Video

0 notes

Photo

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Too big”

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Did you know that ‘goo’ means shit in the Hindi language?

0 notes

Text

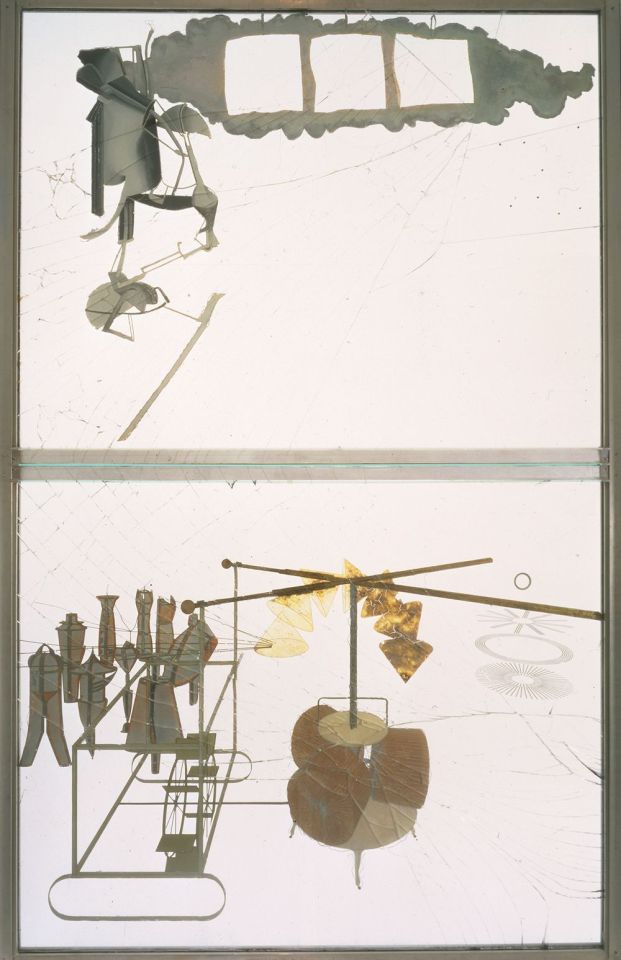

ART: An Analysis of The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (1915-1923) by Marcel Duchamp

Duchamp worked on The Large Glass from 1915 to 1923, with an exception of stay in Buenos Aires and Paris in from 1918 to 1920. He published three collections of notes during his lifetime: the “Box of 1914”, the “Green Box” (1934), and “A l’infinitif” (1966). The notes explained each component’s function and symbolic meaning. Another 289 unpublished notes were discovered after his death, at least 100 of which date to the period of his intense work during the 1910s on the Large Glass project. The “Green Box” is supposed to complement the visual experience of the viewer. Arturo Schwarz has translated excerpts from the “Green Box” in The Essential Writings of Marcel Duchamp, which has been used for the analysis of the Large Glass in this paper.

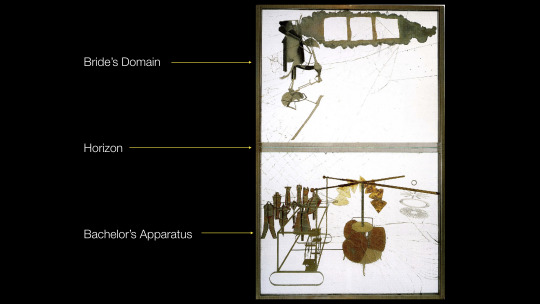

The Large Glass consists of two glass panels, suspended vertically and measuring 109.25 inches × 69.25 inches (277.5 cm × 175.9 cm). Duchamp used various challenging and unconventional materials for this piece. The glass panels are set in a metal frame with a wooden base, and used materials such as lead foil, fuse wire and dust for his “delay in glass”. It is a two-dimensional depiction of the dynamic interaction between these forces governed by a set of decided physical laws. It shows a series of interactions suspended in time, hence called a “delay in glass”.The upper glass pane is named the Bride’s Domain while the lower is named the Bachelor Apparatus. The Horizon, a wooden base in between, separates the two.

This extraordinary masterpiece is inclusive of many, if not all, works of his lifetime. For instance, The Chocolate Grinder (1914) and the Draft Piston (1914), both are directly placed as crucial components of the Large Glass, while others, namely The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes and The Nude Descending the Staircase, No.2, seem to resemble other components in the painting, as pointed by Bradley Bailey in his essay, “Passionate Pastimes: Duchamp, Chess, and the Large Glass”. All elements of the work have been numbered, ranging from 1 to 26. No. 10 and nos. 18-26 have been left unfinished, because, after 8 years of working on the piece, Duchamp lost interest in completing it.

Duchamp states that his “hilarious picture” is intended to depict the erotic encounter between the Bride and her nine Bachelors. In this piece of art, his attitude is “pseudoscientific, mock-analytical”. While understanding this work, there are a few things to be taken into consideration. The Large Glass represents abstract forces through elements, indicating different allegories. The chain of events proceeds in a clockwise direction. For the following analysis, translations of Duchamp’s original notes, the Green Box, by Schwarz have been used, along with other sources that give us possible interpretations. We have put together an analysis based on the pre-decided meanings given to each component by Duchamp. It needs to be noted that nobody understands the Large Glass fully. Many a time, Duchamp’s notes are ambiguous and therefore incomprehensible. This makes it difficult to draw any conclusions about his true message.

The name of the picture, The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even refers to the Bride as the subject. The Bride is described by Duchamp as “Pendu Femelle, arbor-type” which literally translates as “hanging female, tree-type”. Examination shows that it does indeed hang from a painted hook at the top of the glass pane. References have been made to the Bride as being an “agricultural machine” or an “instrument for farming”, which could perhaps refer to the Bride’s fertility or even the act of childbirth. The Bride is essentially a motor, who runs on Love Gasoline, stored in the Reservoir and fed to the Quite Feeble Cylinders. These Cylinders control the upper portion of the Bride. To the right of these structures lies the Wasp or the Sex Cylinder, a flask-shaped object that narrows at the top and is capped by a pair of snail-like antennae. In the words of Duchamp, the Wasp has the following properties: “Secretion of the Love Gasoline through osmosis; A certain flair or sense of unbalance from the black ball in relation to the Pendu’s upper part; the vibratory property of the Wasp is responsible for the pulsations of the needle; Ventilation, which is required for the swinging of the Pendu and its accessories.” The term ‘wasp’ implies a possible symbolic interpretation, as prevalent in Arabian and European cultures. The Arabian culture interprets wasps as temptations to be resisted, while stings imply grief-filled days. In European culture, a wasp itself is a sign of laziness, damage, malice, dangerous attacks on unknown enemies, whereas the killed wasp shows the ability to stand up fearlessly against the opponent. The second aspect of the title of this “delay in glass” is focused mainly on the Bride’s “mise à nu” (exposure), referring to her body’s uncovering. The Bride’s nudity occurs twice; firstly through the stripping by the Bachelors (an electric process), and secondly through her “voluntary-imaginative” stripping through sparks from her own Desire-Magneto. A magneto is a small electric generator containing a magnet, used to provide high-voltage pulses.

The nine Bachelors, also called as the Malic Moulds or Eros’s Matrix dominate the lower glass pane. They resemble the empty carcasses of clothes hanging from a clothesline, much more than they do actual men. Painted dark brown, all of them have a central vertical line while some have a horizontal line within. Every Bachelor has a different profession—Priest, Busboy, Policeman, etc. These Bachelors have two key functions—to transmit commands to the Bride through an electric process and to receive an Illuminating Gas, which animates them. This Gas, previously termed Love Gasoline, is presumably given by the Bride, although Duchamp does not explicitly state so. There is no depiction of the Illuminating Gas or Love Gasoline being received by the Bachelors, perhaps because it is shown in its later stages—when the Bachelors process it.

The Bride is shown free of all inhibitions with respect to her desire for sexual pleasure, as she penetrates into the Bachelor’s Domain, past the Horizon, with her Love Gasoline. Each of the nine Bachelors is destined to receive and homogenise it. The Bachelors absorb this gas which is then cut into unequal Spangles. They withstand the first process of homogenisation and retain the “malic tint”. The second round is initiated after the lighter-than-air Spangles reach the end of the Capillary Tubes, pipes that connect heads of the Bachelors to the Sieves. The Sieves are seven conical cylinders where the yet individuated Spangles, as Duchamp puts it, straighten out. Each cone is connected to the next cone’s base by its tip. This connection of cones forms a half-circle. The amalgamation of the multiple Spangles turns into a dense and dissolved liquid, the Bachelor Fluid. This causes maturation in their opacity, from an embryonic light beige to a saturated dark brown. This coalescence symbolises the Bachelors’ lack of free will and determination, where they are deprived of their individual qualities despite coming from a variety of fields, solely to gain the Bride’s approval.

The Bachelor Fluid exits the Sieves in a single stream shaped like a Spiral and rebounds in a Splash, splitting into nine distinct spurts. The Splash exemplifies the erotic impulses of the Bachelors. It could refer to seminal fluid, a flirtatious glance or a marriage proposal.

The end of this Spiral is aligned such that the scattered Fluid can pass through a structure towards the upper right-hand corner of the Bachelor Apparatus, the Oculist Witnesses. The Oculist Witnesses are four hollow circular structures. The lower three, placed three-dimensionally, display an identical radius. The first one from the top, smallest of all, is a perfect circle. The second has twelve spokes, each spoke consisting of three lines. The middle is made of six concentric circles. At the bottom is hollow circle surrounded by radiating outward lines.

Duchamp constructs a machine, the Glider, with cheap and fragile materials such as tin, cords, iron wire, and crude wooden pulleys. According to Duchamp, the Glider is a “flimsy metallic construction on elliptical runners” and slides back and forth at random. The device is similar to a “waterwheel with spokes of a bicycle wheel”. The Glider is a symbol for the slow and vicious cycle of the lives lived by the suffering Bachelors, characterised by onanism and a monotonous will—to rebound their “junk of life” through the Glider.

The Chocolate Grinder, which includes three barrel-like structures coloured chocolate-brown, is sandwiched between a stool and a circular mounting. They have evenly spaced lines running all over the cylinders. The Chocolate Grinder symbolises the principle of spontaneity according to Duchamp, which explains its independent “gyratory movement”. In his notes, he expresses his intent to label it as the Chocolate Grinder on a glossy and coloured paper, specially made by a printer, to signify the commercialised chocolate that is ground by the Bachelors themselves. This analogy could denote the mass production of millions of Bachelors who follow tested recipes to get a Bride, who is rather unconventional and indifferent to these ancient tactics.

A pole sprouts from the centre of the Chocolate Grinder, on which rest two metal rods that form a large X, the Scissor. The Scissor is affixed to the Glider through another pair of metal rods. The Scissor’s movement is supported by the Chocolate Grinder and powered by the Glider.

The Cinematic Blossoming is identified with numerous other terms as the Halo of the Bride, Top Inscription and Milky Way. It is partially overlapped by the Bride’s body on the left. The Halo is a cinematic representation of the Bride at the moment of her blossoming, simultaneous with the moment of her stripping. It is a monochromatic cloud-like structure with a curvilinear outline. Three irregularly shaped exposures of Draft Pistons or Nets hang on it with the aid of a hook. The title of this element comes from one of Duchamp’s previous works, Draft Piston (1914), which is a photograph of a plane of square gauze or netting material (possibly a wedding veil) in front of an open window that assumes different shapes when moved about by air drafts. As Duchamp explains: “I wanted to register the changes in the surface of that square and use in my Glass the curves of the lines distorted by the wind. So I used a gauze, which has natural straight lines. When at rest, the gauze was perfectly square—like a chessboard—and the lines perfectly straight—as in the case of graph paper.” Through these Nets, the Bride expresses her wants to the Bachelors. Unfortunately for the Bachelors, these demands are expressed in an encrypted language. Symbols are grouped, where each symbol within the grouping is unique and representative of a desire. According to Duchamp’s notes on the formation of these symbols, each grouping must be thought of as the letters of the “new alphabet”. Each grouping is related to each other by a “strict meaning”. According to Andrew Stafford in his blog dedicated to Duchamp, the Halo represents the Bride’s dreams, romantic and erotic, waiting to be fulfilled by a successful suitor.

The Draft Pistons or Nets within the Halo are like voids in her dreams, opportunities for suitors to strike the Nets, proceeding which the Bride will plunge into the Bachelors’ “earthbound domain”. The Scissor’s random movement gives rise to two distinct situations; the trajectory of the Splash either disrupted or missed by its merciless blades at the Oculist Witness at the top—upon disruption, the Splash falls deeper into the Bachelors’ Apparatus, eventually disappearing into thin air. When missed, the Splash manages to cross the Horizon and enter the Bride’s Domain.

Ultimately when the Splash is missed by the trajectory of the Scissor, the Bachelors temporarily leave their impression on the top left of the Bride’s Domain, termed as the Nine Shots. The creation of this element was purely based on the chance factor. Duchamp, using paint-tipped matches and a toy cannon, aimed shots at a target point, the Draft Pistons. Having missed the Nets indicates that the Bachelors, despite their strenuous effort, fail. The failure denotes a considerable miscalculation and misinterpretation of the Bride’s desires by the Bachelors.

Duchamp, after a point, left the piece “definitively unfinished”, hence omitting a number of essential elements that would go on to produce a complete chain of events. For example, the Juggler who acts in response to impulses from the Bride, and the Boxing Match which seemingly obstructs the Bachelor Fluid attempt to cross the Horizon.

The idea of the Bride being stripped by the Bachelors causes discomfort to the spectators of the painting, and indeed the Bride’s nature is ambiguous. Though the Bride remains passive by not retaliating against the Electrical Stripping, Duchamp notes that she has a strong desire for an orgasm as well. She is the one truly in control, by showing acceptance towards the stripping by the Bachelors as she furnishes the Love Gasoline and in fact assists them in her stripping by “developing in a sparkling fashion”. According to Calvin Tomkins in his book on Duchamp’s life and works, the Bachelors, by contrast, are “wholly passive”, as they accept and act according to the Bride’s desires.

If the artist is to decide what art is, it is completely in his control to label anything and everything as art. Duchamp valued an artwork’s philosophical complexity (expressed through symbolism and subjective interpretations) over its materialist complexity (expressed through the degree of skill in the painting techniques). Given such vexed freedom, does art even exist? How does one, including the artist, distinguish the ordinary from the unordinary?

0 notes

Text

CULTURE: A brief understanding of polyamory

The fundamental question—“what is love”—is bound to pop up in your head unless you are lucky enough to find your “soulmate” who you vow to love unconditionally till death do you part. While the larger population seems to believe in monogamy, pop culture manifests in itself dilemmatic situations of love affairs that appropriately deviate from the norm. The definitions of love and the lover are in a visible flux for individuals, if not societies at large, causing the resurfacing of old, buried practices and the emergence of new ones. The advocates of polyamory believe that one can express love without confining to the boundaries of monogamy. Nonconsensual Non-Monogamy (e.g. extra-marital affairs) is different from the practice of polyamory or consensual Non-Monogamy wherein mutual consent is an uncompromisable prerequisite.

The Question of Love

Most research on love has revealed two distinct forms of love—companionship (sometimes called comfort or attachment love) and passionate or romantic love. Passionate love is mainly characterised by intense emotional arousal, desire for “union” with the beloved and sexual attraction for the beloved. Comfort love is seen as the departure from the temporary passionate love. It is characterised by a sense of friendship, empathetic understanding and deep affection (Jankowiak & Gerth, 2012). Extending upon J. A. Lee’s work (1973/1976) research done by Hendrick & Hendrick provides a multifaceted view of love, thereby including 6 basic love styles; Eros (passionate love); ludus (game-playing love); storge (friendship love); pragma (practical love); mania (possessive, dependent love); and agape (altruistic love).

The definition of love has perennially troubled scholars and tortured musicians alike, and any attempt to objectively define it has only led to subjective interpretations that serve a practical purpose for existing beliefs. Polyamorists and monogamists come from different viewpoints about love and its expression. Monogamists believe that love can only be expressed between the confines of a dyadic bond. Further, its expression can be condensed into either erotic love (sexual expression) and companionate love (emotional intimacy). While monogamy refrains partners from engaging in sexual activity with anyone outside the relationship, platonic emotional intimacy is non-threatening for either partner. In contrast, polyamory, as explained through various texts, give uncompromising importance to both erotic and companionate love. Given the broader definition of love, polyamorists would consider having deep emotional intimacy with a person outside of a relationship as loving another person, irrespective of whether it culminates into a sexual relationship or not. Dossie Easton and Janet W. Hardy (Easton & Hardy, 2009, p.47) write:

If you have a lover and a best friend who are not the same person, you’re already practicing many of the skills of sluthood as you manage each of their needs for intimacy, time, and affection.

Non-monogamous relationships can take multiple forms including serial pair-bonding, polygamy, polyandry, communal living, and “open” pair-bondings, where sexual or sexual-emotional relationships outside of the primary one are tolerated to a greater or lesser degree. Polyamory as a term was first published in the May 1990 issue of Green Egg in an article, “Bouquet of Lovers” by Morning Glory Zell-Ravenhart, describing it as “the custom or practice of engaging in multiple sexual [or, for some, romantic] relationships with the knowledge and consent of all partners concerned” (Zell, 1990). Polyamory can be defined as a practice that does not put any restrictions on loving more than one person simultaneously, although individuals manifest this basic principle into their practice of polyamory in multiple ways.

While monogamy works for many, it is not adequate enough to fulfill the intimacy needs of some individuals (Peabody, 1982). Multiple scholars have ferociously critiqued marriage as an institution, inadvertently scrutinising mononormativity These arguments usually work in favour of polyamory as a viable alternative. Although most studies do not advocate the practice as ferociously, it is safe to assume that these scholars incline towards it. Monogamy works on a basic claim that a relationship is built on a form of unsurpassed affection which is intrinsically virtuous and of value to the society. Research, on the contrary, shows that this form of “unsurpassed affection” is indeed achievable within non-monogamy. Rubel and Bogaert (2014) found scant evidence for differences in psychological well-being and relationship quality for monogamist and non-monogamists. Study on CNM and monogamous participants reported no significant difference in their level of relationship and sexual satisfaction (Wood, Desmarais, Burleigh, & Milhausen, 2018). This finding is consistent with those of several other recent studies (i.e., Conley et al., 2017;Parsons et al., 2012; Rubel & Bogaert, 2014; Séguin et al., 2016) that have examined the aspects of relational quality among gay male, CNM, polyamorous, and monogamous couples. Sternberg’s (1997) study on multi-person relationships suggests that loving more than one person assumes a hierarchical structure, the sustenance of which would only bring forth emotional turmoil and painful internal conflict. A recent study by Jiang (2017) suggests that passionate love and emotional jealousy is higher for primary partners. On the contrary, some studies indicate that relationship qualities based on the monogamist or non-monogamist status may differ. For instance, polyamorous individuals reported greater levels of intimacy compared to mono-amorous participants (Morrison, Beaulieu, Brockman, & O’Beaglaoich, 2013).

1 note

·

View note