#bradoriid

Text

Sculpt of the small bivalved arthropod Gladioscutum lauriei from the middle Cambrian of Australia (after Hinz-Schallreuter & Jones 1994).

Gladioscutum had a body only 2-3 mm long, but, being undoubtedly aware of its disappointingly small size compared to its cooler Cambrian cousins like radiodonts and trilobites, tried to make up for it with a pair of (presumably) front-facing spines that were at least as long as the rest of the head shield.

Other than improving its self-esteem, the function of Gladioscutum's extremely elongated spines is unknown. The enlarged spines of other small Cambrian bivalved arthropods have been suggested to fulfill a sensory role, but this remains speculative (Zhang et al. 2014).

References and notes:

Gladioscutum was originally described as an "archaeocopid", an order that is now known to be an artificial grouping of various small bivalved arthropod fossils superficially resembling modern ostracod crustaceans. To my knowledge, the affinities of Gladioscutum have not been reinvestigated since its initial description, but its appearance (marginal rims, valve lobation, ornamented surface, simple hinge line) and age seem bradoriid-y enough (Hou et al. 2001) for me to more or less confidently reconstruct it as one (top scientific rigour as always on this blog).

Appendage morphology is unknown in Gladioscutum - what little soft anatomy I have not modestly hidden under the head hield is based on the bradoriid Indiana sp. from the Chengjiang Biota (Zhai et al. 2019). In that species, only the antennae are differentiated from the rest of the appendages, which has the double advantage of (1) not making crazy hypotheses about limb specialization in Gladioscutum and (2) giving me fewer different types of limbs to sculpt.

Like Gladioscutum, most bradoriids are only known from their decay-resistant valves, which are often squashed flat in a so-called "butterfly" position. This arrangement has been traditionally interpreted as the life position of the animals, which were implied to crawl over the seafloor like tiny crabs (e.g., Hou et al. 1996). Yet, undistorted fossils of head shields preserved in 3D are almost always closely drawn together, which is similar to the way modern bivalved arthropods like ostracods are articulated (protecting the soft limbs and body) and probably more reflective of the actual life position of bradoriids (Betts et al. 2016), as depicted here.

References:

Betts, M. J., Brock, G. A., & Paterson, J. R. (2016). Butterflies of the Cambrian benthos? Shield position in bradoriid arthropods. Lethaia, 49(4), 478–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/let.12160

Hinz-Schallreuter, I., & Jones, P. J. (1994). Gladioscutum lauriei n.gen. N.sp. (Archaeocopida) from the Middle Cambrian of the Georgina Basin, central Australia. Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 68(3), 361–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02991349

Hou, X., Siveter, D. J., Williams, M., Walossek, D., & Bergström, J. (1997). Appendages of the arthropod Kunmingella from the early Cambrian of China: Its bearing on the systematic position of the Bradoriida and the fossil record of the Ostracoda. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 351(1344), 1131–1145. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1996.0098

Hou, X., Siveter, D. J., Williams, M., & Xiang-hong, F. (2001). A monograph of the Bradoriid arthropods from the Lower Cambrian of SW China. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of The Royal Society of Edinburgh, 92(3), 347–409. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263593300000286

Zhai, D., Williams, M., Siveter, D. J., Harvey, T. H. P., Sansom, R. S., Gabbott, S. E., Siveter, D. J., Ma, X., Zhou, R., Liu, Y., & Hou, X. (2019). Variation in appendages in early Cambrian bradoriids reveals a wide range of body plans in stem-euarthropods. Communications Biology, 2(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-019-0573-5

Zhang, H., Dong, X., & Xiao, S. (2014). New Bivalved Arthropods from the Cambrian (Series 3, Drumian Stage) of Western Hunan, South China. Acta Geologica Sinica - English Edition, 88(5), 1388–1396. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-6724.12306

#i'll probably make more art of cambrian bivalved arthropods with fucked up spines#because there is no shortage of them#and they still manage to all look rather distinct#gladioscutum#bradoriid#(?)#arthropod#cambrian#paleozoic#australia#paleontology#palaeoblr#paleoart#my art

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #59: Stem-Crustacea – Actual Ancient Aliens & Bivalved Buddies

The majority of known fossils of Cambrian crustaceans are in the form of minuscule microfossils with "Orsten-type preservation" – formed in oxygen-poor seafloor mud and exceptionally well-preserved in three-dimensional detail. They can only be discovered and studied after dissolving away the rock around them with acid and picking through the residue under a microscope, then they're scanned with an electron microscope to see their fine details.

And it turns out some of these tiny early crustaceans looked really weird.

Cambropachycope clarksoni is known from a small number of specimens from the Swedish Orsten Lagerstätte (~497 million years ago). And at first this stem-crustacean seems like it's easily one of the most bizarre of all Cambrian animals, looking more like a speculative alien creature design (or possibly a pokémon) than a real once-living animal.

Up to 1.5mm long (0.06"), it had a large pointed "head" bearing a single huge compound eye with up to 150 facets. Its long tapering body had one pair of simple appendages at the front, then three pairs of biramous appendages, and then four more pairs of paddle-like appendages that decreased in size further back.

…But its strange anatomy starts to make a little bit more sense once you figure out what's actually going on: that's not a head.

The "head" is actually just an eyestalk with a pointy projection on the back. Cambropachycope's actual head encompasses the first third or so of its body, with the first appendages being antennae and its mouth located on its underside just behind them. The next three pairs of biramous limbs are other head appendages – probably corresponding to the second antennae, mandibles, and maxilluae of other pancrustaceans – and then the "paddles" are its thorax limbs.

With its huge cycloptic eye and swimming paddles it was probably an active predator preying on smaller planktonic animals, possibly convergently similar to some modern predatory water fleas.

A second very similar-looking stem-crustacean was also found in the same deposits – Goticaris longispinosa – hinting that there may have been an entire weird lineage of these little alien swimmers in the late Cambrian oceans, which the Orsten fossils are only giving us the smallest glimpse at.

———

Meanwhile some of the most abundant animals in Orsten deposits are the phosphatocopids, with around 30 different species known from between about 518 and 490 million years ago.

These tiny arthropods were less than 1cm long (0.4") and had bivalved carapaces completely covering their bodies. They're mostly known just from their empty shells, but some specimens do preserve the rest of them, mostly represented by various early larval stages with the exact anatomy of later larvae and adults being less well understood.

They were traditionally regarded as being true crustaceans and part of the ostracods, and sometimes were lumped together with various other similar Cambrian bivalved groups like the isoxyids and bradoriids – but the similarities between them seem to have been superficial and convergent. More recently phosphatocopids have been considered to be stem-crustaceans instead, very closely related to the true crustaceans but not quite part of that lineage.

Klausmuelleria salopiensis is one of the earliest known phosphatocopids, found in the Comley Limestone deposits in England (~511 million years ago). Just 340μm long (~0.01") it's only known only from a single very early larval stage – often referred to as a "head larva" because it's essentially just a swimming head, with all four of its pairs of appendages corresponding to the head region of older individuals.

Like other phosphatocopids it would have lived just above the seafloor in oxygen-poor waters, and probably mostly fed on suspended particles of organic detritus. Some species had particularly strong spiny gnathobases at the bases of their appendages, however, suggesting they may have also been crushing and manipulating harder food items, possibly "micro-scavenging" on dead small planktonic animals.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#cambropachycope#klausmuelleria#phosphatocopida#stem-crustacean#pancrustacea#mandibulata#euarthropoda#arthropod#panarthropoda#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art#actual ancient aliens#larva

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

X-ray analysis reveals amazing 3-D soft anatomy of animals that lived 500 million years ago

https://sciencespies.com/biology/x-ray-analysis-reveals-amazing-3-d-soft-anatomy-of-animals-that-lived-500-million-years-ago/

X-ray analysis reveals amazing 3-D soft anatomy of animals that lived 500 million years ago

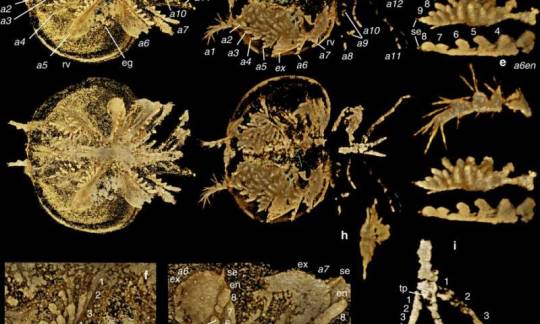

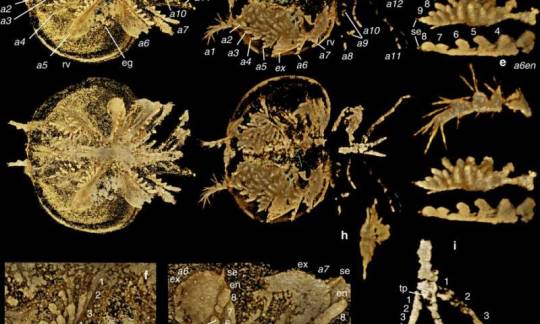

Kunmingella douvillei (Mansuy, 1912): a, f, g (YKLP 16235); b–e, h, i (YKLP 16233). All views are ventral. a–e, h Stereo-pairs with a 20° tilt. a, b Whole animal views: in a, eggs can be seen mid-valve, nestled in the region of the lobal structure; in b, the green coloured elongate structures appear to be organic but are not part of the bradoriid. c Right appendage 1. d Endopod of right appendage 5 (incomplete proximal part). e Endopod of right appendage 6 (proximal podomeres not shown). f Right appendage 5. g Left mid and some posterior trunk appendages. h Possible neural structures. i Posterior-most part of the trunk and limbs. Scale bar: a 2.19 mm; b 1.65 mm; c 560 µm; d 850 µm; e 610 µm; f 820 µm; g 730 µm.; h 680 µm; i 810 µm. a1–a12 1st to 12th appendage (italic signifies a right-side appendage), eg egg(s), en endopod, ex exopod, se seta(e), tp tailpiece, numbers 1–9 refer to the podomeres and/or endites, from distal to proximal From: Variation in appendages in early Cambrian bradoriids reveals a wide range of body plans in stem-euarthropods

An international team led by scientists from the University of Leicester and Yunnan University in China has revealed unprecedented anatomical detail from fossil animals that lived 500 million years ago.

The team used X-ray analysis to penetrate rocks, revealing ancient bodies, eyes, legs, and even the hairs on the legs of the animals.

In one case, the X-ray analysis even revealed an animal brooding a clutch of eggs, suggesting that males and females can also be discerned.

The fossils are from near the town of Chengjiang in Yunnan Province, South China, and were preserved in sedimentary rocks of an ancient shallow sea.

Dr. Tom Harvey from the University of Leicester said:

“The animals are arthropods, relatives of crabs and lobsters, with a segmented body. They look almost as though they were living a few moments ago.”

Dr. Dayou Zhai, lead author of the study at Yunnan University, said:

“We could see the tips of legs sticking out from below the animal’s hard exterior shell on the rock surface, but it was only with the X-ray analysis that we were able to peer inside the shell and find amazing soft-anatomy preserved.”

Prof Yu Liu, leader of the Chinese laboratory, said:

“These fossils are of profound importance for our understanding of early animal evolution, but rarely do we see this resolution of 3-dimensional detail preserved.”

Join us on Facebook or Twitter for a regular update.

Explore further

Ancient balloon-shaped animal fossil sheds light on Earth’s ancient seas

More information:

Dayou Zhai et al. Variation in appendages in early Cambrian bradoriids reveals a wide range of body plans in stem-euarthropods, Communications Biology (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-019-0573-5. Open Access: https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-019-0573-5

Provided by

University of Leicester

Citation:

X-ray analysis reveals amazing 3-D soft anatomy of animals that lived 500 million years ago (2019, September 4)

retrieved 4 September 2019

from https://phys.org/news/2019-09-x-ray-analysis-reveals-amazing-d.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

#Biology

0 notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #47: Bradoriida

The tiny bradoriids first turn up in the fossil record just before the earliest known trilobites, about 521 million years ago, and very quickly became some of the most abundant euarthropods in the mid-Cambrian. Found all around the world, they were clearly important components of many Cambrian food webs and probably had varying lifestyles from species to species, ranging from living on the seafloor to actively swimming around in the water column.

Less than 2cm long (0.8"), they're mostly known just from fossils of their bivalved carapaces, but some specimens preserve evidence of a pair of antenna and varying arrangements of biramous and uniramous limbs.

They were traditionally thought to be crustaceans closely related to ostracods, but some studies have instead shifted them towards being considered stem-crustaceans or stem-mandibulates instead. And more recently rare high-detail preservation of the soft anatomy of a few species have suggested they actually belong even further down the arthropod evolutionary tree, as "higher stem" euarthropods positioned between the megacheirans and the earliest actual euarthropods.

Kunmingella douvillei is one of the best-known bradoriids, with its fossils being incredibly abundant in the the Chinese Chengjiang fossil deposits (~518 million years ago). About 5mm long (0.2"), it had two different types of biramous limbs and a couple of pairs of uniramous limbs at the back.

Some female specimens have been found preserved with eggs, carrying up to 80 on their rear biramous limbs, representing some of the oldest evidence of brood care in the fossil record.

After their initial success the bradoriids gradually declined through the late Cambrian, but a few species persisted into the Ordovician and they finally went extinct sometime around the middle of that period – which was also around the time that the ostracod crustaceans began to appear and diversify.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#kunmingella#bradoriida#euarthropoda#arthropod#panarthropoda#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art

104 notes

·

View notes