Text

Irish Food History: A Companion

I haven't had much time to look at what's been done in academia around Irish Food History for a couple of years. I made some time for it this weekend, and discovered that Irish Food History: A Companion was part-published in 2023, and the first four chapters are free to download. The whole thing should be published this summer.

0 notes

Text

Iṭriya (meat dish with dried noodles)

Iṭriya is recipe 86 in the Kanz; page 130 in Nawal Nasrallah's translation, which is the version I'm using. I've cooked this a few times now; a couple of times for Dun in Mara Arts & Science Days, and once for the Travellers' Fare (Friday evening meal, as people are arriving) at Crown just gone.

I say I've cooked this: I actually change it so much it's almost certainly a different dish. But I feel the spirit survives.

Here's Nasrallah's text:

You need meat and dried noodles (iṭriya), black pepper and a bit of coriander for the meatballs (mudaqqaqa). Make meatballs with a small amount of the meat. Pound the meat with a bit of black pepper, coriander, and baked onion. [As for the rest of the meat,] boil it, strain it, and brown it [in fat]. Pound black pepper and cilantro and add them to the [fried] meat. Pour the [strained] broth on them, and when the pot comes to a boil, throw in the meatballs. [Continue cooking] until done.Add dried noodles to the pot, along with snippets of dill (ḥalqat shabath), and a small amount of soaked chickpeas. [Let the pot cook] and then simmer, and serve.

Meat, as ever for the Arabic recipes, should be mutton, and owing to the unavailability of mutton here, I use lamb. Iṭriya itself is noted in a glossary as "thin dried strings of noodles, purchased from the market and measured by cooks in handfuls". I did a bit of poking around as to what might best represent that, and while I do intend to try some Middle Eastern shops and see what they have, wholewheat spaghetti doesn't seem horribly wrong.

I've tried making the meatballs in two ways - with minced lamb, and with chopped lamb (Lady Erin's cleaver skills were employed for this at Crown). Chopped is way better, and this is not the first time I've noticed this - chopped meat and minced meat ("ground meat" for the Americans) are two very different things. A lot of Irish people seem to have the genetic trait whereby coriander tastes like soap, so I substitute parsley. And while I've tried both baked and fried onion, I didn't observe a lot of difference, so I keep using the easier fried version. I kept the black pepper, though!

A good few dishes in both al-Warraq and the Kanz use both meat and meatballs. I really like the effect, I have to say; it gives textural variation without mixing different things and thereby muddying the taste.

"Soaked chickpeas" becomes canned chickpeas, and I think they're not too different. They go very well with the lamb and the parsley. And the dill I add as written.

The overall dish is a dense, hearty thing, with the noodles/spaghetti leading, and plenty of meat in among them. It's a good dish for people arriving at an event, and it's been popular every time I've cooked it. Lady Aoife, who usually eschews carbohydrates, has been known to curse my name and reach for the tongs when it appears.

#medieval cookery#sca cookery#food history#sca#medieval arabic food#the kanz#nawal nasrallah#nasrallah#itriya#noodles

1 note

·

View note

Text

An Early Irish Feast for Drachenwald's Spring Crown, AS LVIII

Spring Crown this year was hosted by Dun in Mara in the territory of Glen Rathlin. As with almost all SCA projects, this feast didn't quite hit all the things I intended. In particular, I'd been thinking of having documentation available alongside it, and of a few more dishes that didn't make it in the end. A fermented porridge was high on that list. Next time!

Before I start talking about food, though, let me thank my kitchen crew: THL Órlaith Caomhánach, Lady Gabrielle of Dun in Mara, Noble Mallymkun Rauði, Lady Erin Volya and Cassian of Allyshia. There were a few other folk in and out of the kitchen too (THL Yda Van Boulogne did excellent work on the various flavoured butters), but these five did the bulk of the work. Lady Erin also provided lunch; cooking at Crown for 80 people as her first event cookery is notable.

The main idea here was to lean heavily on seafood, which isn't often done in SCA feasts in my experience, and represents the food of Ireland well. I also wanted to include pork as a main meat, emphasise oats and barley, and use plain vegetables presented well. There were to be condiments on the table, hence Yda's butters: plain, honey, mackerel and garlic-and-chive, as well as green sauce (largely Órlaith's work, with Cass finishing it out). Condiments and the number of them available were an important aspect of Irish medieval hospitality.

I also wanted to nod to the usual progress of early Irish feasts, which started with formal services and frequently ended up so raucous and drunken that the nobility woke up the following morning on the hall floor along with everyone else. So we served to the tables to begin, and then had a less and less orderly buffet.

The first "course" was a set of pottages. The main one was pork, cabbage, onion, carrots, turnips, and barley, which had been slowly cooked down over a number of hours. There was also a version with lamb, for those who couldn't eat pork, and this doubled as the gluten-free version, having no barley. And there was a vegetarian one, including barley, but substituting mushrooms for the meat. These were served with flatbreads, risen yeast dough having been a tough proposition in the Irish climate (and still is, really; that's why the most Irish of breads is soda bread).

As that was consumed, we stocked the buffet with: sides of salmon (steamed then baked), mussels (boiled), monkfish and mackerel (also steamed and baked), chicken pieces (baked), hard-boiled eggs, turnips with butter, carrots with honey, samphire (new to many, most enthused about it), caramelised onions, creamed leeks, buttered cabbage with and without bacon bits, and a broth-based porridge, accompanied by a variety of flatbreads and oat pancakes. And as that all cleared, we put out fruit, some cheese, some oaten biscuits, and a "cheesecake", of sorts.

Everything was plausibly pre-Norman Irish, with the exception of the oaten biscuits and the cheesecake base, which were egregiously modern - although I could argue for something very like them. Simple cooking techniques mean that those are broadly plausible as well - steaming may seem incongruous, but I'll have more to say on that again.

It all seemed to go down well. A number of people said they weren't sure about fish, and then followed with "… but that was great!", and the green sauce, the samphire and the cheesecake were particular hits. The technique of doing a wide variety of simple things usually does well, I find; even the pickiest of eaters can usually have a few things, and the adventurous can pile their plates with a wide variety.

And I had energy enough left to wander around the party hall later offering plates of fruit, cheese and biscuits, which is one of my favourite things to do.

#sca#society for creative anachronism#medieval#mediaeval#reenactment#food history#medieval food#irish food#pre-norman irish food#ireland#medievalcore#medieval cooking#drachenwald#drachenwald crown#dun in mara

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Steel-Cut Oats

What I think of as "ordinary" porridge is made with rolled oats. However, there are also steel-cut oats (aka pinhead oats, or "Irish oats"). Steel-cut oats are the groat (the oat grain without the kernel) chopped into a few small bits. I bought a pack of them in order to try them out; they almost certainly represent a more period-accurate form of oat porridge.

They have a much longer cooking time than rolled oats (which are steamed, and thereby part-cooked); 8-10 times as long. As such, they're far more likely to burn at the bottom in a moment of inattention. Ask me how I realised this, go on.

So far, I've only made this form of porridge once, and used milk as the liquid. For completeness, I'll also try water and buttermilk. I have to say I'm not as keen on this form, so far, but I suspect that some of that is that my ASD brain has settled on rolled-oats-buttermilk-and-raspberries as the "correct" porridge, and everything else hereafter is going to be wrong unless it's distinct enough to come across as a different dish.

It does resemble the US grits a lot more than rolled oats ever do, though, and I'm given to wonder if there's a rolled corn equivalent.

Thinking about the process of preparing oats to make into porridge, I'm guessing that the actual early Irish preparation is running oat berries (maybe groats) through a quern once or twice. That would, I think, result in a variety of sizes of oat pieces; some quite large and very like this modern form, and others smaller, down to what would essentially be oat flour particles, if the quern caught it just the right way. So the cooked porridge would likely be a bit less homogenous than this, but quite possibly in a pleasing way. That'll be an experiment for a future point, when I have access to some sort of grinder. Or indeed, an actual quern.

Standard (Rolled Oats) Oatmeal Porridge

Back to The Irish Porridge Project

#the porridge project#medieval food#irish medieval food#pre norman irish food#steel cut oats#irish food#flahavans

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crustarde of Flesh

Today's experiment was a pie from Peter Brears' Cooking and Dining in Medieval England which is titled "Crustarde of Flesh". It's from the Forme of Cury originally, and while I've read the original text, I really only paid attention to Brears' version on this occasion. Essentially, you cook some poultry in a lightly sweet spiced broth including some vinegar, put the poultry in your pie crust, scatter on some dried fruit, beat the reserved broth with some eggs, and pour them over the poultry. Then you close up the pie and bake it.

I haven't used this kind of pie filling before, so I wanted to see how it would go, and Dun in Mara's Arts & Sciences day gave me a captive audience.

The pie itself came out looking pretty good, and rather more solid to the touch than I was expecting. This is with shortcrust pastry bought from Lidl; my hands are much too warm for me to be a good pastrychef, and I usually resort to buying it, or having someone else make it.

The egg-and-broth mix solidified to a scrambled-egg-like stuff, and given the proportion of broth to eggs (about 600ml of broth to four eggs), I was genuinely surprised at how much it actually did go solid.

Taste reviews from the audience were good; a few people were not quite convinced by the texture. I felt myself that if I had used five eggs (or perhaps four larger eggs), I'd have gotten a smidge more solidity in, and maybe absorbed the very last of the liquid that was knocking around in the base of the pie.

I think I'll try this form of filling again with different meats. Possibly also more meat; I feel like the egg mixture should be in among the meat pieces rather than in a layer over the top. I think I could also have let the broth cool a little more before beating the eggs into it.

Overall, I was pretty pleased with it, though. Good start to the New Year's cookery!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taking on a Protégée

I have now been a Pelican for slightly over a year. Apart from the polling on who else should be elevated, pretty much everything about being a peer is a matter of tradition and local expectation - very little is set down in writing. But one of the things that most peers do (and which I feel is most of if not the whole point of peerages) is take on specific students. For Pelicans, these are conventionally called protégé(e)s.

On November 18, AS 58 (2023 CE), at Ilchomórtas Coróineád Insulae Draconis, the Principality Crown Tourney, I took on Gabrielle of Dun in Mara as a dependent. We had a ceremony between court and feast, which was well attended by noble witnesses.

The image above shows the text of her indenture, which is derived directly from my own indenture with Genevieve la flechiere. The hand is my own pseudo-calligraphic scrawl, based on the cló gaelach - it's not authentically medieval, but for a working document in English which represents the Irish persona, it'll do. This was cut in two along a jagged line in the gap in the middle, and we each have one part. The seals on it already are marked with the House of Green ivy, and we'll add some Pelican seals in due course. The ceremony also included a reading of the lineage, which stretches back several generations to Merowald Sylveaston, knighted in AS VI.

Gabrielle and myself listening gravely to Master Agnes reading the lineage.

And the actual homage bit.

Gabrielle now has the yellow belt I wore for years, and once she has settled on her own arms, she'll add those above mine, Genevieve's, and the chequey pattern that represents Brand, Genevieve's pelican. I'm still not used to wearing a different belt, so seeing her now wearing "mine" is a bit strange. I reckon it'll settle in after a bit, though.

Gabrielle has already stepped up as Chatelaine for Dun in Mara, so her career is off to a good start. I'm extremely pleased with her.

#sca#sca pelicans#order of the pelican#protegée#gabrielle#dependents#society for creative anachronism

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Smythe of Barbavilla Papers

I noted some time back that I was going to do some work on post-SCA-period Irish recipes, with an eye to working backwards from there. I finally got that started this week by seeing some documents from the Smythe of Barbavilla Papers in the National Library of Ireland. These are a collection of stuff with dates from 1621 (so barely post-period) up to 1930, but the papers I've been looking at are from the 1690s to the early 1700s.

The whole collection is listed here. I've been looking at MS 41,603, which is a bundle containing a very varied set of stuff. Deeds, devotional material, covers of letters, actual letters, poetry, musical notation, and most importantly, a whole pile of loose recipes, commonplace books, and recipe books. Honestly, I reckon it was everything in the collection that didn't belong in any other clear category. Thus far I've looked through one folder of letters, two books (one of which is definitely a recipe book, the other more varied but containing some recipes), and about half of one folder of recipes. Some of the recipes I'm finding are for food, some for medicines, some (I think) are not recipes at all, but the ~1700 equivalent of prescriptions, and some are downright alchemical.

The latter are for the most part due to "A Book of Reaseats", which is clearly attributed to "Eliz Hughes" and dated "August 03 1701". From the handwriting, I reckon Ms. Hughes was in her teens at the time of writing (working out who she was will be research for another day), and the first few formulae in the book don't dissuade me from this idea: To make a candle burn underwater & not go out, How you may put your fingers in boileing tea with out burning your self at all, To make Steel as soft as Paste, How to wright Letters secretly, To fetch oyles or grece out of cloues, How to make a glase not burn being set by ye fire, To make a blown blader skip from place to place, To make flames suddenly come out of a pot full of water, and How to bray fine gold to write with. The recipes after this are a more conventional set of preserves, cakes, and some meats.

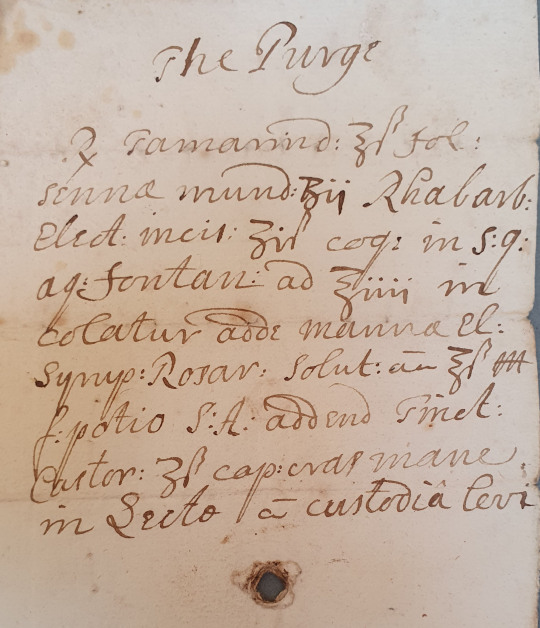

The medicinal recipes outnumber the rest, though some of those are of interest in their own right. Here's a particularly mysterious one, which seems to be in some form of shorthand Latin.

I'm not going to spend a lot of time on the non-food ones, though - someone with an interest in alchemy, herbs, or the history of medicine would have more to get from them, I feel - and concentrate on the others. The first thing I'm going to do is transcribe them, and then work up a few indexes of ingredients, methods used, and anything else that I think might point the way backward in time. I'll get back into the library in a few weeks to continue going through MS 41,603, and I have plenty to work on in the meantime.

#smythe of barbavilla papers#irish cookery#sca cooking#sca cookery#early modern cookery#irish food history#sca kitchen

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Isn't soapstone made of talc which can be a carcinogen?

Hello Anon! It would be more accurate to say that talc is made from soapstone. Talc can be a carcinogen, or at least there's a correlation between its (prolonged) use and some cancers. However, it's specifically the very fine loose dust that does that, not the stuff itself. Soapstone pots don't let that fine dust off, so they're safe to use. Indeed, even medieval soapstone carving tools wouldn't have generated dust that fine, so it's only people making soapstone products with modern grinding and sanding tools that would need to wear masks while doing so.

Separately, there are so many materials that have been demonstrated to be carcinogens - including oxygen! - that I don't think we can take minor correlations all that seriously. Crispy bacon, for instance, is far more carcinogenic than talc.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fermented Oatmeal Porridge

This is the first of the weirder-sounding porridges I tried. The idea came from Julia Skinner's Our Fermented Lives, in which she describes a number of fermented porridges, from various grains and in various cultures. One of the main ones is the Scottish sowans and the byproduct drink called swats, which are variants I'll work on in future. This one, however, is just plain oatmeal, fermented in brine.

What I did was pour some oatmeal into a bowl, add a handful of salt, pour in enough cold water to cover it, cover the bowl in cling-film, and leave it to sit by itself for six days. It developed a froth on top, with large bubbles, which formed a kind of skin on the liquid. I scooped that off, poured off the remaining water, and put the resulting gloop into a saucepan and heated it. It looked like ordinary oatmeal porridge going into the saucepan, but once it got heat on it, it thickened rapidly to the consistency of a stiff roux, and showed every sign of going completely solid and sticking to the pan if I heated it any more. So I scraped it into a bowl and tried it, first on its own, and then with a little bit of butter.

It was weird. It's not a kind of taste I'm otherwise familiar with, and it took me until I was halfway through the bowl to really pin it down. It hit a lot of the same taste notes as cheese, more so with the addition of the butter. Somewhat salty cheese, like manchego, but with more umami and sour notes. It was very smooth in texture, too; more like something you'd spread on bread.

Agnès, as the only available other person to try it on, did not like it at all. She didn't say "downright repulsive", but the thought was there. After some thought, I quite liked it; it was a very satisfying taste. I don't know that I'd eat it in the same quantities that I do plain oatmeal porridge, but I'll make it again - at the very least, so that I can try it on some other people.

LATER ADDITION, October 10 2023: I made a slightly less fermented version (5 days, not 6) and tried it on people at a Dun in Mara Arts & Sciences. Surprisingly, everyone who tried it liked it. A few people reported an initial reaction of "what did I just put in my mouth?" followed by "actually this is good". I'll be experimenting with longer ferments to see how they go.

Standard Oatmeal Porridge

Back to The Irish Porridge Project

#the porridge project#medieval food#irish medieval food#pre norman irish food#fermented food#julia skinner#fermented porridge

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Standard Oatmeal Porridge

My initial feeling was that standard oatmeal porridge didn't need much describing, so this post was here more for the sake of completeness than anything else. I've since found, as I talk to people about it and read about that there are a lot of different understandings of it, though, so I've added some detail and discussion. It's made from rolled or steel-cut oats (sometimes called pinhead oats, or for some reason, Irish oats). Steel-cut oats are the groat (the oat grain without the kernel) chopped into a few small bits; rolled oats are the groat steamed and broken with rollers instead. Broadly, In this country, Flahavan's Progress Oatlets (rolled) are probably the standard one, but even that company sells half a dozen variations - Jumbo Oat Flakes, Pinhead Oatmeal, "Super Oats", and organic variations on all of those, plus "quick" porridges, to which you just add hot water, like noodle pots. Those are essentially rolled oats that have been steamed longer, so that they're already part cooked (and have a shorter shelf life).

I typically make porridge with one part rolled oats to two parts milk, by volume, and add a little salt. It all goes in the one pot, gets stirred, and then heated (while stirring) until you have, well, porridge. It takes ten minutes on a slow stove, five to six on the induction hob. I frequently add soft fruit - fresh or frozen - or chopped apple, raisins or other dried fruit, or honey. People then add cream, jam, syrup, more honey, or lots of other things on top. Something like this, though probably a bit crunchier - with something closer to steel-cut oats, allowing for the stone querns that seem to have been Ireland's main milling technology - was probably a reasonable staple across the entire island.

Other people make porridge with water instead of milk. A variation that Noble Sarah of Dun in Mara showed me has the oatmeal added to boiling water, and then left to simmer at a low heat for a few minutes. This has the added bonus of not sticking to the pot, which honestly astonished me; I've always had to clean porridge pots with considerable elbow grease.

I've also tried it with what's sold as buttermilk here (which isn't the remnant after you make butter from cream, but instead a cultured sour milk which I suspect is related to kefir and piima), and it's pretty good too.

Broadly, people seem to either like or dislike oatmeal porridge. There's little middle ground, and I suspect that that's going to influence how people receive other porridges too.

Back to The Irish Porridge Project

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Irish Porridge Project

We know that cereal grains were in use in pre-Norman Ireland. We also know that yeast baking doesn't work very well in Ireland's climate, such that soda bread is the traditional Irish loaf, rather than the yeast breads and sourdoughs that most other European cuisines have. But bread soda wasn't available in period, so the bread of the medieval era seems mostly to have been flatbreads and some kind of biscuits or crackers, with yeast bread only really available to the rich and in (some) monasteries. Everyone else seems to have gotten along with porridges as the main use for grain. There's even mention of wheat porridges being the appropriate food for royal fosterlings.

"Porridge" in modern English mostly means that it's made from oatmeal, and indeed, it's called just "oatmeal" in some places. But it's possible to make porridge from any grain. The Southern US dish called grits is a maize porridge, for one example. So what I want to do over the next while is try out every kind of porridge that pre-Norman Irish people could have gotten hold of.

There is the issue that we don't actually know what all the grains were. We have a list from the 8th century Bretha Déin Chécht: bread-wheat, rye, spelt-wheat, two-row barley, emmer wheat, six-row barley, and oats, but we don't really know what some of those are, and the translations are dubious in some cases. In this case, I'm going to go for emmer, einkorn, durum, barley, rye and oats. That list may be adjusted if I find more or that some (durum, perhaps) were not available in period. I'll also look at grain-like stuffs like pendulous sedge and fat hen, and see what can be done with those.

Next, there are multiple forms of grain that can make porridge. The full grain "berry", the slightly trimmed groat, various crushed and rolled forms, and coarse and fine flours. In addition, there are malted, roasted, and fermented options for each, and different grains might be mixed. This is adding up to a lot of different porridges!

As I try them, I'll add links here and describe what results I get, including other people's opinions of them, when I get those. I have a couple of co-conspirators on this project, and as they send me the results of their trials, I'll add them here too.

I'd also like to credit Magister Galefridus Peregrinus, whose class in non-baking use of Fertile Crescent grains at Pennsic 50 jumped my initial research and thinking on this particular project by years.

Standard (Rolled) Oatmeal Porridge

Steel-cut Oat Porridge

Fermented Oatmeal Porridge

#irish food#medieval cooking#medieval food#sca#irish medieval food#the porridge project#medieval grains

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cooking in Stoneware Pots

For my elevation, Órlaith and Gytha got me a stoneware cooking pot. This is a pot made of actual stone - soapstone - and of a kind widely used in the Middle East in the era in which al-Warraq was writing. I have finally gotten a chance to try it out, since Pen & Sword provided me with an event where I had room on the fire and wasn't under any pressure to produce food (I was cooking a couple of Arabic stews, but they're things I know well).

The most immediate thing, which is completely obvious once it's pointed out, but which I didn't know before, is that a thick stone pot (the walls are not quite an inch thick) retains far more heat than a cast iron pot, which retains a good bit more heat itself than a stainless steel one. Nonetheless, if you take a cast iron pot off the heat, it will stop boiling in seconds. The stoneware one just keeps on boiling, and will do so for a good 2-3 minutes.

This makes sense of a number of instructions in period texts where pots are removed from the heat, and also makes sense in the context of serving the food in the cooking pot - the food will stay hot for much longer than it could in any serving dish. There's usually an instruction to wipe down the pot to remove soot and so on, so there's no doubt that it's the actual cooking pot.

Second, and this will need more trials, the food tasted different - the sweetness of the onions was far more evident. Also, there's a separation that happens when the stew is ready; you can see oil and other liquids apart from each other at the edges of the pot. This happened sooner, by far, in the stone pot. That might be because it's smaller, of course. Further experimentation needed.

#sca#medieval food#medieval cookery#medieval cooking#medieval arabic food#al warraq#soapstone#stoneware#more research necessary

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vinegar Pickling in Medieval Europe

For the last several years, I have had a research issue. Provoked by some of the discussion in this post on /r/AskHistorians (I am gothwalk in those comments), I went looking for evidence of vinegar pickling in Medieval Europe. I did not find it. There is brining and fermentation in plenty, but I was completely, completely, unable to find evidence of vinegar pickling before 1600. I have spent cumulative weeks on this.

There're even two books about the history of pickles; Pickled, Potted and Canned by Sue Shepherd and Pickles: A Global History by Jan Davison, both of which sort of shuffle gently around the issue (or possibly they just didn't think it was an issue, not being quite as obsessed with reonstructive cuisines as I am).

However, I have finally found evidence, and it's even written. It turns out there are multiple mentions of it (including making it clear it's vinegar, not just something else translated as pickling) in the Tacuinum Sanitatis, a medical treatise translated from an Arabic original (Taqwīm aṣ‑Ṣiḥḥa, by Abū 'l-Ḥasan al-Muḫtār Yuwānnīs ibn al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAbdūn ibn Saʿdūn ibn Buṭlān) to Latin (by several different translators, mostly in Italy) in the mid-13th century. There's a modern-ish English edition published in 1985 (with reproductions of period illustrations) called The Four Seasons of the House of Cerruti, by Judith Spencer. I discovered this in a reference in Julia Skinner's Our Fermented Lives, which is also an excellent book.

I am extremely pleased with this.

#sca cookery#medieval cookery#medieval pickles#pickles#pickling#european cookery#tacuinum sanitatis#research#huzzah#medieval cooking#medieval food

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

you mentioned you have a theory about british cheese, and i have to say, i'm deeply curious.

It's not a particularly complex theory. In essence: through the later medieval era and into the early modern in Britain, cheese was not a favoured food. It was what you ate with food, or when there was nothing else to eat (and this attitude is reflected in US foodways today; those attitudes came across with English people of the time). Whereas in other areas of Europe, and in Ireland in particular, cheese was regarded as very definitely food. In Irish history, there's a term best translated as "white-meats" which refers to dairy products in general; they were valued at least as much if not more than meat itself.

It takes time to work out how your local cheese works, and it's intensely variable, the more so in the absence of sterile or easily seal containers. Cheese made a few kilometres down the river, or in the next valley over, can be very different indeed because the local microbiological culture is very varied. The necessary microbiomes for some cheeses take hundreds of years to really develop.

And Britain has had successive waves of invasions which, as distinct from other places (particularly Ireland) where only the rulers were replaced, involved new populations arriving. Not so much the Romans, but the Anglo-Saxons and all their ilk, and then the Normans. In each of these waves, local cheesemaking knowledge was probably lost, and the new people had to start over with cheese that was not from local knowledge in their new place, nor from local knowledge in the place they came from - because that didn't apply any more.

Meantime, Ireland had changes of rulership every so often, but mostly the farming - and cheese-making - populations just stayed where they were, using dairy as they had for centuries, and by the time the Vikings and then the Normans arrived, probably millenia.

So British cheese was just not great, and Irish cheese, we assume, was fantastic stuff. Right up, perhaps, to the ealy 20th century, when modernisation, scientificism, and a huge focus in dairy on butter for export almost killed off the Irish cheese industry. We're starting to fix that, but there's really only about 50 years of farm-level varied cheesemaking in Ireland as yet. Given that some of that cheese is superb, I'm looking forward to what starts to be produced in the next few decades.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Féile na nÚll Menu & Analysis

I had really meant to publish the menu before the event, but ingredient acquisition took more time and effort than expected. In particular, chestnut flour, which I wanted as a thickener for various gluten-free dishes, just could not be found anywhere I tried. I didn't find that out with enough lead time to order it online. Almond flour substituted, and was fine.

Anyway. Here's the full menu, which fed varying numbers of people, but I think about 45 for the feast.

Travellers' Fare (Friday evening): Beef stew with bread and butter (vegan stew on the side, plant butter available, GF bread available).

Saturday Breakfast was produced by the inimitable Lady Meadhbh Rois inghean Uí Chaoimh.

Saturday Lunch: Chicken soup (vegan soup alongside), bread, fruit.

Feast: Roast pork (vegan nut roast on side), Frumenty (rice on side), apple sauce, green sauce, meat pies (mushroom pie on side), creamed leeks (with fake cream), buttered turnips (with plant butter), roasted onions, purple carrots (with plant butter), olives, anchovies, apple pies, blackberry and apple pies (all pies with GF/vegan versions as well, where possible).

Sunday breakfast: Porridge with cream and fruit, stewed apples, boiled eggs, cold ham, and various leftovers, mostly fruit pies.

The emphasis here wasn't on any particular production of period dishes, but on making sure everyone got good solid food. It's also an entirely plausible English Tudor menu, including the frumenty and green sauce as dishes that didn't make it through the Early Modern. As far as I can make out, everyone enjoyed it (although nobody ever tells the cook they didn't). The coeliac and vegan/vegetarian folk expressed particular approval, which was important. Anything I could make GF and vegan was made so (plant butter and almond flour are the two main tricks here).

Gabrielle and Katie were in the kitchen every hour I was, and possibly a few more, and a great deal of credit for the weekend's food being on the tables on time is due to them. Katie also set in, with very limited prior experience, to making pastry for the non-gluten-free pies, and produced some of the best I've ever encountered. She's been designated Head Pastrychef in Perpetuity as a consequence. There were also many other kitchen helpers, who've been thanked appropriately on Facebook. The relevant note here is that we had 4-5 people in the kitchen at most times, which was more than enough, and kept everyone relaxed. The SCA Kitchen playlist (85% mine, 15% Gabrielle's) was also helpful.

So. The first thing that I want to improve is the gluten-free pastry. Making it vegan as well was trivial; replace the lard/dripping with plant butter, and it's absolutely fine. Any fat will do for that, it seems, although since the traditional use for the pastry is the raised pork pie, the meat fats help match the taste. The gluten-free flour, however, could only be persuaded to make a paste, not a pastry - trying to roll it out into sheets simply didn't work. It would take the form of a sheet, alright, but if I went to pick it up, it just broke. An experimental version that Gabrielle and I did before the event could be sort-of lifted into place on baking parchment, but it broke over the contents of the pie. In theory, with a very dense, relatively smooth pie filling (such as a meat pie that's been well-packed), you could get a coherent crust, but I don't know what would happen to that as the contents shrink in baking. Xanthan gum appeared to make zero difference.

So we've some more experimentation to do there. One suggestion is to use an egg or two, which will take it away from being vegan - but a vegan pastry, using plant butter instead, should not be a problem to produce as an ordinary cold pastry. Various things will be trialled.

The green sauce came out particularly well. Órlaith did her usual superlative job of chopping herbs, primarily sorrel and mint, with some basil and thyme, some black pepper, and garlic salt. The liquid base was about 2 parts olive oil to one part white wine vinegar. We only made a small amount, but nearly all of it was eaten. Green sauce is basically a table condiment for the latter end of the SCA period in Western Europe, and I have vague plans to make and bottle some at some stage, to see how it keeps and matures in the longer term.

I made far too much of the frumenty. Bulgur wheat isn't terribly expensive, so I don't feel too bad about it, and the carbohydrates are absolutely the area in which to over-provide. But for my future reference, about 400g of dry bulgur will provide enough for about 30 people without difficulty.

The roasted onions were surprisingly popular. I think we did 11 whole onions, and only one and a half came back to the kitchen.

The meat pies disappeared in their entirety, as far as I can tell. One was a combination of minced pork, minced lamb, and whatever vegetables were to hand; the other was filled with the remnants of Friday's beef stew. I was very pleased to be able to integrate leftovers into the feast; I am completely certain that a rolling use of leftovers in subsequent days' dishes was a standard feature of any period cookery, and we don't often get to do that over a weekend.

The purple carrots were entertaining. I can't detect any difference in taste from orange carrots, but they stain everything they touch a nice shade of purple-blue. I'll get them again if I can just for that.

Overall, I'm pleased with how things came out, and I'll do either of the Arabic or Pre-Norman Irish menus I had partially worked out for next year.

#sca#sca kitchen#féile na núll#medieval food#medieval cookery#tudor food#pies#gluten-free medieval food#vegan medieval food

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Teaching in the SCA

I went to a thing at Pennsic called a Pelican/Protegé Meet-up (or something of that ilk; I can't currently get to the Pennsic Thing to see what the actual title was), and as previously mentioned, I went to a lot of A&S classes. Those two things made me think about teaching in the SCA, and specifically the teaching that happens between a peer and a dependent. And even more specifically (maybe), Pelican teaching.

My Pelican, Dame Geneviève la flechiere, never taught me or any of my fellow dependents anything in a class-like format. She didn't give homework, and most of what we did happened through working together at events, or on projects, or just by discussing situations that were happening, and what could be done about them. That's something that still happens even though I and Sela (one of her other dependents) were elevated last year, and I expect it to keep on happening, and even though she's moved back to Ealdormere.

But there's a lot of teaching for A&S in class-like formats, and plenty of apprentices get homework. Nearly all squires do, and I assume that dependents-of-the-Order-of-Defense-who-still-don't-have-an-agreed-upon-name-or-anything* frequently do as well. And while I don't assume that my experiences as a Pelican dependent are universal, I've honestly never heard of such formal teaching in that context.

I've tried to think about how you could teach Pelican-ing, and I'm not entirely sure it's there. You can teach basic organisational skills, like how to use spreadsheets, how to work out a timetable that doesn't require any one instructor to be in two places at once, and even how to cost out the food for an event, but none of those things are going to add up to peerage-level "prowess", no matter how well they're learned. I can imagine a class in "how to delegate", but it doesn't mean the person will delegate. Gods know I'm fine with the theory, and still spring out of my chair to do the thing myself in practice. It seems like learning by example, by advice, and by discussion is pretty much the only way to get there.

In thinking about this, though, I came across a post about teaching and evaluation in a college context, and how they're two entirely different processes that don't benefit from being carried out by one person. We explicitly don't have - and shouldn't have! - strict evaluation criteria for peerages, but there's still some food for thought there in terms of how we teach and how we look at the results of teaching.

* It would be lovely if the Order of Defense would get on the name thing, and agree on a belt colour or something to mark their dependents.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A brief account of Pennsic 50

TLDR: Fantastic event, pity about the climate zone it's in.

Let me get that negative bit out of the way: I don't handle heat well, and Pennsic has absolutely punishing heat and humidity. I was basically unable to do anything useful between 13:00 and 17:30 on any given day (and right through the evening in the lower-lying lake-adjacent parts of the site). I tried to tough it out, but that didn't work, and I ended up sitting in the air-conditioned internet café for many of those hours through much of War Week. I didn't as much as see the battlefield, let alone the opening ceremonies, field battle, etc, because I would have just passed out on the field. As it was, I pretty much passed out on the day we were packing down because I was lifting and moving stuff in the heat, and couldn't go sit in the aircon. It was quite frustrating, and there was absolutely nothing that could be done about it.

So what I did do was go to classes in the mornings, do shopping at hours when I was able, and either hang out at our own camp, or go to various parties in the evenings.

The array of classes was downright incredible. There was no topic, as far as I could see, that was not touched upon at least. I went to about eight or ten in total, plus the sizable Arts & Sciences display. All of the classes I went to were food-related, and one of them, given by Magister Galefridus Peregrinus, jumped one of my longer-term projects forward by, I estimate, about two and a half years (it was about non-baking use of Fertile Crescent grains in Medieval Europe, and is relevant to my pre-Norman Irish Cooking stuff). I have good notes from many of the rest, too, and a raft of things to look up.

The shopping was also unbelievable. 200 stalls or so, and while some of them were more LARP or gamer-oriented, most were relevant. for myself, I got a basket-backpack of a kind I've been looking for for years, a pair of turnshoes, two small cast-iron pans, a new tooled leather belt, about six different kinds of smoked salt, various bits of Pelican bling, many metres of Drachenwald trim, and (appropriately) a very nice seax as a kitchen knife. Probably a lot of other stuff, too - I haven't unpacked yet - but those are the things that come to mind. I also bought a veritable pile of stuff for other people, and have taken note of a host of merchants for online buying later. There were some interesting gaps in the market, too - I would have thought that pre-strapped or bossed shields would be commonly available, and saw essentially none, and that there would be more period-ish cookware and camp equipment for sale (there was some, but not very much).

Speaking of cookware, it was notable how few camps had any period cooking arrangements. I saw some very impressive modern camp kitchen setups (the East Kingdom State Kitchen was essentially equivalent to the best indoor kitchens I've cooked in), but I saw precisely two period-ish kitchens, out of hundreds of camps (although I didn't see them all; that was just not possible). Given there were more than 11,000 people there, it was essentially not a thing that was done.

Some of the camps and buildings were terrifyingly fine, though. The Pleasure Pavilions were a set of absolutely beautiful tents, and Casa Bardicci is an actual miracle of construction. There were a varierty of other buildings, as well as gatehouses, ships, and so forth.

The social side of things is a slower burn. Putting faces to names, and meeting many of Nessa's fighting family was excellent, and there've been a number of conversations started that I think will go on for years (and a plot to try out various porridges on people with Baron Cormacc Mac Gilla Brigde). I also caught up with a number of people I haven't seen in years, and decades in some cases. I was particularly pleased to get to spend time properly with Duchess Qamar al-Nisa and Lady Alina Rose, who are two of my favourite people.

I expect I'll have some more thinking on various aspects of the event in time, and how some of the things there can be transferred to events here. I'd like to particularly note that climate aside, the site is fantastic, in terms of both geography and facilities. It also had fireflies and crickets, which made up for a lot.

17 notes

·

View notes