#if i don't color in wallace's pants then is he not wearing pants

Text

✨🍸 Day 1: Everyday

Drew this for Scollace Week 2023 over on Twitter!! Thought I should share here as well. I like to think Scott and Wallace watch a lot of movies together. That's where they have some of their most in-depth conversations.

#scott pilgrim#scollace#neo's art tag#if i don't color in wallace's pants then is he not wearing pants#much to consider#i really should share more of my uncolored pieces#personally i kind of like that sketchy style but i still don't share it that often lol

758 notes

·

View notes

Text

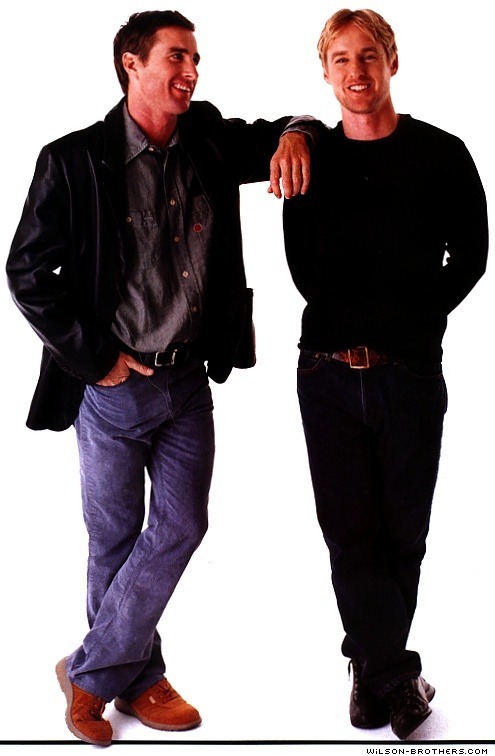

Bitter Sweet Dreamers - Los Angeles Magazine, December 2001

Bitter sweet dreamers: in their comedies Bottle Rocket, rushmore, and now The Royal Tenenbaums, Wes Anderson and his friends Owen and Luke Wilson skirt irony in favor of sincerity. They are the perfect funnymen for an unfunny world.

By Amy Wallace

YOU HAVE TO SEEK OUT VAHRAM. IF you need to know about Wes Anderson, if you really must understand, then you have to find Vahram. Vahram knows. Oh, you can read the impossibly detailed scripts Anderson writes. You can watch his funny, melancholy movies. You can talk to his best friend and writing partner, Owen Wilson, or Owen's actor brother, Luke. If you don't mind waiting--and waiting--you can sit down with the filmmaker himself and discuss why he was obsessed by limousines as a child or why Linus is his favorite Peanuts character.

But to comprehend Wes Anderson, the 32-year-old writer-director who has been called the next Martin Scorsese by Martin Scorsese, you have to get into his head. And to get into his head, you have to get into his pants. That's where Vahram comes in.

Vahram is Anderson's tailor. His name rhymes with arm, but Anderson calls him "Varn," which rhymes with barn. Vahram doesn't care. Vahram knows Anderson's inseam, where he wants to be suppressed and where he wants to stick out. Vahram has touched Anderson where few other men would dare. As much as anyone, Vahram has taken Anderson's measure.

"I got a lot of customers with their own bugaboos," Vahram says. He is sitting in his Manhattan workshop, a narrow room stacked ceiling high with bolts of fabric. Most people, he says, want to be taller or thinner or broader in the shoulders. The six-foot-two-inch Anderson wants to be understood. "He wants to bring you into his world."

So far that world consists of three films: Bottle Rocket, Rush, more, and The Royal Tenenbaums, which comes to theaters December 14. Anderson's movies are comedies, but they are also sad, filled with messy emotions. Loss. Betrayal. Contrition. Regret. He finds laughs not in jokes but in juxtapositions. His movies aren't gross or mocking or savagely ironic. They are sincere, observant, nonjudgmental.

Anderson likes to wear traditional suits in wacky colors--a wardrobe whose meaning I've had time to ponder. For weeks I have hounded his assistant, his agent, his producer, and a phalanx of publicists connected with the movie studio releasing his new film. Everyone says Anderson is on board, excited to be interviewed. Finally he summons me to New York for a lunch meeting. Then he cancels lunch.

Vahram could be a character in one of Anderson's movies--wry, modest, very much his own man. His name, however you choose to say it, fits right in among the Dignans, the Royals, the Kumars, and the Pagodas who populate Anderson's films. His bearing, too, is Anderson-esque: He's a plain-talking guy who looks on the bright side and calls his father "Pop." When Vahram talks about clothes, it's as if he's run Anderson's psyche through his sewing machine.

Anderson has figured out that he can use wardrobe to alter reality. Wear a white turtleneck under your rust-colored suit jacket, and you are professorial. You are rakish. You are Carl Sagan. Wear a purple turtleneck with that same rust-colored jacket, and you are Sagan-ish, Sagan-like, but with a twist. People receive you with trepidation, perhaps, but also with curiosity and a willingness to be surprised. In Anderson's hands, weirdness is a tool to make you lean closer, to make you listen.

In Vahram's 5th Avenue shop, the tailor makes Anderson's seersucker and pin-striped suits. He cuts, tucks, and hems the cashmere herringbone suits and the fine-wale corduroy suits in royal blue, egg white, and burnt orange. "Not a lot of people are going to get this kind of color," Vahram says. That's why he has to order it special.

Vahram's suits fit Anderson like the tiny pinafore on the overgrown Alice in Wonderland. The shoulders are too narrow. The pant legs are abbreviated so, as Vahram puts it, "Wes's whole sock is showing." The jackets button over Anderson's sternum, and the pockets hit him high, just under his rib cage, so when he jams his hands in--which he often does--his long arms form two sideways Vs, like he's dancing the funky chicken.

"It's his own thing," Vahram says, pinching a swatch of corduroy between his thumb and forefinger. "He likes everything minimalist. I'm always screaming at him. He don't want to hear it. He knows what he wants in his head."

IN WES ANDERSON'S HEAD, THE COLORS ARE brighter, the bookshelves are meticulously ordered, the bunk beds aren't just made--they look like you could bounce a silver dollar off them. In Anderson's head, a grown man would wear a blue gingham bow tie and a yellow gingham pocket square at the same time. In Anderson's head, Formica would come in only one color--that yellow-beige-with-fake-wood-grain that elementary school desks are topped with--and ideally it would have someone's name scratched into it. In Anderson's head, the string hanging from the lightbulb in the hall closet would have a green Monopoly house knotted to the grabbing end, not because any moviegoer could possibly see it on the screen but because a child would have tied it there, years ago, before everyone grew up and moved away.

As much as any filmmaker working today, Anderson makes films that reflect a distinct sensibility. Some people think his love of detail is precious, but they're wrong. Anderson sees as a child sees--vividly, completely, as if for the first time. In Bottle Rocket and Rushmore, that focus helped him create a style that translates more as fable than as fiction. With a $25 million budget (more than twice that of Rushmore) and a large, big-name cast, The Royal Tenenbaums is his most ambitious and risky undertaking. It has a whimsical innocence that

will be familiar to Anderson fans, but it also peers intently into life's dark corners.

Set in New York City, the film revolves around a family of troubled geniuses. Gene Hackman, the self-serving con man who is the Tenenbaum patriarch, yearns to reconnect with his oddball children. Hackman's estranged wife, an archaeologist played by Anjelica Huston, is falling for her clumsy, gingham-wearing accountant (Danny Glover). The three Tenenbaum siblings (Gwyneth Paltrow, Ben Stiller, and Luke Wilson) are over-the-hill prodigies whose relationships with friends (Owen Wilson) and lovers (Bill Murray) are overshadowed by past failures. They inhabit a world where bedroom doors have five deadbolts, the wallpaper sports galloping zebras, and the butler wears pink.

It's like a hyperreality he's creating," says Stiller, who was so eager to work with Anderson that he committed to The Royal Tenenbaums before reading the script.

"If all the colors and all the other atmosphere is more extreme," says Glover, "the connectedness between the characters seems to be heightened."

"Wes is so specific about these details, and they're very personal to him," says Paltrow, who as Margot Tenenbaum wears the same mink coat and heavy black eyeliner in nearly every scene. "On set he's very much the boss. Very much in control. He's created a situation where he literally controls everything."

Anderson grew up in Houston. His mom, a real estate agent, used to be an archaeologist. She and his dad, who runs an advertising agency, split up when he was in the fourth grade. About that time, a teacher discovered that the only way to get Anderson to behave in class was to let him produce his own plays. Later he wrote, directed, and shot his own Super 8 films, using cardboard boxes as sets and his two brothers as stars.

Anderson continues to surround himself with intimates. For each of his films he has hired director of photography Robert Yeoman, production designer David Wasco, costume designer Karen Patch, and composer Mark Mothersbaugh. Then there's his younger brother, Eric, an illustrator. For The Royal Tenenbaums Anderson imagined the zigzag-patterned carpets and the rotary telephones and described them to Eric. Sometimes Eric would misunderstand. His brother would gently correct his sketches. "He'd say, `No, that shower curtain was supposed to be clear, not pink,'" says Eric. "The details give the movie a credibility. But they also create a sort of fantasy. It's almost more information than life has, in a way. It's both credible and, in a pleasant way, knowingly incredible."

Vahram understands. "Almost all the jackets in the movie that were single-breasted, only the middle of the three buttons actually buttons," the tailor says of the costumes he made for the film. "But he wanted the buttonholes there for all three. You can't really see it on the screen. But he wanted it there. Because in his head, that's the jacket he wants."

Anderson's closest collaborator is Owen Wilson. They met at the University of Texas--two intense, off-kilter guys who shared a love of classic literature, pulp westerns, and the Sunday funnies. They also shared a condo in Austin. Once, in order to keep the bigger bedroom, Anderson wrote a paper for Wilson about Edgar Allan Poe. The professor gave the paper an A and called it "magnificent and droll." Ten years later Wilson and Anderson still delight in calling things "magnificent and droll."

They were the kind of down-on-their-luck dudes who would stage a break-in just to get their landlord to fix the windows. When the ruse was discovered, they would convince the landlord to let them shoot a documentary about him and his pet snake--at his expense.

After college they made a short film starring Owen and his younger brother, Luke. Bottle Rocket screened at the Sundance Film Festival and eventually caught the eye of Polly Platt, the production designer who had worked with producer-director James L. Brooks on Terms of Endearment and other films. Platt showed the short to Brooks, who convinced Columbia Pictures to finance a

feature-length version. Brooks and Platt fought to keep the novice director, the first-time screenwriters, and the no-name cast on board.

When the feature-length Bottle Rocket was released in 1996, few people got it. Mostly that was because Columbia, spooked by negative responses to test screenings, dumped the movie. But it was also because the world that Anderson and Wilson invented was so without precedent that many weren't sure what to make of it. The film follows three wanna-be criminals on a bungled heist. Owen Wilson plays Dignan, the trio's aspiring mastermind, who clings to the verbal swagger of a tough guy ("You're gonna see a side of Dignan that you haven't seen before. A sick, sadistic side!") even as he dons a yellow jumpsuit that evokes a trick-or-treater more than a hardened safecracker. Luke Wilson plays the gentle Anthony, a former mental patient who seems saner than anyone else. Bottle Rocket, which cost $7 million, tanked. Critics, however, not only raved, they sounded grateful. The Los Angeles Times's Kenneth Turan applauded the film's "exact sense of itself."

Rushmore, which Anderson and Owen Wilson also cowrote, was re, leased by Disney in 1999. Platt recalls that Anderson, still bruised by how his first film was received, asked her, "I don't have another Bottle Rocket on my hands, do I?" He need not have worried.

Rushmore's Max Fischer, a 15-year-old prep school student who excels at extracurriculars but is flunking out, is a classic Anderson-Wilson character. He has outsize ambitions that dwarf his ability to fulfill them. He appears to be the only one who sees the world precisely the way he does. The language he uses is elevated--partly borrowed from a bygone era, partly rooted in popular idiom. He is optimistic, even when there is no reason to be. He isn't cool, but neither is he a quitter. He spends half the movie decked out in a dark green velvet suit that no teenager would be caught dead in. Somehow that makes him more poignant, more heartbreakingly real. The film, which cost about $11 million to make, took in $17 million and put Anderson on the map.

Platt says Anderson has a rare gift--a visual certainty. He knows how each frame should be com, posed. "Not many men are born with that," she says. "He's a natural-born moviemaker." Brooks agrees: "He's entirely original. Wes makes futility look good."

Although Anderson cites many influences, from Roald Dahl to John Cassavetes to the Kinks, his films--unlike so many these days--do not come loaded with a predictable set of cultural reference points. He is difficult to describe in terms of what has come before. A few years ago The Guardian of London praised Anderson for nurturing a humanistic spirit "rather than denoting a lifetime spent watching the complete works of Scorsese." Yet last year, when Esquire asked Scorsese himself to identify the young filmmaker most likely to become "the next Scorsese," the master of grittiness chose the ungritty Anderson.

"I love the scene in Bottle Rocket when Owen Wilson's character, Dignan, says, `They'll never catch me, man, `cause I'm fuckin' innocent," Scorsese wrote. "Then he runs off to save one of his partners in crime and gets captured by the police, over `2000 Man' by the Rolling Stones. He--and the music--are proclaiming who he really is: He's not innocent in the eyes of the law, but he's truly an innocent. For me, it's a transcendent moment. And transcendent moments are in short supply these days."

Anderson is happy making relatively small movies, and he doesn't want to be a director for hire. So it's not as if he needs The Royal Tenenbaums to be a blockbuster. But everyone around him is hoping that this movie will reach more people than his previous two. A little advance press could, theoretically, help. I'm ready. I'm waiting. Anderson, however, is very, very busy. I'm told he wants to give me his full attention. Just not yet.

THERE IS A BLACK and, white photograph of Wes Anderson and the Wilson brothers that says who they are--and who they're not. It was taken while they were making Bottle

Rocket. Anderson is typing on a computer, his back to the room. He's smiling, engaged. Owen Wilson is behind him, relaxing in a chair, mid chuckle. Luke Wilson sits nearby, his handsome face twisted into a goofy grimace. Both hands are clawing the air, as if he's being buried alive.

The picture, taken by a professional photographer who happens to be the Wilsons' mother, does not say "movie stars," though some people predict that's what the Wilsons are destined to become. The picture does not say "auteur," though Anderson has since earned that label. The picture is a portrait of three buddies enjoying a funny story.

James Brooks says the funny story is at the heart of the Anderson-Wilson collaboration. Their screenplays, he says, are "casually literary." If they ever stopped writing them, "nothing at all like those scripts would exist."

How Anderson and Owen Wilson work, however, is a mystery. Barry Mendel, a producer on Rushmore and The Royal Tenenbaums, says, "Frankly, I have never seen them working together."

Luke Wilson, who used to live with both of them in a big house in the Hancock Park section of Los Angeles, says, "They're like one of those couples that you wonder, `Are they really together?' It was kind of a closed-door affair sometimes. I get the feeling they both toss out names, ideas, fragments. But I couldn't tell you. And if I can't, I think probably nobody can."

The Wilsons and Anderson now live in different time zones--the director in a Manhattan apartment, the actors in a pretty white house in Santa Monica that Owen just bought.

Owen answers his front door barefoot. He's 5 foot 11 inches and wiry in khakis and a short-sleeved blue shirt with little red and green flowers on it. The shirt is buttoned up to his neck. One is struck by how many faces he has. Owen's agent, Jim Berkus, says he's more Jack Nicholson than Warren Beatty. The 33-year-old actor is not pretty, what with his boxer's nose and squinting eyes, but still, you can't take your eyes off him. There's mischief there, and a little vulnerability. Anderson compares Owen to Robert Redford, and at moments the label fits. Except that he can also look Like a doofus or a stoner, something Redford has never risked his image to perfect.

Once we are settled in his whitewashed living room, Owen says there is no secret to how he and Anderson write. They always start with characters, creating bits of dialogue, passing them back and forth. Over time--a lot of time--a story will emerge. "It's sort of the cart leading the horse," Owen says, sinking into a huge armchair. "We don't know what it's gonna be. We're just talking, trying to get each other laughing."

The Wilsons grew up in Dallas, but that alone doesn't account for Owen's distinctive voice, which is nasal with just a hint of twang. He speaks slowly, musingly, placing a lot of emphasis on favored syllables.

"We just hole up together," he says. "And it always seems to disintegrate into us just going to the places we like to eat and both of us kind of telling stories to each other that we've both heard but that we still think are funny. Or getting on somebody we feel has wronged us in the past, like in college, and talking about that person for three days."

He gets up to show me a framed photo, a gift from Anderson: a heroic portrait of a man who's about to die. "This is something I could see us making a movie out of," Owen says. The man's expression is caught between a scowl and a smirk. "We could spend a week talking about that guy. But the way it eventually would come out from us, the guy wouldn't be quite so heroic." He laughs. "Or he'd be heroic in the very end, but he would have a lot of very cowardly things that he had done."

When Anderson and the Wilson brothers all lived together in Los Angeles, a Ping-Pong table dominated the living room. As Luke, now 30, recalls, they would "have rallies that only ended because we were laughing so hard." They'd be analyzing the way each game was going, and the awareness that everybody was so simultaneously aware broke them all up. "It'd be like,

`Yeah, it's a good rally'"--Luke pauses a beat--"`I can't believe it's not ending!'"--another beat--"`We're in-cred-ible Ping-Pong players!' You start moving back farther and farther from the table. It's like a U.S. Open match, where you walk around the table, changing sides, without even speaking."

That kind of sync is the foundation upon which the Anderson-Wilson alliance is built. Back in Texas they used to wander around bumping into people they thought were ludicrous or scary or askew, and they'd riff on what it was that struck them. Things are different now; that's what success does. Owen's asymmetrical face is suddenly everywhere on, screen: as a male model in Zoolander, as a born-again Christian in Meet the Parents, as a bumbling cowboy in Shanghai Noon. And there's more to come: Behind Enemy Lines with Gene Hackman, I Spy with Eddie Murphy, and the sequel Shanghai Knights with Jackie Chan.

Owen and to a lesser extent Luke (who's been in the recent hits Legally Blonde and Charlie's Angels, among other films) might be thought of as the anti-Afflecks--rising young actors who work hard, steal the show, but don't seem much interested in celebrity.

On a bookshelf behind Owen is another framed photo taken by their mother. Owen, 8, and Luke, 5, are sitting with two women--the oldest living twins in Massachusetts. A wide-eyed Owen is telling a story, his hands clasped awkwardly in his lap. He has Luke and the old ladies transfixed. "I'm sitting there on the side, with a kind of funny expression, watching Owen," says Luke. "It does seem like we're kind of little partners."

When Owen looks at the photo, he focuses on the women's reaction. "Maybe that's our audience," he says. "Senior citizens!"

In The Royal Tenenbaums, one of the first scenes Anderson and Owen Wilson wrote was for the character Eli Cash, a hot young novelist--a Cormac McCarthy knockoff played by Owen. The first we hear from him is when he reads an excerpt from his new novel, which is based on the supposition that General Custer survived Little Bighorn. Not that either Anderson or Wilson knew any of this at first. They were just writing for the joy of capturing Cash's faux-western voice.

"The crickets and the rust beetles scuttled among the nettles of the sage thicket," Cash reads aloud. The script specifies that he wear a fringed white buckskin jacket and a short-brimmed Stetson. "`Vamanos, amigos,' he whispered, and threw the busted leather flintcraw over the loose weave of the saddlecock. And they rode on in the friscalating dusklight."

"Friscalating," Owen whispers to me. "Wes made up that word. It's what you see on the horizon at sunset with the light kind of shimmering." Only after they'd written the scene, Owen admits, "did we try to figure out, Well, how can we get that in?"

With language, as with clothes, these guys like to try things on to see whether they're ostentatious or genuine, full of braggadocio or yearning. They love how people express themselves as they fumble through life, because they're fumblers, too. Owen was expelled from prep school; both had average grades but fancied themselves Ivy League material. Anderson used to say he was going to transfer to Yale, and he even dressed the part, donning L.L. Bean duck boots.

Owen purses his lips to express how sweltering a pair of rubber boots feels in the middle of a Texas summer. Then it's as if the talk of Anderson's wardrobe sobers him up. He doesn't want his friend's aesthetic flourishes to be misinterpreted as self-congratulatory pretension. The emotions are what matters in the movies, Owen says; the fabric they're draped in is just a way to keep them fresh. "Wes and I don't want to do something that's corny or sentimental. There aren't too many original emotions. So the world that Wes creates is a way to keep it original."

Like everyone else, Owen frequently refers to Anderson's head. I ask him how he would describe what's inside. "It's a lot more recognizable," he says, "than people might think." Then he mentions Vahram: "The thing about all that stuff with--what's the guy's

name? Varn?--is that Wes has a sense of humor about it. He recognizes that it's funny. It's kind of like winking. You take away that stuff, that funny stuff, and Wes is, like, sensitive."

WHEN WES ANDERSON talks, he thinks about what he's saying so keenly that sometimes the words just stop. There are long pauses; he's giving himself the time to get it right. After an advance press screening of The Royal Tenenbaums at the New York Film Festival, he takes questions from the standing-room-only crowd. As he grips the microphone in both hands and squints into the lights, he is asked if the film is about redemption.

"So much of the story is about these people accepting that they're not what they once were," Anderson says. "And then they sort of have to struggle with that. And it causes so much pain." He goes silent. "It wasn't like I planned for that to happen in the story. It just sort of emerged. More and more it revealed itself. That there would be healing, sort of? Even though that's a word I'm reluctant to use, that sort of became the center of it."

He looks out vaguely into the crowd to make sure everyone understands. "I think that's what the whole movie is about," he says mildly, as if he'd be open to other interpretations. He pauses again. "Did that answer that at all?"

The next afternoon Barry Mendel, the producer, asks me to be on call between the hours of 3 and 8 p.m. At 8:05 the phone rings. Anderson is ready. Come, Mendel says, at once. I walk into a dimly lit sound-mixing studio in the Brill Building, and there Anderson is. He has misbehaving brown hair and round glasses with clear plastic rims. He wears a baby blue button, down shirt and seersucker trousers that grab his skinny frame way below the navel. Pale yellow socks are visible above his Nikes.

The Royal Tenenbaums is to have its official festival premiere in two days, but Anderson and a team of mixers and editors are still tweaking the film's color timing and making sure the music doesn't overpower the dialogue. "I don't know if stubborn is the correct word," says director of photography Yeoman. "He's very persistent. He's tenacious. He does not want to compromise his film on any level."

Before the script was written, for example, Anderson knew he wanted Gene Hackman to play Royal Tenenbaum. They met for tea at the Essex House, and Anderson told the actor he was writing a part for him. Hackman told him not to bother. He hadn't found most writers to be successful at tailoring parts for him. Anderson did it anyway and then cast the movie around him. At the last minute Hackman gave in. If he hadn't, Anderson says he might not have gone forward.

When we sit down Anderson is at the end of what he calls "the eighth day of a three-day mix." "We're going to the wire," he says. He looks pale and exhausted. "All these movies are kind of confections," he continues. "They're this arrangement of things all put together. The whole souffle can fall--it doesn't have much genre to rely on--and there are definitely people who think it's precious. But the idea is to make this, like, self, contained world that is the right place for the characters to live in, a place where you can accept their behavior.

"The last thing I want is for it to be thought of as quirky, because there's nothing we've done to try to make it weird, you know? Everything is in there to try to make it interesting or compelling or funny." He pauses. Weird for weird's sake, Anderson says--"that's the last thing it wants to be."

The Royal Tenenbaums started with place, not plot; it was going to be a "New York movie." On a notepad, in no particular order, Anderson made a list of the things he thought should inspire it. There were titles of films (Louis Malle's The Fire Within, Orson Welles's The Magnificent Ambersons), short stories and novels (J.D. Salinger's "Franny and Zooey," F. Scott Fitzgerald's "Babylon Revisited" and "May Day," Edith Wharton's The Age of Innocence), and pieces of music (a Maurice Ravel string quartet and a few Velvet Underground cuts).

We talk for a while about his ideas

for the soundtrack, which at that point includes the Beatles' "Hey Jude," Nico's "These Days," the Clash's "Rock the Casbah," and Elliot Smith's "Needle in the Hay." We talk about what he calls Luke Wilson's "soulful" portrayal of the failed tennis pro Richie Tenenbaum--an understated and startling performance that is the best acting of the younger Wilson's career. When I mention Anderson's girlfriend, who appears briefly in the film, he looks stricken.

"Yeah, Jennifer," he says, sounding two decades younger than he is. "She's a New Yorker. But you know, I don't know. It's embarrassing."

Anderson has a facility for tapping into what it feels like to be 12. By maintaining his connection to what slighted or thrilled us as kids, he has developed a more sophisticated grasp of what motivates us as grown-ups. He's not cute. He's not juvenile. It's just that suddenly childhood doesn't seem that long ago.

When Anderson was a child he filled a sketchbook with drawings of fancy houses. "There was this certain phase I went through where I was really obsessed with being rich. So I was fairly interested in Rolls-Royces and mansions," he says. Has that obsession gone away? "Yeah--at least, hopefully, I have a lot more irony about it now."

"Kids get embarrassed," he says, recalling how, for the longest time, he refused to accept that his parents had separated. "Somebody says, `Your parents are getting divorced,' and you're like, `No! No! Where did you hear that? That's so wrong. They're figuring some stuff out.'"

I ask if he would ever direct a movie he didn't write.

"I kind of feel like a children's book I could do, though I'd like to adapt the script myself," he says. "With a children's book you're sup, posed to make a separate reality. And I just feel like the details I would bring in would be better understood."

Anderson needs sleep. Promising to meet again the next day, he prepares to say good night. Then I mention Peanuts, and he brightens.

"The real thing I responded to is that Christmas special," he says, remembering the animated TV show in which the parents are always unseen and everyone wears the same outfit day after day. Anderson loved A Charlie Brown Christmas so much that he has put its tinkly music in both Rushmore and The Royal Tenenbaums. "It's very sad," he says admiringly. "And very funny."

"We always had the books, growing up. I especially liked Linus, because he was kind of a genius, but he still carried a blanket and sucked his thumb," he says, straightening his wrinkled seersuckers. "I had this book that said Charles Schulz skipped a grade. Now I'm like, `Why were we so into the fact that in third grade Schulz got all As?' But at the time I was really interested in somebody who could skip grades. I was really hoping to skip a grade." He is quiet for a moment. Then, Linus-like: "I never skipped a grade."

We share a cab uptown. Anderson notes that in the aftermath of the attacks on the World Trade Center, New York City sidewalks, even in Times Square, are strangely empty at night. He says the tragedy has only made him feel more loyal to his adopted city. It has occurred to him, he admits, that when The Royal Tenenbaums comes out, people may not be the least bit interested.

But the opposite seems to be true. I remind Anderson about a man who approached him after seeing the movie at a screening earlier in the week. A third-generation New Yorker, he wanted to thank the director for creating such an idealized vision of his city. "I love your New York," the man said as Anderson shook his hand shyly. "I really appreciate it right now."

Before the cab drops Anderson off, I compliment him on his royal blue blazer. "Varn made this," he says, pleased that I've noticed. He smooths the fabric lovingly, and for a moment he's somewhere else. He's inside the walkin closet that is his head--a place of stored memories where the clothes are less important than how they make you feel. "Corduroy is really great," he says, earnest. "It used to be what I wore to school every day. You know, it can be almost like velvet

sometimes.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

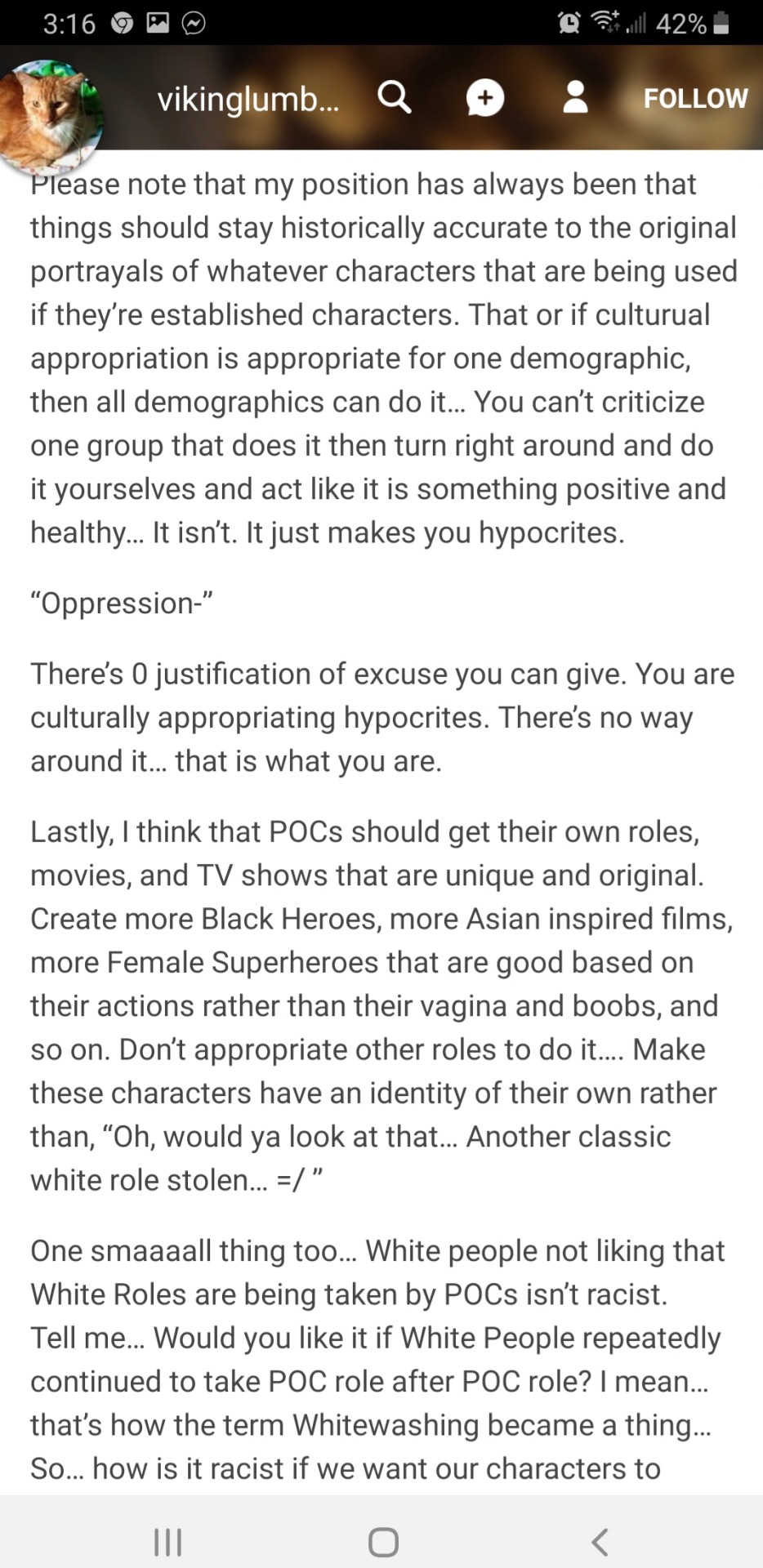

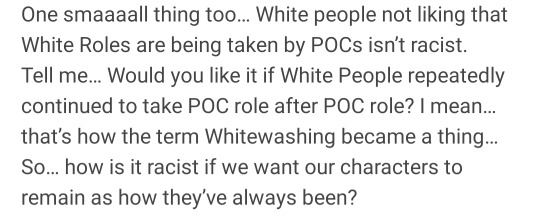

@iriswestsallen

Since you blocked me, I'll respond this way.

Did you literally read any of my post...? At all?

For those of you who are curious:

-‐--------

#1. If you ACTUALLY read what I said you will notice that I am PRO POC and Female Characters.

Do I think that there needs to be some sort of Diversity Quota or, more specifically, MORE POCs or Female characters? Not necessarily.

I don't choose the types of content I enjoy based on meaningless, superficial, aspects of a character. A person being Black, White, Asian, or Female doesn't really mean much to me. If I like the premise and the characters are cool, in depth, and interesting then I'd probably give it a chance.

With that being said, I don't see any problem whatsoever if there ARE more POC or Female based movies/etc. However, if the advertising or main point of a story IS a person's skin color or gender that ISN'T due to the film/series being a historical based movie, then I will most likely not watch it. It is either a propoganda piece or a movie that I feel wasn't targetting me/or piquing my interest. Example: Sisterhood of the Travelling Pants, Mean Girls, Devil Wears Prada, Twilight, etc. (I mean... Twilight's Universe and take on Vampires was very unique and interesting to me but the films were... meh? They weren't bad.)

#2. Appropriation of established characters irks me. A lot. Clark Kent/Superman, Bruce Wayne/Batman, Mary Jane, Peter Parker/Spiderman, Hiemdall, Brunnhilde/Valkyrie, etc... Those are established characters and some are established entities of significant Culturue(s) in Europe... Just to name a few anyway. They were introduced as being White and Straight. Some were invented and worshipped, even now, as Dieities. I don't think any of those figures, as well as MAAAANY more, should be race, gender, or sexuality changed.... at all...

If you want a Black Spiderman you have Miles Morales. If you want an Asian Spiderwoman, you have Cindy Moon/Silk. If you want a Female Batman you have Katherine Kane/Batwoman. If you want a Black Flash you have Wallace West/Kid Flash. (His story is a bit complicated.)

You know what's even BETTER than being side versions of characters like Batman, Superman, Flash, Spiderman, etc.? Character's having their OWN identity.

Cyborg is not an side version of a White Character. Cyborg is his own hero. An ORIGINAL hero. Same thing as Static Shock, Black Lightning, Black Panther, Storm, Luke Cage, Blade, Misty Knight, Falcon, FUCKING SPAWN, Katana, Karma, Silver Samuri, Cassandra Cain, Doctor Light, BLADE, Brother Voodoo, etc.

All of those, too my knowledge, are all ORIGINAL characters. They weren't offshoots of White Characters, they weren't reinventions of White Characters, and they aren't token characters. They stand on their own. They don't NEED another White Hero to prop them up and they don't need to DEPEND on another White Hero to make them popular.

Miles is only popular becuase he's a Black Spiderman. (I mean... If he wasn't a Spiderman I honestly dunno if people would know him.) Batwoman is only popular because she's literally the Female version of Bruce Wayne.... (Again, if she wasn't called Batwoman I don't think many people would know her.)

Do you get my point?

Lastly, on this subject, my stance will always remain the same. If a character is introduced as Black, White, Asian, Straight, Gay, Female, Male, and so on, they STAY Black, White, Asian, Straight, Gay, Female, Male, etc. Race changing, Gender Bending, and Sexuality Shifting is not and should not be acceptable. Alternate Universes are one things, paradies are one thing, and all that are unique in those changes, but continuity is something that should be upheld...

You can't create an Indian Spiderman and call him Peter Parker... Peter Parker isn't Indian. Peter Parker isn't bi, or gay, or whatever else you add on to that. Peter is Straight. The same goes for other established characters. Cyborg isn't White. Blade isn't Gay. Mar-Vell isn't a woman. Do you see what I mean?

#3. Lastly, wanting to keep established White Characters as White is NOT racist!

Why?

Well.. Let ask you this:

Are Black People racist for wanting Black Characters to stay Black?

I'd say no. Of course not. They just want characters that were created to be like them and are part of their culture to STAY that way. It is NO different with White People and Peter Parker, Clark Kent, Bruce Wayne, Mary Jane, Valkyrie, Hiemdall, and so on. They are a part of White Culture... How and why is it racist if we want them to STAY that way when Black people AREN'T racist for wanting THEIR characters to stay that way for them?

Does that not seem hypocritical? That there's a double standard at play?

"But Whitewashing is opression. When a Black Person is playing a White Role it is to help represent them and good for the children to see that."

So you're literally saying that Culturual Appropriation and Race-Washing is okay...

You know what would be better? Creating INDEPENDENT and ORIGINAL POC Roles/Characters that are UNIQUE without IMPEDING on ESTABLISHED CHARACTERS!

You want a Black, Asian, or whatever love interest for Spiderman? INVENT one. You want a Black love interest for The Flash? INVENT one. You want an important POC character in a movie? INVENT one...

That way you are not appropriating ANYTHING and are creating original, independent, characters.

Oh... and one last thing...

If you reblog a response to me, but block me before I can even give a response, then you are a coward... I'm sorry, but you are. Either say something to my face or don't say anything at all.

This is just a general statement. Not aimed at anyone. Buuut there it is.

#discourse#dc#dceu#dc comics#marvel#mcu#marvel comics#disney#ariel#iris west#poc#poc casting#whitewashing#unpopular opinion#chat with me#im open to discussions#racism#blocked

11 notes

·

View notes