#it is als not a prestige show that gives them awards

Text

I'm begging y'all to learn about how the industry works before writting 5k words on why your niche show is the most popular show in a streaming service and it should be renewed because u love it. Take that energy and put it into something that matters, workshipping showrunners is always a bad idea and you shouldn't have to work this hard to get them more money

#this is soooo embarrassing#babes it's all about the money if a show was profitability it wouldn't get cancelled#that's not how thing works nobody jas a vendetta against your show#think about the fact that a niche show that attracts internet users will never be a driving force in a svod#they only make money by getting new subscribers#how many of ur internet friends you think are subscribing to max to watch the show??#it is als not a prestige show that gives them awards#and since I'm already here#thinking that by working yourself ro the bone to get the show another season the showrunner will reward you with a good story???#delusional! they are not obligated to give you what you want just because you are the audience

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Praise of Patrick Wilson, Scream King

The classically trained actor has been acclaimed for his work onstage. But in ghost stories like “Insidious” and “The Conjuring,” he’s proven to be a master of horror.

Patrick Wilson in “The Conjuring: The Devil Made Me Do It.” The actor brings both an intensity and a reassurance to the franchise. Credit...Warner Bros.

By Calum Marsh, The New York Times.

June 6, 2021

Ed Warren is sitting in a musty living room in North London, trying to establish contact with a demon. Behind him sits a little girl, said to be possessed. The demon won’t talk, she insists, unless he faces away and gives him some privacy. With his back to the girl, Ed gets down to business. “Now come on out and talk to us,” he says brightly.

Out comes the demon, cackling and taunting in a fiendish, guttural voice, like a cockney Tom Waits. He wants to rattle Ed, but as played by Patrick Wilson, Ed’s not easily rattled. Alongside his wife, Lorraine, he works as a paranormal investigator, and this is hardly his first tête-à-tête with a malignant spirit. “Your father called you Edward,” the demon snarls, trying to get under his skin. But Ed just rolls his eyes and shakes his head impatiently. “You’re not a psychiatrist, and I’m not here to talk about my father,” he says. “Let’s get down to business. What do you say?”

This scene in “The Conjuring 2” (2016), the sequel to the sumptuous, vigorously terrifying “The Conjuring,” encapsulates what these hit movies do so well. The director James Wan shoots the entire conversation in one long, unbroken take, zooming in so slowly that the movement of the camera is virtually undetectable. The demon, in the background, is a sinister blur. Instead, our attention fixes on Ed, staring ahead.

In “The Conjuring 2,” a scene with a demon in the background depends entirely on the range of emotion in Wilson’s face.Credit...Warner Bros.

Wan is demanding a lot of his lead here — the effect of the scene hinges entirely on Wilson, and without a cut, in extreme close-up, he has nowhere to hide. But he proves more than capable. The five-minute scene is an acting tour de force, and one you might not expect in the middle of a haunted house picture.

The range of emotions in Ed’s face is mesmerizing. Wilson, a classically trained actor with a background in stage dramas and Broadway musicals, is able to do so much with subtle changes in the cast of his eyes and his manner that you can tell from moment to moment exactly how he is feeling — apprehensive, irritated, disturbed, chagrined. For a split second, his composure waivers. Then he steels himself, blinks and gains it back. This is a frightening confrontation, to be sure. But it’s compelling mainly for the intensity that Wilson exudes.

Of course, Wilson, who plays Ed again in the new sequel, “The Conjuring: The Devil Made Me Do It,” has been a known talent for more than 20 years. In the early 2000s, he earned Tony Award nominations for his starring roles in the musicals “The Full Monty” and “Oklahoma!,” and in 2003 he was nominated for an Emmy and a Golden Globe for “Angels in America,” the television adaptation of Tony Kushner’s play in which he played a gay Mormon attorney struggling with his sexuality during the AIDS crisis.

“Angels in America” is a more straightforward acting showcase, and Wilson’s performance, full of stifled passion and moral compromise, is sensitive and powerful. He shares scenes with Al Pacino and Meryl Streep, but his is the most affecting turn.

Like many celebrated stage actors before him, Wilson soon tried to parlay his growing prestige into movie stardom. The results have been mixed. Over the next few years, he appeared in a number of high-profile Hollywood movies, but many of them were poorly received, like the limp remake “The Alamo,” the over-the-top domestic thriller “Lakeview Terrace” and the big-screen version of “The A-Team.” When he starred as the reluctant superhero Nite Owl II in Zack Snyder’s ambitious adaptation of the graphic novel “Watchmen,” critics complained that he was miscast.

It was in 2010 that Wilson found an unexpected niche: the horror movie. That year, he starred in “Insidious,” an early experiment in the producer Jason Blum’s low-budget horror revolution and a creepy, atmospheric ghost story with a playful touch of David Lynch.

Wilson played Josh Lambert, who, for the first two acts, seems like the typical horror movie patriarch: stalwart, steadying and, as the haunting begins to escalate, staunchly disbelieving. He spends a lot of time reassuring his wife that she must be imagining the scary things she’s been seeing around the house and that ghosts aren’t real. Until it turns out that ghosts are real, and that in fact Josh has a history with them.

Patrick Wilson opposite Rose Byrne in “Insidious.” He does so much with a stock character. Credit...FilmDistrict

In “Insidious: Chapter 2,” he’s an evil spirit pretending to be human to his family, which includes Barbara Hershey, left, Ty Simpkins and Byrne.Credit...Matt Kennedy/FilmDistrict

At the end of the second act, it’s revealed that Josh had an encounter with a demon as a child, but that his memories had been repressed. And Wilson, as he accepts this information, manages to subtly disclose a lifetime of trauma. With a faint shifting of the eyes and delicate tensing of the muscles, he conveys flashes of bone-deep dread lingering at the back of his subconscious. Suddenly, a familiar and somewhat flat character gains a new dimension, as Wilson transforms a stock type into someone dynamic and real.

Wilson reprises the part in “Insidious: Chapter 2,” with Josh’s body inhabited by a malevolent demon and Josh’s soul trapped in the spirit world. As the demon-Josh, Wilson has the difficult task of playing an evil spirit pretending to be human, convincing his loved ones that he’s the same old Josh as he secretly conspires to kill them. Occasionally, the mask of the happy husband slips, and Wilson reveals a glimpse of frenzied menace. It’s a terrifying performance reminiscent of Jack Nicholson in “The Shining.”

Ed Warren is Josh Lambert’s opposite. Ed’s role in “The Conjuring” movies is a stabilizing presence.

He and Lorraine (played by the wonderful Vera Farmiga) are called on to investigate happenings that seem to defy scientific explanation, and their arrival on the scene, usually after ghosts and demons have done some preliminary haunting, is accompanied by a sense of reassurance that is rare in horror movies. Wilson gives the calming impression of unflappable expertise, an almost fatherly stolidity, not unlike what Tom Hanks brings to many roles. However frightened we may be, we’re heartened that Ed knows what he’s doing.

Patrick Wilson with Vera Farmiga in “The Conjuring.” Their chemistry helps ground the movie.Credit...Michael Tackett/Warner Bros.

Ed is a man of God, investigating the demonic possession on behalf of the church, and one of the most striking things about Wilson’s performance is the intensity of his religious conviction. When he thrusts a cross at a spirit to dispel its power or reads Scripture in Latin to save the day, he doesn’t seem to be simply holding props or quoting dialogue but to regard these objects and rituals with palpable awe. He makes you feel Ed’s faith, as well as his belief in evil and the supernatural. It makes the scary stuff scarier and feel more real.

Wilson and Farmiga’s screen chemistry has been widely praised, but it’s difficult to overstate just how potent they are together. Their warmth and tenderness are a crucial reprieve from the pulse-quickening horror around them, and the affection they show one another is appealing precisely because it contrasts so sharply with the rest of the action. They are so magnetic that their minor roles at the beginning of the “Conjuring” spinoff “Annabelle Comes Home” practically spoils the rest of the movie: Having had the pleasure of watching them at the start, you’re disappointed to see them leave.

Shortly after Ed’s confrontation with the demon in “The Conjuring 2,” he notices an acoustic guitar in the corner of the same room. The family of the possessed little girl hands it over to him, and he proceeds to imitate Elvis Presley and sing “Can’t Help Falling in Love” in its entirety. The scene does not advance the plot. It’s not a misdirect; it doesn’t culminate in some twist or revelation or jump scare. The openness and gentle humor Wilson embodies is worth a dozen heart-stopping scares: Indeed, that openness and humor are what makes the scares worth anything in the first place. “The Conjuring 2” is already 136 minutes — a more prudent editor might have advised cutting the extraneous scene. But this moment, so earnest in its sentiment, is the heart of the movie. Like Wilson’s performance, it’s perfect.

#patrickwilson#pwilzfan73#actor#movies#verafarmiga#patrick wilson#theconjuringthedevilmademedoit#edwarren#lorrainewarren#insidiouschapter2#insidious#rose byrne#the new york times

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Life of Deception

This worldly life is like an unchaste woman, who is not satisfied with one husband. So, be satisfied with whatever Allah grants you from this worldly life.

Walking thereon is like walking in a land that is filled with beasts, and water that teams with crocodiles. That which causes delight, turns to be the source of grief. Pain is found in the midst of pleasures, and delights are derived from its sorrows.

Lusts were granted in abundance to humans, but those who believed in the unseen turned away from them, while those who follow their lusts were caused to regret.

The first category, are those, in which Allah says, “They are on (true) guidance from their Lord, and they are the successful.” (Al-Baqarah, 2:5)

However, the other category, are those to whom Allah says, “(O you disbelievers)! Eat and enjoy yourselves (in this worldly life) for a little while. Verily, you are the Mujrimun (polytheists, disbelievers, sinners, criminals, etc.).” (Al-Mursalat, 77:46)

When the successful ones are aware of the reality of this worldly life being sure of the inferiority of its degree, they overcame their vain desires for the sake of the Hereafter. They have been awakened from their heedlessness to remember what their enemies took from them during their period of idleness.

Whenever they perceive the distant journey they must undertake, they remember their aim, so it appears easy for them. Whenever life becomes bitter, they remember this verse in which Allah says, “This is your Day which you were promised ” (AI-Anbiya’, 21:103)

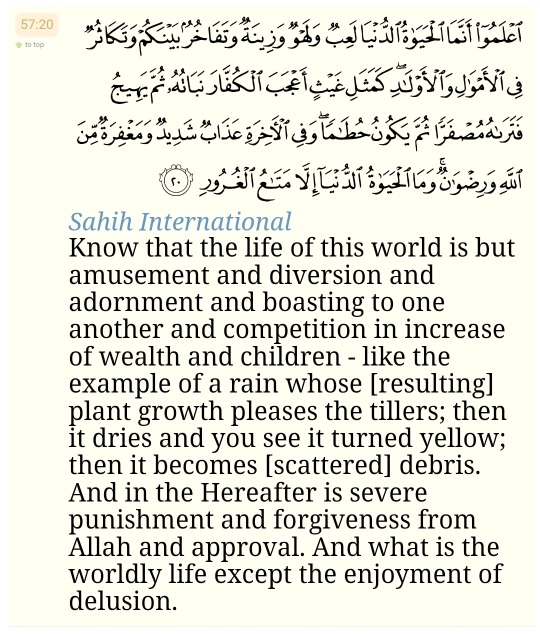

Surah Al-Hadid (its title meaning, ‘the iron’) talks about the reality of the transient life of this world. Several descriptive words are used to reveal to us its true reality. After that, Allah warns us to remember that the life of this world is nothing but a “deceptive enjoyment”

In order to see the real meanings being described by our Creator as He details to us the reality of the life of this world, it would be beneficial to ponder on the root meanings of the several Arabic words Allah has used in the above verse. All the meanings have been taken from Edward William Lane’s online Arabic-to-English Lexicon:

لَعِبٌ

(i) Play, sport, game, fun, joke, prank, or jest.

لَهْوٌ

(ii) Diversion, pastime, sport, or play; especially that which is frivolous or vain; that which occupies a person so as to divert him or her from that which should render him sad or solicitous/anxious/concerned.

زِينَةٌ

(iii) Decoration, finery, show, pomp, or gaeity.

تَفَاخُرٌ

(iv) Glorifying or boasting (viz. to each other), praising or commending own selves for certain properties or qualities, such as enumerating or recounting the particulars of their own ancestral nobility or eminence; or their honorable deeds. Contending for superiority by reason of honors arising from memorable deeds or qualities, or from parentage or relationship, and other things relating to themselves or their ancestors; also: boasting of qualities extrinsic to themselves such as wealth, rank or station.

تَكَاثُرٌ فِى الاٌّمْوَلِ وَالاٌّوْلْـد

(v) Contending, one with another, for superiority in number of (different types of) wealth and children.

مَتَـاعُ الْغُرُور

(vi) The word مَتَـاعُ means anything useful or advantageous viz. utensils, furniture, or food, and the word الْغُرُور means that by which one is deceived; something false and vain. In other words, the life of this world is a provision that is deceptive. It can be used to achieve the best end i.e. Allah’s pleasure and an abode in Paradise in the Hereafter, but is very deceptive in and of itself.

Allah has used a total of five terms and phrases to describe to us the reality of the life of this world in the Quran. Analysis of their meanings clearly reveals that indeed, the life of this world is such that it makes a believer lose focus of the Hereafter.

Consider this – games are fun to play. They cause us to get really involved in them, whether as participants, or as onlookers. The aspect of winning versus losing, or earning more points by achieving a target, enthuses the more keen ones among us to a state of physical and mental euphoria.

When anyone is involved in a game as a participant, whether he is playing outside, or playing a computer game indoors, he is distracted perhaps from more pending matters that require his attention. For some sports enthusiasts, tearing themselves away from a game to answer a call of nature, eat a meal, or pray an obligatory prayer also becomes difficult.

Now, with this picture in mind, we can see why Allah has called the life of this world “a game.” We get so involved in the “game” itself, in its short-term goals and enjoyments, that we tend to lose focus on the importance of the Hereafter. As an example, someone might postpone performing Hajj if important events related to his career are scheduled to take place at the same time in the calendar.

Allah has next called the life of this world “لَهْوٌ” – a “diversion.” It has the potency to make a person lose focus of the goals of the Hereafter. Imagine a person driving a car; if he or she spots something interesting on the side of the road that will “divert” him or her from driving, he or she will definitely lose focus of the road, resulting in a possible collision.

تَفَاخُرٌ بَيْنَكُم

These words imply boasting to others, and being boasted to, as the above explanation has stated, about intangible assets of prestige and value, such as honorable lineage, awards and achievements, or righteous deeds. Anything that can cause a person to become proud in and of themselves, can be boasted about. It is important to note here, that a person’s intention makes the difference. Several people display their, awards and plaques in their drawing rooms or offices, where they receive guests. This, too, if done to establish one’s credibility in one’s profession, for example, as a practicing doctor whose patients want reassurance that they are coming to a reliable person, would not be blameworthy. However, if it is done to make oneself appear better than others, than it would be تَفَاخُرٌ بَيْنَكُم.

It is interesting how Allah has combined two of the words He has used in this verse of Surah Al-Hadid to describe the life of this world, in another verse in the Quran: the first verse of Surah Al-Takaathur:

أَلْهَاكُمُ التَّكَاثُرُ

“The mutual rivalry for piling up (the good things of this world) diverts you (from the more serious things)“. [102:1]

Since تَّكَاثُرُ means contending to increase in numbers of tangible blessings, it is clear from this verse too, that human beings are “diverted” in this life by this, from their primary goal – which should be success in the Hereafter.

The word زِينَةٌ means beauty and decoration; anything that is instictively pleasing to look at, or beautified to attract our attention. This could include everything that falls under the umbrella of beauty e.g. scenic landscapes, lush vegetation, flowers, and waterfalls, to those things that are made beautiful; which the human heart enjoys.

Bring to mind jewelry, interior decor, architecture, branded/stylish couture, fashion, luxuries, accessories and diverse cuisines. Human beings love to create, experiment and play around with every conceivable kind of raw material provided by Allah, to transform it into something beautiful for their adornment or consumption. Yes, the life of this world definitely revolves a lot around زِينَةٌ !

Allah goes on after this, in the above verse, to elaborate the simile of this world’s life: of it being like the vegetation or herbage that grows on earth, and pleases its tiller/farmer when it reaches its lustrous, colorful peak viz. the plants or crops become strong and fully grown, bearing fruit or grain. However, after a short period of this lustre, color and vibrance, the plants eventually wither, become dry, lifeless straw, and die. The same earth that was alive with crops a while ago becomes empty and plain again; the color, leaves, fruit, grains or flowers are nowhere to be seen, as if they never existed!

That is, in reality, the same thing that happens to everyone and everything during the life of this world. The young, beautiful face becomes wrinkled and haggard; the lustrous hair becomes limp and grey; the strong bones become brittle, and strong muscles give way to weakness; the eyes lose their sight; the erect spine becomes bent. Moreover, every inanimate thing also goes into decline: the architecturally sound mansion becomes depleted and worn over the years, erosion causing its dilapidation and ruin; the clothes lose their newness, shine and glory, withering away; ‘new’ technology loses its value and becomes obsolete and unwanted; the flashy vehicle goes out of vogue and ends up in a junk yard as rubble. The list is endless.

Now that our eyes have been opened to the truth about the life of this world; about how its adornments and distractions are alluring but deceptive in nature, because they divert our attention from the Hereafter and make us think that all this ‘glitter’ will last forever; when in fact, everything on this earth will turn to dust as Allah has promised, we should remember the importance of consistently reciting and reading the Quran as a daily routine, so that we are reminded of this important fact about this transitory life. That way, the reminders such as this verse, that tells us in the end about the two options we have before us – either painful torment, or the forgiveness of Allah and His pleasure – will help keep us focused on those deeds that will enable us to enjoy the truly enjoyable, beautiful, desirable, and eternal life, in shaa’ Allah — the one in the Hereafter.

Please share.

#islam#allah#sunnah#islamquotes#revert islam#hadith#islampost#allahuakbar#muhammad ﷺ#dawah#quoteoftheday#daily life#life quote#life#life quotes#real life#akhirah#dunya#deenoverdunya#deen#ramadan#islamicreminder#islamicquotes#beautiful quote#qur'an#quran#haqq#quranquotes#islamic reminders#islamic books

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary-Hunter McDonnell & Brayden G. King, Order in the Court: How Firm Status and Reputation Shape the Outcomes of Employment Discrimination Suits, 83 Am Sociol Rev 61 (2017)

Abstract

This article explores the mechanisms by which corporate prestige produces distorted legal outcomes. Drawing on social psychological theories of status, we suggest that prestige influences audience evaluations by shaping expectations, and that its effect will differ depending on whether a firm’s blameworthiness has been firmly established. We empirically analyze a unique database of more than 500 employment discrimination suits brought between 1998 and 2008. We find that prestige is associated with a decreased likelihood of being found liable (suggesting a halo effect in assessments of blameworthiness), but with more severe punishments among organizations that are found liable (suggesting a halo tax in administrations of punishment). Our analysis allows us to reconcile two ostensibly contradictory bodies of work on how organizational prestige affects audience evaluations by showing that prestige can be both a benefit and a liability, depending on whether an organization’s blameworthiness has been firmly established.

Much sociological research documents elite corporations’ considerable advantages, including in the policymaking process (Mizruchi 2013; Useem 1984), the creation of market institutions (Fligstein 2008), and the production of culture (Peterson and Anand 2004). Scholars offer numerous explanations for business’s influence, but one common theme is that societal institutions tend to promote business interests due to their social prestige (e.g., Kim 2012; Mizruchi 2004). When firms occupy positions of prominence, individuals act favorably toward them, even when the firms’ behavior would normally elicit negative reactions. In turn, this favorable treatment allows corporations to reproduce their advantages and influence. The tendency toward favorable treatment of prominent businesses mirrors Matthew effect propositions (Merton 1968): an organization’s prestige, including its high status or good reputation, predisposes audiences to view it favorably, especially under conditions when the quality of its behavior is in question (Benjamin and Podolny 1999; Bothner, Podolny, and Smith 2011; Kim and King 2014; Podolny 1994; Sine, Shane, and Di Gregorio 2003; Stuart, Hoang, and Hybels 1999; Thye 2000; Waguespack and Sorenson 2011).

Of course, the advantages the corporate sector enjoys often come at the expense of employees and communities. Theoretically, legal action against corporations, whether civil or criminal, operates as an external constraint on corporate power by punishing businesses that engage in prohibited behaviors. In this way, the law is meant to provide an autonomous means through which society holds business accountable for its actions. However, the legal system’s ability to promote prosocial corporate behavior may be undermined by the Matthew effect, insofar as elite firms are able to garner more favorable outcomes. This possibility is supported by past work finding that elite corporations enjoy considerable influence within the legal domain (Heinz and Laumann 1982; Shaffer 2009), and that litigation generally favors business interests (Brace and Hall 2001; Dunworth and Rogers 1996; Hadfield 2005; Kenworthy, Macaulay, and Rogers 1996). In fact, in one of the earliest sociological treatments of the subject of corporate crime, Sutherland (1949) explicitly warned that status within the business sector distorted the enforcement of laws applied to corporate offenders.

Despite Sutherland’s proposition, the precise mechanisms through which corporate prestige influences judicial outcomes remain unclear. Furthermore, research on corporate litigation has to date “devot[ed] next to no attention to distinctions between litigant types” (Hadfield 2005:1277), which hampers our understanding of why certain corporations seem to receive more favorable treatment than do others (Dunworth and Rogers 1996). The lack of research in this area is surprising, considering the substantial body of work at the individual level devoted to exploring the characteristics associated with sentencing biases. This work provides robust evidence that evaluators respond to the uncertainty and complexity of legal proceedings by searching for salient characteristics of defendants that can be heuristically used to assess blameworthiness. Individual characteristics that prior work has linked to biased outcomes include race, age, gender, socioeconomic status, and perceived character (Albonetti 1998; Nadler and McDonnell 2011; Steffensmeier and Demuth 2006; Steffensmeier, Ulmer, and Kramer 1998). Yet we know little about the characteristics of organizational defendants that produce similarly biased outcomes in legal proceedings. The present article addresses this issue by exploring whether and through what mechanisms corporate prestige operates as a salient organizational characteristic that distorts legal outcomes.

Our exploration of the relationship between corporate prestige and legal outcomes provides an additional opportunity to reconcile two ostensibly contradictory findings about the effects of organizational prestige in evaluative settings. The first, consistent with the Matthew effect proposition, suggests that prestige leads audiences to give organizations the benefit of the doubt in evaluative situations (Davies et al. 2003; Dowling 2002; Fombrun and van Riel 2003). For example, organizational status eases regulators’ concerns when a company experiences product failures (Kim 2012), and investors react less negatively to earnings restatements when a firm belongs to a high-status industry (Sharkey 2014).

Interestingly, a second body of research supports a contrary proposition that prestige can be a liability to firms in evaluative settings, insofar as it can translate into increased scrutiny and harsher reactions from audience members. For example, reputable companies’ actions are more consistently subject to scrutiny from their peers and the media (Edelman 1992; Fombrun 1996; Pollock, Rindova, and Maggitti 2008) as well as agitated stakeholders (Bartley and Child 2014; Briscoe and Safford 2008; King 2008, 2011; King and McDonnell 2015; McDonnell and King 2013). Kovács and Sharkey (2014) found that books that receive prestigious awards are subsequently rated more negatively by users, suggesting that status markers can produce heightened expectations that lead to more negative evaluations (for other examples, see Malmendier and Tate 2009; Rhee and Haunschild 2006).1 In these cases, rather than inducing more favorable evaluations as the Matthew effect would predict, prestige appears to amplify concerns about motives or behavior (Hahl and Zuckerman 2014).

We seek to reconcile these opposing sets of findings by exploring the boundary conditions under which an organization’s prestige might shift from a benefit to a liability in the litigation process. Specifically, we propose that the influence of prestige on legal judgments depends on whether a firm’s blameworthiness for a charged transgression has been firmly established. Drawing on social psychological theories of status (Berger et al. 1977; Correll, Benard, and Paik 2007; Ridgeway 1991; Wagner and Berger 2002), we claim that the mechanism through which prestige influences stakeholder evaluations is elevated expectations (Kim and King 2014). When an organization is initially accused of deviant behavior but its blameworthiness has not yet been firmly established, a positive reputation or high status will lead evaluators to expect that it behaved appropriately. But once an attribution of guilt or blameworthiness has been established, a positive reputation and high status become a liability, as evaluators react harshly to violation of their expectations. Evaluators are more likely to feel betrayed when an organization they trust and admire has deviated, which can elicit an especially punitive response: what we call a halo tax. Accordingly, once an attribution of blameworthiness has been substantiated, we expect evaluators to punish a more prestigious organization more harshly than its peers.

Importantly, in the context of civil litigation, our proposed boundary condition suggests that an organization’s prestige is likely to affect legal outcomes differently at different stages of a lawsuit. In the first phase—the trial—the jury is asked to determine culpability. During this phase, it is uncertain whether the company’s actions merit blame. The aggrieved party will provide evidence to show that the company’s behavior was wrongful or negligent, and the company will offer evidence of its innocence. Under these conditions, we argue that the positive expectations associated with prestige ought to benefit the accused company, creating a halo effect for the accused. Firms that are found blameworthy in the first stage of the lawsuit then move to the second stage: the punitive phase. Here, the company’s blameworthiness has been established with certainty and the jury is asked to determine an appropriate punishment. Under these conditions, the positive expectations associated with prestige have been clearly violated, which we expect will lead to a halo tax in the form of harsher punishments.

We test our hypotheses using a unique archival dataset of jury verdicts from employment discrimination claims filed against a sample of large U.S. companies between 1998 and 2008. We chose employment discrimination as our empirical context because it is a clear example of an organizational transgression, as indicated by highly institutionalized efforts to suppress it, including anti-discrimination laws and ubiquitous sensitivity training programs (Nelson, Berrey, and Nielsen 2008). Legal research documents that employment discrimination lawsuits are especially difficult to win, partly due to biases held by judges and juries (Selmi 2000), which emphasizes the uncertainty of these proceedings.

Ultimately, our results provide evidence for both the halo effect and the halo tax. In our model predicting a jury’s initial assessment of liability, we find that a firm’s status is negatively associated with the likelihood of being deemed blameworthy for employment discrimination. However, in the second stage of litigation, after a company’s blameworthiness has been established, we find that a firm’s status becomes a liability, especially when it is coupled with a good reputation in the domain in which the transgression occurred. We argue that these observed effects can be explained by the benefit (in the former case) and the burden (in the latter) of positive expectations.

Background and Theory Development

Before delving into an analysis of how organizational prestige affects evaluative outcomes, it is necessary to first clarify what we conceptualize as complementary components of prestige: status and reputation (Bitektine 2011; Sorenson 2014). Although they are sometimes used interchangeably (Lang and Lang 1988; Lange, Lee, and Dai 2011; Love and Kraatz 2009; McDonnell and King 2013; Rindova, Williamson, and Petkova 2010; Rindova et al. 2005), status and reputation are different forms of prestige. Status refers to an actor’s “relative social standing” (Sorenson 2014:63) and usually denotes an actor’s position in a hierarchy (Graffin et al. 2013; Podolny 2001) or social rank (Washington and Zajac 2005). Although different sociological literatures vary in their definitions of status, a common theme is an emphasis on a hierarchy that emerges within a group and allows actors with certain status characteristics to obtain greater power and influence (Berger et al. 1977; Correll and Ridgeway 2003). Among organizations, status is often made visible in the form of rankings or patterns of deference that elevate one organization over another (Espeland and Sauder 2007; Podolny 2001).

Reputation, in contrast, refers to shared perceptions of an actor’s unique and distinguishing qualities (Fombrun and Shanley 1990; King and Whetten 2008) and frequently invokes an audience’s perceptions of a firm’s past actions or performance in a particular domain (Fombrun 1996; Roberts and Dowling 2002; Sorenson 2014). Reputation is multidimensional and can be rooted in a variety of different performance criteria (Rao 1994). The same organization can have a positive reputation in one domain, such as product quality, and yet have a weak or negative reputation in another domain, such as treatment of employees.2 In evaluative settings such as legal proceedings, we expect a firm’s reputation in the precise domain in which it is being evaluated will have the strongest effect on outcomes.

Although status and reputation differ conceptually, they are both thought to confer advantages. The benefits that come from being associated with a high-status position are sometimes treated as equal to the positive outcomes associated with having a good reputation. In fact, recent research demonstrates that actors benefit from having both, especially when they are aligned (Kim and King 2014; Stern, Dukerich, and Zajac 2014). Kim and King (2014) argue that the evaluative benefits that come from status and reputation stem from the same underlying mechanisms: behavioral expectations. Status characteristics theory and expectation states theory propose that certain qualities are ascribed with status and subsequently shape expectations associated with actors who have those qualities (Berger et al. 1977; Correll et al. 2007; Ridgeway 1991; Wagner and Berger 2002). Similarly, an actor’s reputation in a particular domain can shape expectations for future performance in that domain (Raub and Weesie 1990). As evidence of this, Kim and King (2014) find that high-status baseball pitchers and pitchers who have reputations for throwing with great accuracy receive more favorable calls from umpires than do low-status pitchers or pitchers who have reputations for being wild and inaccurate.

Lawsuits in the United States provide a natural setting in which to test the effects of reputation and status on audience evaluations. Key to our theory is the notion that these prestige markers ought to matter differently when an actor’s blameworthiness is uncertain versus when it has been clearly established. The U.S. legal system bifurcates a lawsuit into two discrete phases that vary in terms of established blameworthiness. In the next sections, we discuss how the enhanced expectations triggered by organizational prestige are likely to influence audience evaluations within these two separate phases.

The Trial Phase: How Prestige Influences Evaluations Made Under Conditions Where Blameworthiness Has Not Been Established

The positive expectations associated with prestige ought to be especially beneficial when actors face controversial situations for which their level of responsibility is unclear (Lange et al. 2011; McDonnell and King 2013; Rindova, Petkova, and Kotha 2007). For example, some past research finds that audiences are less likely to assign a reputable organization responsibility for a crisis, such as when its products are deemed harmful or dangerous (Fombrun 1996; Klein and Dawar 2004). Other work finds that key external audiences, like the media, are less critical of prestigious organizations implicated in a crisis (Balzer and Sulsky 1992; Coombs 1999; Ulmer 2001). Critical stakeholders like politicians are also less likely to cut ties with high-status organizations accused of bad behavior (McDonnell and Werner 2016).

Reputation and status inform the holistic assessments evaluators make of firms by shaping expectations (O’Donnell and Schultz 2005). Specifically, people tend to infer less blame and responsibility for actors’ bad actions when they have pre-established positive expectations about the actor. This tendency stems from various social psychological theories, including status characteristics and expectation states theories (Berger et al. 1977; Correll and Ridgeway 2003), as well as theories of motivated reasoning (Traut-Mattausch et al. 2004). The former theories propose that an actor’s position in a status hierarchy produces performance expectations, and these expectations lead to reproduction of the hierarchy. The concept of motivated reasoning, in contrast, emphasizes that people tend to interpret evidence presented to them in a way that allows them to confirm their priors (Ditto and Lopez 1992; Kunda 1987). In explorations of motivated reasoning within the context of jury decisions, prior work shows that decision-makers are likely to interpret the evidence presented in a way that confirms their preexisting beliefs derived from racial stereotypes (Rachlinski et al. 2009) or initial impressions of a defendant’s moral character (Nadler and McDonnell 2011).

When the quality or appropriateness of performance is difficult to evaluate, observers will fall back on previously held beliefs and expectations about an actor. In turn, these expectations color observers’ judgments and inferences when they are faced with evidence of a potential organizational transgression, such that the actions of high-status and reputable companies are likely to be interpreted in a more favorable light. For example, one experimental study found that participants evaluating a price increase were more inclined to infer that the action stemmed from a positive and fair motive when the company was reputable, but they tended to infer a negative and unfair motive when the company was less reputable (Campbell 1999). Applied to the context of employment discrimination trials, this research suggests that juries tasked with evaluating a defendant firm’s culpability for employment discrimination are less likely to deem a prestigious organization’s actions as blameworthy. Thus, we expect the following:

Hypothesis 1a: In the first stage of a lawsuit where a company is charged with a transgression, the defendant firm’s status will be negatively associated with its likelihood of being found liable.

Hypothesis 1b: In the first stage of a lawsuit where a company is charged with a transgression, the defendant firm’s reputation will be negatively associated with its likelihood of being found liable.

We also contend that the positive effects of status and reputation on jury evaluations will be greater when the two forms of prestige are aligned. Past research indicates that alignment between status and reputation magnifies the potential for an actor to receive advantages (e.g., Stern et al. 2014). One reason for this is that, as Kim and King (2014) found, status and reputational alignment sharpens behavioral expectations, magnifying innate biases. Another reason is that whereas status is a diffuse signal of prestige and quality, reputation is domain-specific and informs evaluators’ choices about when and how status should influence their judgments. Accordingly, alignment between status and reputation reinforces expectations about a particular kind of behavior, which may be directly relevant to evaluations of blameworthiness for a particular transgression. Thus, if a high-status company is also known for being a good employer, the jury in an employment discrimination lawsuit may believe that the company’s high status is partly a result of being such an outstanding employer, giving the jury more reason to expect the company treats its employees responsibly.

Hypothesis 2: When charged with a transgression, a firm’s status will interact with its domain-specific reputation to negatively affect the likelihood that it will be found liable.

The Punitive Phase: How Prestige Influences Evaluations Made Under Conditions When Blameworthiness Has Been Established

The same positive expectations associated with high status and good reputations can, however, have detrimental effects once an organization’s blameworthiness for a transgression has been established. Prestigious organizations are held to a higher standard precisely because more is expected of them. When it is proven that they have engaged in actions that do not accord with their proffered image, they are more likely to be pegged a hypocrite, provoking a more punitive response from evaluators (Harrison, Ashforth, and Corley 2009).

The scope condition of this halo tax is that an organization’s blameworthiness has previously been established, such that observers have no choice but to revisit and question their prior beliefs and expectations. Evaluators who previously believed that an organization maintained a high standard are motivated to punish the organization for failing to live up to that very standard. Illustrative of this, King and McDonnell (2015) found that organizations with better reputational standing are more likely to be targeted by activist groups when they fail to live up to their reputation. Similarly, Rhee and Haunschild (2006) found that firms with higher reputations for product quality suffer greater market penalties in response to a product recall.

Psychological research on the inclination to punish suggests there is a strong relationship between the anger elicited by an offense and the extent to which people are inclined to punish the offender (Bies 1987; Kahneman, Schkade, and Sunstein 1998). Demonstrating a phenomenon they call “betrayal aversion,” Koehler and Gershoff (2003) found that people recommend more severe punishments when a person or entity they trust behaves in a way that violates their trust. Relatedly, Rosoff (1989) discovered that high-status physicians found guilty of a serious crime were evaluated more negatively than low-status physicians who committed the same crime, and Skolnick and Shaw (1994) found that high-status criminals were judged more harshly when their crime was deemed to be related to their profession.

Extended to the organizational setting, betrayal aversion suggests that the transgressions of high-status or reputable organizations are especially likely to provoke feelings of outrage from their audiences, as audience members may feel duped, jilted, or betrayed given the strong, positive expectations they had for those organizations. This should, in turn, provoke an especially punitive response.

Hypothesis 3a: Once an organization has been found blameworthy for a transgression, higher status will be associated with harsher punishments.

Hypothesis 3b: Once an organization has been found blameworthy for a transgression, more positive reputations in the domain of the transgression will be associated with harsher punishments.

We also expect that the alignment of status and reputation will magnify the harshness of punishment. Inasmuch as alignment sharpens expectations associated with status in a domain-specific area, juries will see employee discrimination by high-status companies that have a reputation for being a good employer as an even greater betrayal.

Hypothesis 4: Among firms found blameworthy for a transgression, a firm’s status will interact with its domain-specific reputation to positively affect the harshness of punishment.

Research Setting

Employment discrimination lawsuits in the United States result when an employee or prior employee of a company alleges that the company treated them adversely (e.g., by firing or refusing to promote them) because of their membership in a protected class. Federally recognized protected classes include those based on gender, age, disability, religion, race, or nationality. This context presents an ideal setting for exploring our theory. The United States has formally prohibited discrimination since the passage of Title VII in the 1964 Civil Rights Act (Sutton et al. 1994), which remains the primary federal cause of action that gives victims of discrimination a right to sue their employer. However, discrimination continues to be a pervasive problem in the U.S. workplace (Edelman 2016); in recent years, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has received nearly 100,000 discrimination charges per annum (USEEOC 2013). Employment discrimination is therefore a clear example of misconduct that is nevertheless common enough to enable empirical investigation.

These cases also represent an ideal opportunity to study how prestige affects organizational punishment because of the manner in which punishment occurs. Organizations found liable for discrimination have to pay a monetary sum to the employee, referred to as the employee’s “damages award.” One portion of that sum, the “compensatory damages award,” is meant to compensate injured parties for the direct financial or emotional harms they suffered as a consequence of the discriminatory action. This aspect of damages is legally limited to the wronged individual’s real or projected losses established in the evidence (e.g., the value of their lost salary), giving the jury little discretion over the awarded amount. However, the jury has more discretion to determine a separate portion of the plaintiff’s damages, the “punitive damages award,” which reflects a sum that the jury can make the corporation pay for purely punitive reasons, meant to demonstrate society’s disapproval of its deviant behavior. The punitive damages award, which can vary extensively from case to case, provides an easily observable and quantifiable proxy for the severity of audience reactions across different cases of deviance. For this reason, punitive damages have been used in other research exploring the mechanisms that affect the severity of punitive responses (e.g., Nordgren and McDonnell 2011).

The structure of employment discrimination suits makes them especially useful for testing our predictions about the disparate role of prestige in attributions of blameworthiness (when there is uncertainty about the firm’s culpability) versus allotments of punishment (when a firm’s deviance has been established). Employment discrimination lawsuits are bifurcated into two discrete phases. The first phase, the trial, determines whether the company is liable, or blameworthy, for a proscribed discriminatory action. Aggrieved employees will provide evidence to show that a company wrongfully discriminated against them, and companies will offer evidence of their innocence. During this first stage, a company’s blameworthiness is uncertain. Some charges of employment discrimination are supported by overwhelming evidence, such that blameworthiness is clearly apparent before a formal declaration by a jury, but such clear-cut cases are unlikely to be in our sample of cases that go to trial and are ultimately decided by a jury. We interviewed a prominent corporate defense attorney who explained this as follows:

There are very high expenses associated with litigating a case through trial, so it is not in the interests of either party to litigate a trial where the outcome of the case is clear. If there is clear and compelling evidence of discrimination, the economic incentives of the defendant are to settle the case, as opposed to waiting for a jury verdict. The cost of a jury verdict is typically greater than a settlement . . . and precedential consequences of having an adverse judgment that could be applied in future cases strongly push companies to not litigate the case if the evidence is clear. So, really, it is only the hard cases that go to trial.

As this quote illustrates, the cases typically litigated before a jury are those for which the outcome is difficult to predict, such that the first stage of a trial is properly characterized as having a considerable degree of uncertainty about whether the defendant company’s actions were in fact deviant.

Firms found liable for discrimination in the first stage of a trial then move on to the second, punitive, stage: the damages phase. At this stage, the court holds a separate proceeding to ascertain the appropriate amount to make the company pay the aggrieved employee. Again, both the employee and the company will present evidence to encourage the jury to award an amount in their favor. But here, the company’s blameworthiness for a deviant action is no longer uncertain because the company has already been found liable. The two stages of a lawsuit thus represent two evaluative settings that vary in terms of whether blameworthiness has been established, providing an ideal context to test our hypotheses.

Past research on corporations and litigation points to numerous advantages that companies have in the process. For one, the “size and complex interrelationships of large corporations make it difficult [for ordinary plaintiffs] to compete with them on an equal basis in investigations and in litigation” (Clinard and Yeager 1980:313). Moreover, because corporations are often “repeat players,” they accumulate more legal expertise and relationships with judges that improve their chances of successfully navigating the litigation process when compared to “one shot” plaintiffs (Galanter 1974). We propose prestige as an additional source of power that corporations uniquely possess over relatively unknown, individual plaintiffs, but we also account for the relative influence of corporate resources and past experience in our analyses.

Methods

Sample Creation

To test our hypotheses, we built a dataset of all employment discrimination cases against any of the 826 unique companies that were surveyed for Fortune’s Most Admirable Companies rankings between 1998 and 2008. The Fortune rankings are regularly used in organizational scholarship as an indicator of a company’s prominence in the corporate field (e.g., Fombrun and Shanley 1990; King 2008; McDonnell and King 2013; Roberts and Dowling 2002; Staw and Epstein 2000). To create the sample each year, Fortune surveyors begin with the Fortune 1,000, from which they select the 10 largest firms (based on asset size) from each industry. They then collect survey data about these firms from industry executives, directors, and security analysts. Fortune aggregates the survey results for each company, then assigns each company a reputation score that ranges from 0 to 10. Fortune ultimately uses this data to create and publish a list of the 50 Most Admired Companies, but our sample includes every company surveyed (including those that were not ultimately selected for the final published list), providing a sample of organizations with a wide variation of scores. By limiting our analysis to companies surveyed for the rankings, we are able to more accurately quantify and compare the relative status of all companies in our analysis. However, this sampling strategy does limit the scope of our findings to firms that are fairly large and visible, which are likely to have the kind of well-established reputations and status orderings that are perceptible to lay audience members. As past research shows, the Fortune ranking has become a commensurable status hierarchy within the corporate realm (Bermiss, Zajac, and King 2014), and maintaining one’s position in the ranking is greatly valued by prestigious firms (McDonnell and King 2013). Thus, the ranking exhibits similar qualities to other status rankings (see Espeland and Sauder 2007).

Having established our sample, we searched the Westlaw jury verdicts database for all employment discrimination cases brought against sampled firms. This database is a comprehensive legal resource that includes a searchable archive with information on the jury verdicts or outcomes of civil (noncriminal) cases brought in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Ultimately, we identified a total of 922 employment discrimination cases brought against companies included in the Fortune rankings that were decided between 1998 and 2008. From these, we culled a subset (n = 176) that settled out of court and never went to trial, as well as a subset (n = 112) that were dismissed by the trial judge for failure to provide a colorable case or for lack of adequate evidence (i.e., dismissal or summary judgment). We ran several robustness checks to ensure that culling of this subset does not introduce selection bias for our ultimate analysis. Unpaired t-tests of means comparing the firms in the top 50 percent of status and domain-specific reputation with the firms in the bottom 50 percent yielded no evidence of significant differences in the incidence of settlement or dismissal between these two groups. Supplemental regressions of the likelihood of settling out of court and of early dismissal also showed no indication of a company’s reputation or status being significantly associated with either outcome.

To focus on cases that were decided by comparable juries, we omit from our analysis a subset of 17 cases that were decided by a judge (i.e., bench trials) or an arbitrator. Additionally, because class action suits, as opposed to suits brought by individuals or small groups, are likely to present idiosyncratic incentives against litigating due to the potentially extreme damages awards they invite when successful, we omit a further four cases that were expressly labeled as class action lawsuits.3

Of the remaining 613 employment discrimination cases in our sample that went to jury, the company was found liable for discrimination in 303 cases and was deemed not blameworthy in 310. Data on incorporated controls were missing for 94 of these firms, reducing our final sample size to 519 cases.

Dependent Variable

In our analysis predicting the outcome of the first stage of employment discrimination suits, we use a binary dependent variable coded “1” if the jury found the company liable and “0” if the company was found not to have engaged in employment discrimination.

For companies found liable of employment discrimination, we capture the extent of punishment through the punitive damages award, a continuous count variable indicating the amount (in dollars) that the company was assessed as punishment for its discriminatory action. A total of 303 cases in our sample resulted in a verdict of liability and produced a damages award. Federal guidelines do not allow punitive damages to be awarded for violations of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA), so we omit 24 cases that rested solely on claims brought under the ADEA. Data on punitive damages were not reported in three cases, and data on incorporated controls were missing for 38 firms, reducing the sample size to 238 cases in models predicting punishment.

Independent Variables

Our measure of organizational status is based on the general score of favorability a firm received in the Fortune Most Admirable Companies rankings. This Most Admired index is a proxy for overall audience assessments, being founded, in part, on surveys capturing industry leaders’ and analysts’ perceptions Each organization included in the list is given a raw score that ranges from 0 to 10. Inherent in this process are comparisons that executives and analysts make between peer firms. Surveyed individuals are asked to rate the 10 largest firms in their industry along various dimensions, allowing Fortune to construct a positional hierarchy of firms within and across industries (for details about the ranking process, see Bermiss et al. 2014). Because the Fortune rankings are collected from surveys administered in the year prior to that in which they are reported, the rankings have a natural one-year lag. We therefore base our status variable on each company’s score in the same year that the verdict in a given case was decided.

We chose to use the Fortune Most Admired rankings to capture status because they (1) are positional, (2) convey relative standing of general favorability to an organization, as opposed to the domain-specific judgment of quality associated with reputation (Rhee and Haunschild 2006; Sorenson 2014), and (3) are available for a large sample of firms across the full panel of our archival analysis. Importantly, we are not arguing that jurors are aware of the Fortune rankings per se, but rather that the Fortune rankings provide a colorable and quantifiable proxy for perceptions of organizational status in the general population from which jurors are drawn (Bermiss et al. 2014). Although the Fortune rankings are constructed from surveys of industry insiders, prior work provides evidence that the rankings reliably align with perceptions held by external audience members. For example, the Fortune rankings predict the willingness of a broad set of actors to associate with a given firm, including audience members within its corporate community, like business partners (Sullivan, Haunschild, and Page 2007), as well those outside its corporate community, like politicians (McDonnell and Werner 2016). Other work demonstrates that a firm’s Fortune ranking predicts how it will respond to social activists and manage its public image in the media (e.g., King 2008; McDonnell and King 2013). These findings suggest that the Fortune rankings accord with a firm’s own beliefs about the general public’s assessment of its status. We acknowledge that the Fortune ranking is an imperfect proxy for specific juries’ assessments of corporate status, and it does introduce potential measurement error. But given that prior research demonstrates that the ranking has validity among activists and other outsiders to the corporate community and maps on to their strategic interactions with companies (e.g., King and McDonnell 2015), we deem it a defensible assumption that the rankings align with jury members’ perceptions of status.

One concern about the Fortune rankings as a proxy for general audience assessments of status is that the measure has been historically dominated by recent performance (Bermiss et al. 2014). This could introduce measurement error in our setting insofar as industry insiders are more likely than the general public to prioritize performance indicators in their assessment of status (Brown and Perry 1994). Substantiating this concern, the raw reputation scores in our sample show strong correlations with firm size and performance. We address this issue by implementing Brown and Perry’s (1994) method for removing the financial performance halo from the Fortune ranking, which involves a two-stage empirical strategy. First, we ran a regression in which we predicted reputation as a function of four indicators of size and performance: liquid assets, Tobin’s Q, total employees, and logged assets. The models show that each of these variables significantly predict Fortune rankings. Next, we computed the residuals from this model, which substantively correspond to that portion of the Fortune ranking that cannot be explained by size and recent performance. We then used these residuals as the measure of status in our models, rather than the raw Fortune ranking.4

In contrast to status, reputation scholars argue that most organizations’ reputations rest on a set of specific practices or characteristics that distinguish them from competitors in a particular domain (e.g., Bitektine 2011; King and Whetten 2008; Lange et al. 2011). We examine the effect of domain-specific reputation by utilizing the annual ratings of firms’ social reputations provided by Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini & Co (KLD) STATS (Statistical Tool for Analysis of Trends). The KLD data draw from diverse sources, including media reports and firm disclosures, to construct yearly numerical ratings of firms’ strengths and weaknesses in seven social domains: community, corporate governance, diversity, employee relations, environment, human rights, and product. Employment discrimination naturally touches on two of the social domains covered in the KLD STATS: diversity and employee relations. To create our proxy for domain-specific reputation, we computed a net composite score of the number of strengths minus the number of concerns in these two areas.5

Like our measure for status, KLD data are an indirect proxy for an individual jury’s perceptions of domain-specific reputation. However, KLD data are a common proxy for reputation in organizational sociology (see, e.g., McDonnell, King, and Soule 2015) that corresponds with perceptions held by outsiders to the corporate community (Werner 2015). Although the precise data collection practices utilized to construct the KLD reputation scores are proprietary, the organization reports that its scores are at least partially constructed using sources readily observable by the average member of the public, including media reports and public criticisms by major NGOs. Thus we deem it a defensible assumption that these scores align broadly with the perceptions of typical jurors. KLD data were only available for around 75 percent of the firms in our full sample, leading to a smaller sample size in models that include our proxy for domain-specific reputation.

Control Variables

We introduce a battery of control variables to account for case-level and firm-level attributes that might influence perceived blameworthiness and punitive responses in the course of a discrimination suit. Among the case attributes that drive outcomes, prior work in criminology suggests that the severity of the defendant’s offense is a primary determinant of the severity of punishment (Steffensmeier, Kramer, and Streifel 1993). The severity of firms’ discriminatory behaviors can vary considerably, and we account for this in several ways in our models. First, we consider the underlying adverse employment actions that allegedly occurred in each case. The summaries of sampled cases in jury reporters provide a detailed breakdown of 25 separate categories of adverse actions, ranging from termination to harassment to a failure to hire. Often several adverse actions are alleged within a single case. We include binary indicators in the models for each of these adverse actions, coding them “1” if a given action is alleged to have taken place in a case, and “0” otherwise.6 A second way we account for offense severity is by controlling for the number of people who were allegedly adversely affected by a discriminatory action, as indicated by the number of plaintiffs in the case.7 Finally, in models predicting punishment, we account for varying offense severity by controlling for the level of harm the victim suffered as a direct result of the discrimination, a sum captured in the compensatory damages portion of the verdict. This portion of a verdict is meant to compensate a plaintiff for losses accrued as a direct result of the discrimination. Compensatory damages may include economic (e.g., lost wages) and non-economic (e.g., emotional pain and suffering) damages. To correct for a pronounced right-skew in these latter two variables, we transformed each by taking its natural log.8

Because different classes of discrimination may elicit different punitive responses from jury members, we include a dummy variable for each federally-recognized protected class on which a discrimination claim is based. These include race or nationality discrimination, gender discrimination, age discrimination, disability discrimination, and religious discrimination. Recognizing that juries’ responses to cases involving different classes of discrimination are likely to vary between communities and over time, we also include a variable, win ratio for similar suits in prior year, that captures the percentage of cases in the same state in the prior year where a company was found liable for the same category of discrimination as a given observation (e.g., religious discrimination, racial discrimination). Additionally, prior research suggests that the victim’s gender may affect punishment. Defendants tend to be punished more severely when they victimize women, who are perceived as more vulnerable (Curry, Lee, and Rodriguez 2004). To control for this possibility, we include a binary variable, female plaintiff, coded “1” if any plaintiff in a case is female, and “0” otherwise.

To protect the anonymity of jurors, information on individual jury members in a case is not publically available. We are accordingly unable to control for the demographic composition of individual juries. Given that jury members are selected from random drawings of local voting populations, we do not expect jury compositions would vary systematically with respect to firm prestige. However, because legal and cultural responses to discrimination may differ by region, we do include fixed effects for the circuit in which each case was brought. We account for potentially meaningful differences in venue in two additional ways. First, federal and state venues can differ in their discrimination statutes, rules of discovery, and standards for summary judgment, each of which could affect case outcomes. We thus include a binary control capturing whether the case was brought in federal, as opposed to state, court. Second, to address the possibility that companies may enjoy a “home field advantage” when they face a jury in their home state, we include a binary variable, home state case, that is coded “1” when the case is in the state where the defendant company is headquartered, and “0” otherwise.

In addition to these case-level controls, we account for several firm-level characteristics that may be associated with legal outcomes. One variable likely to play a central role in attributions of blameworthiness and punishment is the defendant’s prior experience with similar cases. Interestingly, the organizational and criminological literatures suggest two competing mechanisms through which prior experience could influence case outcomes. The organizations literature predicts that prior experience should benefit firms through a “repeat player” effect, whereas the criminology literature suggests that prior experience could provoke a disadvantageous “repeat offender” effect. The repeat player effect, first posited by Galanter (1974), suggests that firms acquire expertise and develop critical relationships over the course of repeated litigation in an area, improving their ability to successfully navigate the complex litigation process. The repeat offender effect, supported by robust evidence in the individual criminal context, suggests that a lengthier record of deviance can disadvantage defendants in the legal process by indicating a pattern of deviance that makes the defendant appear more blameworthy and less capable of rehabilitation (Steffensmeier et al. 1993). To control for the effect of prior experience, we include a variable capturing the total number of times a firm was charged in a discrimination lawsuit in the prior three years.9

To account for each firm’s general size and performance, each of which have been shown to correlate with the commission of proscribed conduct (Clinard and Yeager 1980), we include controls for logged assets and Tobin’s Q. In the organizations literature, Tobin’s Q is a common proxy for market performance that is operationalized as the market value of assets divided by the replacement cost of assets. This variable is superior in this setting to other common metrics for performance (e.g., ROA), because it is less susceptible to managerial manipulation, which is common during periods of social scrutiny (McDonnell et al. 2015; Watts and Zimmerman 1986). To account for variance in the available resources that firms can devote to their defense, we include a control for the total amount of a firm’s cash stores. Given that firms are naturally more likely to be accused of employment discrimination when they employ more people, we also control for each firm’s number of employees.

We account for potential temporal factors that might affect jury outcomes through fixed effects for the year in which each verdict was decided. Finally, to address the possibility that jury members may have different expectations and responses to discrimination committed by companies in different industries, we include fixed effects for each company’s major SIC industry division (i.e., two-digit SIC code), as reported in Compustat. Table 1 provides summary statistics and correlations of these variables.

Table 1. Summary Statistics and Correlation Matrix

Model Specification

We test Hypotheses 1 and 2 using a probit model that predicts the likelihood a firm charged with employment discrimination is found liable. The probit regression is appropriate for models with a binary dependent variable. Every case that went to jury was included in this first stage.

The models testing Hypotheses 3 and 4 include only firms that have been deemed blameworthy for employment discrimination, as only firms found liable will go on to be assigned a punishment by the court. Our dependent variable, punitive damages, is a highly overdispersed count variable, so we use a generalized linear model with negative binomial errors and a log-link function, using the glm command in Stata. One common way to correct for potential bias in a skewed count dependent variable is by log-transforming it and then running an OLS regression. The alternative we use, a log-link function in a generalized linear model, has the advantage of returning predictions directly on the dependent variable’s original measured scale, negating the need for back-transformation and simplifying interpretation (Cox et al. 2008; McDonnell and Werner 2016).

We expect that results within a state are more likely to be correlated than those between states due to localized laws as well as potential regional differences in attitudes toward discrimination. Additionally, our data include multiple within-firm observations, which are also likely correlated with one another. Accordingly, we cluster standard errors at both the state and firm levels. All models were run using Stata 14.0.

Results

Results from the models predicting the likelihood that a company charged with employment discrimination was found liable are shown in Table 2. Model 1 includes only the control variables. The models provide mixed evidence that larger firms (in terms of number of employees) are less likely to be found liable than smaller firms. Models 1 and 2 provide additional suggestive evidence that firms do enjoy a home court advantage, as firms are significantly less likely to be found liable when a case is brought in the state in which they are headquartered.

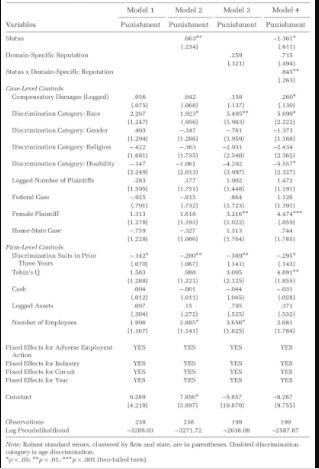

Table 2. Probit Regression Predicting the Likelihood of Being Found Liable in Cases of Alleged Employment Discrimination, 1998 to 2008

Model 2 introduces our measure of status to test Hypothesis 1a. In support of this hypothesis, the model demonstrates a statistically significant and negative relationship between a firm’s status and its likelihood of being found liable for employment discrimination. Post-estimation margins analysis of Model 2 indicates that firms with a status score one standard deviation above the mean are around 14 percent less likely to be found liable in a discrimination trial than are firms with a status score one standard deviation below the mean.

Model 3 of Table 2 introduces the proxy for domain-specific reputation to test Hypothesis 1b. This hypothesis is not supported, as the model provides no evidence that a company’s reputation, as indicated by its net KLD score for employee relations and diversity, is related to the likelihood of liability. Model 4 of Table 2 tests Hypothesis 2 by including an interaction of status and domain-specific reputation. Again, we find no support for the hypothesized effect. Taken as a whole, these results suggest that holistic, generalized signals of prestige, such as status, may carry more weight for evaluations of corporate conduct in ambiguous situations than do more applied indicators of prestige, like domain-specific reputations.

Table 3 shows models predicting the extent of punishment through assessed punitive damages. These models yield several interesting results for control variables that warrant mentioning. First, across all models we find that past involvement in discrimination suits appears to broadly benefit a defendant firm, as the number of past discrimination suits a firm has faced is negatively related to the level of punitive damages a liable firm is assessed. This finding supports Galanter’s (1974) notion that firms are advantaged by being repeat players in the legal system: past experience confers enhanced capabilities for achieving more favorable outcomes in future suits. This also highlights that punitive processes are distinct for organizations and individuals, given that the latter tend to be punished more harshly when they have prior charges on their record that mark them as “repeat offenders.” Because the offensive actions at issue in discrimination cases are normally undertaken by different deviant individuals within a firm, juries might not perceive firm-level offenses as contributing to an aggregated “record” in the same way as they accumulate for individuals. This may be remiss, as some scholars argue that corporate recidivism signals a firm-level problem, suggesting “a corporate atmosphere favorable to unethical and illegal behavior” (Clinard and Yeager 1980:117).

Table 3. Generalized Linear Models Predicting Punitive Damages Levied Against Companies Found Liable for Employment Discrimination, 1998 to 2008

Results for the other control variables vary markedly across the models and should be interpreted with caution. Here we discuss only the variables that show a significant association with punishment in the final model (Model 4 in Table 3), which incorporates all hypothesized effects. This model suggests that cases alleging racial discrimination, as compared to age discrimination, draw significantly more punitive damages, whereas those alleging disability discrimination yield significantly smaller awards. Cases that produced more costly harm—indicated by greater compensatory damages—draw significantly larger awards, supporting the notion that discriminatory actions that caused more harm are punished more aggressively. The significant effect of the female plaintiff variable suggests that juries may be more punitive when at least one of the victims of discrimination is female. This finding complements criminological work that shows violent crimes with female victims are sentenced more stringently (Curry et al. 2004). Finally, the significant effect of Tobin’s Q suggests that better-performing firms may be punished more harshly for transgressions. Predicted values from the final model suggest that a firm with performance one standard deviation below the mean would pay around $23,000 in punitive damages, whereas a firm with performance one standard deviation above the mean would pay over 20 times more: $470,000. One possible explanation for this is that outperformance might carry a connotation of corruption or injustice when it is won during periods of objectionable conduct. This resonates with the more general claim that stakeholders respond negatively to outperformance that appears to have been achieved through illicit means (Harris and Bromiley 2007; Mishina et al. 2010).

Model 2 in Table 3 introduces the proxy for status. In this second stage of litigation—once an organization’s culpability has been established—we find that organizational status becomes a liability, in support of Hypothesis 3a. Notably, the effect of status on punitive damages is net of the effects of firm size and profitability. Post-estimation margins analysis of Model 2 indicates that a firm with status one standard deviation below the mean would pay a predicted value of $183,143 in punitive damages, whereas a firm with status one standard deviation above the mean would pay $674,860.

Model 3 in Table 3 introduces the proxy for domain-specific reputation. This model produces no evidence of reputation having a significant independent effect. Hypothesis 3b is thus not supported. The interaction of status and domain-specific reputation in Model 4 is statistically significant, suggesting initial support for Hypothesis 4. However, interaction terms in a nonlinear model must be interpreted with caution (Ai and Norton 2003; Mood 2010), and post-estimation margins analysis of this model yielded no evidence that the interaction produces a significant effect at any particular point in the observed distribution of our data. Given this mixed evidence, we explore the interaction effect in more detail through a battery of additional models (see the online supplement). As a key robustness check, we replicate the interaction effect in a linear model (an OLS regression with a logged dependent variable), which allows for a more straightforward interpretation. In the linear model, the interaction term remains statistically significant and positive. This evidence provides clearer support for Hypothesis 4, insofar as it demonstrates that the interaction has a significant average effect across the full distribution of status and reputation. However, we are unable to identify exactly where in the distribution the effect is driven. Future work is needed to more precisely illustrate the moderating role that reputation (and the associated mechanism of hypocrisy) plays in driving the halo tax.

We ran a number of additional alternative models to probe the robustness of our findings. First, we acknowledge the potential for selection bias to affect our results, as only the firms found liable for employment discrimination are selected into the second stage of a lawsuit and assigned punishment. To mitigate concerns about selection bias, we replicated our models as a two-stage Heckman selection model. In this estimation, the probit regression predicting liability is used as a first-stage model to estimate a selection effect coefficient (referred to as the inverse Mills coefficient, or λ) that is included as a control in the second-stage model predicting punishment. We use the win ratio for similar suits in prior year variable (described earlier) as a selection instrument. Supporting its efficacy as a selection instrument, this variable is highly correlated with a firm’s likelihood of being found liable for employment discrimination, but it is not significantly associated with punishment levels or the underlying error term of the second-stage model. Results for all key variables are substantively identical in these models. Furthermore, the lambda coefficient in the second-stage model does not approach statistical significance, which suggests that selection is not a serious concern in this context.