#remix making art and commerce thrive

Text

Copy(right) and Copy(wrong): Defending Fair Use, Protecting Ourselves and Our Students

As Janice Walker notes in Copy-rights and Copy-wrong, it’s so easy to save information and media files nowadays that we forget that what’s easily obtained wasn’t always meant to be publicly available. There are those, like Lawrence Lessig, who would argue that “information wants to be free”, and that we shouldn’t set up a legal system to criminalize things we know people will do anyway and that, ultimately, aren’t harming anyone. But, as much as I might be tempted to agree (so long as we make a distinction between huge conglomerates arbitrarily extending copyright every fifty years and individual artists, creators, and small businesses trying to make a living), I’m more immediately concerned with how I can teach students to protect themselves when using media for class or otherwise. The most common tool given to help prevent students from running afoul of copyright is these four principles for determining fair use:

What is the purpose of the use? Educational, nonprofit, and personal use are more likely to be considered fair than is commercial use.

What is the nature of the work being used? In most cases, imaginative and unpublished materials can be used only if you have the permission of the copyright holder.

How much of the copyrighted work is being used? If a writer uses a small portion of a text for academic purposes, this use is more likely to be considered fair than if he or she uses a whole work for commercial purposes.

What effect would the use have on the market for the original? The use of a work is usually considered unfair if it would hurt sales of the original.

(Maimon et al qtd. Westbrook 167)

Of course, these four principles are only a heuristic, and people can and do face copyright strikes for use that follows all four of these principles when they use material in a way the copyright holder doesn’t like. For that reason, Steve Westbrook argues, we shouldn’t take our concern with copyright to extremes.

By asking for permission to use copyrighted material even when we are reasonably confident it falls under fair use, we forfeit an opportunity to “deny ultimate power to holders of derivative rights, to recover a sense of agency and authority for the writer who relies on appropriative practices, and to counter abuses of copyright law (Westbrook 166).”

Janice Walker offers a few additional, more specific considerations for using copyrighted material in online spaces that can help students build multimedia projects with confidence (Walker 214):

1. Follow guidelines already established for published (i.e., print) sources, if possible. In other words, if you’re using textual materials (i.e. book excerpts or articles) where this would make sense.

2. Point to (i.e., link to) images, audio, and video files rather than downloading them, if possible. While I admire the intent behind this recommendation, to preserve as much context and ‘paper trail’ as possible, I do wonder if it could create accessibility concerns for disabled visitors/viewers/readers/participants, especially those using screenreaders.

3. Always cite sources carefully, giving as much information as possible to allow the user to relocate the source.

4. If in doubt, ask. In doing so, be sure to explain exactly what and how much you intend to use and what you intend to use it for.

She also argues that, as composition teachers, we have a particular obligation to use media mindfully and to educate other teachers and scholars about copyright. In the spirit of taking up that challenge, I reproduce here an account of the rules laid out in order for something to be considered fair classroom use under the TEACH act (Reyman qtd. Walker 209-210):

Use is limited to works that are performed (such as reading a play or showing a video) or displayed (such as a digital version of a map or a painting) during class activities. The TEACH Act does not apply to materials for students’ independent use and retention, such as textbooks or articles from journals.

The materials to be used cannot include those primarily marketed for the purposes of distance education (i.e., an electronic textbook or a multimedia tutorial).

Use of materials must occur “under the actual supervision of an instructor”.

Materials must be used “as an integral part of a class session.”

Use must occur as a “regular part of the systematic mediated instructional activities.”

Students must be informed that the materials they access are protected by copyright.

Further, it remains incumbent on faculty and/or administrators to ensure that the following restrictions are adhered to:

limiting access to material to only those students enrolled in the class;

ensuring that digital versions are created from analog works only if a digital version of the work is not already available;

employing technological measures to “reasonably prevent” retention of the work “for longer than the class session”;

developing copyright policies on the educational use of materials; and

providing informational resources for faculty, students, and staff that “accurately describe, and promote compliance with, the laws of the United States relating to copyright.”

Reading these guidelines in full motivates me to talk to my department head and seek out more detailed explanations from the federal government, because per these guidelines I’m pretty sure uploading a chapter of a copyrighted text for students to read for homework, which I and every teacher I know do all the time, wouldn’t be fair use because it’s not “under the actual supervision of an instructor”.

#week 7#copyright#TEACH act#fair use#walker#westbrook#lessig#copyrights and copywrongs#remix making art and commerce thrive#what we talk about when we talk about fair use

0 notes

Text

Blog 3 - COM 311

Lawrence Lessing: “Remix: how creativity is being strangled by the law', The Social Media Reader

In Lessing’s book ‘the social media reader’, the chapter “Remix: how creativity is being strangled by the law” explains how copyrights limit society to be creative and create their own ideas. Because when someone does the copyright of another person's work, it's a duplication of the work but slightly modified. Also talks about the difference between digital property and physical property. Lessing recognizes that the law of physical property cannot be applied to the digital sphere because it is in two different circumstances.

In 1976 the US Copyright Act was released for which software started to be protected and licensed under copyright law. Therefore so many, companies started losing their work, because copyright was not allowed anymore. There is no possibility to create content for the industry or anyone because it was a matter of being privileged and professional.

Lessing, with a moderate perspective, explores copyright acknowledging that it needs an update. The author points out the distinction between the culture of the 20th century and the culture of the 21st century. The culture of the 20th century can be defined as a read/only culture, which is a metaphor to express the kind of culture that period in which creativity is only consumed. The culture of the 21st century can be defined as a read/write culture in which users became also content creators. This metaphor refers to a massive social change where the users become consumers and producers. Copyright law, is still present today, especially in the music industry. A musician cannot, make a similar sound or even lyrics that it is considered to be copyrighted and thus troubles the artist creating a conflict.

This slogan that I found while searching for the copyright law in today’s society literally gave this image. I do believe that we are all copyright users and owners at the end of the day, especially in the 21st century where social media is so public.

Lawrence Lessing: Remix! Making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy

In this book, Lessing goes deeper into the idea of sharing economy we have read about the copyright, and in the Remix making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy, we will see another perspective on the hybrid economy. When a person talks about the economy, is about money, but in this book Lessing explains the different faces of sharing economy.

So, he first starts telling his encounter with a young man that had a collection of movies, on a portfolio. Lessing was amazed by how many movies this young guy had. Therefore, he came to the conclusion that that was a ‘stolen’ movie, meaning that the young boy had downloaded those movies with no consent from wherever he got it from. Therefore, since we saw before that the law of copyright was applied, and we see the boy full of DVDs, the man asks to rent one from him instead the boy gifts him it.

Therefore, I understood from the reading that sometimes money-exchanged are more dangerous, and sometimes illegal, thus sharing the economy is the best opinion for people to come along together. According to Lessing, the foundation of the sharing economy is the notion that the trade would eventually be fair. Nevertheless, in today's hybrid economy is still a massive disparity and completion between sharing economy and the commercial economy.

0 notes

Link

As the number of abandoned storefronts and closed retail outlets continues to mount, the once unremarkable activity of shopping at brick-and-mortar stores can feel like reality askew — like a stroll through the Twilight Zone. As this glum new normal becomes, well, the norm, signs of life can be almost as jarring.

Take, for instance, a pair of storefront windows on Beverly Boulevard in West Hollywood. Just recently they were lifeless reminders of an upscale furniture store, now defunct. Then, in August, they began to fill with seemingly unconnected objects: bluejeans piled in a chest-high mound, a lounge chair upholstered in denim, a mannequin in a jumpsuit with an eyeball for a head standing amid a sea of paint-splattered drop cloths.

Hand-painted signage in the other window offered only that this “Appointment Only” storefront with the cryptic displays, and the 6,000 square feet of retail space behind them, are the domain of Gallery Dept.

Despite the name, Gallery Dept. isn’t a gallery or a department store but a hybrid clothing label that sits somewhere in the Venn diagram overlap between street wear label, denim atelier, neighborhood tailor and vintage store. Just as accurately, you could call Gallery Dept. the personal art project of its founder Josué Thomas, a designer whose own creative urges are just as disparate and layered.

With so many small brands in a state of retreat this summer, Mr. Thomas’s label has not only weathered these spirit-crushing conditions but thrived. In less than two years, Gallery Dept. has moved from a crowded workshop a few blocks down Beverly Boulevard to its new space in part because its hoodies, logo tees, anoraks and flare-cut jeans — each designed and hand-painted by Mr. Thomas on upcycled or dead-stock garments — have become unlikely objets d’art in a crowded street wear market.

This corner of the fashion industry is a crowded one, and in recent years there have been a glut of collaborations and merch drops that have taken on a corporate cadence. In contrast, Gallery Dept. is something of a bespoke operation, offering street wear basics that are blessed with an artist’s (in this case Mr. Thomas’s) singular touch.

Mr. Thomas began to cut jeans and screen-print shirts as the mood struck in 2017, and since that time Gallery Dept. has grown from an underground cult label for collectors to one with atmospheric clout after being worn by Kendall Jenner, LeBron James, Kendrick Lamar and two of the three Migos (Offset and Quavo).

Those lucky enough to enter the appointment-only space, now booked with up to 20 appointments a day, are greeted inside by a 20-foot-tall span of wall that reads, “Art That Kills” in a large crawl text, and the occasional reference to Rod Serling’s seminal sci-fi program.

Throughout the sunlit store, Mr. Thomas’s abstract paintings and writings fill the spaces between clothing racks and bright brass shelves heavy with the brand's thick hoodies and sweatpants. Over the chug of sewing machines, one can hear snippets of bossa nova Muzak, a vinyl-only mix also made by Mr. Thomas. (There are also plans to release music by other artists, including the New York rapper Roc Marciano, under an Art That Kills imprint.)

Gallery Dept.’s new space was financed on the strength of e-commerce sales from this past spring, and not with the help of venture capital or outside investors, Mr. Thomas said on a recent walk-through. This freedom gives him and the label, which now employs 12 people, the freedom to operate on its own esoteric terms. And there are a few. In the store’s dressing rooms, there are no mirrors to survey a fit. (“We’re going to tell you if a piece works or not,” he said.) Nor are there price tags on its garments.

“If the first thing you look at is the price, it’s going to alter your thinking about a piece,” he said. “I’d rather people engage with the clothing first.”

The Gallery Dept. does not indulge pull requests from stylists or send its pieces to influencers, a practice Mr. Thomas explains with a trace of punk indignation.

“Kendall doesn’t get a discount,” he said. “We don’t seed. I don’t care who it is — we don’t cater to different markets.”

Wearing cutoff carpenter pants and a white T-shirt, each dusted in a fine rainbow splatter, Mr. Thomas looked every bit like an artist roused from his creative flow, complete with paint-stained hands and individually colored fingernails. Standing in a mauve-carpeted room, Mr. Thomas pointed out his latest ideas: pewter jewelry in eccentric shapes, like an earring in the shape of a zipper pull, made in collaboration with the Chrome Hearts offshoot, Lone Ones, and shorts cut from dead-stock military laundry bags — while explaining the origins of his own style.

“I liked my parent’s clothing growing up,” Mr. Thomas said. “As a teenager, I was able to fit into my dad’s leather jacket. The beat-up patina on it was perfect, and I realized that that was personal style. It was something you couldn’t go to a store and buy.”

Mr. Thomas, who turned 36 in September, never studied fashion or garment making, and he can’t work a sewing machine. But growing up as the son of immigrants from Venezuela and Trinidad, he watched as his parents subsisted on their raw artistic skills to create a life in Los Angeles. And he now uses those same talents as an artist and designer: sign-painting, tie-dying, screen printing. For a short time, his father, Stefan Gilbert, even ran a private women’s wear label.

Similarly, in his early 20s, Mr. Thomas worked at Ralph Lauren. As one of the few Black people in creative roles in a predominantly white company, he soon realized that the only way to survive in the fashion industry would have to be with a project of his own making.

“I was the ‘cool’ Black guy, but there was nowhere for me to go,” he said. “Best case would have been sourcing buttons for women’s outerwear or something.”

Gallery Dept.’s spontaneous inception came about in 2016 when Mr. Thomas sold a hand-sewn denim poncho off his own back to Johnny Depp’s stylist. At the time Mr. Thomas was focused on making beats and D.J.-ing, but after selling all of the pieces he’d designed for a small trunk show at the Chateau Marmont, he realized he’d discovered a new creative lane.

It had less to do with ponchos, which were dropped from subsequent collections, and more to do with old garments being remixed in the heat of artistic paroxysm, with as little second-guessing as possible. With the help of Jesse Jones, a veteran tailor, Mr. Thomas began churning out made-to-order pieces for customers who often were unaware of what, exactly, they had stumbled into.

“We were creating pieces while we were selling them,” he said.

Working with heavy vintage shirts, hoodies, trucker hats, bomber jackets, whatever was at hand, Mr. Thomas would frequently screen-print the brand’s logo, adding paint or other flourishes as the feeling struck.

Today that extends to long-sleeve tees, sweatpants and socks. At the time, he also began blowing out the silhouette of vintage Levi’s 501s and Carhartt work pants into a subtle flare, accented with patches and reinforced stitching, resulting in a streetwise update of the classic boot-cut jean.

Mr. Thomas christened this style of jeans the “LA Flare.” And where denim has so historically hewed to “his” and “her” categories, the LA Flare is the zeitgeist-y “they” of street wear denim. (The label labels its items as “unisex.”)

The jeans come with a luxury item’s price tag, with a basic version starting at $395. Custom tailoring and additional touches by Mr. Thomas, can push the price upward of $1,200. One early collaboration with Chrome Hearts, a pair of orange-dyed flares patched with that brand’s iconic gothic crosses, has gone for $5,000 on Grailed.

“There is nothing like Josue’s repurposed jeans,” said George Archer, a senior buyer at Mr Porter. “They are both a wearable piece and a work of art. No one else is doing what he’s doing.”

For Mr. Archer, who first noticed the Gallery Dept. logo popping on men in Tokyo in March, Mr. Thomas “interprets and creates” clothing as if it was an end in itself — and not a commodity to be monetized. (Nonetheless, Mr Porter hopes to monetize a collection of Gallery Dept. pieces via its e-commerce site later this year.)

“You can feel the warmth of Josue’s hands on each of the pieces,” said Motofumi Kogi, the creative director of the Japanese label United Arrows & Sons. An elder statesmen of Tokyo’s street wear scene, Mr. Kogi found the label on a trip to Los Angeles last year. It’s not only Mr. Thomas’s artistic touch that stands out to him but his vision for remaking a staid garment into something that Mr. Kogi believes has not been seen before.

“He took this staple of hip-hop culture and refreshed it,” he said, referring to Carhartt pants.

Getting the people who make that culture to buy in was another matter. “The first year we did the flare, in 2017, skinny jeans were in,” Mr. Thomas said. “Rappers would come into the shop and say they’d never wear a flare. Now, everyone is wearing it.”

On Instagram, fit pics by rappers like Rich the Kid, along with the aforementioned Migos, Quavo and Offset, Gallery Dept.’s flare has become a familiar silhouette, skinny jeans breaking loose below the knee, usually coiled up at the ankle around a pair of vintage Air Jordans.

One fan of the jeans, Virgil Abloh, sees Mr. Thomas’s “edit” of the classic garment as the next chapter of its history.

“Their flare cut is the most important new cut of denim in the last decade — since the skinny jean,” Mr. Abloh said. A self-described Levi’s “obsessive” who owns more than 20 pairs of Gallery Dept. jeans, he walked into Mr. Thomas’s workshop one day after a routine stop at the Erewhon Market across the street.

“I thought: ‘This is amazing. Here’s some guys editing their own clothes in a shop,’” he said. “It reminded me of what I was doing when I started out, painting over logos, making hand-personalized clothes.”

Mr. Abloh considers Mr. Thomas’s work to be the fashion equivalent of “ready-made” art, and he offers Shayne Oliver of Hood by Air as a distant contemporary. He suggested that he and Mr. Thomas come from a lineage of Black designers that is still in the process of defining itself.

“He’s a perfect example of someone creating their own path from a community that hasn’t traditionally participated in fashion,” Mr. Abloh said. “I see Josue as making a new canon of his own, showcasing what Black design can do.”

Mr. Thomas didn’t argue with that. But he was also a little preoccupied with whatever was taking place at the tips of fingers to get lost in the thought. The future of his brand, after all, depends on his ability to stay in that moment.

“People want things that aren’t contrived,” he said, pulling at his own shirt to drive the point home. “This paint came from me working. I wanted to recreate this feeling. Once something is contrived, when you can see through it, it’s ruined. There’s only so much you want to explain.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The scamming economy

https://onezero.medium.com/the-sharing-economy-was-always-a-scam-68a9b36f3e4b

The Sharing Economy Was Always a Scam

‘Sharing’ was supposed to save us. Instead, it became a Trojan horse for a precarious economic future.

Susie Cagle

Mar 7

Founded in 2014, Omni is a startup that offers users the ability to store and rent their lesser-used stuff in the San Francisco Bay Area and Portland. Backed by roughly $40 million in venture capital, Omni proclaims on its website that they “believe in experiences over things, access over ownership, and living lighter rather than being weighed down by our possessions.”

If you’re in the Bay Area, you can currently rent a copy of The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up by Marie Kondo from “Lan” for the low price of $1 per day; “charles” is renting a small framed lithograph for $10 a day; and “Tom” is renting a copy of the film Friends With Benefits (68 percent on Rotten Tomatoes) on Blu-ray for just $2 a day. Those prices don’t include delivery and return fees for the Omni trucks traversing the city, which start at $1.99each way.

In 2016, Omni’s CEO and co-founder Tom McLeod said that “lending enables Omni members to put their ‘dormant’ belongings to good use in their community.” That same year, Fortune said Omni “could create a true ‘sharing economy.’” For a while, the tenets of the sharing economy were front and center in Omni’s model: It promised to activate underutilitized assets in order to sustain a healthier world and build community trust. In 2017, McLeod said, “We want to change behavior around ownership on the planet.”

Just three years later, those promises seem second to the pursuit of profit. In 2019, the Omni pitch can be summed up by the ads emblazoned on its delivery trucks: “Rent things from your neighbors, earn money when they rent from you!”

For years, the sharing economy was pitched as an altruistic form of capitalism — an answer to consumption run amok. Why own your own car or power tools or copies of The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up if each sat idle for most of its life? The sharing economy would let strangers around the world maximize the utility of every possession to the benefit of all.

In a 2010 TED Talk, sharing economy champion and author Rachel Botsman argued that the tech-enabled sharing economy could “mimic the ties that used to happen face to face but on a scale and in a way that has never been possible before.” Botsman quoted a New York Times piece in saying, “Sharing is to ownership what the iPod is to the eight track, what solar power is to the coal mine.” In 2013, Thomas Friedman proclaimed that Airbnb’s true innovation wasn’t its platform or its distributed business model: “It’s ‘trust.’” At a 2014 conference, Uber investor Shervin Pishevar said sharing was going to bring us back to a mythical bygone era of low-impact, communal village living.

More than 10 years since the dawn of the sharing economy, these promises sound painfully out of date. Why rent a DVD from your neighbor, or own a DVD at all, when you can stream your movies online? Why use Airbnb for a single room in your home when you can sublease an entire apartment and run a lucrative off-the-books hotel operation? Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb — startups that banked on the promises of the sharing economy — are now worth tens of billions, with plans go public. (Lyft filed for an IPO on March 1.) These companies and the pundits who hyped them have all but abandoned the sharing argument that gave this industry life and allowed it to skirt government regulations for years. Sharing was supposed to transform our world for the better. Instead, the only thing we’re sharing is the mess it left behind.

The first glimpses of the sharing economy emerged years before the term came into popular use. In 1995, Craigslist mainstreamed the direct donation, renting, and sale of everything from pets and furniture to apartments and homes. Starting in 2000, Zipcar let members rent cars for everyday errands and short trips with the express goal of taking more cars off the road. And CouchSurfing, launched as a nonprofit in 2004, suddenly turned every living room into a hostel. This first wave of sharing was eclectic and sometimes even profitable, but before the mass adoption of the smartphone, it failed to capture the public’s imagination.

Though its origin is vague, many credit the introduction of the term “sharing economy” into the broader tech lexicon to Lawrence Lessig, who wrote about sharing in his 2008 book Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. The Great Recession was just setting in, and the sharing economy was touted as a new DIY social safety net/business model hybrid. The contours of the term were never particularly clear.... (((etc etc)))

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Budaya Remix sangat berkembang hingga kini.

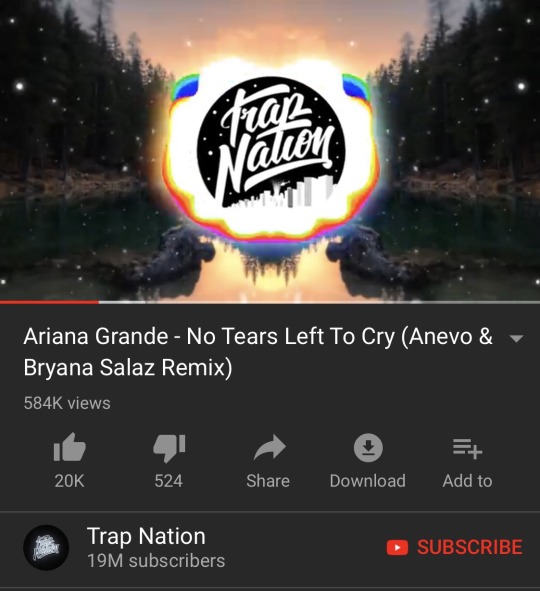

Upaya komunitas pada penciptaan konten kolaboratif merupakan fenomena khalayak yang semakin luas menjadi lebih jelas dan lebih aktif dalam menciptakan dan berbagi konten mereka. Collaborative mashup as produsage sendiri dilihat sebagai sebuah tindakan partisipasi yang merupakan bagian dari pengembangan-pengembangan konten dan peningkatan konten secara berkelanjutan. Remix di dunia musik, memberikan alternatif atau variasi dari sebuah konten mainstream. Misalnya saja pada video berikut:

Pada video tersebut, menunjukkan ada pihak yang mengembangkan lagu “No Tears Left To Cry” menjadi sebuah karya yang memiliki beberapa tambahan background nada. Fenomena ini merupakan sebuah proses tanpa akhir yang memberikan alternatif dalam sebuah karya. Prinsip dari produsage itu sendiri bersifat partisipasi terbuka, namun memunculkan evaluasi dari khalayak umum. Video tersebut memiliki berbagai macam komentar terkait dengan video yang diunggah oleh akun bernama Trap Nation.

Oleh: Intan Sarah Ceasaria - 1606823613

Sumber:

Lessig, Lawrence (2008) Remix: making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy, pp.23-31

Bruns, Axel (2010) Distributed Creativity: Filesharing and Produsage

https://youtu.be/Ii1EmWk6u_w

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marketing Strategy era Produsage

Sebelumnya sebagian besar konten di produksi oleh produsen media, namun dengan berkembangnya teknologi intenet konsumen media juga dapat membuat konten yang biasanya disebut Used Generared Content atau Produsage. Dengan berbagai macam jenis konten buatan pengguna dan publikasi di berbagai macam platform secara terbuka memiliki potensi marketing yang besar. Seseorang dapat dengan mudah memproduksi konten mulai dari humor, budaya, kuliner, edukasi dan menyebarkanya di berbagai platform. Informasi mengenai produk dan jasa akan cepat menyebar, itulah mengapa konsumen lebih suka membaca review daripada iklan produk itu sendiri.

UGC di zaman Produsage ini tak hanya membatasi konsumen dalam memberikan review saja, namun konsumen juga dapat memposting konten dalam bentuk tulisan, foto dan video. Pemanfaatan UGC ini salah satunya adalah call to action, mengajak konsumen untuk membuat konten dengan penggunaan hastag dan kuis berhadiah untuk mendapatkan engagement konsumen. Selain itu, engagement konsumen di dapatkan perusahaan dengan melakukan Brand Partnership yaitu mengajak influencer media sosial yang memiliki konten relevan terhadap produk tersebut. Konten bersponsor yang dikemas secara soft-selling dan seakan-akan direkomendasikan oleh influencer lebih efektif. Influencer mampu mempromosikan produk secara otentik dan lebih personal karena pada awalnya konten yang mereka miliki lebih dulu disukai oleh konsumen. Mereka memberikan kesan bahwa sebuah produk itu bagus, dan bisa membangun kepercayaan dengan follower. Sehingga, follower bisa diyakinkan untuk memilih produk tersebut. Lawrence Lessig mengemukaan 2 budaya yaitu Read/Only (RO) dan Read/Write(RW) culture. Dalam perkembangan web 2.0 seseorang tidak hanya membaca (RO), namun mereka juga dapat mengintrepetasikan bahkan menciptakan kembali konten tersebut dengan kreatifitas sendiri (RW). Contohnya pada Video Remix oleh Eka Gustiwana” Parodi Musikal Indoeskrim”, dimana video tersebut merupakan strategi marketing Indoeskrim yang bekarja sama dengan influencer dan co-creator Eka Gustiwana untuk menarik perhatian konsumen.

youtube

Namun, dalam penerapanya konten yang dibuat untuk memasarkan produk tetap harus relevan dan target audience yang tepat. Konsumen sudah dapat mebedakan konten iklan fiktif dikarenakan informasi dapat diperoleh dari manapun sehingga konsumen juga dapat membandingkan dengan isi konten lainya yang lebih relevan.

Sumber:

Bruns, Axel (2010) Distributed Creativity: Filesharing and Produsage.

Lessig, Lawrence (2008).Remix: making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy, pp.23-31

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QTL3ge7otgs, diakses pada Sabtu 7 April 2018.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parodi = Plagiarisme Halal?

Saat ini semakin marak parodi diitemui. Parodi adalah suatu hasil karya yang digunakan untuk memelesetkan, memberikan komentar atas karya asli, judulnya ataupun tentang pengarangnya dengan cara yang lucu atau dengan bahasa satire. Saat melakukan parodi bagaimana nasib copyright dari karya asli?

Sebagai salah satu contoh parodi adalah parodi trailer Dilan 1990.

Pada dasarnya tidak ada karya yang 100% murni dari pemikiran seseorang, namun suatu ide muncul karena terinspirasi oleh karya-karya lain. Parodi dapat dilakukan, hanya saja dalam penggunaan konten asli seperti musik dan-lain-lain harus menyantumkan sumber.

Di Indonesia sendiri tidak memiliki “batasan wajar” penggunaan konten orang lain. Saat ini hanya Amerika Serikat yang memiliki perlindungan tersebut. Sebagai masyarakat yang teredukasi dengan baik, kita harus berhati-hati dalam membuat suatu konten. Walaupun hanya berniat membuat sebatas parodi yang ringan, tetapi harus tetap berhati-hati.

Referensi:

Bruns, Axel (2010) Distributed Creativity: Filesharing and Produsage

Lessig, Lawrence (2008) Remix: making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy, pp.23-31

youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dunia Berkembang (4)

Menurut Lawson, refleksi budaya pada abad ke-20, mencerminkan kekhawatiran Sousa yang terwujud dengan kemunculan infernal machines yang dapat merekam dan membuat performa musik diabadikan dalam bentuk benda berwujud tangible, dapat diduplikasi, dan dijual melalui industri rekaman yang semakin marak. Salah satunya melalui Ponograph, kemudian berkembang menjadi lebih virtual dengan penyiaran musik-musik melalui broadcast radio, hingga terciptanya bentuk terbaru dalam broadcast television. Lawson menyatakan bahwa hal tersebut merupakan perwujudan persaingan antara teknologi budaya RO (Read/Only). Setiap siklus menghasilkan pembaharuan teknologi yang lebih baik. Hingga pada abad ke-21, budaya RO justru terus menghasilkan industri yang sangat bernilai bagi perkembangan ekonomi Amerika. Budaya RO telah membuka jutaan lapangan pekerjaan dan mendorong terbentuknya ‘popular culture’.

Kelompok 12 (Intan Khasanah - 1406556261)

Sumber Referensi:

Lessig, Lawrence. (2008). Remix: making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy, pp. 23-31. United States: The Penguin Press.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Kreasi Shia LaBeouf di Era Konvergensi

JUST DO IT!

sumber: https://youtu.be/ZXsQAXx_ao0

Sebagian orang mungkin saat mendengar kata ini, teringat dengan salah satu brand sepatu. Namun, Just do it yag satu ini berbeda. Just Do it yang satu ini adalah karya miliki Shia LeBeouf, seorang aktor asal Amerika yangs sering melakukan tindakan “unik” di bidang karya seni. Dari memainkan beberapa film, hingga menonton film sendiri karyannya, hingga membuat karya video dengan latar belakang green screen. Semua tindakan yang dia lakukan bertujuan untuk mengharga karya seninya sekaligus meningkatkan engagement dengan penggemarnya.

Dalam tulisan ini akan dibahas salah satu karyanya yang berjudul Just Do It!. jadi karya ini adalah video tentang kutipan motivasionalnya dia dengan latar belakang green screen. Lalu setelah diunggahnya video ini, langsung banyak video video lain yang “mengutip” adegan dari Just Do It ke dalam Videonya. Dari sesederhana, video abstrak kumpuan just doit setiap 3 detik, sampai dengan parodi film film aksi yang selipkan gambar Shia Lebeouf sambil berterika Just Do It!

Sumber: https://youtu.be/C59UW63t3HI

Seperti yang sudah diketahui pada pembahasa pembahasan sebelumya mengenai sifat konvergensi, yaitu tidak adanya batasan geografis dan menjadi global vilage, orang indonesia pun ikut partisipasi dalam membuat parodi video ini, salah satunnya yaitu Fluxcup. Fluxcup membuat video dengan gambar asli shia lebeouf, namun di dubbing dengan Bahasa Indonesia yang sebarnnya tidak nyambung kalimat kalimatnya. Hal ini menujukan bagaimana budaya partisipasi di era konvergensi, memunculkan fenomena remix

Rujukan

Bruns, Axel (2010) Distributed Creativity: Filesharing and Produsage

Lessig, Lawrence (2008).Remix: making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy, pp.23-31

1 note

·

View note

Text

The People’s Platform: A critique

Taylor states in multiple ways that the patents and copyright laws need to be reformed so that they aid in creation as oppose to hinder it. In order to accomplish these tasks, “would [essentially] mean destroying the village in order to save it” (Taylor, 222). The concept of destruction and creation go hand in hand in almost every aspect of life so why not within the field of technology. Taylor would argue that this idea of destruction for the greater good is important due to the dyadic tensions that creatives currently face. Typically, creatives have to choose between creating for personal reasons or creating simply for financial gains. The financial gains aspect is most notable because as it became more and more prominent, ideas that supported the concept of art as a free commodity eventually became intertwined with the negative aspects which embodied the societal archetype referred to as “the starving artist”. “The starving artist” archetype is a causal factor that in part stems from the mindset that value is simply the price...something can command on an open market, and if something is free than it is simply not valuable” (222). This mindset also mirrors a concept called the “paradox of value” in that art and culture are “vital...to human” existence and an abundance of it can reduce the value of an item on the open market (126). Taylor believes that through “the privatization of the cultural realm” the world is poorer seeing that the world can only be “richer when art and ideas spread” (127). Taylor's mindest contrasts the privatization of art mentality in that she has “a perspective to which...the value of art and culture [are] intrinsic, transcending the material and economic altogether; price is irrelevant” (Taylor, 222). Taylor is not alone in this type of thinking. He mention of pirate parties are an example of free culture idealists within politics.

Another idea that I found interesting was when Taylor mentioned that “private ownership that limits access to ideas and information thwarts creativity and innovation” (224). She notes that the privatization impacts the innovative capabilities of the creative commons and goes on to state that corporations should place content into the commons because it will allow them to “discover new pools of creativity inside and outside of the organization” (224). The aforestated outcome is better than the path “the average copyright infringement lawsuit [takes]...it is more affordable for the accused to settle out of court, even when their projects are likely permissible” (223). This statement is supported by other authors such as Lessig, Jenkins, Ford, and Green who would all agree that there is value in remixed media so much that spurs the same if not more engagement than content created for the sole purpose of going viral. Major corporations stop their content from spreading throughout society by overly enforcing copyright infringement cases. Within an era in which a society's primary form of communication involves utilizing a piece of technology requires companies and governments alike to take a look at the laws that govern innovation in an effort to see how citizens are negatively affected when copyright laws are abused.

Jenkins, H., Ford, S. & Green, J. (2013). Spreadable media. New York: New York University Press.

Lessig, L. (2009). Remix: Making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy. New York: Penguin

Taylor, A. (2014). The People’s Platform: Taking back power and culture in the digital age. New York: Metropolitan.

0 notes

Text

Garage Band sebagai Salah Satu Wadah Remix

Seperti yang kita ketahui, salah satu perkembangan teknologi yang sangat berpengaruh pada kehidupan manusia adalah munculnya internet. Dimana dengan keberadaan internet, apa yang dinamakan dengan budaya Read & Write semakin kental. Read & Write Culture itu sendiri adalah saat dimana masyarakat tidak hanya sekedar mengonsumsi konten-konten yang ada pada media, melainkan melakukan pembuatan ulang atau reproduksi dari konten-konten tersebut akibat adanya rasa tidak puas mereka.

Gambar diatas merupakan salah satu contoh aplikasi yang dapat digunakan untuk melakukan remix atau mashup lagu yang dinamakan Garage Band yang ada pada Mac. Tersedianya wadah ini yang bisa didapatkan secara cuma-cuma menandakan bahwa saat ini setiap orang (terutama pengguna Mac) dapat melakukan pengkreasian ulang konten-konten atau lagu-lagu yang sudah ada sebelumnya kapan saja dan dimana saja sesuai dengan yang mereka inginkan. Banyak kreasi-kreasi mereka yang kemudian di share melalui platform-platform sosial media (internet) yang dapat diakses oleh siapa saja seperti contohnya Soundcloud. Tidak menutup kemungkinan apabila pengkreasian ulang yang telah dishare tersebut kemudian dikreasikan kembali oleh orang lain sehingga hal ini menandakan bahwa budaya ini sebagai proses yang unfinished atau sesuatu yang terus berlanjut dan tidak pernah selesai. Namun di lain sisi, fenomena ini dapat membawa permasalahan yang menyangkut masalah copyright.

- Dayintani Kirana (1506756431) -

Sumber:

Lessig, Lawrence (2008) Remix: making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy, pp.23-31

google.com (gambar)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Worlds Collide in Remix Culture #1: Unexpected Musicals

Here are two of my favorite things combined: Top 40 music meets Disney musical.

youtube

youtube

The best examples of this kind of creative work (mash-up/remix) are often marked by a reframing of the original narrative, and so produce a fresh perspective on both the source material and the context in which it first existed.

Waktu mendengar lagu-lagu legendaris dari Britney Spears dan hits dari Justin Bieber, tak pernah terpikirkan ternyata lagu-lagu tersebut bisa disusun untuk menceritakan jalan cerita dongeng klasik Beauty and the Beast. Tapi otak kreatif Todrick Hall dan PattyCake Productions memungkinkan hal itu terjadi.

Hal ini merupakan salah satu contoh remix culture, dengan menggabungkan elemen-elemen budaya populer ke dalam satu bentuk baru. Lebih tepatnya, apa yang dilakukan oleh mereka adalah perwujudan read-write culture, yang artinya aktif mengkonsumsi dan mengnterpretasi konten untuk menjadi inspirasi produksi konten baru di kemudian hari.

Fandom relies on remix culture

Remix culture sebenarnya mengingatkan saya kepada budaya fandom, yang seringkali melakukan praktik remix dan mashup sebagai bentuk apresiasi dan bahan obrolan antara penggemar dari cerita tertentu, baik itu film, musik, serial TV, buku, dan masih banyak lagi. So being the multifandom that I am, saya akan menunjukkan beberapa video favorit pribadi fandom dan remix cultures ini pada post berikutnya.

Referensi:

https://techcrunch.com/2015/03/22/from-artistic-to-technological-mash-up/

Lessig, Lawrence (2008) Remix: making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy, pp.23-31

#Zhafira Athifah Sandi#SPIK600003#SAP 11#Rip Mix Burns#Remix culture#Mash up#Fandom#Disney#Top 40#pop music

1 note

·

View note

Text

Copyright Laws & Lessig

“Why should it be that just when technology is

most encouraging of creativity, the law should be most restrictive?”

― Lawrence Lessig, Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy

In Lawrence Lessig’s chapter “Remix: How Creativity Is Being Strangled by the Law” in The Social Media Reader by Michael Mandiberg, he addresses the issue of copyright laws in today’s culture. He begins by telling three stories. The first tale is about the elite and the masses used to ignore each other because they spoke different languages. Back then the elite would speak latin while the masses would speak german, english, or french. The second story he tells is in 1906 when the phonograph was created which meant the transition from a a read/write culture to only read. Therefore, people could no longer participate nor create. Someone that was particularly affected by this was an american entertainer, John Philip Sousa, who expressed the issues he had found in the use of the phonogram. He believed that the phonogram would ruin creativity and the creation of music. He was especially worried about the issue of participation which he thought was no longer allowed with this new invention. The third tale is situated in the United States in 1919. At this time the country had gone to war with alcohol, consequently the prohibition era began. However, instead of protecting people from this evil, prohibition led to people finding secretive ways to do whatever they wanted. Prohibition also led to a rise in crime. Lessig also brings attention to the Roy Olmstead case. He was one of the most famous bootleggers in the USA, his case was brought up in the court where his use of wiretapping. Judging new technologies was a struggle for the judges, as they finally agreed that wiretapping did not go against the Fourth Amendment.

Lessig continues to explore the issue of morality in technology as he explains that copyright is necessary for economic purposes. However, he believes that in order to fit today’s changing society copyrights have to evolve with technology. There is an extent to copyright, the rest can be considered creation. He finds the fact that copyright laws are too broad and lack distinction a big problem for today’s society. Then, he distinguishes two uses of copyright and copying which depends on who is doing it. Amateurs do it for fun while professionals copy things to gain money. Similarly, he believes that books are not meant for copies, while content in the internet is open to it. This is due to the diverse economies ruling the internet where certain things are free and open to anyone while others require fees and charge you for their services. He then introduces remixes as a perfect way to use content that has been previously created and re utilizing it in new ways. Remix refers to the changing, removing or adding of content to something already created. Lessig uses examples of youtube videos with the same songs and concepts yet created by people in different places of the world. Moreover, the benefits and problems of remixing are exposed. Some of the positive things are how it enhances creativity as well as a sense of community. Lessig continues the chapter by explaining that there are benefits to copyright laws such as the economic features as well as the fact that it incentives people to create more. He does however think that currently people are obsessed by copyright and these laws. Lessig sees this as unproductive and connects it to the prohibition story where people react aggressively to controlling laws. He therefore believes that these laws will just bring creative underground. Lastly, he ends the chapter by asking people to contribute to creative commons and to fight for the end of this copyright war.

youtube

0 notes

Text

Nền kinh tế chia sẻ nghìn tỷ USD là một cú lừa vĩ đại?

Marketing Advisor đã viết bài trên http://cuocsongso24h.com/nen-kinh-te-chia-se-nghin-ty-usd-la-mot-cu-lua-vi-dai/

Nền kinh tế chia sẻ nghìn tỷ USD là một cú lừa vĩ đại?

Trong nhiều năm, kinh tế chia sẻ được ca ngợi là mô hình “tử tế hơn” của chủ nghĩa tư bản, là giải pháp đối phó với nạn tiêu dùng vô độ. Tại sao bạn phải sở hữu một chiếc xe hơi khi mà nó nằm lì trong gara cả tuần lễ? Kinh tế chia sẻ sẽ giúp những người xa lạ trên khắp thế giới sử dụng tài sản của mọi người vì lợi ích chung.

Năm 2009, New York Times dẫn lời tác giả Rachel Botsman khẳng định: “Chia sẻ tác động tới sở hữu giống như cách iPod tác động tới máy cassette hay điện mặt trời tới các mỏ than”. Năm 2013, cũng trên New York Times, chuyên gia Thomas Friedman – tác giả cuốn Thế giới phẳng – mô tả đột phá đích thực của Airbnb không phải là nền tảng hay mô hình phân phối, mà là “niềm tin”.

Tại một cuộc hội thảo năm 2014, nhà đầu tư Shervin Pishevar – từng đổ tiền vào Uber và Airbnb – tuyên bố hùng hồn rằng kinh tế chia sẻ sẽ đưa loài người trở lại với thời kỳ sinh sống mang tính cộng đồng cao, ảnh hưởng môi trường thấp.

Biếm họa về kinh tế chia sẻ của Dave Arcade. Ảnh: Medium.

Một số nghiên cứu cho rằng nền kinh tế chia sẻ sẽ đạt quy mô 335 tỷ USD tại Mỹ vào năm 2025. Năm 2016, chính phủ Trung Quốc thống kê kinh tế chia sẻ nước này đạt quy mô tới 500 tỷ USD.

Theo Medium, hơn 10 năm kể từ khi “bình minh” kinh tế chia sẻ, những gì xảy ra với Uber, WeWork, Lyft, Airbnb và hàng loạt startup khác ở Mỹ, Trung Quốc và nhiều nước khác cho thấy các dự đoán đầy lạc quan trước đây đều chỉ là lời hứa hão.

Thế giới mộng tưởng huy hoàng

Trên thực tế, mô hình kinh tế chia sẻ đã tồn tại nhiều năm trước khi khái niệm này trở nên phổ biến. Năm 1995, Craigslist khởi đầu làn sóng quyên góp trực tiếp, thuê địa điểm và bán mọi thứ, từ thú cưng, đồ nội thất cho đến căn hộ. Năm 2000, Zipcar cho phép các thành viên thuê xe hơi để thực hiện các chuyến đi ngắn.

Và từ năm 2004, CouchSurfing biến mọi căn phòng khách thành phòng khách sạn. Làn sóng chia sẻ đầu tiên khá hấp dẫn và một số công ty có lãi. Nhưng ở thời smartphone chưa phổ biến rộng rãi, mô hình này không thu hút sự chú ý của giới đầu tư.

Nhiều người cho rằng cụm từ “kinh tế chia sẻ” được giáo sư luật Lawrence Lessig giới thiệu với giới công nghệ trong cuốn Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy (2008). Khi đó, suy thoái toàn cầu vừa bùng lên, kinh tế chia sẻ được quảng bá là một mô hình kinh doanh mới.

Năm 2009, tạp chí online Shareable được thành lập để theo dõi phong trào kinh tế chia sẻ. Mô hình này được kỳ vọng sẽ giúp hạn chế tình trạng tiêu thụ quá mức và ảnh hưởng của nó lên môi trường. Nhà đầu tư Mary Meeker mô tả người Mỹ đang chuyển dần từ “lối sống phụ thuộc vào tài sản” sang “sự tồn tại ít phụ thuộc vào tài sản”.

Nhà nghiên cứu Harald Heinrichs cho rằng kinh tế chia sẻ “là con đường mới dẫn tới sự bền vững”. Chuyên gia Annie Leonard của Greenpeace tô vẽ kinh tế chia sẻ là sự đối lập của tiêu thụ. “Kinh tế chia sẻ sẽ giúp bảo tồn tài nguyên, tạo cơ hội cho mọi người tiếp cận những tài sản họ không thể sở hữu, và xây dựng cộng đồng”, bà quả quyết.

Giá cổ phiếu Uber sụt giảm 30% kể từ khi phát hành cổ phiếu ra công chúng lần đầu tiên hồi tháng 5. Ảnh: Getty.

Kinh tế chia sẻ còn hứa hẹn kết nối mọi người trong thời đại kỹ thuật số. Chuyên gia kinh tế chia sẻ April Rinne nói rằng chia sẻ sẽ tái tạo lại nền tảng xã hội của các cộng đồng gắn kết. “Việc tham gia vào hoạt động tiêu dùng chung sẽ làm tăng niềm tin”, bà viết trên Shareable.

Cơ hội kiếm thêm thu nhập bằng công việc bán thời gian như tài xế taxi hay thợ sửa chữa sẽ giúp giảm khoảng cách giàu nghèo toàn cầu. Năm 2013, nhà báo Van Jones của CNN nói rằng chia sẻ “sẽ đưa chúng ta tới tương lai bền vững và thịnh vượng hơn”.

Doanh nhân Adam Werbach thành lập nền tảng chia sẻ hàng hóa đã qua sử dụng Yerdle vào năm 2012. Khẩu hiệu của ông là: “Hãy ngừng mua sắm và bắt đầu chia sẻ”. “Hàng loạt công ty nhỏ cùng lao vào lĩnh vực này. Các nhà sáng lập đều chơi với nhau. Đó là một cộng đồng. Tôi từng hi vọng mô hình này sẽ chinh phục chủ nghĩa tư bản”, ông Werbach kể về thời kỳ đó.

Biểu tượng Lyft

Một biểu tượng của nền kinh tế chia sẻ và sự phát triển thần tốc của nó là ứng dụng gọi xe Lyft. Người đồng sáng lập Logan Green kể rằng ông quá ngán ngẩm tình trạng tắc nghẽn giao thông ở Los Angeles, khi trên đường đầy xe ôtô chỉ có một người bên trong. Green cho rằng khi có thêm nhiều người ngồi trong mỗi chiếc xe, đường sá sẽ trở nên thông thoáng hơn.

Năm 2012, Lyft bắt đầu cung cấp dịch vụ chở khách qua những quãng đư���ng ngắn trong các thành phố. Lyft quảng bá mô hình “chuyến xe thân thiện”, khuyến khích hành khách ngồi ghế trước để tương tác với tài xế và trả tiền boa “tùy tâm”. Lyft lập luận rằng nền tảng này chỉ kết nối tài xế với hành khách, trả tiền là chuyện không bắt buộc, do đó không phải là dịch vụ taxi.

Nhưng chỉ sau một năm, Lyft đã đặt mức tiền cước cụ thể và huy động được 83 triệu USD tiền đầu tư. Năm 2015, Lyft nhận giải kinh tế Circulars ở Davos vì “giúp giảm tắc nghẽn giao thông trên đường phố”.

Trong nửa đầu thập niên 2010, kinh tế chia sẻ bắt đầu bùng nổ thành một mô hình kinh tế trị giá hàng chục, thậm chí hàng trăm tỷ USD. Và khái niệm “chia sẻ” cũng bắt đầu có sự thay đổi. “Chia sẻ” vẫn mang nghĩa dùng chung các tài sản ít được sử dụng. Nhưng càng ngày, nó càng mang tính chất của hình thức cho thuê truyền thống.

Cũng giống như Uber, Lyft thua lỗ hàng tỷ USD. Ảnh: Getty.

Dường như tất cả mọi thứ đều bị cơn bão chia sẻ cuốn theo. Các ngân hàng đa quốc gia đổ tiền vào hàng loạt startup chia sẻ xe đạp, ứng dụng cho phép người dùng thuê vị trí đỗ xe mọc lên như nấm, các nền tảng mua bán quần áo đã qua sử dụng xuất hiện ồ ạt… Nhiều startup lên đời “kỳ lân” như Uber hay WeWork.

Năm 2013, nhà đầu tư Steve Case tuyên bố trên Washington Post: “Hãy thắt dây an toàn. Nền kinh tế chia sẻ mới chỉ bắt đầu”. Năm 2014, lãnh đạo Airbnb Douglas Atkin khẳng định: “Kinh tế chia sẻ xứng đáng thành công vì đó là sự phi tập trung hóa tài sản, quyền lực và kiểm soát”.

Chỉ là bình mới rượu cũ

Đến giữa thập niên 2010, câu thần chú “kinh tế chia sẻ” bắt đầu đánh mất sự nhiệm màu. Các nền tảng “tiêu dùng chung” dần biến thành những công ty được định giá hàng tỷ USD.

“Sự thay đổi về nhận thức bắt đầu từ năm 2016. Mọi người nhận ra rằng mô hình này thực ra chẳng có gì là mới mẻ. Nó chỉ rẻ hơn và không được quản lý chặt mà thôi”, Medium dẫn lời luật sư Veena Dubal ở San Francisco nhận định.

Trong bài viết đăng trên Medium năm 2016, doanh nhân Adam Werbach cho rằng các tập đoàn toàn cầu đã “đánh cướp” kinh tế chia sẻ. “Các nền tảng cho thuê đạt giá trị khổng lồ nhưng không phản ánh tinh thần chia sẻ”, ông viết. “Thực tế là hàng triệu người đang chia sẻ để một số ít trở thành tỷ phú”. Ông khẳng định các nền tảng này là “cho thuê” chứ không phải “chia sẻ”.

Trong một số trường hợp, kinh tế chia sẻ làm trầm trọng thêm những vấn đề nó được kỳ vọng sẽ giải quyết. Việc tận dụng các nguồn lực dư thừa dẫn tới tình trạng tiêu thụ nguồn lực quá mức. Một số nghiên cứu cho thấy dịch vụ giá rẻ của Uber và Lyft khiến tắc nghẽn giao thông ở nhiều thành phố Mỹ trở nên trầm trọng hơn.

Đáng lo ngại hơn, chúng lôi kéo hành khách rời khỏi hình thức chia sẻ thực sự: phương tiện giao thông công cộng. Các dịch vụ gọi xe như Uber và Lyft lôi kéo nhiều người vay tiền ngân hàng mua xe trong khi không đủ khả năng trả nợ, hoặc thuê xe từ chính các công ty này.

Từng có khách chết trong căn hộ thuê của Airbnb, nhưng nền tảng này không chịu trách nhiệm. Ảnh: Financial Times.

Trong khi đó, các ứng dụng cho thuê phòng khách sạn như Airbnb thổi bùng cơn lũ đầu cơ bất động sản ở nhiều thành phố. Hàng loạt căn nhà, tòa chung cư trở thành khách sạn, khiến nguồn cung nhà đất tại nhiều thành phố đắt đỏ càng trở nên khan hiếm. Theo Medium, điều đó có nghĩa là tài sản, quyền lực và sự kiểm soát không hề được phi tập trung hóa, mà ngày càng tập trung vào các nền tảng lớn.

Hơn nữa, kinh tế chia sẻ không hề tạo ra được sự tin cậy. Thông thường, chính phủ đóng vai trò trung gian quản lý mối quan hệ giữa các công ty với người tiêu dùng. Trong khi đó, các nền tảng thường né tránh trách nhiệm khi có vấn đề xảy ra. Ví dụ, từng có trường hợp khách chết hay bị tấn công khi sử dụng dịch vụ thuê phòng Airbnb, nhưng công ty này không chịu trách nhiệm.

Các công cụ quản lý trên mạng xã hội không thể ngăn chặn được những vấn đề chắc chắn sẽ xảy ra (như khi một người xa lạ vào nhà một người khác nhờ ứng dụng Airbnb, còn khách sạn thì có những quy chuẩn an ninh nhất định). Và các công ty chia sẻ không kiểm tra chặt chẽ lực lượng freelance, nhà hay xe cho thuê.

Kinh tế chia sẻ cũng không đem lại sự ổn định tài chính. Người lao động làm việc trong các ngành kinh tế chia sẻ như tài xế Uber hay Grab đều có thu nhập thấp, không có bảo hiểm xã hội hay y tế.

Kinh tế chia sẻ đang chết

Kể từ năm 2016, các doanh nhân công nghệ và giới đầu tư phương Tây đã hạn chế dùng từ “chia sẻ”. Thay vào đó, họ sử dụng những từ như “nền tảng”, “dịch vụ theo yêu cầu” và gần đây nhất là “kinh tế gig” (nền kinh tế của những công việc tạm thời, ngắn hạn). Một số tổ chức và cá nhân từng nhiệt liệt ủng hộ kinh tế chia sẻ cũng không còn nói nhiều về nó nữa, ví dụ như tổ chức phi lợi nhuận Peers.

Năm 2018, chuyên gia kinh tế chia sẻ April Rinne – thành viên Ủy ban Kinh tế Chia sẻ Trung Quốc – thừa nhận “mặt tối” của mô hình này. Chuyên gia Rachel Botsman – người từng khẳng định chia sẻ sẽ giúp con người tin cậy nhau hơn – giờ chỉ trích công nghệ và sự tích tụ quyền lực của các nền tảng lớn “làm xói mòn lòng tin”.

Biếm họa kinh tế chia sẻ bắt đầu chết từ năm 2016. Ảnh: Medium.

Các nền tảng “chia sẻ cộng đồng” từng được chuyên gia Botsman kỳ vọng như Crowd Rent, ThingLoop, SnapGoods hay Josephine đều đã chết. CouchSurfing biến thành dịch vụ trả tiền. Theo Medium, các tập đoàn và chuyên gia không còn dùng từ “chia sẻ” nữa bởi người tiêu dùng không còn tin tưởng vào mô hình này nữa.

Doanh nhân Adam Werbach phân tích trên thực tế người tiêu dùng có chia sẻ, nhưng mô hình kinh tế này đem lại quá ít lợi nhuận. Để kiếm ra tiền, đặc biệt là lượng tiền mà giới đầu tư công nghệ mong muốn, các startup không thể chỉ tận dụng các tài sản ít được sử dụng. Họ phải có thêm nguồn lực.

Kinh doanh vì lợi nhuận đòi hỏi tăng trưởng và các nền tảng đòi hỏi quy mô. Hóa ra là chủ nghĩa tư bản không hề bị chinh phục mà nó càng bùng nổ. “Giờ tất cả chỉ là những giao dịch. Chẳng cần phải dùng những từ ngữ mĩ miều như ‘chia sẻ’ hay ‘thay đổi thế giới’ để nói về chúng”, doanh nhân Werbach cay đắng nói.

Và giờ khi kinh tế chia sẻ đã lỗi mốt, các nhà đầu tư và chuyên gia bắt đầu nói về những mô hình mới. “Hot” nhất hiện nay chính là công nghệ blockchain. “Giờ hầu như không ai biết blockchain là gì, nhưng 10 năm tới nó sẽ quen thuộc giống như Internet. Cả xã hội sẽ không thể thiếu nó”, chuyên gia Rachel Botsman viết trên Wired.

Vẫn là những tuyên bố hùng hồn, vẫn là những lời có cánh. Và rất quen thuộc.

0 notes

Text

Theme Song EURO 2016: Siapa mau buat lagu bareng David Guetta?

Menjelang diselenggarakannya pentas sepakbola terbesar di Benua Eropa, Euro 2016, David Guetta berkesempatan menjadi pembuat lagu tema dari acara tersebut. Namun, yang spesialnya adalah David Guetta tidak membuat lagu tersebut sendiri. Melainkan ia membuat lagu tersebut bersama ratusan bahakn ribuan peserta yang ikut serta dalam membuat lagu tema Euro 2016.

Seperti pada iklan diatas, para peserta diajak untuk ikut mengirimkan rekaman suaranya yang nantinya orang-orang terpilih akan digunakan suaranya untuk digabungkan oleh David Guetta menjadi sebuah mahakarya lagu tema EURO 2016. Menarik bukan?

Dapat berkesempatan menjadi bagian dari proyek yang dikomandoi oleh salahs satu DJ termahsyur di dunia. Jika dianalisa lebih jauh, ini merupakan strategi brilian yang telah direncanakan dengan baik oleh pihak panitia penyelenggara EURO. Para audiens diajak untuk ikut berpartisipasi secara langsung. Jenkins mengatakan bahwa para user jaman sekarang memiliki kecenderungan tidak hanya untuk mengonsumsi sebuah konten, lebih jauh lagi, mereka akan jadi sangat tertarik terhadap suatu konten atau produk jika mereka bisa ikut melakukan partisipasi. Pada proyek ini, audiens diajak untuk ikut engage.

Jadi, disini EURO 2016 memanfaatkan budaya masyarakat era convergence yang, sebagai audiens, mereka sangat aktif terutama dalam ikut berpartisipasi dalam pembuatan konten. David Guetta yang diakhir tinggal menyelesaikan proyek dengan meng-compose semua produk yang telah dikirim para audiens menjadi sebuah kesatuan dalam bentuk lagu tema EURO 2016. Nantinya, para audiens juga akan merasa bangga karena ia bisa menjadi ‘bagian’ dari sala satu event terbesar di daratan Eropa.

Referensi:

Lessig, Lawrence (2008) Remix: making art and commerce thrive in hybrid economy, pp. 21-23

http://www.goal.com/en/news/7135/old-euro-2016/2015/12/12/18180792/sing-on-the-official-uefa-euro-2016-song-with-david-guetta

1 note

·

View note

Text

A capella Mashups & Produsage

A capella mashup sempat menjadi booming, terutama setelah penayangan film Anna Kendrick yang mengangkat tema serupa: Pitch Perfect. Akapela sendiri didenifisikan sebagai sebuah paduan suara yang sama sekali tidak menggunakan musik, suara-suara seperti iringan lagu diciptakan sepenuhnya menggunakan mulut.

Dalam perkembangannya, akapela dilakukan dengan menggabungkan beberapa lagu populer hingga menjadi sebuah harmoni yang utuh. Kita bisa melihat banyak kelompok-kelompok akapela yang mengunggah video mereka di Youtube, beberapa bahkan berhasil mengembangkan platform penampilannya hingga ke televisi dan bahkan konser dunia.

Pentatonix merupakan salah satu contoh dari kelompok akapela yang telah berhasil. Dengan melakukan mash-up pada lagu-lagu populer dengan gayanya sendiri, Pentatonix telah menjadi salah satu grup acapella yang namanya mendunia. Yang pada awalnya hanya diunggah di Youtube, kini Pentatonix bisa memiliki album mereka sendiri dan bahkan melakukan tur dunia.

Hal ini merupakan salah satu keuntungan dari perkembangan produsage yang diistilahkan oleh Axel Burns. Konsumen tidak lagi pasif menerima tayangan dan informasi dari produsen, tetapi juga turut aktif dalam menciptakan karyanya sendiri. Sama seperti pendiri Pentatonix pada awalnya, Kirstie, Mitch, dan Scotch Hoying yang awalnya ditolak dalam audisi justru mendapat banyak perhatian ketika mengunggah karyanya di Youtube.

Perkembangan teknologi telah memudahkan kita dalam berkarya, alangkah baiknya sebagai pengguna media saat ini kita dapat memanfaatkan fasilitas tersebut sebaik-baiknya untuk terus menciptakan karya.

SUMBER:

Bruns, Axel (2010) Distributed Creativity: Filesharing and Produsage

Lessig, Lawrence (2008) Remix: making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy, pp.23-31

http://www.casa.org/content/exclusive-interview-pentatonixs-scott-hoying

sumber gambar: https://www.grammy.com/grammys/artists/pentatonix

3 notes

·

View notes