So he’s a bad person?”

“I didn’t say that he’s a bad person, just that he’s not a comrade.”

“I’m practising English with him.”

“It’s all rubbish, you’d do better to prepare for your lessons…”

“No, I’m still going, you know, Auntie.”

“Well go, who’s keeping you?”

“Make sure to give your Stroop a kiss,” added Nata.

“Maybe I will, no-one’s bothered about it.”

“Perhaps we should,” started Boba, but Vanya interrupted him, flying at Nata:

“I bet you’d love to kiss him, while he doesn’t want you because you’re a ginger little frog, you’re an imbecile! Yeah!”

“Ivan, pack it in!” Aleksei Vasilyevich’s voice rang out.

“Why do they have it in for me? Why don’t they let me go? Because I’m small? I will write to uncle Kolya tomorrow!”

“Ivan, stop it,” exclaimed Aleksei Vasilyevich with a higher tone.

“Such a little boy, you pig, daring to behave like that!” Anna Nikolaevna was alarmed.

“And Stroop will never, ever, ever marry you!” blurted Vanya, besides himself.

Nata immediately abated and, almost calmly, said quietly:

“Will he marry Ida Golberg then?”

“I don’t know,” simply answered Vanya, also quietly. “It’s not likely, I don’t think,” he added, almost tenderly.

“Here’s another argument kicking off!” cried Anna Nikolaevna.

“What, do you mean you believe that boy?”

“Perhaps I do believe him,” grumbled Nata, turning to the window.

“Hey, you, Ivan, you mustn’t think they’re such little idiots as they want to appear,” Boba urged Vanya. “They’re overjoyed that through you they get to have dealings with Stroop and updates on Golberg; only, if you really are attached to Larion Dmitriyevich, be careful not to betray yourself.”

“In what way would I betray myself?” Vanya was surprised.

“My advice has been taken on board so quickly?!” Boba began to laugh and stepped onto the wharf.

When Vanya entered Stroop’s apartment, he could hear singing and piano. He quietly went to the study on the left of the hallway, without going into the parlour, and began to listen. A male voice, unknown to him, sang:

The piano shrouded the agonising phrases of the voice with low chords, like a thick fog. An intermittent discussion between masculine voices broke out, and Vanya went out into the hall. How he loved this spacious, green room, resounding with the sounds of Rameau and Debussy, and these friends of Stroop’s, so unlike the people he met at the Kazanskys’; the debates; the late dinners with men with wine and light discussion; the study with books up to the ceiling where they read Marlow and Swinburne, the bedroom with the washbasin, where dark red fauns danced around with a garland on the bright green background; the dining room, all in red copper; the tales about Italy, Egypt, India; the rapturous delights borne from the poignant beauty of all countries and all times; the walks around the island; the confusing but enticing reasonings; this smile on this unattractive face; the smell of peau d’Espagne, wafting putrefaction; these thin, strong fingers in signet rings, boots on an unusually wide sole – how he loved all of this, engrossed vaguely without understanding.

The evening gloom over a hot sea,

The fires of lighthouses in the darkening sky,

The scent of vervain at the end of the banquet,

A fresh morning after long vigils,

A walk along the paths of a springtime park,

The cries and laughter of bathing women,

Sacred peacocks at the temple of Juno,

Merchants of violets, pomegranates and lemons,

The doves coo, the sun shines,

When I see you, my native town!

“We are Hellenes: the intolerable monotheism of the Judaeans is alien to us, as is their turning their backs on the visual arts, together with their attachment to the flesh, to offspring, to family. In the whole Bible, there is no indication of a doctrine of bliss in the afterlife, and the only reward mentioned in the commandments (and specifically in honour of those who have given life) is to live long years upon the earth. A childless marriage is a stain, a curse, depriving one of the right to participation in public worship, as though forgetting that in Jewish legend, the childbed and labour are punishments for sin, not the point of life. And the further people are from sin, the further they will be from childbirth and physical labour. This is vaguely understood by Christians, when a woman cleanses herself with prayer after birth, but not after marriage, and a man is not subject to anything similar. Love has no purpose besides itself; nature is also free from any shadows of an idea of finality. The laws of nature are an entirely separate category than the so-called divine laws and the human ones. The law of nature is not that a given tree must bear fruit, but that under certain conditions, it will bear fruit and under others, it will not and will even perish as justly and simply as it would have borne fruit. Upon the entry of a knife, the heart stops beating: there is no finality here, nor good, nor evil. And the laws of nature can only be broken by he who can kiss his own eyes without tearing them from their sockets, and can see the nape of his neck without a mirror. And when they say ‘unnatural’ to you, you just look at the blind person speaking and pass on by, without becoming one of those sparrows that flies from the scarecrow in the vegetable patch. People go about like blind beggars, like corpses, when they could be creating the most ardently bright lives, where all pleasures would be so intense that it would be as though you had just been born and now, you’re dying. Everything must be perceived with this kind of greed. Miracles are around us at every step: there are muscles, ligaments in the human body, that it’s impossible to look upon without awe! And connecting the notion of beauty to the beauty of a woman to a man is nothing but vulgar lust, and far, far away indeed from a true idea of beauty. We are Hellenes, lovers of the beautiful, bacchantes of the coming life. Like Tannhauser’s visions in Venus’ grotto, like the premonitions of Klinger and Thomas, there is a primeval homeland, flooded with sun and free, with beautiful and courageous people, and there, beyond the sea, through shadow and fog, we go, Argonauts! And in this unheard-of novelty itself, we shall discover the most ancient roots, and in the unseen radiances themselves we shall feel our homeland!”

“Vanya, could you take a look in the living room and see what the time is, please?” said Ida Golberg, laying some kind of colourful needlework down on her knee.

The big room in the new house resembled a brightly lit cabin on the deck of a ship and was scantly furnished with simple furniture: a yellow curtain that covered the whole wall was drawn across three windows at once, and on the leather trunk; suitcases yet to be packed, lined with little brass nails; a chest with late hyacinths fell an unsettling yellow light. Vanya put down the Dante that he had been reading aloud and went into the neighbouring room.

“Half past five,” he said, returning. “Larion Dmitriyevich has been gone a long time,” he declared, as though responding to the girl’s thoughts. “Are we going to stop studying?”

“It’s not worth starting a new canto, Vanya. And so:

And he saw how with smiles they listened to the final conclusion, then turned towards the beautiful lady.

E vidi con riso

Udito havevan l’ultimo construtto;

Poi a la bella donna tornai il viso’’[3]

“Is a beautiful lady the contemplation of an active life?”

“Vanya, you must never fully believe the commentary, besides the historical information; understand simply and beautifully – that’s all; otherwise, to tell the truth, some kind of mathematics emerges instead of Dante.”

She finally put away her work and sat as though waiting for something, tapping a split knife on the handle of the table.

“Larion Dmitriyevich will arrive soon, most likely,” declared Vanya almost patronisingly, again catching the girl’s thoughts.

“You saw him yesterday?”

“No, I didn’t see him yesterday, nor three days ago. Yesterday, he went to Tsarskoe in the day, and in the evening, he was at the club, while three days ago he went somewhere on Vyborgskaya, I don’t know where," revealed Vanya respectfully and proudly.

“To see whom?”

“I don’t know, business of some kind.”

“You don’t know?”

“No.”

“Listen, Vanya,” the girl started, looking at the little knife, “I’m asking you – not for me alone, for you, for Larion Dmitriyevich, for us all – find out what that address is? It’s very important, very important for all three of us,” and she passed Vanya a scrap of paper where, in Stroop’s sprawling, sharp handwriting, it was written: “Vyborgskaya, Simbirskaya St. No. 36, Apt. 103, Fyodor Vasilyevich Solovyov.”

No-one was particularly surprised that, besides his other interests, Stroop also took up the study of Russian antiquity; that he began to be visited by either loquacious men in German dress, or by old “by God!”-types in full-length half-kaftans, but all the same, crafty merchants with manuscripts, icons, antique fabrics, a counterfeit mould; that he began to take an interest in ancient singing, to read Smolensky, Razumovsky and Metallov, to sometimes go listen to Nikolaevskaya’s singing and, finally, under the direction of some pockmarked chorister, learned his hooks.[4]

“I’ve been completely unaware of this little backstreet of the world’s soul,” repeated Stroop, trying to infect Vanya as well with this hobby, who, to his surprise, was susceptible to this particular direction.

Once, Stroop announced over tea:

“Well, Vanya, you must see this without delay: an authentic Raskolnik[5] from the Volga, of an old breed, imagine: 18 years old, and he goes about in a long coat, cinched at the wait, he doesn’t drink tea; his sisters live in a monastery hermitage; a house on the Volga with a tall fence and chained-up dogs, where they go to sleep at 9 P.M. – something in the Vein of Pechersky, only less saccharine. You must see this, without delay. Let us go to Zasadin tomorrow, he has an interesting “Apotheosis”; our man will arrive there, and I’ll introduce you. Oh, by the way, write down the address just in case; maybe I’ll go straight there from the exhibition and it’ll pass to you to find him yourself.” And Stroop, without looking in his notebook, as it was already well-known to him, dictated, “Simbirskaya, No. 36, Apt. 103, the furnished rooms – ask there.”

The muffled sound of two voices speaking was audible from behind the door; a clock with weights quietly ticked; dark icons and leatherbound books were piled on the tables, the chairs and the windowsills; it was musty and dusty, and from the corridor, through the ventilation window above the door came the putrid odour of sour shchi.[6] Zasadin, standing in front of Vanya and putting on a kaftan, said:

“Larion Dmitriyevich won’t be here for at least forty minutes, perhaps even an hour; I need to go and get an icon, but, well, I don’t know how it will turn out? Will you wait here, or are going to go somewhere?”

“I’ll wait here.”

“Well, well, I’ll be back right away. Here are some books to interest yourself with until then,” and Zasadin, after giving Vanya a dusty Leimonarion, hurriedly secreted himself through the door, whence came the strong stench of sour shchi. Vanya, stood by the window, opened on a tale, recounting how a certain old man, after a chance meeting with a woman who lived alone in the same desert, kept returning to lascivious thoughts about that same woman, and, not being able to endure it, took up a staff in the scorching heat and set out, stumbling like a blind man out of lust, to the place where he thought to find this woman; and, as in a delirium, he saw the earth open up and there, within it, were three decomposing bodies: a woman, a man, and a child; and there was a voice, “Here is a woman, here a man, here a child – who now can distinguish them? Go and enjoy your lust.”[7] Everyone, everyone is equal before death, love and beauty, all bodies are wonderfully identical and only lust drives a man to chase after women, and a woman to wait for a man.

On the other side of the wall, a young, quite hoarse voice continued:

“Well, I’ll leave, uncle Yermolai, why do you keep calling me names?”

“How could I not, you slacker! Taking it into your head to fool around!”

“Uh-huh, Vaska might have told you a load of lies; what have you heard about him?”

“Why would Vaska lie? Well, tell me yourself, deny it yourself: you don’t really fool around?”

“And what of it? Yeah, I fool around! But Vaska doesn’t? Near enough everyone fools around round ours, except Dmitri Pavlovich,” and it was audible how the one speaking started to laugh. Having quietened down, he began again with a more intimate tone, sotto voce, “It was Vaska himself who taught me; a young master arrived once and he says to Dmitri Pavlovich: ‘I wish to be washed by the one who let me in,’ and it was me who let him in; but as Dmitri Pavlovich knew that this master was one who liked to play around and it was always Vasily who took care of him before, he says, ‘I’m afraid that it won’t be possible, your grace, to go with him alone: he’s not a regular and does not understand any of this.’ – Well, to Hell with you, make a pair with Vasily! – that’s how Vaska came in and he says, ‘How much are you proposing us?’ – Besides the beer, ten roubles. – We have a rule: whoever draws the curtain across the doorway will be fooling around, and the monitor is not allowed to take out less than five roubles; Vasily said, ‘No, your excellency, we can’t shake hands on that.’ – He offered another tenner. Vasya went to go and get the water ready, and I started to get undressed, while the master said, ‘Hey, what’s that you have there on your cheek, Fyodor? A birthmark, or some dirt?’ – He laughs and reaches his hand out. And I just stand there? Like an idiot, I don’t know myself whether or not I’ve got a birthmark on my cheek. However, here’s Vasily, so angry, he comes and says to the master, ‘Please, sir.’ And we all went.”

“Does Matvei live with you?”

“No, he’s got into a place.”

“With whom, though? The colonel?”

“With him, he offered 30 roubles, all expenses paid.”

“He didn’t get married, did Matvei?”

“He’s married, the same man gave him the money for the wedding, had a coat made for 80 roubles, but what about the wife? She lives in the countryside – is it allowed to live with a woman in a place like that? I’ve also thought about getting a place,” declared the speaker, having fallen quiet.

“How is Matvei, anyway?”

“A good gentleman, single, 30 roubles also, that’s how Matvei is.”

“You’ll be done for, Fyodor, just you see!”

“But maybe not.”

“And who is this gentleman, an acquaintance or what?”

“That one lives on Furstadtskaya, where Dmitri still serves in the junior ranks, on the first floor. He’s sometimes here as well, at Stepan Stepanovich’s.”

“An Old Believer, huh?”

“No way! He’s not even Russian, it seems. An Englishman, or something.”

“Is he well-regarded?”

“Yes, they say he’s a good, kind gentleman.”

“Well then, good day to you!”

“Farewell, uncle Yermolai, thank you for the food.”

“Drop by when you need to, Fedya.”

“I’ll come round,” and with a light step, clacking his heels, Fyodor went into the corridor, slamming the door. Vanya quickly went out and, without fully understanding why he did it, cried after the lad passing by in a jacket above a Russian shirt, out from under which hung the tassels of a thin corded belt, low patent leather boots and a peaked cap, cocked to one side, “Listen, you don’t happen to know how long Stepan Stepanovich Zasadin will be, do you?”

The latter man turned around and in the light penetrating from the numbered door, Vanya saw quick, thievish-looking grey eyes on a face, pale like those of people who live locked up or in a perpetual vapour, dark hair in a clip and a wonderfully defined mouth. Despite the somewhat coarse lines, there was some kind of spoiled nature in the face, and although Vanya looked on these thievish, tender eyes and shamelessly smirking mouth with prejudice, there was something in the face and the whole tall figure, the slimness of which struck the eye even while hidden beneath the jacket, that captivated him and led to a sense of confusion.

“And you would like to wait him?”

“Yes, it’s almost seven o’clock.”

“Half past six,” corrected Fyodor, taking out a pocket watch. “And here we thought that there was nobody in our room… He’ll probably be here soon,” he added, so as to say something.

“Yes. Thank you. Forgive me for bothering you,” said Vanya, not moving from his spot.

“Pardon me, sir,” responded the latter with a grimace.

A loud ring resounded and Stroop, Zasadin and a young, tall person in a long coat entered. Stroop took a quick look at Fyodor and Vanya, standing facing off against each other.

“I apologise for making you wait,” spoke he to Vanya at the same time that Fyodor threw himself to take off his coat.

Vanya saw all of this as though in a dream, feeling that he was falling into some abyss, and everything was clouding over with fog.

When Vanya entered the parlour, Anna Nikolaevna was finishing saying, “And it’s a shame, you know, that such a man is compromising himself like that.” Konstantin Vasilyevich silently shifted his eyes to Vanya, who was taking a book and sitting by the window, and said:

“They say ‘sophisticated, unnatural, excessive’, but if you restrict yourself to the uses of our bodies deemed natural, then all that’s left is to tear things apart with your hands and stuff raw meat into your mouth and fight with enemies; using your legs for chasing hares or running away from wolves and so on. It reminds me of a tale from The 1001 Nights, where a girl, tortured by the idea of finality, asks everyone what this or that was made for. And when she asks about a particular part of the body, her mother whips her, damning her: ‘Now you see what that was made for.’ Of course, this mum proved clearly the righteousness of her explanation, but that was hardly the limit of the capacity of the given place. All moral explanations of the naturalness of actions come back to the fact that the nose was made to be tinted with green dye. A person of full capabilities of body and soul must develop to the best of their abilities and search for the application of their abilities, if they don’t want to remain a Caliban.”

“Well now the students will get that into their heads…”

“’Well, this is in any case a positive and maybe it can be very pleasant,’ Larion Dmitriyevich would say,” and uncle Kostya, challenging Vanya, who did not stop reading.

“What does Larion Dmitriyevich have to do with it?” remarked even Anna Nikolaevna.

“Don’t you think it was his own view that I was putting forth?”

“I’ll go to Nata,” announced Anna Nikolaevna, rising.

“Ah, so she’s well? I haven’t seen her at all,” Vanya recalled for some reason.

“I’ll say, you’ve been disappearing for entire days.”

“Where have I been disappearing?”

“That’s for you to answer,” said the auntie, leaving the room.

Uncle Kostya drank down the remaining coffee and the room strongly smelt of mothballs.

“Were you talking about Stroop when I came in, uncle?” Vanya decided to ask.

“About Stroop? Truth be told, I don’t remember, it’s something Aneta was telling me.”

“I thought it was about him.”

“No, what would I have about him to talk about with her?”

“And you really suppose that Stroop is of such persuasions as you expressed?”

“That’s how he talks; I don’t know how he acts, and the persuasions of a different person are a dark and subtle thing.”

“So do you think his actions differ from his words?”

“I don’t know; I don’t know his affairs, and then it’s not always possible to act in accordance with your desires. For example, we were going to be at the dacha for a long time, and in the meantime…”

“You know, uncle, that Old Believer, Sorokin, invited me to his on the Volga: ‘Come,’ he said, ‘daddy won’t scold you; come see how we live, if that interests you.’ He proposed it to me so suddenly, I don’t know why.”

“Well, what of it, go set off.”

“Auntie won’t give me money, and it’s not worth it anyway.”

“Why isn’t it worth it?”

“It’s all so disgusting, so disgusting!”

“Hey, why has it all suddenly become disgusting?”

“I don’t really know,” said Vanya and he covered his face with his hands.

Konstantin Vasilyevich looked at Vanya’s bowed head and softly left the room.

There was no doorman, the doors to the staircase were open and a furious voice reached the hallway from a closed office, interspersed with silence, when some kind of quiet, seemingly female voice could vaguely be heard. Vanya stopped in the hallway without taking off his overcoat or cap. The handle of the door to the cabinet turned and someone’s hand, visible up to the shoulder dressed in a red Russian-style shirt, appeared, clutching the handle. Stroop’s words came through clearly:

“I will not allow someone to mention that, let alone a woman! I forbid you, you hear, forbid you to speak of this!”

The door closed again and the voices were dulled once again; Vanya took a wistful look around the hallway, so familiar: the electric light in from of the mirror and over the table, the clothing on the pegs; damask gloves were strewn over the table, but hats and upper-body clothing were nowhere to be seen. The door once again flew open with a crash and without noticing Vanya, Stroop went out into the corridor with a face white with fury; after a second, Fyodor followed after him almost running, in a red silk shirt, no belt and with a decanter in hand.

“How may I help you?” he turned to Vanya, evidently not recognising him. Fyodor’s face was feverishly red, like a drunkard’s, or as though rouged, his shirt was without belt, his hair was thoroughly combed and perhaps slightly crimped, and he smelt strongly of Stroop’s perfumes.

“How may I help you?” he repeated as Vanya stared him in the eye.

“Larion Dmitriyevich?”

“He’s not here, sir.”

“Then how did I see him just now?”

“Forgive me, he is very busy at the moment, sir, and there’s no way he can host you.”

“You will announce me, go.”

“No, really, it would be better to come back some other time: there’s no way it’s possible for him to host you at the moment. He’s not alone,” Fyodor lowered his voice.

“Fyodor!” called Stroop from the depths of the corridor, and Fyodor broke off to run down the corridor with a noiseless gait.

After standing around for a few minutes, Vanya went out onto the staircase, pulling closed the door behind which once again rang out the dulled, but still loud and furious voices. In the doorman’s room, her face in the mirror, stood a short woman in a grey-green dress and black knitted cardigan, correcting her veil. Approaching her from behind, Vanya saw clearly with a glance in the mirror that it was Nata. Having sorted her veil out, she unhurriedly went up the staircase and called to Stroop’s apartment, while in the meantime, the doorman had arrived just in time to let Vanya out onto the street.

“What’s this?” paused Aleksei Vasilyevich as he read the morning newspaper: “Mysterious suicide. Yesterday, the 21st of May, a young woman, full of hope and strength, Ida Golberg ended her own life in the apartment of an English subject, L.D. Stroop, on Furstadtskaya Street, building number —. The youthful self-murderer requested in her suicide note to not blame anyone for this death, but the conditions in which this grievous event took place push one to suppose a Romanesque undercurrent. According to the landlord of the apartment, in the midst of a heated discussion, the deceased wrote something on a scrap of paper, then quickly took Stroop’s revolver, which had been prepared for travel, and, before those present were able to intercede, emptied a round into her right temple. The solution to this mystery is complicated by the fact that Mr Stroop’s servant, Fyodor Vasilyevich Solovyov, of Orlovskaya Province, disappeared without a trace the same day, and that the identity of a lady who arrived at Stroop’s apartment half an hour before the fatal event remains unclear, as does the degree of her involvement in the tragic outcome. An investigation is in progress.”

Everyone around the tea table was silent, and all that could be heard in the room , awash with the odour of naphthalene, was the ticking of the clock.

“What on earth was that? Nata? Nata? Did you know about this?” said Vanya at last, with some voice not his own, but Nata continued tracing her fork around her empty plate, with not a single word in response.

[1] A poem by Lermontov

[2] A novel by Turgenev

[3] “…And saw that with a smile/They had been listening to these closing words/Then to the beautiful lady turned mine eyes” Dante, Purgatorio Canto XXVIII, tr. Longfellow (1867)

[4] A form of music notation without staves or notes used in the Russian Orthodox Church.

[5] Religious dissenter; look up Old Believers

[6] A type of Russian cabbage soup

[7] Quoting John Wortley’s 1992 translation, ““Look carefully, this is the fate of man, woman, and child. Enjoy your lust but remember: Your sin will deprive you of your place in the Kingdom of Heaven. How pathetic are the lives of humans! And you would forfeit the reward of all your struggles for just one hour of pleasure!”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria Nikolaevna on the balcony of the Lower Dacha, 1911.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The staircase of his apartment building was perfect for pre-run stretches. With Kolya clipped to the hand rail, Ivan set to stretching his knees, hamstings, and very, very gently his lower back and hips. The right side still wasn't as strong as it needed to be, but when pain started to disrupt his weight lifting, it was the final straw to embrace cardio.

His new living situation made it easier. A cheap high-rise with a parking deck was the perfect new home for a man and his dog, and the rental fees for his dacha was more than enough to pay for it. Storage was another thing, but the government recognized that some of the documents and pictures counted as "sensitive", so he had about four units full of rugs, pictures, trinkets, and any other bullshit he didn't feel like having broken. Even his old couch went into storage: he couldn't bear to part with it just yet.

But now, in the grey grid, he had all the freedom he could stomach between gym memberships, karaoke nights at bars, and running routes. An elastic leash let Kolya hit a stride alongside Ivan as they exited the building and took off towards the south.

While he ran, he usually listened to the news, but making phone calls was even easier than trying to find something upbeat. He rolled through the contacts on his phone and picked somebody he thought would be awake.

"Allo-allo?"

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

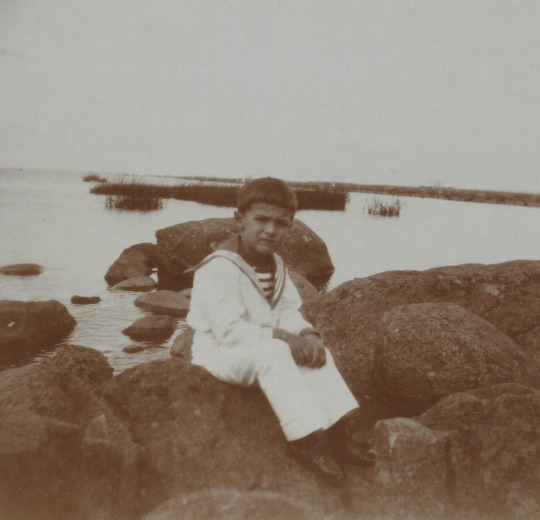

Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich being cute, Peterhof and Livadia 1910

#What a cutie 🥹🫶#my bby🤍#alexei nikolaevich#tsarevich alexei#1910#peterhof#the lower dacha#livadia#old livadia palace#alexei romanov

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria Nikolaevna and Anastasia Nikolaevna in Peterhof, 1909

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Update photo extra: Maybe 1905/06. Shows how the boat would arrive at the Lower Dacha at Peterhof to take the Imperial Family, often to Kronstadt, to board the Standart or, for shorter trips, the Marevo.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Olga Nikolaevna, Tatiana Nikolaevna, Marie Nikolaevna & Anastasia Nikolaevna at the Lower Dacha in Peterhof, summer 1904 OTMA

82 notes

·

View notes