#peninsular war

Text

The Scouts (A patrol of the 10th Light Dragoons, Peninsular War)

by William Barnes Wollen

#william barnes wollen#art#peninsular war#napoleonic wars#scouts#dragoons#hussars#great britain#britain#england#british#english#cavalry#history#spain#europe#european#dragoon#hussar#napoleonic#royal hussars#royal#iberian peninsula

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

Francisco Goya El tres de mayo de 1808 en Madrid (The Third of May 1808). 1814. Oil on canvas: 268 × 347 cm (106 × 137 in).

#francisco goya#war#napoleon#1800s#horror#madrid#spain#19th century#history#dark#art#politics#art history#peace sign#painting#macabre#oil painting#chaos#culture#peninsular war#disasters of war#🎨 📚

291 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(Photo: Carmen Escobar Carrio)

Juana Galán - Heroic guerrillera

When the French invaded Spain during the Peninsular War, some women were determined to resist. Among them was Juana Galán (1787-1812), the daughter of a prosperous tavern keeper.

On June 6, 1808, a column of 1,000 enemy troops attacked the town of Valdepeñas. Juana rallied the townswomen under her command. They manned the windows and threw boiling water and oil at the enemy.

Juana went to the street armed with a club. She reportedly pulled several French soldiers from their horses and dispatched them with a blow to the head. The townspeople’s fierce resistance forced the French to retreat and never return.

Juana didn’t live to see the end of the war. She died in 1812 while giving birth to her daughter. Her legacy lives on and she was made a local heroine and a symbol of resistance. She now has her own monument in Valdepeñas.

Like Juana, other women fought in desperate situations or during riots, sometimes with improvised weapons. In 1809, an unnamed woman armed with a sword rallied the inhabitants of Penafiel (northern Portugal) and led them in battle against the raiders. In 1811, María Marcos, a tavern keeper from La Palma del Condado, played a key role in repelling a small group of French soldiers.

There were also cases of women involved in guerrilla warfare. The Catalan Somatén, a paramilitary defense organization, had female members such as María Escoplé, Magdalena Bofill, Margarita Tona, María Catalina and Catalina Martín. Francisca de la Puerta reportedly fought in Extremadura and commissioned the Junta of her province for permission to form her own guerrilla band.

Wanting to avenge her father and brother, Martina de Ibaibarriaga Elorriagafora disguised herself as a man and led a guerrilla band until she gained a commission in the Spanish army. An unnamed woman was given the command of a troop by the Junta of Molina de Aragón in 1809. A British officer also mentioned women serving with bands of irregulars as active combatants.

For more heroines of the Peninsular War, see Agustina de Aragón.

Feel free to check out my Ko-Fi if you want to support me!

Further reading

Esdaile Charles J., Women in the Peninsular War

Sheldon Natasha, “Juana Galan: A Spanish Heroine of the Peninsula War”

#Juana Galán#history#women in history#spain#spanish history#peninsular war#napoleonic wars#19th century#women's history#warrior women#war#women warriors#historyblr#badass women#historicwomendaily#historical ladies#warriors

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

😥 I was working long hours and took even longer to get to work (due to train strike), so I missed Marshal Ney’s birthday. I’m so sorry! I had planned to translate something special, and I hope it’s still a bit of a present even if it’s a day late.

In summer of 1809, while Soult was still licking his wounds after the disaster in Oporto, anxiously waiting for Napoleon’s judgement and trying to defend himself against all the rumours that accused him of high treason, all the while doing his best to bring Joseph and Jourdan to some action against Wellington - guess who at the same time came to Galicia to pay Michel Ney a visit? Right, Ney’s most devoted Dutch fan girl, Ida Saint-Elme! And it’s a particularly romantic part of her recollections, which were published as "Mémoires d’une Contemporaine":

Ney, who was hardly resting either, had just subdued Galicia.

Okay, Soult already wants to protest against this claim, but let’s ignore him. Please, Ida, go on:

I joined his corps at Banos, forty-eight hours before he came face to face with the English army, which the Marshal completely defeated.

Already the spectacle of war, meeting the French battalions, the scent of glory, sweeter to breathe in this country than that of the orange trees that embalm it; this active life, animated entirely by emotion and spectacle, revived my imagination weary of the empty pleasures of the courts and of voluptuous Italy. I felt I was in my element: I was close to Ney, close to the heart that alone could make mine beat. I was happy just to know that he was so close to me and to tell him that we were barely a league apart. Here is the note I received in reply to mine:

"Since it's your taste to have an arm or a leg less, hop on a horse and come here."

As I read this short, military invitation, I jumped in the saddle and rode off.

I had hardly gone a quarter of a league when I met him, and I read in his beaming face all that his note had not told me, the joy of seeing me again, which was the reward for my journey and happiness itself. I have forgotten the names of the places we passed through, but it seems to me that I have never seen a more enchanting place, a more beautiful sky, a sweeter dawn. There was something wild and proud about this rich and picturesque nature.

The road was lined with rocks like a crown. "Here is a magnificent shelter of ravines," Ney said to me, "the tree-lined slopes of which ensure their coolness; let us stop here; you must be in need of rest; we both need to open up and talk;" and here we were, with our horses' bridles slung over our arms, pushing aside the fragrant undergrowth with a vigorous hand, and looking for a retreat that could hear our confidences: it was easy to find in the ravines of Galicia; and, a few hundred paces from the road, we could believe ourselves to be entirely alone in the world. Our horses were quickly tied up, and the secluded spot a little farther on completed the safety of this meeting, so sudden and so little expected. We had been sitting for a few minutes when Ney struck the trunk of an old cedar with his foot, and said to me: "Here, Ida, here is a support for our feet, which will at least save us from a fall;" and, confident in this support so well met, we no longer feared to tread the embalmed moss which served us as a wild divan. I looked at him like one of those figures from a long dream, which the day suddenly shows and illuminates, and which we recognise with all the anxiety and all the troubles of the dream. It's him, though; it's definitely him, I said to myself; I can tell by the glory shining on his forehead, by the pressure of his powerful hand, which is as recognisable as his glory.

Thinking more of the hero than of my love, of the captain needed for his army than of the man needed for my heart, I shuddered fearfully at the thought of this isolation in a country so full of dangers, where a warrior's halt might unexpectedly be surprised by the dagger or bullet of partisans; in a country where hatred of the French name reverberates and watches from mountain to mountain. I felt guilty exposing to these perils, beneath such a great man, a life so dear and so beautiful, that informed assassins could cut it short. It was only a quick thought, but a vivid and gripping one, which, disturbing my thoughts, made me cling tightly to Ney, and as I let out this stifled whisper: "Ney, my friend, let's not stay here; let's go away." - "No, no," he replied, holding me back; "where else would we be, without witnesses to a happiness that I have rediscovered, and which needs solitude and mysterious effusion?" I looked at him with surprise at these words, but with delight, for I was as happy as I was astonished to have remained so dear to him. Never had Ney's face seemed more expressive, never had his looks been more eloquent, never had his words been more intoxicating.

If this was a modern-day AU, this would be the perfect moment for Ney’s phone to ring and for one infuriated Soult to ask why the F he was not receiving any news from Ney’s troops in Galicia. As it was, Ida’s little tête-à-tête with her one-and-only Ney could continue.

At the sight of the security imprinted on the warrior's features, I regained a similar security; there are those moments when everything you feel gives way to everything you inspire. Oh, what inexpressible delights this happiness given by a great man was! Our hearts, separated by such a long time and such long distances, seemed never to have parted, and tasted the pleasure of a similar conviction and an equal sharing of emotions. A new fear came to suspend the enchantment and give it, as it were, all the price of a victory. The reverse side of the ravine which had received us sloped down very rapidly; the trunk of the tree which supported the effort of our feet, a solid yet powerless support, suddenly gave way and broke at the very moment when, immersed as we both were in the rapture of an intimate conversation […]

Listen, it was a conversation, okay? They were only chatting! Intimately chatting!

[…], we had forgotten even the possibility of such a peril, from which Ney's presence of mind and prodigious strength alone saved us: With one hand he seized the branches of the bush that had sheltered us; with the other he pressed and held me violently against him; and, thanks to this struggle, we were able to regain our breath, escape the precipice, and manage to get back to our horses.

I really do not want to know how his aides would have tried to explain the fact that their marshal had fallen into the abyss and to his death while having an intimate conversation. Or why his pants were still up on the cliff...

But if any of the artists out there are looking for inspiration...

Speaking of Ney’s aides, one of them, Levavasseur, in his memoirs has this to say about Ida’s apperance in Spain:

It was at Banos that I saw a French woman arrive on horseback and ask for Marshal Ney. It was the woman who has since called herself la Contemporaine. This woman soon disappeared; what she says about the Marshal in her memoirs is pure invention.

Levavasseur: Don’t you believe what that woman wrote about Ney, she’s a total liar! Besides, she was only with us for a very short time…

But the funniest thing is his casual report on why Ida probably had to leave again so quickly: Ney was already occupied otherwise.

During this trip, the marshal took a tender interest in the duchess; one of my comrades had declared himself the knight of the eldest daughter, and I myself protected the youngest […]

I can’t help but think that the interest the general staff of this army corps was showing to all things female was overly excessive even by French standards… - Wait, what’s that? Oh, another missed phone call for Marshal Ney. Marshal Soult wants to discuss priorities in war times...

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

clearly Masséna is the retweet

#napoleonic era#napoleonic#napoleons marshals#jean de dieu soult#arthur wellesley#peninsular war#napoleonic shitpost

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

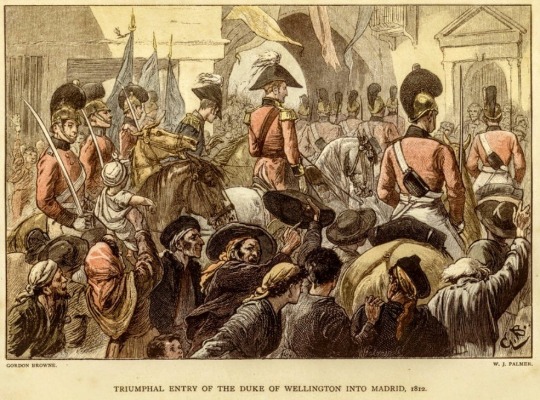

Today, August 12th, in 1812, British, Portuguese and Spanish forces under the Duke of Wellington liberate Madrid, if only temporarily.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peninsular war art? Peninsular war art!!!

Okay, I’m at the Museum of Fine Arts in Valencia and there’s an exhibition of paintings by Joaquin Sorolla Bastida, a Valencian painter from the second half of the 19th century. And wouldn’t you know it, he has 2 paintings about peninsular war!

Here’s his version of Dos de Mayo:

And below we have a depiction of the battle of Valencia. The painting is called “The Baker’s Cry: I, Vicent Doménech, poor baker though I be, hereby declare war on Napoleon. Long live Ferdinand VII and death to traitors!” (Vicent is a Valencian and Catalan name btw, the two languages are very similar.)

While the paintings were created long after the fact, I thought I’d share them here! Oh btw, that Ferdinand endorsement aged like fresh milk in the sun. The guy was conservative as Hell.

As a side note, remember how I mentioned Asensio Julià? Goya’s assistant and apprentice who got a cameo in Hasegawa’s manga? Well, I saw 2 of his paintings in a different exhibition so here you go:

Oh, just so you know, Julià seems to be the most famous out of all of Goya’s apprentices. And Julià was Valencian, just like Sorolla.

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Francisco Goya - Giant Seated in a Landscape, etching with aquatint, ca. 1818.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soldado inmortal

«Había mucha literatura en torno a él y a sus semejantes. Se decían fieles a sus señores, fieros guerreros que apenas se inmutaban al ser atravesados por el acero y, cuando sus enemigos lograban hacerlos sucumbir, volvían de entre los muertos para atormentarlos.

Sin embargo, España a veces dudaba de las lealtades de sus semejantes, además de las suyas.»

¿Yo, procrastinar dibujando sobre la época sobre la que debería estar escribiendo? Por supuesto.

Y me había olvidado de la maldita sangre.

#aph spain#hws spain#soldado inmortal#peninsular war#headcanon#historical hetalia#la buena noticia es que me he dado cuenta de que sé dibujar manos 🤣#a decir verdad#iba a hacer un dibujo con él vestidito de chulapo#pero tenía ganas de representar esta escena#(son los tres de siempre)

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon at the surrender of Madrid in 1808

The disaster at Bailén was followed on August 30, 1808, by the surrender in Sintra of French general Junot to the English. Napoléon, commanding 200,000 men, intervened on the Iberian peninsula, retaking Madrid in November 1808. Depicted here is the surrender of the capital, which he would hand over to his brother Joseph. A humane man of abundant good will, Joseph was dubbed by one of his biographers “the philosopher king” and by another “the king despite himself.” He tried to be a modern monarch and to reform Spain with Enlightenment ideals, claiming to work for the good of “his” people. Cut off from the populace, confronted by merciless guerrilla tactics, and facing down an English expeditionary corps, Joseph would never achieve his goals.

Source: Thierry Lentz

#madrid#Spain#Joseph#joseph bonaparte#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic era#napoleonic#peninsular war#españa#first french empire#french empire#19th century#France#history#art#painting#art history

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Guerrilla warfare during the Peninsular War", by Roque Gameiro, in Quadros da História de Portugal ("Pictures of the History of Portugal", 1917).

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conquered but not Subdued by Richard Caton Woodville Jr.

#richard caton woodville jr#napoleonic wars#art#prisoner#napoleonic#highlander#highlanders#cavalry#peninsular war#british#scottish#french#spain#france#britain#great britain#scotland#england#europe#european#history#chasseurs#chasseur#hussars#hussar

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Found this plate at the antique market today.

Battle of Somosierra, Peninsular War

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Agustina de Aragón, Casta Álvarez and other heroines of the siege of Zaragoza

In 1808, the Spanish city of Zaragoza was besieged by the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte. The Peninsular war was raging as the Spanish people resisted the French occupation.

Women distinguished themselves in defense of their homes. One of them was Agustina Raimunda María Zaragoza Doménech (1786-1857), also known as Agustina de Aragón.

Defender

In 1803, she married Juan Roca Vilaseca, a corporal in the Spanish Artillery. Since her husband had been stationed in Zaragoza in 1808, Agustina was present when the French troops besieged the city.

Many of the Spanish defenders of the strategic Portillo Gate had been wounded or killed following the French assaults. The enemy was beginning to storm the city. Agustina, who had been carrying food and water to the soldiers, stepped into the breach, retrieved a still-burning wick from the hand of a fallen gunner, and fired the cannon at the advancing French soldiers. Her courage rallied the defenders who repelled the assailants, thus saving the gate.

The Spanish Commander in Zaragoza, José de Palafox, heard of her bravery and rewarded her. Her exploit also won her international fame. Lord Byron wrote, for instance, a poem in her honor.

Zaragoza’s other heroines

She wasn’t the only woman to take arms. Another was Casta Álvarez (1786-1846). Armed with a bayonet, she defended the Sancho Gate and was later awarded a pension by King Ferdinand VII.

Manuela Sancho (1783-1863) fought to defend the San José convent, riffle in hand. María de la Consolación Azlor, countess of Bureta, (1773-1814) organized a battery to repel a French assault on her home. The names of Benita Portales, Juliana Larena, and María Lostal are also remembered. Women also nursed the wounded and brought food and drink to the soldiers. María Agustín (1784-1831) was, for instance, wounded when bringing ammunition to the defenders.

This first siege ended on August 14, 1808, but the French returned to besiege the city on December 19, 1808. Agustina wanted to fight but had contracted typhus and could only watch from her sickbed as the city was taken. Captured by the French, she and her son were forced to march to the frontier among a column of prisoners. She would probably have died if an officer had not placed her on the back of a mule. Agustina made it to Puenta de la Reina where she escaped. Her son died shortly afterward.

Ensign

Agustina reached the nearest headquarters of the Spanish army. She was made an ensign and served with her unit in Seville. She later fought in the defense of Tortosa and the battle of Vitoria, though her participation in the latter is subject to doubt.

After the end of the war in 1814, Agustina followed her husband to various military posts. After he died in 1823, she remarried to a doctor. She died in Ceuta on 29 May 1857.

Further reading

Esdaile Charles J., Women in the peninsular war

Fernandez Gilbert G., “Agustina de Aragón”, in: Bernard Cook (ed.), Women and war, an historical encyclopedia from antiquity to the present vol.1

Lawrence Tone John, “Aragón, Augustina”, in: Higham Robin, Pennington Reina (ed.), Amazons to fighter pilots, biographical dictionary of military women, vol.1

Navascués Alcay Santiago, “Casta Álvarez Barceló”

Solduga Francisco Javier, “La Artillera del Portillo”

#Agustina de Aragón#Casta Álvarez#Manuela Sancho#María de la Consolación Azlor#history#women in history#spain#spanish history#warrior women#napoleonic wars#peninsular war#siege of zaragoza#zaragoza#women warriors#warriors

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brun de Villeret about Marshal Victor

Claude-Victor Perrin aka Marshal Victor is one of the marshals I know the least about. So I was quite happy to find Soult’s aide de camp Brun de Villeret wrote a bit about him in his Cahiers. As this journal was never intended for publication, it’s likely to contain Brun’s honest (if possibly exaggerated) opinion.

Victor was, together with Mortier, one of the marshals who found themselves under the superior command of one marshal Soult during their sojourn in Spain (and didn’t like it one bit). Victor specifically was tasked with the siege of Cadix. When Napoleon sent Masséna into Portugal in the third and last attempt to occupy the country, he demanded Soult come to his support. Soult decided to besiege the fort of Badajoz together with Mortier and for that purpose had to take a larger number of troops from Andalusia into Estremadura, stretching himself dangerously thin. The Spanish troops in Cadix used that opportunity to attack Victor’s siege forces and even had some small successes before being driven back into Cadix. As Brun puts it:

[...] Some of our redoubts had been taken and demolished. The damage was easily repaired, however, and the Duke of Bellune could only congratulate himself on his victory and the way he had conducted his business.

Unfortunately, the gloomy mood which dominated him and still dominates him in all the circumstances of life, led him to believe that the Duke of Dalmatia had wanted to sacrifice him, by weakening the forces he had in Andalusia and taking the Duke of Treviso to Estremadura. He wrote him bitter and reproachful letters. As I was on fairly intimate terms with him, given that my brother was one of his aides-de-camp and had his confidence, the Duke of Dalmatia thought it appropriate to send me to him as a mediator, with the mission of trying to soothe his bad mood.

I see. The Brun brothers. Unofficial psychotherapists of the Armée de Midi.

I found him furious. He had retired to bed and received me while in bed. For two hours, his ravings were so violent that it was impossible for me to reach the end of a sentence. Finally, exhausted from shouting, he allowed me to speak.

Brun: Can I say something now?

Victor [sheepish]: Yes. I am hoarse and my throat hurts.

I managed to make him understand that with his talents, his reputation and three divisions as fine as his own, he should not be surprised that the Duke of Dalmatia had counted on him to defend his lines and cover the south of Andalusia.

"You have," I finally said, "responded perfectly to this hope and added a fine jewel to your military crown. For our part, we have obtained great results [...] In short, since success has crowned your defence as well as our undertaking, you would be doing yourself a disservice in the eyes of the Emperor if you were to cast a negative light on what has been achieved."

While I was speaking, his face had become serious, and he had resumed that air of benevolence he had always treated me with, when I did not have to address him on his relations with the Duke of Dalmatia. He even showed me the most delicate attentions and sent me away very satisfied with the result of my mission, and bearing answers written in a perfectly moderate style. I knew how to deal with him, and the Duke of Dalmatia knew it too: let him exhaust his ire and his verve. Afterwards, he would listen to reason. Also, during my stay in Spain, I had the opportunity to carry out several missions of the same kind.

One of them apparently included Victor shouting to Brun for another hour about how Soult never sent him enough food and how he was about to starve with his troops, before Brun finally could present him all certificates of receipt for Victor’s corps, proofing that the food Victor claimed was missing had very well arrived, and announce that Soult, nevertheless, had sent off some more boats with food for Victor’s corps. As Brun remarks at this occasion, Victor was "a better warrior than a good administrator".

But my favourite part about the scene Brun describes is that Victor apparently, all the time while he was raging to Brun about Soult’s injustice, was lying in bed. So he was like, yelling at the ceiling, his head in the pillows? Did he also wear a night gown and a sleeping cap?

#napoleon's marshals#claude victor perrin#jean de dieu soult#napoleonic era#peninsular war#siege of cadix

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sharpe nearly giving himself whiplash whenever he hears Teresa’s name 💖

#sharpe#sharpe's eagle#sharpes eagle#richard sharpe#major hogan#napoleonic wars#peninsular war#(i love this scene so much he's SO excited to hear her name)#(like a golden retriever)#(hogan: you wanna see....teresa?)#(sharpe perking his head up and wagging his tail: TERESA?? TERESA?? :DDDD)#sean bean#brian cox

138 notes

·

View notes