#bix beiderbecke and his gang

Text

Day Eight Hundred and Ninety Two

Stop the traffic to Dixie

Hold it right on the line

Don't want nothing come betwixt me

And that ol' home of mine

1 note

·

View note

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

MEZZ MEZZROW, DE L’ÉCOLE DE RÉFORME AU SWING

Né le 9 novembre 1899 à Chicago, en Illinois, Milton Mesirow, dit Mezz Mezzrow, était issu d’une famille d’immigrants russes d’origine juive. Mezzrow a appris à jouer du saxophone à la Potomac Reformatory School où il a été incarcéré à partir de l’âge de seize ans pour avoir volé une automobile. Selon un de ses biographes, Mezzrow, avait fait de nombreux séjours dans les écoles de réforme et les prisons avant de découvrir le jazz et le blues à la fin de son adolescence. Trouvant une sorte de rédemption dans la musique, Mezzrow avait alors tenté d’imiter ses idoles Freddie Keppard, Joe Oliver, Louis Armstrong et Jimmy Noone.

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

À la fois clarinettiste et saxophoniste ténor, Mezzrow avait enregistré à la fin des années 1920 avec les Jungle Kings, les Chicago Rhythm Kings et le groupe d’Eddie Condon. Il avait aussi joué avec un groupe appelé le Austin High Gang. En compagnie d’autres musiciens blancs comme Eddie Condon et Frank Teschemacher, Mezzrow s’était rendu au Sunset Café de Chicago où il avait pu entendre Louis Armstrong et son célèbre Hot Five. Mezzrow admirait tellement Armstrong qu’après la publication du classique "Heebie Jeebies", il avait parcouru la distance de 53 miles jusqu’en Indiana avec Teschemacher pour pouvoir jouer la pièce devant Bix Beiderbecke.

C’est en 1927 que Mezzrow s’était installé à New York et avait commencé à jouer avec Eddie Condon.

Dans les années 1930, Mezzrow avait joué avec différents groupes de swing aux côtés de grands noms du jazz comme Benny Carter et Teddy Wilson. Durant la même décennie, Mezzrow, qui avait contribué à briser la barrière raciale, avait également dirigé un groupe multi-ethnique appelé les The Disciples of Swing. Le groupe était notamment composé d’Eugene Cedric au saxophone ténor, de Mezzrow à la clarinette, de Frank Newton, Sydney De Paris, Max Kaminsky et Dolly Armendra à la trompette, de George Lugg et Vernon Brown au trombone, d’Elmer James au tuba, de John Nicolini au piano et de Zutty Singleton à la batterie. Durant une brève période, Mezzrow avait aussi été le gérant de Louis Armstrong.

Avec l’orchestre de Tommy Ladnier, Mezzrow avait aussi enregistré le thème musical qui l’avait fait connaître et intitulé “Really The Blues”.

Mezzrow a fait ses débuts sur disque en 1933 avec un groupe appelé Mezz Mezzrow And His Orchestra. La formation, qui était surtout composée de musiciens de couleur, comptait dans son alignement des grands noms du jazz comme Benny Carter, Teddy Wilson, Pops Foster et Willie "The Lion" Smith, mais comprenait également le trompettiste d’origine juive Max Kaminsky. Mezzrow a également participé à six enregistrements de Fats Waller en 1934.

Un des grands moments de la carrière de Mezzrow à cette époque avait été un enregistrement en 1938 organisé par le producteur français Hugh Panassie, qui était devenu un de ses grands amis et qui l’avait réuni à son idole Sidney Bechet. Tommy Ladnier participait également à l’enregistrement.

Grand admirateur de Bechet, Mezzrow avait fondé sa propre maison de disques appelée King Jazz, qui avait été en activité de 1945 à 1947 et qui lui avait permis d’enregistrer fréquemment avec Bechet au milieu des années 1940 ainsi qu’avec le trompettiste Oran "Hot Lips" Page. Même si Mezzrow était loin d’arriver à la cheville de Bechet, on doit lui accorder le mérite de s’être trouvé au bon endroit au bon moment, ce qui lui avait permis de participer à plusieurs enregistrements avec Bechet et d’autres grands noms du jazz, tant à New York qu’à Chicago de 1945 à 1947. Ces enregistrements, qui mettaient en vedette le Mezzrow-Bechet Quintet et le Mezzrow-Bechet Septet, mettaient à contribution des musiciens de couleur comme Frankie Newton, Sammy Price, Tommy Ladnier, Sid Catlett, ‘’Pleasant'' Joe ainsi qu’Art Hodes, un musicien blanc né en Ukraine.

DERNIÈRES ANNÉES

Après avoir participé en 1948 au Festival de Jazz de Nice, Mezzrow s’est installé en France, où il s’était rapidement acquis le respect des musiciens de jazz locaux. Durant son séjour en France, Mezzrow avait fondé plusieurs groupes composés à la fois de musiciens français comme Claude Luter et de musiciens américains de passage comme Buck Clayton, Peanuts Holland, Jimmy Archey, Kansas Fields, Lee Collins et Lionel Hampton. Avec Clayton, un ancien trompettiste de l’orchestre de Count Basie, Mezzrow avait enregistré une version du classique "West End Blues" de Louis Armstrong en 1953.

Dans les années 1950, Mezzrow a continué d’enregistrer pour plusieurs compagnies de disques françaises.

Mezzrow est demeuré en France jusqu’à sa mort dans un hôpital américain de Paris le 2 août 1972. Il était âgé de soixante-treize ans. Le décès de Mezzrow a été attribué à une crise d’arthrite qui avait atteint sa moelle épinière. Mezzrow a été inhumé au cimetière du Père-Lachaise. À l’époque, l’épouse de Mezzrow, Johnnie Mae Mezzrow, était déjà décédée. On survécu à Mezzrow son fils Milton H. Mesirow, ainsi que ses deux frères domiciliés en Illinois.

Même si Mezzrow était d’origine et de religion juive, il avait épousé une afro-américaine, Johnnie Mae, qui était de religion baptiste. Le couple a eu un fils, Milton H. Mesirow, Jr. Au cours d’une entrevue qu’il avait accordée au New York Times en 2015, "Mezz Jr.", comme il était surnommé, avait déclaré qu’il avait toujours vécu entre deux cultures. Comme il l’avait souligné, "My father put me in a shul, and my mother's side tried to make me a Baptist. So when I'm asked what my religion is, I just say 'jazz.'"

Même si Mezzrow était un saxophoniste et un clarinettiste compétent, Mezzrow était surtout connu pour son autographie intitulée We Called It Music, qui avait été publiée à Londres en 1948. Même s’il était blanc, Mezzrow avait toujours admiré la culture afro-américaine. Dans son autobiographie, Mezzrow avait même catégoriquement rejeté la société blanche et revendiqué la culture afro-américaine. Dans son ouvrage, Mezzrow avait écrit qu’à partir du moment où il avait été mis en contact avec le jazz, il était devenu a ‘’Negro musician, hipping [telling] the world about the blues the way only Negroes can." Eddie Condon avait confirmé: "When he fell through the Mason–Dixon line he just kept going". Avec sa famille, Mezzrow vivait à Harlem. Se définissant lui-même comme ‘’Negro’’, Mezzrow était d’ailleurs décrit comme tel sur sa carte de mobilisation émise durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. L’autobiographie de Mezzrow, qui se concentre principalement sur les décennies de 1920 et 1930, malgré certaines inexactitudes historiques, constitue une des rares autobiographies écrites par un des premiers musiciens de jazz, tout en étant aussi une des mieux documentées et des plus divertissantes.

Grand consommateur de marijuana dont il faisait la promotion dans sa musique, Mezzrow était également reconnu comme ‘’dealer.’’ Surnommé ‘’Muggles King’’ (le mot Muggles étant un terme de slang désignant la marijuana), Mezzrow fournissait également de la marijuana à Louis Armstrong qui était un de ses meilleurs clients. La chanson de 1928 d’Armstrong intitulée "Muggles" fait d’ailleurs explicitement référence à Mezzrow. Dans une de ses lettres écrite en 1932, Armstrong précisait d’ailleurs comment et à quel endroit Mezzrow vendait de la marijuana.

En 1940, Mezzrow a été arrêté sous l’inculpation d’avoir été en possession de soixante joints de marijuana alors qu’il tentait d’entrer dans un club de jazz afin d’en faire le trafic. Au moment d’entrer dans sa cellule, Mezzrow avait informé les gardiens qu’il était noir et qu’il devait être envoyé dans la section réservée aux prisonniers de couleur. Dans son ouvrage Really the Blues, Mezzrow écrivait:

‘’Just as we were having our pictures taken for the rogues' gallery, along came Mr. Slattery the deputy and I nailed him and began to talk fast. 'Mr. Slattery,' I said, 'I'm colored, even if I don't look it, and I don't think I'd get along in the white blocks, and besides, there might be some friends of mine in Block Six and they'd keep me out of trouble'. Mr. Slattery jumped back, astounded, and studied my features real hard. He seemed a little relieved when he saw my nappy head. 'I guess we can arrange that,' he said. 'Well, well, so you're Mezzrow. I read about you in the papers long ago and I've been wondering when you'd get here. We need a good leader for our band and I think you're just the man for the job'. He slipped me a card with 'Block Six' written on it. I felt like I'd got a reprieve.’’

En 2015, un club de jazz a été nommé en l’honneur de Mezzrow à Greenwich Village. Le club était simplement baptisé ‘’Mezzrow.’’

Au cours de sa carrière, Mezzrow a enregistré environ 150 pièces et s’est produit vec les plus grands noms du jazz, de Sidney Bechet à Django Reinhardt, en passant par Frank Teschemacher, Eddie Condon, Tommy Ladnier, Max Kaminski, ‘’Hot Lips’’ Page, Buck Clayton, Lionel Hampton, Sid Catlett, Teddy Wilson, Fats Waller, Pops Foster, Benny Carter, Zutty Singleton, Jack Teagarden, Willie "The Lion" Smith et Memphis Slim.

Malgré le succès remporté par Mezzrow au cours de sa longue carrière, le producteur de disques Al Rose s’était montré plutôt sceptique face à son talent de clarinettiste. Rose avait cependant reconnu à Mezzrow le soutien qu’il avait accordé aux musiciens dans le besoin et avait souligné "his generosity and his total devotion to the music we call jazz." Dans son autobiographie, Mezzrow avait d’ailleurs admis avoir ‘’définitivement traversé la ligne qui séparait les identités blanches et de couleur.’’ Qualifiant Mezzrow de “Baron Munchausen du jazz”, le critique Nat Hentoff avait déclaré à son sujet qu’il avait joué “so consistently out of tune that he may have invented a new scale system.”

©-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

SOURCES:

‘’Mezz Mezzrow.’’ Wikipedia, 2024.

‘’Mezz Mezzrow.’’ All About Jazz, 2024.

‘’Mezz Mezzrow, 73, Clarinetist Who Was a Titan of Jazz, Dead.’’ New York Times, 9 août 1972.

‘’Milton ‘’Mezz’’ Mezzrow.’’ The Syncopated Times, 2024.

‘’Mezz Mezzrow, 73, Clarinetist Who Was a Titan of Jazz, Dead.’’ New York Times, 9 août 1972.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I was tagged by the wonderful @wayfaring-revolutionary for this, thank you very much!

rules: put your entire music library on shuffle and list the first 10 that come up. then tag 10 others to do the same.

I did something very similar to this recently, but I’ll see what songs pop up this time.

1. Darktown Strutters Ball by the Original Dixieland Jass Band (1918)

2. China Boy by Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra (1929)

3. At the Jazz Band Ball by Bix Beiderbecke and his Gang (1927) this is one of my favourite songs

4. Why Couldn’t It Be Poor Little Me by Ben Bernie and his Orchestra (1925)

5. King Porter Stomp by Jelly Roll Morton (1924)

6. Over There by Nora Bayes (1917)

7. Whispering by Red Nichols and His Five Pennies (1928)

8. There’ll Come a Time by Bix Beiderbecke (1927)

9. Love Her By Radio by Billy Jones (1922)

10. It’s a Long Long Way to Tipperary by Billy Murray and the American Quartet (1914)

Like I said in that other post, I have very strange taste in music because I was born in 1904 Thanks again for tagging me!

I tag @hobbadehoy, @made-by-our-history, @akkerdistel, @gecrgemackays, @where-colonel-mackenzie, @heavy-focking-metal, @my-little-kraken, @this-side-of-f-scott-fitzgerald, @thefyuzhe, and @rubinstein1798, if any of you would like to do this! I’m sorry if you’ve already done this, please feel free to ignore this post if you’d like.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

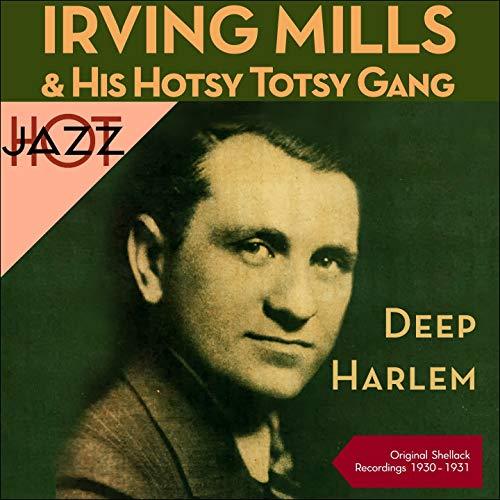

Irving Mills & His Hotsy Totsy Gang (w Bix Beiderbecke, Benny Goodman & J. Teagarden) – Deep Harlem

The Hotsy-Totsy Gang records made under Irving Mills name between 1928 and 1930 assembled some of the greatest White Jazz musicians of the era and often produced spectacular results. Sometimes Mills sang on the records, other times he just arranged the record dates and selected the musicians. As a singer Mills was not without talent (RedHoJazz).

Personnel:

Irving Mills – bandleader

Bix Beiderbecke – cornet

Ray Lodwig – trumpet

Jack Teagarden – trombone

Benny Goodman – clarinet, tenor saxophone

Min Leibrook – baritone saxophone

Joe Venuti, Matt Malneck – violin

Frank Signorelli – piano

Gene Krupa – drums

1 note

·

View note

Video

Boop-de-booop-ba-ba-de-doop!

See if you can spot the references, sharpshooters~

(Music - At the Jazz Band Ball - Bix Beiderbecke and His Gang, 1927)

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bloglet

Sunday, September 6, 2020

Still no response from General John Kelly, who is being trashed by the Trump gang. Among them are a few ex service guys who say we should consider all of the good things the president has done for our veterans (and put out of our minds things he might have said). But we note that Trump is taking credit for improvements he inherited. What he says has to be ignored, I suppose. Verbally abusive people like to say: oh, those are just words. One thinks of the drunk at the end of the bar or the uncle at the swimming pool who’s had one too many beers. Dubya often sounded like a drunk. He and Trump are a pair.

General John Kelly yet to comment. Here is Stephanie Grisham’s take on it: “(He) was totally unequipped to handle the genius of our great president.”

Beautiful weather. Outdoor seating doing great business at local eateries. No word yet about indoor dining. This means fewer diners and that more places have to close. They are, for now, struggling to survive.

Movie by way of Netflix: “Blackboard Jungle.” Starts with a drum solo. Of course, I’d forgotten this. Saw it so long ago. Saw it, if I have the math right, when I was fifteen. I didn’t know much at that age. A music credit for Stan Kenton. I wouldn’t have known the name. A snippet of Bix Beiderbecke. (I wouldn’t have recognized that name either.) And, of course, “Rock Around the Clock”...that had ‘em dancing in the aisles. Now, that...I knew. It was being played on the radio.

Note: I looked the movie up: There was more than dancing in the aisles. There was vandalism. The movie was banned in a few towns. I am not sure how it made it to Oak Ridge but am positive I saw it at the Ridge Theater, where I went every week. My mother may have attempted to talk me out of seeing this movie. I don’t remember, but already there was talk of juvenile delinquency, of which this film had plenty. Funny too, and characteristic of movies about high schoolers, many of the students look to be well into their twenties.

Breakout role for Sidney Poitier...

It brings to mind another movie. “Up the Down Staircase” with Sandy Dennis. Odd, the stories are so similar.

Monday, September 7, 2020

Kenichi sends me some photos. He is upstate, happily doing his off-road Jeep thing, called mudding. (I don’t think he’s had to sell off any of his vehicles.) His Jeep has this vanity plate: Must Mud.

Trump does a news briefing. It’s at the North Portico of the White House. Can’t use the Rose Garden because it’s under construction after Melania’s involvement. (Something gone wrong here. Flooding.) Trump tells a reporter to take his mask off. (Tough guy. Masks are for sissies.) Says we should have a vaccine in time for the election. (The scientists, who have lately been overlooked [Fauci says: I feel like the skunk at the picnic] say the odds against this are staggering.

The death toll mounds. Schools that were urged to reopen have many new cases. They reopened, partied and became ill. And now are quarantining in their dorms. No one listens.

0 notes

Photo

Bix Beiderbecke and His Gang / Goose Pimples (1927) The Bixbeiderbecke Story volume1-2-3 45RPMの7インチが一箱12曲入り✖️3箱 新鮮な果物ようなサウンド 78RPMのSP盤を蓄音器で聴いてみたい #bixbeiderbecke #microgroove #nonbreakable #popfreak宇都宮 https://www.instagram.com/p/B3aVM7gJHEL/?igshid=1baci1zdki07d

0 notes

Audio

Thirty Days of Jazz: Day 9

Louisiana | Bix Beiderbecke and His Gang

#louisiana#Bix Beiderbecke#jazz#bix beiderbecke and his gang#30jazz#using a pic of bix&tram bc jazz bb feels#music#my music

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

MUGGSY SPANIER, POUR L’AMOUR DU DIXIELAND

"…Muggsy plays a truer, more Negroid, more authentic jazz style than any other contemporary white jazz cornetist. He’s based his style closely upon the pattern of Oliver’s, at the same time taking a lot from [Louis] Armstrong but never falling under the influence of [Bix] Beiderbecke."

- Alma Hubner

Né le 9 novembre 1901 à Chicago, Francis Joseph "Muggsy" Spanier a d’abord commencé à jouer de la batterie, avant de passer au cornet dans le cadre d’un engagement avec Elmer Schoebel en 1921, avec qui il avait amorcé sa carrière professionnelle.

Comme la plupart des jeunes de son âge, Spanier rêvait de devenir un joueur de baseball professionnel. Spanier a d’ailleurs adopté le surnom de ‘’Muggsy’’ pour rendre hommage à John "Muggsy" McGraw, un gérant des Giants de New York de la Ligue nationale de Baseball. Spanier avait plus tard déclaré au sujet de McGraw: "McGraw knew what he wanted, and he’d run right after it without considering the consequences. That’s the way I played (jazz), on impulse, without figuring out the ‘why’ or ‘what’…and I didn’t do so badly."

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

C’est après avoir entendu Joe ‘'King'' Oliver jouer au Royal Gardens Cafe que Spanier s’était tourné vers le jazz. Spanier n’avait jamais reçu de leçons d’Oliver, mais il avait étudié son jeu avec attention. Spanier appréciait particulièrement le fait qu’Oliver restaut toujours collé à la mélodie tout en jouant très peu de notes. Décrivant sa collaboration avec Oliver, Spanier avait commenté:

"I got to know Oliver quite well. Both he and Louis [Armstrong] encouraged me in my playing a lot. Joe sometimes would teach me some of his tricks with the mutes; I learned a lot from him. After a little practice I was invited to sit in with the band. I was the first one to do so…it must have seemed strange, a little kid blowing cornet with those two Titans! That’s one thrill I’ll never forget: having played with the two greatest cornetists in jazz!"

Une autre importante influence de Spanier était le groupe New Orleans Rhythm Kings, qu’il avait entendu pour la première fois en 1920 avec George Brunies au trombone. Évoquant la collaboration de Spanier avec le groupe, le chef d’orchestre Sig Meyer avait déclaré: "Muggsy was fired with enthusiasm, a love of playing, and had that tremendous drive that gave the band he worked with an unbelievable lift."

Spanier avait obtenu une des plus grandes chances de sa carrière lorsque Oliver l’avait invité à se joindre au Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band dans le cadre d’une performance au Lincoln Gardens. Spanier avait d’ailleurs utilisé la sourdine dont Oliver lui avait fait cadeau lors de ses futurs concerts et enregistrements jusqu’à la fin de sa carrière.

Après avoir joué avec le groupe Bucktown Five au début des années 1920, Spanier avait travaillé avec les meilleurs groupes de l’époque, dont ceux de Ray Miller et Ted Lewis. Spanier a fait ses débuts sur disque le 25 février 1924 aux célèbres studios Gennett de Richmond. En 1927, Spanier s’était également produit avec les Chicago Rhythm Kings, dont faisaient aussi partie Frank Teschemacher à la clarinette, Mezz Mezzrow au saxophone ténor, Eddie Condon au banjo et au chant, et Gene Krupa à la batterie. Spanier était de retour en studio l’année suivante avec le groupe les Jungle Kings qui comprenait les mêmes musiciens à l’exception de Krupa qui avait été remplacé par George Wettling à la batterie. Évoquant sa collaboration avec le groupe, Spanier avait commenté en 1939: "I'm trying to play the kind of music I used to play with Tesch [Frank Teschmacher] and the old Chicago gang. All the same, I wanted to be up-to-date too. I want to have the old Chicago in New Orleans tradition and yet be something contemporary and distinctive."

Spanier a également participé aux premiers enregistrements du jazz dit de Chicago, notamment dans le cadre de la version du standard “I Found A New Baby” des Chicago Rhythm Kings et du classique “There’ll Be Some Changes Made” mettant en vedette Frank Teschemacher, Joe Sullivan, Eddie Condon et Gene Krupa. Avec le groupe de Lewis, Spanier avait aussi fait des apparitions dans deux films: ‘’Is Everybody Happy?’’ (1929) et ‘’Here Comes The Band’’ (1935).

Après avoir quitté le groupe de Lewis en 1936, Spanier avait assuré la relève d’Harry James (qui s’était joint à l’orchestre de Benny Goodman) avec le groupe du batteur Ben Pollack. Durant une performance du groupe à La Nouvelle-Orléans en 1938, Spanier, qui souffrait d’un ulcère à l’estomac en raison de son importante consommation d’alcool, avait été transporté en catastrophe à l’infirmerie de Touro. Spanier n’avait eu la vie sauve que grâce à l’intervention du Dr Alton Ochsner. Spanier avait expliqué: ‘’Doctors gave me up for lost after all those operations and I still can't understand how I survived. I could've gone back with Ted Lewis; only people were telling him I couldn't play anymore. That's why I got this little gang together just to show them I'm still around!"

Spanier avait éventuellement exprimé sa reconnaissance à Ochsner en composant deux pièces à son honnneur: “Relaxin’ at the Touro”, qui était devenue sa chanson-thème, et “Oh, Doctor Ochsner!” Joe Bushkin, qui avait joué du piano sur “Relaxin’ at the Touro”, avait plus tard été crédité comme co-auteur de la pièce. Comme Bushkin l’avait expliqué plusieurs années plus tard: "When I finally joined Muggsy in Chicago (having left Bunny Berigan's failing big band) we met to talk it over at the Three Deuces, where Art Tatum was appearing." Muggsy was now playing opposite Fats Waller at the Sherman hotel and we worked out a kind of stage show for the two bands. Muggsy was a man of great integrity. "We played a blues in C and I made up a little intro. After that I was listed as the co-composer of 'Relaxin' at the Touro'".

Spanier avait passé deux ans avec le groupe de Ben Pollack.

Durant son séjour avec le groupe de Pollack, Spanier avait participé à un enregistrement célèbre avec les Mound City Blue Blowers, qui comprenait à l’époque Red McKenzie, Jimmy Dorsey et Coleman Hawkins. Certaines des sessions du groupe de Lewis mettaient également en vedette de grands noms du jazz comme Fats Waller, Benny Goodman, Frank Teschemacher et les frères Dorsey.

Après une convalescence d’un an, Spanier était retourné à Chicago où il avait formé son groupe le plus connu, le Muggsy Spanier’s Ragtime Band. Le groupe de huit musiciens était notamment composé de George Brunies (ou Brunis) au trombone et au chant, de Rod Cless à la clarinette, de George Zack ou Joe Bushkin au piano, de Ray McKinstry, Nick Ciazza ou Bernie Billings au saxophone ténor et de Bob Casey à la batterie. Le 28 avril 1939, le groupe avait participé à l’ouverture du Sherman House Hotel de Chicago.

En 1939, le groupe avait enregistré seize pièces pour les disques Bluebird, une filiale de RCA Victor. Très bien accueillis par les critiques et les musiciens, ces enregistrements qui avaient bientôt été connus sous le titre de ‘’The Great Sixteen’’ avaient même contribué à une renaissance temporaire du Dixieland. Spanier avait commenté au sujet de ces enregistrements: "People want to know why Victor didn't get me to record more of those Ragtime sides, for they were one of the biggest sellers. But they were not commercial stuff....So I imagine this answers the question."

Comme l’écrivait le critique Alma Hubner:

"Muggsy Spanier's Ragtime Band invaded the Sherman and established a new record by remaining there for five and a half months. The band had coast-to-coast radio hookups and the crowds at the Sherman Hotel went for it in a big way. It played good jazz, which was good listening or dancing, whichever way you were inclined. Bands like…Bunny Berrigan’s and Gene Krupa’s played opposite them, yet Muggsy’s boys always managed to steal the show. It wasn’t only Muggsy’s driving, inspired cornet that proved sensational to the general public opinion; it was the band as a whole as well. George Brunis and his tail-gate trombone plus his irrepressible flair for comedy gave the Ragtimers a solid basis for good showmanship. Rod Cless’ clarinet was inspired and inspiring. Then too, men like Pat Pattison, Bob Casey, George Zack, Joe Bushkin, Ray McKinstry, Nick Ciazza, Marty Greenberg, Don Carter and George Wettling added to the atmosphere of perfection."

En octobre 1939, le groupe s’était rendu à New York pour jouer au club Nick's de Greenwich Village. Malheureusement, le contrat du groupe avait pris fin prématurément le 10 décembre.

Même si les disques s’étaient très bien vendus, le groupe n’avait pu trouver suffisamment de travail pour poursuivre ses activités. Malgré son succès apparent, le groupe avait dû être démantelé au bout de sept mois.

En 1940, Spanier s’est installé à New York et avait joué avec Max Kaminsky, Miff Mole et Brad Gowans dans le cadre d’un célèbre enregistrement qui s’était fait connaître sous le nom de “Jam Session at Commodore”. En septembre de la même année, Spanier était retourné à Chicago et s’était joint au groupe de dixieland de Bob Crosby. Décrivant sa collaboration avec le groupe, Spanier avait précisé: "One of my greatest thrills was playing with the Crosby band. I enjoyed myself immensely. Those boys had the right spirit. Jess [Stacey], Eddie Miller, Bobby Haggart, Nappy Lamare and Ray Bauduc certainly made something out of that band." Décrivant le séjour de Spanier avec la formation, Jim Cullum avait déclaré: "During his touring days with the Bob Cats, whenever the band would find itself in a bar with a juke box, Muggsy would always play the Great 16 records." Durant sa collaboration avec le groupe, Spanier avait aussi fait des apparitions sur deux autres films, ‘’Let's Make Music’’ et ‘’Sis Hopkins.’’ En 1940, Spanier avait également co-dirigé un quartet avec Sidney Bechet surnommé le ‘’Big Four.’’

En 1941, Spanier avait finalement quitté le groupe de Crosby pour lancer son propre big band. La même année, le groupe avait entrepris un contrat à long terme au Arcadia Ballroom de New York. Le clarinettiste de La Nouvelle-Orléans Irving Fazola était une des grandes vedettes du groupe à l’époque. La formation était si populaire qu’elle s’était classéd en première position dans le cadre d’un sondage du magazine Melody Maker en Grande-Bretagne. Le big band avait finalement été démantelé en septembre 1943. Épuisé, Spanier était retourné à Chicago, puis à New York.

Après avoir mis fin aux activités de son groupe, Spanier avait dirigé plusieurs sessions sous son propre nom, notamment dans le cadre de concerts à Town Hall et de l’émission de Rudi Blesh intitulée ‘’This Is Jazz’’.

Dans les années 1940, Spanier avait également participé à deux célèbres sessions: la première dans le cadre de la suite en quatre parties de Milt Gabler intitulée “A Good Man Is Hard To Find”, et la seconde avec le quartet de Sidney Bechet. Toujours aussi populaire, Spanier avait terminé en 1945 au septième rang du palmarès annuel des lecteurs du magazine Down Beat, juste avant Dizzy Gillespie.

De 1944 à 1948, Spanier s’était produit principalement avec de petits groupes de New York. À l’époque, Spanier continuait de se produire régulièrement au club Nick’s de Greenwich Village, collaborant notamment avec des musiciens comme George Brunies, Darnell Howard, Truck Parham, Floyd Bean, Ralph Hutchinson, Barrett Deems, Bobby Gordon et Jack Maheu.

À partir de 1949, Spanier avait fait la tournée des États-Unis avec son propre sextet. Malgré le retour en force du Dixieland, Spanier, qui n’appréciait pas particulièrement le tuba et le banjo, avait continué à travailler avec les petites formations qui avaient contribué à son succès. Un jour, après s’être aperçu que le batteur avec lequel il se produisait s’était mis à jouer dans l’ancien style, Spanier s’était écrié: “Hey! Would you wear your grandfather’s shoes?”

DERNIÈRES ANNÉES

En 1950, Spanier avait reçu une invitation pour se produire au club Club Hangover de San Francisco. Avant de monter sur scèene, Spanier avait mis le feu aux poudres en prononçant des commentaires plutôt acerbes envers les nouveaux musiciens de Dixieland. Les partisans du Yerba Buena Jazz Band avaient été particulièrement scandalisés des propos de Spanier, mais comme ses performances au club Hangover avaient attiré de nombreux spectateurs, on n’en avait pas fait trop de cas. Même si son groupe était retourné jouer au club à l’automne 1950, Spanier avait continué de vivre à Chicago. Fait à signaler, à une époque où les groupes interraciaux étaient encore loin d’être la norme, le groupe de Spanier avait innové en alignant plusieurs musiciens de couleur. Le clarinettiste espagnol Phil Gomez avait même fait une tournée avec le groupe durant plus d’un an à partir de 1953.

En 1957, après avoir vendu sa maison et s’être installé définitivement à San Francisco, Spanier avait fait partie du groupe du pianiste Earl Hines (1957-1959). Parallèlement à sa collaboration avec Hines, Spanier travaillait parfois comme accompagnateur tout en participant à des tournées. Au cours de cette période, Spanier s’était également produit au Tin Angel (le club fut plus tard acheté par Kid Ory et rebaptisé le club On The Levee). En 1963, Spanier avait aussi joué au club Dominick’s de San Rafael avec un groupe composé de Jimmy Archey, Darnell Howard, Joe Sullivan, Pops Foster et James Carter. La même année, avec Bob Mielke au trombone et Earl Watkins à la batterie, Spanier avait également fait une apparition sur l’émission de télévision Jazz Casual animée par Jack Gleason. Entre les chansons, Spanier avait raconté ses débuts avec King Oliver et fait différentes remarques sur le Dixieland.

Victime de problèmes de santé après avoir fait une tournée aux États-Unis et avoir participé au Festival de Jazz de Newport, Spanier avait été contraint de prendre sa retraite en 1964.

Spanier s’est marié à deux reprises. À la fin des années 1940, Spanier avait d’abord épousé Ruth M. Gluck. En 1950, Spanier avait épousé en secondes noces Ruth Gries O’Connell. Cette dernière ayant eu deux fils de son mariage précédent, Spanier était devenu leur beau-père. Le premier, Tom Gries, était devenu scénariste et réalisateur à Hollywood. Il est mort en 1977. Le second, Charles Joseph Gries, s’était fait connaître professionnellement sous le pseudonyme de Buddy Charles, et est devenu chanteur et pianiste à Chicago. En 1956, Spanier se produisait à Chicago lorsqu’il avait appris que Charles donnait un concert dans un club voisin, le Black Orchid. Spanier se serait alors écrié: ‘’That's my boy."

Muggsy Spanier est mort à Sausalito, en Californie, le 12 février 1967. Il était âgé de soixante-cinq ans. Le critique Alma Hubner avait écrit au sujet du style de Spanier: "…Muggsy plays a truer, more Negroid, more authentic jazz style than any other contemporary white jazz cornetist. He’s based his style closely upon the pattern of Oliver’s, at the same time taking a lot from [Louis] Armstrong but never falling under the influence of [Bix] Beiderbecke."

©-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

SOURCES:

‘’Joseph ‘’Muggsy’’ Spanier (1906-1967).’’ The Red Hot Jazz Archives, 2024.

‘’Muggsy Spanier.’’ Wikipedia, 2024.

‘’Muggsy Spanier.’’ Stanford University, 2024.

‘’Muggsy Spanier.’’ All About Jazz, 2024.

0 notes

Text

I was tagged by the lovely @gecrgemackays for this. Thank you very much for tagging me :)

RULES: You can tell a lot about someone by the type of music they listen to. Hit shuffle on your media player and write down the first 20 songs, then tag 10 or more people. No skipping!

I listen to music on YouTube, and when I click shuffle on my main playlist it only really shuffles the songs towards the beginning... anyways, behold my strange taste in music...

1. Oui Oui Marie by Arthur Fields (1918)

2. Thou Swell by Bix Beiderbecke and his gang (1928)

3. At The Jazz Band Ball by the Original Dixieland Jass Band (1918)

4. Three Blind Mice by Frankie Trumbauer and his Orchestra (1927)

5. Your Mother’s Son In Law by Billie Holiday (1933)

6. In the Mood by Glenn Miller (1939)

7. I Didn’t Know by Jean Goldkette and his Orchestra (1924)

8. Livery Stable Blues by the Original Dixieland Jass Band (1917)

9. Feeling No Pain by Red and Miff’s Stompers (1927)

10. Chattanooga Choo Choo by Glenn Miller (1941)

11. Ostrich Walk by the Original Dixieland Jass Band (1918)

12. Royal Garden Blues by Bix Beiderbecke (1927)

13. Down Where the Swanee River Flows by the Peerless Quartet (1916)

14. Melancholy Baby by the Charleston Chasers (1928)

15. Dancing Shadows by the Paul Whiteman Orchestra (1928)

16. The Rhythm King by Bix Beiderbecke and his Gang (1928)

17. There’ll Come a Time by Red Nichols and his Five Pennies (1928)

18. Over There by Nora Bayes (1917)

19. Good Morning Mr. Zip Zip Zip by Eugene Buckley (Arthur Fields) and the Peerless Quartet (1918)

20. Dipper Mouth Blues by King Oliver (1923)

Yes, I listen to 1910s and 1920s music on a regular basis. What can I say, I’m a time traveller

Thanks again for the tag :)

I tag @hobbadehoy, @made-by-our-history, @my-little-kraken, @where-colonel-mackenzie, @a-british-guardsman, and @akkerdistel if any of you would like to do this!

8 notes

·

View notes

Audio

“At the Jazz Band Ball” (1927)

Bix Beiderbecke & His Gang

#bix beiderbecke#bix beiderbecke and his gang#a favorite song#at the jazz band ball#1927#1920s#music

26 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Bix Beiderbecke & His Gang - Rhythm King

Swing it high and swing it low, kids...

0 notes

Photo

Bix Beiderbecke and His Gang / Goose Pimples (1927) The Bixbeiderbecke Story volume1-2-3 45RPMの7インチが一箱12曲入り✖️3箱 新鮮な果物ようなサウンド 78RPMのSP盤を蓄音器で聴いてみたい #bixbeiderbecke #microgroove #nonbreakable #popfreak宇都宮 https://www.instagram.com/p/B3aVM7gJHEL/?igshid=1jcx7dvj74ck0

0 notes