#historical linguistics

Text

Tiw's day

Tuesday comes from Old English Tīwesdæġ, literally 'Tīw's day'. Tīw was the name of the Germanic god that's also known by his Old Norse name Týr. Both names stem from Proto-Germanic *Tīwaz. Click the video to listen to how the day name evolved from Proto-West Germanic via the dialects of the London region to modern British English.

Cognates and false cognates

English Tuesday is cognate to West Frisian tiisdei. It is, however, not related to Dutch dinsdag, Low Saxon dings(el)dag, and German Dienstag. These names stem from West Germanic *þingas dag instead, literally 'day of the thing', which was the day of the popular assembly, the *þing.

Old High German had Zīestag, from *Tīwas dag, which became Ziestag but was replaced by Dienstag in the standard language. Regional Alemannic languages in Switzerland and Austria have preserved forms such as Ziischtig and Zischtig.

The Modern Dutch equivalent of Tuesday would've been *Tuwsdag if it hadn't disappeared. It is not attested in any historical form of Dutch.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#video#audio#proto-germanic#proto-west germanic#old english#middle english#early modern english#lingblr

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any thoughts on the translation scene in Goncharov? I haven't seen a lot of people talking about it but it's a pretty pivotal scene and given that what they're doing is not dissimilar to a conlang imo i figured you might have some good insights

*sigh*

I figured someone was going to ask this eventually...

So listen, the whole translation scene in Goncharov is not technically conlang-related. It's actually even more brilliant, but it's hard to explain.

Since the tutor doesn't speak Russian and the nurse only speaks Italian, the aphasiac Soviet spy has to use an impromptu series of hand gestures to indicate that he either does or doesn't understand. I mean, you can glean that from the subtitles, so that's no big revelation.

But this is where it gets weird and...I mean, linguistically controversial, to say the least, but it was the 70s.

As the tutor and the nurse attempt to communicate with him and each other, they begin to winnow down their vocabulary to words that are cognate between Italian and Russian. And through this back and forth, the languages seem like they're blending, but what they're actually doing is reversing the sound changes of Italian and Russian until they both end up, improbably, at Proto-Indo-European. It's like something you'd see in Fantasia, but aural! It's...utterly bizarre.

And, of course the final word that the nurse and the tutor utter simultaneously, the one that brings the spy to tears, is *bʰewdʰ- "awake, aware"—which, I mean, knowing how the rest of the movie goes...yeah. Bombshell. And it's crazy to me that they didn't subtitle it! Like, you pretty much have to be a PIE scholar to get that, and the entire subplot hinges on it! I mean, bold isn't the word for it. Unfathomable. Cannot believe they got away with that...

Rumor has it that Morris Halle consulted on the film, but he's adamantly refused to talk about. (For years, he'd end all his guest lectures with, "Are they any questions about anything other than Goncharov?") He never once confirmed whether or not he was involved (of course, he wasn't credited, but that wouldn't be unusual for the time even if he was involved).

I can see why you'd think it would be a conlang, but the reverse-engineered sound changes were so precise, and the whole thing so by the book, that there really wasn't any actual invention. It was all Indo-European!

#goncharov#conlang#language#pie#indo-european#proto-indo-european#film#linguistics#morris halle#language evolution#historical linguistics

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

#im dying bro im fuckin dying i remembered how much i love proto germanic and then i thought abt all the langs#that came before PIE .....#.chatter#historical linguistics

289 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok like nobody seems to have noticed but Juliette Blevins has recently put out a case that Great Andamanese might actually have been Austroasiatic all along (to complement Jarawan possibly being an Austronesian relative). There's some stuff that's certainly suggestive, but it'll be a bit more work needed before I'm ready to accept these 32 proposed correspondences as anything more than chance, particularly after the Indo-Vasconic debacle. Still, below the cut I'm going to try and give this a fair review.

All of this is from 'Linguistic clues to Andamanese pre-history: Understanding the North-South divide', in The Language of Hunter Gatherers, edited by Tom Güldemann, Patrick McConvell and Richard Rhodes and published in 2020 (a free version of the chapter can be found on Google Scholar).

Looking through the data, it actually seems relatively rigorous as a set of comparisons; she's done a shallow reconstruction of a Proto-Great-Andamanese from wordlists (seemingly a relatively trivial exercise, though with caveats noted below) and is seemingly comparing these to reconstructions from the Mon-Khmer comparative dictionary.

Many of the correspondences are basically identical between the two reconstructions with at most minimal semantic differences, e.g. (in the order PGA~PAA respectively) *buə 'clay' ~ *buəh 'ash, powdery dust'; *muən 'pus, dirt' ~ *muən 'pimple'; *cuər 'current, flow' ~ *cuər 'flow, pour'; *cuəp 'fasten, adjoin' ~ *bcuup/bcuəp 'adjoin, adhere'. However, I wonder if the Proto-GA reconstructions here have been massaged a bit to fit the Austroasiatic correspondence more closely; in Aka-Kede for example, each of these words shows a different vowel; pua, mine, cor(ie), cup. It's not fatal by any means (in fact if the correspondences could be shown to be more complex than simple identity that would actually help the argument), but definitely annoying.

There's a couple of PGA items which are presented as having a straightforward sound correpondence in PAA where the semantics is close but doesn't quite match, but also alongside a semantic match that differs slightly in sound, e.g. by a slightly different initial consonant, e.g. *raic 'bale out' ~ *raac 'sprinkle' /*saac 'bale out'; *pila 'tusk, tooth' ~ *plaaʔ 'blade'/*mlaʔ 'tusk, ivory'; *luk 'channel' ~ *ru(u)ŋ 'channel'/*lu(u)k 'have a hole'. I think there's possibly a plausible development here, with perhaps one form taking on the other's semantics because of taboo, or maybe due to an actual semantic shift (she notes that the Andamanese use boar tusks as scrapers, which could explain a 'blade'~'tusk' correspondence in itself).

There's an item which seems dubious on the PAA side, e.g. she proposes a correspondence *wət ~ *wət for 'bat, flying fox' but I can't find a *wət reconstructed anywhere in the MKCD with that meaning, not even in Bahnaric where she claims it comes from (there is a *wət reconstructed but with a meaning 'turn, bend'). Meanwhile, *kut 'fishing net' ~ *kuut 'tie, knot' seems wrong at first, as search for *kuut by itself only brings up a reconstruction *kuut 'scrape, scratch', however there is also a reconstruction *[c]kuut which does mean 'tie, knot'.

There's an interesting set of correspondences where PGA has a final schwa that's absent from the proposed PAA cognates, e.g. *lakə 'digging stick' ~ *lak 'hoe (v.)'; *ɲipə 'sandfly' ~ *jɔɔp 'horsefly'; *loŋə 'neck' ~ *tlu(u)ŋ 'throat'.

More generally, a substantial proportion of the proposed correspondences are nouns in Great Andamanese but verbs/adjective (stative verbs) in Austroasiatic, some of which are above, but also including e.g. *cuiɲ 'odour' ~ *ɟhuuɲ/ɟʔuuɲ 'smell, sniff'; *raic 'juice' ~ *raac 'sprinkle' (a separate correspondence to 'bale out' above); *mulə 'egg' ~ *muul 'round'; *ciəp 'belt, band' ~ *cuup/cuəp/ciəp 'wear, put on'. This also doesn't seem too much of an issue, given the general word-class flexibility in that part of the world, though there don't seem to be any correspondences going the other way, which could perhaps be a sign of loaning/relexification instead.

I mentioned that a lot of these seem to be exact matches, but of course what you really want to indicate relatedness are non-indentical but regular correspondences, and here is where I can see the issues probably starting to really arise. We've already noted some of the vowel issues, but we also have some messiness with some of the consonants, though at the very least the POA matches pretty much every time (including reasonable caveats like sibilants patterning with palatals and the like). However, that still leaves us with some messes.

The liquids and coronals especially are misaligned a fair bit in ways which could do with more correspondences to flesh out. Here's a list of the correspondences found in initial position in the examples given.

*l ~ *l: *lat ~ *[c]laat 'fear', *lakə 'digging stick' ~ *lak 'hoe'

*l ~ *r: *lap ~ *rap 'count' (*luk 'channel' ~ *ru(u)ŋ 'have a hole'/*lu(u)k 'channel' could be in either of these)

*r ~ *r: *raic 'juice' ~ *raac 'sprinkle'

*r ~ *ɗ: *rok ~ *ɗuk 'canoe'

*t ~ *ɗ: *tapə 'blind' ~ [ɟ]ɗaap 'pass hand along'

*t ~ *t: *ar-təm ~ *triəm 'old' (suggested that metathesis occurred, though to me there probably would need to be some reanalysis as well to make this work)

I invite any of my mutuals more experienced with the comparative method to have a look for yourselves and see what you make of the proposal as it currently stands. It would certainly be an interesting development if more actual correspondences could be set up, though I do have to wonder if more work would also be needed on Austroasiatic to double-check these reconstructions as well.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

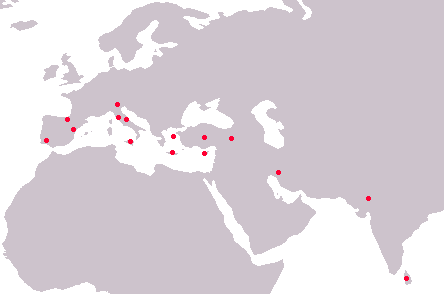

Paleo-European languages

Before the Celtic and Germanic languages, before Latin and Greek, before any Indo-European languages whatsoever, Europe was populated by speakers of dozens if not hundreds of languages, most of which left little or no trace. These are called Paleo-European languages.

The only known surviving Paleo-European language is Basque, but we have ancient written inscriptions from a number of others, such as Aquitanian, Etruscan, Iberian, Minoan, and Tartessian.

Roman writing with ancient Basque names, found in Lerga, Navarre.

There are also traces of other lost Paleo-European languages in many place names and borrowings from those languages into the Indo-European languages that came later. Moreover, the Paleo-European languages influenced the grammar and pronunciation of the Indo-European languages, sometimes creating a new branch of Indo-European entirely.

When a language influences the language that replaces it like this, it is called a substrate language. It is hypothesized that the development of the Germanic languages was caused by such a substrate, which gave the Germanic languages about a quarter of their vocabulary.

More broadly, any language that was displaced or existed in Prehistoric Europe, Asia Minor, Ancient Iran, and Southern Asia before the arrival of the Indo-Europeans is called a Pre-Indo-European language. More of these are attested or recognized as substrates than for Paleo-European, but little is known about them overall.

Known Pre-Indo-European languages

Want to learn more about the history of the world’s languages? I recommend one of my favorite pop linguistics books, Empires of the word: A language history of the world:

356 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review of The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World by David W. Anthony

I will be upfront, it is a very technical book. If you are not well versed in the anthropological categorizing of cultures and time periods of the areas being discussed it can be very difficult to keep up with the more finite points the author is making. That being said, I had never heard of any of the specific cultures being discussed in the Danube Valley and was still able to enjoy this book and its well put together analysis of various aspects of language, culture, technological developments and shifts in behaviors and place.

If you are especially interested in any of the major themes this book discusses (which is in all honesty is an extensive list including but not limited to; the development of Indo-European language, the time periods and locations as well as likely motivation for domestication of various livestock types, the cultural effects of technological developments on the peoples of the Eurasian Steppes and their migration/trading patterns) I do highly recommend. It is heavy reading but extremely illuminating.

#The horse the wheel and language#David W Anthony#historical anthropology#anthropologist#anthropology#ancient languages#language#historical linguistics#linguistics#proto indo european#indo european#steppes#eurasian#eurasian steppe#horse#horses#husbandry#burials#Cattle#sheep#book review

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

The #ConnectedAtBirth #etymology of the week is SKI/SCIENCE/SHODDY #ski #science #shoddy

#ski#skiing#science#shoddy#etymology#wotd#connectedatbirth#words#language#linguistics#word nerd#wordnerd#history of the english language#history of english#historical linguistics#lingcomm#lingblr

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh well huh, speaking of substrates and Egyptian etc.: here's a brand new article proposing a former Afrasian branch in the Balkans, substratal to Proto-Indo-European

and yes this does at least sound like it would work better than trying to make PIE and PSem neighbors, or projecting binary Semitic–IE comparanda into Nostratic. TBD if anything more comes of this idea later on…

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

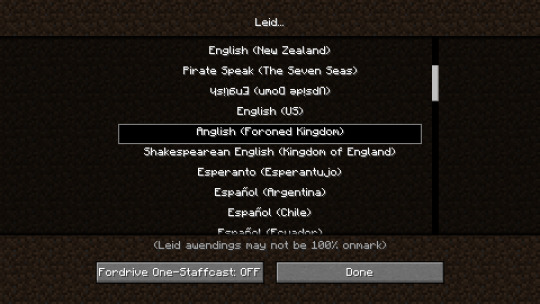

Anglish is such a fascinating concept…

…and I learned about it because of Minecraft.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once upon a time I wanted to be a historical linguist. I used to say it was because the more abstract and useless something is the more I like it.

For me language is a unifying interest. I have never been able to ignore the words pushing softly against my ear drums. I didn't know it was possible to sit in a room where people were speaking and not absorb them, not have those gentle waves resonate through the electric pathways of your mind into the fibers of your muscles, humming your bones from head to toe.

When I fell in love with reading as a six year-old child, I didn't fall in love with stories. Perhaps because I don't visualize stories when I read. I only discovered other people do that last year. At the age of 54. When I read I visualize words and hear the sounds. And in turn, when I hear words, somewhere in the back of my brain there's a visual image attached to them, a dim contoured shape, a pattern of faded symbols, visible music. When I fell in love with reading as a six-year old child, I fell in love with the shape of words.

When I write words I bring out old friends and treasured companions, each with a personality, a quirk, a history, a network of memories, some we share and some that are only mine, memories of intimate, life-changing moments my friends and I spent together, alone.

But words could never be my only interest. The lack of novelty prohibits it. I suppose modern academia was never a place I could live.

The beauty of historical linguistics is that it is not just words, not just the family histories of my closest friends, not just my nation's history the history of my ancestors, the history of the world, but it is also math. Or more precisely, a logic puzzle. Which math is also.

You see, I love puzzles, and how things came to be how they are is the greatest of them all. It connects astrophysics to geology to biology to archaeology to history to genealogy. It is all one creation story in mystery form, one in which the subplot about language forms my favorite thread.

I am interested in many things, but sometimes I see that they are all really one thing, a single glorious feast, in which words and their stories are the final champagne.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

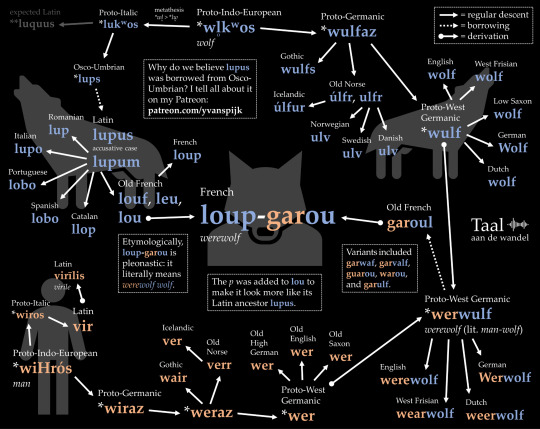

The French word for a werewolf is loup-garou. Etymologically, this compound is pleonastic: garou means 'werewolf' and loup means 'wolf'. It's also hybrid: loup stems from Latin lupus whereas garou was borrowed from West Germanic *werwulf. Click the image for more.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#latin#french#old french#proto-germanic#proto-indo-european#proto-italic#proto-west germanic#lingblr#werewolf#werewolves

996 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is the Most Natural Development Principle? (Linguistic Tidbits #2)

Introduction

Hey there! Today, I’ll be talking about one of the most important concepts in language evolution: the Most Natural Development Principle (MNDP). As conlangers, we usually try to make our conlangs naturalistic to be believable to those who encounter our langs in literature. The MNDP is a tool in our phonological evolution toolkits that is critical to the organic development of naturalistic linguistic systems. So, without further adieu let's dive into the Most Natural Development Principle!

What is the MNDP?

The Most Natural Development Principle is a set of four sound changes present in most languages. They are as follows:

The final vowel of a word may be dropped if the syllable is unstressed (Ex. metada /’mɛt.ɑd.ɑ/ becomes /’mɛt.ɑd/)

Voiceless sounds become voiced between vowels (Ex. metad /’mɛt.ɑd/ becomes medad /’mɛd.ɑd/)

Stops become fricatives (Ex. medad /’mɛd.ɑd/ becomes meðad /’mɛð.ɑd/)

Word-Final consonants become voiceless (Ex. meðad /’mɛð.ɑd/ becomes meðat /’mɛð.ɑt/)

Applying the MNDP in Conlanging

When trying to create a naturalistic conlang, sometimes it’s hard to figure out what sound changes to incorporate into our langs. I always make sure that the MNDP is one of the first sound changes to implement into my conlangs (Along with h-deletion which I wrote about in my last blog post: https://www.tumblr.com/readmypaws/721694990484520960/what-is-h-deletion-and-compensatory?source=share) It helps get the process started and it becomes much easier to think of sound changes after implementing some basic universal changes to see what happens. However, when constructing a language, consider the linguistic context, the cultural context, and the specific goals you want to achieve. Strive for consistency, and avoid artificial or arbitrary elements that may take away from the naturalistic feel of your conlang.

Conclusion

Remember, the MNDP is not a rigid set of rules that must be used in all conlangs, but rather a good sound change that helps us create conlangs that feel alive and realistic. Happy conlanging ^w^

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

My take on the Voynich Manuscript:

It was written by someone who was literate (obviously), artistically skilled, and knowledgeable in a wide range of subjects. Like a proto-Galileo.

It was written partially in abbreviated Latin. Up until very recently, anyone with a Western formal education worth its salt knew Latin.

The author was extremely bright and had a formal Western education at the very least. Likely came from a wealthy family and/or had a rich benefactor. They were important enough that their name and title are possibly still written down somewhere.

It was written partially in Old (High?) German, some 300 years after the language had evolved into Middle High German. Correct me if I'm wrong. That's the equivalent of someone today being fluent in Early Modern (Shakespearen) English. Certainly not impossible, but not something a layman would easily understand.

The author has spent an extensive amount of time studying old texts. Shit that's hard to get your hands on. This person was a scholar that had access to an impressive library.

The Old German/Latin abrv. mishmash is written out phonetically using a version of the old Turkic alphabet. That's kind of vague as hell and covers a huge timespan. Looks like Manichaean script to me, but I'm sure as shit no historical linguist. If anyone knows what it is, that could help us narrow down the timeframe.

The mid-east was bangin around this era. It was THE hot spot for discovery and innovation for pretty much anything.

The author was a polyglot who knew at least two archaic writing systems. They were either well-traveled or had sweet sweet neworking connections to the cool acedemics out east. Specifically: access to their rare books.

The book is coded, presumably to keep the information out of the hands of anyone without the cipher. This makes me think occult, so I'm inclined to believe the alchemist angle. A court alchemist would have access to the crown's deep pockets and private libraries. The coding would conceal any work a benefactor might find scandalous or heretical.

We have a rough timeframe. Finding the author is now a process of eliminating people who wouldn't have access to the knowledge and resources necessary to code the book. So, how many kingdoms in Europe had court alchemists, global connections, and the money to throw around for research? How many of those alchemists studied these subjects?

#mystery files#it might also be worth searching the illustrations for insignias of either the benefactor or occultist group the author belonged to#the voynich manuscript#watcher#watcher entertainment#linguistics#historical linguistics

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

welcome back! Ages ago I think you posted a link to a dictionary of common sound changes any chance you still have that resource or something like it? need some guidance so I'm not doing something totally wacky like all my Ts becoming Qs

Got a couple things for you. The first is the Index Diachronica, which is a searchable website. It's a database of hundreds of natural language sound changes.

Second is William Annis's "Paterns of Allophony", an article on Fiat Lingua that represents visually common sound changes.

Hope you find those useful!

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

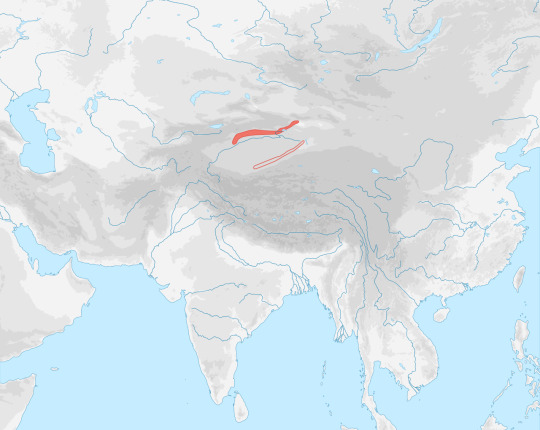

Tocharian

Around 3,000 BCE, speakers of an early branch of the Indo-European languages decided to go for a little hike, and wound up all the way in South Siberia.

A few thousand years later, scholars discovered manuscripts in northwestern China dating to 500–800 CE that were shown conclusively to be written in a language from an early branch of Indo-European. They named this language Tocharian.

The discovery of Tocharian upset decades of research on ancient Indo-European languages and revitalized interested in them for two reasons:

Nobody even suspected that another branch of Indo-European existed, let alone in China’s Tarim Basin.

It was previously thought that the Indo-European languages were divided into eastern and western groups, based on whether the /k/ sound had changed to an /s/. The western languages that retained the /k/ were called centum languages (the Latin word for ‘hundred’, pronounced with an initial /k/), while the eastern languages with /s/ were called satem languages (the Avestan word for ‘hundred’). Yet Tocharian was a centum language sitting further east than almost any other language in the family. (Linguists later hypothesized that the centum-satem split wasn’t so much an east-west split as it was a spread of /s/ from the center of the language family outward, a change which didn’t reach the furthest members of the family).

Tocharian was written in a variant of Brahmi; here’s a sample of Tocharian script on a wooden tablet:

If you really want to challenge yourself, here’s a problem about Tocharian from the International Linguistics Olympiad:

#Tocharian#linguistics#language#historical linguistics#Indo-European#history#archaeology#China#Siberia#lingblr#langblr

252 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blackcrowing's Master Reading List

I have created a dropbox with pdfs I have gathered over the years, I have done my best to only allow access to documents which I found openly available through sites like JSTOR, Archive.org, or other educational resources with papers available for download.

That being said I ALSO recommend (I obviously have not read all of these but they are either in my library or I intend to add them)

📚 Celtic/Irish Pagan Books

The Morrighan: Meeting the Great Queens, Morgan Daimler

Raven Goddess: Going Deeper with the Morríghan, Morgan Daimler

Ogam: Weaving Word Wisdom, Erynn Rowan Laurie

Irish Paganism: Reconstructing Irish Polytheism, Morgan Daimler

Celtic Cosmology and the Otherworld: Myths, Orgins, Sovereignty and Liminality, Sharon Paice MacLeod

Celtic Myth and Religion, Sharon Paice MacLeod

A Guide to Ogam Divination, Marissa Hegarty (I'm leaving this on my list because I want to support independent authors. However, if you have already read Weaving Word Wisdom this book is unlikely to further enhance your understanding of ogam in a divination capacity)

The Book of the Great Queen, Morpheus Ravenna

Litany of The Morrígna, Morpheus Ravenna

Celtic Visions, Caitlín Matthews

Harp, Club & Calderon, Edited by Lora O'Brien and Morpheus Ravenna

Celtic Cosmology: Perspectives from Ireland and Scotland, Edited by Jacqueline Borsje and others

Polytheistic Monasticism: Voices from Pagan Cloisters, Edited by Janet Munin

📚 Celtic/Irish Academic Books

Early Medieval Ireland 400-1200, Dáibhí Ó Cróinín

The Sacred Isle, Dáithi Ó hÓgáin

The Ancient Celts, Berry Cunliffe

The Celtic World, Berry Cunliffe

Irish Kingship and Seccession, Bart Jaski

Early Irish Farming, Fergus Kelly

Studies in Irish Mythology, Grigory Bondarnko

Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland, John Waddell

Archeology and Celtic Myth, John Waddell

Understanding the Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Past, Edited by Katja Ritari and Alexandria Bergholm

A Guide to Ogam, Damian McManus

Cesar's Druids: an Ancient Priesthood, Miranda Aldhouse Green

Animals in Celtic Life and Myth, Miranda Aldhouse Green

The Gods of the Celts, Miranda Green

The Celtic World, Edited by Miranda J Green

Myth and History in Celtic and Scandinavian Tradition, Edited by Emily Lyle

Ancient Irish Tales, Edited by Tom P Cross and Clark Haris Slover

Cattle Lords and Clansmen, Nerys Patterson

Celtic Heritage, Alwyn and Brinley Rees

Ireland's Immortals, Mark Williams

The Origins of the Irish, J. P. Mallory

In Search of the Irish Dreamtime, J. P. Mallory

The Táin, Thomas Kinsella translation

The Sutton Hoo Sceptre and the Roots of Celtic Kingship Theory, Michael J. Enright

Celtic Warfare, Giola Canestrelli

Pagan Celtic Ireland, Barry Raftery

The Year in Ireland, Kevin Danaher

Irish Customs and Beliefs, Kevin Danaher

Cult of the Sacred Center, Proinsais Mac Cana

Mythical Ireland: New Light on the Ancient Past, Anthony Murphy

Early Medieval Ireland AD 400-1100, Aidan O'Sullivan and others

The Festival of Lughnasa, Máire MacNeill

Curse of Ireland, Cecily Gillgan

📚 Indo-European Books (Mostly Academic and linguistic)

Dictionary of Indo-European Concepts and Society, Emily Benveniste

A Dictionary of Selected Synonyms in the Principle Indo-European Languages, Carl Darling Buck

The Horse, the Wheel and Language, David W. Anthony

Comparative Indo-European Linguistics, Robert S.P. Beekes

In Search of the Indo-Europeans, J.P. Mallory

Indo-European Mythology and Religion, Alexander Jacob

Some of these books had low print runs and therefore can be difficult to find and very expensive... SOME of those books can be found online with the help of friends... 🏴☠️

library genesis might be a great place to start... hint hint...

#books#book#resource#blackcrowing#pagan#paganism#irish mythology#celtic#irish paganism#irish polytheism#celtic paganism#celtic polytheism#celtic mythology#indo european#indo european mythology#historical linguistics#paganblr#masterlist#irish reconstructionism#irish reconstructionist#celtic reconstructionist#celtic reconstructionism#masterpost

96 notes

·

View notes