#cha: kobus

Text

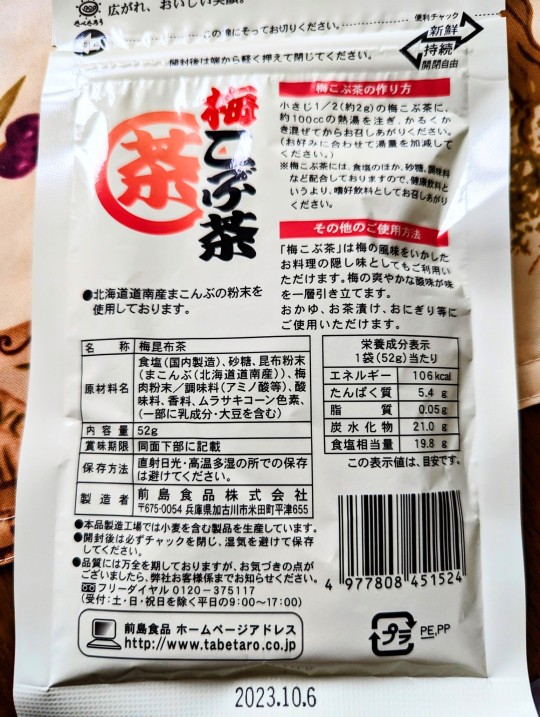

So guys, did you know about Google lens?? That it can translate text in an image?! I just discovered this function on my phone the other day, and I was able to "read" a package that was in Japanese!

Here's the package. I can read hiragana and katakana but I suck at kanji. I know the last kanji is "cha" (tea), and the hiragana says "kobu", but I didn't know what "kobucha" is.

I knew it was some sort of beverage powder. I wasn't sure if kobucha is the same thing as kombucha.

Here's the back:

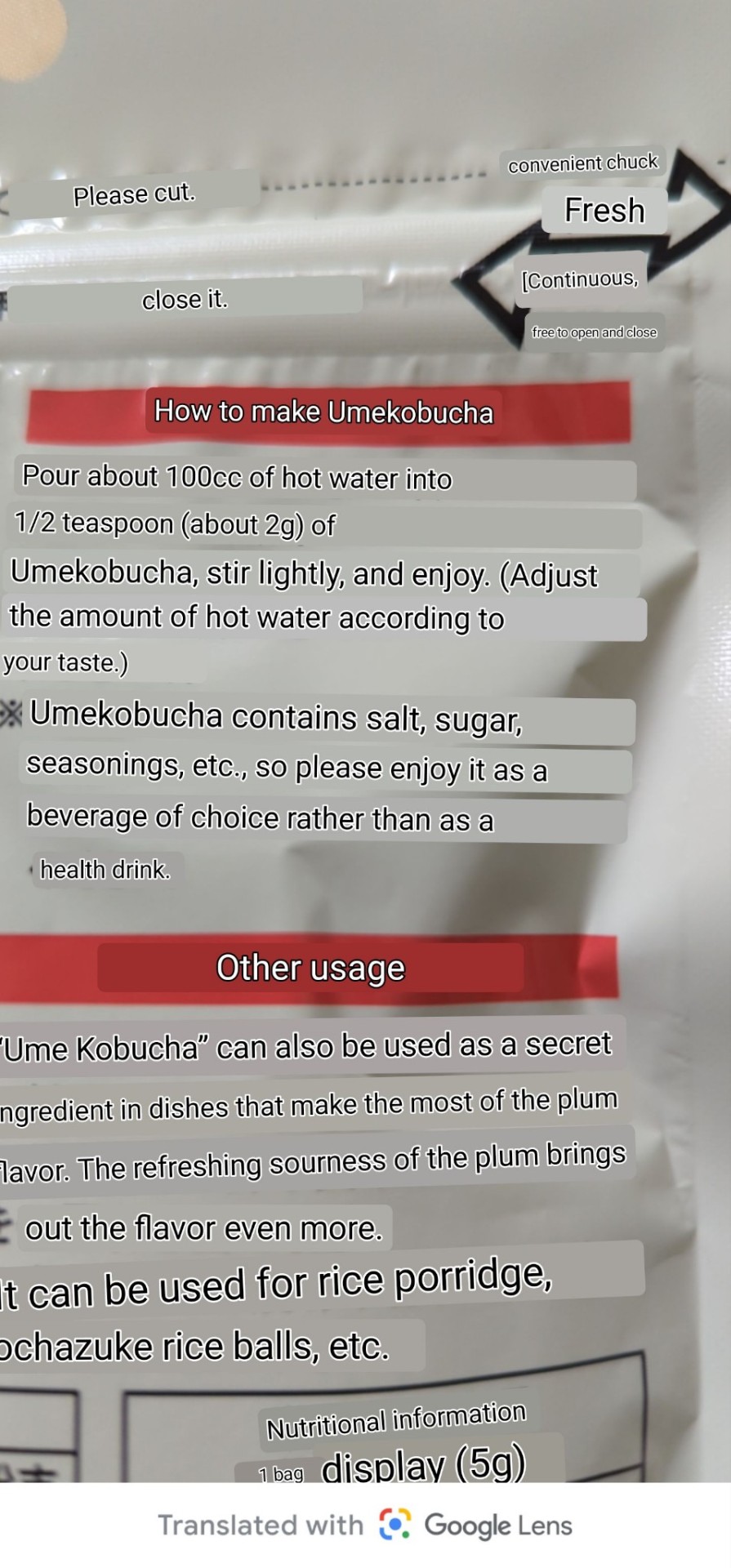

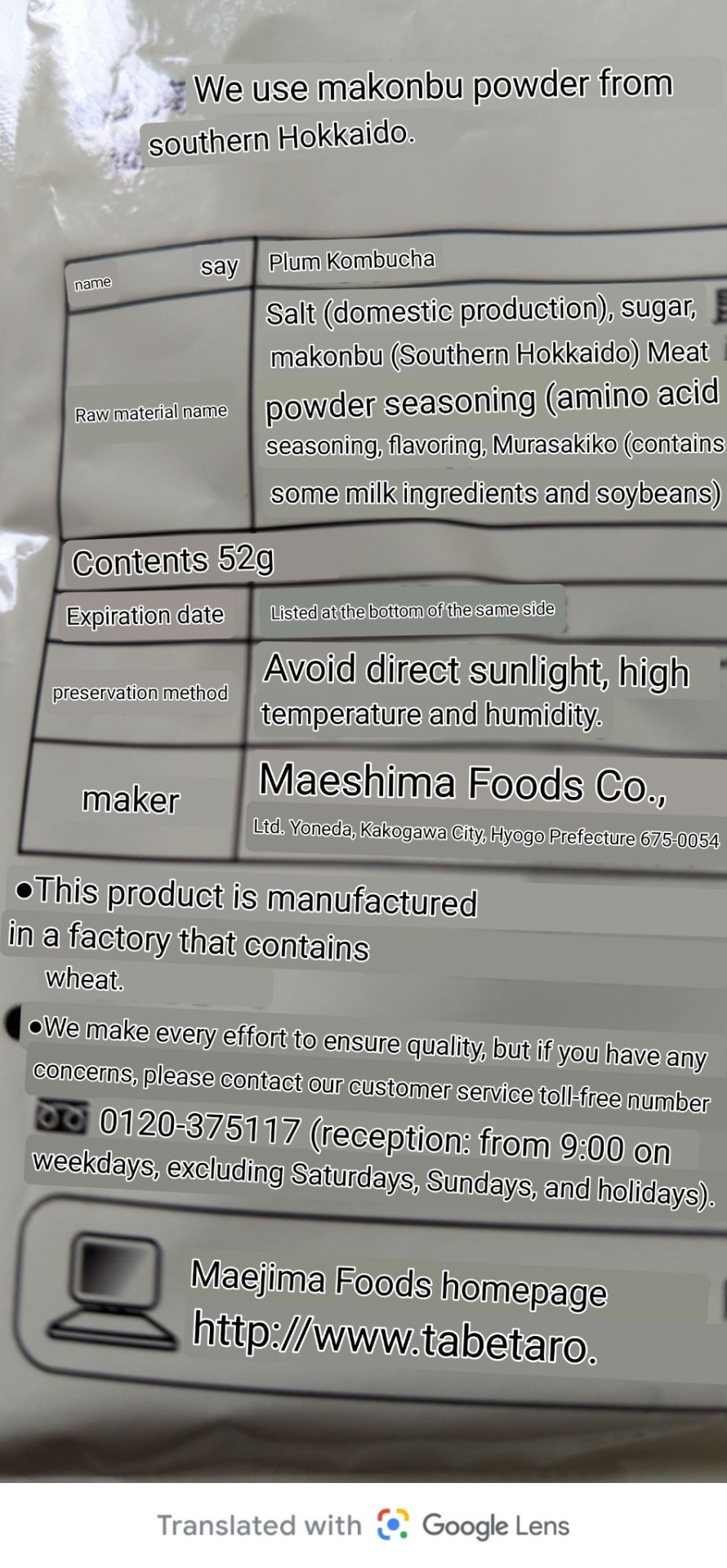

Do I just add water? Does it need to ferment, or what? No idea. Then I found out I can do this:

Isn't that wild?? This is sooo great! I have so many things I can't read, and now I will be able to!

So, in case you are having a hard time reading the translated image, this is "umekobucha". Ume is plum, and kobucha is kombucha (a fermented drink made of kelp). I've never actually had kombucha before, even though it seems to be all the rage and is available everywhere. Fermented kelp doesn't sound too appealing to me, but I'm willing to give umekobucha a try.

#japanese language#japanese#japan#google lens#translator#translation#umekobucha#kombucha#ume#japanese plum#kanji#梅コブ茶

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

UNPROMPTED STARTER » @firexflower — 𝕥𝕤𝕦𝕓𝕒𝕜𝕚 𝕘𝕖𝕥𝕤 𝕒𝕥𝕥𝕖𝕟𝕥𝕚𝕠𝕟-𝕖𝕕 𝕓𝕪 𝕒 𝕕𝕖𝕝𝕚𝕟𝕢𝕦𝕖𝕟𝕥 𝕓𝕠𝕪.

“Hey, Ootani... do you want any tea?” Now that she was officially a guest in his apartment, Akira figured he should make her stay as comfortable as possible. Why, even if he didn’t have much to really offer Tsubaki in terms of sweets, he should still have some of that kobu-cha tea Aunt Natsumi had given him lying around, so he could at least make both of them a hot beverage.

#firexflower#█ ▓『 ✦ ⸂ •• STARTER — ⧼ closed. ⧽ 』#█ ▓『 ✦ ⸂ •• QUEUED — ⧼ because livi is a busy adult irl. ⧽ 』#█ ▓『 ✦ ⸂ •• THREAD — ⧼ 05: firexflower / akira and tsubaki. ⧽ 』#┕━ ❛ ☣. muse »» 𝗔𝗞𝗜𝗥𝗔 𝗞𝗜𝗝𝗜𝗠𝗔〡it’s not that i don’t like people. i’m just more comfortable when i’m by myself.#┕━ ❛ ☣. post NG »» 𝗔𝗞𝗜𝗥𝗔〡being able to waste time doing nothing makes me realize my daily life is back to how it used to be.#[ sorry this took so long! work made me busy... and i kept hyperfixating over my caligula boys ]#[ to the point where i had forgotten i even owed you a starter otl ]

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

kobus 22, parch 37

22. when they speak, do they have a default tone of voice? if yes, do they try to change it? why?

Kobus' tone of voice at base is very dry. It's not indicative of their feelings, he just has to deal with spirits often enough that where it's not helpful to use normal ideas of "tone", even with Mina, but around humans they do put in an effort to snap out of that some, if he remembers.

37. How do they pass time on a train?

Work! That is to say, looks up reviews of pizza places and creates his frankensteined review, before submitting it to his boss. It's a lucrative position.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

cerise 6, 7, 9, 10, 20. arcis 6, 7, 9, 10, 24. nova 34, 35 <3

haha hiiiiiiii meg

under the cut bc there's a million

cerise

6. what quality do they like the most about themselves?

her own resilience, both in the sense of 44 hit points when most people she knows have 10 and in that she knows most people couldn't survive two and a half months in rhest and come out as functional as she is. i think this was something that was true even before Rhest--she's always considered herself a resilient person and i think on the first night in Rhest once she'd gotten over the initial overwhelming shock of it all and begun to process where she was and what was happening she grounded herself and went "i am going to survive this. somehow i'm going to survive this." and then she did! :]

7. what quality do they like the least about themselves?

she hates the fact that her fear response is to freeze :[ it's why she was frustrated with herself after freezing up in the surgery room in the cathedral--she can't afford to be paralyzed in a dangerous situation! but she waited too long for the right time to get out of rhest and had to leave calista behind, she let the mage carve all the way through her arm before thunderstepping out, she was so ineffective when she fought the mage, she lost a round to dragon fear the first time she saw it, she noticed something was Off about the guard who turned out to be esme and didn't do anything until too late, she sat still for the whole hostage situation...she doesn't Act when she's afraid! and she hates that!

9. who do they admire? why?

she admires a lot of people! she admires Fásach’s kindness and consistency. she admires the connection Auberon has with things others overlook. she really admires Camille’s courage and boldness and resilient optimism, and Kobus’s grounded sincerity and competence. and she really admires the way Sico can get anyone to do what he wants! she admires her sorcerers and how resilient they are. she admires what Papaye is doing, but that one’s...complicated. she admires Ash’s kindness, and Priya’s intelligence, and Esme’s cleverness, and Maximo’s talent with magic, and then, well, oh BOY does she admire Petal more than maybe anyone else,

10. who do they hate? why?

the high priest. every single guard and priest who was at rhest. every single person who knew about rhest and did nothing to stop it (an abstract concept, and so far the two people she has met who fit this description she ended up NOT hating, but it's on the list <3). the masked mage, hate in the present tense even though they’re dead.

20. describe one of your favourite rp moments with this character

the conversation in Papaye's carriage! balancing the insane mix of emotions that was learning about her village but also about Papaye's allegiances and having to figure out on the fly how cerise wanted to present herself and what, if anything, she could do to help was just SO much fun...I loooove when she gets to be really 18 cha 16 int about things it's so fun to write

arcis

6. what quality do they like the most about themselves?

her mind! sharp, reliable, good at putting pieces together and at recalling things accurately and at knowing how she can shape those things into what she needs them to be.

7. what quality do they like the least about themselves?

she’s Frustrated by how she can’t quite connect with people. that’s part of what that one conversation with Elio was about--people are a useful resource! she should be able to make friends. that would be Useful To Her Goals. as it is she's very forceful, and can hold her own in a diplomatic negotiation, but casual conversation is NOT it, which is a weakness that she doesn't like that she has. depending on how intense we end up getting with the politics side of this game she might have Character Development in this area, we’ll see

9. who do they admire? why?

other wizards!!!! also she admires the psionicists who blew the weeping city wide open, and she will admire uoser if he’s actually able to achieve his goals. her feelings on her party members haven’t reached admiration, but they could certainly get there, especially with Elio. also she. sob. she kind of admires these sentient zombie rats for being something new and unexpected and seizing control of their own minds,

10. who do they hate? why?

...huh. there’s gotta be SOMEONE but i SURE am drawing a blank. she doesn’t like people who can’t put their money where their mouth is, but “hatred” feels less accurate than like, “disdain.” i think she WOULD hate someone whose incompetence endangered others, especially herself or her allies.

24. are they good at keeping secrets? does it depend on how big the secret is?

nova

yes and yes <3

34. pick a character that they know. what is something that they do that your character finds charming/endearing?

nova finds it charming and endearing that legs is a little frog :) this is a joke but also i mean it! nova has this childlike wonder quality to them--they know what a frog is, they could describe one to you, tell you several species and which are poisonous and how various cultures view them, but the first time they held a frog in their hands and felt its feet on their palm and heard its ribbit for themselves that was a brand new sensation!!

35. pick a character that they know. what is something that they do that your character finds annoying/frustrating?

I don't know my party members well enough for this yet but Nova is more "We Will Help Every Person Who Needs Help" than most of my characters so if any of the others aren't down for that that's probably a source of frustration and tension

#as usual you REALLY know how to pick em. almost cried writing out the first one for cerise#and the answer to the second one is part of why auberon and camille's reaction to the floaroma plan stung SO much#and why she was so desperate to get them to see her point. she wasn't freezing this time! she took the deal rather than ask for time#to think about it which was her first instinct! but god if she turns out to be WRONG--#and you'll notice she sure doesn't hate the god queen <3#cha:cerise#cha:arcis#cha:nova#ask game

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (2): (1586) Tenth Month, First Day, Go-atomi [御跡見].

2) The same day¹.

Things were left [exactly] as they were [when Hideyoshi departed]².

◦ [Guests³:] Bizen-saishō [備前宰相]⁴, Sōmu [宗無]⁵, Sōkei [宗惠]⁶.

◦ The room was the same⁷.

﹆ Toko: the flower arrangement [by Toyotomi Hideyoshi] was left as it was⁸.

◦ On the shelf, the remainder of the tea, [in] the Shiri-bukura, on its tray⁹.

﹆ When [the guests] entered the room, everything remained as it had been¹⁰; the kama was lifted up so that [the new guests] could have a look at the remains of the charcoal [that had been arranged by Hideyoshi]¹¹.

◦ And again, a little more [charcoal] was added, and the kama returned [to the ro]¹².

▵ Kashi ・ senbei [センヘイ], kobu aburite [コフ アブリテ]¹³.

Go [後]¹⁴.

Kurete [暮テ]¹⁵.

◦ Toko: after [Hideyoshi's] flower [arrangement] was taken away¹⁶, a tōdai [燈臺]¹⁷ [was hung up in its place].

﹆ The Shiri-bukura was lowered [to the mat]¹⁸.

◦ Mizusashi: the same as before¹⁹.

◦ On the shelf: the habōki²⁰.

◦ Chawan: as before²¹.

Everything else was the same [as earlier in the day]²².

_________________________

¹Onaji hi [同日].

This means “the same day.”

It was the first day of the Tenth Lunar Month of Tenshō 14 [天正十四年] (1586).

²Go-ato ni sono-mama [御跡ニ其儘].

Go-ato [御跡]: go [御] is an honorific (it indicates that someone important did something*); ato [跡] literally means footprints. In other words, everything was left exactly as it was when Hideyoshi left the room†.

Sono-mama [其儘] means "as it is;" "as one finds it;" "as (things) stand."

__________

*In this case, it was what remained (in the room) after Hideyoshi took his leave.

†In this kind of construction, ato refers to the (intact) setting (just recently) vacated by an important personage -- i.e., Hideyoshi.

³In this kaiki, the names of the guests are simply listed without being introduced by the word “guests.”

⁴Bizen-saishō [備前宰相].

This refers to the daimyō and nobleman Ukita Hideie [宇喜多秀家; 1572 ~ 1655], who, in addition to being the lord of Bizen [備前] and Mimasaka [美作] provinces*, served as an Imperial Chamberlain (jijū [侍従]), Imperial Councillor (sangi [参議]), lieutenant-general of the Left Imperial Guards (sa-konoe ken-chūjō [左近衛権中将]), and provisional Vice-councilor of State (gon-chūnagon [権中納言]), ultimately attaining the second grade of the Third Rank (ju-sanmi [従三位]†.

Hideie also was a member of Hideyoshi’s Council of Five Elders (go-tairō [五大老]), which was created to act as the regent for Toyotomi Hideyori after his father’s death, and opposed Tokugawa Ieyasu at the battle of Sekigahara, for which he was exiled to Hachijō-jima [八丈島], an island in the Philippine Sea far distant from the Japanese archipelago.

The sobriquet Bizen-saishō [備前宰相], which means something like “Chancellor of Bizen,” was Ukita Hideie’s nickname, due to his huge influence over the affairs of this province.

___________

*Both provinces form part of modern-day Okayama Prefecture. The village of Imbe [伊部], which is in Bizen, is the original home of Bizen-yaki.

†Though at the time of this chakai, Hideie was of course not such a high noble. His father, Ukita Naoie [宇喜多直家; 1529 ~ 1581], the hereditary lord of Bizen, had died several years before, and Hideie was elevated to a prominent position several months later at the very young age of 10, by the Oriental way of counting. (At the time of this chakai, Hideie was just 15 years of age according to the same way of counting ones age where the person is assigned the age of “one” at birth.)

Hideie was subsequently adopted by Toyotomi Hideyoshi after he married Hideyoshi’s adopted daughter Gōhime [豪姫; 1574 ~ 1634 -- whose birth-father was the great lord Maeda Toshiie], and it may have been for some such reason that Hideyoshi invited him to attend this atomi (and possibly was the reason why Hideyoshi deigned to arrange the charcoal before serving usucha to his two attendants and Rikyū -- to impress the young man with the importance of mastering chanoyu as his soon-to-be-adoptive-father had done).

It might be doubted whether Hideie was actually known as Bizen-saishō at the time when this chakai took place (since he would have only just celebrated his gempuku [元服], or ceremony of attaining manhood, earlier in the year). The use of this sobriquet, then, might represent a later emendation (perhaps intended to clarify the identity of the guest, and so associate him with the person thus named in the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki).

⁵Sōmu [宗無].

This refers to Okayama Hisanaga [山岡 久永; 1534 ~ 1603*], who is also known as Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu [住吉屋宗無]†. He was a wealthy townsman from Sakai, and also a highly respected chajin‡, and served as one of Hideyoshi’s Eight Masters of Tea (sadō hachi-nin-shū [茶頭八人衆]).

Sōmu’s presence as the ji-kyaku was very likely intentional (perhaps at Hideyoshi’s direction)**, so that he could assist Hideie (who, at his young age, probably did not know much about chanoyu††).

___________

*Certain accounts suggest that Sōmu may have died in 1595, at the time when Sakai was razed on Hideyoshi’s orders (as a punishment for the city-state’s opposition to his invasion of the continent).

†He is identified in this way in the other versions of the Hyakkai Ki.

‡Sōmu is said to have first studied chanoyu under Jōō, and then later with Rikyū (though, given his high standing with both Nobunaga and Hideyoshi, this latter assertion might be a revisionist opinion popularized by the Sen family during the Edo period).

He studied Zen under Shunoku Sōen oshō [春屋宗園和尚; ? ~ 1611], from whom he received the name Sōmu [宗無] -- which he used as his professional name later in life.

**In the Hyakkai Ki, Sōmu frequently appears in a role that might be interpreted as being Rikyū's assistant, in situations where the shōkyaku either was inexperienced, or his rank indicated that he needed to be treated with especial deference (in such a case, Sōmu would convey the chawan to him, for example, and then return it to the host after the shokayku had finished drinking).

††Since only usucha would have been served at this atomi, this may have been Hideie's first experience of chanoyu. Thus the atomi is being staged as a sort of miniature chakai.

⁶Sōkei [宗惠].

This refers to Mizuochi Sōkei [水落宗惠; dates of birth and death unknown], who was another respected machi-shū chajin from Sakai*. He is also said to have been the father of Rikyū's son-in-law, Sen no Jōji [千 紹二]†.

__________

*Some suggest that he was also one of Rikyū's disciples (though it is more likely that he was a member of the group that formed around Rikyū in the years after Jōō’s death -- given Sōkei’s contemporary reputation as a chajin).

†Sōkei's son is usually known as Sen no Jōji because Rikyū adopted him into the Sen family upon his marriage to Rikyū's daughter (Rikyū having only one biological son -- which, for a merchant, was akin to putting all of ones eggs in one basket).

⁷Onaji zashiki [同座敷].

Literally, the same sitting-room.

This refers to the 2-mat room which Rikyū used during the chakai for Hideyoshi (that had just concluded).

⁸Toko ・ go-hana sono-mama [床 ・ 御花其マヽ].

Go-hana [御花]: the use of the honorific (go [御]) means that Rikyū is referring specifically to the chabana created by Hideyoshi (which Rikyū moved from the floor of the toko to the hook attached to its rear wall). Hideyoshi's chabana (white chrysanthemums in an Arima-kago [有馬籠] -- this basket is shown below) was left as it was.

The Shigaraki hanaire and usu-ita would have been removed from the toko after Hideyoshi left.

⁹Tana ni go-cha no nokori, Shiri-bukura ・ bon ni [棚ニ御茶ノ殘、尻フクラ・盆ニ].

Go-cha no nokori [御茶の殘り]: the use of the honorific (go [御]) indicates that this was the matcha remaining from what had been used to serve Hideyoshi.

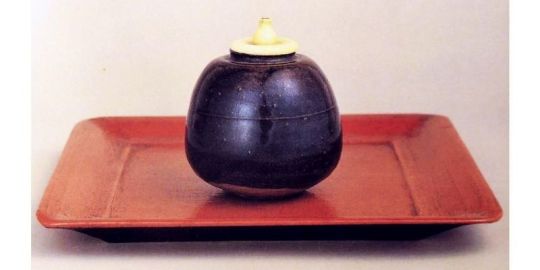

As was mentioned before, the Shiri-bukura [尻膨] was Rikyū’s most prized chaire; and it was from contemplating this bon-chaire that his unique ideas about how to perform the bon-date temae arose*.

Because reused tea could only be served as usucha, Rikyū is also suggesting that koicha was not served to Hideie and the others (as was sometimes done in other atomi no chakai).

___________

*This was perhaps the greatest difference between Rikyū’s chanoyu and that of Jōō (who created the bon-date temae). Oddly (considering the over-blown lip service that they accord to Rikyū), none of the modern schools perform bon-date in his way: all of them prefer to do this temae the way Jōō did it (even though most of the modern schools prefer to use the smaller “Rikyū-sized” chaire-bon, rather than the larger trays -- now almost always used as higashi-bon -- that were employed by Jōō and his disciples).

¹⁰Za-iri sono mama [座入其マヽ].

This means that when the guests entered the room for the (abbreviated) sho-za of this atomi no chakai, the ro was left exactly as it had been when Hideyoshi departed. This was important, since the idea was to allow the guests to inspect the charcoal laid* by Hideyoshi.

__________

*Actually, Hideyoshi had simply repaired the fire that had been laid by Rikyū. Nevertheless, the condition of the different pieces of charcoal would make this obvious to someone who understood chanoyu; while simply impressing the importance of mastering chanoyu to the young man who was nominally the shōkyaku at this atomi. (This atomi seems to be attended by mock formality, which in turn suggests that this may have been Hideie's first experience of chanoyu.)

¹¹Kama agete go-sumi no nagori ikken [釜アケテ御炭ノ名殘一覧].

Ageru [上げる] means to raise something up; lift something up; bring something up. The kama was lifted out of the ro (and presumably stood on a kamashiki that was placed on the left side of the utensil mat*). This allowed the guests to have an unobstructed view of the interior of the ro.

Go-sumi [御炭]: once again, the use of the honorific indicates that this refers to the charocoal arranged (or repaired) by Hideyoshi.

Nagori [名殘] means, remains, remnants, vestiges. Since the time of Jōō it had been said that the host's skill could be ascertained by the remains of his arrangement of the charcoal (since the vestiges of the fire showed not only the arrangement, but the manner in which the fire had taken hold, and burned down -- things that were just as important as the beauty of the arrangement itself).

Ikken [一覧] means to glance at something; to have a look at something.

___________

*I have seen a commentary that suggested that the kama was left suspended on a chain several shaku above the mouth of the ro, so that the guests could look at the fire underneath.

However, given the size and weight of Jōō‘s ito-me kama [絲目釜] (shown above), this would have been ill-advised (since it would look very dangerous to the guests, even if the chain and ceiling were actually strong enough to support it).

This interpretation was probably the result of the result of the commentator (who was not a practitioner of chanoyu) misunderstanding the word kakuru [掛くる] -- see the next footnote.

¹²Mata sukoshi oki-soe, kama kakuru [又少置添、釜カクル].

Oki-soeru [置き添える] means to place something beside (something else); add one thing to another. The new pieces of charcoal were placed next to the burning pieces, so that they would catch fire slowly (and so keep the kama boiling until the "gathering" was ended).

Kama kakuru [釜掛くる] literally means to hang or suspend the kama (over the ro). This expression originated in the old days, when the kama was suspended over the ro on a chain*. And it remained the way to express the idea of returning the kama to the ro even after the kama came to be placed on top of the gotoku.

This sentence is a good example of the way that Rikyū expressed himself. It is much closer to Korean syntax than Japanese (I was asked to point this kind of thing out by certain followers of this blog).

___________

*The expression is also used with regard to placing the kama on a furo. This may be an example of post hoc terminology; or the fact that the original furo was a kake-awase furo on which a kiri-kake kama was suspended -- here used because the kama rests on the ring-like mouth of the furo, with part of it hanging below the point of contact.

¹³Kashi ・ senbei, kobu aburite [菓子 ・ センヘイ、コフ アブリテ].

Senbei [煎餅] are rice crackers. They would have been procured from a specialty shop.

Kobu aburite [昆布 炙りて] means konbu (kelp) that has been toasted over a charcoal fire (rather than boiled in broth and tied into a bite-sized knot, which is the other way that it could be served as a kashi).

The kashi would have been served in a shallow vessel of some sort -- perhaps on a large dish, resting on an unpainted oshiki [折敷].

This kind of chakai, where only kashi are offered to the guests, is sometimes referred to as a kashi-kai [菓子會].

After eating their kashi, the guests would have gone out for a brief naka-dachi, while Rikyū readied the room for the service of tea.

¹⁴Go [後].

This indicates that what follows occurred during the go-za [後座], the second half of the chakai when tea is served.

¹⁵Kurete [暮テ].

Kureru [暮れる] means to become dark. The day is drawing to a close, and it is now dark enough outside that artificial illumination is needed within the room.

¹⁶Toko ・ go-hana tori-irete [床・御花取入テ].

Tori-irete [取り入れて] means to bring something in -- in this case, into the katte.

That is, the flowers arranged by Hideyoshi were removed from the tokonoma.

¹⁷Tōdai [燈臺].

This is a kake-tōdai. It is an L-shaped stand (sometimes made of wood and metal, and sometimes made from a piece of bamboo -- the two most common styles are shown in an Edo period sketch, below) that can be hung on the wall (in this case, from the hook attached to the back wall of the toko), which in turn supports a saucer of oil containing several burning wicks made of the pith of the lamp-rush plant (Juncus effusus var. decipens), called igusa [藺草] in Japanese.

Hanging the kake-tōdai in the toko (in place of the flower arrangement) is a practice called tō-ka [燈華] -- which is usually translated as “flower of the lamp” (though apparently without a clear understanding of what is intended, on the part of the translator).

This word is a pun (the homophonous tō-ka [燈火] is the “lamp-flame,” the source of the light); but hanging the tōdai in the toko, as a substitute for the chabana, was one of Jōō's most closely guarded secrets (and this is the reason why chabana were not displayed at night -- because the flame takes the place of the flowers).

¹⁸Shiri-bukura oroshite [尻フクラヲロシテ].

Orosu [下ろす]* means to lower something (in this case, from the shelf to the mat).

According to Rikyū's densho, precious utensils should not be placed on the shelf when it is dark (since the presence of candles on the floor will throw the things on the shelf into shadow, making it easier for the host to inadvertently knock them over when he goes to lower them to the mat).

Furthermore, the Shiri-bukura chaire now contains used tea (that will be served as usucha). Thus it is not appropriate for the tea container to be displayed on the shelf at the beginning of the service of tea.

The Shiri-bukura chaire, on its red Chinese tray, was placed on the mat, in front of the mizusashi.

___________

*Oroshite [下ろして] is, of course, past tense.

The Shiri-bukura chaire, on its tray, was lowered to the mat during the naka-dachi. It was already resting on the mat, in front of the mizusashi, when the guests entered the room for the go-za.

¹⁹Mizusashi ・ migi-dō [水指・右同].

As before, this was the aka-Raku yahazu-kuchi mizusashi [赤樂矢筈口水指] that had been made for Rikyū by Chōjirō.

²⁰Tana ni habōki [棚ニ羽箒].

This would have been the same go-sun-hane, made from the feathers of the shima-fukurō [島梟].

In Rikyū's temae, the habōki was used to dust the utensil mat at the end of the service of tea, as well as after the sumi-temae*.

Furthermore, it is a rule that, if there is a tana preset in the room, it should never be empty when the guests enter the room, or when they leave.

At the end of the temae, the hishaku and futaoki would be placed on the tana; and after dusting the utensil mat, the go-sun-hane would be removed from the room.

__________

*Neither of these things are usually done in the modern school’s temae.

When the utensil mat is a maru-jō [丸疊] -- a full-length tatami -- the habōki is used to dust only the upper end of the utensil mat (which is equivalent in size to a daime).

After sliding out of the katte-guchi, the host turns around and leans back into the room, and cleans the lower 1-shaku 5-sun of the mat with a za-baki [座掃], a large feather broom (usually made from the pinions of a large bird, such as an eagle, such as shown above) that is used for cleaning the room in general.

²¹Chawan ・ migi-dō [茶碗・右同].

This was the Wari-kōdai [割り高臺] chawan, a very old Korean bowl that had been brought to Japan by one of the refugees escaping the Ming military invasion of Korea in the mid-fifteenth century.

²²Sono-hoka nanimo mina onaji [其外何モ皆同].

Everything else was the same (as during the earlier chakai).

This means that all of the other utensils* that have not been mentioned above were the same.

But it also means that things were done in the same way as earlier* -- in other words, the chawan (with chakin, chasen, and chashaku arranged in it) was placed inside a (new) mentsū [面桶]†, and so everything not already displayed in the room was brought out at one time.

___________

*In other words, the kōgō would have been his ruri-suzume [瑠璃雀].

And Rikyū would have used an ori-tame [折撓] that he had made himself, as his chashaku.

While the futaoki would have been a take-wa [竹〇], as was almost always the case at Rikyū’s wabi chakai.

As earlier in the day, the hishaku would probably have been resting on the futaoki, on the left side of the mizusashi, with its handle parallel to the left heri of the mat.

†The only exception to which was that only usucha would be served during this atomi no chakai. Both because tea that had already been used to serve koicha at an earlier chakai could never be used to serve koicha at a subsequent gathering.

But also because, if this were Hideie’s first experience of chanoyu, he would probably not like koicha -- which is an acquired taste: the host must always consider the shōkyaku when deciding what he is going to do.

‡The mentsū [面桶] (above) should only be used one time, since absolute purity is its special feature. This is the reason why the chawan could be placed inside of the mentsū and so carried into the room -- something that would be unthinkable were the host using any other kind of koboshi (which could be used again and again).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nhìn lại hành trình thành tài gian nan của cậu bé “khác người thường” mới thấy niềm tin và tình yêu của cha mẹ có thể thay đổi tất cả

Bị phát hiện tự kỷ từ năm 3 tuổi, cậu bé David Barth vẫn phát triển tài năng và trở thành một họa sĩ nổi tiếng. Tuy nhiên, cách dạy dỗ và chia sẻ của cha mẹ cậu mới khiến nhiều người ngưỡng mộ.

Khi David Barth lên 3 tuổi, cha mẹ đã nhận thấy cậu bé có những hành động thật khác so với bạn bè cùng lứa. Cậu ấy không nói chuyện, không cười và không thích chơi với bạn bè. Lúc đầu bố mẹ David nghĩ đó là do con trai mình thấp còi, thiếu dinh dưỡng.

Tuy nhiên, thời gian trôi qua, các triệu chứng của cậu bé không những không giảm bớt mà còn nghiêm trọng hơn. "Điều này thật tồi tệ với gia đình tôi", bố mẹ David cho biết.

Khi vợ chồng nhà Barth đưa con trai đi kiểm tra, bác sĩ đã đưa ra chẩn đoán như sét đánh ngang tai: Cậu bé mắc hội chứng Asperger nghiêm trọng. Đây là một bệnh tâm thần hiếm gặp và thuộc về một dạng tự kỷ đặc biệt!

Nỗ lực của cha mẹ giúp con trai giải phóng nỗi sợ hãi, phát triển tài năng

Cha mẹ của David Barth rất sốc nhưng đã nhanh chóng chấp nhận sự thật này rồi họ cố gắng theo lời khuyên của bác sĩ để giúp con trai giải phóng nỗi sợ bên trong.

Mẹ của David, Inge Barth Wagemaker, lúc đó đang là một giáo viên giảng dạy gần nhà. Bà đã tham gia vào nhiều hội nhóm của phụ huynh có con mắc chứng tự kỷ nhằm tìm kiếm thông tin phục vụ việc chăm sóc, giáo dục cậu bé. Đặc biệt, bà dành rất nhiều thời gian ở bên con trai, cố gắng tìm cách giúp con hào hứng với một bộ môn hay lĩnh vực nào đó.

Ngẩn ngơ ngắm nhan sắc của thần đồng điển trai 9 tuổi bỏ học vì trường không cho tốt nghiệp sớm, IQ 145 sánh ngang Albert Einstein

David Barth (trái) và mẹ Inge Barth Wagemaker tại lễ khai mạc Triển lãm nghệ thuật thường niên lần thứ 5 của trẻ em mắc chứng tự kỷ tổ chức tại Bảo tàng nghệ thuật Inside-out của Bắc Kinh.

Thật may mắn, dường như cậu có phản ứng khác lạ với hội họa. Khi David Barth xem album, cậu sẽ liếc nhìn lâu hơn so với mọi thứ khác. Bà Inge đã không bỏ lỡ cơ hội, lập tức cho con trai thử sức với cây cọ vẽ. Ban đầu, cậu bé nguệch ngoạc một cách ngẫu nhiên, nhưng thành phẩm lại chi tiết một cách bất ngờ.

"Lúc đầu, chúng tôi nghĩ rằng David Barth chỉ bôi vẽ màu đơn giản, nhưng sau khi nhìn thấy tác phẩm của của con trai thì đã bị sốc", bố mẹ cậu bé cho biết.

David không chỉ có thể vẽ những con vật cậu bé đã thấy mà còn có thể thể hiện chúng một cách mới lạ, sinh động.

Đây là một bức vẽ bằng bút chì do David Barth tạo ra khi cậu bé 5 tuổi.

David có niềm đam mê đặc biệt với động vật. Cậu bé đôi khi vẽ ra những con ngựa, con bò… kỳ lạ, những con vật không thể tìm thấy trong thực tế. Tuy nhiên, cha mẹ cậu nhìn nhận quá trình vẽ của con trai đầy say mê và thích thú nên thở phào nhẹ nhõm. "Hãy để con cảm nhận thế giới theo cách của riêng mình, không tác động, không cố gắng thay đổi", bố mẹ David đã nghĩ.

Những bức tranh động vật sinh động của cậu bé mắc bệnh tự kỷ.

Cậu bé tự kỷ và tài hội họa khiến người người kinh ngạc

David nhận thức thế giới theo một cách độc đáo và có cái nhìn sâu sắc về sáng tạo nghệ thuật. Ngoài ra, cậu bé có sự chú ý đến từng chi tiết nhỏ, giúp định hình phong cách độc đáo của riêng mình.

Các tác phẩm của David Barth thường có bố cục tuyệt vời, màu sắc đẹp, độ chính xác và chi tiết đáng kinh ngạc. Tài năng thiên bẩm và phi thường này của cậu thường khiến người ta nhớ đến Stephen Wiltshire, một nghệ sĩ tự kỷ nổi tiếng thế giới người Anh, người rất thích vẽ những bức tranh chi tiết về cảnh quan thành phố từ trí nhớ.

Những bức vẽ động vật của David rất đáng chú ý. Trong bản vẽ "Chim" của mình, David đã mô tả 397 loài chim khác nhau. Cậu ấy còn biết rõ tên Latin cũng như thói quen sống của tất cả số động vật đó.

Bản vẽ này đã được đưa vào cuốn sách "Bản vẽ của trẻ tự kỷ" (năm 2009) của Mỹ cùng với tác phẩm của khoảng 50 nghệ sĩ tự kỷ khác từ khắp nơi trên thế giới.

Bản vẽ 397 loài chim của David được đưa vào cuốn sách cho trẻ tự kỷ.

Với sự giúp đỡ và khích lệ từ mẹ, họa sĩ nhí đã xuất bản cuốn sách ảnh đầu tiên vào năm 2008. Sau đó vào năm 2010, David đã sản xuất cuốn truyện tranh thứ hai của mình – "Wat is er toch gặp Kobus? (Chuyện gì xảy ra với Kobus?)". Cuốn sách kể về cuộc sống của một đứa trẻ tự kỷ theo cách hài hước và chứa nhiều thông tin cũng như lời khuyên hữu ích về cách nuôi dạy trẻ tự kỷ. David đã vẽ tất cả các hình minh họa và mẹ cậu ấy thì viết câu chuyện.

David đã có 5 triển lãm ở Hà Lan, lần đầu tiên được tổ chức vào năm 2004. Cậu cũng đã giành giải thưởng tại nhiều cuộc thi vẽ. Giải nhất của David đến từ một cuộc thi do Trường nghệ thuật Nga tổ chức năm 2005. Năm 2007, cậu tiếp tục giành được giải thưởng "Tài năng trẻ Caldenborgh" danh giá trong hạng mục "Truyện tranh". Ngoài ra, cậu bé cũng được mời thiết kế bìa album cho một ban nhạc nổi tiếng của Mỹ.

Những bức tranh của David được đánh giá cao về bố cục, màu sắc và các chi tiết.

Khi nói về tương lai của David, bố cậu nói: "David rất khó để học đại học và tìm một công việc bình thường như người bình thường. Nhưng chúng tôi không lo lắng nhiều về tương lai của con trai, vì David có thể tiếp tục phát triển kỹ năng vẽ, miễn sau con cảm thấy hạnh phúc".

Inge Barth Wagemaker cũng lạc quan cho biết: "David hài lòng với việc vẽ và cậu bé có tài năng. Tôi tin rằng cậu ấy có thể phát triển bản thân thành một nghệ sĩ, họa sĩ minh họa hoặc nhà thiết kế nghệ thuật".

Còn cậu bé tự kỷ David thì cho biết: "Khi tôi còn nhỏ, cha mẹ đã nuôi dưỡng khả năng nghệ thuật của tôi".

Rõ ràng, việc nuôi dạy một đứa trẻ là không đơn giản, đứa trẻ mắc bệnh lại càng khó khăn. Tuy nhiên, bằng tình yêu dành cho con trai, bố mẹ David Barth đã âm thầm hỗ trợ, động viên, giáo dục giúp cậu bé vượt qua bệnh tật và đạt thành công nhất định.

Theo Sina, China.org.cn

The post Nhìn lại hành trình thành tài gian nan của cậu bé “khác người thường” mới thấy niềm tin và tình yêu của cha mẹ có thể thay đổi tất cả appeared first on Việt Nam New - Tin tức nóng hổi trong nước và ngoài nước.

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2tOqOvD

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Người đàn ông phục vụ gần 100 geisha ở Kyoto

Những geisha luôn có một người phụ giúp trong việc mặc kimono hàng ngày, đó chính là các otokoshi.

Trước khi biểu diễn, geisha chỉ tự trang điểm, còn một người đàn ông sẽ giúp họ mặc kimono vì trang phục này có nhiều lớp dày và nặng, phần đai có thể dài tới 7,5 m. Những người đàn ông nhận nhiệm vụ này được gọi là otokoshi, họ là một hình tượng đặc biệt trong thế giới geisha và maiko (những cô gái tập sự thành geisha).

Geisha là những người có khả năng biểu diễn nghệ thuật tinh tế, thường đàn hát, nhảy và mua vui tại những bữa tiệc rượu của giới thượng lưu Nhật Bản. Hình ảnh quen thuộc của geisha là những cô gái trang điểm da mặt trắng sứ với lớp phấn dày, môi đỏ chúm chím và tóc búi cao trong trang phục kimono truyền thống. Ảnh: Pinterest.

Nhiếp ảnh gia Mỹ John Paul Foster có dịp tiếp xúc với Kojima-san, một otokoshi, trong thời gian ông làm việc ở Kyoto, Nhật Bản. Kojima-san là một trong 5 otokoshi làm việc tại quận Gion Kobu, phục vụ hơn 90 maiko và geiko (tên gọi của những geisha ở Kyoto). Công việc của họ đều là cha truyền con nối.

Kojima-san cho biết công việc của anh không chỉ giúp các geisha hay maiko mặc đồ hàng ngày. Trách nhiệm lớn nhất của những otokoshi là đảm bảo mọi phục trang của họ được đưa về nhà an toàn sau mỗi bữa tiệc hoặc buổi biểu diễn.

Kojima-san (phải) đi cùng một geiko. Ảnh: Pinterest.

Kojima-san đặc biệt bận rộn vào dịp nhà hát Gion Kobu Kaburenjo tổ chức điệu Miyako Odori, rất nhiều geisha sẽ tham dự. Anh có trách nhiệm đưa bất kỳ thứ gì các cô gái để quên hay đánh rơi tại nhà hát về.

Ảnh: Công việc thường nhật của otokoshi tại Kyoto

Kojima-san gặp nhiều khó khăn hơn mỗi khi phải làm việc với các geisha có thâm niên trong nghề, vì họ luôn có những yêu cầu đặc biệt. Ví dụ, Kojima-san sẽ phải biết đặt đai áo ở vị trí nào khi mặc kimono cho họ. Chỉ cần anh buộc lệch vài centimet, họ cũng sẽ biết và nhắc anh điều chỉnh.

Ngày erikae (khi các maiko trở thành geiko) không phải thời khắc nhiều cảm xúc với Kojima-san. Anh cho biết chỉ mất 5 phút để một otokoshi giúp một geiko hay maiko mặc quần áo nên giữa họ không có nhiều thời gian tương tác. Vào những dịp đặc biệt hơn, các otokoshi cũng chỉ cần 15 phút để chuẩn bị phục trang cho những cô gái.

Điều đáng buồn nhất mà Kojima-san chia sẻ chính là nhiều thay đổi lớn xảy ra tại quận Gion Kobu trong khoảng 20 năm trở lại đây, những quán trà không còn đông khách như trước. Điều này dấy lên nỗi lo cho tương lai của geiko, maiko và cả những người hỗ trợ họ. Kojima-san hy vọng rằng nét văn hóa này sẽ không bị mai một tại Nhật Bản.

Màn diễn của một geisha

Nguồn: http://ift.tt/2tCrpLN

0 notes

Text

Tee ist eines der ältesten Kulturgetränke der Welt. Schon vor 5000 Jahren wurden in China Teesträucher kultiviert. Buddhistische Mönche brachten

den gesunden Muntermacher schließlich im 9. Jahrhundert nach Japan, wo bis heute traditionell fast ausschließlich grüner, also unfermentierter Tee

getrunken wird. Eine Besonderheit ist der in Nippon sehr beliebte Matcha, der sich in hiesigen Landen immer größerer Beliebtheit erfreut.

Zwischen Granit zerrieben

Übersetzt bedeutet Matcha schlicht „gemahlener Tee“. Für seine Herstellung werden frisch geerntete Blätter gedämpft, anschließend mit Heißluft getrocknet und schließlich grobe Stiele und Rippen entfernt. Dann wird das zarte Blattgewebe mit Granitmühlen zu feinem, tiefgrünen Puder zerrieben. In seinem Ursprungsland ist Matcha dank seines intensiven Aromas vor allem eine beliebte Zutat für Leckereien wie Eiscreme, Macarons oder Schokolade, hat ursprünglich aber vor allem rituelle Bedeutung. So wird bei der traditionellen japanischen Teezeremonie, deren genauen Ablauf der bedeutende Teemeister Sen no Rikyu im 16. Jahrhundert festgelegt hat, stets diese spezielle Teevariante zubereitet. Dazu wird mit einem kleinen Baumbuslöffelchen, dem Cha-shaku, ein wenig Matcha-Pulver (ca. 1-2 g) in eine Teeschale aus Ton gegeben und mit heißem, aber nicht kochendem Wasser aufgegossen.

Diese meist in irdenen Farbtönen gehaltenen Schalen, die im ersten Moment oft wenig ansehnlich wirken – können ein Vermögen kosten, sofern

sie aus der Werkstatt eines berühmten Meisters stammen. Hinter ihrer vermeintlichen Unscheinbarkeit verbirgt sich in Wahrheit ein urjapanisches

Schönheitsideal: das Wabi-sabi. Dabei sollen kleine „Fehler“, im Fall der Teeschalen z. B. mithilfe der Glasur angedeutete Macken oder schiefe Ränder, den ästhetischen Genuss erhöhen. Sind sie doch ein Symbol dafür, dass nichts auf dieser Welt perfekt ist, sondern alles stetem Wandel unterliegt. Der aufgebrühte Matcha wird dann mit einem Chasen benannten Bambus-Besen kräftig aufgeschlagen, bis sich an der Oberfläche ein feiner, jadegrüner Schaum bildet. Je mehr desto besser. Am besten lässt man das Handgelenk dabei ganz locker und stellt sich vor, man würde mit Hilfe des Besens ein „M“ auf den Boden der Tasse schreiben. Mit ein bisschen Übung wird das schon. Anschließend genießt man das vollmundige Gebräu mit dem intensiven Umami-Geschmack in winzigen Schlucken.

Nichts für Ungeduldige

Ähnlich wie Bogenschießen oder Ikebana hat auch der sogenannte Cha-do oder Tee-Weg seinen Ursprung eigentlich im in Japan weit verbreiteten Zen-Buddhismus. Jeder Handgriff der Zeremonie ist bis ins kleinste Detail festgelegt. Nach dem Motto „Der Weg ist das Ziel“ dauert das ganze Prozedere mehrere Stunden – ist also nichts für Ungeduldige. Natürlich gelingt Matcha auch ohne Zen und schiefe Tassen in nur ein bis zwei Minuten und schon wenige Schlucke sorgen für einen heftigen Energiekick. Der Grund ist einfach: Anders als bei normalem Tee wird hier das Teeblatt

gleich mit verschluckt – nur eben fein pulverisiert. Und das enthält eine ansehnliche Dosis Koffein, denn traditionell wird der für Matcha verwendete

Grüntee etwa zwei bis vier Wochen vor der Ernte mithilfe von Netzen beschattet. Als Reaktion auf die verminderte Sonneneinstrahlung bildet die Pflanze nicht nur besonders viel Chlorophyll, verantwortlich für die intensiv grüne Farbe, sowie Aminosäuren, die für den vollmundigen Geschmack sorgen, sondern auch zusätzliches Koffein.

Darum sollten gesundheitsbewusste Teefans nicht zu viel des grünen Lebenselixiers konsumieren. Kinder oder Menschen, die koffeinhaltige Getränke generell schlecht vertragen, sollten lieber ganz die Finger davon lassen. Für alle anderen ist Matcha eine perfekte Alternative zu Espresso oder Frühstückskaffee. Denn Matcha enthält konzentriert alle Inhaltsstoffe, die Grüntee so gesund machen. Darunter zahlreiche sekundäre Pflanzenstoffe

mit antioxidativer Wirkung wie Polyphenole und Catechine, aber auch die Vitamine A, B, C und E. Das verwandelt Matcha in einen echten Detox- und

Anti-Aging-Drink. Schließlich kann man Matcha-Pulver auch äußerlich für eine straffende Gesichtsmassage oder als Zutat für ein selbstgemachtes

Peeling verwenden. Wie bei allen Superfoods gilt auch bei Matcha: Nur regelmäßig und über einen längeren Zeitraum genossen, entfaltet der Tee

seine positive Wirkung. Allerdings muss er dazu nicht unbedingt pur getrunken werden. Mit dem Tee-Puder lässt sich z. B. auch eine Matcha-Latte

zubereiten. Außerdem ist Matcha eine echte Powerzutat für selbstgemachte Smoothies oder Fruchtsäfte.

Qualität hat ihren Preis

Doch Achtung: Seitdem das grüne Energiebündel in Europa einen Boom erlebt, sind zweifelhafte Matcha-Qualitäten im Umlauf. Echter Matcha ist

sehr teuer. 30 Gramm können das Budget locker mit 30 Euro und mehr belasten. Die Billigvariante wird oft aus minderwertigem Rohtee bzw. dem ganzen Blatt hergestellt und mit Metallmühlen zermahlen. Dabei wird das Teepulver, anders als in Steinmühlen, stark erhitzt. Viele der Inhaltsstoffe und ätherischen Öle gehen so während der Herstellung unwiederbringlich verloren. Vom feinen Aroma ganz zu schweigen. Lieber ein bisschen mehr ausgeben und Matcha wie jedes Genussmittel in Maßen genießen. Und noch einen Wermutstropfen gibt es: Wer seinen Matcha mit Milch mischt, blockiert damit die Aufnahme zahlreicher Inhaltsstoffe. Eine Matcha-Latte ist zwar lecker, bringt gesundheitlich aber nicht so viel, wie Matcha pur oder im milchfreien Smoothie. Das gilt auch für Soyamilch und andere vegane Milchalternativen, die Eiweiß enthalten.

Aufbewahrt werden sollte Matcha trocken, kühl und lichtgeschützt – am besten im Kühlschrank. Hochwertiger Matcha-Tee wird meist in kleinen Metalldöschen verkauft. Vorm Aufgießen soll, wie generell bei grünen Teesorten, das aufgekochte Wasser auf ca. 70 Grad abgekühlt werden. Auch das schont die wertvollen Inhaltsstoffe. Übrigens: Statt des Chasen lassen sich zum Aufschlagen auch Milchaufschäumer verwenden – das Ergebnis kommt an handgeschlagenen Matcha allerdings nicht heran.

So Schön grün

Zubehör für die Zubereitung und Bio-Matcha-Tee gibt es bei http://www.imogti.com

Schön sein mit der Hautpflegeserie Kosho mit Matcha-Grüntee. Für die Beauty-Produkte wird feinstes Matcha-Pulver in einem eigens dafür in der Schweiz entwickelten Verfahren zu Bio-Matcha-Extrakt veredelt. Smart Protection Cream 116 €/50 ml. http://www.kosho.com

Schicke Schale Die gibt es zusammen mit Besen und Portionierlöffel hübsch verpackt als Einsteiger-Set bei Kobu. Der Teehandel bietet ein umfangreiches Zubehör- und Tee-Sortiment. 34,95 €. http://www.kobu-teeversand.de

Titelbild: www.kobu-teeversand.de

Matcha: Die grüne Energie Tee ist eines der ältesten Kulturgetränke der Welt. Schon vor 5000 Jahren wurden in China Teesträucher kultiviert.

0 notes

Photo

Nhiều du khách không biết rằng trước khi biểu diễn, Geisha chỉ tự trang điểm, còn một người đàn ông sẽ giúp họ mặc kimono vì trang phục này có nhiều lớp dày và nặng, phần đai có thể dài tới 7,5 m. Những người đàn ông nhận nhiệm vụ này được gọi là otokoshi, họ là một hình tượng đặc biệt trong thế giới geisha và maiko (những cô gái tập sự thành geisha).

Geisha là những người có khả năng biểu diễn nghệ thuật tinh tế, thường đàn hát, nhảy và mua vui tại những bữa tiệc rượu của giới thượng lưu Nhật Bản. Hình ảnh quen thuộc của geisha là những cô gái trang điểm da mặt trắng sứ với lớp phấn dày, môi đỏ chúm chím và tóc búi cao trong trang phục kimono truyền thống. Ảnh: Pinterest.

Nhiếp ảnh gia Mỹ John Paul Foster có dịp tiếp xúc với Kojima-san, một otokoshi, trong thời gian ông tác nghiệp ở Kyoto, Nhật Bản. Kojima-san là một trong 5 otokoshi làm việc tại quận Gion Kobu, phục vụ hơn 90 maiko và geiko (tên gọi của những geisha ở Kyoto). Công việc của họ đều là cha truyền con nối.

Kojima-san cho biết, công việc của anh không chỉ giúp các geisha hay maiko mặc đồ hàng ngày. Trách nhiệm lớn nhất của những otokoshi là đảm bảo mọi phục trang của họ được đưa về nhà an toàn sau mỗi bữa tiệc hoặc buổi biểu diễn.

Kojima-san (phải) đi cùng một geiko. Ảnh: Pinterest.

Kojima-san đặc biệt bận rộn vào dịp nhà hát Gion Kobu Kaburenjo tổ chức điệu Miyako Odori, rất nhiều geisha sẽ tham dự. Anh phải đưa bất kỳ thứ gì các cô gái để quên hay đánh rơi tại nhà hát về.

Ảnh: Công việc thường nhật của otokoshi tại Kyoto

Kojima-san gặp nhiều khó khăn hơn mỗi khi phải làm việc với các geisha có thâm niên trong nghề, vì họ luôn có những yêu cầu đặc biệt. Ví dụ, Kojima-san sẽ phải biết đặt đai áo ở vị trí nào khi mặc kimono cho họ, chỉ cần anh buộc lệch vài centimet họ cũng sẽ biết và nhắc anh điều chỉnh.

Ngày erikae (khi các maiko trở thành geiko) không phải thời khắc nhiều cảm xúc với Kojima-san. Anh cho biết, chỉ mất 5 phút để một otokoshi giúp một geiko hay maiko mặc quần áo nên giữa họ không có nhiều thời gian tương tác. Vào những dịp đặc biệt hơn, các otokoshi cũng chỉ cần 15 phút để chuẩn bị phục trang cho những cô gái.

Điều đáng buồn nhất mà Kojima-san chia sẻ chính là nhiều thay đổi lớn xảy ra tại quận Gion Kobu trong khoảng 20 năm trở lại đây, những quán trà không còn đông khách như trước. Điều này dấy lên nỗi lo cho tương lai của geiko, maiko và cả những người hỗ trợ họ. Kojima-san hy vọng rằng nét văn hóa này sẽ không bị mai một tại Nhật Bản.

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (12): (1587) Twelfth Month, Eleventh Day, After the Morning Meal.

12) Twelfth Month, Eleventh Day¹; following the morning meal, fu-ji [不時]².

◦ Three-mat room³.

◦ (Guests:) Toda minbu [戸田民部]⁴, Ikeda Bicchū [池田備中]⁵.

First⁶:

﹆ One bowl of usucha was served⁷.

◦ Mizusashi Bizen [水指 備前]⁸;

◦ nakatsugi [中次]⁹.

▵ Kobu aburite ・ kuri [コフ アフリテ ・ 栗]¹⁰.

◦ [Then,] using the na-kago [菜籠], a full-set of charcoal was laid [in the ro]¹¹.

◦ Kama unryū [釜 雲龍]¹².

◦ On the tana, the kōgō and habōki¹³.

◦ Toko Tōyo [床 東與]¹⁴ -- [it had been] hanging from the beginning¹⁵.

◦ After [the scroll in the] toko was rolled up¹⁶, in a take-zutsu [竹筒], plum [blossoms]¹⁷.

◦ Chaire Shiri-bukura [茶入 尻フクラ], on [its] tray¹⁸;

◦ temmoku [天目]¹⁹;

◦ mizusashi Bizen [水指 備前] -- [the same] as in the beginning²⁰.

_________________________

¹Jūni-gatsu jūichi-nichi [十二月十一日].

The Gregorian date for this chakai was January 19, 1587.

²Asa-han ato fu-ji [朝飯後 不時].

In other words, after taking the morning meal, it was spontaneously decided to have a chakai.

Both guests were numbered among Hideyoshi's personal guards, and had probably been on guard duty the night before -- after which they would have been served breakfast before being dismissed. It seems that the two decided to stop by Rikyū's residence for chanoyu on their way home.

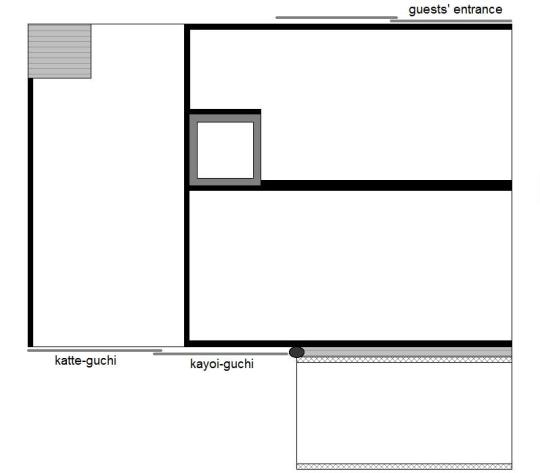

³Sanjō shiki [三疊敷].

This entry is problematic. The “3-mat room” that is occasionally mentioned in his kaiki generally refers to Nambō Sōkei's Shū-un-an (illustrated below), which he seems to have borrowed when receiving certain guests in his own home would have proven inappropriate*.

That said, there is no indication that this gathering was held in Sakai -- and, indeed, it would have been difficult for the guests to “suddenly” visit Rikyū there after taking their morning meal elsewhere, if the chakai were held in Sakai (in addition to the distance between Ōsaka and Sakai, Japanese citizens -- and particularly important officials such as these -- could not freely enter Sakai on the spur of the moment).

While Shibayama Fugen's entry concurs with what is found in the Enkaku-ji copy of the text, Tanaka Senshō states that the room was a nijō shiki [二疊敷] -- which would mean the two-mat room in Rikyū's residence.

In fact, though Tanaka does not mention that his copy deviates from other versions† (as he usually does when any of the then-known texts vary from the others), given that this was a fu-ji no chakai [不時の茶會], the two-mat room in Rikyū's official residence within Hideyoshi's Ōsaka castle complex would be a more logical place for these two important warriors to visit on the spur of the moment.

The kaiki is rather disorganized, which suggests that it may not have been part of Rikyū's manuscript, but added (from other sources) by someone else at a later date.

__________

*A “three-mat room” is mentioned in some of the kaiki written by other people (such as Kamiya Sōtan), but the details are confusing -- for example, though the room is called a three mat room (with 5-shaku toko -- similar to the original Tai-an room), it seems that there was either a daime appended to the room, or else the maru-jō utensil mat was used like a daime (perhaps it had a sode-kabe at the end, like the original Tai-an). Since Tanaka Senshō's manuscript states that it was a 2-mat room, and in the absence of any clear details, it seems best to treat this as a 2-mat room -- since this “3-mat room” is only mentioned this once (all other references clearly refer to the Shū-un-an).

†Tanaka Senshō used a handmade copy of the text as his teihon [底本], which was copied much earlier than the text consulted by Shibayama Fugen.

It is possible that the reading of the Enkaku-ji text is unclear -- the document shows a certain amount of insect damage which might make a two (ni [二]) seem to be a three (san [三]). Unfortunately, circumstances now make it difficult for me to confirm this.

⁴Toda minbu [戸田民部].

This refers to the bushō [武将] Toda Katsutaka [戸田勝隆; ? ~ 1594], who was the Assistant Vice-minister of Public Affairs (minbu-no-sunaisuke [民部少輔], also pronounced minbu-no-shōyu).

Katsutaka had been a personal retainer of Hideyoshi's, serving in his mounted guard, and so was in a position of great trust (since he was permitted to appear armed in Hideyoshi's presence). He participated in many of Hideyoshi's campaigns, and was part of the committee that negotiated the truce that formalized the cessation of hostilities following the First Invasion of the Continent. However, he was taken ill on the return journey, and died before reaching his homeland.

Katsutaka was also one of Rikyū's personal disciples, and was one of the small group of men permitted to receive the gokushin teachings by Hideyoshi.

⁵Ikeda Bitchū [池田備中].

This was the daimyō Ikeda Nagayoshi [池田長吉; 1570 ~1614], who held the junior grade of the Fifth Rank as Governor of the province of Bitchū (Bitchū-no-kami [備中守]). He was also one of Hideyoshi's personal retainers, and had the distinction of having been adopted by Hideyoshi.

Nevertheless, at the battle of Sekigahara (1600), Nagayoshi supported the claims of Tokugawa Ieyasu, and was afterward rewarded with Tottori castle (Tottori-jō [鳥取城]), which remained in his family throughout the Edo period.

In the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki, Ikeda Nagayoshi appeared as a fellow guest together with Toda Katsutaka at a chakai that Rikyū gave for them on the 10th day of the First Month of Tenshō 19 (1591), also in the morning, suggesting that (on both this and the other occasion) they visited Rikyū on their way from Hideyoshi's residence.

⁶Ubu [初].

Though the kanji is the same, ubu [初] does not mean the shoza, as it does in most of the entries; it means “first” or “beginning” -- that is, that the service of usucha happened at the beginning of this fuji-no-chakai.

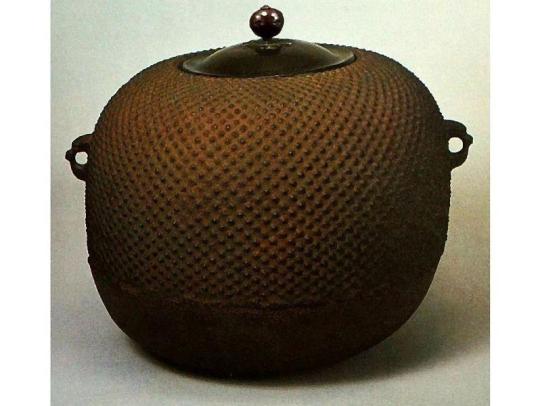

The scroll in the toko had been hung up at dawn, after the room was swept, at which time the fire would have been put into the ro, and a large kama (perhaps the Temmyō ko-arare uba-guchi gama [天命小霰姥口釜], below, that Rikyū used at his previous chakai) placed over it to heat -- despite the fact that nobody had been invited for chanoyu that day.

When the two men arrived, noticing that the kama from dawn was still boiling, Rikyū invited them into the small room for usucha (using some left-over matcha that he happened to have on hand), after which he removed the larger kama, rebuilt the fire (while simultaneously having some fresh matcha ground in the mizuya), and put the small unryū-gama, filled with fresh water, on to boil, so he could serve the guests especially delicious koicha.

Shibayama Fugen suggests that the temae at the beginning of the chakai, at which only one bowl of usucha was served*, was probably a hakobi-temae [運び手前], meaning that Rikyū brought the mizusashi, chawan and nakatsugi, and hishaku, futaoki, and koboshi, out from the katte, served tea, and then took these things away (perhaps without haiken)†.

Tanaka Senshō, furthermore, adds that the kōgō and habōki were displayed on the tana from the start, so that the kane-wari for the “shoza” was:

◦ toko: kakemono, han [半];

◦ room: kama, han [半];

◦ tana: kōgō and habōki, arranged side by side, chō [調].

Han + han + chō equals chō, which is appropriate to the shoza -- even though usucha was served.

__________

*Though modern-day conventions suggest a single large bowl of usucha was passed around for all to share, in Rikyū's day offering each guest an individual bowl of usucha would have been the usual way to do this.

†That said, this kind of temae was usually considered more appropriate to a 4.5-mat room, since in the smaller rooms, the host was supposed to keep his entrances and exits to a minimum. That is why the room had a built-in tana.

Nevertheless, the present chakai seems to provide an exception -- since there would be no way to display both the tea utensils and the kōgō and habōki at the same time while still adhering to the rules of kane-wari -- and good taste.

⁷Usucha ippuku [薄茶一服].

Probably each guest was served one bowl of usucha -- even though, according to the modern custom, zen-cha [前茶]* is usually served as sui-cha [吸い茶]†. Rikyū writes the word ippuku to indicate that the service of usucha was truncated -- rather than allowing the guests to drink as much as they wanted‡.

__________

*Zen-cha [前茶] means usucha served at the beginning of a chakai or chaji.

The reader must be careful not confuse this with Zen-cha [禪茶], which means Zen-tea (or Zen and tea).

†Sui-cha [吸い茶] means a single bowl of tea is shared by all the guests, being passed from hand to hand with each drinking a portion.

‡As is usual when usucha follows koicha -- in the ordinary case where usucha follows koicha, the limiting factor would be only how much matcha remains in the tea container.

⁸Mizusashi Bizen [水指 備前].

This seems to have been the same mizusashi that Rikyū used during the previous chakai.

⁹Nakatsugi [中次].

A nakatsugi* was a storage container, used to keep tea for several days (so it would not spoil, and could still be served as usucha).

This suggests that Rikyū was using tea that had been ground for a previous chakai to serve as usucha first -- while the matcha that he would serve as koicha was being ground in the mizuya.

Though nothing is said about the chawan, Rikyū may have used the same one that he mentions later in the kaiki -- apparently his Seto-temmoku [瀬戸天目], used without a dai.

As for the other things, Rikyū would have used an ori-tame [折撓] of the usual length†, as well as a take-wa [竹輪] and mentsū [面桶].

__________

*While Rikyū clearly states when he used the nakatsugi that was made for him by Tenka-ichi Seiami [天下一盛阿彌] (Hideyoshi's personal lacquer artisan), this nakatsugi would have been an ordinary storage container -- that period's equivalent of Tupperware.

†He probably changed the chashaku afterward for a smaller one, made to match the bon-chaire that he used when serving koicha during the latter part of the chakai.

¹⁰Kobu aburite ・ kuri [コフ アフリテ ・ 栗].

After serving his guests a bowl of usucha (essentially, to wash down their breakfasts -- which they had probably taken in Hideyoshi's residence), Rikyū offered them some light refreshments (to prepare them for the koicha that would be served later).

This consisted of toasted kelp and roasted chestnuts†.

__________

*Kobu [コフ = こぶ] is usually pronounced (and written) kombu [こんぶ = 昆布] today.

†Kuri [栗] is Rikyū's abbreviated way of writing yaki-guri [燒栗].

¹¹Na-kago ni te issumi [菜籠ニテ一炭].

This was Rikyū's na-kago sumi-tori [菜籠炭斗].

Issumi [一炭] means a full set of charcoal. Since the fire had been laid at dawn, while the guests had arrived after the morning meal (which was generally served in the middle of the morning), the charcoal would have mostly burned away by the time that Rikyū finished serving a bowl of usucha to each of the guests immediately after they arrived. Therefore, after taking the kama out to the mizuya*, he would have collected the embers together into the middle of the ro, and then laid a full set of charcoal around them.

After adding the incense to the ro, Rikyū would have returned to the katte and brought out his bamboo jizai (which he suspended from the hook attached to the ceiling), and then brought out the wet small unryū-gama, which he suspended over the ro†.

__________

*It would not be reused, since a large kama would take too long to return to a boil. Also, since the matcha was being ground freshly, pure water that had not been boiling in the kama too long would make for the best-tasting koicha. Thus, Rikyū substituted the small unryū-gama for the other, before the eyes of the guests, during the sumi-temae.

†Given its small size, the kama would begin to boil in around 15 minutes, so that after the sumi-temae, the guests would have gone out to the koshi-kake for the naka-dachi -- and to use the restroom -- and they would have been ready to return about the time that the kama began to boil.

¹²Kama unryū [釜 雲龍].

This was the second small unryū-gama [小雲龍釜], with matsu-gasa kan-tsuki [松笠鐶付] and a cast-iron lid.

It was suspended over the ro on Rikyū's abura-dake jizai [油竹自在], using his bronze kan and tsuru.

¹³Tana ni kōgō ・ habōki [棚ニ 香合 ・ 羽帚].

The kōgō would have been Rikyū's ruri-suzume [瑠璃雀], which was the one that he ordinarily used with the ro.

And the habōki would have been a go-sun-hane, as appropriate to the small room, most likely made of shima-fukurō [嶋梟] feathers, as shown above.

¹⁴Toko Tōyo [床 東與].

This refers to a bokuseki written by the Yuan dynasty monk Dōnglíng Yǒng-yú [東陵永璵; 1285 ~ 1365]* (whose name is pronounced Tōryō Eiyo in Japanese).

He is said to have been related to the great Chán master Wúxué Zǔyuán [無學祖元; 1226年 ~ 1286] (Mugaku Sogen in Japanese). Both Wúxué and Dōnglíng emigrated to Japan in order to spread the orthodox Chán teachings.

Dōnglíng Yǒng-yú was a follower of the Sōtō sect [曹洞宗] of Chán; and, as mentioned above, he came to Japan in Shōhei 6 [正平六年] (1351). Although he was a monk of the Sōtō Shū, he served as the abbot (jūji [住持]) of a number of important Japanese temples that had no affiliation with that sect, among which were the Tenryū-ji [天龍寺] and Nanzen-ji [南禪寺] in Kyōto, and the Kenchō-ji [建長寺] and Enkaku-ji [圓覺寺] in Kamakura.

The kakemono in question was more likely the hōgo [法語] that is shown above.

___________

*When writing this abbreviated version of his name (it uses the first and last of the four kanji), Rikyū has mistaken the second kanji -- writing yo [與] (a kanji found in his own childhood name of Yoshirō [與四良]), rather than yo [璵].

According to this form, the name should have been written Tōyo [東璵].

¹⁵Hajime yori kakaru [初よりカヽル].

In other words, the scroll, while mentioned here, was actually hanging in the tokonoma when the guests entered the room.

This kaiki was set down in a very haphazard manner.

¹⁶Toko makite [床巻テ].

This is one of Rikyū's abbreviations, and means that the scroll was rolled up, and removed from the toko. (It does not mean, as Tanaka Sensho implies, that the rolled-up scroll was displayed on the floor of the toko*.)

__________

*Sometimes a scroll was arranged in this way, to display its gedai [外題] -- a sort of title (it usually included the name of the artist responsible for the scroll) that was written on a small slip of paper, which was glued to the back side of the scroll near the roller.

However, scrolls were displayed in this way first, and only after the guests had inspected the gedai was the scroll hung up so they could look at the honshi.

¹⁷Take-zutsu ni ume [竹筒ニ梅].

As discussed in the previous post, prior to the summer of 1590, the word take-zutsu [竹筒] referred to what is otherwise known as an oki-zutsu [置き筒], a length of bamboo that was stood on an usu-ita on the floor of the toko, for use as a hanaire.

Given the time of year, the plum blossoms were probably of the early-flowering pink variety.

This entry begins the list of the things displayed at the beginning of the goza. In terms of kane-wari:

◦ toko: chabana, han [半]*;

◦ room: kama, mizusashi (with the bon-chaire and temmoku placed, side by side, in front of it), chō [調];

◦ tana: nothing, making it chō [調].

Han + chō + chō equals han, which is appropriate to the goza.

__________

*As mentioned above, Tanaka Senshō, in his commentary on the kane-wari, inexplicably argues that the kakemono, after it was rolled up, was left in the toko (this interpretation of toko makite [床巻テ] actually goes against the way he has understood these words on previous occasions), with the chabana added to it (though where it may have been placed -- or perhaps he imagines that it was hung up on the hook? -- he does not venture to say). This throws the entire kane-wari scheme off; so that he then has to argue that the bon-chaire must be counted separately from the mizusashi in order for the total to be han [半].

This is what happens when one is playing with disembodied words, rather than approaching the matter with an understanding of what the utensils actually are.

¹⁸Chaire Shiri-bukura bon ni [茶入 尻フクラ 盆ニ].

The chaire that he named Shiri-bukura [尻膨]* was Rikyū's treasured karamono ko-tsubo chaire [唐物小壺茶入].

This chaire holds sufficient matcha to serve two, or possibly three, guests. It would have been filled with the just-ground matcha.

The tray is exactly 2-sun larger than the chaire on all fours sides. That means that the bon-chaire can be placed in front of the mizusashi and the chaire will be separated from it by 2-sun, just like a chaire without a tray. Consequently, with respect to kane-wari, the mizusashi and the things in front of it are counted together as a single unit (just as when an ordinary chaire is displayed in front of the mizusashi)†.

Furthermore, for the same reason, the temmoku-chawan (without a dai) could be displayed on the mat next to the bon-chaire while still adhering faithfully to the teachings of kane-wari‡.

And though not mentioned, Rikyū would have used a (different) ori-tame (chashaku), one that he had made to match this bon-chaire.

__________

*The name comes from its shape. The widest part of its circumference is at the hips, which is what the name means.

†This is true for all of the chaire that Rikyū paired with trays (though it is usually not true for trays paired with chaire by most other people of his generation, or before, or after).

‡When a chawan is placed next to the bon-chaire, the distance between the chawan and the chaire is also 2-sun, which is the same as when a tray is not present.

Unless these things are understood, it will be impossible to understand Rikyū’s usages -- or the way his arrangements conform to the teachings of kane-wari.

¹⁹Temmoku [天目].

While not described further, this was probably Rikyū's Seto-temmoku [瀬戸天目] shown below.

Since nothing is said (and, indeed, the fact that this was an impromptu chakai argues against it), the temmoku was probably displayed on the utensil mat (next to the bon-chaire) without its dai, with the chakin, chasen, and chashaku arranged in it as if it were an ordinary chawan.

Possibly the temmoku was also used at the beginning of the chakai, to serve usucha (since Rikyū disliked using any more utensils than absolutely necessary).

²⁰Mizusashi Bizen hatsu no [水指 備前 初ノ].

This means that the mizusashi was the same one that had been used when serving usucha at the beginning of the chakai. This, too, suggests that the chawan may also have been the same.

As for the futaoki and koboshi, these would have been a take-wa [竹輪] and a mentsū [面桶] -- the mentsū probably being a new one, rather than the one used during the service of usucha earlier.

0 notes