#xdga

Photo

Offenbach am Main, Germany

Universtiy of Design

Competition 1st Prize

https://www.topotek1.de/buildings/hochschule-fuer-gestaltung/

https://xdga.be/project/hfg-school-of-arts

Topotek1 / Xaveer de Geyter Architects

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

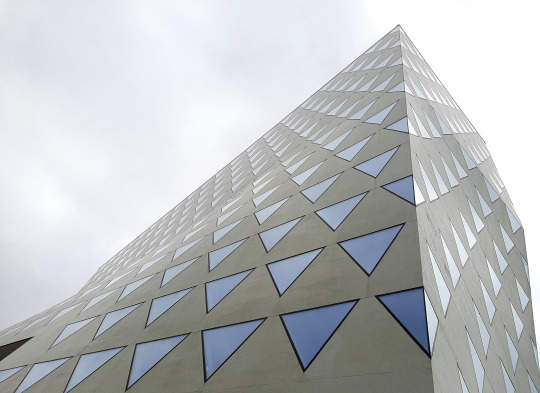

"Headquarters of the Province of Antwerp", Antwerp, Belgium [2019] _ Architects: XDGA | Xaveer De Geyter Architects _ Photos by Spyros Kaprinis [08.05.2023].

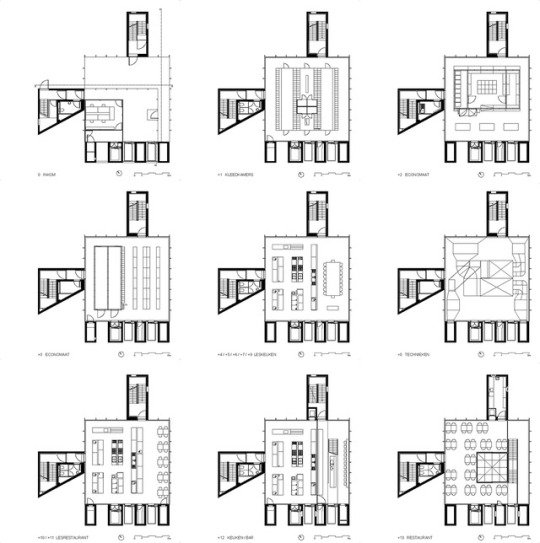

"The new building replaces a complex of modernist building volumes that used to occupy the entire site and that could not be adapted to today’s sustainability standards. As the Antwerp city centre has few public green surfaces, the transformation of the site from a merely private, mineral and infrastructural area into a public garden is a crucial requirement of the competition brief. Surrounded by fragments of public green, the parcel is key to the formation of a larger, coherent park. Another – contradictory - demand was to maintain a more recent representational pavilion, which was positioned as an obstacle in between the fragments.

By situating the full program in a compact volume across the pavilion, this frontage is cut up and the main entrance is brought close to the street. This large volume, however, divides the park in a front and a back garden. Finally, by rotating the plan around one of its corners as it climbs up, the building shifts towards the centre; existing neighbouring buildings are respected and a sculptural form emerges. During the design process the pavilion building is at last replaced by a glazed volume to house the congress and exhibition part of the programme. The building is conceived as a bridge structure over and across the pavilion.

At the centre of the plan one large steel truss spans from one core to the other. Two more trusses are integrated in the concrete side walls and their triangulation defines the form of the window openings. In a next step this window form is applied all over the building as it turns out to be very efficient when it comes to an ideal balance between daylight access and overheating by the sun. The opaque façade is clad in circular, white glass mosaic while the pavilion is a fully transparent box in the park."

https://xdga.be/project/province-headquarters

#Headquarters of the Province of Antwerp#Antwerp#Belgium#2013#2019#XDGA#Xaveer De Geyter Architects#Spyros Kaprinis#2023

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

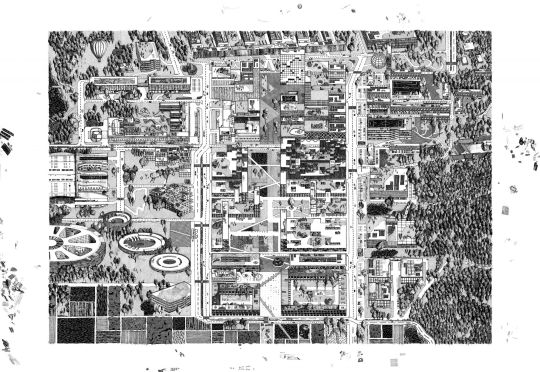

Paris Saclay // Vision du futur quartier Palaiseau à Paris Saclay

by Eva Le Roi, for Xaveer De Geyter (XDGA).

http://eva-le-roi.com/

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Precedent research: Melopee School/ XDGA, Belgium

Confined within a steel grid, all the schools functions, learning spaces and recreational spaces are all fitted within the grid. The playground has been stacked, maximising the space. What I like is the simplicity within the architecture. Whilst it has a car-park like feel, it is highly practical, simple and functions to serve this purpose- and within such a confined space.

0 notes

Photo

Escuela Melopee / XDGA - Xaveer De Geyter Architects

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Headquarters of the Province of Antwerp - XDGA

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ecole polytechnique mutation study . paris , silkscreen

xdga

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Province Headquarters, Antwerp

XDGA

2019

Mathias van Rossen

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

XDGA: Rogierplein Brussel

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Maison des Médias#XDGA#Xaveer De Geyter Architects#Brussels#Belgium#2017#competition entry#office#architecture

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

***Political animals*** A few years of work wrapped-up in fancy paper and nice essays from Sarah Whiting Philip Ursprung. Congratulations and thanks to all colleagues, present and past, for making all of these great projects! Check for more info and insights @xdga.be or @el_croquis #xdga #260projects #elcroquis #xdgaarchitects #xdga_archives #xdgarchitects (at Sint Gillis) https://www.instagram.com/p/CEUp-fNJnkX/?igshid=p7r6y09pwqt3

0 notes

Photo

Antwerp Provinciehuis is nominated for eumies award 2020

Congratulations to the team!

https://eumiesaward.com/work/4499

Photo: XDGA - Matthias Van Rossen

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An excerpt from Christophe Van Gerreway’s text on Brussels, Architecture and the City for XDGA’s 161 Publication (2013).

XDGA from A to Z

Christophe Van Gerrewey

Architecture

Architecture is holding up. Although the number of closures mainly seems to have increased since the turn of the century – and one human activity after another has come under pressure, rightly or wrongly, for being outdated and unprofitable – architecture is as necessary as ever. Architects continue to reveal possibilities, offer solutions and create opportunities. After all, despite ongoing virtualisation and globalisation, we are all bound to places, and the architect is still the best intermediary in our daily struggle with our environment, and with those who lay claim to it.

Architectural interventions do not solve problems. Instead, problems are clarified, explored in depth and analysed, often revealing in the process that the relevant issues lie elsewhere. That is precisely why a successful architectural intervention constitutes the best antidote to pessimism, conservatism or early twenty-first-century doubts. This observation is all the more remarkable when it appears that it is generally overlooked. Despite all the culture and success of architecture, the miraculous activity of the individual who makes plans (or rearranges, organises, breaks down, projects, turns around, builds or groups them together) is no more a ‘topic’ than the mystery of living human beings.

No architecture better embodies these conditions than the work of Xaveer De Geyter Architects. Each decision taken by the firm seeks to keep architecture relevant as a discipline. Thanks to architecture, something must always happen that is important and profound enough to justify the intervention of an architect. Architecture is not about imagining a nice shape for what happens naturally and that changes nothing in the course of things. The corpus of projects that De Geyter has completed since 1988 (together with a growing number of staff) is not characterised by any particular use of materials or forms. This is not just because only a limited number of designs have been executed. It is rather because this is architecture that seeks and finds its cause and reason in activities and programs, and in the people that perform them. That is precisely why it often happens that hardly anything is done. A first example is the proposal that De Geyter made in 1983 with Stéphane Beel, Willem Jan Neutelings and Arjan Karssenberg (Team Hoogpoort) for an empty but, precisely for this reason, lively Carrefour de l’Europe in Brussels. Geert Bekaert has repeatedly put forward this design as the genuine beginning of modern Belgian architecture, because it no longer came from an architect who imagines forms and presents a creation, but from an architect who organises, who offers an amnesty to reality and the built environment, and who responds to the longing for architecture not with buildings but with ideas. When XDGA again tackled the Carrefour de l’Europe in 1998, reality had changed in such a way that what was called for was no longer a void, but bulk, something the new project amply provides for. Not that attention to existing activities and their evolution necessarily blocks visible interventions – on the contrary. In other designs, underground activities and traffic flows, together with the social and urban potential of a place, are literally raised to a higher level by means of an indisputable architectural form. And one cannot deny the visible, robust, even impressive presence of many of the firm’s recent projects, although these are no more than the development of, and fitting attention to, activities and meanings.

The display and description of such an approach constitutes a special occasion – like now, in the autumn of 2013, for the first time since the retrospective exhibition at deSingel in Antwerp in 2001 and the accompanying publication, 12 Projects. XDGA has designed a spatial exhibition concept for this purpose, one that also immediately constitutes a clear overview of an architectural approach. The projects are presented in a grid composed of pedestals of varying size and height. In one of her familiar exposures of ‘modernist myths’, Rosalind Krauss described the grid as the announcement, by modern art, of ‘a will to silence, its hostility to literature, to narrative, to discourse’. Presenting architectural projects by means of a grid seems to be a way of exhibiting them in a neutral fashion without explaining what the architecture has to say. That is true to a certain extent – XDGA’s designs seldom add narrative material or content to the commissions from which they result. On the other hand, this does not mean that nothing is being told. Instead of from architecture, the stories draw their power from the subterranean and disregarded generators of the modern world and human activities.

Brussels

It is not easy to find words to describe the crucial elements in the more than 160 designs and projects that have emerged out of the XDGA approach over the past 25 years. After all, this approach is not founded on a number of clear rules or formal principles. In fact, the individual projects are based on the rules or principles drawn from a critical approach to each separate commission or situation. Just as a grid can be used to exhibit the work in an apparently neutral manner (and in such a way that many routes remain possible), so too can the putting together of an alphabet of concepts offer a solution. It is not with the 26 words of this alphabetic primer that this architecture is made, but it can, more than any other, describe, explain and interpret the work of XDGA. There is, for instance, only one architectural firm in whose alphabet ‘Brussels’ follows as naturally upon ‘architecture’ as the letter B follows the letter A in the Latin alphabet.

XDGA’s offices are in Brussels, and almost a quarter of all projects are located in this city: this is almost self-evident, precisely because in Brussels nothing is self-evident. When Roland Barthes wrote that it is the task of literature to combat the cela-va-de-soi, the societal and violent assumption of so-called truths, then the same holds for architecture, and then Brussels is the most beautiful arena imaginable. Here the organisation of the public space is particularly complicated, with so many different people, nationalities, professions, languages, policy levels, political trends and commercial convictions all having to take each other into account; with traumas, lingering problems, horrible blunders, forgotten buildings and magnificent places inter-connected like wrecks in a chain collision; and with hardly any room for architecture. That is precisely when it becomes interesting. It is only in such a context that the architect has a genuine role to play, in order, on the one hand, to respect and render legible the urban, modern and endless complexity of Brussels, and, on the other, to keep the architecture on its toes, to deliver it from pretensions, and to compel it to necessity, relevance and clarity.

In other words: Brussels is a big city, a metropolis. One of the many texts that can therefore be read in parallel with the work of XDGA is Großstadtarchitektur by the German architect and urban planner Ludwig Hilberseimer, first published in 1927 – not because all Hilberseimer’s precepts serve as a manifesto for XDGA, but because XDGA’s work can update and nuance them. Hilberseimer summarised the importance of the metropolis in the last sentence of his book: ‘the most essential qualities of the architect – his sense of mass and proportion and his organisational ability – acquire greater importance. To form great masses by suppressing rampant multiplicity according to a general law is Nietzsche’s definition of style: the general case, the law is respected and emphasised; the exception, however, is put aside, nuance is swept away, measure becomes master, chaos is forced to become form: logical, unambiguous, mathematics, law.’

With Hilberseimer’s famous drawings in mind, this position seems unrealistic. Organising the city into a logical whole following unambiguous mathematical laws would result in the elimination of its most important features: contradiction and simultaneity, or even absurdity and simply liveliness. Later in life, Hilberseimer himself criticised his early writings like Großstadtarchitektur. The obligation to give shape to urban chaos – thanks to architecture and urban planning – is not a little paradoxical. After all, what is a city if not an accumulation of chaos that offers itself in a visible form? For instance, anyone who walks down one of the city’s many axes – from the Rue de la Loi via Place Schuman to the Parc du Cinquantenaire, or from the Botanique via Place Sainctelette to the Koekelberg Basilica – will experience exactly that. And even if the urban experience or the urban landscape is not the result of a single structuring line, the views from the plateaus in front of the Palais de Justice or around the Colonne du Congrès show how form can exist with no clear structure.

Hilberseimer is not entirely mistaken – and the above examples prove it. Each case involves a situation in which the historical city – so whimsical and accidental that it could not have been designed – is framed or demarcated by a single intervention. The chaos takes shape, not because it is replaced or swept away, but because a clear intervention occurs in a limited space, in such a way that the new contrast heightens the old chaos and makes it visible, and specifies its formal characteristics.

XDGA’s Brussels projects do precisely that. Take, for instance, the design for the Rue de la Loi. The project involved the creation of an urban centre – one of many points around which the city, dependent on the city-dweller and the situation, can revolve. In the explanation accompanying the project, one reads: ‘We propose to gather the entire program into a single, highly compact urban block that will be traversed by two central axes: the Rue de la Loi and the Chaussée d’Etterbeek.’ The design was created for a competition whose goal was ‘the definition of an urban form for the Rue de la Loi and surroundings’. And indeed, this block – and its height – turns the Rue de la Loi into a visible part of Brussels. The urban richness – the combination of the presence of European legislators and civil servants (and of the primary sector) beside tourism, housing, history, trade and so forth – is highlighted permanently as its ‘existence value’. Most of the other projects for the competition, like that of the winner Christian de Portzamparc, consisted of a number of guidelines for the development of the neighbourhood. Brussels Government architect Olivier Bastin later rightly asked himself in the Belgian architectural review A+ whether ‘one needed to organise a competition at an international level to finally arrive at a decision that only continues the natural process of densification in the European district’. Whether, in other words, such a competition is able to explore the qualities of Brussels at the scale of the city, and in accordance with its character.

City

Urbanity – life in, for, of the modern city – is a condition or a climate rather than a local mood. There are countless ways to describe an urban approach to architecture, such as Roland Barthes’ abovementioned resistance to the cela-va-de-soi. In the novel The Crying of Lot 49, Thomas Pynchon gives the following description of an American city: ‘It was less an identifiable city than a grouping of concepts – census tracts, special purpose bond-issue districts, shopping nuclei, all overlaid with access roads to its own freeway.’ Based on this definition, it is the task of architecture to test the inherent validity of the concepts out of which the city emerges, and to relate them to one another as intensely as possible. This combination of analytical examinations and complex combinations is present in each XDGA project.

In a documentary devoted to XDGA’s work broadcast on the Belgian TV channel Canvas in autumn 2012, Xaveer De Geyter suggested that many of the firm’s projects ‘emerge out of an aversion to what is requested’. In a lecture given in 2009 he claimed that architecture must keep ‘a foot in the door’, and he expressed his desire to see more architecture that ‘couldn’t care less about people and about the earth’. In an article in 2001 on ‘the role of the architect in contemporary society’, published in a special issue of Hunch, the review of the Berlage Institute, De Geyter emphasised the fact that ‘architecture adds something rather superfluous to society; it questions and comments on contemporary reality and society. It has both a marginal and an essential role in the built world.’ This acceptance of the dialectical model of thesis and antithesis, of longing and its opposite, belongs to the city, and vice versa. Architecture does not resolve or establish these contradictions, but continually plays them off against one another. Everything that presents itself is taken seriously, and is simultaneously opposed, by means of analysis, criticism, reversal and questioning. ‘Freud is never far away,’ Geert Bekaert wrote in his introduction to 12 Projects – not because of some psychological interpretation or an analysis of the Oedipus complex, but because of the constant suggestion that what is seen as the truth is something else.

Modernity and urbanity, then, regardless of the whereabouts – even in suburbia, even in the sprawl, in villa districts or between farmhouses, along trunk roads and beyond roundabouts. We can turn to the houses that XDGA has built over the years in the interchangeable suburbs of Brussels, Antwerp and Ghent, where the conditions for urban living surprisingly appeared to be optimal. The most striking – and most discussed – project explores the area defined by those three cities, the so-called BAG triangle. It was carried out in 2002 at the request of deSingel and the Ministry of the Flemish Community, and it was presented in 2002 as both an exhibition and a book under the title After-Sprawl: Research on the Contemporary City.

In an interview with the newspaper De Standaard in 2001, De Geyter gave a perhaps not very glamorous but nevertheless telling description of that research process: ‘We sent out a team of Japanese researchers through Flanders equipped with cameras and note pads. They had to take photos and write down their impressions. Our intention was to investigate the urban sprawl between Brussels, Antwerp and Ghent. Because that is the reality of living. A lot of people are heaped together.’ This foreign and detached view blots out in advance any neurosis that has grown up through the historical or institutionalised approach to the problem. The fact that no local taboos can play a role – and that a fresh view sees more than a familiar gaze – is also one of the main reasons for the ‘transnational, multi-tasking model’ that Terence Riley already perceived in XDGA’s work in 2000, and the ‘potential benefits of which are just beginning to be evident.’

One of the advantages of the method used for After-Sprawl was the critical approach to the Flanders Structural Plan, in particular to the imperative of ‘dispersed bundling’ or the distinction between rural and urban areas. The core of the project consisted precisely in leaving aside that old contradiction. One of the means of doing this was to concentrate on ‘negative space’ – the large supply of undisturbed space that remains in between the buildings and infrastructure. This negative space is an experimental field for the projects which, according to After-Sprawl coordinator Lieven De Boeck’s explanation, ‘are indicated by an activity and are developed for specific locations within the Flemish Lozenge. They each illustrate an intervention that results from the tangible condition of a specific place.’ These activities – shift, overlay, insert, hide, frame, found, connect, array, add – ‘design’ the space in the BAG triangle, not by opting for densification or openness, but for a composite of the two, for a precisely defined architectural articulation of the space that already partly existed.

After-Sprawl did not go unchallenged – the discussion it generated still makes for exciting and relevant reading ten years later. It began in the publication itself, where Geert Bekaert introduced the project, notably by commenting on an e-mail exchange of views between XDGA and cultural philosopher Lieven De Cauter, who held firmly to the idea of the classical, modern, almost isolated city. The paradox, Bekaert argued, was that XDGA acknowledged this urbanity in the sprawl – both as a presence and the future – and in this way continued to emulate the city and its development, albeit without limiting the resulting urbanity to a few enclaves. This objective was rejected by Christian Welzbacher, writing in Archis: ‘how naïve can one actually be in this world … – [After- Sprawl] has nothing whatsoever to do with architecture and urban planning, and it is entirely unjust to want to think in these categories about the areas between the cities.’ In the Belgian architectural review A+ the project was labelled a ‘dead end’ by urban planner Tom Coppens, ‘an unreal discourse, in which a hip design, flashy collages and neologisms have hijacked reason’. Coppens listed all the problems that planners must take into account, and reduced the architect’s freedom of movement to virtually nothing. In the same issue of A+, Pier Vittorio Aureli (who worked on After-Sprawl) called the project a ‘trend break’: an architect who must continuously take into account the countless prescriptions and regulations of economic, bureaucratic and technocratic reality ceases to be an architect. For Aureli, XDGA concentrated, by contrast, ‘in a modest way on the architectural means available to realise a project’. In that sense After-Sprawl was not at all exceptional in relation to the firm’s work, since it presented an attempt to keep alive the dream of being able to create the world we live in, of obstinate human intervention, and of architecture as an autonomous discipline.

0 notes

Photo

Xaveer De Geyter Architects, Kitchen Tower, Brussels, Belgium, 2011

Photography Frans Parthesius

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(vía Galería de Escuela Melopee / XDGA - Xaveer De Geyter Architects - 4)

24 notes

·

View notes