#mother of all orishas

Text

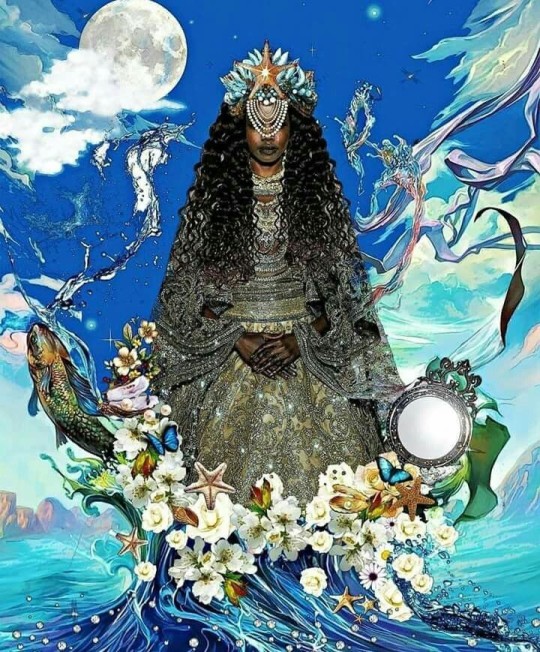

iemanjá (yemoja) by Bukuritós Aruanda

"Yemọja is a major water spirit from the Yoruba religion. She is the mother of all Orishas. She is an orisha, in this case patron spirit of rivers, particularly the Ogun River in Nigeria, and oceans in Cuban and Brazilian orisa religions." Wikipedia

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iemanjá (also spelled Yemayá. Yemoja, Iemoja, or Yemaya) is one of the most powerful orishas. She is the mother of all living things, rules over motherhood and owns all the waters of the Earth. She gave birth to the stars, the moon, the sun and most of the orishas. Yemaya makes her residence in life-giving portion of the ocean (although some of her roads can be found in lagoons or lakes in the forest). Yemaya’s aché is nurturing, protective and fruitful. Yemaya is just as much a loving mother orisha as she is a fierce warrior that kills anyone who threatens her children.

Yemaya can be found in all the waters of the world, and because of this she has many aspects of “caminos” (roads), each reflecting the nature of different bodies of water. She, like Oshún, carries all of the experiences of womanhood within her caminos. Contrary to popular belief she is not just a loving mother. Some of Yemaya’s caminos are fierce warriors who fight with sabers or machetes and bathe in the blood of fallen enemies. Other roads are masterful diviners that have been through marriage, divorce and back again. Some roads of Yemaya have been rape survivors, while other roads betrayed her sisters out of jealousy and spite. No matter what camino of Yemaya, all are powerful female orishas and fiercely protective mothers.

Yemaya has a very special relationship with two orishas in particular: Oshún and Chango. Oshún is often depicted as Yemaya’s sister, and Yemaya allows Oshún to take residence in her rivers. Yemaya and Oshun relate to one another like typical sisters; they love each other and also have a bit of sibling rivalry. Chango and Yemaya are inseparable. Some followers of Santeria say Yemaya is Chango’s mother. The two of them eat together and Chango shares his wealth with Yemaya. Yemaya helped mold Chango into the wise leader he was meant to be from birth (although he initially lacked the skill to rule with grace).

You can find me at: Instagram / Pinterest / Marketplace

#Iemanjá#iemanja#yemayá#yemanjá#umbanda#candomblé#santeria#artists on tumblr#black art#black tumblr#orishas#orixás#shango#xangô#oxum#osun#osùn#support black creators#support black business#support black people#odoyá#encontro ancestral

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

Little detail I love in The Raven King:

The statues of the Yoruba orishas (goddesses) in the 300 Fox Way scrying sessions.

Calla's statue of Oya, who is considered the orisha of wind, lightning and storms, as well as being associated with change, transformation and destruction.

Maura's statue of Oshun, who is associated with love, fertility, water, purity and sensuality, and possesses the human qualities of spite, jealousy and vanity.

And Persephone's statue of Yemaya, orisha of motherhood and the sea. She's considered the great mother of all of us, representing Mother Earth, the life giver.

I don't know much further than this, and I might be wrong about a lot of it, no disrespect intended to the Yoruba religion.

But I really love how it sort of ties into the women of 300 Fox Way??? Like Oya being orisha of storms, and Calla being a storm contained inside a woman, and Oshun, the orisha of love and fertility, like Maura, who has found love and has a family of her own, and the shared trait with her and her daughter of vanity, jealousy and spite. And Yemaya, the motherhood orisha, and Persephone, who was not a mother, but she was a teacher, a carer. She took care of Adam, taught him to regain control over his own life, taking care of Blue and Maura and Calla.

Anyways :))

#the raven cycle#maggie stiefvater#trc#the raven boys#the dream thieves#blue lily lily blue#the raven king#maura sargent#calla johnson#persephone poldma#300 fox way women have my heart in a chokehold#300 fox way

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lost Girl: Chapter 1

chapter list 🧣 next chapter 🧣 AO3

As a child, I loved the stories my father would tell.

They were best told after a long day of work and your hands were raw and the calluses on your feet had calluses. Our tribe had always been hunting people, he saw no reason to stop the traditions of the Nwabu with me. So at 6 I was given a rifle and taught to hunt deer and fowl, waiting hours on end until the opportunity finally struck. Tiring as it was, the stories at the end of the day somehow always made it seem worth it.

I loved the ones that had to do with my mother the most, rare as they were to hear. My memories of her were hazy; at most I remembered the faint sound of her humming as she held me close to her chest. She passed away when I was three, illness claiming her before we moved away deeper into the mountains. At least that's what my father told me. He didn't like talking about her and even as a kid, I felt that if I mentioned her, he would break. So I made it a habit not to talk about her unless he brought her up first.

Otherwise, the stories my father would tell always had to do with the orishaー the gods our people worshipped before they came to the Walls to escape the Titans. A lot of them had been forgotten, lost over the generations as our kind's numbers dwindled. The ones he did remember, my father made sure to tell me about.

Oshun who blessed my mother with boundless beauty.

Erinle who guides us while we hunt.

Oko who we thank for the food the earth provides.

I listened to every word as if honey dripped from my father's lips as he told me tale after tale about beings most of the Walls' inhabitants never even knew about. Instead they worshipped the gods that created the Walls we lived in, Maria, Rose and Sina.

"Then why don't we worship them when we live in the Walls they made?" I asked after learning of the three deities.

"Because they aren't our gods," he answered smoothly, as if he knew that question was coming.

I cocked my head to the side, "we can still be friends with their people even if we don't believe the same thing?"

That question made my father's nostrils flare. "Those people aren't our friends," Ba snapped almost immediately. My heart lurched then, fearful I made my father angry, or worse, disappointed in me. "We stick to our own and interact with the pale ones when we have to."

"... are we supposed to be afraid of them?" I asked quietly when I found my voice.

My father didn't answer my question immediately, dark brown eyes lost in thought as he stared into the flames. "A long, long time ago there were many kinds of people. That changed when the Titans came," Titans. Again, that word. I'd never seen one in all my young years of living, neither had my father. I couldn't even begin to imagine what these monstrous beings were supposed to look like. They were big, larger than the trees that surrounded our home. Still, it was hard to imagine something I'd never seen even if they were supposedly the cause of humanity's decline. "When the Titans came and began eating everyone, many kinds of people went extinct. Other tribes, other types of people besides our own. We're the descendants of the lucky ones who made it, but they couldn't have predicted the problems that came after. The pale ones don't think of us as the same even though we're humans hiding from the Titans like them.

"To them we're slaves for labor. Dirty people. Our men are worked until death in unsavory places and our women..." Ba trailed off. "Our people are dying." My father eyed my hair. For as long as I could remember, he kept it short and as close to cleanly shaven as possible. He said he wanted me to be tough, like a boy. He said it was to protect me from the pale ones. Back then, I just felt that my father wanted a son and he was compensating for it because he got saddled with me instead. " We're the last of our tribe, [First], probably even the last of our kind in these damned Walls. We don't live, we survive."

The quiet of the house felt eerie and it scared me. "I sometimes wonder if they had known this was the fate that waited for us, would they still have believed it was better than being put in the bellies of monsters."

"... Ba?"

My father sighed, pinching the bridge of his nose before patting my head. "No more stories tonight, [First]," he whispered solemnly. "It's time for bed now."

"I'll be gone a couple of days, [First]."

"I know, Ba," you curl into a tighter ball, heart beat roaring in your ears. I still can't believe I'm doing this, one half of youー likely the sane halfー murmurs nervously. The other half of you shakes your head. I've already committed to this. I'm doing this! You knew as you lay in her your, ankle throbbing lightly, it is too late to turn back now.

"I really don't feel comfortable leaving you that long on your own," even without seeing him, Ba still sounds doubtful despite your nonchalant reply.

You feel your stomach lurch. Just go already, Ba! This is truly it, you know. You want so badly to just sit up and run, feeling the wind run over your head and not look back over your shoulder at your father who would be undoubtedly furious. Instead, you sit up up slowly before looking at him and blinking as groggily as you can. "Ba, you said we're low on food, I'll be fine here on my own. You really need to go hunting."

Ba nods taking heavy steps to her bed. "The hunting is always best when we're together." He says, reaching over to squeeze your left ankle gently. You wince and recoil. Even if your hurt ankle had been planned, it didn't mean it still isn't hurting. The injury in its entirety is superficial but the pain is still vaguely there. Nothing to keep you from walking, but as far as your father knew, your injury made you immobile for the next few days. "You promise me that you remember to stay inside, there's enough food for you to take care of yourself."

"Yes, Ba," you nods. How your excitement hasn't shown yet, you are unsure but thankful. If Ba knew of your plans you doubt you'd ever be left alone again.

"Don't answer the door for anyone if they knock," he continues in a more grave tone.

"I know, Ba," you repeats, exasperation barely hidden in your tone. Why Ba insisted on repeating his many rules you know inside and out already, you don't know. He'll stop with the rules once I prove to him I can take care of myself and there's nothing to be afraid of anymore.

"Hide immediately, don't let anyone see you. And make sure-"

"To always keep the curtains closedー I know, I know!"

Ba's expression is sharp and unrelenting like the earth itself, "I know it seems like a lot, [First], but it's all to protect us. To protect you. Your mother-" Would feel like you're driving her crazy too. You keeps the disagreeable remark to yourself, lest your father abandon his hunting trip altogether to re-educate you about your ancestors. How when the Titans first arrived, your tribe had been among the few to find refuge within the three Walls protecting them from the giant monsters roaming the world. "would agree too. Humans like us," Ba gestures to your matching brown skin. "you don't find many of. We might even be the last ones. There are many who would want to steal those like us away."

You barely stop yourself from rolling your eyes, the story hadn't changed since you were 6. The same one every year, and every year nothing happens. The few times you had ever gone to into town with your father, nothing ever happened. You took the furs and hides you tanned to the city, sold them and then went right back home as always. The rules then are strict as the ones you hear everyday for the house. Stay by Ba's side and don't talk to anyone, not even the kids that always stopped and gawked at the two of them as they walked.

"They only stare because they've never seen people like us," Ba had said when you begged him to let you play while he conducted his business. "They don't care about actually knowing us." You remember going to sleep bitterly that night. Even now you are doubtful of his claims. Ba might be smart but he can't know everything. Maybe they did want to know us, want to know me.

"These rules might seem strict, but it keeps the two of us safe," Ba says yet again. You huffs quietly but otherwise keep your mouth shut. You knew that day there is no point in trying to get your father to change without any sort of proof to get him to. Ba sighs, rubbing his hand across your head. Maybe he knew there is no point in arguing further either. "I'll be going now, remember everything I said. I'll be gone only a couple of days, you have the rifle if anything goes wrong." But nothing should. "The ones that barge in here aren't people, they're predators. Protect yourself if it becomes necessary." With that, Uba stood up and left your room.

It's only when you're sure an hour has past and that your father is most certainly gone did you finally toss off your blankets. Your hands shake in excitement and anxiety. You have only two days days, maybe three at most, to make good on your plan to put as much distance as possible between yourself and your home. Ba would be heading east down the mountains and you know his routine by heart after the many times you had left with him on these expeditions. Ba wouldn't turn you home until you had as many as two deer with a few ducks to spare. The ducks would be plucked raw, feathers washed and used for pillows. The deer would be skinned and most of the meat would be hung to dry. If Ba was really lucky, he might catch a wild hog. Erinle willing, the prey would be bountiful this season before the rain would arrive. Wonderful that would be for your belly, you also knew your chances of leaving would be completely diminished. You have to leave now when Ba's hunting trip is too important for him to skip.

Guilt hummed beneath your skin all-the-while as you rummage through the kitchen for loaves of bread. You won't take more than what you will need. Even with what you takes, there is still plenty of yeast for Uba to make even more bread for himself and he'd have plenty of meat coming back from his trip.

Ba can't keep me hidden here forever. You nod with determination, willing the guilt to leave you. There is nothing to be guilty of when this is for the better for both of their lives. Ba is heading east and you are heading west. There's no opportunity for you to accidentally cross paths. From the map in Ba's study, Leipmold is the closest town from where there home is located. You had traced it over many of time on your own parchment. You had always been indifferent to hunting, but now you appreciate the knowledge. You can hide your own tracks and hunt for your own food, then you would sell any furs you could skin herself in the markets and make money. Only once you are satisfied would you go back home.

Ba would be mad that you took off on your own, but you hope that with enough coin, his parental wrath could be assuaged.

I'll sell rabbit fur! There should be plenty hopping around. You stuff your blanket into your knapsack. Nothing'll change if I just do what he tells me all the time. Ba never talks about the day you'd be a grown up and forced to live on your own. You doubt he has even imagined a future like that, but you do. One day, you would live in town. You'd make friends with the city folk, unafraid and without hesitation. You wouldn't have to shave your head and you would be able to wear whatever clothes you desired. You've never been allowed to wear dresses. Ba said the pale-skinned humans would sell you off to do the unthinkable if they knew you were a girl, whatever that meant.

If Ma was still alive that she'd have let me wear dresses the color of the sky at dawn and let my hair grow as much as I want. A prickle of anger surges through you before you shake it away. You don't have to be upset anymore when you can grow your hair out in the city and buy whatever clothes you wants. Then when Ba realizes he has nothing to worry about, he will let you do as she pleases.

With that, you sling your rifle over your shoulder and packs the few bullets Uba had spared in your knapsack. In its place, you leaves a note.

Ba, I've gone to Eppelbog. I know you think that I'm just a kid, but I'm 10 years old. I'm going to sell our furs there and come back with money. Just wait here for me, okay? Eppelbog was south from their home according to Ba's map and nowhere near Leipmold. If Ba decides to track you down in his worry, his heading there first would give you plenty of time to get to Leipmold before he realizes that he's been duped.

Heaving a deep breath, you open the door.

Ba is gonna be gone for at least 3 days if I'm lucky. You relish the sound of the grass crunching beneath your feet and hope Ba didn't suddenly realize he had forgotten something. If he did, your journey would end before it truly had a chance to start. There's another mountain path I can take between here and Leipmold and I can get to it by tomorrow morning. Traveling through the mountain chains will be your best chance at throwing off Uba if he decided to track you when he realized you were gone.

You had two and a half loaves of bread, around five bullets and a wineskin full of the freshwater you could spare without taking too much from your father. This should be able to last until I get to Leipmold. Any rabbits you caught could be cooked completely, saving half the meat for the next day to stretch it out, something you and Ba would do plenty of times with your food. I'll be there before I know it, you purse your lips. On the map it didn't look that far away. I might even get there by tomorrow night!

Yet Leipmold doesn't come tomorrow night, nor does it come the night after next.

All that comes is disappointment, hunger and the fear that Ba's map wasn't a true representation of the distance between cities.

Your stomach growls but you refuse to stop and eat when the food you have needs to be saved. It's really bad about that goose. You had seen one yesterday, but by the time your rifle was ready, it had flown beyond the opening of the trees and the hunger pangs kept you up most of the night. Today will be different, you swear. You will catch something. The path you've been walking surely will end soon enough and you'd finally be close to your journey's end. The prey will be bountiful as well. Maybe there you will even find some berries or mushrooms to eat as there had been none to find so far on your trail.

Maybe I should have grabbed some of the meat they still had before Ba's hunting trip, after all. Ba would be coming back with plenty of food for himself, he wouldn't have notice the leftover venison missing.

With a sigh, you put her traced map back in your bag and stand on her feet, wincing at the aching sensation. Soon you'll be at the base of the mountain, you remind herself. There will be less undergrowth hiding food and there'll be berries and mushrooms that aren't poisonous. It'll definitely be easier finding rabbit burrows without all the shrubs. The path east that you and Ba took for hunting always seemed clear and kept in comparison to this wild path. Maybe Ba had been clearing it himself to make it easier to hunt. Mohammed at least wishes there would be a snake slithering along bushes, it tastes pretty nice all things considered.

Your stomach rumbles again. No more thinking about food, you groan.

It's then that you smell apples and you stop in your tracks.

As the smell continues to waft through the air, you lick your cracked lips. Apples were a rare treat back home. Ba had planted a few seeds on your land but your trees seldom had a good harvest making you treasure them whenever you could manage to grow a good few. I just wanna see where it's coming from. Suddenly your aching feet are easier to ignore, mouth watering the closer and closer you get to the source of the smell.

It doesn't take long for a small cottage to be seen through the trees. The back door wide open and from where you stand, you can see an open window with a pie sitting in the sill.

Who on earth leaves a perfectly good pie unattended?

Your stomach growls something fierce and you grabs it. I should just go. Hungry as she rea, you will be cursed if you steal from someone.

But no one is even here, the hungry part of you argues. If the pie is that important, the window and door would be both be shut and you wouldn't have smelled the pie to begin with. You lick her lips again but they somehow feel even drier. You look like a fox stuck in a trap, starving, with its own paw starting to look delicious after days of not eating. When your stomach rumbles again, your resolve solidifies. The gods might be upset you stole a pie, but your mother would be more upset if her daughter joins her in the heavens because you starved to death. You drop your bag and rifle behind a bush and stumble out of the brush, your pant leg catching on a few brambles.

You'd eat as much as you can before running away, that will hold you off the rest of the day if you ate half. Maybe you can fold the tin over afterwards and carry it back to your bag to eat the second half tomorrow. Two days worth of food, your mouth waters at the thought. This meal could be two days worth of food!

You rush up the few porch steps leading into the house, weary of the creaking of your boots on the floorboard as you search for the kitchen. It's a boon that the cottage isn't too big, you passed by two rooms in the hall that eventually led to the kitchen and dining room area. The last door, you assume is the front door. Even better is if the family is in front doing something else, distracted for long enough for you to leave without much of a trace. I'm sorry, I'm really sorry, but sorry will likely mean nothing to the family you are stealing from. If I come back home this way after Leipmold, I'll pay them back for the pie. I'll bring them a basket of apples so they can make another one!

You stand on a conveniently placed stool beside the counter and grab the pie with ease, reaching for a spoon in the sink that looked like it had been rinsed off recently and, guilt and all, digs right in.

It's on your third spoonful that you hear a soft gasp and freeze. Don't look, they aren't there if I don't look. Still, even at 10 you know that isn't how the world works. You spin around quickly, neck nearly cracking in the process as you see the girl standing behind you with her mouth agape. She's pretty, you think without trying. The girl's hair is long and black with dark eyes that almost matches. She also sees that the pie her mother probably worked on is now ruined.

You ignore how your hands burn when you pick up the pie tin and make a mad dash to the backdoor.

At that, the girl finally breaks out of her stupor. "W-wait!" She cries, storming after you. "Stop, you pie thief!"

"Mikasa?" The voice of a woman approaches closer and you feel like crying. "What's going on?! Are you alright?!"

"Some boy is stealing our pie, Mom!"

When the steps leading to the back door came into view, you prepare yourself to jump over them. You'll just have to hide under a shrub until they give up their search outright before you can grab her rifle and knapsack. That was the plan at least before a third person arrives, a tall man with blond hair appears. The way he's holding his arms out wide to prevent your exit that makes you skid to a halt in surprise before stumbling forward clumsily and crashing on the floorboard. You wince as your chin hits the floorboard and your teeth clash together.

"Oh no!" The young girl's disappointment is palpable. The pie tin had landed upside down in a sticky mess. "Mom, your pie..."

You groan and clasps your jaw. You struggles to sit yourself back up, your vision is cloudy from the hot tears welling in your eyes. "Ow ow..." You garble, it didn't feel like anything is broken but that didn't make it hurt any less. You sniff harshly, trying to blink your eyes into being dry. You don't want to cry in front of these people. Not when you know it's your fault you ended up like this.

The gods really have cursed you for stealing the pie.

Anxiously, Mikasa peers through the crack of the door.

Her mother and father had told her to stay in the kitchen after they had caught the boy trying to steal their pie, but she is still worried. Mikasa feels disappointment and anger swirling in her equally as she looks at the boy, brown hand clutching his chin. Sunny days seldom result in her having ample time with her parents and yet her mother made that seldom into definite that morning when she asked Mikasa to help her bake. It was her first experience baking and to see it stolen so callously and then spilled onto the floor dampered her spirit.

Now she watches in private, wondering what her parents will do next.

Your eyes suddenly catch gray and Mikasa ducks with a flinch to avoid the boy noticing her.

Why'd you hide? Mikasa scolds herself. He's the stranger here, you don't have to hide! Despite her self-scolding, Mikasa doesn't feel brave enough to look up again, fearing she'd be spotted again instantly. She places a small hand over her chest, hoping it will calm her heartbeat.

"I'm sorry about your pie," the boy's voice is barely audible from where Mikasa crouches. "I shouldn't have tried to steal it. I don't have any apples to give back right now. Please don't be mad."

"Where is your family?" Mother doesn't sound angry, so much as she sounds concerned. Like when she thought Mikasa had gone too far into the forest to play. She is always worrying about something, Mikasa's mother believes it is justifiable, however. In the forest they lived, there are wild animals and too many trees for Mikasa to get lost in. "What's a child as young as yourself doing alone in these mountains?" Her voice was gentle.

"Ba went to Eppelbog." The boy answers after a few seconds. "He wanted me to go to the Leipmold to sell furs."

"'Ba'?" Mother repeats, sounding as confused as Mikasa is. She never heard that word before. "Is that your father?"

"Yes, ma'am."

Father sounds surprised, "your father decided to send you on your own to Leipmold? That's at least two weeks away from here on foot! How old are you?"

"10," a year older than Mikasa's 9 and he looks so different from her and her parents. The boy taller than her and his eyes were a bright [color] with skin that is the color of Ms. Penny's feathers, their oldest hen who died the previous winter. Mikasa feels her courage return enough to attempt her peeking once again. She's never seen anyone with skin that dark before.

"10?" Mother brings a hand to her mouth in disbelief. "Who sends their 10 year old to sell furs that far away?"

Father glances at Mother with a reproachful look, "that isn't too young an age for some families to have their boys work, Shiori."

"13 is one thing," Mother argues, crossing her arms adamantly. "10 is another, Mikasa's only 9! He needs to be home with his mother, Abelard."

"Don't have one," the boy shakes his head nervously. "Ma's gone, been gone since I was three. It's just me and Ba now."

Mikasa eyes widened with a shudder of horror. His mother is gone? She looks at her own parents, unable to imagine a reality in which either of them weren't with her everyday. No longer seeing her mother's embroidery or welcoming her father home after he was gone for a few hours of hunting, bringing back something that would make her heart jump as she tried suppressing the vague feeling of fear witnessing it.

"Is this your first time going to Leipmold on your own?" Father asks the boy who then nods in agreement. "Your father was irresponsible to send you on your way without enough food to last you an entire trip. You're going on foot the entire way?"

"I was supposed to catch rabbits on the way, I thought I could eat them on the way." The boy explains before wincing briefly. He rubs his chin again tenderly, the fall from earlier clearly taking a large toll on him. "There weren't a lot of rabbits though. I thought Leipmold was closer on the map my dad had in his study."

At that, Mother and Father both exchange a look that Mikasa didn't understand. Neither did the boy it seems as his expression is one of worry as he looks between the two of them. "Please don't tell him about the pie, he'll be mad," he begs.

"We'll keep the pie to ourselves if you answer some more of our questions," Father reassurs him with a smile. "When is your dad going to return home?"

"A few weeks," The boy's answer is slightly muffled. "He has a lot to sell."

"And you're absolutely sure he'll come no sooner than that?"

The boy nods again.

"What's your name?"

The boy hesitates at that, looking elsewhere. Mikasa is prepared to duck again if he's going to look in her direction again. "It's alright, dear." Mother's voice is soothing as she speaks and Mikasa can see she is smiling softly. "You can trust us."

"... [First]," the boy said after another moment passed. "[First] [Last]."

"[First]." Mikasa's mother repeats, copying the syllables slowly. "That's a lovely name, did your mother pick it?"

"Ba did."

"Well at least your father had good sense to pick a decent name." Mother murmurs to herself. Mikasa wonders if her upset towards the boy's father would last until she met him. Mikasa has never even been to Shiganshina, south of their home in the mountains which is an intimidating enough thought. Traveling alone in the mountains seems even scarier. She wonders if that's why the boy ended up eating their pie. "How about this, instead of going to Leipmold, you work here for us for a few weeks while your father is in Eppelbog and we pay you for it? Then you can leave for home from here and we won't even have to mention the pie."

[First] blinks and pulls away from his hand in his surprise. "Really?"

Mother and Father nod in unison. "It would be a lot safer for you to do this instead, I think your father would understand," Father beams with his hands on his hips.

"The mountains are no place for a child to be traveling on their own," Mother continues sounding resolute. "We'll have no problems letting you stay here in exchange for help with the chores around here. And you'll have to get along with our daughter, of course," Mikasa bites her lip and had to stop herself just barely from shuffling her feet. "She can be a bit shy, so you'll have to be patient with her."

"I- um-"

When Mother claps her hands together, Mikasa knows there will be no arguments further on the subject. When Mother makes up her mind, it can't be swayed by outside forces. "You can call us Abelgard and Shiori. Please make yourself home, [First]."

Father's eyes glance at the door and Mikasa takes a few steps back, but it's too late. "We know you're there already, Mikasa," he says with a knowing smile on his face. Mikasa groans quietly at the failure of her hiding place as she slowly opens the door, the creaking sounding ten times louder than normal. "There you are. Say 'hello' to [First], he'll be staying with us for a little while to make up for the pie, okay?"

Mikasa hides behind her mother to avoid looking their guest in the eye. "Hi," she grumbles quietly, hoping that would suffice.

"[First] will stay in your room while he's here, okay, and you can sleep with Mom and Dad, alright?"

"Mmhmm."

"Um," [First] pipes up after all his silence.

"Yes?" Father turns his attention back to their guest who would now be staying in Mikasa's room with her favorite dolls and the perfect view of the flower patch she had planted that was finally starting to sprout.

"I'm not a boy," [First] coughs as light coincidentally peeked through the curtains to shine on her head from the window. "Ba just shaves it off all the time."

Mikasa looks from behind Mother to stare at the girl curiously in her dirty shirt and pants and shaved head. It isn't long before she is hissing from the light pain of a pinch. "Ow!"

"It's rude to stare, Mikasa," Mother warns but her voice isn't harsh. "Remember? We're supposed to be polite when someone is in our house."

I know that already! Mikasa's eyes stare at the floor embarrassed to be scolded in front of someone so publicly. "Sorry," she murmurs instead.

"We should get you some fresh clothes so you can have those washed," Mother looks back at [First] as if there were no interruptions. "Do you like wearing dresses, dear?"

[First] shrugs. "I've never worn one. Ba said I couldn't."

"We can set out some clothes for you to pick between after you have a bath. Dear, you should get some water and heat it up over the fire for her in the mean time." Mother's attitude had shifted completely and Mikasa feels her embarrassment fade away as she watches in awe of how her mother seems to command the room. Father gave her a playful salute before leaving to do exactly as she asked. Mikasa can only hope that one day she would be just like her. Someone everyone could respect. "Mikasa, you should show [First] to your room and maybe you can even give her a tour afterwards. Do you think you can do that?"

Mikasa nods, not wanting to disappoint her. "I can do it!" She beams when Mother gives her a proud smile. "You're my favorite little helper, Mikasa!" Mother tells her often, it makes Mikasa warm to be.

"[First], where are your belongings?" Mother asks without missing a beat.

The girl points out of the window. "I left 'em under a bush."

"Alright, then you should get those before anything else," with a hint of finality, Mother claps her hands together to signal she is done for now. "Go on now," she places a hand on Mohammed's back and gives her a few pats to encourage the girl to stand. "It shouldn't take but twenty or so minutes for your bath to be ready and the warm water should help with any soreness. Then you can relax for the day before you can help with chores tomorrow."

She stands but the disbelief on [First]'s face is clear to see. She waits a moment, possibly pondering if she should say what's on her mind before ultimately deciding to gather her things without a word. I wonder if we can be friends, Mikasa stares at her back. It's not easy thinking one can be become friends with a pie thief, but if they will be living together Mikasa is sure she'll have to try her best to be polite at most. She will be just as long as no more pies would be lost to acts of thievery.

When the girl is finally out of an earshot, Mikasa asks, "Why would her dad cut her hair off, Mom?"

Mother only sighs, placing a warm hand atop her head gently. "I don't know, dear. And you shouldn't ask unless she tells you she might be very sensitive about it. Her father might not be a good person, letting her on her own like this. So we need to be kind until we're able to get home safely, alright? Can you do that for us?"

Mikasa doesn't understand completely, but she nods anyway. "I can."

Mother smiles brightly, "that's my girl."

You fidget uncomfortably in your dress. I thought dresses were going to be comfortable. They at least looked comfortable from how you saw other girls running in them in Eppelbog the few times you visited. Perhaps comfortability is subjective, though. At least, that is how you feel as your legs feel bare without the sensation of fabric hugging them on all sides closely. Maybe Ba knew they were uncomfortable and that's why they were forbidden. It's a pretty dress you can acknowledge. It is one of the daughter of the house's dresses. It reminds you of the sun with its warm yellow coloring, but it's nothing like how you had imagined wearing dresses. You spin around in the full body mirror, watching as the skirt flutters in the reflection.

Dresses aren't for me, I don't think. But your clothes wouldn't be ready to wear for another few hours after they finish drying.

"Um..." You almost jumps when she finally notices another face looking back at her in the mirror's reflection. "Mom asked me to give you a tour around our home right now."

Mikasa, Mr. Ackerman had said her name was. "Oh, um, hi," you turn around to face the girl properly. You hadn't expected your attempt at theft to turn into this, but it's a lot better than you getting in trouble and going to jail over it. It isn't quite Leipmold, but it still falls in the line of your original plans. You get to interact with different kinds of humans and you make money. Ba wouldn't be mad at that, at least not by much. Then his strict rules would fall by the way side and you would be free to live her life as she desired. You could make friends.

It's just not exactly promising that your first prospective friend is one you tried to steal a pie from. I'll make it work. "You're Mikasa, right?"

The black-haired girl nods, "and you're [First]."

An awkward silence passes between the two of them before you speak up again. Even if the start was the rough, you aren't letting a new friendship fall through your fingers. "Thank you for letting me wear your dress, Ba never let me wear them before. It's very pretty." Uncomfortable but pretty nonetheless.

Mikasa cracks a small smile at that.

"I'm ready for your tour now," you gesture to the door.

Mikasa leads the way with her flats tapping nicely against the wooden floors, your own footsteps in your boots sounding heavier. But you still your their way outside while there is still plenty of sun gracing the cottage. You sighs in relief. The air smells sweeter now that you don't stink among shrubs anymore. The Ackerman home is a nice home even if there isn't much on the land beyond a garden, a shed and a chicken coop. "This is Eunice, Bonnie, Claudette, and Dana, our hens." Mikasa's voice is light with a small smile gracing her face as she points at the birds. "We don't eat them because they lay eggs for us."

"I like Claudette the most," you point at the black hen's speckled-with-white feathers.

Mikasa shakes her head almost immediately. "Eunice is the prettiest," she gestures at the burgundy hen with gusto.

"Claudette."

"Eunice."

"Claudette."

It is a battle with no end before Mikasa's tour takes them away from the coop and to a garden area. "Eunice," you think you had heard under the girl's breath but your belly grumbles when she spots the blackberry bushes.

You coughs do cover the noise, "did Mrs. Ackerman plant everything?"

Mikasa shakes her head and kneels beside a small patch of dirt with buds separating from the main garden. "These are the flowers I planted," the girl says proudly, the sun beaming down on her. You kneel beside her as best you can without getting dirt on your borrowed outfit. "Mom let me do it all by myself and she said they'll finally be flowers in a couple of months!" You know she won't be there long enough for that but you smile anyway.

"Can you eat them?"

Mikasa looks aghast at the very thought, "of course not!"

"You can eat some flowers though," you points out. Like the lavender that grows near her home. Ba sometimes had you collect flowers like chamomile for tea he would brew when it was especially cold.

"These flowers are for being pretty," Mikasa looks at her buds again proudly. "Mom said we can make flower crowns with them and press them too and that I'll be able to keep them forever that way." She stands up, dusting what few specks of dirt that managed to get on the bottom of her dress. "The rest here are vegetables and fruits Mom grows." You try not to look too excited when you stop in front of blackberry bush but it seems Mikasa already has similar ideas. The young girl plucked a berry right off the bush, holding it for you to take. "The berries are ripe enough to pick right now." I'm really happy I tried to steal that pie! "You can try it, if you want."

You take the berry all too eagerly, relishing the sweet taste on your tongue. "Can I have another?" You asks but Mikasa is already picking more, munching on a berry of her own as she places two on your palm. Yes, you will enjoy living with the Ackermans very much.

#look she's writing#snk x reader#aot x reader#mikasa ackerman x reader#mikasa x reader#mikasa ackerman#mr and mrs ackerman

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mistress of Waters: Oshun

Throughout history, water has been used as a symbol of wisdom, power, grace, music, and sensitivity.

Across many ancient civilizations, love was placed under the domain of a particular deity, usually, but not in all cases, a goddess.

In the Classical world, for instance, there were Venus and Aphrodite, love goddesses of the Roman and Greek pantheons, respectively.

In West Africa, the Yoruba people believe in a love goddess named Oshun.

They inhabit the southwestern part of modern-day Nigeria and the southern part of Benin.

Although #Oshun is regarded principally as a goddess of love, there are other aspects to this Orisha.

Oshun is the goddess of love, sensuality, and water and the protective deity of the river Oshun. She is also associated with fertility, lushness, greenness, and life.

Alongside this river is a sacred grove, probably the last in Yoruba Culture, dedicated to Oshun.

When she came down to earth, she wore a gold dress and jewelry. This is why her worshippers also wear gold and yellow attires to honor her.

According to the tales, the gods came down, they completely disregarded Oshun while they engaged in creating the earth.

She returned to the heavens, where she spent time admiring herself in the mirror. Oshun often carries a mirror so that she can admire her beauty.

In the absence of Oshun, the other gods faced difficulties. They could not populate and revive the earth.

They went back to heaven to apologize and beg her. When she came back to the earth, she revived it with water.

Although Oshun governs love and sweet waters, she is also a benevolent deity.

She is said to be the protector of the poor and the mother of all orphans. It is Oshun who fulfills their needs in this life.

Oshun is commonly shown as a beautiful, charming, sensual, and coquettish young woman.

During the slave trade, Oshun was brought to the Americas and adopted into the pantheons, branching out of the traditional African belief system.

#oshungoddess#oshun#oshunenergy#vodou#illustration#artists on tumblr#haiti#africa#astrology#voodoo#waters#african spirituality#african beliefs#esoteric#ancestral work#ancestors#magick#conjure#illustrator#ogoun#oya#iya#shango#damballah#dahomey#guinen

124 notes

·

View notes

Photo

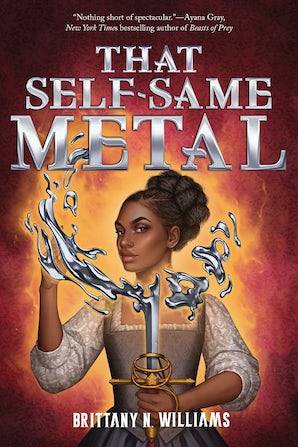

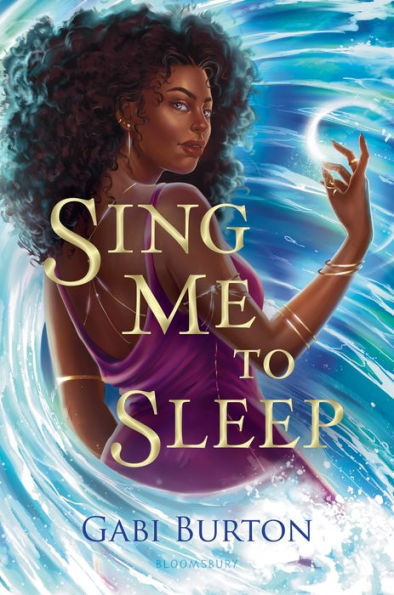

As I was coming up with a shortlist of books to review later this year, I noticed that there were some really great looking fantasy books headed our way in 2023. Here are three that caught my attention, all by Black authors:

Blood Debts by Terry J. Benton-Walker

Tor Teen

Thirty years ago, a young woman was murdered, a family was lynched, and New Orleans saw the greatest magical massacre in its history. In the days that followed, a throne was stolen from a queen.

On the anniversary of these brutal events, Clement and Cristina Trudeau—the sixteen-year-old twin heirs to the powerful, magical, dethroned family—are mourning their father and caring for their sick mother. Until, by chance, they discover their mother isn’t sick—she’s cursed. Cursed by someone on the very magic council their family used to rule. Someone who will come for them next.

Cristina, once a talented and dedicated practitioner of Generational magic, has given up magic for good. An ancient spell is what killed their father and she was the one who cast it. For Clement, magic is his lifeline. A distraction from his anger and pain. Even better than the random guys he hooks up with.

Cristina and Clement used to be each other’s most trusted confidant and friend, now they barely speak. But if they have any hope of discovering who is coming after their family, they’ll have to find a way to trust each other and their family's magic, all while solving the decades-old murder that sparked the still-rising tensions between the city’s magical and non-magical communities. And if they don't succeed, New Orleans may see another massacre. Or worse.

That Self-Same Metal (Forge & Fracture Saga #1) by Brittany N. Williams

Amulet Books

Sixteen-year-old Joan Sands is a gifted craftswoman who creates and upkeeps the stage blades for William Shakespeare’s acting company, The King’s Men. Joan’s skill with her blades comes from a magical ability to control metal—an ability gifted by her Head Orisha, Ogun. Because her whole family is Orisha-blessed, the Sands family have always kept tabs on the Fae presence in London. Usually that doesn’t involve much except noting the faint glow around a Fae’s body as they try to blend in with London society, but lately, there has been an uptick in brutal Fae attacks. After Joan wounds a powerful Fae and saves the son of a cruel Lord, she is drawn into political intrigue in the human and Fae worlds.

Swashbuckling, romantic, and full of the sights and sounds of Shakespeare’s London, this series starter delivers an unforgettable story—and a heroine unlike any other.

Sing Me to Sleep (Sing Me to Sleep #1) by Gabi Burton

Bloomsbury

Saoirse Sorkova survives on lies. As a soldier-in-training at the most prestigious barracks in the kingdom, she lies about being a siren to avoid execution. At night, working as an assassin for a dangerous group of mercenaries, Saoirse lies about her true identity. And to her family, Saoirse tells the biggest lie of all: that she can control her siren powers and doesn't struggle constantly against an impulse to kill.

As the top trainee in her class, Saoirse would be headed for a bright future if it weren't for the need to keep her secrets out of the spotlight. But when a mysterious blackmailer threatens her sister, Saoirse takes a dangerous job that will help her investigate: she becomes personal bodyguard to the crown prince.

Saoirse should hate Prince Hayes. After all, his father is the one who enforces the kingdom's brutal creature segregation laws. But when Hayes turns out to be kind, thoughtful, and charming, Saoirse finds herself increasingly drawn to him-especially when they're forced to work together to stop a deadly killer who's plaguing the city. There's only one problem: Saoirse is that deadly killer.

Featuring an all Black and Brown cast, a forbidden romance, and a compulsively dark plot full of twists, this thrilling YA fantasy is perfect for fans of A Song Below Water and To Kill a Kingdom.

#blood debts#that self-same metal#sing me to sleep#terry j benton-walker#brittany n williams#gabi burton#book lists

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

“You’re well-read, Ezra,” Mirabel remarks, sliding down from her perch.

“I’m well-mythed,” Zachary corrects. “When I was a kid I thought Hecate and Isis and all the orishas were friends of my mom’s, like, actual people. I suppose in a way they were. Still are. Whatever.”

-The Starless Sea, Erin Morgenstern, Book III: The Ballad of Simon and Eleanor, 4th Zachary section

I think this quote is the single most important piece of characterisation for Zachary Ezra Rawlins in the whole of The Starless Sea. Or at least it is for me (though I appreciate that there is a distinction between what you might value as a reader-for-pleasure and a reader-with-hellbent-ulterior-intentions-to-write-this-man-into-a-corner-watch-me-gooo). I kept coming back to this line as I wrote Fateheart (my fan-sequel to The Starless Sea - you can read it here on Ao3), and it has become the lynchpin for a lot of my thoughts about who Zachary is - especially as the story of Fateheart unfolded in front of me and I was trying to keep up with what was happening and grapple with why it felt inevitable.

Here are some of those thoughts, for any of you who are interested in thinking this much about Zachary Ezra Rawlins (and his relationship with Dorian, which is ever central to who he is), about myth, and about The Starless Sea by Erin Morgenstern.

One of the reasons I ended up writing my fan-sequel to The Starless Sea was a desire to continue following the story of what had already begun in Morgenstern's book, which is Zachary's descent into myth - and I don't mean his passage through the wonderlands beneath the world - I mean becoming one himself.

This quote captures what I love most about Zachary and what I find most powerful about him, which is something I came to think of whilst writing as his "belief in the real and the unreal". He is deeply post-modern, and has an acute grasp of myth (gonna define 'myth' in a truncated but convenient way here as a type of story which offers a moral or identity truth, alternative to a history, which gives you facts and assumes the 'truth' is implicit through them). The combination of these two things is very potent, and has allowed Zachary's sense of what is true to develop separately from and at times directly in opposition to what is factual or historically, empirically verifiable. Simply put, when it comes to making sense of his reality, historical truth does not interest him. Stories interest him ("He believes in books, he knows that much" - Book I: Sweet Sorrows, 3rd Zachary section). Not only does a rationalist presentation of value or truth not have any of the significance that it would in a modernist worldview, it is almost irrelevant to Zachary. He does not navigate the world according to its empirical qualities but according to its stories, and he is very adept at reading them, because these are the paradigms by which he got to know the world in the first place.

The blurring of reality into unreality which happens in the quote - he thought that the goddesses were friends of his mother's - "actual people" - tells us possibly more about Zachary's mother than about him. Or perhaps tells us so much about him by telling us about her first: Madame Love Rawlins raised her son in an environment which valued stories, and specifically myths, above all else. Zachary does not gain his sense of identity or context of self whilst growing up from integration into a historical narrative or a sociological connection to his own time or place - even his sense of a wider family context and adult society was defined by a profound connection to a global pantheon of myths. You can imagine how Madame Love Rawlins must have spoken about Hecate and Isis and the orishas - how effortlessly, personally, and often - to create an environment where they seemed this real. And you can conjecture that she herself was not in the business of drawing a distinction between her regular old human friends and the more divine voices of influence over her life. So why should Zachary?

But that blurring of reality with unreality is not nearly as telling as the other blur that happens in the quote above, which is, "I suppose in a way they were. Still are. Whatever."

This is three things happening in quick succession, and I think they are all equally fascinating, and they all delight me equally.

The last and least of them is in the word "whatever": it implies that Zachary is not interested in firmly deciding whether or not he thinks they are 'real' people. "Whatever" is applying to the question of past or present tense, but in its dismissiveness it waives any of the gravity of his placing his blurring of reality in the past. Yes, he's identifying that perception as a younger, past version of himself, but then he brings it forwards, catching himself: "I suppose in a way they were" reasserts the belief; "Still are" updates it, identifies it in himself now; "Whatever" carries it beyond what he feels the need to define.

The second thing that's happening is the "Still are." There is some ambiguity, but not much, in the quote - is Zachary supposing that these mythical figures may actually have been real? That's how I'm primarily reading it because that's the most obvious reading. But one could argue that he's equally supposing that they may well have truly been his mother's friends, and possibly still are - that he's not questioning their actuality so much as the familiarity of their role in one's personal world. They still are friends of his mom's. Or they still are real in some way. Either one is compounded by the "whatever", and "Still are. Whatever" is a telling rhythm of Zachary's thought process here: he is comfortable with indistinction. The factuality is not relevant.

But the most important and the first thing in "I suppose in a way they were. Still are. Whatever." is the supposing itself. That these myths are people who have had an impact on his life relationally, emotionally, interpersonally, and truly. Voices he has known and names he has called and referenced in conversation on the same level as any other. His almost throwaway acknowledgement that this blurring of the line between real and unreal is very much still part of his internal system says a great deal about how deeply foundational this sense of myth and truth is to him: the indistinction is not a problem with the thing, but the thing itself.

And never, in all his academic travels and independent adult life away from his mother (his independence of identity and situation is well established) has Zachary found reason enough to redraw the lines - to reassess this post-modern prioritisation of myth over history - to anchor himself according to what is real, regardless of the value of its truth, as opposed to what is unreal but true. And his wider characterisation as an academic at a good school and a devotee of stories in all forms tells us it is not for lack of self-awareness or intelligence. Assuming he has interrogated his own beliefs before, he clearly has not seen reason to dismantle his worldview. In fact, we possibly see the first thing in his life which really does force him to consolidate his beliefs, and it is not the real challenging the unreal, as must have happened to him and has not left a mark, but the unreal suddenly encroaching upon the real. The moment he assesses this internal balance of the real and the unreal is in the same chapter I quoted above (Book I: Sweet Sorrows, 3rd Zachary section), as he reflects upon seeing his childhood encounter with his door written in Sweet Sorrows and thinks upon what the book is telling him about what lay beyond it:

"He wonders why he believes it because someone wrote it down in a book. Why he believes anything at all and where to draw mental lines, where to stop suspending his disbelief."

Zachary is aware that he primarily operates in a territory where all disbelief is permanently suspended: this is not him asking whether he should start believing that this door did in fact lead to a Harbour - this is him wondering if he ought to believe this much that it does - and what it means for anything real if he carries that belief forwards as he intends to. Questioning whether the space he holds within him for the powerful truth of myth is now starting to truly consume the concrete, factual world in a way which is leading him into new territory. And it is. The mythical does in fact start to consume the real world for him. That is what happens to him in the rest of The Starless Sea. And this is the moment we see that crossover: he chooses to remain faithful to the unreal, and to pursue a story. He asserts what he was raised believing, which is that the unreal is more true and more valuable than the real, and therefore ultimately must be more real. Only someone who is intimately familiar already - from their earliest childhood - with the blurring of these lines - would react the way Zachary has to finding himself in a book - running with it, and allowing it to envelop him completely, as he is ultimately enveloped by the door, the Harbour, and the Starless Sea itself.

And what I love most about this passage is that we see it happen - we see him interrogate himself, we see him follow his internal logic, and we see his belief in the unreal win:

"Does he believe that the boy in the book is him? Well, yes. Does he believe painted doors on walls can open as though they were real and lead to other places entirely? He sighs and sinks below the surface."

To be fair he is in the bath in this scene, but also: "he sinks below the surface": he submits to the authority of myth over fact. And - crucially - to him, myths are real not as accounts of an abject moral value or a history, which is still quite abstract - what's real to him is myths as people.

Writing Fateheart was an exercise in loyalty to characters I fully believed in deeply, and for different reasons. I could write this much again about Madame Love Rawlins (and might/probably will) and Kat (might/probably won't) and don't get me started on Dorian (will/definitely will), but Zachary led the way for me here. I was fascinated - absolutely, devotedly transfixed by the process we get to see the start of in The Starless Sea, which is Zachary becoming part of a myth. He is the close of one story and then the beginning of the next, stepping from the periphery of one myth to the heart of the next.

So that became the paradigm for Fateheart: how do I take these characters, all of whom start as human, and draw from them a new myth? A story which is at once human and deeply personal and realistic in the sense of being true to human experiences of feeling and danger and cost and wonder and love, but is also more than itself - is broad and vast and contains profound, elemental gestures towards values and archetypes and fundamentals of what we are and choose and love as people?

And Zachary made it so easy. Because the myths are already people to him - real, breathing, blooded people. So his passage into that role was intuitive.

I find it wonderful that in the title quote here Zachary is correcting "well-read" to "well-mythed" - the difference is not one I was immediately tuned into, but one which turned out to be vital. He is able to navigate stories so cogently not because he knows them as books, but because he knows them as people. There is a reason he understands Mirabel the way he does - and loves her. He is used to relating to mythical, archetypal powers as close personal friends: he's been doing it since he was a child. Maybe meeting Mirabel forces that mental pathway out into the open - and cements it for him - but it was already there.

It is also the reason he is able to love Dorian the way he does - deeply, intuitively, and uncompromisingly. This relationship was a joy to explore for a number of reasons (most of which are bleedingly obvious hello i am a fanfic writer) but the most captivating dynamic (for me) is their respective positions with stories. Dorian tells them, carries them, gives them - Zachary receives them, loves them, and keeps them.

There's a language that developed organically for this as I was writing Fateheart, and actually grew from Morgenstern's own imagery: the deep night sky within Zachary - which in terms of vernacular I extrapolated from the details of Allegra's painting ("Zachary’s chest is cracked open, his heart exposed, the star-filled sky visible behind it"), developing into a way of referring to that space of pure and certain belief in the unreal - a vast constellation of myths, points of truth which connect across empty space to make sense of the world - which is Zachary's internal landscape.

When Dorian sits in the Gryphon bar and watches Zachary he cannot read him - though it is made clear that he can read just about everyone and everything else, and has been able to do so most of his life. What, then, is Dorian seeing? Most people are reducible to stories, but myths do not reduce to stories - they reduce to truths. Stories, at their best, might extrapolate to myths, which in turn reveal true things, but people are not usually myths - or if they are, they are myths first, masquerading as people (there are plenty of those in The Starless Sea.) And in Fateheart, I try to push this the other way by having three people slowly begin to masquerade as myths. And Dorian sees it first - long before there is language for it - or need for language for it, because, admittedly, there isn't need until you get deeper into the narrative of Fateheart. But Zachary is not a series of facts that build a narrative: he is a constellation of personal relationships with myths. He is a system of beliefs which merrily crosses the boundaries between the real and the unreal in a superb tangle of truths.

Dorian cannot read him because he is not a story. Nor is he, at that point, a myth - but he is a man whose grasp of the world hovers over the edges of what is real, prepared when push comes to shove to fall straight down the rabbit hole. Dorian cannot reduce him because he is already more than himself, hovering in the doorway of the unreal, beginning to follow his age-old belief into territory Dorian has been living in for a long time: the borderlands. Walking the face of the real world but allegiant to the unreal one.

How must Zachary have looked to him? An academic, operating within the structures and annals, the very factual, papery, process-laden architecture of the strictly real - yet relating to it as if it is one myth amongst many. Post-modernity in action: the historical, the rational, the empirical is just one more story. No more or less real than all the others he met at his mother's knee.

And how must Dorian have looked to Zachary? A man who clothes himself entirely in stories - who weaves between the language and the embroidered details of fables and legends and books - moving too quickly to be framed as either fact or fiction. Comfortable presenting the truth in a myriad of ways - with any name he chooses, in any shape he wills.

Dorian presents himself as a story - not just to Zachary, but to the world. Because it is an extraordinary position of power and an acutely slick one: in a world where most people think stories are not real and value them accordingly lowly, being a story allows him to control how he is perceived. From his name to every farthest extrapolation of his position and occupation he presents as fictional. Which is a very guarded way to walk the world. But Zachary draws absolutely no distinction between the people in his life who are stories and the stories in his life who are people. So Zachary is able to simultaneously accept that Dorian is a story and that he is a real person - able to hold the real alongside the unreal, and able to love it entirely as a self-contradictory package deal. Which must have been deeply disarming for a man who has mostly found that his ability to tell a story makes for a good way to present a false identity. Dorian is very good at being a story, but stories at their best extrapolate to myths, and Zachary knows how to love myths as people. He's been doing it all his life.

And this is where I watched them go in Fateheart. Zachary is more equipped to understand Dorian than Dorian is. He readily opens to him the space he holds within himself for stories - the well-populated night sky of the mythical, the unreal, the wondrous, the true. Zachary is a very, very good reader - which I am asserting by my own metrics, but I'll define it as this: if you can hold in perfect conjunction that a story is not true yet contains truth and is therefore more true, then you are a good reader. You can get more out of a truth if it's told in a good story than you can if it's presented as clean fact: a clean, dry bone of a fundamental is very clear and easy to handle, but you can see best how it moves when it is part of the dancing flesh of a living body - even though on one level you cannot see the bone anymore at all.

Zachary sees all the dressing and falls in love with the truth of who Dorian is - not in spite of the stories he hides within but because of them. He offers Dorian a way to make sense of himself - a way to make sense of his entire life, which has seen him caught over that boundary between the real and the unreal - serving a Harbour he never sees, hunting those who cannot be killed. Hiding in plain sight, operating beyond the limits of the real world without ever being free to cross into the unreal. And that grey area is very familiar to Zachary - he is unbothered by it and comfortable there.

And in return Dorian is the consolidation of Zachary's belief in the real and the unreal: he is at once a person and a story of himself. He is blisteringly close to being only the stories he tells and is told, and existing primarily as a way of delivering and performing those stories - and Zachary perceives him as an entire constellation: taking the stories he has become and focusing upon the truth in them. Seeing the bones in him even as they dance. Loving him as myth and human at once without drawing a distinction - and without needing to.

Writing Fateheart was an opportunity (or really a shameless excuse) to explore Zachary and Dorian's relationship with each other. They are just on the cusp of their lives colliding at the end of The Starless Sea, and there is enough substance there, enough tantalisingly unconsummated (ahem) chemistry, that it is a legitimately fun exercise to carry it forwards and see what happens. And I was delighted over and over again in writing them to discover the myriad ways in which they work together - ways they understand each other and overlap and seem stronger for it than they did on their own - all of which is full credit to their original characterisation. I had a distinct impression of following events that had already been set in motion - and rather than developing what an active, steady relationship looks like from scratch, revealing the outworking of what it promised to be from the off.

The blurring of these boundaries between the real and the unreal is literalised in their passage through the caverns of the Starless Sea: the two of them cross into fairytales, into stories and the settings of fables Dorian has told and memorised and had tattooed into his skin. But I do not think that their respective motions are in mirror image - for all Dorian is already living in the unreal, I think it is Zachary who carries the two of them into the territory of myth. In The Starless Sea they each traverse a wilderness of literary and mythical realities in an effort to find each other, but it is Zachary's trajectory that shapes the language surrounding him and his increasingly mythical identity in the book:

"And so the son of the fortune-teller does not find his way to the Starless Sea.

Not yet."

- Book I: Sweet Sorrows, chapter three - To Deceive the Eye

Zachary's process of heading down the path of fully embracing the unreal is his journey to the Starless Sea. The story hits its climax - and the old Harbour finds its breaking - when he finds it - but his actual passage into it is through the death of his physical, actual self.

Which, of course, comes at Dorian's hand. But the action of killing Zachary is two-fold: he frees him from the last traces of whatever he was clinging to of real, rational, folllowing-the-rules-of-a-normal-world life by pushing him entirely out of the world and into the place where the bees dwell - where the old gods are larger than life - where real, rational, following-the-rules-of-a-normal-world business is a vague, dollhouse style, boxy, undetailed approximation - a secondary feature, one worldview amongst a bigger context - and where he eventually drowns in the essence of the story itself, despite his final efforts to escape this. And then the completion of the process is to bring him back to the world - to take his body and replace the heart of what he is with something that is itself a story - a myth.

Dorian and Zachary are falling increasingly in sync with each other throughout The Starless Sea, but it is Zachary who leads the two of them to the shore of the thing itself - the very edge. Dorian is looking for a way to get home, which turns out to be Zachary, and Zachary is looking for a way to the Starless Sea, which turns out to be Dorian.

Dorian giving Zachary the heart - which is the heart of a story - 'of' in the sense of its position at the centre, but also in the sense of 'a heart produced by, having its origins in a story' - is the resolution of Zachary's passage into myth. He has travelled all the way to the Starless Sea - he has submitted to the dismantling of any last vestiges of scepticism in the face of the magic or absurd to such an extent that he has died for it - and then he is brought back.

And for what? To drift on a ship in the belly of the world, out of time, out of the story? Or is the absolution of his identity in that death and resurrection enough that wherever he goes he will bring with him the central, burning core of belief that makes stories like these possible?

At the beginning of The Starless Sea Zachary is in the process of returning to his old favourite books:

He has been reading (or rereading) a great many children’s books as well, because the stories seem more story-like, though he is mildly concerned this might be a symptom of an impending quarter-life crisis.

- Book I: Sweet Sorrows, chapter 4, first Zachary section

The eclipse of the mythical over the real, the reconnection with the powerful, foundational truth that what is fictional is just as real as what is physical, is already hinted at here: his instinct to draw closer to what seems like a purer form of story - worlds where the lines are blurred more perfectly, where the distinctions are already eliminated. This is the first sign of his overall character arc in this book - and it ends with he himself becoming a story.

And I love that he's concerned this might be a symptom of an impending quarter-life crisis. And I love even more that he's only "mildly" concerned. Because that's so Zachary: an intuitive sense that something's coming, and possibly something huge - and his response is to turn back to stories. The "mildly" here has the same feeling as, "I suppose in a way they were. Still are. Whatever." He is easy with a sense of deep upheaval. Because you can't shock someone with the unreal when they've known it all their lives.

He didn't open the door because he wanted to keep on believing that there was something behind it. He has resisted re-wiring his sense of how real all the orishas are not because he wants to keep on believing and knows he won't if he looks too hard, but because he absolutely believes it but is fearful of what this will mean for his grasp on the rest of reality and his place in it. Because really embracing this postmodernity means accepting that everything ultimately reduces to myth. That to walk truly in the deep places of what it means to be alive does not mean banishing a sense of madness but embracing it - following through to the point of total undoing - death of the real self - and further than that, into a new kind of life.

To sail the Starless Sea is to become the story of oneself. The air is haunted by the death and reformation of what is real. Only the bones of the real things ever return - dancing as part of the flesh they have been clothed in. Truth that is clothed in stories: myth.

Zachary Ezra Rawlins has known since he was a child that stories are true. And maybe his hesitancy to embrace this has been because he knows that if he embarks on this hero's journey he will have to leave behind anything that might resemble his own sanity by the world's standards. He knows that to embrace those relationships with the mythical as closely and as truly as he did when he was a child learning to relate to his mother's circle of friends will be to become himself a story. To relinquish his grip on the rational and to give up, ultimately, his heart.

To go mad, and to return more deeply yourself than you could ever have anticipated.

And you know who gets this? Dorian.

“How are you feeling?” Zachary asks.

“Like I’m losing my mind, but in a slow, achingly beautiful sort of way.”

“Yeah, I get that. So better, then.”

- Book IV, Written in the Stars, 3rd Zachary chapter

That's the second most important line for Zachary's characterisation - in my opinion (and let's face it when it comes to Zachary Ezra Rawlins I have an absolutely absurd amount of opinion). That once he chooses to cross the threshold of the world and walk the halls of a myth he's always suspected he had a part in, he knows that by some standards he is losing his mind - the rational part of his 'self' - his life, by the standards of what the world thinks a life is.

But he's only mildly worried about it. He's never really held much with the sense that rabbit holes ought not to be for falling into. That he should be beyond it. That it shouldn't be real.

The point of departure for Fateheart was a Zachary who has finally, with the aid of Dorian, become himself. A Zachary who has left behind the world and the life that went with it. A Zachary who is so at one with the mythical that he himself is a myth. Zachary at the final, gasping, awakening stage of losing his mind - but in a slow, achingly beautiful sort of way.

"So better, then."

A myth. A story told by someone who loves him well enough to bring him back as exactly what he always was: a heart alive and alight with the unreal, carrying it in the vast night sky within him, bright enough to illuminate the world and reveal all the things in it that have always been true:

[an] enormous, spinning truth, turning like a star in the sky, close enough to be a sun, burning with enough light to illuminate the world.

- Fateheart, part two, chapter 16

And Dorian follows him there - is the agent of the final stages of this transformation. Is the hand by which the story is told: one who tells the story, one who carries it.

It felt like the most obvious thing in the world that on the strength of such a pairing one could dream a whole new story - felt, to me, like it was clear that having transcended into myth, the new Harbour could and would form around them - could have at its centre a love story that is at once about real people and about something mythical.

The old myths are completed, and the new myths find their footing at the end of the story. And I wanted to know - was absolutely desperate to see - what the next story would look like, with these two people at the heart of it.

So that's what I wrote.

--BoogleBoot

#Zachary Ezra Rawlins#The Starless Sea#Erin Morgenstern#Fateheart#literature#books#Dorian#character study#I could write for this long again about Madame Love Rawlins alone#and don't get me started on Dorian#actually do#someone I beg you#I have so many thoughts about that man#about both of them

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

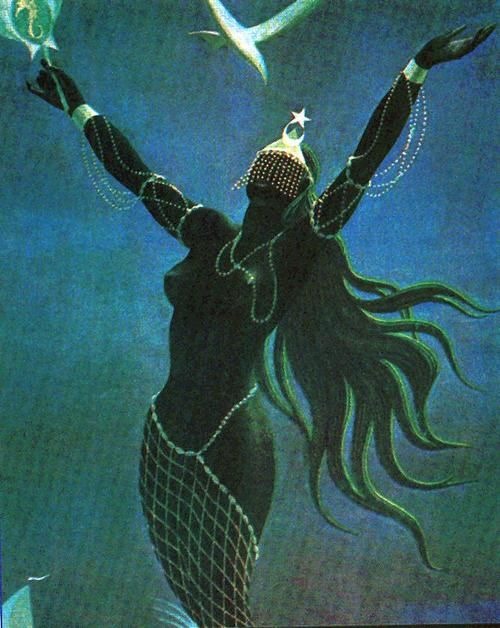

Amazing! Known artists are watermarked, unknown artist are not.

ARTWORK IN HONOR OF: Yemonja, Yemonja, also spelled Yemoja or Yemaja, Yoruban deity celebrated as the giver of life and as the metaphysical mother of all orisha (deities) within the Yoruba spiritual pantheon.

Art: Apollo Inspired. Apollo is mostly known for being the God of The Sun and Light. But he is also the god of poetry, healing, music, plagues, knowledge, order, prophecy, beauty, agriculture, and archery!

Concept Artwork of Ma'at. Maat or Maʽat comprised the ancient Egyptian concepts of truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality, and justice. Ma'at was also the goddess who personified these concepts, and regulated the stars, seasons, and the actions of mortals and the deities

#black artist#blerdsunited#blerds united#blerdcommunity#blerds#blerd community#black art#black nerds#blackartists#art#artists#goddess#gods#black#character ai#ai artwork#ma'at#mafdet#apollo#yemoja

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yemaya Blessing Bath.

In Africa in the Orisha practices of Yoruba, she is known by her Nigerian name Yemonja aka Yemaya is what she's called in the new world like the Americas. She is the Goddess Orisha of the ocean. She is thought by some to be the mother of the world. It's not uncommon to a hoodoo practicer to be a devotee or just want to pray an Orisha or Loa.

Number is 7.

Colors. All types of blue.

Her work helps to bring Peace and Abundance into your home. She's a Orisha of prosperity. She appears as a mermaid to some other times something else. She is syncretized with the image of Mother Mary. Because she is a mother figure.

She is good deity to work with even if your practicing hoodoo. If you became a priest/ess of her's or just a everyday devotee of her's or if you just like her and want to do some workings with her. She is great for helping and protecting children and families.

Starting A Bath

For this bath you'll need the following

Salt

Cascaria or Efun.

A small blue candle or a large glass Yemaya candle.

Blue indigo. ( liquid or dry).

Bowl

You will start by putting the dry ingredients in first (#1 & 2) in your bowl. Next add your water, you can use any water I like to you use rain water. (It's more natural)

While your pour ask her for piece in the home or abundance, protection, health etc. You can say a prayer to her if you like.

Once the dry ingredients has dissolved add your blue indigo just a little, enough to make the water blue because it can stain. If you have her oil or a perfume of hers you can add that also.

You can also buy her wash and add the dry ingredients to it if you want to.

LAST place your candle in the middle of the bowl and light. You are doing this to hornor her and asking her for what you need. You're also blessings and charging the bath to be used.

After you talked to her and the candle is done you can used the wash.

#like and/or reblog!#spiritual#google search#rootwork#follow my blog#yemoja#Orisha#Yemonja bath#Spiritual wash.#Spiritual bath#Yemaya bath#african american hoodoo#traditional rootwork#traditional hoodoo#southern rootwork#southern hoodoo#Orisha bath#ask me anything#message me

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

ORISHAS IN THE IFA TRADITION

Orishas, also spelled Orisa, are natural forces or supernatural entities of the universe. These spirits are also referred to as deities or gods of the elements in the Ifa tradition of West Africa. They serve as conduits or intermediaries between humans and the Supreme Being (Olodumare) to benefit and help humans enjoy life.