#look upon my niche shit art and suffer.

Text

some sort of implicit blessing

#i hate this but i had fun#doodle#crappy art#its archivin time#tma spoilers#oh king i'm sorry you were right#it is important to have one very specific weird guy on the internet for a piece of media. necessary for the ecosystem.#i am that one very specific weird guy in this case#look upon my niche shit art and suffer.

157 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Survival Mode.

In ten recent coming-of-age films, Ella Kemp finds the genre thriving—and looking very different than the 1980s might have predicted. Film directors and Letterboxd members weigh in on the specific satisfactions of the genre, especially in a pandemic.

There have been jokes, some more serious than others, about the art that will come out of this time. How many novels about a fast-spreading disease are you betting on? Will Covid-19 be better suited to documentary or fiction? But the art I’m most looking forward to, and revisiting now, is the art made about teenagers going through it.

Physical school attendance, so central to the John Hughes movies of the 1980s, is up in the air for so many. Sports practice, theater clubs, mall hang-outs; the familiar neighborhood beats of a teenager’s life are more confined than ever. All of us have had to tweak our reality to make the best of invasive changes forced upon us during the pandemic. In a sense, it feels like we are all coming of age.

Teenagehood, though, is a particularly tricky time of transition, and we don’t yet know the half of how the pandemic is going to impact today’s young adults—and, by association, tomorrow’s coming-of-age films. But in the last two years alone there have been enough brave new entries in the genre, about young people so enlivening, that there’s both plenty for young film lovers to lose themselves in, and plenty for us slightly older folks to watch and learn from.

So I sought out ten recent coming-of-age films (and several of the directors responsible) to see what these stories teach us about teenagers, and how we might empathize with them. The list—Jezebel, Beats, Zombi Child, Blinded by the Light, Selah and the Spades, The Half of It, Dating Amber, Babyteeth, House of Hummingbird and We Are Little Zombies—is by no means exhaustive. But it allows us to look at several things.

Firstly, that the genre is thriving, considering these titles barely scratch the surface. Secondly, these ten films look a whole lot different than their 1980s counterparts. Six are directed by women. Four tell queer stories or, at least, feature queer characters in a prominent subplot. Seven tell stories about Black people, Asian people, Pakistani people. Only three are from the US.

And: they’re really good. They understand teenagers as angry, energetic, passionate, confused, desperate and deeply intelligent beings, echoing the nuances that we know to be true in real life, but that can often get watered down on the screen.

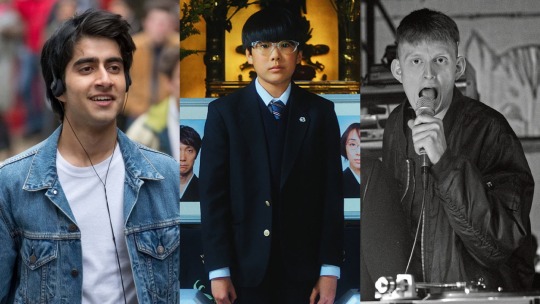

Blinded by the Light (co-written and directed by Gurinder Chadha)

We Are Little Zombies (written and directed by Makoto Nagahisa)

Beats (co-written and directed by Brian Welsh)

The protagonists in these first three films use music to feel their way through panic, brought on by both internal and external circumstances. Screaming another’s lyrics, furiously composing their own anthems, dancing along and sweating out their fear to the beat, the ongoing beat, and nothing more. It’s salvation, it’s release—when you’re left with your own thoughts, the only way to fight through them is to drown them out.

Music acts as a source of enlightenment in Blinded by the Light, directed by Gurinder Chadha (who made 2002’s coming-of-age sports banger Bend it Like Beckham). In Thatcher’s Britain, Pakistani-English Muslim high schooler Javed discovers the music of Bruce Springsteen, and his world bursts wide open. The wisdom and fire of the Boss helps Javed to make sense of his own frustrations; that the film is based on a real journalist’s autobiography makes it all the more potent.

Meanwhile, in Beats, a real-life law enacted in Scotland in the 1990s temporarily banned raves: specifically, the gathering of people around music “wholly or predominantly characterized by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats”. As the UK struggles to contain a youthful, exuberant new counter-culture, the central characters face what it means to enter adulthood. The answer to both: a forbidden rave.

“I have to say, there’s probably no such thing as teenagers without complicated emotions,” We Are Little Zombies writer-director Makoto Nagahisa tells me. The Japanese filmmaker—who loves the genre, known as ‘Seishun eiga’ in Japan—wrestles with the frustration and hopelessness of the world by giving his film’s four orphaned teens the tools, and the permission, to find solace in something other than their everyday life. Following the deaths of their parents, the quartet create their own catchy, cathartic, truth-bomb music; it’s an instant hit with kids across Japan, but the adults miss the point, of course—that the cacophony of superstardom is filling the silence of their mourning.

Nagahisa-san’s film is named after a fictional 8-bit Nintendo Game Boy game that the main character is addicted to. “I used to get through my day relatively painlessly by pretending I was a video game character whenever bad shit happened to me,” he explains. Teenagers “are constantly feeling crushed by reality right now… I want them to know that this is a valid way to escape reality. That reality is just a ‘game’. I want them to know they don’t need to face tragedies, they can just survive. That’s the most important thing!” Who else needed to hear that right now?

Jezebel (written and directed by Numa Perrier)

Zombi Child (written and directed by Bertrand Bonello)

Selah and the Spades (written and directed by Tayarisha Poe)

House of Hummingbird (written and directed by Kim Bo-ra)

Our next four films turn to technology, mythology, hierarchy and education to animate their protagonists’ lives with a greater purpose. In Jezebel, nineteen-year-old Tiffany finds her way through mourning with a new job, earning money as a cam girl and subsequently developing a bond with one of her clients. There’s a magnetic aura, one that harnesses grief and turns it into something more corrosive as this teen puts all her energy into it. Similarly there’s mysticism in the air in Zombi Child, in which Haitian voodoo gives a bored, heartbroken teenage girl a new purpose as she searches for a way to connect with the one she lost—and with herself.

Selah and the Spades and House of Hummingbird understand the third-party saviour as more of a structure, that of a school or an inspiring teacher. Selah finds herself by doing business selling recreational drugs to her classmates in a faction-led boarding school. Nothing mends a sense of aimlessness like power. This same framework lets Hummingbird’s Eun-hee, a schoolgirl in mid-90s South Korea whose abusive family invest their academic focus in her useless brother, search for love and find connection in her school books—and from the person who’s asking her to read them.

The films on this list are not perfect; some might be criticized for specifically following a formula, the tropes of the coming-of-age film, a little too well. Jezebel lets its protagonist rise and fall with familiarity, while Selah suffers the consequences of her extreme actions, and even Eun-hee reckons with a few recognizable pitfalls. But still, the fact that these films exist is “innately radical”, says Irish writer-director David Freyne, whose queer Irish comedy Dating Amber is covered below. The filmmaker describes the coming-of-age genre as mainstream, but in the best possible sense: “It’s a broadly appealing film,” he says.

This is why, to see these stories reframed with minority voices, with queer voices, is so quietly revolutionary. “The more you see them, the more broadly we see them being enjoyed—the more producers and financiers will realize these stories don’t have to be niche just because they happen to frame a minority voice. Everyone can enjoy it.”

Film journalist and Letterboxd member Iana Murray, a coming-of-age genre fan, echoes Freyne’s thoughts. “Representation is absolutely not the be-all end-all, but I’d love to see more coming-of-age films that reflect my experiences growing up as a woman of color,” she says, before introducing what I’d like to call the Rashomon Effect. “I see it as like one of those films that tell the same events from different perspectives, something like Rashomon or Right Now, Wrong Then,” she explains. “A story becomes even more vibrant when told through a different set of eyes, and that’s what happens when you allow women, people of color, and LGBT people to create coming-of-age narratives.”

Dating Amber (written and directed by David Freyne)

The Half of It (written and directed by Alice Wu)

Babyteeth (directed by Shannon Murphy, written by Rita Kalnejais)

Which brings us on nicely to our last three: wildly different titles, each with young protagonists at war with themselves, trying to make sense of their bodies and minds as best they can. In this context, companionship is everything. Finding a platonic soulmate in Dating Amber, a sexual awakening in The Half of It, a first love to make a short life worth living in Babyteeth. Each film is directed with a verve and passion that you know must be personal.

The story of a frustrated boy in the closet in Dating Amber aches with care from Freyne behind the camera, while Alice Wu directs Ellie Chu, the main character in The Half Of It, with patience and the kind of encouragement that quiet girls who live a life between two cultures are rarely given. And with Babyteeth, Shannon Murphy returns Australian cinema firmly to the center of the movie map, with a quintessentially Australian optimism and sense of humor, which Ben Mendelsohn called “delightfully bent”.

These perspectives are specific to each teen, but the intensity transcends genres and borders. It manifests musically, verbally, visually, aesthetically. These teens connect with their favorite music and means of entertainment, but also simply to their favorite clothes and accessories—blue bikinis and green wigs, red neck-scarves and floaty white dresses. These details give the characters ways to reinvent themselves while standing still, which certainly feels apt for a life lived, for now, at home.

‘Pretty in Pink’ (1986), written by John Hughes and directed by Howard Deutch.

Many argue that the coming-of-age genre peaked with John Hughes, who defined the framework in iconic 1980s films that have his stamp all over them, whether he wrote (Pretty in Pink, Some Kind of Wonderful) or also directed them (The Breakfast Club, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Sixteen Candles). Hughes’ world view was of a specifically suburban, white, American corner of the world, which he filled with misfits and ultra-hip soundtracks. “John Hughes was to the genre what The Beatles are to rock and roll,” confirms Letterboxd member Brad, maintainer of the essential coming-of-age movie list Teenage Wasteland.

After Hughes, the genre tumbled, Dazed and Confused, into the 1990s—notable voices include John Singleton with his seminal Boyz n the Hood, and Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho and Good Will Hunting. This was also the decade of Clueless, which informed the bright, female-forward fare of the 2000s, like Mean Girls, The Princess Diaries and the aforementioned Bend it Like Beckham. The last decade has seen new American storytellers step into Hughes’ shoes, including Greta Gerwig (Lady Bird and Little Women), Olivia Wilde and the writers of Booksmart, and the autobiographical voices of Jonah Hill (mid90s) and Shia LaBeouf (Honey Boy, directed by Alma Har’el).

It’s interesting to note—whether it’s the 1860s or the 1980s—that many coming-of-agers from the past decade take place in an earlier period setting. Social media has demanded the upheaval of entire lives, but it seems some filmmakers aren’t yet ready to grapple with its place on screen.

The audience, on the other hand, is far more adaptable. The way we’re watching coming-of-age films has shifted, and it’s more appropriate for the genre than we could have imagined. On the last day of shooting Dating Amber, Freyne recalls one of the young actors asking, “So, is this going to be on Netflix or something?” This is when cinemas were still open.

“That’s often how younger people are devouring content now,” Freyne reasons. His film, in the end, was snapped up by Amazon (a US release date is yet to be announced). “It’s creating a communal experience with the intersection of social media: live streams, fan art, daily messages… It’s made us feel incredibly connected, moreso than I think we would have got with a cinematic release.”

Streaming platforms also cater to one key habit of a younger film lover: the rewatch. The iconic teen films of the 80s embedded their reputations thanks to the eternal allure of the Friday night video store ritual, and constant television replays. These days, it’s only with a film finding a home on Netflix, on Amazon or on Hulu, that a younger person (or, in times of global crisis, any person) can both financially and logistically afford to devote themselves to watching, again and again, these people onscreen that they’ve immediately and irrevocably found a connection with.

It’s always felt hard to be satisfied with just one viewing of a perfect coming-of-age film—observe how many times Iana Murray has logged Call Me By Your Name. What is it about the slippery, universal allure of the genre? It’s possibly as simple as the feeling of being seen in the fog of intergenerational confusion. Says Nagahisa-san: “Grown-ups think of teenagers like zombies. Teenagers think of grown-ups like zombies. We’re never able to understand what others are feeling inside.”

“The reaction is always emotive rather than intellectual,” adds Freyne. “There’s something quite visceral and instinctive about coming-of-age films; it’s an emotional experience rather than an analytical one.” That emotional experience is tied up in the fact that we often experience coming-of-age movies just as we ourselves are coming of age, establishing an unbreakable connection between a film and a specific period in our lives. MovieMaestro Brad explains it best: “There is a bit of nostalgia in a lot of these films that take me back to my younger days, when life was simple.”

But that’s not to say only those coming of age can appreciate a coming-of-age film. On her favorite coming-of-age film, Mike Mills’ 20th Century Women, Murray explains, “It doesn’t see coming-of-age as exclusive to teenagers, because that process of growth is really about transition and change.” (In a similar vein, Kris Rey’s new comedy I Used to Go Here, in select theaters and on demand August 7, meets Kate Conklin, played by Gillian Jacobs, in a sort of quarter-life-crisis, needing to grow down a bit in order to grow up.)

Natalia Dyer in ‘Yes, God, Yes’ (2019), directed by Karen Maine.

There is endless praise, conflict and wonder to be found in the ten films mentioned above—and all the ones we haven’t even gone near (Karen Maine’s orgasmic religious comedy Yes, God, Yes, now available on demand in the US, deserves an honorary mention, as does Get Duked!, Ninian Doff’s upcoming stoner romp in the Scottish Highlands). The thing about this genre is it’s raw, it’s alive, and it’s always in transition. Just when you might think it’s gone out of fashion, it emerges in a new and fascinating form. And yet, there are still so many filmmakers who haven’t tackled the genre. I asked my interviewees who they’d like to see take on a story of teens in transition.

“I’d love to see Tarantino’s take on a coming-of-age tale,” says master of the genre himself, MovieMaestro/Brad. Murray gives her vote to Lulu Wang, saying, “I love the specificity she brought to The Farewell, I think it would transfer well to a genre that needs to escape clichés.” Freyne, meanwhile, wants to see if Ari Aster might have another story about young people in him. Maybe something a bit less lethal next time.

Ultimately, “you write from empathy, not from experience,” says Freyne. I think the same goes for watching, too. It won’t be tomorrow, and it might not be this year, but eventually, the world will emerge from Covid-19. What will we have learned from the films that we watched while we were waiting? From the sadness, the angst, the determination, the rage and the passion?

Nagahisa-san already knows, and his advice is everything we need right now: “You don’t need others’ approval of who you are, as long as you understand and approve of yourself. Do whatever pops up in your mind. Live your life without fear or despair. Just survive.”

Related content

See where most of the recent releases mentioned here are virtually screening, in our Art House Online list.

Shannon Murphy talks to us about Babyteeth, and shares a list of her favorite Australian films.

Makoto Nagahisa’s 25 favorite teen movies

David Freyne’s 25 favorite LGBTQIA+ films

Growing Pains: The Ultimate Coming of Age Movie Challenge

(Happy) Queer Coming of Age Movies

Coming of age—but make it diverse

#coming of age#coming of age film#john hughes#pretty in pink#the breakfast club#ella kemp#iana murray#david freyne#dating amber#makoto naga#we are little zombies#makoto nagahisa#teenage wasteland#teen films#the half of it#alice wu#ellie chu#blinded by the light#gurinder chadha#bend it like beckham#clueless#mean girls#greta gerwig#lady bird#booksmart#little women#olivia wilde#letterboxd

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s becoming harder and harder for me to find solace in places. the guilt inside me is becoming heavy. i know that if i want something, i need to make it happen, but i am so exhausted of having to do everything myself. and the things i do get help with i feel grateful, of course, but then so guilty that i’m needing to be helped that it’s incapacitating. i’m just so late in the game to everything. i’m so outside of life and what other people are doing. i’ve always felt that way, though. i’m never gonna snap into place like they want me to.

i need to pick a career and stuff. i just have to like shot in the dark pick something at this point because there isn’t going to be some divine calling, my pittance from art commissions is not gonna be enough to sustain me (and i dont think i can get to a point where it will), im just so bogged down knowing that everybody is fuckin poor.

part of me wishes i could wake up and just ‘be normal’. that i could throw away all the weird stupid shit in my life. the trashy little kid bracelets, the clown clothes, the nerdy interests, the ugly monsters (what on earth is an ‘orc’?), the hundreds of heavy and just plain weird records that are sooo boring and irritating and repetitive and loud and obnoxious. all the shit i’ve internalized about stuff i am beyond passionate about, the only fuel that keeps me alive and gives me a reason to wake up in the morning. i read once about brain trauma, that someone suffered an injury and when they woke up, all of their interests changed completely. they were a classically-trained musician, iirc, and ended up just selling all of their instruments and getting rid of all their books etc because it had absolutely no value to them anymore. they were completely changed. i dont remember what their new interests became, but... the thought of that has haunted me for over a decade. maybe someone will hit me in the head just right until i wake up and be a normal person who cares about normal, accessible things instead of all this fringe and abrasive fantasy bullshit. what if i woke up one day and became a devout christian? i roll over and my room is foreign to me, along with everything in it, and then i just throw it all away? i start over, stripped clean. tabula rasa. i get good interests instead. relatable adult things, like gourmet food and backpacking. i titter with the girls at the office and wear pencil skirts and focus on landing me a tall dark and handsome.

the thought of becoming that thing is heartwrenching. painful. but it’s all obvious, of course, why i would ever have that masochistic fantasy of completely disowning my worthless oblong self. a me that isn’t ‘ruined’.

i went through my kandi stash the other day trying to find all my kandi with bells on it (I could have sworn i had more). and going through a lot of it was a flood of memories. high school, college, raver days. when i was in high school, all by my lonesome, the only candy kid or rave-associated ANYTHING in my 4000+ fellow students, i had to wear a lot of my own kandi. and i did so as a beacon, a lighthouse, hoping that i could be a beaming signal to any other candy kids who might be in hiding. and i got so dizzy and self-consuming with my repressed interest that i became a zealot about it, being extremely rude and elitist about my interests because i felt a need to protect them. i felt the pressure of them looking to be watered down or erased. i was the same with warcraft.

ten years later i’m not as rude about it, but i feel exactly the same way. in high school i had to wear my own kandi, would have it ripped off of my arms in big fistfuls by those who ostracized me, and had to be tongue-in-cheek and submissive about my passion, my very real and non-ironic DEVOTION to this. thank god on tumblr i can write 4000 word dissertations about garrosh hellscream and some of you crazy fucks actually bother to read it, but sometimes i still feel like that kind of pariah for having a very niche and very specific fixation.

even people who played warcraft when i was in high school told me i took it too seriously because i roleplayed; and even roleplayers in the game told me i took it too seriously because i didnt want to sit around for 6 hours pretending to drink alcohol and trying to get laid, except as an elf. the fact that i really wanted to discuss the lore and delve into the story and the universe of azeroth, of how it would feel to be in that place, to live that life, ostracized me even from the people who claim to feel the same way. but roleplay was never about focusing on how our veins dont surge anymore as undead, how your digestive organs need to be removed post-undeath so they dont explode and rupture and hang out of your bowels like the abominations in the Undercity, how the undead are technically still the same citizens of Loraderon but are being ousted by their living counterparts in neighboring kingdoms. it was just “haha im a funny dead pirate man and i’m going to womanize 12 blood elf women at once behind all of their backs.”

in trying to become a gabber dj too, i felt like i had to take it upon myself because nobody else plays the music that i like. but alll of these things... it feels like i’m just building a house by myself. i feel like nobody truly, at the core, appreciates the intersection of interests that i have, or can only smile and nod at my fervor but not really understand it. and it’s nobody’s fault, nobody is obligated to feel what i feel.

i’m glad people enjoy the garrosh posts and art that i make. and i’m glad that my friends make kandi with me now and encourage me to play gabber. i’m happy when i get some really good RP, even if i have to be the one to walk up every time. i’m glad that people want me to “do the thing”. i just feel like... there is no payoff once it’s done. everyone gets glad that it’s finished, and they enjoy it then, but then it dissolves. nobody is invested in it but me.

i know the solution is to be more accessible, but i can’t seem to imagine anything other than swinging the pendulum in the opposite direction. like, all or nothing. either you take all of my german expressionism with the warcraft meta and the rave shit, or you get nothing. i dont know how to dilute myself and that’s part of what was killing me at my job. i felt like a novelty. a doll. but it wasn’t their fault.. they couldnt relate to what i was talking about and passionate about, and it’s not their fault. they liked me because i was well-spoken and funny and a diligent worker, which are all nice and accessible things, but when nobody can cathect with me, really empathize with me, i feel like a jester. a consumable.

my college roommates would tell me that they loved me because i was so funny. and that’s it. i existed as entertainment, but anything human about me—my passions, my interests, my insights, my memories—meant nothing. even my family will ask me a question and then cut me off in the middle of my sentence, expressing more of just their disbelief or confusion about something than actually seeking information. it’s why i stopped answering customers when they’d ask “how did you dye your hair?” and, like an idiot, i attempted to explain the process to them, thinking they actually wanted to know. but a few words in and their eyes glazed over, probably because they weren’t expecting a “real answer”. i began to accept that any questions directed toward me were closer to passive acknowledgements of me just standing there and existing in their field of vision than any sort of actual desired input from me. it’s like when people ask “how are you?” and you are obligated to say “fine” because it is the rote response. if you actually start talking about how you are doing, you are violating the socially agreed upon script of pleasantries.

i cant do small talk. i cant do scripts. i dont get it. it doesnt make sense to me. and i think retail killed me because of that. i wasn’t a person. i wasn’t even an NPC. i was just a doll. an actor. a pull-string action figure with 5 fun phrases. i was so wacky and weird with my green hair and my silly bracelets and funny observations. ho ho what fun it is to work here with our personal jester to tell us funny stories about her cuh-razy antics she gets up to!

like how nate said “the craziest thing of someone’s year will be seeing someone play the legend of zelda theme on an accordion at a convention and for us that’s just like a walk down the street”.

my feet straddle two divergent worlds and i cant pick just one but im about to fall in the crevice.

man i fuckin love ratatouille man. i fuckin love that film. i cant choose between two halves of myself. even when the halves want the other half dead.

i need a liaison. where’s MY linguini????

9 notes

·

View notes