#accessibility tools that are inherently ableist in design

Text

Edit: the app launched and Is down- I have the initial apology video in a post here and I’m working on getting a full archive of their TikTok up ASAP. I’m letting the rest of this post remain since I do still stand by most of it and also don’t like altering things already in circulation.

Warning for criticism and what I’d consider some harsh to outright mean words:

So I’ve just been made aware of the project known of as ‘lore.fm’ and I’m not a fan for multiple reasons. For one this ‘accessibility’ tool complicates the process of essentially just using a screen reader (something native to all I phones specifically because this is a proposed IOS app) in utterly needless and inaccessible ways. From what I have been seeing on Reddit they have been shielding themselves (or fans of the project have been defending them) with this claim of being an accessibility tool as well to which is infuriating for so many reasons.

I plan to make a longer post explaining why this is a terrible idea later but I’ll keep it short for tonight with my main three criticisms and a few extras:

1. Your service requires people to copy a url for a fic then open your app then paste it into your app and click a button then wait for your audio to be prepared to use. This is needlessly complicating a process that exists on IOS already and can be done IN BROWSER using an overlay that you can fully control the placement of.

2. This is potentially killing your own fandom if it catches on with the proposed target market of xreader smut enjoyers because of only needing the link as mentioned above. You don’t have to open a fic to get a link this the author may potentially not even get any hits much less any other feedback. At least when you download a pdf you leave a hit: the download button is on the page with the fic for a reason. Fandom is a self sustaining eco system and many authors get discouraged and post less/even stop writing all together if they get low interaction.

3. Maybe we shouldn’t put something marketed as turning smut fanfic into audio books on the IOS App Store right now. Maybe with KOSA that’s a bad idea? Just maybe? Sarcasm aside we could see fan fiction be under even more legal threat if minors use this to listen to the content we know they all consume via sites like ao3 (even if we ask them not to) and are caught with it. Auditory content has historically been considered much more obscene/inappropriate than written content: this is a recipe for a disaster and more internet regulations we are trying to avoid.

I also have many issues with the fact that this is obviously redistributing fanfiction (thus violating the copyright we hold over our words and our plots) and removing control the author should have over their content and digital footprint. Then there is the fact that even though the creator on TikTok SAYS you can email to have your fic ‘excluded’ based on the way the demo works (pasting a link) I’m gonna assume that’s just to cover her ass/is utter bullshit. I know that’s harsh but if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck it’s probably a duck.

I am all for women in stem- I’ve BEEN a woman in Stem- but this is not a cool girl boss moment. This is someone naive enough to think this will go over well at best or many other things (security risks especially) at worst.

In conclusion for tonight: I hope this person is a troll but there is enough hype and enough paid for web domains that I don’t think that’s the case. There are a litany of reasons every fanfic reader and writer should be against something like this existing and I’ll outline them all in several other posts later.

Do not email their opt out email address there is no saying what is actually happening with that data and it is simply not worth the risks it could bring up. I hate treating seemingly well meaning people like potential cyber criminals but I’ve seen enough shit by now that it’s better to be safe than sorry. You’re much safer just locking all your fics to account only. I haven’t yet but I may in the future if that is the only option.

If anyone wants a screen reader tutorial and a walk through of my free favorites as well as the native IOS screen reader I can post that later as well. Sorry for the heavy content I know it’s not my normal fare.

#it’s especially insulting the way this is marketed as solving a problem when the solution already exists#ableism#lore.fm#terrible app ideas that shouldn’t happen#serious#accessibility#screen readers#lore.fm should not launch#accessibility tools that are inherently ableist in design#I wish I was making this up

588 notes

·

View notes

Text

Universal Design and the Problem of “Post-Disability” Ideology - Part 1

Hamraie, A. (2016). Universal Design and the Problem of “Post-Disability” Ideology. In Design and Culture (pp. 285-309). https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2016.1218714

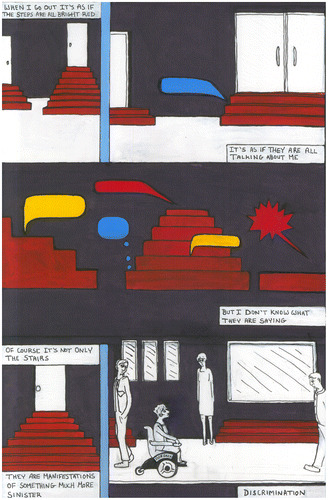

"Disabled artist Sunaura Taylor’s Thinking Stairs (Figure 1) depicts a gray-scale sidewalk flanked by cartoonish red staircases emitting empty speech bubbles. The landscape appears disembodied, impartial, until the final frame, in which Taylor herself appears as a black and white figure driving her powerchair amid staring pedestrians. Wordlessly, the stairs communicate what the people – and their stares – do not: Taylor is out of place. This world was not built with her in mind."

"Twenty-six years after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990, discriminatory features endure in built environments, and accessible design remains marginal within mainstream design practice and theory. Indeed, design scholars and practitioners rarely recognize disability narratives, such as Taylor’s, as valuable sources of architectural and design critique. The discourse of Universal Design, however, gains popularity in design criticism, journalism, and scholarship as a common sense strategy for making built environments more usable for all people.1 While few would object to the promise of a more usable world for everyone, I argue that the portrayal of Universal Design as simply a form of neutral, common sense “good design” (and not design that ensures accessibility for disabled users) distances this approach from the civil rights mandates of the ADA and, by extension, from the notion of disability itself."

Critical Disability Theory

"The field of Disability Studies coalesced in the 1980s around the “social model of disability,” which critiqued medical and rehabilitation models of disability (Oliver 1990, 22; Union of Physically Impaired Against Segregation 1972, n.p). According to the social model, disability is an experience of discrimination resulting from inaccessible built environments, rather than an inherent pathology or impairment in the body. More recent critical disability theories, however, argue that the social model’s sole focus on the functionality of built environments does not go far enough to challenge the cultural logics of ableism. Ableism, or the “ideology of ability,” dictates that life without disability is preferable to life with disability (Siebers 2008, 8). When societies frame disability as deviation from dominant norms and therefore “a problem to be eradicated,” critical disability theorist Alison Kafer (2013, 8–10) explains, “ableist understandings of disability” appear as “common sense,” while the notion of preserving or even desiring disability appears as pathological or unthinkable. Disability has thus become a “master trope of human disqualification,” a concept whose presence is treated as a de facto problem to eliminate (Mitchell and Snyder 2006, 125).

Critical disability theorists emphasize instead that the design of “habitable worlds” must involve treating disability itself as a valuable way of being in the world, one that societies must work to accept and preserve rather than cure or rehabilitate (Garland-Thomson 2014, 300). A habitable world, in other words, would offer more inclusive ideological assumptions about disability, and not simply more accessible structures. Attention to cultural representations of disability has been largely missing from Universal Design discourse, however. Proponents often treat Universal Design as a de facto good, untouched by broader social and political forces, and neutral toward disability. Critical disability theory, by contrast, offers historical and theoretical tools for examining the persistence of ableism in contemporary Universal Design discourses."

Design and Disability in the Pre-ADA Era

"Debates about Universal Design’s relationship to disability often treat accessible design as a stable, ahistorical phenomenon. This presumed stability enables advocates to frame Universal Design as an objective example of “good design” and accessible design as a manifestation of “bad design.” Design historian Stephen Hayward (1998, 222) argues, however, that since its emergence in the 1930s, the representation of “good design” as “common sense” has been an “exercise of power, concomitant with a hegemonic idea of progress or modernity, and the antithesis to a contrary world of ‘bad’ or ‘uncultivated’ design.” Accordingly, understanding Universal Design’s seemingly neutral claim to be “good design” requires a more critical engagement with issues of history, power, and privilege surrounding the concept of disability. When informed by critical disability scholarship, this kind of engagement can also help distinguish the intentions underlying Universal Design discourses and the consequences of these discourses for disability inclusion or exclusion."

Eliminating Disability

"In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, design, medicine, and state power converged around the project of eliminating disability. Thousands of people with supposed cognitive and physical defects (presumed to be excessively dependent or incapable of becoming productive citizens) were incarcerated or sterilized in US institutions; these spaces subsequently provided templates for Nazi eugenics programs (Chapman, Carey, and Ben-Moshe 2014, 6–7; Friedlander 2000, 7–9; Johnson 2003; Mitchell and Snyder 2006).3 Together, eugenics and institutionalization separated disability from public life, rendering the presence of disabled bodies in public space unthinkable and reinforcing the association between disability and disqualification. When treated as common sense, the violence of eliminating disability appeared instead as a “humanistic solution to a social crisis” (Mitchell and Snyder 2003, 85).

Disability historians have shown that this imperative to eliminate disability – to imagine what I am calling a “post-disability” future, in which disability no longer poses a “problem” – extended to standards of “good design.” Eugenicists defined “degeneracy” and “feeblemindedness” (often described as a lack of common sense and intelligence) by measuring an individual’s ability to cope with the design of urban settings (Mitchell and Snyder 2003, 84–85). So-called “ugly laws” prohibited people with atypical bodily features from inhabiting public places. These laws, Susan Schweik (2009, 5) argues, targeted the figure of the “unsightly beggar,” a figure often imagined as a disabled panhandler, but revealed a broader ideological investment in individualism, “which enabled the law’s supporters to position disability and begging as individual problems rather than relating them to broader societal problems,” such as economic and racial inequities. Industrial designers in the 1930s, according to Christina Cogdell (2010), drew upon eugenic goals of culling disabled, non-white, and poor people from the human stock to inform their elimination of aesthetic and functional excesses from “streamlined” consumer products. Twentieth-century architectural handbooks adopted human statistics (derived from military and eugenics research) as standards for the typical inhabitant of architectural structures, and thus reinforced norms of race, gender, and ability (Hamraie 2012; Hosey 2001, 103). When defined by a preference for able-bodied users, “good design” relied upon what Rosemarie Garland-Thomson (2012, 340–341) calls the “eugenic logic” of disability elimination. It easily reinforced the ideology of ability by presenting inaccessible built environments (and the subsequent exclusion of disabled users) as part of the natural order of things, as common sense and untouched by power.

The accessible design movement in the United States (known as “barrier-free design” beginning in the 1960s) emerged through early and mid-twentieth-century efforts to include disabled citizens in public life (Fleischer and Zames 2011, 36–37; Penner 2013, 215–217). Early accessibility sought to expose the norms of embodiment around which architecture and design cohered. However, early advocates focused on troubling the exclusion of disability from standards of normalcy rather than challenging the imperative for normalization itself. In the post-World War II era, accessible design quickly became entangled with economic, medical, and military imperatives to create productive bodies and healthy citizens.5 The return of injured soldiers from war renewed efforts at normalizing bodily function through medical and vocational rehabilitation, rather than through the social acceptance of atypical embodiments (Serlin 2004, 12). Rehabilitation experts and scientific managers such as Edna Yost and Lillian Gilbreth (1944) and Howard Rusk and Eugene Taylor (1949), and industrial designers such as Alexander Kira (1960) believed that when fitted with the correct tools, amputees, paraplegics, and other disabled veterans could become productive workers and citizens (Williamson 2012b, 215). Accessibility advocates argued that inclusive built environments with features such as wheelchair ramps, folding shower seats, elevators, grab bars, and wide doorways would grant disabled people access to public life, employment, education, and housing (Nugent 1960; Rehabilitation Services Administration 1967). Given the right equipment and appropriate built environment, injured soldiers could work in factories, drive automobiles, and realize the American Dream. Disabled people, in other words, could become normal by design (Serlin 2004, 27).

Rehabilitation experts, rather than designers and architects, produced the first accessibility standards in the US. At the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana in the late 1950s, researchers such as Timothy Nugent enlisted disabled students (often veterans attending university through funding from the GI Bill) for research on features such as ramps (Fleischer and Zames 2011, 36; Pelka 2012, 94–112). Thereafter, Nugent (1960, 53) wrote that rehabilitation professionals “are finding it very difficult to project clients into normal situations of education, recreation, and employment because of architectural barriers,” adding that “solution of these problems is not within the realm of professional rehabilitation workers but must be accomplished by … the architects, engineers, designers, builders, manufacturers, and in all probability, the legislators, with encouragement and guidance from those professionally engaged in rehabilitation.” Rehabilitation concepts and data were thus brought to bear on architecture and design practices, similar to the influence of ergonomics and human factors data on the field of industrial design through the work of Henry Dreyfuss (1960).

Though rehabilitation professionals were not architects, their evolving theories of disability involved the interactions between individuals and built environments. A key rehabilitation concept was the notion of “functional limitation,” or the environment’s effect on a person’s ability to engage in life activities such as eating, cleaning, or working (Hahn 2002, 162–189; Institute of Medicine 1997, 148). According to an influential model proposed by medical sociologist Saad Nagi in 1965, functional limitation was situational and distinguished from the categories of “pathology” and “impairment,” which presumed defects inherent to individual bodies (Nagi 1991, 309–327).6 The shift to understanding functional limitation as distinct from pathology or impairment appeared progressive in the sense of rejecting medical and curative approaches to disability. Nevertheless, it followed from the functional limitation concept that disability was a problem to eliminate, and the concept thus maintained an attachment to what Robert McRuer (2006, 2) calls “compulsory able-bodiedness.” Accessibility practices premised upon functional limitation likewise positioned architects, industrial designers, and engineers (rather than physicians) as experts with the tools to correct perceived limitations in a user’s performance in the name of productivity, thereby reinforcing ideologies of ability (Williamson 2012b, 216).

Preserving Disability

Concurrent to the rise of barrier-free design, disabled people responded to rehabilitation and eugenic logics of elimination with demands for acceptance and preservation. Beginning in the 1960s, disability communities responded to institutionalization by forming mutual aid networks, sharing knowledge, and crafting strategies to survive in existing built and social environments (Williamson 2012a, 8). Deaf and hard-of-hearing people formed culture around the shared use of American Sign Language (ASL) (Van Cleve and Crouch 1989). While targeted by eugenicists and often forced into schools that emphasized lip reading and spoken communication, deaf people formed activist networks to reject assimilation and emphasize the unique cultural, spatial, and ethical orientation of ASL communication (Silvers 1998, 71).7 In communities of people with mobility impairments, wheelchairs and crutches became aesthetic and functional tools for dance and sports (Lifchez and Winslow 1982, 154–155). Self-taught design practices were often central to disability cultures. As Bess Williamson (2012a) has shown, people with post-polio disabilities and their families, for whom the mainstream of “good design” was not accessible, shared tips for tinkering with assistive devices, wheelchair ramps, and automobiles through newsletters and social networks. The disability culture that emerged from these efforts offered a view of disability as culturally vibrant and politically resourceful. Disability culture embraced a “counter-eugenic logic,” according to which societies should embrace, rather than eliminate, disabled people’s unique ways of relating to and engaging with one another (Garland-Thomson 2012, 341). When disabled people created culture and community, they challenged the association of disability with tragedy, pain, and decreased quality of life.

Disability activists of the 1960s and 70s imagined a future centered on the needs and expertise of disabled people, rather than compulsory rehabilitation and normalization. The Independent Living movement, for instance, positioned disabled people as experts about their own experiences, worked to liberate disabled people from institutions and nursing homes, emphasized mutual aid, and promoted the value of interdependence (Pelka 2012, 113–130; “The University Picture” 1962). Unlike rehabilitation experts who sought accessibility as a tool for normalization, and unlike mainstream architects and designers who understood accessibility as antithetical to creative and aesthetic choices, disability activists claimed their expertise as users of built environments to justify their authority to redefine “good design.” Architects Raymond Lifchez and Barbara Winslow capture this emerging disability design philosophy in their landmark Design for Independent Living, which catalogues the accessible design efforts of the Independent Living movement in Berkeley, California. They write:

"Is the objective to assimilate the disabled person into the environment, or is it to accommodate the environment to the person? … Currently, the emphasis [in barrier-free design] is on assimilation, for this seems to assure that the disabled person, once ‘broken-in,’ will be able to operate in a society as a ‘regular person’ and that the environment will not undermine his natural agenda to ‘improve’ himself. … [T]his assumption can be counterproductive when designing for accessibility. It may serve only to obscure the fact that the disabled person may have a point of view about the design that challenges what the designers would consider good design. Many designers have, in fact, expressed a certain fear that pressure to accommodate disabled people will jeopardize good design and weaken the design vocabulary. Though certain aspects of the contemporary design vocabulary may have to be reconsidered in making accessible environments, one must also look forward to new items in the vocabulary that will develop in response to these human needs – ultimately leading toward more humane concepts of what makes for good design. (Lifchez and Winslow 1982, 150)"

In other words, activists redefined “good design” as accessibility and social inclusion for all disabled people, regardless of their productivity or conformity to dominant standards of citizenship. This position built upon the social model of disability, which defined the social exclusion of disability as environmentally produced, rather than a common sense or natural occurrence resulting from flaws in individual bodies.8 The key difference between the social model and the “functional limitation” model, however, was the new emphasis on disability as a cultural resource that should be valued and preserved through accessible built environments.

Several practical and conceptual concerns limited the success of accessible design in the 1970s and 1980s. Despite the passage of laws such as the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 and Section 504 of the Federal Rehabilitation Act, enforcement remained limited or non-existent (Jeffers 1977). When these laws were enforced as a result of high-profile activist protests and sit-ins, their enforcement mechanisms – standardized codes and checklists – prioritized the needs of specific disabled people – particularly wheelchair users – who had been subjects of rehabilitation research. This was evident in the way that wheelchair users became emblematic of the broader disability community with the adoption of the “International Symbol of Access” on accessible parking placards and other signage (Ben-Moshe and Powell 2007, 500; Guffey 2015, 359–360). More expansive guidelines would be necessary to facilitate inclusion for people with other (or additional) physical, sensory, or cognitive disabilities. Finally, accessibility standards reduced disability to functional limitations that could be addressed through checklists solutions such as ramps of a certain slope or doorways of a certain width. They did not, however, promote a cultural or disability rights model that would emphasize qualitative dimensions of meaningful accessibility or creative design beyond minimal standards (Mace 1977, 160–161). These specific concerns involving bureaucratic codes, standards, and legal compliance approaches to accessibility culminated in a new discourse: Universal Design.

Foregrounding Disability

Universal Design emerged from the work of disabled designers who lived through the struggles over enforcing accessibility codes in the civil rights era. Ronald Mace, a disabled architect and wheelchair user, had direct experience with long-term hospitalization, exclusion from schools, and employment discrimination.9 In the late 1970s, he became involved with efforts to write new accessibility codes and educate architects and designers about best practices, but these experiences with bureaucratic compliance cultures left him frustrated (Mace 1980). Mace (1985, 147) coined the term “Universal Design” in 1985 to describe “a way of designing a building or facility, at little or no extra cost, so that it is both attractive and functional for all people, disabled or not.” His article “Universal Design: Barrier Free Environments for Everyone” framed accessibility as a requirement for “good design” (just as disability activists had done in the late 1970s) (152).

Mace’s (1985, 152, 148) concept expanded the focus of barrier-free design to a broader population of marginalized users of built environments, from “young people with moderate mobility impairments [who] are placed in nursing homes” to “older couple[s]” to temporarily disabled workers and deaf or hard-of-hearing people. Mace also sought to expand accessibility by framing it as a necessarily interdisciplinary phenomenon involving architects, product designers, engineers, builders, and manufacturers alike in the process of building more accessible built environments as coordinated systems (148, 152). This interdisciplinary approach to “good design” pushed beyond checklist-style standards by requiring an understanding of how component parts of a space work in tandem to facilitate access. By emphasizing that Universal Design was a form of “good design,” Mace strategically framed accessibility for all users (a radical, challenging, and far-reaching imperative) as a simple, common sense practice. This enabled him to draw upon disability rights, culture, and anti-institutionalization positions to challenge architects’ conceptions of disabled people as an insignificant and powerless population and their assumptions about accessibility as inherently tied to distasteful institutional or medical aesthetics (148–149).

Like disability activists who emphasized that rehabilitation should not be a prerequisite for access and citizenship, Mace (1985, 150) argued that accessibility should be available even to those who do not have a formal disability diagnosis. Code compliance approaches often required people seeking barrier-free access to convince others of the degree of their impairment through a process that critical disability theorist Ellen Samuels (2014, 9) terms “biocertification” – for example, use of a wheelchair or assistive device or official proof of a diagnosis. In 1989, Mace and his colleague, disabled design expert Ruth Hall Lusher, framed Universal Design as a concept benefiting marginalized users regardless of medical biocertification.

Instead of responding only to the minimum demands of laws which require a few special features for disabled people, it is possible to design most manufactured items and building elements to be usable by a broad range of human beings including children, elderly people, people with disabilities, and people of different sizes. This concept is called universal design. It is a concept that is now entirely possible and one that makes economic and social sense. (Lusher and Mace 1989, 755)

It is significant to note that Mace and Lusher proposed that Universal Design foreground disability, rather than arguing (as later proponents would) that Universal Design is distinct from disability access. While foregrounding disability, they also framed Universal Design as a resource for alliance between categories of users that were marginalized by mainstream standards of good design (albeit in different ways and to qualitatively different degrees). In doing so, they adopted a cultural understanding of disabled people as a disadvantaged minority group that exists in relation to other spatially excluded populations, such as children, elderly people, and people of different sizes.

This early framing of Universal Design reveals attention to the dimensions of power and privilege that determine belonging in built environments. As design experts with mobility disabilities, Mace and Lusher were among those for whom a legal right to barrier-free design (however limited) was most thoroughly mandated (in the form of ramps, elevators, and automatic doors). They used their relatively privileged positions as disabled designers who were included in accessibility codes to advocate for those who were not – for “collective access,” as activists and scholars would later call it (Hamraie 2013; Mingus 2010). Their attention to the collective stakes of access implied that disability advocates must seek inclusive design not only for themselves, but for other marginalized populations as well.

Mace and Lusher’s approach closely matched a cultural understanding of disability that conveyed the ethos of alliance and affiliation over biocertification and standardization. Their framing disclosed a critical disposition toward disability, which David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder (2003, 10) describe as “a political act of renaming that designates disability as a site of cultural resistance and a source of cultural agency previously suppressed.” Affiliating disability with other categories of social discrimination enabled Mace and Lusher to identify resonances between architecture and design approaches that challenged the normate template. Interaction designer Graham Pullin (2009, 93) would later refer to this sense of collective affiliation as “resonant design,” which begins by including the most marginalized and then explores the benefits of those inclusions for broader populations. Mace and Lusher’s framing also captured disabled people’s resourcefulness in fostering interdependence and relationality: an ethos that feminist disability theorist Alison Kafer (2013) calls the “political/relational” dimensions of disability. These capacious political, relational, and resonant dimensions characterized disability-focused Universal Design in the late 1980s.

0 notes

Note

do you think ABA therapy is ableist/bad?

I don’t pretend to be an expert on it, and I’m not autistic myself, but from the limited research I’ve done, it seems to be that any therapy that focuses solely on reducing or increasing behaviours, and never actually addressing why those behaviours occur, is never going to be super helpful, and has the potential to be really harmful.

I think it’s harmful for largely the same reason that spanking is harmful - if a child is capable of understanding why what they’re doing is wrong, then you need to help them understand that what they’re doing is wrong. If they’re not capable of understanding, then simply lashing out at them whenever they do something you don’t like is not helpful.

ABA is practised widely in the US but isn’t as common in the UK, so everything I know about it I know from reading articles and personal accounts. And it seems to be the majority of autistic activists condemn the therapy, and that’s enough for me.

Because, unlike the mental health establishment, I believe that autistic people are reliable narrators of their own experiences.

Both the medical and mental health sectors are rife with ableism, as any person who is disabled, has a chronic illness, a mental illness, or is neurodivergent can tell you. And it seems to me that ABA therapy is the epitome of ableist psychology, which assumes that being a neurotypical “expert” makes yours the most reliable, and the most objective, trustworthy opinion.

When people who are actually autism advocates and activists are saying rather loudly that ABA is harmful, even traumatising for many children, the psychology community should listen and take note. Just because the autistic children they’ve treated with ABA therapy are more “acceptable” in their eyes, that doesn’t mean they haven’t caused any harm, and to deliberately ignore the opinions and experiences of people who are actually autistic when discussing a therapy designed for autistic children, is grossly irresponsible.

That’s what ABA therapy seems to boil down to... making autistic people more “acceptable” and more palatable to wider society.

If a child is engaging in any behaviour that directly harms themself or another person (like banging their head against a wall, or striking out and hitting other people), that behaviour needs to be addressed. But you need to figure out why they are behaving that way, and if they are capable of understanding that what they’re doing is not okay. Because if they genuinely aren’t capable of understanding that hitting others causes them harm, and that’s wrong, then the way to decrease that behaviour is to prevent or remove them from situations that might lead them to hit others or hurt themself.

But the reality is that the majority of autistic behaviour addressed by ABA therapy isn’t directly harmful to anyone, it’s just inconvenient for neurotypical people. It’s things like being non-verbal, or having vocal stims or ticks, it’s flapping hands or not making eye-contact. None of these things harm anyone, they’re just different behaviour than what we’re used to.

Advocates of ABA insist that the therapy aims to help them integrate into society. But if all our autism “treatment” consists of forcing autistic people to stop being who they are, rather than requiring neurotypical society to adjust to accommodate them, then really it’s just about trying to stop autistic people from being autistic. It sees autism and any autistic behaviour as inherently bad.

If a child is deeply distressed by the colour blue, why should they be forced to see it all the time and just expected to carry on as though they’re not deeply uncomfortable and stressed out? Why can’t we just... take down any blue paper and posters from the classroom walls? Why can’t we just... repaint the dining room or reupholster the sitting chair?

If a person is caused deep discomfort or even physical pain by looking people in the eye, why should they be forced to do it all the time to appease social niceties? Why can’t people just accept that this autistic person doesn’t mean anything rude by it, and just carry on with life because not having someone look us in the eye actually has zero effect on us?

If a child likes to spend hours pulling drawers in and out, or rolling dice, or watching sand fall through their hands, why force them to fill their time with something else that you’ve deemed to be more ‘acceptable’ play? Why can’t you meet them where they are, and enjoy this activity with them that is clearly bring them a lot of peace or joy?

If a child is non-verbal, why try to force them to communicate in a way that makes them uncomfortable or isn’t accessible to them, when we could just as easily learn to communicate with them in a different way, by using pictures, or using makaton, for example? It’s like trying to force a deaf child to read lips and speak verbally... you just have to accept that they are experiencing the world differently, and learn something new so that you can meet them where they are.

I absolutely believe that we should do our best to give children the ability to cope with the outside world, and all the challenges it will bring. And the reality is that life is pretty inaccessible to autistic people a lot of the time, and that makes it harder for them. But any therapy for autistic children should aim to help them find ways to cope with things that make them uncomfortable, give them tools to help them communicate, and understand what they’re feeling and how to deal with those feelings in a healthy way, not force them to conform to whatever neurotypical society has deemed as ‘acceptable’ social behaviour.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Experiment continued

Today we started our work by discussing whether haptic feedback could be better used for feedback on “correct” or “incorrect” coping with the use of an artifact. On one hand, when paired with output on a screen, vibration can become annoying or overwhelming. Just a pen suggests certain incorrect graspings by being uncomfortable to hold, for example. On the other hand, something inherent in the idea of feedback is that indicates reaction directly following action. For example, when you start an electric shaver, the vibration feedback from a motor indicates it is on. The question of whether the vibration is meant to be used as a positive or negative indication is one aspect of haptic signaling as guidance for skillful coping that we will continue to pursue.

Today we stuck with vibration as a positive indicator that the grasping is correct. To expand upon yesterday’s button example, we went 2 ways:

The closer one’s hand is to the intended position the more the vibration increases, indicating progress in grasping an object in use.

The more surface is pressing against one’s palm the more active feedback becomes. The implementation was not successful today

A good tool is such that allows you to use it however you want. In other words, it allows people to suit it according to their bodies, it is relational in its affordances, “hinging on the agent’s bodily capabilities” (Heyer, 2018, p. 502). This also suggests the importance of accessibility and the danger an ableist design poses: crucial ethics for my design practice. After trying the first example we decided that from here the buttons must be embedded in a tangible artifact and we should move away from plain breadboard and arduino in order to better immerse ourselves in the experience. To do this we will proceed to make a shape that in its form lacks direct invitations to one way of holding/grasping only, so haptic feedback can overrule them to an extent. To speculate, perhaps a perfect tool to create here would be a plain artifact that could be programmed by users according to their grasping positions?

Heyer, C. (2018). Designing for Coping. Interacting with Computers, 30(6), 492-506.

0 notes

Text

Phase 2: FINAL Project Essay

In the modern age of technology, it’s extremely rare to find someone that leaves the house without their phone on them at all times. That is the basis of why we as a group, consisting of Michael, Munsu, Camil, and I, decided to come together to create a learning application on the phone. We were taking into account the fact that people may not have a computer at their disposal and only have a phone. In this way, we can be all inclusive of those that only have the ability to learn on the go rather than sit down in a traditional classroom, e.g. students working 3 jobs to pay the bills. We focused on building on business on the premise of teaching business aspects. Additionally, we also planned to make two distinctive features on the app so that it is accessible to all. However, the group and I decided to go our separate ways as they wished to pursue a different route of app learning. I decided to proceed with the project because I believed it’s important that everyone has equal access to business features. I have implemented both audio and sign language features so that both the hearing and vision impaired community are able to use our application without hindrances into the prototype. While there are other applications such as Khan Academy, Udemy, Lynda, Duolingo, etc., they are not inclusive in their methods of teaching. They all have read only formats with some having audio options. QuickEd, the application I created, attempts to address and remedy all these shortcomings. Since the midterm, I’ve reached out to someone in my targeted social salient identity audience and also an expert I consider to be knowledge on the field of working with physically disabled students.

Accessibility technology is not an advanced part of the app market. Apps generally market toward the general mass and do not offer accessibility options. Throughout the world, 5% of the population has some form of deaf/partial deafness (about 466 million people). In the United States alone, 1 in 20 Americans have some form of hearing disability. In regard to vision impairment, 285 million of the world’s population are affected. These are relatively small numbers in comparison to the global population of 7 billion+, however this does not mean that it’s to be regarded. If anything, it is because they are a minority that there should be more accommodation given – and this is where QuickEd steps in. With only every 4 out of 10 adult disabled Americans employed, it only shows a lack of ability by the able-bodied Americans to accommodate and provide working environments that are accessible to all. I hoped that in creating this app, an immersive experience was created in which both able bodied individuals and those with disabilities can be on the same level playing field – equity, rather than equality, for all. This is what we thought since the inception of the product, and I hoped that I have achieved that. One of the most important aspects of life, obtaining a job, is decided based on education. Disabled people are often not allowed the liberties that able-bodied people are. They either have to find a place that accepts and overlooks their differences or rely on government aid to get them get by – sometimes even needing to do both to sustain a working lifestyle as government funds alone do not provide much. QuickEd hopes that in the long term, it allows disabled bodies to be on the same playing field as able-bodied people by providing access to the same educational tools. I understand that I am not the first to think of this idea, however I have researched and seen the alternatives and have come to a resounding solution that the alternatives do not make the app user friendly, have too many errors and glitches, and are generally has less functionality than its regular counterpart. QuickEd App aims to be both user friendly and educational so that the difference between learning in a traditional classroom and learning via app is a seamless transition.

The persona my partner, Shiv, created was an app based businessman. I found this to be actually quite intriguing because they way he viewed my project was like a businessman on Wall St with an app icon for the head – what I perceive as the intersectionality between entrepreneurship and technology. In a way, the figure Shiv created really is what QuickEd aims for in the long term. We want to help the disabled community, those with hearing and vision impairment, become employed. Whether that’s through a business standpoint or using business skills to apply elsewhere, the app based businessman really is a culmination and visualization of what QuickEd personified could be.

Every disabled person’s journey to survive in an ableist world is different. While I cannot speak about their experiences and hardships to overcome the obstacles inherently placed in their path, I can discuss what I observed. Throughout my education, there were always special classes set aside for those with abilities and needing special accommodation. Though they were allowed to roam amongst the other students during recess/break times, their learning environment was always separated from the “regular” students. No matter how much integration was placed to make them feel a part of the student population, because fundamentally their classrooms and lectures were designed differently from regular coursework – they were never truly a part of the mass. As a child growing up, belonging and fitting in is universally known to be the biggest social problem, no matter the circumstances; nobody wants to stick out or be different. Drawing on our own different experiences collectively, the four of us conceived the idea to create QuickEd. Our ultimate goal of this project is to provide the disabled community the same privileges that able bodied have had for the past centuries through education.

When reading sections of Technology Choices: Why Occupations Differ in Their Embrace of New Technology, specifically the chapter “the role of occupational factors in shaping technology choices” (p170-194), reminded me of our project. The premise of the whole book is based around their claim that “occupational factors strongly shape technology choices in the workplace” (169). With the technological revolution fully well on its way, providing an opportunity and a competitive quality to disabled youth/adults and in turn perhaps lead to an occupation in the future is long-term side effect that QuickEd wishes to have. I then asked myself, how can QuickEd be applied to make it useful for people in most if not all fields? After I was able to decipher the large number of unnecessarily big words throughout the chapters, I realized that the ideas they presented were extremely relatable. To put all of the ideas condensed into a single example, the Levy and Murnane findings show no better result. Essentially, they exposed the processes and procedures of what cardiologists do to machines/computers but found that the computers could only complement the processes, not take over. Similarly, we have to understand that while QuickEd may be creating a revolutionizing slice in the eyes of the disabled community, it is not a means to take over the educational sector. In the book Diversity and Design: Understanding Hidden Consequences Anthony discusses the height of a podium in relation to her confidence in the section gender and sexuality. She says that, “for many speakers, a highly noticeable, uncomfortable mismatch occurs where the relationship between the speaker and podium mis out of proportion” (195), which I related to in terms of how QuickEd is really trying to bridge that gap of disproportionality between education and occupation in the disabled community. QuickEd only serves to supplement and complement the existing technologies in place to make it an equally immersive learning tool/environment for the disabled community.

With a goal in mind, our group set out to create a product and I focused on perfecting it. I had taken the prototype and elevated it to the best of the ability. Since the midterm, the project has been tweaked to add basic business information and also financial functions except now I programmed it into a working prototype that can be test driven for feedback. Having minimal experience in computer programming languages, I enlisted the help of my CS peers to help me code a working app that I could prototype to my targeted SSI contact and expert contact. I primarily used Appy Pie as it’s a free software (with ads) that allows the user to create apps on a cloud software.

I had made initial contact with Adule Dajani, a student that’s currently studying in University of San Francisco who is hearing impaired. As one of my best friends from high school, it was important for me to create this project and for her to approve of it as useful and educational – as a result I turned to her for my contact. I scheduled a FaceTime call with her on April 16th. After the initial catching up and talking, we discussed my project. I had sent her a working prototype of my app that she could test drive and give me constructive feedback. I asked about her experience learning in high school and in college and how they are in comparison to each other. She made sure that what she said in this interview was not speaking for those in the community or the community as a whole as her experiences differs from others. She proceeded to say that because she is only partially deaf, she had a relatively easier time adjusting to classes. She often how classes were ableist and would affect her studies “but only slightly.” She had to learn how to adjust herself to the classroom and either sit closer to the front of classroom or specifically ask the teacher to speak louder. While these seem like easy fixes, they show how the disabled individual has to adjust themselves and adapt to the environment already in place – a space that was created with no thought to how inclusive the space is. She told me how she never really thought about how she had to conform herself to the environment because she was so used to it – she’d been doing it since she began incrementally losing her hearing. When test driving my app, she said that she could see where I was trying to take this app and what I was trying to do with it, but there were a lot of technical errors that kept happening (which I also ran into while product testing). Technical issues aside, she found that it was actually quite useful is teaching basic business to the masses. While I had explained to her my reasoning for not including closed captioning (mistranslations and misheard words could lead to big misunderstandings versus sign language is universal and cannot be misinterpreted), she told me it would be beneficial to include the option to have that as well. She did tell me that the sign language was a good idea as it’s easy to understand and she hasn’t seen that before in an educational app. Taking into account her feedback, if I were to continue with this project I would try to fix the technical issues, implement closed captioning, maybe expand my business model and/or add lessons.

The expert opinion I contacted was my high school health teacher who also teaches a special education class and leads a Peer Helping after school club that focuses on the student body and providing more inclusive spaces (mentally and emotionally) as well as focusing on student health. Ms. Kelly Alberta (or as we called her Ms. Lighty) was always one of those teachers on campus that you know you could go to for whatever reason and she would help in any way that she could. Teachers that show genuine care and also have the ability to make students feel safe and open are rare and hard to come by – a main reason why she resonated with so many members of the student body. I initially contacted Ms. Lighty because I knew that even after 4 years of being out of high school, I could still turn to her with any problems I had and she would help. She responded the following week with my answered questionnaire document. With my expert opinion, rather than focus primarily on receiving feedback for my app, I wanted to know what it’s like to teach these students and what kind of barriers she and they face especially amongst an able-bodied community. She did ask that while she was happy to answer my questions, she ask that her answers be not made public and I instead summarize what she said for each question if need be. Out of respect for her wishes, I won’t be showing the document but will be showing my initial contact e-mail to her. One of the main takeaways I got from her document is that her physically disabled students, whether it be inability to walk, inability to see, or inability to hear, they all just want one thing and that is to have friends. But from her perspective, she often finds herself wondering if the students that have graduated are doing well and are living mostly independent and happy lives. She worries that the outside society does not cater to them – which it does not – and how they will find jobs after graduation. In a capitalistic society, this is an extremely valid concern. In my questionnaire, I explain that my reasoning for choosing to educate people on basic business aspects and financial literacy. Ms. Lighty wrote that she sees the idea behind why I would choose business and suggested that rather only offer financial literacy (which is what I had programmed for the work-like prototype) I should also offer basic business education. I took this in stride and reorganized and reformatted the app so that it also offers basic business training and aspects.

The biggest question I ask myself and I had others ask me is why we chose business and why I chose to continue with business education and how that intersects with ableism and helping the disabled community. Business, I personally believe, can be applied anywhere. The tactics and skills learned through how to start, run, and manage a business remains relevant throughout all fields of life. More importantly the social skills that are understood and leadership qualities developed shine through in any field of work. Having studied business for four years, the different tactics used in how to approach people, conflict resolution, how to be convincing – these are all skills that are important to business yet are transferable to any other skill set. Allowing the disabled community, specifically targeting those with hearing and vision impairment, to hone in these skills gives them a competitive advantage and an edge just to have a fighting chance like everybody else.

Looking towards the future, I believe QuickEd really is on the right path to becoming, if not already, a revolutionary product that equals the playing field. What I would do next is do widespread rollout of the app. I have already incorporated what I believe at this point the very best culmination of material needed for success. What’s now needed is mass user feedback. I could add a “contact us” section or a page that allows for feedback from users. At this point, we could even do an exchange of survey results for compensation i.e. complete this survey for $5 Amazon gift card! Another idea I had was to take the app to be able to work offline. In major hubs like New York City, Chicago, and San Francisco public transportation and underground trains allow for a lot of downtime with or without internet. Allowing commuters to access the app without internet would provide a new aspect of convenience that may appeal to an untapped target market.

Works Cited

Alberta, Kelly. Personal communication. 3 May. 2019

Bailey, Diane E., and Paul M. Leonardi. Technology Choices Why Occupations Differ in Their Embrace of New Technology. The MIT Press, 2015.

Dajani, Adule. Personal interview. 16 Apr. 2019

Tauke, Beth, et al. Diversity and Design: Understanding Hidden Consequences. Routledge, 2015.

“Deafness and Hearing Loss.” Who.intl, World Health Organization, 28 Nov. 2018, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss.

“GLOBAL DATA ON VISUAL IMPAIRMENTS 2010.” who.intl, World Health Organization, 2012, www.who.int/blindness/GLOBALDATAFINALforweb.pdf.

0 notes

Text

Midterm Project: QuickEd

In the modern age of technology, it’s extremely rare to find someone that leaves the house without their phone on them at all times. That is the basic reasoning of why we as a group, consisting of Michael, Munsu, Camil, and I, decided to do a learning app on the phone. We were taking into account the fact that people may not have a computer at their disposal and only have a phone. In this way, we can be all inclusive of those that only have the ability to learn on the go rather than sit down in a traditional classroom, e.g. students working 3 jobs to pay the bills. Additionally, we also plan to make two distinctive features on the app so that it is accessible to all. We are implementing both audio and sign language features so that both the hearing and vision impaired community are able to use our application without hindrances. Applications such as Khan Academy, Udemy, Lynda, Duolingo, etc. are not inclusive in their methods of teaching. They all have read only formats with some having audio options. QuickEd, the application we are creating, attempts to address all these problems.

Accessibility technology is not an advanced part of the app market. Apps generally market toward the general mass and do not offer accessibility options. Throughout the world, 5% of the population has some form of deaf/partial deafness (about 466 million people). In the United States alone, 1 in 20 Americans have some form of hearing disability. In regard to vision impairment, 285 million of the world’s population are affected. These are relatively small numbers in comparison to the global population of 7 billion+, however this does not mean that it’s to be regarded. If anything, it is because they are a minority that there should be more accommodation given – and this is where QuickEd steps in. We hope that in creating this app, we create an immersive experience in which both able bodied individuals and those with disabilities can be on the same level playing field – equity, rather than equality, for all. In addition to the educational aspect, education is the basis for all things in life. One of the most important aspects of life, obtaining a job, is decided based on education. Disabled people are often not allowed the liberties that able bodied people are. They either have to find a place that accepts and overlooks their differences or rely on government aid to get them get by. QuickEd hopes that in the long term, it allows disabled bodies to be on the same playing field as able bodied people by letting them access the same educational tools. We understand that we are not the first to think of this idea, however we have researched and seen the alternatives and have come to a resounding solution that the alternatives do not make the app user friendly, have too many errors and glitches, and are generally has less functionality than its regular counterpart. QuickEd App aims to be both user friendly and educational so that the difference between learning in a traditional classroom is a seamless transition.

Every disabled person’s journey to survive in an ableist world is different. While I cannot speak about their experiences and hardships to overcome the obstacles inherently placed in their path, I can discuss what I observed. Throughout my education, there were always special classes set aside for those with abilities and needing special accommodation. Though they were allowed to roam amongst the other students during recess/break times, their learning environment was always separated from the “regular” students. No matter how much integration was placed to make them feel a part of the student population, because fundamentally their classrooms and lectures were designed differently from regular coursework – they were never truly a part of the mass. As a child growing up, belonging and fitting in is universally known to be the biggest social problem, no matter the circumstances; nobody wants to stick out or be different. Drawing on our own different experiences collectively, the four of us conceived the idea to create QuickEd. Our ultimate goal of this project is to provide the disabled community the same privileges that able bodied have had for the past centuries through education.

When reading sections of Technology Choices: Why Occupations Differ in Their Embrace of New Technology it reminded me of our project. How can we apply QuickEd and make it useful for people in most if not all fields? After I was able to decipher the large number of unnecessarily big words throughout the chapters, I realized that the ideas they presented were extremely relatable. To put all of the ideas condensed into a single example, the Levy and Murnane findings show no better result. Essentially, they exposed the processes and procedures of what cardiologists do to machines/computers, but found that the computers could only complement the processes, not take over. Similarly, we have to understand that while we may be creating a revolutionary product in the eyes of the disabled community, it is not a means to take over the educational sector. QuickEd only serves to supplement and complement the existing technologies in place to make it an equally immersive learning tool/environment for the disabled community.

As I worked on the iteration and prototyping for this app, I ran into a lot of technical issues. While I have created the images of what the app would look like throughout the stages, I need to figure out how to get it working in reality. Additionally, I wish to make it look more natural and integrate the sign language and audio features more seamlessly. The next step would to be solve these problems, integrate more features, conduct more research on the problems it would be solving, what problems we missed via research of what disabled community needs. One of the biggest differences and next steps I will need to continue for is that actual run through of the app and make it a working one that we can test drive.

Works Cited

Bailey, Diane E., and Paul M. Leonardi. Technology Choices Why Occupations Differ in Their Embrace of New Technology. The MIT Press, 2015.

“Deafness and Hearing Loss.” Who.intl, World Health Organization, 28 Nov. 2018, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss.

“GLOBAL DATA ON VISUAL IMPAIRMENTS 2010.” who.intl, World Health Organization, 2012, www.who.int/blindness/GLOBALDATAFINALforweb.pdf.

0 notes