#michel lepeletier

Note

I understand the story of marat and his assassination event

But who is lepeletier?

Because I saw a drawing for him by louis David and I learned about his death which happen to be the same as Marat so yeah .. I wanna know about him.

According to the biography Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), its subject of study was born on 29 May 1760, in his family home on rue Culture-Sainte-Catherine, a building which today is the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris. His family belonged to the distinguished part of the robe nobility. At the death of his father in 1769, Lepeletier was both Count of Saint-Fargeau, Marquis of Montjeu, Baron of Peneuze, Grand Bailiff of Gien as well as the owner of 400,000 livres de rente. For five years he worked as avocat du roi at Châtelet, before becoming councilor in Parliament in 1783, general counsel in 1784 and finally taking over the prestigious position of président à mortier at the Parlement of Paris from his father in 1785. On May 16 1789, Lepeletier was elected to represent the nobility at the Estates General. On June 25 the same year he was one of the 47 nobles to join the newly declared National Assembly, two days before the king called on the rest of the first two estates to do so as well. A month later, during the night of August 4 1789, he was in the forefront of those who proposed the suppression of feudalism, even if, for his part, this meant losing 80 000 livres de rente. Four days later he wrote a letter to the priest of Saint-Fargeau, renouncing his rights to both mills, furnaces, dovecote, exclusive hunting and fishing, insence and holy water, butchery and haulage (the last four things the Assembly hadn’t ruled on yet). When the Assembly on June 19 1790 abolished titles, orders, and other privileges of the hereditary nobility, Lepeletier made the motion that all citizens could only bear their real family name — ”The tree of aristocracy still has a branch that you forgot to cut..., I want to talk about these usurper names, this right that the nobles have arrogated to themselves exclusively to call themselves by the name of the place where they were lords. I propose that every individual must bear his last name and consequently I sign my motion: Michel Lepeletier” — and the same year he also, in the name of the Criminal Jurisprudence Committee, presented a report on the supression of the penal code and argued for the abolition of the death penalty. After the closing of the National Assembly in 1791, Lepeletier settled in Auxerre to take on the functions of president of the directory of Yonne, a position to which he had been nominated the previous year. He did however soon thereafter return to Paris, as he, following the overthrow of the monarchy, was one of few former nobles elected to the National Convention, where he was also one of even fewer former nobles to sit together with the Mountain. In December 1792 he started working on a public education plan. On January 20 1793, he voted for death without a reprieve and against an appeal to the people during the trial of Louis XVI (Opinion de L.M. Lepeletier, sur le jugement de Louis XVI, ci-devant roi des François: imprimée par ordre de la Convention nationale). After the session was over, Lepeletier went over to Palais-Égalité (former Palais-Royal) where he dined everyday. The next day, his friend and fellow deputy Nicolas Maure could report the following to the Convention:

Citizens, it is with the deepest affection and resentment of my heart that I announce to you the assassination of a representative of the people, of my dear colleague and friend Lepelletier, deputy of Yonne; committed by an infamous royalist, yesterday, at five o'clock, at the restaurateur Fevrier, in the Jardin de l'Égalité. This good citizen was accustomed to dining there (and often, after our work, we enjoyed a gentle and friendly conversation there) by a very unfortunate fate, I did not find myself there; for perhaps I could have saved his life, or shared his fate. Barely had he started his dinner when six individuals, coming out of a neighboring room, presented themselves to him. One of them, said to be Pâris, a former bodyguard, said to the others: There's that rascal Lepeletier. He answered him, with his usual gentleness: I am Lepeletier, but I am not a rascal. Paris replied: Scoundrel, did you not vote for the death of the king? Lepelletier replied: That is true, because my confidence commanded me to do so.Instantly, the assassin pulled a saber, called a lighter, from under his coat and plunged it furiously into his left side, his lower abdomen; it created a wound four inches deep and four fingers wide. The assassin escaped with the help of his accomplices. Lepeletier still had the gentleness to forgive him, to pray that no further action would be taken; his strength allowed him to make his declaration to the public officer, and to sign it. He was placed in the hands of the surgeons who took him to his brother, at Place Vendôme. I went there immediately, led by my tender friendship, and my reverence for the virtues which he practiced without ostentation: I found him on his death bed, unconscious. When he showed me his wound, he uttered only these two words: I'm cold. He died this morning, at half past one, saying that he was happy to shed his blood for the homeland; that he hoped that the sacrifice of his life would consolidate Liberty; that he died satisfied with having fulfilled his oaths.

This was the first time a Convention deputy had gotten murdered, and it naturally caused strong reactions. Already the same session when Maure had announced Lepeletier’s death, the Convention ordered the following:

There are grounds for indictment against Pâris, former king's guard, accused of the assassination of the person of Michel Lepelletier, one of the representatives of the French people, committed yesterday.

[The Convention] instructs the Provisional Executive Council to prosecute and punish the culprit and his accomplices by the most prompt measures, and to without delay hand over to its committee of decrees the copies of the minutes from the justice of the peace and the other acts containing information relating to this attack.

The Decrees and Legislation Committees will present, in tomorrow's session, the drafting of the indictment.

An address will be written to the French people, which will be sent to the 84 departments and the armies, by extraordinary couriers, to inform them of the crime against the Nation which has just been committed against the person of Michel Lepelletier, of the measures that the National Convention has taken for the punishment for this attack, to invite the citizens to peace and tranquility, and the constituted authorities to the most exact surveillance.

The entire National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepelletier, assassinated for having voted for the death of the tyrant.

The honors of the French Pantheon are awarded to Michel Lepelletier, and his body will be placed there.

The president is responsible for writing, on behalf of the National Convention, to the department of Yonne, and to the family of Lepelletier.

The next day, January 22, further instructions were given regarding Lepeletier’s funeral:

On Thursday January 24, Year 2 of the Republic, at eight o'clock in the morning, will be celebrated, at the expense of the Nation, the funeral of Michel Lepeletier, deputy of the department of Yonne to the National Convention.

The National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepeletier in its entirety. The executive council, the administrative and judicial bodies will attend it as well.

The executive council and the department of Paris will consult with the Committee of Public Instruction regarding the details of the funeral ceremony.

The last words spoken by Michel Lepeletier will be engraved on his tomb, they are as follows: “I am happy to shed my blood for the homeland; I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality; and to make their enemies recognized.”

In number 27 (January 27 1793) of Gazette Nationale ou Le Moniteur Universel, the following long description was given over Lepeletier’s funeral, held three days earlier:

The funeral of Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau was celebrated on Thursday 24 with all the splendor that the severity of the weather and the season allowed, but with such a crowd that it could have been the most beautiful day of the year. At ten o'clock in the morning his deathbed was placed on the pedestal where the equestrian statue of Louis XVI previously stood, on Place Vendôme, today Place des Piques. One went up to the pedestal by two staircases, on the banisters of which were antique candelabras. The body was lying on the bed with the bloody sheets and the sword with which he had been struck. He was naked to the waist, and his large and deep wound could be seen exposed. These were the mournful and most endearing part of this great spectacle. All that was missing was the author of the crime, chained, and beginning his torture by witnessing the sight of the triumph of Saint-Fargeau.

As soon as the National Convention and all the bodies that were to form courage were assembled in the square, mournful music was played. It was, like almost all those which has embellished our revolutionary festivals, the composition of citizen Gossec. The Convention was ranged around the pedestal. The citizen in charge of the ceremonies presented the President of the Convention with a wreath of oak and flowers; then the president, preceded by the ushers of the Convention and the national music, went around the monument, and went up to the pedestal to place the civic crown on Lepeletier's head: during this time, a federate gave a speech; the president dismounted, the procession set out in the following order: A detachment of cavalry preceded by trumpets with fourdincs. Sappers. Cannoneers without cannons. Detachment of veiled drummers. Declaration of the rights of man carried by citizens. Volunteers of the six legions, and 24 flags. Drum detachment. A banner on which was written the decree of the Convention which ordered the transport of Lepeletier's body to the Pantheon. Students of the homeland. Police commissioners. The conciliation office. Justices of the peace. Section presidents and commissioners. The commercial court. The provisional criminal court. The department’s fix courts. The electorate. The provisional criminal court. The department's criminal courts fix. The municipality of Paris. The districts of Saint-Denis and the village of L’Égalité. The Department. Drum detachment. The seal of the 84, worn by Federates. The provisional executive council. National Convention Guard Detachment. The court of cassation. Figure of Liberty carried by citizens. The bloody clothes worn at the end of a national pike, deputies marching in two columns. In the middle of the deputies was a banner where Lepeletier's last words were written: "I am happy to shed my blood for my homeland, I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality, and to make their enemies known.”

The body carried by citizens, as it was exhibited on the Place des Piques. Around the body, gunners, sabers in hand, accompanied by an equal number of Veterans. Music from the National Guard, who performed funeral tunes during the march. Family of the dead. Group of mothers with children. Detachment of the Convention Guard. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Armed federations. Popular societies. Cavalry and trumpets with fourdines. On each side, citizens, armed with pikes, formed a barrier and supported the columns. These citizens held their pikes horizontally, at hip height, from hand to hand. The procession left in this order from the Place des Piques, and passed through the streets St-Honoré, du Roule, the Pont-Neuf, the streets Thionville (former Dauphine), Fossés Saint-Germain, Liberté (former Fossés M. le Prince), Place Saint-Michel and Rue d'Enfer, Saint-Thomas, Saint-Jacques and Place du Panthéon. It stopped front of the meeting room of the Friends of Liberty and Equality; opposite the Oratory, on the Pont-Neuf, opposite the Samaritaine; in front of the meeting room of the Friends of the Rights of Man; at the intersection of Rue de la Liberté; Place Saint-Michel and the Pantheon. Arriving at the Pantheon, the body was placed on the platform prepared for it. The National Convention lined up around it; the band, placed in the rostrum, performed a superb religious choir; Lepeletier's brother then gave a speech, in which he announced that his brother had left a work, almost completed, on national education, which will soon be made public; he ended with these words: I vote, like my brother, for the death of tyrants. The representatives of the people, brought closer to the body, promised each other union, and swore on the salvation of the homeland. A big chorus to Liberty ended the ceremony.

According to Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), civic festivals in honor of Lepeletier were celebrated in all sections of Paris, as well as the towns of Arras, Toulouse, Chaumont, Valenciennes, Dijon, Abbeville and Huningue. Lepeletier’s body did however only get to rest in the Panthéon for a little more than a year, as on February 15 1795, the Convention ordered it exhumed, at the same time as that of Marat. It was instead buried in the park surrounding Château de Ménilmontant, the properly of which the ancestor Lepeletier de Souzy had purchased in the 17th century and that still remained in the family.

One day after the funeral, January 25, Lepeletier’s only child, the ten and a half year old Susanne, who had already lost her mother ten years before the murder of her father, was brought before the Convention by her step-mother and two paternal uncles Amédée and Félix. It was Félix who had held a speech during the funeral and he would continue to work for his seven years older brother’s memory afterwards too, offering a bust of him to the Convention on February 21 1793, (on the proposal of David, it was placed next to the one of Brutus), reading his posthumous work on public education to the Jacobins on July 19 1793, and even writing a whole biography over his life in 1794 (Vie de Michel Lepeletier, représentant du peuple français, assassiné à Paris le 20 janvier 1793 : faite et présentée a la Société des Jacobins).

The president announces that the widow of Michel Lepelletier, his two brothers and his daughter, request to be admitted to the bar, to testify to the Convention their recognition of the honors that they have decreed in memory of their relative. It is decreed that they will be admitted immediately.

One of Michel Lepeletier’s brothers: Citizens, allow me to introduce my niece, the daughter of Michel Lepelletier; she comes to offer you and the French people her recognition of the eternity of glory to which you have dedicated her father... He takes the young citoyenne Lepelletier in his arms, and makes her look at the president of the Convention... My niece, this is now your father... Then, addressing the members of the Convention, and the citizens present at the session: People, here is your child... Lepelletier pronounces these last words in an altered voice: silence reigns throughout the room, with exception for a couple of sobs.

The President: Citizens, the martyr of Liberty has received the just tribute of tears owed to him by the National Convention, and the just honor that his cold skin has received invites us to imitate his example and to avenge his death. But the name of Lepelletier, immortal from now on, will be dear to the French Nation. The National Convention, which needs to be consoled, finds relief to its pain in expressing to his family the just regrets of its members and the recognition of the great Nation of which it is the organ. The Nation will undoubtedly ratify the adoption of Michel Lepelletier's daughter that is currently being carried out by the National Convention.

Barère: The emotion that the sight of Michel Lepeletier's only daughter has just communicated to your souls must not be infertile for the homeland. Susanne Lepelletier lost her father; she must find now find one in the French people. Its representatives must consecrate this moment of all-too-just felicity to a law that can bring happiness to several citizens and hope to several families. The errors of nature, the illusions of paternity, the stability of morals, have long demanded this beautiful institution of the Romans. What more touching time could present itself at the National Convention to pass into French legislation the principle of adoption, than that when the last crimes of expiring tyranny deprived the homeland of one of its ardent defenders and Susanne Lepelletier of a dear father! Let the National Convention therefore give today the first example of adoption by decreeing it for the only offspring of Lepelletier; let it instruct the Legislation Committee to immediately present the bill on this interesting subject. I ask that the homeland adopt through your organ Susanne Lepelletier, daughter of Michel Lepelletier, who died for his country; that it decrees that adoption will be part of French legislation, and instructs its Legislation Committee to immediately present the draft decree on adoption.

This proposal is unanimously approved.

Susanne being adopted by the state would however lead to a fierce debate when, in 1797, this ”daughter of the nation” wished to marry a foreigner. For this affair, see the article Adopted Daughter of the French People: Suzanne Lepeletier and Her Father, the National Assembly (1999)

Right after Barère’s intervention, David took to the rostrum:

David: Still filled with the pain that we felt, while attending the funeral procession with which we honored the inanimate remains of our colleagues, I ask that a marble monument be made, which transmits to posterity the figure of Lepelletier , as you clearly saw, when it was brought to the Pantheon. I ask that this work be put into competition.

Saint-André: I ask that this figure be placed on the pedestal which is in the middle of Place Vendôme... (A few murmurs arise)

Jullien: I ask that the Convention adopt in advance, in the name of the homeland, the children of the defenders of Liberty, who, for similar reasons, could be immolated in the vengeance of the royalists.

All these proposals are referred to the Legislation and Public Instruction Committees.

On Maure's proposal, the Assembly orders the printing of the speeches delivered yesterday at the Panthéon, by one of Michel Lepelletier's brothers, Barère and Vergniaux.

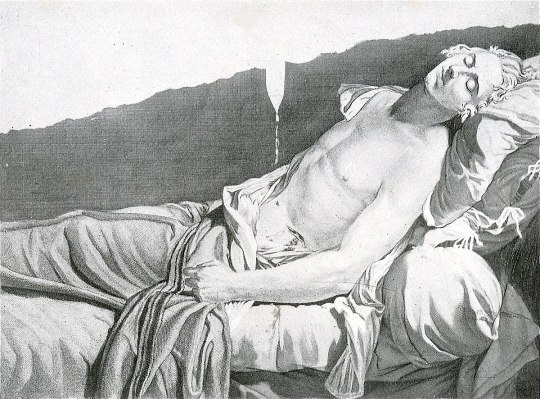

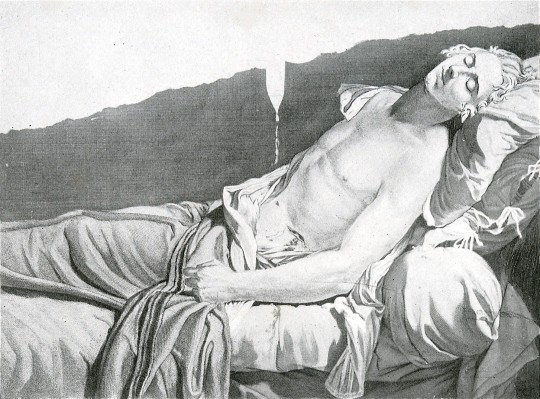

If it would appear David never got to make a marble monument of Lepeletier, on March 28 1793, he could nevertheless present the following painting of his to the Convention, which isn’t just a little similar to his La Mort de Marat.

(This image is an engraving of the actual painting, which has gone missing)

After Marat on July 13 1793 (on the very same day the plan for public education Lepeletier had been working on was read to the Convention by Robespierre) became the second assassinated Convention deputy, we find several engravings etc, depicting the two ”martyrs of liberty” side by side.

In the following months, even more people would be join the two, such as Joseph Chalier, a lyonnais politician executed on July 17 1794 and Joseph Bara, a fourteen year old republican drummer boy killed in the Vendée by the pro-Monarchist forces.

Lepeletier’s murderer, 27 year old Philippe Nicolas Marie de Pâris, a man who the minister of justice described as "former king's guard, height five pieds, five pouces, barbe bleue, and black hair; swarthy complexion, fine teeth, dressed in a gray cloak, green lapels and a round hat” on January 21, went into hiding right after his deed. In spite of his description being published in the papers and a considerable sum of money being promised to whoever caught him, Pâris managed to flee Paris and settled for a country house of an acquaintance near Bourget. He there ran into a cousin of one of the owners. When Pâris asked for food and a bed, he was refused and instead disappeared into the night again. In the evening of January 28 he arrived in Forges-les-Eaux and stopped at an inn, where he came under suspicion once he started cutting his bread with a dagger after which he locked himself into his room. The following morning he woke up with a start as five municipal gendarmes came bursting into his room and told him to come with them. Pâris responded that he would, but in the next second he had picked up his hidden pistol, placed it into his mouth, and pulled the trigger. Searching the dead body, the gendarmes found Pâris’ baptism record (dated November 12 1765) and dismissal from the king's guard (dated June 1 1792), on the latter of which had been written the following:

My certificate of honor. Do not trouble anyone. No one was my accomplice in the fortunate death of the scoundrel de Saint-Fargeau. Had I not run into him, I would have carried out a more beautiful action: I would have purged France of the patricide, regicide and parricide d’Orléans. The French are cowards to whom I say:

Peuple dont les forfaits jettent partout l'effroi,

Avec calme et plaisir j'abandonne la vie.

Ce n'est que par la mort qu'on peut fuir l'infamie

Qu'imprime sur nos fronts le sang de notre roi.

Signed by Paris the older, guard of the king, assassinated by the French.

Learning about what had happened, the Convention tasked Tallien and Legrand with going to Forges-les-Eaux and making sure the dead man really was Pânis. Having come to the conclusion that this was indeed the case, the deputies briefly discussed whether the body ought to be brought back to Paris, but it was decided it would be better if it was just buried "with ignominy.” It was therefore instead taken into the nearby forest in a wheelbarrow and thrown into a six feet deep hole.

Finally, here are some other revolutionaries simping for honoring Lepeletier’s memory just because I can:

…a tragic event took place the day before the execution [of the king]. Pelletier, one of the most patriotic deputies, and who had voted for death, was assassinated. A king's guard made a wound three fingers wide with a saber: he died this morning. You must judge the effect that such a crime has had on the friends of liberty. Pelletier had an income of six hundred thousand livres; he had been président à mortier in the Parliament of Paris; he was barely thirty years old; to many talents, he added the most estimable of virtues. He died happy, he took to his grave the idea, consoling for a patriot, that his death would serve the public good. Here then is one of these beings whom the infamous cabal who, in the Convention, wanted to save Louis and bring back slavery, designated to the departments as a Maratist, a factious, a disorganizer... But the reign of these political rascals is finished. You will see the measures that the Assembly took both to avenge the national majesty and to pay homage to a generous martyr of liberty.

Philippe Lebas in a letter to his father, January 21 1793

Ah! if it is true that man does not die entirely and that the noblest part of himself survives beyond the grave and is still interested in the things of life, come then, dear and sacred shadow, sometimes to hover above the Senate of the nation that you adorned with your virtues; come and contemplate your work, come and see your united brothers contributing to the happiness of the homeland, to the happiness of humanity.

Marat in number 105 (January 23 1793) of Journal de la République Française

O Lepeletier! Your death will serve the Republic: I envy your death. You ask for the honors of the Pantheon for him, but he has already collected the prize of martyrdom of Liberty. The way to honor his memory is to swear that we will not leave each other without having given a constitution to the Republic.

Danton at the Convention, January 21 1793

O Le Peletier, you were worthy to die for your homeland under the blows of its assassins! Dear and sacred shadow, receive our wishes and our oaths! Generous citizen, incorruptible friend of the truth, we swear by your virtues, we swear by your fatal and glorious death to defend against you the holy cause of which you were the apostle; we swear eternal war against the crime of which you were the eternal enemy, against the tyranny and treason of which you were the victim. We envy your death and we will know how to imitate your life. They will remain forever engraved in our hearts, these last words where you showed us your entire soul; ”May my death,” you said, “be useful to the homeland, may it will serve to make known the true and false friends of liberty, and I die content.”

Robespierre at the Jacobins, January 23

Wednesday 23 [sic] — We went to Madame Boyer’s to see the procession. I saw the poor Saint-Fargeau. We all burst into tears when the body passed by, we threw a wreath on it. After the ceremony, we returned to my house. Ricord and Forestier had arrived. I was unable to stop my tears for some time. F(réron), La P(oype), Po, R(obert) and others came to dinner. The dinner was quite fun and cheerful. Afterwards they went to the Jacobins, Maman and I stayed by the fire and, our imaginations struck by what we had seen, we talked about it for a while. She wanted to leave, I felt that I could not be alone and bear the horrible thoughts that were going to besiege me. I ran to D(anton’s). He was moved to see me still pale and defeated. We drank tea, I supped there.

Lucile Desmoulins in her diary, January 24 1793

…Pelletier's funeral took place this Thursday as I informed you in my last letter (this letter has gone missing). The procession was immense; it seemed that the population of Paris had doubled, to honor the memory of this virtuous citizen. The mourning of the soul was painted on all the faces: it was especially noticed that the people were extremely affected, which proves that they keenly felt the price of the friend they had lost. Arriving at the Pantheon, Lepelletier's body was placed on the platform prepared for it; his brother delivered a speech which was applauded with tears; Barère succeeded him. Then the members of the Convention, crowding around the body of their colleague, promised union among themselves, and took an oath to save the country. God grant that we have not sworn in vain, that we finally know the full extent of our duties, and that we only occupy ourselves with fulfilling them! In yesterday's session, Pelletier's daughter, aged eight [sic], was presented to the National Convention, which immediately adopted her as a child of the homeland.

Georges Couthon in a letter written January 26 1793

How could I be so base as to abandon myself to criminal connections, I who, in the world, have never had more than one close friend since the age of six? (he gestures towards David's painting). Here he is! Michel Lepeletier, oh you from whom I have never parted, you whose virtue was my model, you who like me was the target of parliamentary hatred, happy martyr! I envy your glory. I, like you, will rush for my country in the face of liberticidal daggers; but did I have to be assassinated by the dagger of a republican!

Hérault de Sechelles at the Convention, December 29 1793

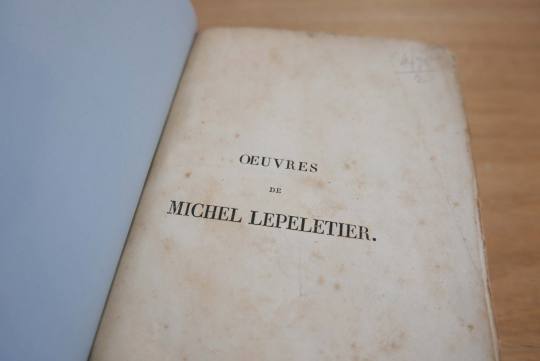

For a collection of Lepeletier’s works, see Oeuvres de Michel Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau, député aux assemblées constituante et conventionnelle, assassiné le 20 janvier 1793, par Paris, garde du roi (1826)

#hérault and lepeletier being bff’s since age six was new information for me#also i think Augustin just found a rival in ”most loyal little bro in the revolution”#frev#michel lepeletier#lepeletier de saint-fargeau#french revolution#ask#long post

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why do you think Michel Lepelletier is forgotten if he was a martyr of the revolution? I never see him talked about here until recently.

This is an excellent question and I don't really know. It sure needs to be researched (and I hope someone did research it) - Lepeletier and Marat were jointly hailed at the martyrs of the revolution during the revolution. Michel was known as the first martyr, and celebrated as such. They knew him and celebrated him during frev. But today, he is not that well known. @saintjustitude gave a good guess as to why it might be - Michel Lepeletier as a class traitor, which goes against the misconception that the revolution exclusively targeted nobles. Even Hérault, who was less principled and not a regicide (and generally more loved by royalists) is kind of forgotten, let alone someone like Michel Lepeletier. He simply doesn't fit the narrative we have of the revolution.

So yes, that theory makes sense to me, but I admit I did not read about any specific work/sources on the topic. Maybe there are other factors (I've read about Michel's daughter being a royalist and wanting to destroy traces of her father's revolutionary image, including destroying David's painting about his death). So maybe there was a conscious attempt to erase Michel from revolutionary memory? I admit I don't know how his legacy was handled during the 19th century. If anyone knows, please share!

As for why he isn't talked about more around here... I think there are some posts from time to time but true, he is not featured prominently. (Which needs to change, imo. I am first guilty as charged for kind of ignoring him previously. Which I intend to change).

It might be that he died relatively early, so most of his contribution is about early part of the revolution, which we discuss less on frevblr. For example, his work on the Penal Code of 1791. It could also be - and I don't know how else to put it because I know it's not always a factor here, but it definitely is a factor at least some time - he wasn't particularly good looking, and there are no "fun" scandals surrounding him. So, not easy to make shitposts. (Nothing against shitposts! My blog is half those, half srs discussion). So maybe he is perceived a bit boring/uninteresting?

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

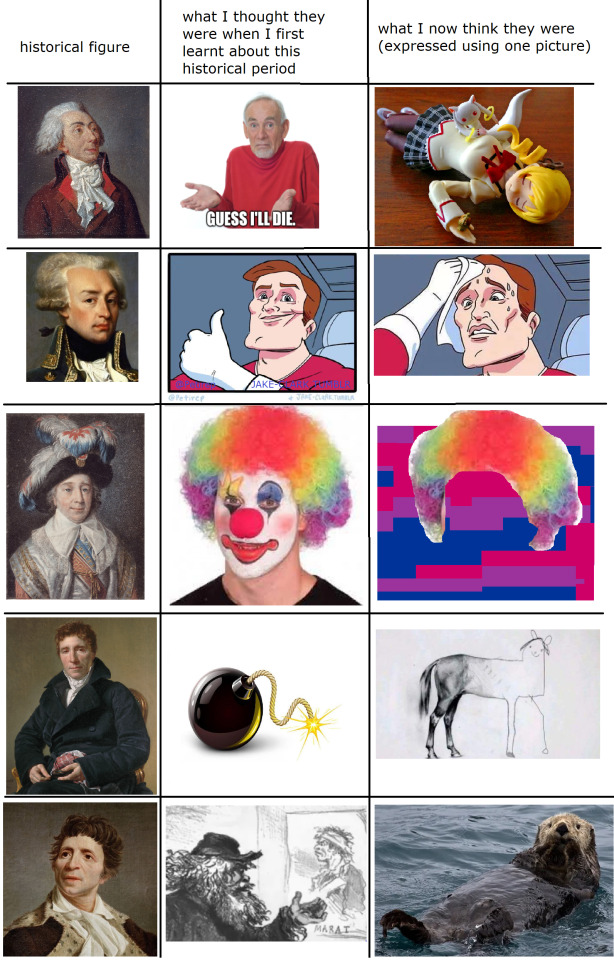

I prefer otters.

#frev#french revolution#here is hoping the comparison between mami sempai and michel lepeletier is not as cursed as it appears#i have another chart like this for female frevolutionaries but that one has even more anime comparisons#yes i am aware of the cringe of it all but i have repented and am actively working to make it cringier

72 notes

·

View notes

Note

have you played assassins creed unity?

Not yet, but a friend of mine who is a Lepeletier (a radical ex-aristocrat revolutionary who was assassinated by a Gardes-du-Corps. The assassin orginally targeted Philippe Égalité but then went for Lepeletier, who was quite famous for his fixed daily routine, because both he and Philippe Égalité voted for the death of Louis XVI.) fanboy told me that the game made Lepeletier one of the targets and let him die a manly-father-manly man …… I laughed for 5 minutes straight…… 🤣

#I've also seen that Jacques Roux is in the game#I am expecting the worst#frev#Louis-Michel le Peletier#Lepeletier#instead of being alive and in pain with a open gut for half a day before death he died quick and clean in the game tho#french revolution#assassin's creed

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

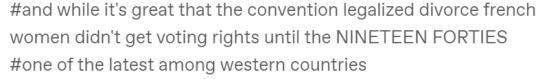

Jacques-Louis David - The last moments of Michel Lepeletier, 1793.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

in your opinion, what was the most significant mistake the jacobins ever made? (i tend to like them much more than other factions in the frev, but i still want to know how Problematic my Faves were)

Good question. I'm not sure which period you want to talk about regarding the Jacobins, so let's discuss the one after the fall of Louis XVI's monarchy. I will mainly encompass the Mountain faction.

Regarding tactical errors, according to some historians, including Antoine Resche, a contemporary historian who has made excellent videos on the French Revolution under the name Histony, which can be found on the Veni Vidi Sensi website, leans towards the lack of left-wing unity as one of the errors. And honestly, he's not wrong. Some might think that the elimination of Danton and the Hébertists was a turning point. But it was salvageable (I've already discussed what I thought in one of my posts). Only the Jacobins made the grave mistake of eliminating Chaumette, among others, even though he had refused to participate in an attempt to overthrow the Convention, which showed he was the most reasonable. Keeping him as the prosecutor of the Commune would have appeased some of the sans-culottes. Instead, the Convention has him arrested and executed. I understand that at that time the Convention could not afford an overthrow and was afraid Chaumette might change his mind, but by doing so, they alienated a large part of the sans-culottes. The wave of executions like Gobel or Chaumette was one of the most disastrous moves.

Another one is the non-application of the Ventôse laws, but it is true that some Montagnards blocked this, and the Marais was against these laws.

Also, being a fervent advocate of freedom of expression, there should never have been decrees holding journalists accountable. I don't particularly like Desmoulins, but executing him for his writings… Moreover, it will not prevent opinions from forming and solidifying.

Regarding moral errors: In addition to the travesties of justice I mentioned concerning the Hébertists and the Dantonists, there were other cases. When Girondin deputies were dismissed, most deputies did not want them dead, let alone imprisoned. They were only supposed to remain under house arrest. The problem is, many of them escaped and incited uprisings in the departments, which further exacerbated the already endangered Republic. Despite all I have to reproach them for, some Girondins were honorable people, notably Manon Roland and Vergniaud (even if Vergniaud had an ambiguous attitude, he still remained under house arrest) who stay in Paris. Yet they were judged, condemned to death, and executed along with other Girondins who incited or attempted uprisings and fled Paris. It wasn't even a tactical error; it was unfair.

Another very minor point concerns the Convention entirely, and this is my opinion. Why separate Marie Antoinette from her son? I understand there were royalists in Paris (the assassination of the remarkable Louis Michel Lepeletier by one of Louis XVI's former guards, among other events, will demonstrate this) who would do anything to get their hands on him as Louis XVII, which would have been dangerous. It would have been better to monitor the child's education closely given this context, but why not have strict supervision while leaving him in his mother's care, even though we know her opinions? I don't want to demonize Antoine Simon, executed in Thermidor; he wasn't a brute; he had compassion for the former queen and liked the child, but it's horrible. Being myself a proponent of reforms for jail to ensure the child remains very close to his parents, I protest against this. And the royalists seized upon it to portray an image of an inhumane Republic.

Women's rights were not respected, as I discussed in my post "Women's rights suppressed."

One of the most serious errors was the Prairial Law. When this bill presented by Couthon and later approved by the Committee of Public Safety and voted on by the Convention passed, many innocents suffered. Following the execution of the "Robespierrists," the Convention lied, saying it had not approved it, which was false.

Paradoxically, there was no internal elimination necessary at that time, notably the case of Carnot, who gave orders behind the backs of others to wage a war of conquest, which would have jeopardized the Battle of Fleurus if Saint-Just had not intervened with the order. I don't understand why he wasn't arrested; generals have been executed for less than that. This man doesn't deserve his title as the organizer of Victory, but having eliminated those who had really done the job like Saint-Just, among others, he could claim that title.

I realize I have done a critical job on the Montagnards even though I admire them, so a few lines to rehabilitate them. Most of them refused the irresponsible war of conquest advocated by the Girondins. Finally, fatigue was fatal to them. They put their best efforts into saving France, but most became ill (Couthon, Robespierre; I don't know if Billaud-Varenne was beginning to develop his dysentery or if his illness came after his deportation). Robespierre made a grave mistake by slamming the door on the Committee of Public Safety following a dispute among its members, then a few weeks later making a speech where he designated culprits without naming names (like Fouché, for example), so some wrongly believed they were the ones being designated when they weren't. Fouché and his gang played on this.

I want to say that Jean Clement Martin explained that if the Girondins are seen as victims, it's because they didn't have time to put the Montagnards on the guillotine. There were quite a few assassinations of Montagnard deputies (some think that Barbaroux manipulated Corday to kill Marat, Joseph Chalier was killed in atrocious conditions by the Girondins of Lyon, Isnard's speech). When the Jacobins acted, there was an internal civil war and an external war against the Revolution, plus a depreciated currency. And they saved it. For a while, they tried to accommodate (at least the majority of them) their adversaries. Then the gloves came off. But they remained in democracy, even in the worst moments. The Jacobins supported the abolition of slavery (not just them), and most of the major Jacobin figures fully supported the uprisings by slaves against the colonists.

Napoleon, although praised today for inheriting a better situation thanks to the efforts of his predecessors, through his dictatorial attitudes, betrayal of the Jacobins, and wars of conquest (all the wrong things), left France in a worse state with the return of the Bourbons. Revolutionaries like Marat predicted from the outset of the French Revolution that if the Girondins persisted in declaring war, even if France were victorious, there would be a military dictatorship and subsequently the return of the Bourbons.

All this leads me to think that it was the revolutionaries of the Mountain who were pragmatic and Napoleon the "idealist" in the wrong sense of the term, given his grandiosity and stupid belief (in my opinion) that he could impose hereditary dictatorship, exploit other countries without them retaliating (but that's another story).

Finally, the Jacobins in power were exhausted; they even lacked sleep hours due to their internal schedules. Before the Prairial Law was passed, there was an assassination attempt on Collot, so it was thought that the royalist danger was present. Plus, this law was disfigured by those who presented it; they thought they would only use it against people like Fouché, Carrier, Barras, Fréron, Tallien—des despicable men who dishonored France and the Revolution. It was they who later presented themselves as victims of the Jacobins when they were the worst during the Terror. Contrary to belief, heads rolled after the Terror; just look at the execution of Romme and the other Montagnards, the execution of Babeuf, the fact that anyone who demanded the constitution of 1793 could be punishable by death.

Finally, I want to say that despite my speeches, I don't believe in providential men; if France could have a sense of greatness during this period, it's thanks to the people. In Algeria, we have the slogan: "One hero only: the people."

#frev#french revolution#Roland Manon#Gironde#Montagne#jacobin#Terror#Fouché#Saint Just#Carnot#Robespierre#couthon#Romme Charles#Babeuf#Vergniaud#chaumette#camille desmoulins#marat#napoleon#georges danton#tallien

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

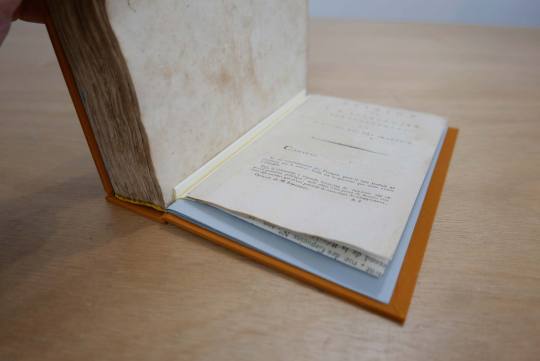

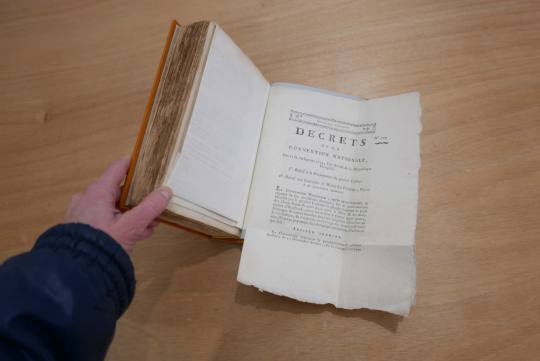

Restauration "Oeuvres de Michel Lepeletier"

Débrochage, réparation des fonds de cahiers, couture sans ébarbage, bradel dos droit avec étiquette sur plat avant qui reproduit la page de titre

Ajout de planches séparées en montage sur onglet en fin d'ouvrage, dédoublage des macules utilisées pour l'ancienne couverture

22x12x3,5cm

0 notes

Quote

M. Le Pelletier-Saint-Fargeau, rapporteur. Voici l’article 7 :

« La peine de la chaîne ne pourra excéder vingt années. »

M. Prieur. Cette disposition me paraît infiniment juste. [...] Nous devons donc, Messieurs, imiter la sagesse de l’ancienne loi et dire que les peines ne seront pas perpétuelles ; d’ailleurs c’est concourir au but moral du comité, qui n’a jamais vu dans les peines que l’espoir d’amender les hommes ; je demande donc que l’avis du comité soit adopté.

Assemblée constituante, débat sur le code pénal, 3 juin 1791 (AP, t. XXVI, p. 722).

Finalement l’article sera adopté sous cette forme : « La peine de la chaîne ne pourra, en aucun cas, être perpétuelle. »

#on se doute bien que même 19 ans seraient de trop#les misérables#Prieur de la Marne#Révolution française#il y a 227 ans#3 juin 1791#1791#Assemblée constituante#Louis-Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau#Pierre-Louis Prieur

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Derniers Moments de Michel Lepeletier

(engraving by Tardieu after David's painting, now lost)

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

long post, because i'm confused and need help from my mutuals.

this. this really confused me. more well-read mutuals help me if you can:

i'm mostly sure "suggesting a constitutional monarchy" was not the sole reason de gouges was arrested, tried, and executed, and it could not be the main reason. jean-paul marat was once a supporter of constitutional monarchy. Supplément de l’Offrande à la patrie did end with a message of hope for louis xvi to sort every grievance out while still being king. (and it was not just marat, this support for constitutional monarchy was widespread before louis xvi made the questionable decision to attempt to flee the country.) de gouges was executed after louis capet was, and the possibility of having a constitutional monarchy by then was certainly not as high.

i'm not so sure about what is meant by "anarchist beheadings". beheading as a method of execution is not anarchist on its own. beheading existed before frev, as did many, many other types of executions. the english did in ireland some of those other types of executions during the last 10 years of the 18th century, that is to say, at the same time as the frev happened. and we do not use the word "anarchist" to describe english attempts at disproportionately criminalising the irish. so putting the word "anarchist" immediately next to "beheadings" is something i genuinely cannot figure out on my own.

national assembly (20 Jun - 9 Jul 1789),

national constitutional assembly (the one that michel lepeletier worked in, 9 Jul 1789 - 30 Sep 1791),

legislative assembly (the one that made divorce far more accessible than before, 1 Oct 1791 - 20 Sep 1792),

and the national convention (21 Sep 1792 - 26 Oct 1795).

i don't think there was 1 position on the rights of women in any of these four. afaik the jacobins themselves were divided on how much social equality women could achieve. and the brissotins made the questionable decision to declare war on austria, which did not just mean that a very disorganised army was to be put into action, but that working-class women's lives were then affected by inflation and possible hoarding-and-profiteering of grains and of necessities.

again i have much more reading to do on this one.

many more women (e.g. louise-renée leduc, claire lacombe, pauline léon, théroigne de méricourt, félicité fernig, théophile fernig) had more stakes in the frev than de gouges did. often they would put their very lives on the line. their perceived femininity was not their primary concern, e.g. the fernig sisters kept being soldiers even when other soldiers were aware that they were women.

maybe as a tangent: mary wollstonecraft, despite her criticism towards the frev, was still much, much more welcoming of the frev than her theoretical opponent, edmund burke, and her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman was translated into french within a year of being published. wollstonecraft lived in paris from 1792 to 1795, and was not persecuted (partly due to the protection of an american man, but still if any suspicion came upon wollstonecraft, it would be because she was english, not because she was a woman or a feminist thinker).

with the exception of leduc, every woman mentioned here died after 1793. now i am aware that this is a small sample size, and misogyny definitely existed during the 18th century (not surprisingly), but i cannot find in any primary source evidence suggesting the existence of a systematic exclusion of outspoken women or women of action or feminist thinkers.

i am aware that suffrage and/or being part of the national assembly (later national constituent assembly, later legislative assembly, later national convention) were not the only ways of participating in politics. working-class women in the 18th century not having the right to vote was sad when compared to working-class women in the 21st century having this right. but they were allowed to influence the men in their communities to vote, which was fortunate when compared to the lack of the right to vote in general in the old regime.

my general grasp so far is that, any kind of written or spoken output during the frev had very real risks attached, because literacy was quite low, and many "readers" of newspapers or pamphlets heard the contents by others retelling what was read out at cafés. spreading misinformation, or using gross invectives as marat called it, was not just unhelpful, but possibly damaging to the organisation of the urban poor.

now personally i do not believe that de gouges deserved to be executed, but that is because i do not believe anybody deserved or deserves to be executed. (that's for a different post.)

if male journalists such as hébert were losing their lives for misleading their readers and for unnecessary verbal violence, however, then de gouges being subjected to similar levels of scrutiny was a sign of equality -- for men and women of letters at the very least.

voting rights for women being granted only in the 1940s was

a) still a good thing. that it happened at all was a good thing. that it is still here is a good thing.

and

b) the result of feminist thoughts coinciding with economic and political realities. between the frev and the 1940s were three republics and two empires, and it would be reductive to blame what was delayed until the 1940s solely on the frev. feminism, as a group of schools of thoughts, did not doom itself because de gouges died.

and

c) still not equality yet. voting allows, but only allows, more women to think about the state that exercises disproportionate power over them, and to describe this state, and to study this state. i am reminded of a quote from dear Karl here.

33 notes

·

View notes

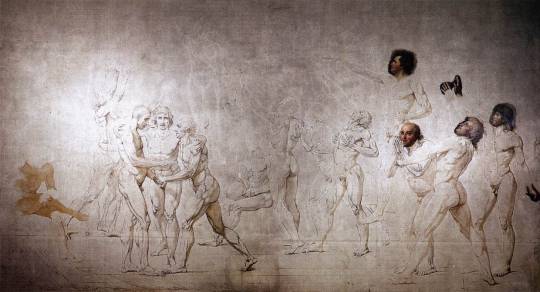

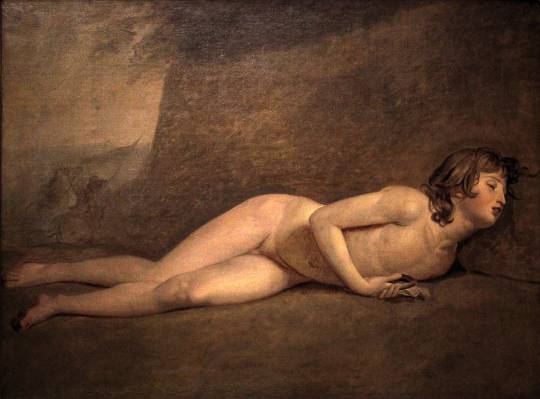

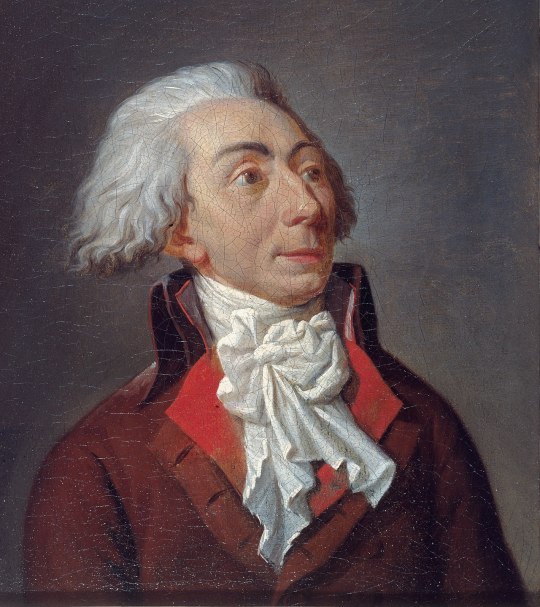

Photo

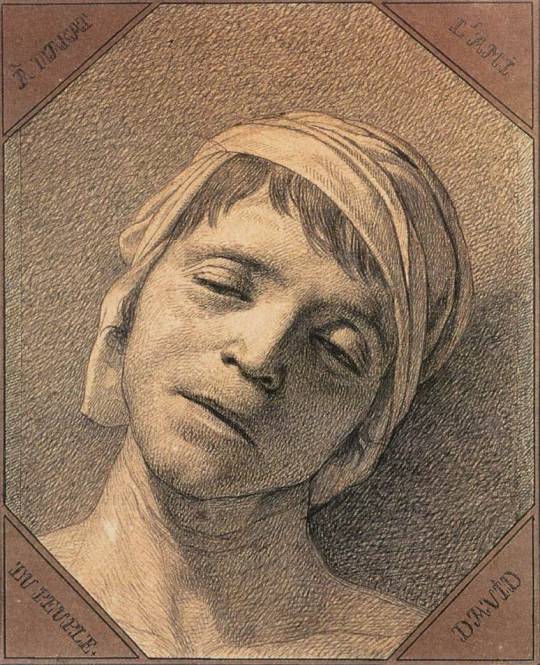

Jacques-Louis David 1748-1825

His favorite subjects during Revolution being dead (or almost dead) people and/or naked guys.

I added a picture of David making a picture of Marie-Antoinette as a bonus.

1. La Mort du jeune Bara, 1794 (incomplete), Musée Calvet - he was a drummer in the Army of First Republic, killed by the Vendéens

2. Tête de Marat assassiné, dessin d'après nature, 1793

3. Marie-Antoinette conduite à l'échafaud, 1793, Musée du Louvre

4. Le Serment du Jeu de paume (incomplete) 1790-1794, Musée national du Château de Versailles (a naked Robespierre, YES)

5. Les Derniers Moments de Michel Lepeletier, 1793 (he was the guy assassinated for voting for death of Louis XVI and therefore considered a martyr )

6. Jean-Emmanuel Van den Bussche, Le Peintre David dessinant Marie-Antoinette conduite au supplice, 1900 Musée de la Révolution française,château de Vizille.

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacques Louis David - The death of young Bara.

The Death of Young Bara, Joseph Bara or The Death of Bara is an incomplete 1794 painting by the French artist Jacques-Louis David, now in the musée Calvet in Avignon.

Joseph Bara, a young drummer in the army of the French First Republic, was killed by the Vendéens. He became a hero and martyr of the French Revolution and – with The Death of Marat and The Last Moments of Michel Lepeletier – the painting formed part of a series by David showing such martyrs. There is also an anonymous contemporary copy dating to 1794, now in the Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille and exhibited at the Musée de la Révolution française.

Versions >> 1 | 2

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi!

I have a question regarding the investigation story. So Tallien and Legendre found the birth certificate of Pâris on the body, but even if he was Pâris, why would he have his birth certificate with him? Did people usually carry it with themselves? Did they use it kinda like an ID?

Oh lol, now I see that I keep saying "birth certificate" when I meant "baptism record". And I am not sure if one would typically have that - the originals were in church records, but maybe parents received a copy? Does anyone know?

The only example I can think of is SJ, who said that he didn't have a proof of his date of birth back when he claimed he was 25 while being 24. And it seemed like a legit excuse, because the only proof of his birthday was a baptism record from a church in Decize.

With Pâris, he was actually trying to flee France for England, so maybe he collected his documents? I would assume that he'd need a passport, which is not mentioned among the documents found on the dead man. (Now that I think about it, if Pâris did fake his death he would want to keep the passport so he could flee France, so maybe that's why it's not found on the dead man).

But all in all, IDs in the modern sense have only starting to appear; 18th century people didn't have generalized IDs the way we do now (which is why you have all those stories about people changing/faking identities). The revolution introduced some measures in terms of identification, but am not sure how the ID situation was in early 1793, nor would Pâris obey the regulations about that. I know people in Paris were required to have a Carte de sûreté, but he probably avoided?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Gemini Power Revisited" - A Shitpost

You known the whole talk about "Gemini power" (Fouché plus Collot)? Well, I realized yesterday that Michel Lepeletier was also a gemini. (Born on 29 May 1760). And we know Marat was, too.

So, I propose a revisited, better Gemini power combination that will put C & F to shame.

Disclaimer: I don't believe in astrology in any way, shape, or form. This is a shitpost.

#it's a shitpost about me learning lepeletier's birthday#which is not of importance - they didn't pay attention to birthdays much#but i like having a day to talk about people#and birthday is more apropriate than a death day#except for fabre who was born on 10 thermidor#fun#frev#michel lepeletier

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

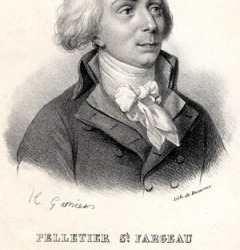

Michel and Félix Le Peletier

I need to read more about them. If anyone has book recommendations, please let me know!

13 notes

·

View notes