#genre: fairy tale

Link

by SteepedFoxgloveTea

Sabine comes across a white wolf in the forests of Peridea.

Words: 1016, Chapters: 1/1, Language: English

Fandoms: Star Wars - All Media Types, Star Wars: Ahsoka (TV)

Rating: Teen And Up Audiences

Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings, No Archive Warnings Apply

Categories: F/F

Characters: Sabine Wren, Shin Hati, Ahsoka Tano, Baylan Skoll

Relationships: Shin Hati/Sabine Wren, Ahsoka Tano & Sabine Wren, Shin Hati & Baylan Skoll

Additional Tags: Fairy Tale Elements, Inspired by Wolfwalkers (2020), Alternate Universe - Shapeshifters, Sabine Wren Needs a Hug, Shin Hati Needs A Hug, Secret Identity, Slow Burn, Tags May Change

#SteepedFoxgloveTea#shin hati/sabine wren#WolfWren#Ahsoka#shin hati#sabine wren#Rated: T#word count: 1k - 3k#genre: fairy tale#ao3feed

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Snow Maiden, Viktor Vasnetsov, 1899

#art#art history#Viktor Vasnetsov#genre painting#genre art#Snow Maiden#snegurochka#Russian folklore#fairy tales#Russian fairy tales#Russian art#19th century art#oil on canvas#Tretyakov Gallery

486 notes

·

View notes

Text

genre swap: snow white as a gothic horror, requested by anon

the snow is cold, the blood is warm, and snow lives in the crypt with seven ghosts.

#snow white#snow white and the seven dwarfs#fairy tale#fairytaleedit#fairy tale edit#photoshop hard#genre swap#blood tw

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

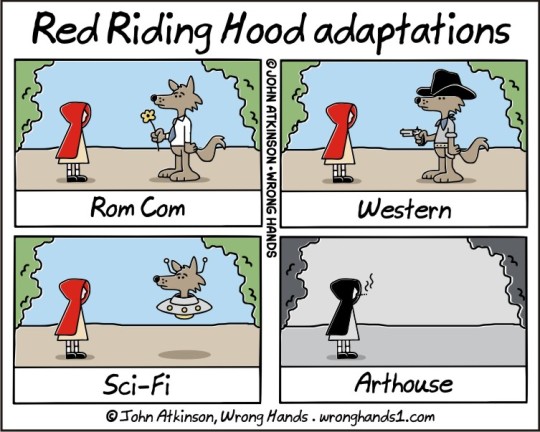

#red riding hood#adaptation#fairy tales#movies#genres#films#cinema#literature#reading#john atkinson#webcomic#wronghands

100 notes

·

View notes

Note

i was thinking about your dirk and hal poll and i want to mention that i think your concept for ink and iron where dirk creates hal from his reflection by enchanting a mirror is so cool 😌

thank you! hal's predicament and purpose within the canon narrative is so fascinating and i felt it was really important to find a way to explore what i find most interesting with him. i can't take full credit for the concept though i took inspiration from a few placees (one of my friends pitched the idea of the mirror accidentally dumping him onto jake's doorstop for example) but overall i think the idea is very fun and i'm really excited to write more hal stuff!!! also i'm going to take the opportunity to share this oldish doodle i found:

the mispelling of angel as angle was NOT intentional (<- dyslexia haver) but it probably explains a lot. he's pointy

#obviously an AU is going to be different from canon#but i like AUs specifically *because* i have a lot of fun trying to translate canon ideas into another setting or genre in general#in this case its a riff on the fairy tale magic mirror#hal is still an experiment gone wrong/artificial being created to serve a purpose trapped in a non-physical form and denied personhood#as well as being an extension of dirk's selfhood and very literal expression of his self image#this time with extra gender problems as per my original intentions for the fic. which now feel more than a bit heavy handed but whatever#point is hal gets to play up the trapped demon/spirit/almost genie-esque angle isntead of the artificial intelligence schtick in canon#which i am having a lot of fun writing!#he is also a very important plot device. multitalented 💕#for anyone wondering i&i is NOT an abandoned project its just huge and whipping it into shape is slow going#i've taken breaks to work on other stuff too#ink and iron#i guess that's a tag i should start using#even though i'm not too happy with the title still. lmao

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seriously what's w manhwa fans and cross-tagging? Do they not know how tumblr works or do they just not care?

I'm gonna start reporting every cross-tagged post I see under the “spam” umbrella.

Oh to not commit the same crime of cross-tagging myself I'm gonna make a list of which manhwas I have an AU of and which ones I don't.

The ones I have an AU for:

Who Made Me A Princess (my very first!)

Doctor Elise (unfortunately severely neglected no matter how fond I am of the AU somebody pls talk to me about it)

When The Villainess Loves (I have the basic premise down)

Villains Are Destined To Die (second biggest AU among my manhwa stuff)

The Villainess Reverses The Hourglass (kinda)

I Will Master This Family (ehhhh I probably need to rework it)

Actually I Was The Real One (Cosette I love you)

Beware of the Villainess (only beginning to form as I reread)

The ones I don't have an AU for:

Another Typical Fantasy Romance (practically perfect I love you)

The Monstrous Duke's Adopted Daughter (the side stories weren't my cup of tea but the main story was chef's kiss)

The Villainess Flips The Script (how could I possibly improve upon perfection LOL that thing is fucking hilarious)

A Stepmother's Marchen (I don't feel compelled to create for it, the story's great as-is)

There's probably a couple I'm forgetting in the yay department and definitely a lot I'm forgetting in the nay department (I have. read a lot. a lot of them suck.), it's been a long time since I killed my own sideblog, but oh well. Here's what I got so far anyways.

#who made me a princess#suddenly became a princess one day#doctor elise#the royal lady with a lamp#royal lady with a lamp#when the villainess loves#when the villainess is in love#villains are destined to die#death is the only ending for a villainess#death is the only ending for the villainess#the villainess reverses the hourglass#the villainess turns the hourglass#i will master this family#i'll be the matriarch in this life#actually i was the real one#actually i was real#beware the villainess#beware of the villainess#another typical fantasy romance#the villainess flips the script#i will change the genre#a stepmother's marchen#fantasie of a stepmother#a stepmother's märchen#a stepmother's fairy tale#disclaimer these fandoms are not necessarily the ones perpetuating this HOWEVER#due to the aforementioned cross-tagging it's practically impossible to track down what manhwa a post is about unless I've already read it#consider this a warning from someone who mostly uses tumblr for other things#individual manhwa tags are NIGH UNUSABLE bc of this cross-tagging

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Her soul belongs to words and books. Every time she reads, she is home.”

#reading#books#reading is my therapy#gothic literature#fantasy#fairy tales#fiction#romance#thriller#I enjoy reading different genres

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stars and Shadows: A Fairy Tale

An extremely experimental piece I've decided to submit for @inklings-challenge.

If you wait patiently, there will come a day--in a month, in a year, in a hundred-thousand hopeful days--when you will stare outside into the deep blue-black of a cold winter night and not be able to tell the snowflakes from the stars. It will call to your heart and pull you from the warmth and light of home--wrapped up in coats and boots, scarves and gloves, and one thick woolen blanket thrown over your shoulders like a cloak--in the hope of becoming, even for a moment, a part of the beauty of this moment of creation.

The cold of night will bite your face and steal your breath, but in a moment, you will find yourself racing across the white expanse, snow crunching beneath your boots, soul expanding toward the shining heavens in one upward rush of joy. As soon as home and family are safely out of view, you will slow from your sprint and find yourself content to amble, and wonder, and be, with the shy, slender moon watching patiently above.

You will carry no light, for the world will be light, with the moon and the stars and the snow wrapping all the world in bright illumination. Your breath will shine before you in delicate white clouds, your very life made visible for the fragile, lovely thing it is. In the silence you will hear the snowflakes fall, hear the hushed sound of your footfalls, feel every beat of your strong and pulsing heart.

And then, if you close your eyes and listen long enough, just at the moment when your heart is near to breaking from the beauty of it all, you will hear a cry. For a moment you might think it a phantom of thought, your own soul giving voice to all the aching loveliness that surges through you, but then, you will hear it again. Over and over, thin and wailing, the cry of a child newly born horrified to find the world so great and cold.

The sound will travel like an arrow in that crisp, cold air, and you will follow it without hesitation--over a rise, down a hill, through a twisting stand of trees and countless banks of snow, and at last to an old well, such as you've only seen in illustrations--a construction of wood and stones, covered with moss and aged with time, that you can say with certainty was not there a day before.

Standing by that well will be, not an infant, but a child. A little girl three years old, reaching desperately for the rim of the well and crying for water. Everything about her--her skin, her hair, her eyes--will be white as the snow she stands in, and she will gleam faintly with the light of the stars above, and she will wear nothing but thin, white rags, torn at the edges and singed at the ends, a ragged line of ash the only color in her form.

You will notice all these things and think it strange, and then you will forget everything because the child is crying. You will find a wooden bucket on a chain by the well, and in sheer desperation you will throw it down, though there will be nothing but ice in an open well on a night so cold.

But to your shock, you will hear a splash, and you will pull up a bucket full of liquid water that looks like light itself. You will give it to the girl--you would not dream of taking even a drop for yourself--and she will drink with cupped hands and lapping tongue, and gaze at you with silent gratitude.

When she has drained the last drop, the faint gleam of light around her form will become a white glow. She will seem a bit taller--perhaps a bit older than you first assumed--and for the first time, she will seem to feel the cold. She will shiver and wail and curl in on herself, and you will suddenly understand--or at least bless--your mad impulse to take a blanket out into the night. You will take it from your shoulders and wrap it round her form, head to foot, with only her shining white face peering out. Then you will take her in your arms, settle her on one hip, and carry her across the vast expanse of snow toward your home.

It will be a long trip--you have walked a long way--and before you have gone far, the child will grow too heavy for your strength. You will look to her and find that the blanket you have wrapped around her no longer seems so large, and clings more closely to her form--like something between a deep blue dress and cloak--so you will feel safe in setting her on the ground and letting her walk beside you, her thin white hand in yours.

You will wonder for a moment if you've fallen into a dream, for all seems so strange and perfect--the light, the snow, this silent child--but the bite of the cold and the burn of your legs will assure you that you remain in the waking world. Yet you won't think to question the child--who or what she is, or from whence she arrived--because she is so like the snow and the light and the stars of this crisp, cold night--things that do not become, but simply are. Your wonder make peace with the night's mystery.

The way back will seem longer than you remember--the trees taller, the stars brighter, the air colder. The night will seem large and you so very small, but you will not be afraid, for there is one beside you too innocent for fear. You will walk in the tracks you left on your way, stretching between footfalls that seem much more distant than you expected. Yet the moon will look larger, and you will take comfort in that. You will need the comfort before long.

For just when you are in the very midst of the trees, you will hear a sound from the shadows--dark and dangerous, like the growl of a wolf or the rumble of a distant train. And then the shadows will seem to take shape, growing arms and legs, teeth and claws, and they will gather in a great black wall that blocks the way you mean to take.

The voice that speaks will be less of a voice, and more like the clench of fear in your chest, the monster that mocks you as you lay awake at midnight with all the shame and sorrows of your wasted youth.

We will have the child.

You will know that the voice promises death for disobedience, and you will know to the depths of your soul that you would rather die than obey. You will hold the child close, and she will cling to your neck, and you will sprint with all your strength back toward the well. The shadows will surge and swirl around you, grabbing at your clothes, tearing at your face, and once--only once--drawing blood that drips a red path upon the snow.

You will sprint through the snow and twine through the trees, each step seeming a mile, each moment a lifetime. The shadows will gather--closer, darker--and the light of the child in your arms will fade with fear.

At last, you will see the well at the base of the hill, seeming to shine in a circle of light. If you can reach it, you know, you will be safe--every childhood game seeming suddenly like training for this very moment.

And yet, at the very edge of the clearing--somehow you always knew this would happen--you will lose your footing and fall face-first into the snow. You will shield the child's face from the snow by holding her close, and you will shield her body with your own. The shadows will fall upon you, tearing you to pieces. Your very body will seem to dissolve in pain.

Through their snarling, the shadows will promise relief, if you will only relent--the child's life for yours. Not so great a sacrifice, is it, for a child you've known for mere minutes? These words will tear at your mind, but it is your heart that will reply, drawing strength for defiance from you know not where. And you will. not. move.

You will feel the night fading--the stars and the snow and even the cold growing distant, like some faraway world in which you have no part. Even the pain will seem like something happening long ago and far away to some ancient hero in a dusty, tattered book. Yet you will feel the child beneath you, her beating heart still alive against yours, and that hope will keep you clinging to the tatters of breath in your body.

Then, at last, there will be light. So bright that it blazes white even through your closed eyes. The shadows will crumble like ash, retreat like the dark from a flame, and the destruction of your battered form will cease. The child you shelter will cry with joy.

A gentle touch will lift your shoulder so you lay on one side, and attempt to pull the child from your arms.

With a cry of defiance, you will hold her with what remains of your strength.

But then a voice will flow through you, lovely and feminine, like water and winter and moonlight given tongue. Peace.

Peace will come, perfect and pure, and you will release the child without fear. But without her presence, your need for strength will fade, and all your pain will come rushing in upon you, dark and hot and crushing, and you will have no strength to hold it back.

Absurdly, you will be most aware of an all-consuming thirst. Tears will pour from you--precious, wasted droplets. Then it will be you, and not the child, who cries for water. Then it will be the child who will draw water from the well and put the shining liquid to your lips.

You will drink, and the first mouthful will bring the cold climbing back upon you. But you will welcome it as re-entry into this world, and drink deep, again and again, until you find yourself freezing, but wholly alive, your wounds as if they never were. You will sit and gaze up at a woman dressed in midnight blue, as white and glowing as the child, who clings to her as she would to a mother, and you will find yourself alight with the same glow.

You have served my daughter well, that lovely inner voice will say again. Come and be at peace.

She will turn your eyes toward the heavens, and offer you a place there in the shining light, far from the troubles of this dark world. It will draw you as the snowflakes drew you from the warmth of home, so many long moments ago. Yet you will find yourself standing, and bowing your head, and with utmost humility refusing the honor. You will not leave this world, be there ever so many shadows, while there is still more beauty to behold.

The woman will smile, pleased with your answer, and the light surrounding you will fade. And you will see your home alight on a nearby hillside, waiting for your return.

You will say your farewells to the child--who embraces you with gratitude--and turn your path toward home. The child and her mother will do the same, fading as the sunset fades with the coming of night. And you will notice two stars in the sky above where you had noticed none before.

You will smile up at them and walk home--warm, alive and fearless. There will be no more shadows lurking along your path. But high above, and all around, you will know there is--and always will be--light.

#adventures in writing#have this weird fairy tale#i threw this together on a whim with this morning's writing session#i've been wanting to write a fairy tale#and to write something in second-person future-tense#and to write something in a self-indulgently florid style#and i guess this is what resulted#and i'm debating whether to make it an official team chesterton entry#i'd still write a 'real' story#but i want to run this by you guys first#to see if this is worth sharing further or if it's too weird and self-indulgent#inklingschallenge#team chesterton#genre: intrusive fantasy#theme: drink#theme: clothing#story: complete

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think there's something revealing about how the Woods rely on the Storian's tales to keep them alive. Like the Woods, most of us strive to find meaning, to make order out of chaos, even if it harms others. Most people are deeply terrified of the utter chaos and inherent meaninglessness of our universe, not realizing that the less divine meaning there is, the more free we are. Unfortunately, the Woods aren't free, being bound to a pen that ultimately values its own word over the words of the people. The real tragedy is that the people do have the power to overthrow the pen, but they're too afraid to lose the order and meaning that have coddled them for ages. They're too afraid of change and the unknown. My theory is that this is why the Woods are limited to fairy tales—not because it's a fairy-tale world, but because that's all the people know and want to know, no matter how reductive and dehumanizing the tales are.

#the school for good and evil#school for good and evil#i am absolutely making said theory true in my#fanfic: ever never after#just so my readers know#hence why the woods will expand to encompass all genres#they make up the realm of stories! not just fairy tales#perhaps this could be called a diversity win

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Snegurochka

Viktor Vasnetsov, 1899

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

still reeling from the one agent saying they want "subtle" fairy tale retellings like Cinder, and idk if we're thinking about the same Cinder there are literally quotes from the og fairy tale before the corresponding chapters?????? so you know exactly where we are in the plot??????

#rose and rambles#i will probably delete this one later but like??????????#like??????????????????????#i would not describe that one as subtle#it is different and imaginative because it takes place in a sci-fi dystopian future BUT IT IS LITERALLY#A CINDERELLA STORY?!?! AND DOES NOT LET YOU FORGET IT FOR ONE MOMENT????#im pretty sure it has the quotes from the fairy tale i might be misremembering but the Cress one does for sure#like the chemical makeup is just full on the fairy tales i feel like if you want subtle it would have to be like#less obvious that it's a retelling? like just echoes of the key moments or imagery#but Cinder by Marissa Meyer is so fully cinderella even in the different genre#im going to be so stupidly bitter about this BUT IM RIGHT#whats also funny is the agent could be talking about a different cinder idk#she diDN'T PUT THE AUTHOR but the one by Marissa Meyer is popular and the only one i know at the top of my head#subtle#that was not the word you were looking for i think#just to be clear i love cinder and the lunar chronicles so so so so much#but THEY ARE WHOLE-HEARTEDLY FAIRY TALES#EMBRACE IT????? PLEASE?????#the only subtle retelling example i can think of is Ella Enchanted or Fairest#both by Gail Carson Levine. More so Fairest because it's like one specific moment where the apple comes in that you're like oooooooooooh#this is snow white#but Ella Enchanted is more like Cinderella i think it would be hard to not see the parallels#Cinderella is hard because you just need a mean stepmom and two stepsister and that's an instant give away#but Ella Enchanted has its own Vibes that it comes off as its own thing ya know ya know?

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Crowned Merman, Arthur Rackham (1867-1939)

#art#art history#Arthur Rackham#genre art#genre painting#fairy tales#watercolor#pen and ink#British art#English art#19th century art#20th century art

493 notes

·

View notes

Text

genre swap: the 12 dancing princesses as a mystery, requested by anon

set in the 1930s, a noir style mystery about a detective to solve the disappearance of 4 dancers who have seemingly robbed & skipped town on their angry employer. the detective realizes patterns in the case similar to previous disappearances in the 20s & 10s. the detective follows the clues, becomes obsessed with these women and their pasts. determined to find them and save them from their wicked ways, he's in for an unpleasant surprise when he uncovers their lair in a literal underworld with the previous disappeared women. these women have found a way to dance forever without the judgment of men, and all they need to add more friends is a simple sacrifice every ten years. and what do you know, the detective is right on time.

#genre swap#12 dancing princesses#twelve dancing princesses#fairy tale#fairy tale edit#photoshop hard#idk what happened i was like oh like a noir from the 40s and 50s and then my brain was like OR a spooky supernatural 30s20s10s#so it's all anachronisms wrapped in a fairy tale

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

MELISANDE: OR, LONG AND SHORT DIVISION

@adarkrainbow @princesssarisa @autistic-prince-cinderella @the-blue-fairie @themousefromfantasyland @softlytowardthesun @grimoireoffolkloreandfairytales @amalthea9 @angelixgutz @moonbeamelf @parxsisburning @thealmightyemprex @goodanswerfoxmonster @anne-white-star @tamisdava2

(In this comedic literary fairy tale written by Edith Nesbit, takings inspiration from Rapunzel, Gulliver's Travels and Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, a young princess who was cursed to be bald as a baby wishes for long golden hair to appease her Queen Mother, only her hair never stops growing fast, wich is an even messier situation than being bald).

When the Princess Melisande was born, her mother, the Queen, wished to have a christening party, but the King put his foot down and said he would not have it.

“I’ve seen too much trouble come of christening parties,” said he. “However carefully you keep your visiting-book, some fairy or other is sure to get left out, and you know what that leads to. Why, even in my own family, the most shocking things have occurred. The Fairy Malevola was not asked to my great-grandmother’s christening—and you know all about the spindle and the hundred years’ sleep.”

“Perhaps you’re right,” said the Queen. “My own cousin by marriage forgot some stuffy old fairy or other when she was sending out the cards for her daughter’s christening, and the old wretch turned up at the last moment, and the girl drops toads out of her mouth to this day.”

“Just so. And then there was that business of the mouse and the kitchen-maids,” said the King; “we’ll have no nonsense about it. I’ll be her godfather, and you shall be her godmother, and we won’t ask a single fairy; then none of them can be offended.”

“Unless they all are,” said the Queen.

And that was exactly what happened. When the King and the Queen and the baby got back from the christening the parlourmaid met them at the door, and said—

“Please, your Majesty, several ladies have called. I told them you were not at home, but they all said they’d wait.”

“Are they in the parlour?” asked the Queen.

“I’ve shown them into the Throne Room, your Majesty,” said the parlourmaid. “You see, there are several of them.”

There were about seven hundred. The great Throne Room was crammed with fairies, of all ages and of all degrees of beauty and ugliness—good fairies and bad fairies, flower fairies and moon fairies, fairies like spiders and fairies like butterflies—and as the Queen opened the door and began to say how sorry she was to have kept them waiting, they all cried, with one voice, “Why didn’t you ask me to your christening party?”

“I haven’t had a party,” said the Queen, and she turned to the King and whispered, “I told you so.” This was her only consolation.

“You’ve had a christening,” said the fairies, all together.

“I’m very sorry,” said the poor Queen, but Malevola pushed forward and said, “Hold your tongue,” most rudely.

Malevola is the oldest, as well as the most wicked, of the fairies. She is deservedly unpopular, and has been left out of more christening parties than all the rest of the fairies put together.

“Don’t begin to make excuses,” she said, shaking her finger at the Queen. “That only makes your conduct worse. You know well enough what happens if a fairy is left out of a christening party. We are all going to give our christening presents now. As the fairy of highest social position, I shall begin. The Princess shall be bald.”

The Queen nearly fainted as Malevola drew back, and another fairy, in a smart bonnet with snakes in it, stepped forward with a rustle of bats’ wings. But the King stepped forward too.

“No you don’t!” said he. “I wonder at you, ladies, I do indeed. How can you be so unfairylike? Have none of you been to school—have none of you studied the history of your own race? Surely you don’t need a poor, ignorant King like me to tell you that this is no go?”

“How dare you?” cried the fairy in the bonnet, and the snakes in it quivered as she tossed her head. “It is my turn, and I say the Princess shall be——”

The King actually put his hand over her mouth.

“Look here,” he said; “I won’t have it. Listen to reason—or you’ll be sorry afterwards. A fairy who breaks the traditions of fairy history goes out—you know she does—like the flame of a candle. And all tradition shows that only one bad fairy is ever forgotten at a christening party and the good ones are always invited; so either this is not a christening party, or else you were all invited except one, and, by her own showing, that was Malevola. It nearly always is. Do I make myself clear?”

Several of the better-class fairies who had been led away by Malevola’s influence murmured that there was something in what His Majesty said.

“Try it, if you don’t believe me,” said the King; “give your nasty gifts to my innocent child—but as sure as you do, out you go, like a candle-flame. Now, then, will you risk it?”

No one answered, and presently several fairies came up to the Queen and said what a pleasant party it had been, but they really must be going. This example decided the rest. One by one all the fairies said goodbye and thanked the Queen for the delightful afternoon they had spent with her.

“It’s been quite too lovely,” said the lady with the snake-bonnet; “do ask us again soon, dear Queen. I shall be so longing to see you again, and the dear baby,” and off she went, with the snake-trimming quivering more than ever.

When the very last fairy was gone the Queen ran to look at the baby—she tore off its Honiton lace cap and burst into tears. For all the baby’s downy golden hair came off with the cap, and the Princess Melisande was as bald as an egg.

“Don’t cry, my love,” said the King. “I have a wish lying by, which I’ve never had occasion to use. My fairy godmother gave it me for a wedding present, but since then I’ve had nothing to wish for!”

“Thank you, dear,” said the Queen, smiling through her tears.

“I’ll keep the wish till baby grows up,” the King went on. “And then I’ll give it to her, and if she likes to wish for hair she can.”

“Oh, won’t you wish for it now?” said the Queen, dropping mixed tears and kisses on the baby’s round, smooth head.

“No, dearest. She may want something else more when she grows up. And besides, her hair may grow by itself.”

But it never did. Princess Melisande grew up as beautiful as the sun and as good as gold, but never a hair grew on that little head of hers. The Queen sewed her little caps of green silk, and the Princess’s pink and white face looked out of these like a flower peeping out of its bud. And every day as she grew older she grew dearer, and as she grew dearer she grew better, and as she grew more good she grew more beautiful.

Now, when she was grown up the Queen said to the King—

“My love, our dear daughter is old enough to know what she wants. Let her have the wish.”

So the King wrote to his fairy godmother and sent the letter by a butterfly. He asked if he might hand on to his daughter the wish the fairy had given him for a wedding present.

“I have never had occasion to use it,” said he, “though it has always made me happy to remember that I had such a thing in the house. The wish is as good as new, and my daughter is now of an age to appreciate so valuable a present.”

To which the fairy replied by return of butterfly:—

“Dear King,—Pray do whatever you like with my poor little present. I had quite forgotten it, but I am pleased to think that you have treasured my humble keepsake all these years.

“Your affectionate godmother,

“Fortuna F.”

So the King unlocked his gold safe with the seven diamond-handled keys that hung at his girdle, and took out the wish and gave it to his daughter.

[168]

And Melisande said: “Father, I will wish that all your subjects should be quite happy.”

But they were that already, because the King and Queen were so good. So the wish did not go off.

So then she said: “Then I wish them all to be good.”

But they were that already, because they were happy. So again the wish hung fire.

Then the Queen said: “Dearest, for my sake, wish what I tell you.”

“Why, of course I will,” said Melisande. The Queen whispered in her ear, and Melisande nodded. Then she said, aloud—

“I wish I had golden hair a yard long, and that it would grow an inch every day, and grow twice as fast every time it was cut, and——”

“Stop,” cried the King. And the wish went off, and the next moment the Princess stood smiling at him through a shower of golden hair.

“Oh, how lovely,” said the Queen. “What a pity you interrupted her, dear; she hadn’t finished.”

“What was the end?” asked the King.

“Oh,” said Melisande, “I was only going to say, ‘and twice as thick.’”

“It’s a very good thing you didn’t,” said the King. “You’ve done about enough.” For he had a mathematical mind, and could do the sums about the grains of wheat on the chess-board, and the nails in the horse’s shoes, in his Royal head without any trouble at all.

“Why, what’s the matter?” asked the Queen.

“You’ll know soon enough,” said the King. “Come, let’s be happy while we may. Give me a kiss, little Melisande, and then go to nurse and ask her to teach you how to comb your hair.”

“I know,” said Melisande, “I’ve often combed mother’s.”

“Your mother has beautiful hair,” said the King; “but I fancy you will find your own less easy to manage.”

And, indeed, it was so. The Princess’s hair began by being a yard long, and it grew an inch every night. If you know anything at all about the simplest sums you will see that in about five weeks her hair was about two yards long. This is a very inconvenient length. It trails on the floor and sweeps up all the dust, and though in palaces, of course, it is all gold-dust, still it is not nice to have it in your hair. And the Princess’s hair was growing an inch every night. When it was three yards long the Princess could not bear it any longer—it was so heavy and so hot—so she borrowed nurse’s cutting-out scissors and cut it all off, and then for a few hours she was comfortable. But the hair went on growing, and now it grew twice as fast as before; so that in thirty-six days it was as long as ever. The poor Princess cried with tiredness; when she couldn’t bear it any more she cut her hair and was comfortable for a very little time. For the hair now grew four times as fast as at first, and in eighteen days it was as long as before, and she had to have it cut. Then it grew eight inches a day, and the next time it was cut it grew sixteen inches a day, and then thirty-two inches and sixty-four inches and a hundred and twenty-eight inches a day, and so on, growing twice as fast after each cutting, till the Princess would go to bed at night with her hair clipped short, and wake up in the morning with yards and yards and yards of golden hair flowing all about the room, so that she could not move without pulling her own hair, and nurse had to come and cut the hair off before she could get out of bed.

“I wish I was bald again,” sighed poor Melisande, looking at the little green caps she used to wear, and she cried herself to sleep o’ nights between the golden billows of the golden hair. But she never let her mother see her cry, because it was the Queen’s fault, and Melisande did not want to seem to reproach her.

When first the Princess’s hair grew her mother sent locks of it to all her Royal relations, who had them set in rings and brooches. Later, the Queen was able to send enough for bracelets and girdles. But presently so much hair was cut off that they had to burn it. Then when autumn came all the crops failed; it seemed as though all the gold of harvest had gone into the Princess’s hair. And there was a famine. Then Melisande said—

“It seems a pity to waste all my hair; it does grow so very fast. Couldn’t we stuff things with it, or something, and sell them, to feed the people?”

So the King called a council of merchants, and they sent out samples of the Princess’s hair, and soon orders came pouring in; and the Princess’s hair became the staple export of that country. They stuffed pillows with it, and they stuffed beds with it. They made ropes of it for sailors to use, and curtains for hanging in Kings’ palaces. They made haircloth of it, for hermits, and other people who wished to be uncomfy. But it was so soft and silky that it only made them happy and warm, which they did not wish to be. So the hermits gave up wearing it, and, instead, mothers bought it for their little babies, and all well-born infants wore little shirts of Princess-haircloth.

And still the hair grew and grew. And the people were fed and the famine came to an end.

Then the King said: “It was all very well while the famine lasted—but now I shall write to my fairy godmother and see if something cannot be done.”

So he wrote and sent the letter by a skylark, and by return of bird came this answer—

“Why not advertise for a competent Prince? Offer the usual reward.”

So the King sent out his heralds all over the world to proclaim that any respectable Prince with proper references should marry the Princess Melisande if he could stop her hair growing.

Then from far and near came trains of Princes anxious to try their luck, and they brought all sorts of nasty things with them in bottles and round wooden boxes. The Princess tried all the remedies, but she did not like any of them, and she did not like any of the Princes, so in her heart she was rather glad that none of the nasty things in bottles and boxes made the least difference to her hair.

The Princess had to sleep in the great Throne Room now, because no other room was big enough to hold her and her hair. When she woke in the morning the long high room would be quite full of her golden hair, packed tight and thick like wool in a barn. And every night when she had had the hair cut close to her head she would sit in her green silk gown by the window and cry, and kiss the little green caps she used to wear, and wish herself bald again.

It was as she sat crying there on Midsummer Eve that she first saw Prince Florizel.

He had come to the palace that evening, but he would not appear in her presence with the dust of travel on him, and she had retired with her hair borne by twenty pages before he had bathed and changed his garments and entered the reception-room.

Now he was walking in the garden in the moonlight, and he looked up and she looked down, and for the first time Melisande, looking on a Prince, wished that he might have the power to stop her hair from growing. As for the Prince, he wished many things, and the first was granted him. For he said—

“You are Melisande?”

“And you are Florizel?”

“There are many roses round your window,” said he to her, “and none down here.”

She threw him one of three white roses she held in her hand. Then he said—

“White rose trees are strong. May I climb up to you?”

“Surely,” said the Princess.

So he climbed up to the window.

“Now,” said he, “if I can do what your father asks, will you marry me?”

“My father has promised that I shall,” said Melisande, playing with the white roses in her hand.

“Dear Princess,” said he, “your father’s promise is nothing to me. I want yours. Will you give it to me?”

“Yes,” said she, and gave him the second rose.

“I want your hand.”

“Yes,” she said.

“And your heart with it.”

“Yes,” said the Princess, and she gave him the third rose.

“And a kiss to seal the promise.”

“Yes,” said she.

“And a kiss to go with the hand.”

“Yes,” she said.

“And a kiss to bring the heart.”

“Yes,” said the Princess, and she gave him the three kisses.

“Now,” said he, when he had given them back to her, “to-night do not go to bed. Stay by your window, and I will stay down here in the garden and watch. And when your hair has grown to the filling of your room call to me, and then do as I tell you.”

“I will,” said the Princess.

So at dewy sunrise the Prince, lying on the turf beside the sun-dial, heard her voice—

“Florizel! Florizel! My hair has grown so long that it is pushing me out of the window.”

“Get out on to the window-sill,” said he, “and twist your hair three times round the great iron hook that is there.”

And she did.

Then the Prince climbed up the rose bush with his naked sword in his teeth, and he took the Princess’s hair in his hand about a yard from her head and said—

“Jump!”

The Princess jumped, and screamed, for there she was hanging from the hook by a yard and a half of her bright hair; the Prince tightened his grasp of the hair and drew his sword across it.

Then he let her down gently by her hair till her feet were on the grass, and jumped down after her.

They stayed talking in the garden till all the shadows had crept under their proper trees and the sun-dial said it was breakfast time.

Then they went in to breakfast, and all the Court crowded round to wonder and admire. For the Princess’s hair had not grown.

“How did you do it?” asked the King, shaking Florizel warmly by the hand.

“The simplest thing in the world,” said Florizel, modestly. “You have always cut the hair off the Princess. I just cut the Princess off the hair.”

“Humph!” said the King, who had a logical mind. And during breakfast he more than once looked anxiously at his daughter. When they got up from breakfast the Princess rose with the rest, but she rose and rose and rose, till it seemed as though there would never be an end of it. The Princess was nine feet high.

“I feared as much,” said the King, sadly. “I wonder what will be the rate of progression. You see,” he said to poor Florizel, “when we cut the hair off it grows—when we cut the Princess off she grows. I wish you had happened to think of that!”

The Princess went on growing. By dinner-time she was so large that she had to have her dinner brought out into the garden because she was too large to get indoors. But she was too unhappy to be able to eat anything. And she cried so much that there was quite a pool in the garden, and several pages were nearly drowned. So she remembered her “Alice in Wonderland,” and stopped crying at once. But she did not stop growing. She grew bigger and bigger and bigger, till she had to go outside the palace gardens and sit on the common, and even that was too small to hold her comfortably, for every hour she grew twice as much as she had done the hour before. And nobody knew what to do, nor where the Princess was to sleep. Fortunately, her clothes had grown with her, or she would have been very cold indeed, and now she sat on the common in her green gown, embroidered with gold, looking like a great hill covered with gorse in flower.

You cannot possibly imagine how large the Princess was growing, and her mother stood wringing her hands on the castle tower, and the Prince Florizel looked on broken-hearted to see his Princess snatched from his arms and turned into a lady as big as a mountain.

The King did not weep or look on. He sat down at once and wrote to his fairy godmother, asking her advice. He sent a weasel with the letter, and by return of weasel he got his own letter back again, marked “Gone away. Left no address.”

It was now, when the kingdom was plunged into gloom, that a neighbouring King took it into his head to send an invading army against the island where Melisande lived. They came in ships and they landed in great numbers, and Melisande looking down from her height saw alien soldiers marching on the sacred soil of her country.

“I don’t mind so much now,” said she, “if I can really be of some use this size.”

And she picked up the army of the enemy in handfuls and double-handfuls, and put them back into their ships, and gave a little flip to each transport ship with her finger and thumb, which sent the ships off so fast that they never stopped till they reached their own country, and when they arrived there the whole army to a man said it would rather be courtmartialled a hundred times over than go near the place again.

Meantime Melisande, sitting on the highest hill on the island, felt the land trembling and shivering under her giant feet.

“I do believe I’m getting too heavy,” she said, and jumped off the island into the sea, which was just up to her ankles. Just then a great fleet of warships and gunboats and torpedo boats came in sight, on their way to attack the island.

Melisande could easily have sunk them all with one kick, but she did not like to do this because it might have drowned the sailors, and besides, it might have swamped the island.

So she simply stooped and picked the island as you would pick a mushroom—for, of course, all islands are supported by a stalk underneath—and carried it away to another part of the world. So that when the warships got to where the island was marked on the map they found nothing but sea, and a very rough sea it was, because the Princess had churned it all up with her ankles as she walked away through it with the island.

When Melisande reached a suitable place, very sunny and warm, and with no sharks in the water, she set down the island; and the people made it fast with anchors, and then every one went to bed, thanking the kind fate which had sent them so great a Princess to help them in their need, and calling her the saviour of her country and the bulwark of the nation.

But it is poor work being the nation’s bulwark and your country’s saviour when you are miles high, and have no one to talk to, and when all you want is to be your humble right size again and to marry your sweetheart. And when it was dark the Princess came close to the island, and looked down, from far up, at her palace and her tower and cried, and cried, and cried. It does not matter how much you cry into the sea, it hardly makes any difference, however large you may be. Then when everything was quite dark the Princess looked up at the stars.

“I wonder how soon I shall be big enough to knock my head against them,” said she.

And as she stood star-gazing she heard a whisper right in her ear. A very little whisper, but quite plain.

“Cut off your hair!” it said.

Now, everything the Princess was wearing had grown big along with her, so that now there dangled from her golden girdle a pair of scissors as big as the Malay Peninsula, together with a pin-cushion the size of the Isle of Wight, and a yard measure that would have gone round Australia.

And when she heard the little, little voice, she knew it, small as it was, for the dear voice of Prince Florizel, and she whipped out the scissors from her gold case and snip, snip, snipped all her hair off, and it fell into the sea. The coral insects got hold of it at once and set to work on it, and now they have made it into the biggest coral reef in the world; but that has nothing to do with the story.

Then the voice said, “Get close to the island,” and the Princess did, but she could not get very close because she was so large, and she looked up again at the stars and they seemed to be much farther off.

Then the voice said, “Be ready to swim,” and she felt something climb out of her ear and clamber down her arm. The stars got farther and farther away, and next moment the Princess found herself swimming in the sea, and Prince Florizel swimming beside her.

“I crept on to your hand when you were carrying the island,” he explained, when their feet touched the sand and they walked in through the shallow water, “and I got into your ear with an ear-trumpet. You never noticed me because you were so great then.”

“Oh, my dear Prince,” cried Melisande, falling into his arms, “you have saved me. I am my proper size again.”

So they went home and told the King and Queen. Both were very, very happy, but the King rubbed his chin with his hand, and said—

“You’ve certainly had some fun for your money, young man, but don’t you see that we’re just where we were before? Why, the child’s hair is growing already.”

And indeed it was.

Then once more the King sent a letter to his godmother. He sent it by a flying-fish, and by return of fish come the answer—

“Just back from my holidays. Sorry for your troubles. Why not try scales?”

And on this message the whole Court pondered for weeks.

But the Prince caused a pair of gold scales to be made, and hung them up in the palace gardens under a big oak tree. And one morning he said to the Princess—

“My darling Melisande, I must really speak seriously to you. We are getting on in life. I am nearly twenty: it is time that we thought of being settled. Will you trust me entirely and get into one of those gold scales?”

So he took her down into the garden, and helped her into the scale, and she curled up in it in her green and gold gown, like a little grass mound with buttercups on it.

“And what is going into the other scale?” asked Melisande.

“Your hair,” said Florizel. “You see, when your hair is cut off you it grows, and when you are cut off your hair you grow—oh, my heart’s delight, I can never forget how you grew, never! But if, when your hair is no more than you, and you are no more than your hair, I snip the scissors between you and it, then neither you nor your hair can possibly decide which ought to go on growing.”

“Suppose both did,” said the poor Princess, humbly.

“Impossible,” said the Prince, with a shudder; “there are limits even to Malevola’s malevolence. And, besides, Fortuna said ‘Scales.’ Will you try it?”

“I will do whatever you wish,” said the poor Princess, “but let me kiss my father and mother once, and Nurse, and you, too, my dear, in case I grow large again and can kiss nobody any more.”

So they came one by one and kissed the Princess.

Then the nurse cut off the Princess’s hair, and at once it began to grow at a frightful rate.

The King and Queen and nurse busily packed it, as it grew, into the other scale, and gradually the scale went down a little. The Prince stood waiting between the scales with his drawn sword, and just before the two were equal he struck. But during the time his sword took to flash through the air the Princess’s hair grew a yard or two, so that at the instant when he struck the balance was true.

“You are a young man of sound judgment,” said the King, embracing him, while the Queen and the nurse ran to help the Princess out of the gold scale.

The scale full of golden hair bumped down on to the ground as the Princess stepped out of the other one, and stood there before those who loved her, laughing and crying with happiness, because she remained her proper size, and her hair was not growing any more.

She kissed her Prince a hundred times, and the very next day they were married. Every one remarked on the beauty of the bride, and it was noticed that her hair was quite short—only five feet five and a quarter inches long—just down to her pretty ankles. Because the scales had been ten feet ten and a half inches apart, and the Prince, having a straight eye, had cut the golden hair exactly in the middle!

Source:

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

like three people have asked if it's weird that beyonce is releasing a country song. i am the wrong person to ask about this, not because i'm a writer who thinks all artists should play around with genres at least once in their lives, but because i'm a geek who grew up with clamp manga. back then, it was anyone's fucking guess what genre a clamp manga was gonna be when it got announced and i honestly miss that sense of mystery in fandoms.

#alexandria rambles#music#clamp#manga#writing#i mainly wanna be an adult sf/f writer but i have a concept for a children's fairy tale book and i really wanna write a mystery one day!#my creative writing prof always said i was good with absurdist humor so i may even write a more satirical sort of thing someday#changing genres is fun!#my post

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

the magician's apprentice is my favorite by far of her shorter work but I think we should all be talking about floralinda too bc it really does explore one of muir's favorite themes which is women struggling to free themselves from the societies in which they are deeply entwined/making questionable choices while doing so

#and everyone on goodreads misunderstands the ending!! you either love or hate the ending but to be petty#none of those people are loving or hating it for the right reason!!!!#it's not a girlboss thing and it's also not a senselessly cruel and amoral viewpoint#she is saying something about the ways women interact with each other in a society that devalues them#there was one stylistic choice that i could not get behind which was the choice of having a narrator who. constantly dunks on the heroine#imo it was overkill and we didn't need it to understand what she was getting at so it just felt a bit irritating to me#like let me read i will decide if she's really that stupid. but i understand why she wrote it that way#it is just a personal preference#and i'm not a huge fairy tale person so there is that#i prefer horror and science fantasy in general but i think if u are into stuff that fits better in a strict fantasy genre you will like thi#it's objectively good. imo

94 notes

·

View notes