Photo

"En effet, la musique a seule le pouvoir d’évoquer à son gré les sites invraisemblables, le monde indubitable et chimérique qui travaille secrètement à la poésie mystérieuse des nuits, à ces mille bruits anonymes que font les feuilles caressées par les rayons de la lune."

(In effect, music alone has the power to evoke of its own accord the ineffable places, the unquestionable and chimerical world that works secretly on the mysterious poetry of the night, on those thousand anonymous sounds that are made by the leaves as they are caressed by the rays of the moon.)

—Claude Debussy, Monsieur Croche, antidilettante

Librairies Dorbon-aîné ; Nouvelle Revue française (Les Bibliophiles Fantaisistes), 1921

I came across this quote while rereading Paul Griffiths' excellent book on twentieth century music, Modern Music: A Concise History from Debussy to Boulez (1978), which sent me to a collection of essays and opinions (penned by Debussy under the pen name of Monsieur Croche).

It was Griffith's view of Debussy as a "stealthy revolutionary" that influenced my own views of his work at a time when I was attempting to understand the overall scope of twentieth century music in its closing decade. Jeux (poème dansé, 1912) was key to this understanding, as it was one of Debussy's final works, performed only weeks before the epoch-marking performance of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring.

>Yet in many ways, it is a work of equal power, if delivered in a more genteel package. It presents its themes in brief, feverish snippets that emerge and dissipate, untethered to key or familiar melody. The piece does not "develop" in the familiar ways of nineteenth century orchestral music, nor does it seem to held by any previous tradition. Although Debussy makes use of recognizable instruments and arrangements, the piece seems to exist entirely on its own terms.

As Griffith writes, "Debussy had opened the paths of modern music—the abandonment of traditional tonality, the development of new rhythmic complexity, the recognition of color as an essential, the creation of a quite new form for each work, the exploration of deeper mental processes—but he had done so by stealth." (p. 13)

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

When I first heard the trio called The Young Gods, it was such a momentous sonic experience that even decades later, it doesn’t feel right to explain them as just some cool Swiss band I liked when I was a kid. Hearing them then—as now—feels more like getting swallowed into an avalanche or watching a meteorite careen into the side of the Moon.

The Young Gods were unlike any other band of their time. While they have often been classified as "industrial," they were far more radical than that. The Young Gods were among the first bands to really understand that sampling could be used for far more than just winking references to older music: it could also be used to melt sound down into barely recognizable aural material which could then be forged into something entirely new.

Of course, the band's reference points weren't entirely untraceable. They took most of their energy from thrash metal and punk, but they also reflected a distinctly European, electronic, and experimental sensibility drawn from the avant-garde tendencies of early 20th century songwriters and bad-boy composers (such as Kurt Weill, Igor Stravinski, Edgard Varèse, and George Antheil), and mid-century musique concrète. But the end result was a uniquely primitive and post-futuristic music that has scarcely been attempted since—even by the band itself, which generally took a more mainstream direction after 1991.

Here it is in its rawest, finest glory: “Nous de la lune” (“We of the Moon”), off of their debut, self-titled album from the spring of 1987. It isn’t their first song (since there were two scorching singles released before this album), but it qualifies as one of the most auspicious and unforgettable “first songs” ever put to record.

The track is built from the exquisitely processed slabs of sound created by Cezare Pizzi (layering crowd noise, guitars, bells, and the sound of a collapsing glacier, seemingly) driven by the crisp, march-like electronic drumming of Frank Bagnoud. But the real centerpiece is the guttural, pained voice of Franz Treichler—also the only consistent member of the band ever since—howling in Swiss French.

Perhaps more menacingly than on any other track the band ever put out, Treichler’s vocals pound out words like boulders, with the anguish and petulance of an impatient, immature deity (“Be our mother! / Be our flesh!”; “Send us the storm!”). Much like the band that inspired their name (Swans), the Young Gods here turn catastrophe into music; like a thrash cabaret on the edge of a volcano. The album's artwork—seemingly etched onto the surface of the Moon itself—is therefore a perfect visual analogue to the band's unique sound.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anselm Kiefer, Breaking of the Vessels (1990). Photo by Jan Looper Smith.

Earlier today, a friend asked for some sources of artistic inspiration, and my initial impulse was to share with her a work by Anselm Kiefer. I decided that most of his work was too "heavy" for what she had in mind, but it got me to look at his pieces with a different eye. Yes, they are monumental, weighted with meaning and the material itself (as they are often made out of lead, for example), and arguably bleak by disposition.

But there is obviously more to it than the initial impression. Kiefer's work lends itself to many viewings, and many meanings. I began to understand a work like Breaking of the Vessels as being about far more than just the horrors of Kristallnacht, which it so clearly seems to point to.

As the Saint Louis Art Museum's description of the piece makes clear, Breaking of the Vessels also refers to the Kabbalah, "a collection of mystical writings from the Jewish religion, when the world was created, [when] the attributes of God—his mercy, wisdom, and power—were divided among ten vessels that were not strong enough to hold them, and they shattered into pieces."

Beyond these direct historical and spiritual referents, the value of his work (as this particular piece demonstrates so well) for me is in how it seems to inhabit the world in this weighted way, but also suggests something vague, resplendent, life-affirming, and supernatural. Even as it appears to be viciously, viscerally part of the world (like a shelf of library newspapers after a bombing raid), its haunting beauty is also somehow sublime, like a cathedral or a neglected tomb. Its beauty lies in its very monstrousness.

—Ed Luna

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A handful of selected favorites from Paula Rae Gibson, as featured on LensCulture.

• https://www.lensculture.com/paula-rae-gibson

"This selfie culture unnerves me. Not with teens, that's a whole different thing, but everytime a friend posts a selfie of herself, I think, oh dear, she's at crisis point. She needs to keep seeing her image, know she exists, she feels her life is nothing...that she is fading away.

When my husband was diagnosed with death [c. 2001], our daughter was 20 weeks old. I was the last person on the planet equipped to be a single parent, let alone exist without him, and I started to take photos of myself obsessively. It was an excuse to get dressed, an excuse not to get dressed, it was proof I hadn't disappeared.... been buried with him."

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marc Giai-Miniet

Boîte dite au grand tamis (200?)

Zone de concentration (200?)

(Photos by Michel Dubois)

• Excerpted from M. Kelly's descriptions for Gallery One (Nashville):

The framework and frailties of the human body is often a metaphor built through architecture. In his series of boxes, a tangent and complement to his long career of investigations as a painter, Marc Giai-Miniet explores the idea of architecture as human experience, and as human experience as architecture.

Giai-Miniet balances the handcraft of tiny diorama with poignant explorations through memory, association, and dreamscape. His tiny homes, though dealing with images of mundane possessions, industrial equipment, and furniture, contain an atmosphere at times absurd, surreal, or even sinister.

Many of Giai-Miniet’s tableaus deal with libraries. Rooms crowd with floor-to-ceiling books, spanning floors and floors of shelves. In the lightest sense, these form metaphors for the clarity and redundancy of memory, the archeology of personal and collected narratives, and a geological collection of sentiment on object; in the darkest sense, descending through increasingly poorly-lit levels [...], they verge on the edge of overwhelming the space, a bibliophile’s hoarding bordering on obsession and a deeply rooted fear of forgetfulness and loss.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Detail of diagram and strip of film from Peter Kubelka's Arnulf Rainer (1958–60), "35mm, b/w, consisting of four elements: light and non-light, sound and silence, 24 x 24 x 16 frames."

• From an interview with Peter Kubelka, Electric Sheep magazine, April, 2013:

"Arnulf Rainer is the logical consequence of my previous film travels, so to speak. It’s like when Schönberg started 12-tone music: he didn’t invent it as people always say, rather it was a logical consequence of musical history up to that moment that opened the door to 12-tone music. In the same way, Arnulf Rainer uses the most simple and essential elements that constitute the medium of cinema, namely light and the absence of light, sound and the absence of sound. These four elements are the bare essence of cinema, you cannot go beyond that."

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kangding Ray, Solens Arc (Raster-Noton, 2014)

• Listen: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrUT2ip4hq471fHz9ivbjcsKUx1rKiZ6S

• Excerpted from a review by Daniel Petry (Resident Advisor) http://www.residentadvisor.net/review-view.aspx?id=14413:

Four "arcs," each comprising several tracks, make up the album—perhaps partly to honour the vinyl format, judging by the way each arc occupies one side. But Letellier knows where the concept's influence should end. He uses it merely as a framework, and the arcs' trajectories feel expressive rather than calculated. "Serendipity March" begins the first arc with sparse and murky kicks. "The River" provides an interlude before the driving techno of "Evento." The next sequence starts and ends with beatless passages, and has the whirring stomp of "Blank Empire" in the middle.

Just as each arc has a trajectory, so too does the album as a whole. It starts with the anticipation of the first arc, goes through an evanescent second and climactic third, finally concluding with the fourth arc, which feels like the epilogue to a tragedy. How Letellier achieved this layered format has, no doubt, something to do with his iterative production process, during which the tracks are repeatedly adjusted to realise an overall schema.

0 notes

Photo

Francesca Woodman, Untitled (c. 1975–1980)

• http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/woodman-untitled-ar00357

Woodman has carefully balanced a door at an unusual angle across the room, and hidden herself underneath creating an unsettling sense of claustrophobia. This image is from a series of photographs using doors as props, made while a student in New York. Alone and naked, she seems vulnerable, as she undertakes a voyage of personal self-exploration. The unusually placed items and desolate setting in this photograph create a mystical, transcendental quality in the tradition of Surrealism. The precariously placed, heavy object bears an uncanny resemblance to Richard Serra’s sculpture 'Strike (for Roberta and Rudy)' (1969-71).

0 notes

Photo

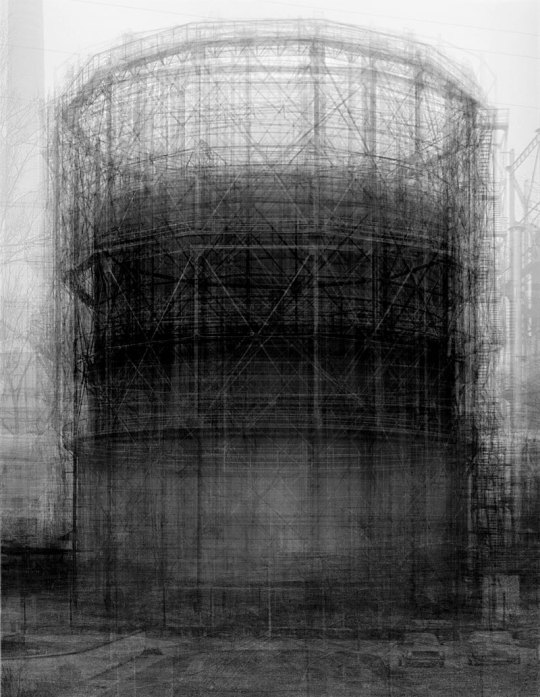

Idris Khan, Homage to Bernd Becher (2007).

• http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/collections/collection-online/artwork/21637

Idris Khan creates densely layered composite photographs by superimposing seminal cultural artifacts such as musical compositions by Beethoven, texts by Nietzsche, or paintings by Caravaggio. While recalling the appropriation strategy of artists like Sherrie Levine who sought to critique the notion of originality by photographing other artists' work, Khan's composites are even more pronouncedly ambivalent in relation to their subjects. On the one hand they enact a kind of destruction by blurring the source materials to the point of almost complete illegibility, but at the same time, they embody—and pay tribute to—the sheer labor and singular vision of the original creators. Khan has repeatedly turned to the work of 20th-century photographers who have themselves explored the notion of the archive, including Bernd and Hilla Becher, a husband-and-wife team known for their decades-long project of documenting various industrial structures, such as water towers and blast furnaces. Khan's condensation of whole bodies of the Bechers' work into single images underscores its obsessive, serial nature. The resulting ghostly palimpsests also suggest a melancholy reminder of the passage of time—one which is especially suitable in this context, given that most of the industrial-era structures the Bechers catalogued were on the brink of extinction. This particular work was made shortly after Bernd Becher's death in 2007.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Jiri Ruzek, So Heavy (2012).

• http://www.jiriruzek.net/photogallery-2012-photographs.html#So-Heavy

0 notes

Photo

Antoni Tàpies, Superposition de matière grise (1961).

• http://www.museoreinasofia.es/en/collection/artwork/superposition-matiere-grise-superimposition-grey-matter

Throughout his extensive trajectory Antoni Tàpies engaged in an unceasing inquiry into different realms of creation—painting, sculpture, graphic works and writing—thus forming a singular identity whose projection and influence made him a referent for subsequent generations of artists. From his initial figuration in late Surrealist style he would move in the late 1950s to the creation of highly material works. In these pieces Tàpies manipulates the density of the support medium with incisions, chipping, graffiti and collages, treating it as an open space, as if it were a wall. Physical presence, such as that materialized in Superposition de matière grise (Superimposition of Grey Matter), distinguishes this canvas-wall from the Western tradition of canvas-window. The experimentation shown by this work in this regard is an important step towards his later conjugation of other materials, textures, signs, objects and ordinary motifs that heighten the presence of the real and reflect the artist’s interest in the physical transformation of the elements. The works by Tàpies in the Museo Reina Sofía collection give a clear idea of the different stages of his oeuvre, which offers a reflection on the nature of images, expressed in a complex language of symbolic origin and a constant vindication of material.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Silueta Series), (1978).

• http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/collections/collection-online/artwork/5221

Spanning performance, sculpture, film, and drawing, Ana Mendieta's work revolves around the body, nature, and the spiritual connections between them. A Cuban exile, Mendieta came to the United States in 1961, leaving much of her family behind—a traumatic cultural separation that had a huge impact on her art. Her earliest performances, made while studying at the University of Iowa, involved manipulations to her body, often in violent contexts, such as restaged rape or murder scenes. In 1973 she began to visit pre-Columbian sites in Mexico to learn more about native Central American and Caribbean religions. During this time the natural landscape took on increasing importance in her work, invoking a spirit of renewal inspired by nature and the archetype of the feminine.

By fusing her interests in Afro-Cuban ritual and the pantheistic Santeria religion with contemporary practices such as earthworks, body art, and performance art, she maintained ties with her Cuban heritage. Her Silueta (Silhouette) series (begun in 1973) used a typology of abstracted feminine forms, through which she hoped to access an "omnipresent female force."¹ Working in Iowa and Mexico, she carved and shaped her figure into the earth, with arms overhead to represent the merger of earth and sky; floating in water to symbolize the minimal space between land and sea; or with arms raised and legs together to signify a wandering soul. These bodily traces were fashioned from a variety of materials, including flowers, tree branches, moss, gunpowder, and fire, occasionally combined with animals' hearts or handprints that she branded directly into the ground.

By 1978 the Siluetas gave way to ancient goddess forms carved into rock, shaped from sand, or incised in clay beds. Mendieta created one group of these works, the Esculturas Rupestres or Rupestrian Sculptures, when she returned to Cuba in 1981. Working in naturally formed limestone grottos in a national park outside Havana where pre-Hispanic peoples once lived, she carved and painted abstract figures she named after goddesses from the Taíno and Ciboney cultures. Mendieta meant for these sculptures to be discovered by future visitors to the park, but with erosion and the area's changing uses, they were ultimately destroyed. Like the Siluetas, these works live on only through the artist's films and photographs, haunting documents of her ephemeral attempts to seek out, in her words, that "one universal energy which runs through everything: from insect to man, from man to spectre, from spectre to plant, from plant to galaxy."

—Nat Trotman

1. Ana Mendieta, quoted in Petra Barreras del Rio and John Perrault, Ana Mendieta: A Retrospective, exh. cat. (New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1988), p. 10.

2. Ana Mendieta, "A Selection of Statements and Notes," Sulfur (Ypsilanti, Mich.) no. 22 (1988), p. 70.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

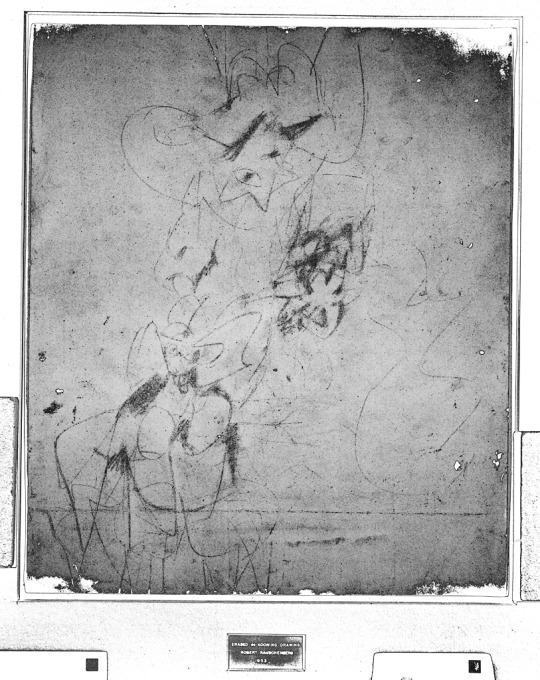

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953).

• http://www.sfmoma.org/explore/collection/artwork/25846/research_materials/document/EDeK_98.298_002#ixzz35jBXeMOC

This infrared unprocessed scan of Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) was made in 2010 as part of an advanced digital imaging effort aimed at learning more about the drawing by Willem de Kooning (1904–1997) that Rauschenberg erased. The infrared light revealed subtle traces of the original graphite and charcoal marks that remain on the sheet.

0 notes

Photo

Francis Bacon, Untitled (Crouching Figures), (1952).

• http://www.indielondon.co.uk/Events-Review/bacon-and-daumier-side-by-side-at-the-courtauld-gallery

Untitled (Crouching Figures) is one of Bacon’s most important works from the early 1950s, a period when he was emerging as the leading British painter of his generation. It is one of a group of works in which nude figures are paired in sexually charged homoerotic compositions.

In the post-war world of the 1950s, Bacon’s revelation through his paintings of the potentially destructive potential of human desire resonated particularly strongly.

0 notes

Photo

From the first sequence of images of the moon's dark side, taken by the Soviet Luna 3 probe in October, 1959.

• http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/imgcat/html/object_page/lu3_3.html:

The Luna 3 spacecraft returned the first views ever of the far side of the Moon. The first image was taken at 03:30 UT on 7 October at a distance of 63,500 km after Luna 3 had passed the Moon and looked back at the sunlit far side. The last image was taken 40 minutes later from 66,700 km. A total of 29 photographs were taken, covering 70% of the far side. The photographs were very noisy and of low resolution, but many features could be recognized. This is the first close-up view of the Moon returned, taken with the narrow angle camera. This image is centered at 20 N, 105 E, the dark region below and left of center is Mare Smythii, the bright crater above and left of center is Giordano Bruno. The Moon is 3475 km in diameter and north is up.

• http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/masterCatalog.do?sc=1959-008A:

Luna 3, an automatic interplanetary station, was the third spacecraft successfully launched to the Moon and the first to return images of the lunar far side. The spacecraft returned very indistinct pictures, but, through computer enhancement, a tentative atlas of the lunar farside was produced.

• http://www.wired.com/2011/10/1007luna-3-photos-dark-side-moon/:

Luna 3′s mission objective was to provide the first photographs from the moon’s far side. To achieve this, the probe was equipped with a dual-lens 35mm camera, one a 200mm, f/5.6 aperture, the other a 500mm, f/9.5. The photo sequencing was automatically triggered when Luna 3′s photocell detected the sunlit far side, which occurred when the craft was passing about 40,000 miles above the lunar surface.

Luna 3′s camera took 29 photographs over a 40-minute period, covering roughly 70 percent of the moon’s far side. The photographs were developed, fixed and dried by the probe’s onboard film processing unit. Seventeen images were successfully scanned and returned to Earth on Oct. 18, when Luna 3 was in position to begin transmitting.

Although the low-resolution images had to be boosted by computer enhancement on Earth, in the end they were good enough to produce a tentative map of the far side, no longer dark to human knowledge. Among the identifiable features were two seas, named Mare Moscovrae (Sea of Moscow) and Mare Desiderii (Sea of Dreams), and mountain ranges that differed starkly from those on the side of the moon facing Earth.

0 notes