#biblical interpretation

Text

There's a curious but popular notion circulating around the church these days that says God would never stoop to using ancient genre categories to communicate. Speaking to ancient people using their own language, literary structures, and cosmological assumptions would be beneath God, it is said, for only our modern categories of science and history can convey the truth in any meaningful way.

In addition to once again prioritizing modern, Western (and often uniquely American) concerns, this notion overlooks one of the most central themes of Scripture itself: God stoops. From walking with Adam and Eve through the garden of Eden, to traveling with the liberated Hebrew slaves in a pillar of cloud and fire, to slipping into flesh and eating, laughing, suffering, healing, weeping, and dying among us as part of humanity, the God of scripture stoops and stoops and stoops and stoops. At the heart of the gospel message is the story of a God who stoops to the point of death on a cross.

Dignified or not, believable or not, ours is a God perpetually on bended knee, doing everything it takes to convince stubborn and petulant children that they are seen and loved. It is no more beneath God to speak to us using poetry, proverb, letters, and legend than it is for a mother to read storybooks to her daughter at bedtime. This is who God is. This is what God does.

—Rachel Held Evans, Inspired, p.11-12

#rachel held evans#christianity#biblical interpretation#god#progressive christian#the bible#christian#bible#quotes#episcopalian

618 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wrestling with the Bible's war stories

Spend any solid amount of time with scripture and you'll run into something that perplexes, disturbs, or downright horrifies you. Many of us have walked away from the Bible or from Christianity in general, sometimes temporarily and sometimes permanently, after encountering these stories. So how do we face them, wrestle them, and seek God's presence in (or in spite of) them?

In her book Inspired: Slaying Giants, Walking on Water, and Loving the Bible Again, the late Rachel Held Evans spends a whole chapter on the "war stories" of Joshua, Judges, and the books of Samuel and Kings. She starts with how most teachers in her conservative Christian upbringing shut her down every time she tried to name the horror she felt reading of violence, rape, and ethnic cleansing; I share an excerpt from that part of the chapter over in this post.

That excerpt ends with Evans deciding that she needed to grapple with these stories, or lose her faith entirely.

...But then I ended the excerpt, with the hope that folks would go read all of Inspired for themselves — and I still very much recommend doing so! The whole book is incredibly helpful for relearning how to read scripture in a way that honors its historical context and divine inspiration, and takes seriously how misreadings bring harm to individuals and whole people groups.

But I know not everyone will read the book, for a variety of reasons, and that's okay. So I want to include a long excerpt from the rest of the chapter, where Evans provides cultural context and history that helps us understand why those war stories are in there; and then seeks to find where God's inspiration is among those "human fingerprints."

I know how important it was to Rachel Held Evans that all of us experience healing and liberation, so it is my hope that she'd be okay with me pasting such a huge chunk of the book for reading here. If you find what's in this post meaningful, please do check out the rest of her book! A lot of libraries have it in print, ebook, and/or audiobook form.

[One last comment: the following excerpt focuses on these war stories from the Hebrew scriptures ("Old Testament"), but there are violent and otherwise disturbing stories in the "New Testament" too, from Herod killing babies to all the wild things going on in Revelation. Don't fall for the antisemitic claim that "The Old Testament is violent while the New Testament is all about peace!" All parts of scripture include violent passages, and maintain an overarching theme of justice and love.]

Here's the excerpt showing Rachel's long wrestling with the Bible's war stories, starting with an explanation for why they're in there in the first place:

“By the time many of the Bible’s war stories were written down, several generations had passed, and Israel had evolved from a scrappy band of nomads living in the shadows of Babylon, Egypt, and Assyria to a nation that could hold its own, complete with a monarchy. Scripture embraces that underdog status in order to credit God with Israel’s success and to remind a new generation that “some trust in chariots and some in horses, but we trust in the name of the LORD our God” (Psalm 20:7). The story of David and Goliath, in which a shepherd boy takes down one of those legendary Canaanite giants with just a slingshot and two stones, epitomizes Israel’s self-understanding as a humble people improbably beloved, victorious only by the grace and favor of a God who rescued them from Egypt, walked with them through the desert, brought the walls of Jericho down, and made that shepherd boy a king.

To reinforce the miraculous nature of Israel’s victories, the writers of Joshua and Judges describe forces of hundreds defeating armies of thousands with epic totality. These numbers are likely exaggerated and, in keeping literary conventions of the day, rely more on drama and bravado than the straightforward recitation of fact. Those of us troubled by language about the “extermination” of Canaanite populations may find some comfort in the fact that scholars and archaeologists doubt the early skirmishes of Israel’s history actually resulted in genocide.

It was common for warring tribes in ancient Mesopotamia to refer to decisive victories as “complete annihilation” or “total destruction,” even when their enemies lived to fight another day. (The Moabites, for example, claimed in an extrabiblical text that after their victory in a battle against an Israelite army, the nation of Israel “utterly perished for always,” which obviously isn’t the case. And even in Scripture itself, stories of conflicts with Canaanite tribes persist through the book of Judges and into Israel’s monarchy, which would suggest Joshua’s armies did not in fact wipe them from the face of the earth, at least not in a literal sense.)

Theologian Paul Copan called it “the language of conventional warfare rhetoric,” which “the knowing ancient Near Eastern reader recognized as hyperbole.”

Pastor and author of The Skeletons in God’s Closet, Joshua Ryan Butler, dubbed it “ancient trash talk.”

Even Jericho, which twenty-first-century readers like to imagine as a colorful, bustling city with walls that reached the sky, was in actuality a small, six-acre military outpost, unlikely to support many civilians but, as was common, included a prostitute and her family. Most of the “cities” described in the book of Joshua were likely the same. So, like every culture before and after, Israel told its war stories with flourish, using the language and literary conventions that best advanced the agendas of storytellers.

As Peter Enns explained, for the biblical writers, “Writing about the past was never simply about understanding the past for its own sake, but about shaping, molding and creating the past to speak to the present.”

“The Bible looks the way it does,” he concluded, “because God lets his children tell the story.”

You see the children’s fingerprints all over the pages of Scripture, from its origin stories to its deliverance narratives to its tales of land, war, and monarchy.

For example, as the Bible moves from conquest to settlement, we encounter two markedly different accounts of the lives of Kings Saul, David, and Solomon and the friends and enemies who shaped their reigns. The first appears in 1 and 2 Samuel and 1 and 2 Kings. These books include all the unflattering details of kingdom politics, including the account of how King David had a man killed so he could take the man’s wife, Bathsheba, for himself.

On the other hand, 1 and 2 Chronicles omit the story of David and Bathsheba altogether, along with much of the unseemly violence and drama around the transition of power between David and Solomon.

This is because Samuel and Kings were likely written during the Babylonian exile, when the people of Israel were struggling to understand what they had done wrong for God to allow their enemies to overtake them, and 1 and 2 Chronicles were composed much later, after the Jews had returned to the land, eager to pick up the pieces.

While the authors of Samuel and Kings viewed the monarchy as a morality tale to help them understand their present circumstances, the authors of the Chronicles recalled the monarchy with nostalgia, a reminder of their connection to God’s anointed as they sought healing and unity. As a result, you get two noticeably different takes on the very same historic events.

In other words, the authors of Scripture, like the authors of any other work (including this one!), wrote with agendas. They wrote for a specific audience from a specific religious, social, and political context, and thus made creative decisions based on that audience and context.

Of course, this raises some important questions, like: Can war stories be inspired? Can political propaganda be God-breathed? To what degree did the Spirit guide the preservation of these narratives, and is there something sacred to be uncovered beneath all these human fingerprints?

I don’t know the answers to all these questions, but I do know a few things.

The first is that not every character in these violent stories stuck with the script. After Jephthah sacrificed his daughter as a burnt offering in exchange for God’s aid in battle, the young women of Israel engaged in a public act of grief marking the injustice. The text reports, “From this comes the Israelite tradition that each year the young women of Israel go out for four days to commemorate the daughter of Jephthah” (Judges 11:39–40).

While the men moved on to fight another battle, the women stopped to acknowledge that something terrible had happened here, and with what little social and political power they had, they protested—every year for four days. They refused to let the nation forget what it had done in God’s name.

In another story, a woman named Rizpah, one of King Saul’s concubines, suffered the full force of the monarchy’s cruelty when King David agreed to hand over two of her sons to be hanged by the Gibeonites in an effort to settle a long, bloody dispute between the factions believed to be the cause of widespread famine across the land. A sort of biblical Antigone, Rizpah guarded her sons’ bodies from birds and wild beasts for weeks, until at last the rain came and they could be buried. Word of her tragic stand spread across the kingdom and inspired David to pause to grieve the violence his house had wrought (2 Samuel 21).” ...

The point is, if you pay attention to the women, a more complex history of Israel’s conquests emerges. Their stories invite the reader to consider the human cost of violence and patriarchy, and in that sense prove instructive to all who wish to work for a better world. ...

It’s not always clear what we are meant to learn from the Bible’s most troubling stories, but if we simply look away, we learn nothing.

In one of the most moving spiritual exercises of my adult faith, an artist friend and I created a liturgy of lament honoring the victims of the texts of terror. On a chilly December evening, we sat around the coffee table in my living room and lit candles in memory of Hagar, Jephthah’s daughter, the concubine from Judges 19, and Tamar, the daughter of King David who was raped by her half brother. We read their stories, along with poetry and reflections composed by modern-day women who have survived gender-based violence. ...

If the Bible’s texts of terror compel us to face with fresh horror and resolve the ongoing oppression and exploitation of women, then perhaps these stories do not trouble us in vain. Perhaps we can use them for some good.

The second thing I know is that we are not as different from the ancient Israelites as we would like to believe.

“It was a violent and tribal culture,” people like to say of ancient Israel to explain away its actions in Canaan. But, as Joshua Ryan Butler astutely observed, when it comes to civilian casualties, “we tend to hold the ancients to a much higher standard than we hold ourselves.” In the time it took me to write this chapter, nearly one thousand civilians were killed in airstrikes in Iraq and Syria, many of them women and children. The atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki took hundreds of thousands of lives in World War II, and far more civilians died in the Korean War and Vietnam War than American soldiers. Even though America is one of the wealthiest countries in the world, it takes in less than half of 1 percent of the world’s refugees, and drone warfare has left many thousands of families across the Middle East terrorized.

This is not to excuse Israel’s violence, because modern-day violence is also bad, nor is it to trivialize debates over just war theory and US involvement in various historical conflicts, which are complex issues far beyond the scope of this book. Rather, it ought to challenge us to engage the Bible’s war stories with a bit more humility and introspection, willing to channel some of our horror over atrocities past into questioning elements of the war machines that still roll on today.

Finally, the last thing I know is this: If the God of the Bible is true, and if God became flesh and blood in the person of Jesus Christ, and if Jesus Christ is—as theologian Greg Boyd put it—“the revelation that culminates and supersedes all others,” then God would rather die by violence than commit it.

The cross makes this plain. On the cross, Christ not only bore the brunt of human cruelty and bloodlust and fear, he remained faithful to the nonviolence he taught and modeled throughout his ministry. Boyd called it “the Crucifixion of the Warrior God,” and in a two-volume work by that name asserted that “on the cross, the diabolic violent warrior god we have all-too-frequently pledged allegiance to has been forever repudiated.” On the cross, Jesus chose to align himself with victims of suffering rather than the inflictors of it.

At the heart of the doctrine of the incarnation is the stunning claim that Jesus is what God is like. “No one has ever seen God,” declared John in his gospel, “but the one and only Son, who is himself God and is in closest relationship with the Father, has made him known” (John 1:18, emphasis added). ...So to whatever extent God owes us an explanation for the Bible’s war stories, Jesus is that explanation. And Christ the King won his kingdom without war.

Jesus turned the war story on its head. Instead of being born to nobility, he was born in a manger, to an oppressed people in occupied territory. Instead of charging into Jerusalem on a warhorse, he arrived on a lumbering donkey. Instead of rallying troops for battle, he washed his disciples’ feet. According to the apostle Paul, these are the tales followers of Jesus should be telling—with our words, with our art, and with our lives.

Of course, this still leaves us to grapple with the competing biblical portraits of God as the instigator of violence and God as the repudiator of violence.

Boyd argued that God serves as a sort of “heavenly missionary” who temporarily accommodates the brutal practices and beliefs of various cultures without condoning them in order to gradually influence God’s people toward justice. Insofar as any divine portrait reflects a character at odds with the cross, he said, it must be considered accommodation. It’s an interesting theory, though I confess I’m only halfway through Boyd’s 1,492 pages, so I’ve yet to fully consider it. (I know I can’t read my way out of this dilemma, but that won’t keep me from trying.)

The truth is, I’ve yet to find an explanation for the Bible’s war stories that I find completely satisfying. If we view this through Occam’s razor and choose the simplest solution to the problem, we might conclude that the ancient Israelites invented a deity to justify their conquests and keep their people in line. As such, then, the Bible isn’t a holy book with human fingerprints; it’s an entirely human construction, responsible for more vice than virtue.

There are days when that’s what I believe, days when I mumble through the hymns and creeds at church because I’m not convinced they say anything true. And then there are days when the Bible pulls me back with a numinous force I can only regard as divine, days when Hagar and Deborah and Rahab reach out from the page, grab me by the face, and say, “Pay attention. This is for you.”

I’m in no rush to patch up these questions. God save me from the day when stories of violence, rape, and ethnic cleansing inspire within me anything other than revulsion. I don’t want to become a person who is unbothered by these texts, and if Jesus is who he says he is, then I don’t think he wants me to be either.

There are parts of the Bible that inspire, parts that perplex, and parts that leave you with an open wound. I’m still wrestling, and like Jacob, I will wrestle until I am blessed. God hasn’t let go of me yet.

War is a dreadful and storied part of the human experience, and Scripture captures many shades of it—from the chest-thumping of the victors to the anguished cries of victims. There is ammunition there for those seeking religious justification for violence, and solidarity for all the mothers like Rizpah who just want an end to it.

For those of us who prefer to keep the realities of war at a safe, sanitized distance, and who enjoy the luxury of that choice, the Bible’s war stories force a confrontation with the darkness.

Maybe that’s not such a bad thing.

#joshua#biblical interpretation#texts of terror#rachel held evans#inspired#wrestling god#reading and studying the bible#bible tag#long post#quote tag

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theological Implications of Jesus' Resurrection for Salvation

Jesus’ resurrection is an essential element in soteriology. In fact, every writer of the NT assumes that Jesus was resurrected from the grave and treat it as an event that took place in time and space. Paul wrote that Jesus “was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures” (1 Cor 15:4), that He was “the first fruits of those who are asleep” (1 Cor 15:20), and that “having been raised from…

View On WordPress

#Apologetics of Faith#atonement#Biblical Apologetics#Biblical Exegesis#Biblical interpretation#Biblical theology#Biblical Witnesses#Christian apologetics#Christian beliefs#Christian doctrine#Christian faith#Christian Hope#Christian living#Christian salvation#Christian theology#crucifixion#Divine Atonement#Early Christian Beliefs#Easter#Easter Theology#faith#gospel message#Historical Jesus#how important is the resurrection of Jesus#importance of Jesus resurrection#is resurrection important#is the resurrection essential to the gospel#Jesus Christ#Jesus resurrection#justification

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

so do you believe the world is only 6000 years old?

No, I believe it is poetic. Many Catholics believe in evolution and it does not directly contradict our beliefs. Since light was created on the fourth day there is no way to determine what the length of time was on the first three days.

I discussed this briefly when talking about the Pontifical Bible Commission's 5 unacceptable assumptions found in scriptural interpretation.

#anonymous#5 Unacceptable Assumptions#Biblical interpretation#Catholic#Christian#Christianity#religion

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have observed that it's not that there's a lack of biblical basis regarding their man made traditions/beliefs, doctrines etc. It's that they have taken Scripture out of context, isolating it and treating a verse/s as it's intended meaning without considering other correlating verses. It's that they've taken scriptures and most often the not, that those verses do not even display or support such beliefs, traditions, doctrines. It's biblical fallacy and perversion. If you think about Satan's temptation of Jesus Christ in the desert, in the period Jesus was fasting; Satan took and showed Him kingdoms and offered Him things. In that interaction we're shown that even Satan knew Scripture and completely took it out of context for his kind of reasoning yet Jesus refuted him with Scripture; showing that even when one verse says another, and it is true, you need to consider a correlating verse/s of which will give you a clearer view of it's intentional depiction. Many lack the wisdom or understanding to even interpret Scripture in a way that's not to glorify or support their selfish perceptions. Many lack the Holy Spirit's guidance as well as His counsel, and it's quite telling unfortunately.

#christianity#christblr#christian#jesus christ#christian faith#jesus#christian blog#spiritual enlightment#biblical fallacy#fallacy#biblical interpretation#biblical doctrine#understanding#wisdom#Holy Spirit

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

What’s really cool about studying Biblical interpretation is the understanding that the Bible is not the actual baseline foundation for the Church but rather the lens through which we can perceive the very beginnings of the Christian faith and community. This seems a subtle difference but if you’ve ever kept a journal or done a lot of personal writing, think of it this way: you’ve got three journals and some English assignments and a bit of fanfiction you wrote in 2010. And a story a close friend wrote about your possible futures and her poems she wrote on a vacation you took together. What do these things tell you about your life then? It’s not the same as the reality of your life but it probably conveys the most important gist of things if you look closely enough.

That’s what the Bible is for Christianity. Which is why it is so complicated to interpret and so vital to be interpreted in a meaningful and consistent-with-the-faith way. And why fundamentalism and literalism and personal subjective perspectives don’t just damage Christian reputation but actually work against the faith as a whole.

#biblical interpretation#Christianity#religion#currently reading the interpretation of the Bible in the church#pontifical biblical commission 1993

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Those who feel little or none of the work of God in their own hearts are not willing to allow that He works in others. Many deny the influences of God's Spirit, merely because they never felt them. This is to make any man's experience the rule by which the whole Word of God is to be interpreted; and consequently, to leave no more divinity in the Bible than is found in the heart of him who professes to explain it.

Adam Clarke

#this hits hard#biblical interpretation#the bible#Unbelief#Faith#Doubt#Lean not on your own understanding#This is very relevant to the world lately

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

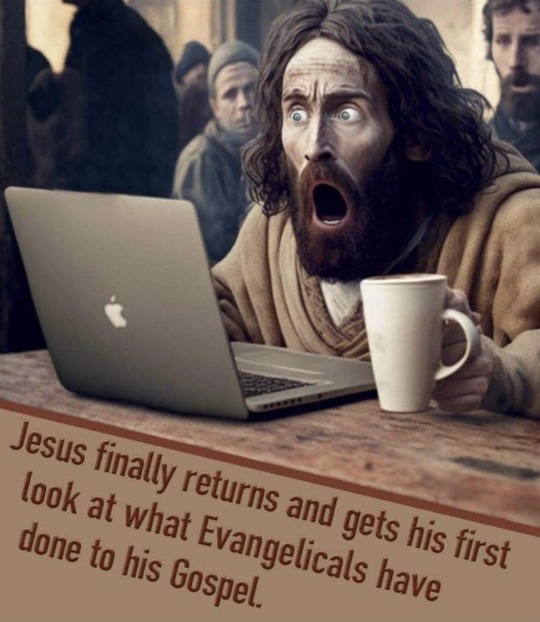

What if most Christians actually aren’t, and they don’t even know it?

This image floated across my Social Media, and it’s so dang funny that it has brought on a story for the weekend.

As a once-pastor of several differing Christian churches, the most common question I received was:

“Does God really hate gay people? Because it’s in the Bible.”

I would answer, “Where did you hear that God hated gay people?”

The usual answer was “Well God said ‘love the sinner,…

View On WordPress

#angels#anti-Christ#armageddon#bible#biblical#biblical interpretation#biblical study#book of revelations#Christ#christian#christianity#Compassion#Consciousness#does god hate gays#end of the world#end times#evangelical#faith#Fear Consciousness#finding hope#gay#god#God’s will#historical Jesus#history#homosexuality and the Bible#hope#jesus#learning#lesbian

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

French translation of Eli Kittim’s article

Traduction française de l'article d'Eli Kittim

——-

PREUVE QUE DANIEL 12.1 FAIT RÉFÉRENCE À UNE RÉSURRECTION D'ENTRE LES MORTS BASÉE SUR LA TRADUCTION ET L'EXEGÈSE DES LANGUES BIBLIQUES

Par l'auteur Eli Kittim

Daniel 12.1 se situe dans le contexte de la grande tribulation de la fin des temps ! Matthieu 24.21 en parle aussi comme le temps de la grande épreuve : καιρός θλίψεως (cf. Apocalypse 7.14).

Daniel Théodotion 12.1 LXX :

καὶ ἐν τῷ καιρῷ ἐκείνῳ ἀναστήσεται Μιχαηλ ὁ ἄρχων ὁ μέγας ὁ ἑστηκὼς ἐπὶ τοὺς υἱοὺς τοῦ λαοῦ σου καὶ ἔσται καιρὸς θλίψεως θλῖψις οἵα οὐ γέγονεν ἀφ’ οὗ γεγένηται ἔθνος ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς ἕως τοῦ καιροῦ ἐκείνου.

La Théodotion Daniel 12.1 de la Septante traduit le mot hébreu עָמַד (amad) par αναστήσεται, qui est dérivé de la racine du mot ανίστημι et signifie « se lèvera ».

Traduction:

À ce moment-là, Michel, le grand prince, le protecteur de ton peuple, se lèvera. Il y aura un temps d'angoisse, tel qu'il n'y en a jamais eu depuis que les nations ont vu le jour.

Mon affirmation selon laquelle le mot grec ἀναστήσεται ("se lèvera") fait référence à une résurrection d'entre les morts a été contestée par des critiques. Ma réponse est la suivante.

Le premier élément de preuve est le fait que Michel est mentionné pour la première fois comme celui qui « ressuscitera » (ἀναστήσεται ; Daniel Theodotion 12.1 LXX) avant la résurrection générale des morts (ἀναστήσονται ; l'ancien grec Daniel 12.2 LXX). Ici, il existe des preuves linguistiques solides que le mot ἀναστήσεται fait référence à une résurrection parce que dans le verset suivant (12.2) le même mot au pluriel (à savoir, ἀναστήσονται) est utilisé pour décrire la résurrection générale des morts ! En d'autres termes, si ce même mot signifie résurrection dans Daniel 12.2, alors il doit aussi nécessairement signifier résurrection dans Daniel 12.1 !

Le deuxième élément de preuve provient de la version grecque ancienne de Daniel de la Septante qui utilise le mot παρελεύσεται pour définir le mot hébreu עָמַד (amad), qui est traduit par « surgira ».

La version de la LXX de l'ancien grec Daniel 12.1 se lit comme suit :

καὶ κατὰ τὴν ὥραν ἐκείνην παρελεύσεται Μιχαηλ ὁ ἄγγελος ὁ μέγας ὁ ἑστηκὼς ἐπὶ τοὺς υἱοὺς τοῦ λαοῦ σου ἐκείνη ἡ ἡμέρα θλίψεως οἵα οὐκ ἐγενήθη ἀφ’ οὗ ἐγενήθησαν ἕως τῆς ἡμέρας ἐκείνης.

La version de la septante de Daniel en grec ancien démontre en outre que Daniel 12.1 décrit un thème de mort et de résurrection parce que le mot παρελεύσεται signifie « mourir » (mourir), indiquant ainsi le décès de ce grand prince au moment de la fin! Il plante le décor de sa résurrection alors que la forme dite « Theodotion Daniel » de la LXX comble les lacunes en utilisant le mot αναστήσεται, signifiant une résurrection corporelle, pour établir la période des derniers jours comme le temps pendant lequel cette figure princière sera ressuscitée d'entre les morts !

#the little book of revelation#elikittim#bible prophecy#end times#last days#bible study#biblical interpretation#Interprétation biblique#le Petit livre de la révélation#Études bibliques#Prophétie biblique#eschatologie biblique#derniers jours#temps de fin#Septante#lxx#ek#eli of kittim#apocalypse#Messie#mort et résurrection#Daniel 12:1#Théodotion Septante#Ancienne Septante grecque#traduction et exégèse#Langues bibliques#koinè grec#Éli Kittim#chercheur biblique#auteur publié

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bible is resistance literature.

In the case of the mutant creatures of Daniel and Revelation, [biblical beasts] represent the evils of oppressive empires.

It’s easy for modern-day readers to forget that the Bible was written by oppressed religious minorities living under the heels of powerful nation-states known for their extravagant wealth and violence. For the authors of the Old Testament, it was the Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Greek, and Persian Empires. For the authors of the New Testament, it was, of course, the massive Roman Empire. These various superpowers, which inflicted centuries of suffering upon the Jews and other conquered populations, became collectively known among the people of God as Babylon.

One of the most important questions facing the people who gave us the Bible was: How do we resist Babylon, both as an exterior force that opposes the ways of God and an interior pull that tempts us with imitation and assimilation? They answered with volumes of stories, poems, prophecies, and admonitions grappling with their identity as an exiled people, their anger at the forces that scattered and oppressed them, God’s role in their exile and deliverance, and the ultimate hope that one day “Babylon, the jewel of kingdoms, the pride and glory of the Babylonians, will be overthrown by God” (Isaiah 13:19).

It is in this sense that much of Scripture qualifies as resistance literature. It defies the empire by subverting the notion that history will be written by the wealthy, powerful, and cruel, insisting instead that the God of the oppressed will have the final word.

—Rachel Held Evans, Inspired: Slaying Giants, Walking on Water, and Loving the Bible Again, p. 118

#rachel held evans#episcopalian#christianity#christian#progressive christianity#progressive christian#lgbtq christian#lgbt christian#queer christian#leftist#bible study#biblical interpretation#the bible#bible#scripture#god

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trying to explain to a guy on Instagram that all text must necessarily contain ambiguity as per the nature of language and therefore everything must be interpreted and that the imperfection of a human mind is not an excuse to outsource interpretation to undefined religious bodies via popular consensus.

But he keeps implying that I’m a dishonest nymphomaniac wracked with religious guilt.

It’s the classic problem really.

#religion#instagram#from me#by me#Christianity#biblical interpretation#premarital sex#folk christianity

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

And another thing about Biblical interpretation:

stories in the bible are, by all accounts, the most reinterpretable mismash of symbols and ideas our culture has, past whatever the fuck "Omegaverse" is.

I come from what psychiatrists call "a very bad no good family 😟" so I find it genuinely comforting that so many biblical narratives are about the fucked up, truly horrific shit families do to their children, particularly when the most common narratives in mainstream American culture are sooner to blame "the youths" for their parents' sins than even begin to examine the unending cruelty of even our kindest institutions. Public school is a kid prison with more textbooks & worse funding.

Cain was the first murderer and I also totally, indisputably understand exactly why Abel had to die. The first murderer was as much a victim of circumstance as I am, the sole difference between us is that he struck his brother in a moment I did not. Did not have to, perhaps.

Like, yeah, that old shepherd DID commodify his daughters. Our culture HAS been treating women like objects for a very, very long time, and honestly a certain degree of carefully planned & executed Incredible Violence might be warranted, should it hasten a change in certain behaviors.

Tl;dr we should rewrite the bible. A lot. We should be chewing up and spitting that book back out as much as possible. Burn their demonic sacrosanctions and dance out better stories in the ashen rain.

0 notes

Text

Unlocking Faith, Works, and Belonging in the Bible

Hey there, fellow seekers of truth! Today, let’s dive right into one of the juiciest debates among believers: faith versus works, and the whole shebang about which parts of the Bible are relevant to us today. This post today is inspired by a sister in Christ that shared some dialogue today on this very topic.

So, picture this: you’re flipping through your Bible, and you stumble upon passages…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Does it scare you to think about what Satan is trying to do to your kids?

What are you doing to make sure he doesn’t? Are you teaching your children about God?

Are you setting an example for them showing them what faithfulness looks like? Do you take them to church and Bible class?

Do you talk to them about the lies and immorality that the devil has made normal?

Do you keep them from playing video games and watching shows that slip in things that will take them off course? Do you pray for them and over them?

Don’t think for one second that you can let up or slack off. Evil doesn’t.

#Scripture#Holy Book#Christian Faith#Religious Text#Old Testament#New Testament#Gospel#Jesus Christ#Divine Revelation#Word of God#Biblical Stories#Salvation#Faith and Belief#Ten Commandments#Christian Doctrine#Prophets#Miracles#Redemption#Christian Ethics#Biblical Interpretation#today on tumblr

1 note

·

View note

Text

God wants to build a house.

#church#God's House#God#Jesus#Bible#bible reading#bible study#bibletruth#biblical interpretation#biblical theology#christian#scripture#christianity

0 notes