#Ulfsild

Text

a portrait of history's unsung wizardly pioneer

mouse(@everybodyknows-everybodydies)'s writing on shalidor's much-overlooked ex-wife (and the mind behind half of his famed projects and discoveries) has captivated me utterly. nothing cooler than an old-timey woman whose contributions to her field were subsumed by her ex-husband and whose memory now exists only in buried glimpses and guesses, a series of scraps to be pieced fruitlessly together. my beloved

#ULFSILD!!!!!#considered giving her some kind of wolf jewellery but that felt a tad too self-referential yk#people don't generally wear jewellery about their names to my knowledge#so I gave her a beard ring with an owl pendant for jhunal instead :)#about time I drew a nord woman with a beard too. they deserve them#anyway LOOK AT MOUSE'S ULFSILD IDEAS. i like them#the elder scrolls#tesblr#skyrim#tes#my art#fay draws#ulfsild#nord

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

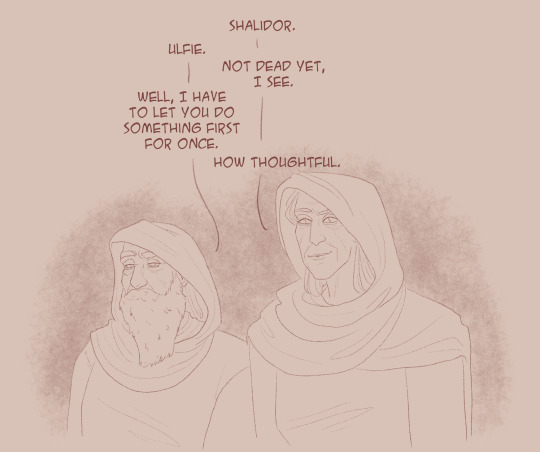

Shalidor. where's Eyevea.

#Elder Scrolls#Ulfsild#Shalidor#pictures taken moments before disaster#reverse-engineering what they would have looked like around this time. here's a silly doodle bc I'm having Ulfsild thoughts dklghsdklf

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

“So this is your College,” she says, without turning around. They haven’t spoken in—well, long enough to forget just how solid his presence feels, but not so long that she doesn’t recognize his step. He still stomps like a mammoth and drags his feet. Worse in the snow, always.

He comes to stand beside her, a professional distance from his shoulder to hers. “Impressed?”

It’s certainly meant to be impressive, at least—the stonework polished, gleaming; the towers academically tall. He’s had banners put up in too many places with a symbol she doesn’t doubt he designed himself. Waste of runework to shield that much delicate embroidery from the elements; they’ll be moved indoors well before Frostfall, she thinks to herself. “I noticed the statue.” He preens, the way his chest puffs out visible out the corner of her eye. Twitching a smirk, she says, “Funny you didn’t have it made of yourself, though.”

“Of course it’s—”

“Fellow they got to do it instead is obviously much too handsome.”

He splutters, tugs in irritation on one thick braid of his moustache. “You don’t have anything meaningful to say?”

“Hm.” She feigns deep contemplation. “What did you leave out of this one?”

“I didn’t leave anything out. If you’re here just to insult me, Ulfsild—”

“Someone’s got to remind you that you’re only a man while you’re signing your byline in titles, Archmage,” she says, light as the flakes freezing on her eyelashes. She breathes slow into her palms, curls the warmer air around her face to melt them again. Her fingers twinge. “And no one else seems particularly keen on doing the job. Kitchen?”

“It’s got a kitchen. You don’t like the title?”

“Makes you sound like a pompous ass, which is accurate, but I hadn’t thought you wanted everyone to know. Living quarters?”

“Don’t patronize me.”

“Library?” When he doesn’t answer, she barks a laugh, incredulous, and turns to look at him at last. He’s staring very pointedly at the central building and not at her. “Did you not put a goddamned library in your school, Shal?”

“There are plenty of shelves. Why would anyone borrow a book when they can just keep it for future reference—”

“You are going to kill me,” she says cheerfully. “I’ll laugh myself to death one day when you forget something important in your grand old quest to pluck down the stars. Watch, you’ll go to show off how easily you stride from here to Hammerfell in a single step, ready to revolutionize magical travel, and you’ll leave behind your own head because you didn’t think to cast down instead of up.”

“At least I’d have done it. More than some can say.” He’s silent for a moment, snow dusting his beard. If she didn’t know better, she’d think he’d oiled it just recently. He never did it this early in the week, though.

But. Well. Routines change just as well as people do, she supposes. She spells off the ache in her knuckles—comes back quicker than she’d like, these days—and shakes out her hands. Folds her arms and studies him. She needs to see his face for this part. “I read your piece on integrating runework during construction.”

He has the audacity to not so much as twitch a greying whisker at this. “Found it riveting enough to come discuss in person, did you? Nostalgic for old times?”

“I want my notes back.”

“You took,” he says evenly, “all your things already. Thirty years ago, you’ll recall.”

“You just happened, then, to remember exactly how I explicated the energy renewal process in layered stone—”

“Evidently, yes. Believe it or not, Ulfie, you do leave an impression.” His voice is dry. He flicks her an amused look, crosses his arms in perfect mirror of hers. “I’ll make a footnote in the reprint if it’s rankled you so much.”

“Footnote! You used my diagrams, Shal. From—” She shifts her jaw, finding it tight. She still spits sparks when she says the name, and the familiar static tingle in her teeth feels a warning. Instead, she takes a breath. “At least spell indeko right, you old fool. There’s no c.”

“What? Yes there is.”

“There’s not.”

“I’m not having this argument again.” He starts for the iron gate. “Come inside if you’re done and we can talk about anything else.”

She puts out a hand. He stops abruptly at the lock of the gate yanking into place with a horrible metal sound. “That’ll rust if you aren’t careful,” she says with a nod. “You really don’t ever learn, do you?”

He tips his head back, staring bleakly at the sky. “Let go of the gate.”

“Give me—whatever you kept. I told you I don’t want you using my notes. You put it at the wrong stage anyway, and I hope it was only in the paper and not in the construction here—though if you’re just going to give this one away to the first devil to dangle a promise in your face then maybe it doesn’t matter so much whether it stands or falls—”

“Let go of the gate,” he turns; “you’re going to break something.”

“Like you can’t put it together again,” she snaps.

“You know what I meant.”

Her hands are shaking. She doesn’t let go. “Swallow all the stars you want, Shalidor, but don’t pretend you’re here with the rest of us on the ground.”

“You don’t have to be on the ground. If you weren’t so damn myopic—” He cuts himself off, lifts a hand to sever her grip with a twist of his middle finger and his thumb, leaves her hands burning and claw-curled, rigid. The way he’s looking at her has her swallowing sparks again, running her tongue over her teeth. “Come inside. Stay here and do something great instead of theorizing yourself to death. Or at least let someone look at your hands. Is it worse?”

She huffs out a breath at a spasm in her palm. Stands up straighter. “You know we can’t work together.”

“You don’t even want to try?”

“No, Shal.” Shaking out her hands and tucking them into her sleeves, she closes her eyes for a moment. “I hope this one works out, I do. You don’t need me for that.”

He laughs. “No, I suppose you wouldn’t think so.” Gesturing to the gate, he says, “You’re welcome to search my rooms if you like. You won’t find anything in your hand, though, I promise.”

She doesn’t put much stock in his promises. Exhaustion presses at her shoulders: too much, again. She ought to go. Come back when she’s not dragging threads of magicka, fraying at every edge. But that would give him time to rearrange, so she shifts her jaw instead, makes her voice light. “Haven’t even seen the grounds and you’re inviting me up to your rooms.”

His eyebrows lift. “If you like.”

“Is the tall strapping statue model up there?” His face contorts—and despite herself, she feels her mouth pull into a grin.

#writing tag#Ulfsild#pops a bottle of champagne but it's actually just apple juice. WIZARD DIVORCE#not *necessarily* canonical but I liked exploring the dynamic here so. hands it to you#many many many years from now Kharish is in the courtyard staring at the statue like 'PLEASE explain about your ex-wife.'#she comes inside and tells Urag that didn't work bc the only thing that happened was she got the distinct impression the statue is wrong??

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

the inimitable and illustrious mage scholar Ulfsild. and her ex-husband

#Elder Scrolls#Ulfsild#Shalidor#Fanart#sketch#tensions high at the annual wizard convention as local bitterly divorced couple trade witty barbs#(LOVING this brush for doodling it is so A+)#scribble comic

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

*Marge Simpson voice* I just think they're neat!

#Elder Scrolls#Ulfsild#Shalidor#Fanart#gave her some wizardly sideburns here and you know what I'm into it I think it works#(playlist is closing in on an hour and I decided I probably needed a cover for it lol)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

where's that anime girl meme. Ulfsild mentioned 🎉🎉🎉

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

before and after the divorce. yes these are in the right order.

#Mouse talks!#I know with the first they're likely trying to gesture towards her disapproving of his magical pursuits but hear me out:#it's a crumb and I'm laminating it#magical academia arguments tearing this household APART#Ulfsild

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

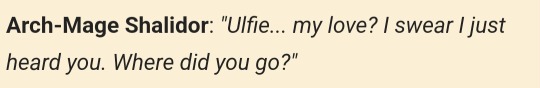

canon Ulfsild design which vexes me so. she's not even old... either they are implying Shalidor constructed and subsequently lost Eyevea both at a young age (hmm...) or she was significantly younger than him (hm.)

(or. they just threw in "default Nord woman" for this character who shows up exactly once as a memory ghost to go "you love your work... more than you love me......" and didn't put overmuch consideration into her design lol)

this design still reads as too young but I could be really into the idea everything went down when they were, like, late 30s early 40s maybe. she dumps him and then is off doing her own wizardly research and making discoveries in the field and every time she goes to publish something he's like "uhh that TOTALLY came from my notes I'm the one who came up with that actually" out of sheer pettiness. she publishes a follow-up that's just a long dissertation on everything he's gotten wrong in his last five Ye Olde Fantasy Academic Journal articles and includes a subtle dig about how one can only hope that his inattentiveness to the nuance of magical theorem means he's focusing on more mundane things, such as learning how to wash his own dishes finally. colleagues to lovers to bitter academic nemeses

#Mouse talks!#she's an icon she exists exclusively as a memory she doesn't even get a unique character design. and I love her#practicing age signifiers to give her a proper character design. I see you ma'am you can look just as wizardly as your ex-husband 🫡#Ulfsild

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ulfsild No-Last-Name you will always be legendary to ME. move over Shalidor I'm peeling off some of your legacy and giving it to your ex-wife as she deserves

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know logically there's other more reasonable explanations but it is infinitely funnier to me to take the fact that Shalidor lived and died in 1E and yet the Arcanaeum's collection only dates back as far as 2E + extrapolate that Shalidor just didn't think his magical institution of higher learning needed a library. they had to wait until he died and they were sure he wasn't coming back to start one. what do you MEAN both my students and my faculty might possibly ever need to look things up sometimes they can just ask me it'll be fine. anyway now back to that cool statue of me that's going in the courtyard,

8 notes

·

View notes

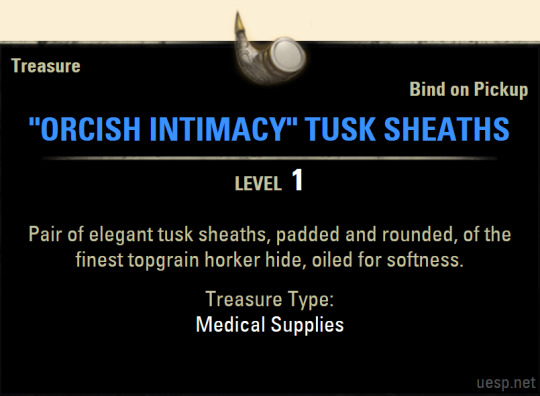

Text

anyway this "junk" item is the greatest thing ESO ever gave me and I'll stand by that

"medical supplies" they call these. staring into the camera with an expression of powerful Knowing.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The site had just been marked as a passing reference in one of the numerous incomplete texts in Shalidor’s own hand (not always legible, as the great mage—and she has very tactfully not said this aloud to Urag—had atrocious penmanship), which is why she hadn’t come expecting much the first time. Most of the places mentioned in Shalidor’s notes either no longer exist or are long since emptied, by age or by adventurers who don’t know anything about good conservation technique and insist on leaving their own journals all over the place with barely a page or two filled. She imagines whoever is bookbinding for these adventurers must run a surprisingly lucrative business.

This particular site, being potentially important (please let it be important), has earned a second visit after an impassioned dual presentation that the Archmage politely listened to about a nonsequential quarter of between extended bouts of contemplating the steam from his tea, should one be inclined to a generous estimate.

“This is it, then?” Tolfdir huffs out a breath and lowers his pack to the ground in a relatively dry patch, peering with interest at the mostly-buried structure before them. “I do so love a good excavation, it must be said. How did you get in the first time?”

“Well—” Kharish tests the dirt with the toe of her boot. Not too muddy, under the snow, as long as they’re careful. “Took some digging.” She drops into a crouch, tilts her head, squints. She’d covered up the entrance when she’d left last time to try to keep the interior as undisturbed as possible, not expecting to have to uncover it again herself. “Over there, I think—I couldn’t get to the door, but something knocked a hole in there that did drop down into what looked like the main entry passage.”

“Fascinating,” says Tolfdir, clapping his hands together. “Shall we?”

She goes first, because it’s more of a drop than she remembered and she does not want to know what happens to her career trajectory if he breaks an ankle. A smattering of dislodged dust and dirt dribbles from the lip of the hole in the ceiling when she looks up, arms held out and knees braced. “Rea—ack.” His satchel smacks into her temple and she blinks a brief burst of stars out of her eyes. He is unexpectedly sturdy. Maybe she could have let him go first after all.

“Thank you,” he says cheerfully, righting himself and starting down the dark hall, magelight already hovering over his shoulder. “They don’t put much padding on these floors, do they? Notes for future tomb-builders, let’s say.”

Kharish ducks under a low-hanging cobweb. “Future, er… I thought you said these kinds of tombs weren’t still being built?”

“Not at all,” Tolfdir pauses to inspect a relief, nose nearly against the stone. “But wouldn’t it be nice if they were? The use of a hall of the dead has been much more prevalent than a tomb barrow for—oh, ages now.” He seems pleased by whatever he needed to sniff from the wall and steps back again, brushing off his hands. “Eras, even! Why, I should tell you, it’s gone through several renovations of course, but the Windhelm hall of the dead, for example, is quite the historical treat. In fact, records dating back to the second era seem to indicate—”

She remembers abruptly that Urag specifically warned her, stressing the timeframe of once they’d arrived, not to ask Tolfdir about tombs. Or their architecture. You’ll never get him to stop, he’d said seriously, rubbing at the bridge of his nose the way he does when he’s been wearing his glasses too long, and you can’t afford distraction in there because we may not get another chance at this one. Do not let him talk about the tombs.

“What do you know about Ulfsild?” she interrupts—which is all she can think of right now, a little jittery, with the mental note to ask him again about the Windhelm hall of the dead on the way back to Winterhold to make up for the interruption—and hesitates a moment to slide an ajar coffin lid closed as gently as she can.

Tolfdir hums thoughtfully. She hadn’t expected it to work so well, but he says, “Oh, no more than the average scholar, I suppose. Not quite more than the name. It’s rather exciting, isn’t it? Another thing to love about these old places; every one holds some grand new discovery that could alter our understanding of the world as we know it.” He adjusts the strap of his satchel on his shoulder and continues, gesturing for her to take the lead now that he’s done studying the bas-relief. “It didn’t sound like you and Urag had gotten very far in the journal transcription; had you come across anything of note yet?”

It’s always better to be cautious about things that aren’t certain—if she were to allow herself to be a little reductive, she would say that history is nothing but context, and an asyndetic text, even a primary source, requires a degree of speculation that, applied too liberally, can often be worse than useless. And it’s not really quite her field anyway: she repairs the books. What’s inside, she’s still discovering, is often more questions than answers. “It’s a possibility,” Kharish acknowledges finally. There’s a narrow stairway; she turns sideways, awkward, to descend. “The back two-thirds looked much more esoteric, but the first section appeared to be fairly detailed notes on the construction of Eyevea. From what I saw of the relevant entries, her discussion suggested more of a—technical familiarity—than Urag says is typically believed she would have had.”

“I see! Yes, I believe I recall he told me their separation occurred during the whole Eyevea ordeal. Very sad, isn’t it?” he muses. “Scholars of the same discipline should never get too involved. Think how many good academic arguments would be discouraged if the participants risked upending their home lives!”

“Well, I don’t know about that; being able to articulate a distinction between your home life and your academic life should be a priority if you’re really invested in the preservation of both aspects of the relationship, but even so, incompatible personalities will probably always find something to—hang on, this one,” she cuts herself off, stopping before an arch marked with a stylized owl and going for her little notebook. The hollow eyes glare down at her. She squints back at them and then compares it to the unflattering scribble in her notes. “Yes. This one.”

“Ah!” Tolfdir peers up at it, redirecting his magelight to shift the shadows. A fistful of dust from overhead smatters into his hair. Kharish reaches up absently to ruffle the debris out of her own hair, waiting. The faint dust cloud that results drifts downward, glittering faintly in the magelight, and dissipates. “The owl of Jhunal—not as popular as Kyne’s hawk, as bird imagery goes, but no less significant for it. Did you know, when associated with a specific mage, the configuration of the feathers is thought to represent the school the mage specialized in—”

Scrambling for something to write with in her bag, she shakes her notebook to a fresh page. “Wait, wait, wait—really? Which feathers? What would this one represent?”

“Hmm,” he says, thoughtful. And then, again, “Hmm.” He puts a hand to his chin, gesturing with the other to move the magelight once more. “I can’t say it looks to be one of the established schools of magic. The barring on the tail is quite destruction, but the chiselwork across the shoulders more closely resembles the iconography for alteration. And the head! Difficult to make out, but it doesn’t look right at all. You know, I do wish we’d thought to bring a stepping-stool.”

She pauses, staring at the owl. If it were a flat carving they could take a rubbing and look at it later in better light, perhaps; beveled as it is though, the distortion of a rubbing might obscure or alter some small important detail. “Can you draw?”

“Oh, well,” says Tolfdir, stroking his beard modestly, “I won’t be asked to paint in Solitude any time soon, certainly, but I have been known to—doodle, as it were. On occasion. One must have hobbies, after all.”

---

Which is how he ends up on her shoulders, carefully copying the owl into her notes.

“The iconography really is all over the place,” he muses. “It will be worth reviewing my references once we get back, I believe. Most fascinating!”

“I’m sure it’ll be a—” He can’t see her, but she valiantly struggles to maintain a straight face anyway, on principle. “—hoot.”

The scrtch of paper pauses overhead as he laughs, sudden and delighted. “Yes, of course! I’ll be certain to gather, ah, owl the material required.”

“Ha! —whoops, sorry—” The laugh pitches him backwards with an oop!; she bites back her grin, standing straighter and rebalancing him. “If all else fails we may have to wing it.”

“Oh, no,” he says gravely, “that would be academically irresponsible.” When she sets him down, though, there’s a twinkle in his eye as he returns her notes. “Here you are: one mysterious owl, rendered to the best of these old hands’ capabilities. Onward, then,” he begins, looking preemptively pleased with himself; “while we still have a few unruffled feathers each.”

Her laughter rings out with an echo down the hall ahead of them. The dust that falls loose from the ceiling lands light as snow.

---

The room is just as she left it, mostly: the loose jaw of the skeleton in the sarcophagus at the center of the room has dropped to tangle with the collarbones. “Sorry,” Kharish whispers to the skull, gingerly lifting the mandible pieces back into place, pressing a touch of sticking shield to the joint with her thumb. It will almost certainly fall apart again, but not, at least, while they’re here. To Tolfdir, she says aloud, “There shouldn’t be anything new—I took the journal from the mouth, three pieces in worse shape from the shelf, and a rubbing of the inscription at the base of the platform.”

He has his nose poked rapturously into an urn when she turns around. “Funerary oils,” he says by way of explanation; “they vary slightly depending on region, era, belief—” A beat. He sniffs it again. “Decidedly floral,” he says, thoughtful. “Though gone quite stale, of course.”

There isn’t anything new, as predicted. She generally leaves the grave goods alone. No need to bother with anything that can’t be read or transcribed or translated. The dead should be allowed to keep whatever artefacts of life they have left, when they can; the ones that have opinions on the matter historically tend to agree on this. Much of what’s here, Kharish thinks, seems puzzlingly unimportant, as far as things left in tombs go. A cracked alchemical retort, bits of glass around the base, next to three also-smashed empty bottles. A plain, tarnished metal ring at the bottom of half a mug. A regular, if rotten, stick that (she checked) has no magical resonance whatsoever.

Checking through the shelves up against the wall for anything of interest, she pauses at a small metal figure of a wolf, on its side behind a cup and laid atop a disintegrating scarf. Cruder than an artisan’s rendition would be, with the tell-tale prick about it of something that’s been shaped with magic. The back of the head and the base of its ears have been worn smooth, as though by the meditative rubbing of a fingertip. Careful, she takes the wolf—small and disconcertingly cool in her palm. For Mara or for Ulfsild herself, she wonders. She can’t say it in any official capacity, as it’s a sentimental and unacademic thought, but it’s cute. And the soft shape of the ears and the tilt of the head do seem to invite touch.

No maker’s mark on it, though. Made then by someone who didn’t make a habit of magic metalworking? She sets the wolf upright on the scarf again, the clink of little inexpertly-shaped metal paws on the shelf muffled. It’s the only thing like itself in the room. Broken glass, broken dishes, dried-out inkpots, a rotting scarf, and a wolf. And lots of dust and dirt, but that’s a given.

Too many questions, really. She wipes her palms on her thighs and turns back to the center of the room. “What do you make of the epitaph?”

“A bit more hostile than epitaphs tend to be, curiously.” Tolfdir sets down a lens he’d been inspecting and nods back to the sarcophagus, peering at the plaque again. He threads his fingers through his beard in contemplation. “It’s rather—well, the person leaving the inscription clearly wishes regret upon the, ah, entombed, expressing triumph at outliving her, with some rather colorful language and a consumptive metaphor; though I’m not quite clear why.”

“A consumptive—oh,” she says; then, again, “oh.” The notes left pointedly wedged between the teeth. Hand to her mouth, she looks from him to the empty eye sockets of the skull. “—eat your words.”

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

idk what everyone is talking about I think that the tumblr search is very functional. for example I searched "Shalidor" on my blog and it pulled up my Ulfsild tag instead. oh how the turntables

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

13 for kharish <3

13: too loud

“—in the third, heavily warded—wait,” she says, nearly reaching her usual volume with alarm as she throws an arm out across the desk.

Urag stops, looking skeptically over his glasses at her. “What?”

Mug in her other hand halfway to her mouth, Kharish waves a hand over the book he was about to pick up. “Don’t touch that one bare-handed,” she croaks, and takes a long drink rather than explaining why.

He takes the pause to study it visually instead. Heavily warded as it might have been to start with, she’s done a number wrapping it back up for transport—he counts seven distinct layers of shielding. The magicka signature underneath is faint, but identifiable; even without the Jhunal owl stamped in the corner, he could have recognized the spell-traces they’ve found on the three Ulfsild texts besides the first.

She sets down the tea. It doesn’t seem to have done much, as she’s still hoarse and scratchy when she says, “It yells.”

“It… yells.”

“At you. If you touch it. Especially if you try to open it.”

“Hm. And did you yell back at it, or—”

“It uses your voice,” she says miserably. “I couldn’t get whatever’s laid on it undone while it was—er, while it was going.”

Could be a handy trick to know, he thinks, if they can work out how to replicate it after they’ve picked it apart to let them see the book itself. Place it on the door to the restricted section and it would be much easier to listen for anyone in a sharp black uniform who thinks they don’t need special permission from both himself and the Archmage, despite the clear signage in multiple places.

Just for example.

Urag nods, smoothing out the page he’s taking notes on. “I’ll have to see it engaged before I can look for how to dismantle it.”

She grimaces. The shielding layers peel off one by one; the book almost shivers, and when she touches the edge of the cover it unleashes an ear-splitting scream that has them both jumping half out of the chairs.

“Right,” he says, heart having lurched solidly into his throat, as she jerks her hand back on reflex. There’s a jagged black line of ink across his notes that wasn’t there before, his pen tip snapped off—he takes a rag to it and clears his throat. “Well, now that our blood pressure’s up.”

“Ha,” she wheezes, and tries again.

“Oh, look at me,” bellows the book in a concerningly accurate facsimile of Kharish’s voice (notably, not hoarse) as soon as her fingertips meet the leather binding; “I can’t remember whether I’m meant to lead with the left or the right when I start a circular rune, I have to check someone else’s notes because I can’t organize my own—”

The inkpot at the other end of the desk rattles right off the side. He leans to catch it—misses—with a crack it lands on the floor and sweeps a perfect arc of ink across the stone tile.

For a moment it is deathly silent. He rights himself in his chair with the grim deliberation of a glacier. Kharish, both hands pulled back to herself, says with a pained expression, “I don’t really sound like that all the time, do I?”

Urag gingerly wraps her scarf back around the book to pick it up. Despite the physical barrier, there’s a tingle in the back of his throat when he does. “…on second thought, let’s take it outside.”

#writing tag#Kharish gra-Shatul#THANK YOU... <3#magic librarian hazard number ???: getting your voice stolen by one of those talking password diaries. whoops!

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Why,” says her mentor with a kind of exasperated patience she is not ashamed to say she’s missed, “are there dental impressions in the leather binding.”

Kharish discreetly swipes some blood from her upper lip and nods. “They’re not mine,” she says, as preface, which is unnecessary; the altitude adjustment always leaves her a little lightheaded for a day or two. “The interred corpse had the text placed in its mouth. It was unclear for what purpose.” She swipes at her mouth again. The split lip had been healing just fine on the journey back to the college—it’s the dry cold, she thinks, that’s cracked it open again. “It did not… reanimate. Upon removal.”

“Nords,” grumbles Urag, and peers down at the delicate book on the table between them, careful not to obscure the light. “Nice technique with the shielding.” He unfolds the wire frame of a pair of glasses and puts them on, gingerly opening the cover of the book. It’s coming loose from the spine, the alteration magic woven around it the only thing keeping it from falling apart. The pages are translucent-thin, the ink of the spidery scrawl faded to a pale amber.

She’s holding her breath. Probably not helping the lightheadedness. She attempts the subtlest of exhales and tastes more blood on her lip. “Initial examination suggested this was not Shalidor’s, but an assistant’s, concerning the construction of Eyevea.”

He twitches an eyebrow. “I would disagree.”

“The handwriting—”

“It’s not Shalidor’s,” Urag says, “but it’s not an assistant’s, either.” He uses the thin tip of a dry, narrow quill to indicate an inscription in the corner of the leather interior, careful not to touch. “Ulfsild.”

She waits. The name is unfamiliar; if not an assistant, she isn’t aware of any other colleagues the original archmage might have allowed to take notes on his studies, especially of such a sensitive topic.

“Did you happen to notice reference to the author’s husband?” There’s a tinge of excitement to his voice.

“Erm,” Kharish says eloquently. “I… am unclear how the author’s relations relate to—”

“Ulfsild,” Urag cuts her off, setting the quill down and sweeping his glasses off to rub at the lenses with the end of his robes, “was Shalidor’s wife.”

Her eyes go wide. “No,” she says. And then, dragging her hands down her face to cover her mouth, “No.”

“The few records that mention her indicate that she did leave him,” he concedes, “so perhaps ex-wife is the more appropriate term, I suppose.”

Muffled by her hands, she says, “Then was the body—? That is—was that her?”

“It’s a possibility.” He turns to the second page with professional delicacy. “I’ll transcribe the text so we can study it without risking damage to the original. Regardless, we’ll let the archmage know; if Arniel can get permission to send unvetted mercenaries stomping through Dwemer ruins, the least Aren can do is let us send someone qualified to study the location. Maybe I’ll go myself. Ulfsild is something of a contested figure, as there’s so little known about her; her actual contributions to the study of magic—if any, we don’t even know for certain if she was a mage—were almost undoubtedly absorbed into the body of Shalidor’s work and credited to him. This could be quite revelatory. Most likely there won’t be much in the way of textiles left, but there’s plenty beyond…” He trails off, then squints at her. “What?”

She shuts her eyes. “The book,” she says. “It was… stuck.”

“It was stuck,” he repeats.

“In the mouth. Of the body.”

“Right. Hence the dental impressions.”

“I broke the jaw off,” she says.

Urag stares at her.

“It was very stuck.”

Slowly, he puts his head in his hands, elbows on the table. “You broke off the jaw,” he says, “of the wife of Archmage Shalidor, founder of the College of Winterhold, one of the greatest mages in history—”

“Ex-wife, you said,” she supplies, a little desperate, “and it could be—someone else!”

“It’s fine.” He does not look up, sounding as though convincing himself more than her. “It’s fine. Jaws can be reattached. —was it stuck because of a spell?”

“No! There was no magical signature, and I didn’t—I put it back.”

“You put—the jaw?”

Embarrassed, she says, “Well, it was a person. At one point. I didn’t want to be rude about it.” And an important one, evidently. Her palms are sweating. “There weren’t any other salvageable texts. I looked. I looked.”

“I know. I trust you would have.” He gets up, rubbing at the bridge of his nose. “Alright. Things happen to corpses all the time. Ask Phinis, they’re not made to stay together anyway.” Urag gestures to the book. “Still, it’ll be worth going over, with a find like this. Imagine.” He laughs, suddenly, and tugs a handkerchief from his pocket to offer. “You’ve got a split lip. Good job with this one.”

She takes the handkerchief and finds herself slowly mirroring his wide smile. Good job. Maybe he’s right. Maybe the archmage really will fund an expedition.

Whatever else happens, she thinks, holding the handkerchief to her mouth, this has got to be the most significant thing they’ll find all year.

#writing tag#Kharish gra-Shatul#have been doing little bite-size pieces like this while I hammer ever slower at my longfic.#allowing myself freedom from context!!

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

(likely nonexhaustive) list of places Shalidor constructed

Eyevea: traded it away for a book that was supposed to be full of secrets to broaden the mind. regretted this apparently very soon after. the place itself upon return in ESO (2E) looks relatively fine as in it's still largely intact, but also, most of the activity is happening outdoors because the buildings that do exist are so small. "haven for mages" cool great but where does anyone sleep. has multiple statues that appear to possibly be highly flattering depictions of himself however (recurring theme)

Ice Fortress: I am so serious about this. he made himself an Elsa castle. appears to have been full of riddles. why did he do this. obviously this place is LONG gone, probably because it was, again, made out of ice. UESP suggests he and Ulfsild both lived here but I would instead like to propose he made this completely impractical but thoroughly flashy "home" in a fit of pique very soon post-divorce. quoth Ulfsild, from her normal person house that can be heated without the entire thing melting and causing an avalanche: "lol."

Winterhold + the College: gestures with immense sorrow to the Great Collapse. lasted a long time until then at least!! "wizards caused the Collapse" first of all no. second of all if you're very insistent on this being the case we could hypothesize that maybe ONE did given his previous track record with construction... not those ones though they're doing the best they can with what they have :(

Labyrinthian: wizard death maze built on top of an important dragon cult city. may have been blissfully unaware of the actual dragon priest stuck there for who knows how long. "all of this will have no negative consequences whatsoever," confidently declares greatest mage in the history of the world. the maze has a body count

#Mouse talks!#this is a post made with great affection. love a man who never learns from his mistakes and instead thinks the solution#is to be more and more ambitious until his desire to become a legend outstrips his common sense#it's just funny honestly!!#Shalidor

2 notes

·

View notes