Text

Nothing Ever Lasts Forever

“Everybody Wants to Rule the World” (1985)

Tears for Fears

Phonogram / Mercury Records

(Written by Roland Orzabal, Ian Stanley, Chris Hughes)

Highest U.S. Billboard Chart Position – No. 1

I would suggest that what makes a song truly memorable, rather than its intention or craft, is the special, unidentifiable magic that allows the listener to enter into the feeling of it. The Police could sing “De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da” in 1980, and by the end of the song, one knew what they meant, kind of. In pop music, “kind of” is good enough. Such is the moment of what is arguably Tears for Fears most enduring song, “Everybody Wants to Rule the World”. In an album full of big songs (Songs from the Big Chair), and portentous messages (“Shout”, “Mothers Talk”, “The Working Hour”) as well as a gigantic, bombastic love opera (“Head Over Heels”), it was the last effort to be recorded, the album being short one song (the final only 8 tracks), and inspired by two chords Roland Orzabal kept playing over and over during down studio moments. Paired with an idea of a song originally entitled “Everybody Wants to go to War”, spurred on by producer Chris Hughes (a major contributor to the sound and feeling of the record, a masterpiece of old fashioned layered studio sound), and introduced by a sparkling synthesizer coda devised by keyboardist Ian Stanley, the song was recorded in a week (the shortest of any they attempted), was not much loved by the two singers, and then indeed took over the world.

Tears for Fears where formed by Roland Orzabal (Roland Jaime Orzabal de la Quintana) and Curt Smith in Bath, Somerset, England in 1981, after deciding to leave their first new wave band, Graduate. They were barely 21 years old when their very first record, The Hurting, debuted in 1983. The record was an immediate success, with the single “Mad World” charting at No. 3 in the UK, and they were almost immediately very famous. The Hurting was never a record I personally warmed to, not being a hit in the US in its time, and rather overlong and same-y in its synth sound (although I appreciate that to many this is sacrilege, and that they will want me strung up). The general outlook and themes of the band’s two main performers, based on Arthur Janov’s primal therapy/primal scream, was extremely heavy-handed, if sincere, and weighed the album down. It is apropos that when they finally met Janov later in the 1980s they were disillusioned by the fact that he had “gone Hollywood” and that he asked them to help write a musical based on his theories for him.

Songs from the Big Chair was to be a continuation of the same themes of lost childhoods (the title taken from the book and television movie “Sybil”, starring Sally Field, and the big chair being the safe chair in therapy where she could let her multiple personalities appear and subsequently sort out her traumatic past), but rather organically the record moved away from pure synth sounds and into standard instrumentation. In fact, I had not appreciated how much of a guitar, bass, and drums record it is until renting the Classic Albums episode on the making of the record; it is indeed full of gigantic guitar solos, lonely sax, thundering drums, and on “Head Over Heels”, the piano (!) as the driving instrument. The synth work in it (mostly by Stanley) is beautiful and atmospheric, but the soul of the album is in the studio space commandeered by Chris Hughes, as well as the slow and methodical layering of sound that makes the record so special and successful.

Management, being nervous of the insular themes the two main band members, were committed to, begged for, a single, a “driving song”, something that would inspire the listener to roll down the car window and hum along, and perhaps Chris Hughes knew this when he pushed them to flesh out the song. According to the documentary it was one accident after another: Orzabal’s overly strong singing style naturally suggested that Curt Smith take the lead, which brought a wistfulness to it; the lyrics, cobbled together, were snatches of blurry ideas only tangentially related; the shuffle beat of the song, rather than being driving and ambitious like the rest of the album, was subtle and dreamlike; and the very throwaway nature of the track lead to a kind of gentle creativity. “Shout”, the first big single they recorded during those sessions, had set the tone of the record for Hughes, but it was “Everybody” that is perhaps the lasting achievement from the LP. With the droning synthesized voices in the back of the track, the synth sounds, wonderful guitar (yes, including a blazing solo), and the mysterious blending of their two voices, it immediately invokes “that” year when you hear it, perhaps even the entire decade, by not being exactly representative of the band’s sound and purpose. Wistful and ponderous, the song has endured. We all know that “Shout, shout, let it all out” is the real credo for the two of them, but “Everybody Wants to Rule the World”, like the proverbial tortoise, snuck up from behind their giant themes to deliver their message much more softly than either of the two very emotive singers could ever have intended.

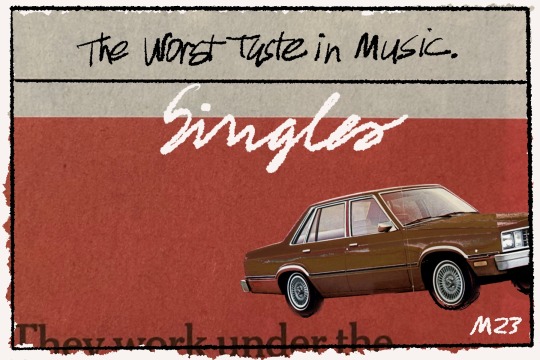

Scenes from the video for "Everybody Wants to Rule the World", shot in Los Angeles, and directed by Nigel Dick, in 1985.

Don’t get me wrong—Songs from the Big Chair is indeed a masterpiece, each track one gem after another, and as a record, a very solid gestalt. Mostly it is a beautiful and mysterious album, one I have never tired of, and entirely deserving of its fame. Sadly, the relentless touring of the album (and their relative very young ages) ruined the relationship for Roland and Curt, and after the long, overblown production for the follow up LP The Seeds of Love (which took three long years to record, so obviously difficult it was to follow Big Chair) that they split up in 1991, and remained estranged for nearly 10 years, with Roland recording for the band alone. With their dour, pouty looks and fisherman’s sweaters, it is not clear that either band member ever actually wanted to rule over anything, but fame obviously had different plans for them. Considering the single today, not understanding exactly what “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” alludes to has ironically made the song even more persistent as a statement; beyond the gentle suggestions of the music, one cannot help but think of it as either a forecast of the greed of its era, or perhaps as the dream of a dream for the 1980s.

However, Tears for Fears' most successful single is still miraculously casting that very same spell it did in 1985. A mood will always be a mood.

***

Chris Hughes, instrumental as producer for the sound of Big Chair, co-wrote “Everybody Wants to Rule the World”. He began his career as the drummer for Adam and the Ants, and produced the band’s very influential Kings of the Wild Frontier album in 1980. He was the producer of both The Hurting and Songs from the Big Chair, and co-produced Peter Gabriel’s “Red Rain” from the album So.

Roland Orzabal and Curt Smith are both 62 years old.

Producer Chris Hughes is 70.

Ian Stanley (keyboardist) is 67. He was unhappy with the direction of Tears for Fears’ The Seeds of Love (1989), which he considered lightweight by comparison, and split from the band, eventually working with many artists, including Howard Jones on that famously heavyweight album Cross That Line (1989), and which produced his comeback single “Everlasting Love” (No. 12 in the US).

Roland and Curt reunited in 2001 and recorded tracks for Everyone Loves a Happy Ending, promising a follow-up.

Eighteen years later, in 2023, The Tipping Point was released to near universal praise and chart success, their most personal and cohesive record as a duo since Songs from the Big Chair. The scream was back, more plaintive than primal, and much more suited to their age and experience.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Electro-Pop

“A Little Respect” (1988)

Erasure

Mute/Sire Records

(Written by Vince Clarke, Andy Bell)

Highest U.S. Billboard Chart Position – No. 14

A sublime crescendo for synth pop music, the throbbing percolation of Erasure’s “A Little Respect” had many precursors to build upon. Way back in 1972 there was the novelty hit “Popcorn” by the band Hot Butter (!), which was apparently by a collection of serious musicians and prominently featured the Moog synthesizer. I remember it well (and fondly) as perhaps the first totally electronic pop song I had ever heard. A No. 5 Billboard hit, and a No. 1 smash all over the world, it was an example of the appeal of synth songs outside of the disco (or dance music and the clubs). It showed that a lot of people really loved electronic sounds before the ghettos of disco, house and techno emerged and unfairly maligned the music as a cultural signifier in the United States, meaning black, hispanic, or gay (according to the year you are considering).

The next record I would mention is M’s “Pop Muzik”, a US No. 1 from 1979 that I actually went out and purchased, another purely electronic moment that lived outside of the dance floor and more toward the pleasure of the sounds it was making: it was vaguely new wave, euro, but certainly was not disco. It had the hallmarks of a novelty record as well (a one hit wonder over here for sure), with no success in the states for the album featuring it (New York • London • Paris • Munich), even though the musician Robin Scott was well respected, and the record featured two band members that later joined the funk fusion pop band Level 42 (more on them another day) and that apparently it featured the handclaps of one David Bowie, who had dropped by the studio.

Vince Clarke began his career as the main songwriter and band member of the British new wave band Depeche Mode in 1981. Before he left them (after only one album, Speak and Spell), and before they went all dark and sado, he helped them pump out three infectious slices of electronic bubble gum: “Dreaming of Me”, “New Life”, and the 80s chestnut “Just Can’t Get Enough” (which, okay, could be seen as a precursor to a darker disposition), all of which have lasted as classic electronic pop songs. I don’t think being in a band suited Vince, for he quickly parted ways to pair with smoky blues contralto Alison Moyet to form the band Yazoo, and they went on to record the seminal electronic album Upstairs at Eric’s, which inspired art students and moody teens everywhere, then and now, and produced the classic and much-sampled song “Situation”, a tireless dance floor staple with a ridiculously catchy synth hook by Clarke. Alas, after only two albums with Alison (including the follow up, You and Me Both), the duo split up, apparently because of clashing personalities, with each member having a conflicting concept for the direction of the band. It really was a shame; neither one was ever cooler.

Cover art for the Depeche Mode single "Just Can't Get Enough"

Alison Moyet and Vince Clarke of Yazoo (shortened to Yaz in the US) in 1981.

Vince may have found his ideal partner in singer and songwriter Andy Bell when he formed Erasure. Clarke has always professed his attraction to the fact Andy identified as gay (Clarke is straight): he found this idea of a partner more intriguing. Andy Bell had a voice very similar in tone and delivery to Moyet; what he didn’t have was any sort of coolness at all, being wildly bombastic and emotive instead. Their first records did little for me, despite featuring Clarke’s classic and beautiful synth work; something just didn’t click—it seemed like a less effective version of Yaz. Enter producer Stephen Hague, who, having smoothed out all of the harsh Bobby Orlando productions to create the Pet Shop Boys’ seminal debut Please, did the very same for Erasure and their breakthrough album The Innocents. I was in art school, in a life drawing class, when I met another male student very unlike me listening to it on his Aiwa Walkman player. I asked what was so good, and he told me it was Erasure, and that he couldn’t stop listening to it. Before I knew it “A Little Respect” was everywhere: all over the radio, all over the clubs. The hook for Clarke was back – the first electro piano chord sounds are irresistible, and Andy comes in plaintive, not bombastic, and suddenly reveals more of a psychological clarity in his lyric writing; all in all, the record is a beautiful balance between hot and cool, up and down, brimming, swelling to a near crescendo, but never overflowing. The synth keyboards have a baroque interplay, with contrapuntal tensions underneath the melody, and thinking about its long life and fame I can appreciate it as such a far cry from the pop novelty songs it sprang from, first from “Popcorn”, to the debut for Depeche Mode, then to Yaz, and beyond— as an ever-deeper example of what an electronic record could accomplish. It may be true that it took Erasure a bit of time to settle in and achieve this because Vince Clarke had already gone through so many stages as a pioneer. He really is one of the true architects of the electro-pop sound, and along with Andy’s new found maturity as a writer and singer, instead of getting a little respect, they garnered a whole lot of it. It may have never made it to the top, but “A Little Respect” has survived as a classic of the genre, and is impossible not to bellow along to in any bar or pub you hear it playing in. Come on. I know you’ve done it. And the drunker, the better.

*

The Laugh Heard ‘Round the World:

Yaz (which is how I know them) was shortened from the British Yazoo to avoid a legal conflict with a little known rock band in the USA.

The song “Situation” was recorded on the fly as a B-side to the lead single “Only You”, and was remixed again and again, taking over the dance charts. Alison Moyet’s opening laugh effect has been sampled on subsequent dance tracks many times. The “laugh” echo can be heard on the giant hit “Macarena” by Los Del Rio, Samantha Fox’s “I Wanna Have Some Fun”, Deee-Lite’s “What is Love”, and C+C Music Factory’s “I’m Gonna Make You Sweat”, to name only a few. Alas, the sound of Alison laughing only brings you back to wanting to hear “Situation” again.

Erasure, once a pale shadow of Yazoo, achieved a golden mean with The Innocents, it’s excesses smoothed and corrected by what I believe is the sure hand of Stephen Hague, and produced another hit in the US with “Chains of Love” (Billboard No. 12). But if you want to hear where Erasure was headed, progress to their next singles, “Stop!” and “Drama!”, both of which went top ten in the UK, but nowhere over here. I think these songs are what the band is really all about, as dramatic and over-the-top as their titles would suggest.

Erasure have released 19 studio albums to date.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hits and Misses

“I’m So Excited” (1982)

The Pointer Sisters

Planet Records

(Written by Anita, June, and Ruth Pointer, Trevor Lawrence)

Highest U.S. Billboard Chart Position – No. 30 (1982)

Highest U.S. Billboard Chart Position – No. 9 (1984-85)

The Pointer Sisters, a trio who exploded onto pop radio in the years 1984-1985 with near ubiquity, have a legacy that has strangely vanished. Once as big as Madonna, Prince, and Michael Jackson, one might ask: where did they go? They sizzled in 1984 on the soundtrack for the most successful comedy of the year (Beverly Hills Cop) with the excellent electro thump of “Neutron Dance” and dominated the charts for years with the evergreen hits “Jump”, the robotic soul of “Automatic” and the re-released version of the 1982’s “I’m So Excited”. They were perfect examples of 80s new wave soul, and they were everywhere, on every part of the dial—mainstream from pop to soul. And then they were gone, a vestige of the 80s rather than a mainstay, yet with a slew of uncanny singles that still play over and over again, phantoms from a permanent era. So—who were the Pointer Sisters?

The soundtrack to Beverly Hills Cop, 1985.

They were, eldest to youngest, Ruth, Anita, Bonnie, and June, all born in Oakland, California, and signed to Atlantic Records in 1971 after doing session work. They scored a hit with Allen Toussaint’s “Yes We Can Can” in 1974, a delightful nod to the retro 1940s (which included their costumes), a style choice even more delightfully underlined in the cover of Dizzy Gillespie’s “Salt Peanuts”, a manic jazz pop pastiche from their 1975 follow up. I remember seeing them on the Carol Burnett show that same year and wondering where they came from even then; with the longer skirts, block heels, and wide brimmed hats with cherries pasted onto them, they seemed like a mirage. Clearly no novelty act (all of them equally talented) they presented as strangely anachronistic for any era; this thought would be supported by some significant cultural moments to come, like winning a country music award for the 1975 song “Fairytale” (written and performed by Anita) as well as being the first black women to ever play at the Grand Ole Opry. Nevertheless, as refined and talented as they were, they never tapped into mainstream radio, or the zeitgeist. On that 1975 LP That’s a Plenty, “Fairytale”, in a convincing country riff, is immediately followed by a lush interpretation of the standard “Black Coffee”, establishing that this was an act that would be very hard to pin down. They were almost too good.

Bonnie would soon leave the group to go solo, making the sister act a trio. To be honest the sisters seemed to join and quit the band so band many times it is hard to keep up, but the classic trio would end up as Ruth, Anita, and (baby) June. The real change in the sisters’ fortunes would be a new focus on making mainstream pop hits. Enter Richard Perry, a wildly successful producer known for rock solid songs, expensive “A” records, studio perfection, and giant hits (for example Carly Simon’s “You’re So Vain”). Over the next three years with Perry, The Pointer Sisters scored three evergreen, monster singles: “Fire” (written by Bruce Springsteen), “He’s So Shy”, and “Slow Hand”. “He’s So Shy” would predict a smart direction for them: light, airy radio fodder supported by gutsy, well-trained voices and acrobatic performances. The veneer was pop, but the records were soul, and by now The Pointer Sisters knew they could deliver the massive hits they deserved.

1983’s Breakout was just that, the atypical Richard Perry record that traded his classic organic studio sound craft for synthesizers. The first tame midtempo single, “I Need You” (R&B No. 13) barely scraped the Top 40, but the next one, “Automatic” (No. 5), evidenced some very new choices. Suddenly, miraculously, the group came into complete focus: a white hot, current, almost futuristic sound (featuring the low contralto of Ruth Pointer), clearly inspired by Prince, but sounding like no one else. The hits came fast: “Jump” (No. 3), the re-released “I’m So Excited” (No. 9), “Neutron Dance” (No. 6), and “Baby, Come and Get It” (No.44, and a personal favorite). Not since Wham’s Make it Big has a record title been this prescient. Although no song hit the top spot, these where long charting hits, and “Jump” was the best-selling dance record of 1984, supported by a ubiquitous video, and the album selling millions. And then, in a flash, their dominance was over. “Dare Me”, in 1985, was a hit (No. 11 Pop, No. 6 R&B), but can you hum it?

No one would ever call The Pointers anything but wildly successful (talent and fame alike), with a long rich history, full of variety. I wonder why it is that their disappearance, and now a ghostly absence, continues to surround them as artists. It is rather akin to the fantastic apocalyptic torn fashions they were once swathed in on the Breakout cover, forever frozen in their moment of being in fashion, only to be discarded for the next one. I feel like we took them for granted, but I also sense a certain aloofness in their mastery of so many styles and in their range. (One only has to try to listen to 1975’s That’s a Plenty to admire their deluxe appropriation of American musical traditions and styles, but to be honest, I always turn it off, a little overwhelmed.) The real sisters, if they will please stand up, can surely be found on their two least pretentious records, So Excited! (‘82) and Breakout (‘83). Putting their refined soul voices into an electro vacuum somehow suited their talents the best. These albums are still very sophisticated; instead of verisimilitude the records had one eye on the charts, and the other on authenticity: they were shiny, expensive toys, and delightfully wrapped in tinsel.

----

One can certainly paint a very different picture for the career of the Pointers from an R&B chart perspective, where they charted differently, and with perhaps a more faithful fan base. In fact, their only No. 1 single on any chart was R&B, 1975’s “How Long (Betcha Got a Chick on the Side)”, as compared to its peak at No. 20 on the Pop chart—a Philly funk workout that seems rather forgotten today. I would still maintain that they did best on mainstream radio, sacrificing almost nothing of their true talents or style, and wouldn’t describe them as a crossover act. The Pointers wanted hits, however much they experimented otherwise, although the length and diversity of their career will also always be worth exploring through their catalogue.

Here, as a sample, is the delightful and bizarre “Salt Peanuts”.

June Pointer, who also suffered from drug addiction, died of cancer at aged 52 in 2006.

Bonnie Pinter passed away in 2020, aged 69.

Anita Pointer passed away in 2022, aged 74.

Ruth Pointer, the eldest at 77, is still with us.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A New Cool

“West End Girls" (1985)

Pet Shop Boys

Parlophone Records

(Written by Tennant/Lowe)

Highest U.S. Billboard Chart Position – No. 1

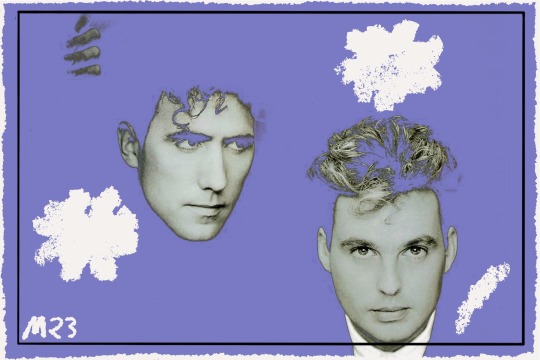

There are two lines of thinking concerning the debut pop single for the seminal electronic pop band Pet Shop Boys; one, that the song is atypical of all of the hits they would ultimately create (and are still creating over 30 years later), and the other is that this is their signature song. I am of two minds, that it is at once very them, and conversely not them at all; in some ways their first hit was a makeover of the band, whether by design, or not. It is undeniable that in 1986 it was enormously successful, an evocative ear worm, and that the single introduced the strangely beautiful tenor voice of singer Neil Tennant, and ushered in one of the greatest pop duos ever.

Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe met in a hi-if shop in London on Kings Road in Chelsea in 1981, and discovering a mutual love of electronic music, formed a band. Tennant was at that time an assistant editor at Smash Hits magazine, and Chris a college student studying architecture. Immediately, they began writing songs together in Neil’s bedsitter apartment (which I believe translates as a studio in the US). They signed with American producer Bobby O (who oversaw rather crude Miami-tinged 80s dance music) in 1984/85; together with him they produced for the first time many of the songs that would appear on their debut Please, and the follow-up LP, Actually. “West End Girls” was released in 1985 as a 12” disco version that was much cruder and sparer; it was a minor hit in Europe and a “Screamer of the Week” on the influential 80s radio station WLIR in Long Island, New York (who's djs had a nose for new wave talent). Nevertheless, it sank, and they spent the next year extricating themselves from Bobby O and signing with EMI, relinquishing to him some of the future royalties on many of the soon-to-be famous songs they had already written, including “West End Girls”, “Opportunities”, and “It’s A Sin” (all of which were re-recorded and eventually went top ten in the United States). It would seem that the Imperial phase for any great band must always begin with a lawsuit.

“West End Girls” was re-released by the band in late 1985 in a much different version produced by Stephen Hague, and it immediately conquered the world, selling 1.5 million copies. Where the Bobby O version squawked and squealed and sounded dated even then, this new track slithered on to the airwaves with a newer, more insinuating quality. Rather than a club banger, this was now a highly suggestive track, with droning, floating synths, every effect modulated downward into an expression of cool detachment. It was an important single not only in introducing this idea of bored aloofness from the duo, but also by permanently stamping them with the image. No matter how hard they would try in the future to produce bombast (say, on “It’s a Sin”, a truly bezerk pop hit) they would be forever labeled as sardonic, stand-offish, bored, or sarcastic. These are words that really translated into one idea for me: that they were actually gay, and smart, and therefore happy to play along with any narrative the public chose for them as long as people continued to buy their records. The song’s lyrics, written by former history major Tennant, apparently reference Eliot’s “The Waste Land”, which sounds hilariously high-toned, but for the then 19 year old that first experienced it, it was clearly a coded story of gay boys clubbing on the wrong side of town, because the gay bar is inevitably on the wrong side of town, and that perhaps West End Girls is a clever wink at describing gay men crossing over. On top of all of these suggestions was a very fey British man successfully talk-rapping lyrics (a rap I can to this day successfully recite), telling a story with no obvious conclusion, because, well, you know. It is a coded song about a coded world. And while the Pets didn’t invent the electronic pop song, like couturiers they certainly tailored it to the measure of some very strict gay signifiers, and when I fell in love with the hit (and the band) I was already acquainted with those ideas and understood them instantly. Of course, I did not experience the duo as detached; instead, they were stylistically and artistically brilliant, and their songs were clever, propulsive, and unique.

Please as an album can be examined as a cohesive slice of queer nightlife in the 1980s: escaping to the city (“Two Divided by Zero”, “Suburbia”), sneering at society (“Opportunities”), fighting oppression (“Violence”, “I Want a Lover”), and, finally, reconciling to life and love, whatever that might mean (“Later Tonight”, “Love Comes Quickly”, “Why Don’t We Live Together?”). I am sure “West End Girls” does reference “The Waste Land”, but somehow, just perhaps, Neil, the master of collage, is actually speaking more allusively to the mating habits of the male homosexual circa 1985. Chris Lowe, for his part, made absolute certain that the songs would be played were they belonged, which was in the club, his complete obsession in every way; the electronic sounds he produced are essential to the texture of what Pet Shop Boys ended up doing better than anyone else, which was to document gay lives by dropping clues and signals to fantastic disco music while leaving out the specifics. And this is possibly why the original Bobby O version was so awfully wrong, and not really them: the duo must have discovered that they didn’t need to bang bang bang, that they could be better than that. In fact, they actually didn’t need Bobby O at all; they could conjure up these subtle and delicious scenes all by themselves.

Sadly, Bobby O still got the money. Kind of just like a Pet Shop Boys song, isn’t it?

A little cynical, but true.

-

*The title of Please, which I always found entertaining, I imagined was a reference to gay men chastising one another with "Oh, Please", or "Girl, Please." This has never been substantiated. Instead, Neil was quoted as saying it was a little joke, so when a customer asked for it, they would be forced to say I would like Pet Shop Boys, Please. Hmmm. Regardless, this would still qualify as a double entendre.

-

Dropping a hairpin (verb, gay, archaic slang term): to reveal one's sexual preferences by dropping broad hints; thus keep your hairpins up, and maintaining a 'normal' mask.

Who, who wants a cocktail? (“Opportunities (Reprise)”)

Someone spread a rumor. Let’s run away. (“Two Divided By Zero”)

In every city, in every nation, from Lake Geneva to the Finland Station. (“West End Girls”)

You may not always love me

I may not care

But intuition tells me, baby

There's something we could share

If we dare, why don't we? (“Why Don’t We Live Together?”)

And you wait 'til later, ‘til later tonight.

'Cause tonight always comes. (“Later Tonight”)

Neil Comes Out

In the early 1990s, Jimmy Somerville, formerly of the very out, gay 80s band Bronski Beat, accused Neil and Chris of Pets Shop Boys of exploiting gay culture for career purposes, and of not putting anything back.

Neil came out officially in 1994, and commenting in print on the matter, said that he resented anyone telling anyone how out they should be, or just what constituted a “contribution” to gay culture:

“I do think that we have contributed, through our music and also through our videos and the general way we’ve presented things, rather a lot to what you might call ‘gay culture’. I could spend several pages discussing the notion of ‘gay culture’, but for the sake of argument, I would just say that we have contributed a lot. And the simple reason for this is that I have written songs from my own point of view…”

He pauses again. “What I’m actually saying is, I am gay, and I have written songs from that point of view. So, I mean, I’m being surprisingly honest with you here, but those are the facts of the matter.”

Having finally got all that off his chest, Neil Tennant pours himself a glass of mineral water and takes his sweatshirt off. He is looking distinctly pink around the gills. Maybe it’s the effect of suddenly admitting that for all these years he has been singing nothing but the truth. Or maybe it’s just the unbearable heat in here. “Well,” he says, in a voice which carries a distinct [air of]‘moving swiftly on’, “what’s your next question?”

Source: Neil Tennant in Attitude Magazine, 1994

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Have a Nice Day: The 1970s

“Alone Again (Naturally)” (1972)

Gilbert O’Sullivan

Epic Records

(Written by Gilbert O’Sullivan)

Highest U.S. Billboard Chart Position – No. 1

To think that only yesterday

I was cheerful, bright and gay

Looking forward to who wouldn't do

The role I was about to play

But as if to knock me down

Reality came around

And without so much as a mere touch

Cut me into little pieces

Leaving me to doubt

Talk about, God in His mercy

Oh, if he really does exist

Why did he desert me

In my hour of need

I truly am indeed

Alone again, naturally.

– Gilbert O’Sullivan

Welcome to my childhood. “Alone Again (Naturally)”, certainly one of the most depressing songs ever recorded, was my first most favorite record ever. I remember it playing at the Boys Club of Savannah over the loud speaker in the gym along with all of the other groovy, long-haired country-tinged soft rock oozing out of the airwaves at the time. It is a song about a young man being jilted at the altar, swearing to himself he will throw himself off a tall building soon, and then about the unexpected death of a parent and a mother mute with grief…and I loved it. I would wander around the Boys Club with my own mute, melancholic fantasies of sorrow and loneliness, oblivious that most boys my age were still into Snoopy and Bubblegum music. Listen: it was the 70s—no subject seemed off limits.

The open of the song is Sullivan’s signature broken piano style, something that sounds like a mistake but by being repeated within the song ends up as a very effective method of expressing brokenness itself. Gilbert was Irish-born to a working-class family and moved to England as a child; his actual mother ran a sweet shop and his father was a butcher. He was a natural musician, and intent on pop success he invented a Chaplin-esque, waifish turn-of-the-century affect: suspenders, shorts, a tilted cap. By the time of “Alone Again…” he switched to an even more ridiculous 1920’s college prep look, sporting V-neck sweaters with a large silly G pasted on them. No matter; the songs spoke for themselves, little dour slices of life with old-fashioned melodies and a vintage feel, and proved enormously successful: he was the top star of 1972.

I mention this because it feels as though Gilbert’s catalogue is as lost as his records once sounded. In America he is rarely mentioned (or so it seems to me) even though he had 3 top ten hits in the US (a second single, “Clair”, reached no.2 that same year, followed by a slightly funkier song in 1973 entitled “Get Down” that made it to No.7). He was Grammy-nominated that year for Song of the Year and Record of the Year, along with Roberta Flack (for “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face”) which she won (deservedly) for both. It is astonishing to my adult self that these two records exist in the same universe, much less the same year, Roberta’s record still feeling endlessly modern and fresh, and O’Sullivan’s feeling like it belongs in the Norton Anthology of English Literature instead.

This is not to diminish Gilbert in the least (he is still alive and working and, of course, very famous in Japan, like all the major/minors are). If I happen to hear this record it is just as wonderful as it ever was, and it will still fill the 7-year-old in me with those wistful feelings of chances lost and memories of being jilted, even though my only real tragedies up to that point consisted of finding that the milk had run out for my Cap’n Crunch cereal that morning. And yet I would still find myself wistfully kicking around the empty basketball gym, avoiding all of the other rowdy boys, just waiting around to see what the 70s had in store for me, and surreptitiously absorbing all of those groovy tunes ricocheting across the gym.

_

“Alone Again (Naturally)”, besides being a well-covered and highly regarded song (Nina Simone recorded a version), is notable for another inflection point in history: in 1991 O’Sullivan sued rapper Biz Markie for prominently using the piano break in the Hip hop song “Alone Again”. Gilbert won 100% of the royalties for the rap song, and this would help to establish the industry standard for clearing (and paying for) any sample by another artist, which has changed the music business to this day, for better or for worse.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Closet, Part 1.

“Everything She Wants” (1984)

Wham!

Columbia Records

(Written by George Michael)

Highest U.S. Billboard Chart Position – No. 1

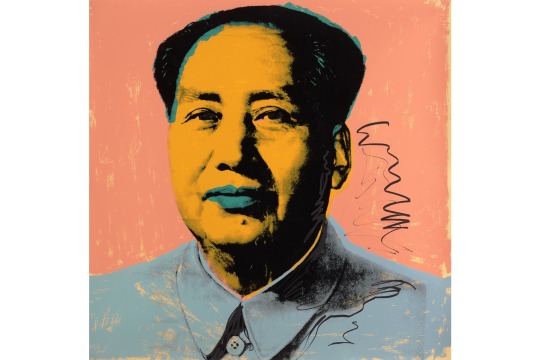

Not since Warhol painted his silkscreens of Mao Zedong in the early 70s had a project as blatantly propagandistic as Wham!, and their second album, Make it Big, appear on US shores. It was a record with its intentions splashed across the LP cover in large, unironic text above the image it was selling: the nubile duo of George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley, hairdos perfectly coiffed, all done up like doe-eyed fashion models in high-end sportswear. Even the colors of the album were strategic: red, white, and blue. Wham! was clearly setting their ambitions straight for the Reagan 80s, and toward US domination.

Andy Warhol, "Mao", 1972, Silkscreen.

Like the Reagan 80s, the ideas behind the first single, “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go”, were as fun, retro and catchy as his signature jelly beans. I wasn’t terribly impressed with the song (first heard over the piped-in radio at the Chick-Fil-A I worked in at in the mall) until I saw the video. There he was: George Michael, costumed in short shorts, wearing a white sweatshirt that screamed Choose Life, hugging himself as he ponied and swam about in a sea of neon colors. It was then that the song really took off for me: George, Andrew, Pepsi and Shirlie, all having a romp, signaling that the New wave was over, and that something much bigger was ahead of us: pure, unadulterated fun. Of course I zeroed in on George, his Greek curls laboriously blown out into a perfectly feathered mane and dyed into the colors of artificial sunshine, and in the pivotal video moment, hugging himself tightly with fingerless cotton gloves, two gold-hooped earrings glittering for the camera. I am telling you, those earrings on George Michael were the gayest thing I had ever seen (not the straight “one” earring, but two), and thereby an annunciation: looking at him, right there on regular TV, I felt reborn.

Make it Big would spawn five top ten singles in the United States (if you count “Last Christmas”, a one-off that would appear as a double A side with “Everything She Wants” in England) and included three US number ones. “Everything She Wants”, which followed “Wake Me”, “Careless Whisper”, and “Freedom”, would be the last to be released from the album, and it was unique in that it did not seem to be cut from the same cloth as the other singles, which were in essence modeled after Motown. It was a song that also did not depend on a video to sell itself (not that they didn’t make one). I was in the bathroom blow-drying a crest into my swing bang when I first heard it on the radio, and I know I must have frozen mid-bang. Something was very different with this track. First and most importantly it was entirely built on a synthesizer, from the Linn drum bongos that open it (George’s rough demo sample was kept for the final product) to the beautiful synth notes; in fact, like “Last Christmas”, the entire song was written and performed on one instrument, a Roland Juno-60, and both songs would be performed solely by George without any other musicians to sweeten it. He wrote and arranged it overnight, with no thought of it being a single until everyone responded to it so well. According to engineer Chris Porter:

"I think this was when George started to realize that if he wanted to, he could do everything himself. He could [just] cut out all these other people and their ideas."

Back in my bathroom, frozen in place, I wouldn’t have perceived any of this. What I was perceiving was something even gayer than George hugging himself in “Wake Me Up”: this new George had a voice speaking directly to me. “Everything She Wants” is a song about a man in an unhappy marriage, an unhappy 80s marriage, to be precise, because the female in question is fixated upon perfection through consumerism. George in the song is projecting the role of the long-suffering woman, and in an act of pure subversion instead plays the hard-working husband who has to pretend that he is fulfilled by having a wife. He is, in essence, bitching about having to play it straight, and in my mother’s bathroom I understood completely that a song dripping in sarcasm about being in a marriage was the queerest (and possibly most liberating) thing I had ever heard in my life up until that moment, the peak, the essence, being when he sings the lines:

And now you tell me that you're having my baby

I'll tell you that I'm happy if you want me to

But one step further and my back will break

If my best isn't good enough, then how can it be good enough for two?

Not only were these priceless, hilariously bitchy lyrics (the song is punctuated with his backing vocals screeching “work!”, “work!”) it directly expresses the reality of a gay man suffering miserably in the closet, and delivers a pungent commentary about the reality of living in the shadows of straight conformity. The most delicious thing about it was the era it was tucked into (with its new rush of bubblegum pop)—if the song had a real message, it was sure to be lost in all of the neon fun. The import was not, however, lost on me.

Looking gay, as Wham! did, does not make you gay. Making fizzy, lush pop songs, in and of itself, of course does not make you gay. Being a male pop duo does not make you gay. After taking over the world, hit after hit, the final No.1 for Wham! in “Everything She Wants” definitely, definitely made me gayer. In sound and vision, it would mark the beginning of George Michael as a real solo act, on the precipice of joining the ranks of the biggest pop stars in the world. Soon, George would have all the fame he could ever desire; sadly, it would prove to be the biggest closet of them all.

Last Christmas, 1984

Written in 1983, recorded in August of 1984, Wham’s “Last Christmas” would of course be announced as a December release (George had performed the song alone in a studio fully decorated for Christmas with engineer Chris Porter to set the mood).

In the UK there is a long history and competitive spirit surrounding a Christmas No. 1 , which meant the hit should be the last to chart for the year. Famous examples of a Christmas No. 1 in the UK would include The Beatles’ “I want To Hold Your Hand” (1963), The Human League's “Don’t You Want Me” (1981) and Pet Shop Boys’ “Always on My Mind” (1987). In 1984, during the filming of Band Aid’s “Do They Know It’s Christmas”, which was produced for famine relief in Ethiopia by Bob Geldof, one can see George Michael lamenting that the song they were recording would surely keep the Wham! track from going to No.1, and he was right. “Do They Know It’s Christmas” won the year, with “Last Christmas” coming in as No.2. He had smiled shyly when he said it, but one could tell he was over it. If George Michael was anything in the 80s, it was ambitious.

In 2006, Michael released a Greatest Hits, Twenty-Five, featuring four new songs, one of which, “Understand”, would serve as a sort of apologia to “Everything She Wants”, imagining the couple 30 years later, and seeing the relationship more from the woman’s point of view.

George always insisted that “Everything She Wants” was his all-time favorite Wham! song, and he performed it regularly in concert.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Look.

“Is There Something I Should Know?” (1983)

Duran Duran

EMI - Capitol Records

(Written by Simon Le Bon, John Taylor, Roger Taylor, Andy Taylor, Nick Rhodes)

Highest U.S. Billboard Chart Position – No. 4

“[It was] completely separate from electronic music or the future…all the fucking Southern New Romantic bollocks. I mean, if we were ever called New Romantics there'd be a fight... 'Am I wearing a kilt? Am I wearing enough eyeliner? Is my shirt frilly enough?' Oh, fuck off!

- Paul McCluskey from Orchestral Manoeuvres in The Dark on The New Romantics

I love the term “across the pond”, which suggests that England, the mother country for the USA, is only a hop and a skip away, when in truth, the spaces between us are enormous. The innovations transferring from one continent to the other, especially with respect to music and fashion, have always had a strange and years-away delay that has been ongoing since the very beginning, as if the ideas were always awaiting the right winds, funding, and large, cumbersome, three-masted ships from the Colonial period to bring them over to us. Part of Modernism is to assume the new world will be changed; part of reality is that the change, as delivered, is much more elusive.

In 1982 the Second British Invasion was brought to the United States in color on MTV, and was ushered in by two very important videos: first and foremost with the complete smash “Don’t You Want Me” by The Human League (an electro masterpiece and forever influential) and then by Duran Duran’s “Hungry Like The Wolf”, their first bonafide, giant US hit. It wasn’t just MTV that had them on heavy rotation, it was nonstop over the airwaves as well: these two songs nearly swallowed up the 1982-83 season for radio. In truth there was so much happening with British artists over here that year it is dizzying to consider; sound and image were delivered with enormous speed, and very persuasively. It was a very rapid musical turnover (and considering my previous thoughts, I know this is ironic; however, a backlog is a backlog.) The only problem for me that year was that I loathed “Hungry Like The Wolf”; this included the song, and the stupid video, in which I believe Simon Le Bon is in animal drag pursuing a female through the jungle, but I can’t be sure: I refuse to look at it again after being forced to 500 times. I was also only mildly interested at the time in “Don’t You Want Me”, after being worn down by its’ endless radio play in the US. However, the invasion had begun.

As a teenager, there was a lot to process in 1982/83: music was now television, and MTV was our god. I wasn’t staying up late to look at the Brits, I was staying up late waiting for Prince to appear in a haze of multi-colored, neon-infused fog spinning around in high-heeled boots to “Little Red Corvette” (an incredible fusion of sound and image). There was a lot to look over: Men at Work with “Who Can It Be Now”, A Flock of Seagull’s “I Ran (So Far Away)” which was HUGE in the states, and even Bowie, the originator, coming back from the dead with the future-forward “Ashes to Ashes” being re-aired (1980). The Vee-jays talked and talked, and we absorbed every scene.

In 1983 Duran issued their 8th single, “Is There Something I Should Know?” straight to MTV in a video directed by Russell Mulcahy, and it was at this moment that I sat up and took notice. Technically the band had already conquered the UK and the US, but it took forever for these ideas to sail my way. Capitol Records was looking for another hit and had the band create this track after their best album, Rio, was already a sensation, and they were starting to work on their third, Seven and the Ragged Tiger (a hilariously late-imperial and overblown, if rather beautiful, mess). For me, watching on TV, this video was my first impression of The New Romantics ever. Even though DD's style had already moved forward into clothes that were more New wave, I could sense the old style running through the images. Mulcahy, a true innovator in music videos, had directed many of Duran Duran’s previous clips, as well as for many other artists (notably Buggles “Video Killed The Radio Star”, MTVs first-ever video broadcast, and most representatively Duran’s “Planet Earth”, which, shockingly, I had missed). His work initiated many of the classic techniques in video: spot lighting, jump cuts, platform stages, empty spaces, slo-motion, breaking glass, fog, bifurcated screens, costumes, nonsense—you name it.

Unbeknownst to me at that time, Capitol tacked this single on to Duran Duran’s first, self-titled debut LP (1981) for the 1983 US re-release, to capitalize on the huge success of Rio’s “Hungry Like the Wolf”. Until this post, I was always confused at the range of style changes and images that we took in from Duran in ’83, and why I assumed this look was from 1981. We were all taking in so much British fashion then it was impossible to sort any of it out. The video, however, was sharp, clean, and brilliant, the clothes still holding a bit of the New Romantic flounce and swagger, but cut leaner, and cleaner; the bandmembers, by now seasoned stars, had clothes, hair and makeup all perfected in an exactitude of knowing postures, and the song was one of their best, and hookiest, with old touches of guitar from their previous work, and with synth-work that looked forward to the next record. But in 1983, I thought that this was vintage Duran.

Fashion is a curiously hard thing to pin down, especially considering the clothes from London and Birmingham in the late 70s and early 80s. I would submit that a classic, classic New Romantic look would be the Duran Duran of 1981: lots of makeup, lots of flounce and ruffles, lots of teased up hair (even a ponytail, here or there). The beginning of the look sprang up alongside of punk (which was anarchic and utilitarian); Bowie and Bolan would be among the New Romantic inspirations. By the time of the 80s things moved quickly, and Malcolm McClaren and Vivienne Westwood’s Sex shop become involved (Westwood’s Pirate collection in 1981—think Adam and the Ants—is a clear expansion of New Romantic fashion); however the Sex shop was also an expression of Punk fashion, and much more avant-garde, so the ideas began to merge and mutate. By 1983, to be called a New Romantic band became an insult (and to these eyes a downright homophobic assault on foppery and artifice) and many bands distanced themselves from the title, if not outright denied it. Even a band like Spandau Ballet (a true New Romantic sensation from the Blitz club in London) moved away from those associations, and began to wear suits. With the Duran of 1983 everything was trimmed down but one could see they were unashamed; if their clothes flounced less, they still had the spirit in them. This was in contrast to the bands that resented the association for whatever reason: ABC, Depeche Mode, The Human League, Soft Cell, Simple Minds, Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark, and Talk Talk. The other band closely associated with it, Culture Club, was fronted by Boy George, whose fashion sense ran from Bowie to Punk. He seemed neither to take offense nor to care what they called him as long as they were looking.

Back in America I was watching all of this late at night on television—too late. Many of these styles had emerged and were already smoldering in the ashes before we could understand or appropriate them here. New wave we got, New Romantic we did not. It did all rather re-flower in the mid to late 80s for us, however. Looking at the back of the vinyl from the offshoot band Arcadia (with three members of Duran, 1985) I would say their old style had returned. Around this period there were lots of brooches and asymmetrical haircuts, lots of layers, and lots of unashamed extra everything from nearly every pop artist everywhere. I think the British divisions had finally synthesized into a catch-all aesthetic. In fact, it was this extra-ness that we now think of in America when we think of 1980s pop music.

Back cover from Arcadia's So Red The Rose (1985)

But please—don’t call it New Romantic. It just isn’t cool.

-

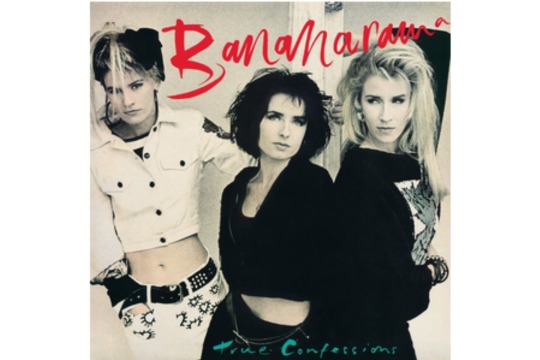

There were so many styles that emerged in the 80s from the streets, but none better than Bananarama, who were never hard to understand, being appropriated from street culture in England. Like the Go-Gos, when you saw them, it was pretty clear what they were doing stylistically, and it was never anachronistic. US or UK, you just got it.

Researching this entry, and looking around on the internet, I became interested in the word “naff”, which because it is British has had many permutations, but mostly means awful, ugly, no-good. I texted my friend British Rachel for the definition:

Me: Define “naff”

Her: Deely Boppers and Ra Ra skirts.

That was the 80s here. Nightmare.

Thank god for Bananarama!

On an internet message board from The Guardian, I found a more complete, and complex, definition:

Naff is polari (or palare), the gay urban secret language developed in London to ensure conversational privacy in public when talking about gay sex or insulting straight people. Polari was widespread in London, and particularly in the theatre, from the 1940s-1960s, suffered a decline in the 1970s and 1980s, and has had a revival since the 1990s. It consists of snippets of Italian, Latin, Spanish, Yiddish, Cockney Rhyming Slang, Black-slang and acronyms. Naff is an example of the latter - Normal As Fuck - and means drab, unfashionable, dull. By extension, it is a defining characteristic of straight people, who lack the style and swagger of the urban homosexuals.

- Gerard Forde, London, UK

Well. Excluding Duran Duran, of course.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantasia.

“Magic” (1980)

Olivia Newton-John

MCA Records

(Written by John Farrar)

Highest U.S. Billboard Chart Position – No. 1

ONJ, queen of the echo, absolutely stole my heart the 4 weeks this was No. 1 on the top 40 charts for all of August, but I am sure it went on long after, because I vividly remember running home from 9th grade to wait by our giant television stereo console—6 feet long, in walnut—to hear it hauntingly waft over FM radio one more time and once again fuel my dreams. The strings, the guitars, the little bit of ELO-like synthetic thing happening with the voices behind her, and yes, an echo on her voice to make Phil Spector weep, it was and is one of the greatest singles ever. For certain it was one of the gayest.

The big push behind the Xanadu soundtrack was that one half of the LP was Olivia (and I know now her genius producer and songwriter John Farrar) and the other half a then riding-high ELO (Electric Light Orchestra). Now ELO will show up here again; in the mid-70s the band produced Beatle-esque pop songs I adored, but at this stage I felt the singles were starting to verge on bombast (“All Over The World”, “I’m Alive”, and “Xanadu”—which is possibly even more camp than the movie, and a famous flop—were the hit singles by ELO). I also felt that the gorgeous things on her side of the record were rather sneered at as Top 40 pap, even though if you were to turn on any 80s station today it would be clear that the lasting hit from the soundtrack is “Magic”, and that you would be very hard pressed to hear “All Over The World” ever in your life again. But no one is prepared to admit that, even though neither artists where ever considered cool, then or today.

The Pan Pacific Auditorium, built in L.A. in 1935 and used as an exterior for the motion picture Xanadu (1980).

I actually loved the movie, and ran home eagerly right after to make paintings inspired by the Los Angeles/Art Deco fantasia it presented, plus Olivia’s hair and clothes, which were peak that year. All of the songs on Side ONJ (the album, which I am looking at, actually says ELO side and ONJ side!) were the really dreamy ones, and included two underrated ballads, “Suddenly”, her duet with Cliff Richard (Billboard No. 20) and “Suspended in Time”, another pyramid of echo. But none of them could touch the hem of “Magic”, where the planets aligned so rare, and there were promises in the air, and she’d bring all your dreams alive…. for you.

Well, me. Especially me.

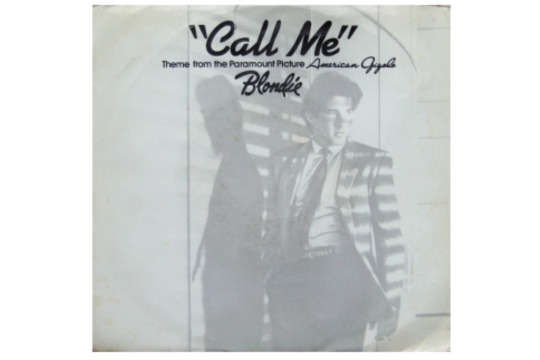

-

“Magic” 1980’s third biggest seller, was right behind Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick in The Wall” and behind the no. 1 of the year, Blondie’s “Call Me”, the theme song to the motion picture American Gigolo, starring Richard Gere, written by Giorgio Moroder with lyrics by Deborah Harry (based on her impressions of the movie). Gigolo, a film about a straight hustler in Armani clothes who works for a gay pimp, is one of the true style representations for the L.A. of 1979/80 (a feast for the eyes in terms of fashion and West Coast interior design), signaling both the extreme 70s feel of the movie, alongside the more Euro-centric eye toward the clothes and modernism that would define the first half of the 1980s that lie ahead. It would be a Los Angeles/Art Deco fantasia of a very different and darker attitude.

As a further aside, Gere’s hustler character in the film was named "Julian", which was soon to be borrowed for the drug dealing character Julian in Bret Easton Ellis’ classic dystopian novel Less Than Zero (1983), leading to a vision of L.A. even darker still.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Club

“Good Times” (1979)

Chic

Atlantic Records

(Written by Bernard Edwards and Nile Rodgers)

Highest U.S. Billboard Chart Position – No. 1

“The key of the success of Studio 54 is that it's a dictatorship at the door and a democracy on the dance floor.” - Andy Warhol

On April 26th, 1977, more than 4000 people showed up on 54th street between 7th and 8th Avenues in NYC to attend the opening of a newly revamped theater turned discotheque (once an opera house in the 1920s) for the grand opening of Studio 54. Eight thousand invites had been sent from many of the bests lists in the city; the line snaked around the block that night with people clamoring to get in. Many celebrities, officially invited, were unable to get through the soon-to-be famous doors. Disco, a popular fusion of soul and dance music, was on the ascendant: hedonistic, generic, joyful, color-blind, and sexually promiscuous (many of the song themes would be about copulation). It was in that year that two newly successful bandmembers from Chic named Bernard Edwards and Nile Rodgers were invited by Grace Jones and unceremoniously turned away at the door. Jones was never famously reliable; there is no telling where she was, but when they didn’t get in they went home and wrote an angry song called “Fuck You”, then changed it to “Freak Out”, then to “Le Freak”, which then went on to become one of the biggest disco songs ever written, and afterward they went to Studio 54 as often as they liked, because there is no golden ticket in the world like fame.

I am sure I don’t have to tell you what Studio 54 was: it was one of the most glamourous, glitziest, expensive spaces in New York. It was a party where everyone, anyone, had a good chance to get in. It held 2,500 and often had more; it had back rooms, was famous for the famous, and sex, and drugs. It had an incredible light show and sound system, and the best DJs. But most of all it was entirely and profoundly mixed: rich, working class, old, young, black, white, gay, straight, gender fluid, normcore. The two owners, Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager, had two rules: they wanted it full, and they wanted a mix, always a mix. Only the uber famous (Halston, Warhol, Jagger, Minnelli, Jackson) were guaranteed entrée; otherwise, it was the mix that mattered. The mix, the show (copious amounts of money on props and effects), and the music.

“A rumor has it that it's getting late

Time marches on, just can't wait…”

- Lyrics from “Good Times”

The club was the answer to a very gritty and tumultuous decade for the US and New York City in particular; it may be no accident that the theater once housed the old CBS studios known as Studio 52. In the 1950s and 1960s they filmed witty game shows here, which showcased intelligent repartee (To Tell The Truth, What’s My Line, Password, The 64,000 Question), shows that were representative of an urbane and prosperous city, and of high American culture. Rubell and Schrager kept a lot of the old leftover camera equipment from that era (whether as props or as a through-line it is hard to ascertain); in reopening its doors they presented a very new idea of glamor in New York, an antidote to the recent near-bankruptcy, inflation, gas shortages, and in 1978, a full-blown newspaper strike. Public housing in The Bronx was a disgrace (literally on fire in 1977 and broadcast live at a Yankees game by Howard Cosell), and fear and paranoia were rampant as Son of Sam ran around viciously killing young women. Out of all this chaos, Studio 54 and disco. Clearly people needed fantasy, and release, and from this scene arose Bernard Edwards (bass) and Nile Rodgers (guitar) of Chic, two highly accomplished black musicians.

The idea of the band was one of sophistication; the three male leads (which included drummer Tony Thompson) were accompanied by two female singers, and everyone dressed beautifully, almost in a retro vision of glamor; the songs were straight-to-the-dancefloor extended disco tracks, or lush ballads with strings. The songwriting was of exceptional high quality, and the playing incredibly expert (their first hits in 1977 were “Dance, Dance, Dance (Yowsah, Yowsah, Yowsah)” and “Everybody Dance”), and no one, no one, sounded even remotely like them: the guitar and bass lines were ingenious and infectious. In fact, if you want to time travel and exactly conjure the feeling of the late 70s, a Greatest Hits collection will take you right there. After “Le Freak” peaked in 1978 (it would be Atlantic’s, and parent company Warner Brothers, biggest seller of all time until Madonna’s “Vogue” in 1990) it seemed as if Chic, disco, and the nightlife of the Studio 54 crowd would go on forever. Except. Except. Was there something about the sound of Chic, a warped, dragging, rather sad tone, to their hits? The more they succeeded, the sadder around the edges the records became.

I never loved “Le Freak”, as good as it was. In 1979, I must have liked “Good Times”, because I bought it; it was the gray Atlantic label and a plain white sleeve, I remember quite clearly. I think I bought it because of the round piano swirl that opens the record— I was obsessed with how the song was constructed; it was perfect. But I also believe I wanted to understand how it worked, to get to the center of it, so I would drop it into the player and stare at it going around and around for clues that never came. Something about it made me sad. It would be decades before I went back to Chic and discovered the joy in that sadness; this was mature music for sophisticated people, and it captured those years so well, and with such elegance, and if it was sad, it was because there are always sad things seeping in, and possibly because their heyday, and all that high style, would be relatively short-lived considering the perfection of the records they were creating.

The Disco Sucks movement started on July 12th, 1979, in Chicago, Illinois. A radio shock jock held a record-burning stunt at a baseball game in Comisky park and 50,000 people showed up, and after the dj blew up piles of disco records, they swarmed the field and started a riot. Record companies began to re-label their sleeves as Dance Records, not Disco, and the white-wash officially began. The record burning has been likened to a Neo-Nazi event, largely inspired by disgruntled white rock fans, and inherently racially motivated, and I would say I fully believe that. It not without irony that the rather sad quality pushing against the melody of “Good Times” was realistic. It was to be their last No. 1 record under their band name, even if they would go on to produce 1980’s Diana (Diana Ross, but a full-blown Chic record, soup-to-nuts) which would sell 10 million copies, and both Edwards and Rogers would go on to have enormous careers as producers, especially Rodgers, with Bowie’s Let’s Dance right around the corner, not to mention Madonna’s Like a Virgin, produced by Rodgers (and on which all three Chic musicians play) as well as so many more. Nevertheless, I am ahead of myself. It is still 1979, and Studio 54 is still thriving.

“Now what you hear is not a test:

I’m rappin to the beat.”

- Lyrics from "Rapper's Delight” *

“Good Times” topped the Billboard Pop charts in August, 1979 (B Side: “A Warm Summer Night”). In September of the same year Nile Rodgers was in a club when he heard a song that clearly used the basic elements of their record: the bass, the guitar, a bit of the strings. It was “Rapper’s Delight”, a novelty record produced by a very savvy Sylvia Robinson to exploit the street scenes of break dancing and rapping in The Bronx, which were usually only performed live with a boombox. Certain songs could easy be rapped over, and “Good Times” was one of them. However, real rappers never considered recording. Enter Robinson, some fast thinking, and four quickly auditioned amateurs to make “Rapper’s Delight” as the Sugarhill Gang, and not only did she have it out in a flash, but on her own label, Sugarhill Records (Sugar Hill is a prosperous neighborhood in Harlem).

That night in the club, Nile Rodgers was not pleased. He and Edwards threatened to sue her immediately, and the matter was resolved quickly by Robinson giving them their writing credits, and thereby their money, and re-releasing it. What he could not have foreseen was that this novelty hit (it only went to No. 38 on the charts) would actually change music forever. It is the first successful mainstream rap record (we had the 12”, the first I ever had, in our house, and my brothers and sisters all learned the lines and became living room emcees), and it went on to establish Hip-hop as a genre. It would also lead to many copycats, and many interpolations of Rodger’s guitar and Edward’s tireless bassline, notably in Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust” and Blondie's “Rapture”.

Looking back on it, Niles feels very differently about one of the most famous examples of record sampling. "As innovative and important as ‘Good Times’ was,” Nile Rodgers has said, “ ‘Rapper's Delight’ was just as much, if not more so.” He is absolutely correct, of course. The success of the Sugarhill Gang led Sylvia Robinson, tireless entrepreneur, to convince a real rapper, Grandmaster Flash, to write and record a track about life as he saw it from the much grittier streets of The Bronx, and he released it as “The Message”, which was a pivotal first. Rap musicians reference this song endlessly as an inspiration, and I love it just as much for its contribution to electronic music.

Back in 1979 my 14-year-old-self stood for so long staring at my copy of “Good Times” as it revolved on the turntable. Was there a reason it felt warped and catatonic as I listened to it? I will never know. I wasn’t old enough to understand what the single portended, which was the future of pop music, years and years early. Things were beginning, and things were ending, right there, all at once, and right in front of my very eyes. It was easy enough to listen, but very difficult to fully comprehend. I needed another 40 years.

-

Sylvia Robinson, a veteran of the biz, not only produced Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five’s “The Message” but also sang on Mickey and Sylvia’s chestnut “Love is Strange” (1956) —think Dirty Dancing—as well as her own proto-disco song “Pillow Talk” (1973), predating the moans on Donna Summer’s “Love to Love You Baby” by years, and if you don’t know it (I needed some reminding) it has to be heard to be believed. Let’s just say it is at minimum one of the most suggestive Top 40 songs ever recorded. This was obviously a woman with the ears and ambition for a making a hit record. She is now known as “The Mother of Hip Hop”. She passed away in 2011.

Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager went to prison for millions of dollars in tax evasion in January 1980, but not before throwing a big party at 54. They served reduced sentences and eventually opened the nightclub Palladium. Rubell sadly passed away from AIDS in 1989. He was 45 years old.

*(Songwriters: Richey Edwards / Sherill Rodgers)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Studio

“Hey Nineteen” (1980)

Steely Dan

MCA Records

(Written by Walter Becker and Donald Fagen)

Highest U.S. Billboard Chart Position – No. 10

"From noon till six we'd play the tune over and over and over again, nailing each part. We'd go to dinner and come back and start recording. They made everybody play like their life depended on it. But they weren't gonna keep anything anyone else played that night, no matter how tight it was. All they were going for was the drum track.”

- Jeff Porcaro, Musician

Like a python wrapping itself around the beating heart of Rock and roll more and more tightly, this was the last charting single for the last album in Steely Dan’s classic period (it would be 20 years until they would release another album, Two Against Nature, in 2000). The stories of their recording methods reinforce this metaphor: what was once a real touring band of musicians had whittled itself down to just Becker and Fagen rehearsing the best artists in the world over and over and over again to achieve an exactness and fidelity that has never really been matched. I remember “Hey Nineteen” charting in 1980; it was right there on the radio beside Blondie’s “Call Me” and Olivia Newton-John’s “Magic”, playing nice but certainly not fitting in. They played it over and over again, a kind of spiritless meditation on something my teenage brain could never parse (The Cuervo Gold? The Fine Columbian?). Even today it is the kind of song one can never get to the center of, the smoothest track in the middle of the road: slick, perfect, and eternal. Like all of their hits it stuck around to sell a lot of copies but never really went to the top of the charts (one of the most successful bands ever to have never achieved a No. 1 anything).

Today some folks call this Yacht Rock (a term I mildly dislike as generic) which is ironic considering it is hard to imagine these two city slickers anywhere near a boat, or even in the wild. I can only ever see them in the studio playing mad scientist with the idea of fidelity. This much I know: I have a decent turntable setup and nothing touches Gaucho for sound quality—1979 is at the top of the top for the old idea of a great studio record. The only vinyl record that may top it is Fleetwood Mac’s Tusk or Dan’s own Gaucho. This is the result of all that squeezing: what starting out at a very high level with Can’t Buy a Thrill (their debut in 1972) only got more and more refined with every album. By the time one gets to Gaucho (after the lush but boozy hangover and strung-out feeling of Aja) there is a kind of plateau-ing, a linear quality, to all of the rehearsing and perfecting and playing every note until it almost fails to exist. Don’t get me wrong, this is a record I love—but at a distance, because it was constructed to keep you there.

There are so many legends surrounding the LP: that it was (up to that point) the most expensive ever made (over a million 1979 dollars); that it was heavily delayed by the band’s perfectionism (it took well over a year to record); that is was surrounded by tragedy and drug use (a terrible car accident for Becker, 6 months of hospitalization, his heroin addiction, and the death of his girlfriend). The hyper focus of Fagen and Becker, rehearsing musicians to exhaustion to get every note perfect, included their famous engineer Roger Nichols (formerly a nuclear physicist!) who was given $150,000 of the budget to create a computer that could process the live drum sounds for them to manipulate exactingly (he named it Wendel and the RIAA bestowed the machine its own framed, platinum copy of Gaucho in acknowledgement). There was the three-way legal battle between MCA, Warner Brothers and Steely Dan to actually release the thing (their original label, ABC Records, had been acquired by MCA). Lastly there was the sign of the times in the new “Premium Pricing” by MCA, a hike in album prices from $8.98 to $9.98 for the more expensively-produced records (I guess) which included Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers Hard Promises and the soundtrack for Xanadu, although I am not sure it ever went into effect after a lot of bad press. One legend that seems plainly true is that this year was one of the last for huge, expensive, lavishly-produced studio records. Like the old Hollywood system, it simply could not hold any more, and something leaner was right around the corner; if not inevitable, then necessary to move the art form forward.

Maybe this is the reason that “Hey Nineteen” sounded so anachronistic that year: it was by then a hologram from that ever-distant land of the 70s long player, richly produced, genre-defying, Empyrean, graceful. Go on to an internet message board or read any history of Steely Dan and you will find there the endless jabber about their relative goodness or badness in the great cause of Rock Music, by jazzing it up, or slimming it down, or mellowing it out, or squeezing it too hard in rehearsals (Gaucho is deliciously given one star by Dave Marsh in The Rolling Stone Record Guide, 1983) but trust me: pay them no mind. Just drop the needle, rejoice in the cleanest sound in stereo ever attempted by anyone anywhere, and spend time with some of the best musicians who have ever lived.

-

Roger Nichols, after being with the band as a peerless sound engineer for over 30 years (and on all of their 7 classic-period albums), was unceremoniously let go during the middle of recording of Everything Must Go, right after the disaster of 9-11. His wife Connie described it as an “emotional dagger to his heart and soul” and him as heartbroken. No definitive reason seems to be well known. Nichols sadly passed away in 2011 of pancreatic cancer at the age of 66.

Right before the pandemic Connie found a clear cassette in Nichols’ things marked “The Second Arr” in black Sharpie pen (she had never had the heart to throw away anything with his handwriting on it). This turned out to be a copy of a very famous lost master track from Gaucho, “The Second Arrangement”, which after months of recording and $80,000 invested, and complete, was accidentally taped over by a second engineer (whew - poor guy). This tape was from the night before that event. Fagen and Becker considered re-recording it, but being absolute perfectionists, they realized it was hopeless and moved on.

Connie Nichols waited out the pandemic to have the tape professionally converted, fearing it would fall apart. Later, another (even better) copy, a DAT tape, was discovered by her. It can be heard here (most clearly in the second post, clocking in at 5:46) from the substack Expanding Dan. It is rather wonderful.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Synthesizer

“I Can’t Go For That (No Can Do)” (1981)

Daryl Hall & John Oates

RCA Records

(Written by Sara Allen, Daryl Hall, John Oates)

Highest U.S. Billboard Chart Position – No. 1

Released in 1981 and hitting No. 1 at the beginning of 1982, one of the most forward-looking pop singles ever still retains a lot of its mystery. I have been all over the archives and it is impossible to locate the synthesizers on the song (especially the chimed ringing keyboard sounds that float over the top) but one of the definites is the deployment of an early, boxy, primitive drum machine called the Roland CompuRhythm CR-78. The apocryphal story is that Daryl Hall flipped the switch to the first setting, Rock 1, and immediately started to write the song. The band gathered around and quickly filled in the gaps, and the song was finished in a couple of hours. The lyrics center around the insane demands of their record company at the time, which Hall kept general so they could be reinterpreted, and because they were starting that wild ride of fame where material gets thinner because you are working all of the time, one uses what is closest to them, OR, because he was entering the Refusenik phase, where, as George Michael would evidence, one starts to complain about Uber fame, and say No Go.

This is the second post where upon close inspection it is the drum sound that signals the future. I had always enjoyed the perfection of the song as an example of synthesizers in the studio, but what I can understand now is that the song is really an example of more than a decade of fine tuning and distilling the many musical influences, especially Philly Soul, into this new poppier one. It may be no accident that this very same drum machine opens 1980’s “Kiss on My List”, which announced this new leaner sound for Daryl Hall and John Oates (their preferred band name), and the record they were recording, Private Eyes, was to shine this up to a high luster.

Nothing can truly unwrap the unique quality of “I Can’t Go”. It can’t have hurt that Sara Allen, Hall’s paramour, added her pop touches to the tune (she is an unsung and pivotal part of their pop success in the 80s as their co-songwriter), but what makes its special is the attack: spare to the bone, like the Roland drum machine that inspired it, everything pinned down to its meanest parts: drums, a lone guitar line, a sax solo, and Hall's (and Oates') super lean, dubbed vocals on top. Is it a new wave song, a pop song, or a soul song? It is hard to disassemble, but what is certain is that it hit No.1 on both the Billboard and the R&B charts, which certainly adds to their mystique and credibility. It is also on the record that while recording “We Are the World” Michael Jackson admitted to Hall that he cribbed the bassline for “Billie Jean” from the hit, by which Hall was amazed and flattered, never having noticed the similarities before. In this day some lawyer would sue for the fun of it, but it should be a rule that one good song should in part inspire many others, and that there is room for a lot of players at that table. For a song as good as this one, I doubt it could ever occur twice anyway.

“I Can’t Go For That (No Can Do)” hit the No. 1 spot for one lonely week at the end of January in 1982. By comparison “Ebony and Ivory” (a truly awful song) stayed on top for 2 months, and “Eye of The Tiger” for 6 weeks, proving the adage that only time will really tell you anything about anything.

Many bands utilized this early Roland drum machine, most notably its early use with the sped up (Bossa Nova?) noises that open Blondie’s“Heart of Glass” (1979) and it’s prominent presence on Phil Collin’s eternal hit “In The Air Tonight" (1981).

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The New Wave

“Rock with You” (1979)

Michael Jackson

Epic Records

(Written by Rod Temperton)

Highest U.S. Billboard Chart Position – No.1

Before I begin this entry a few disclaimers (in the style of the wonderful Andrew Hickey, creator of the absurdly great podcast The History of Rock and Roll in 500 Songs, which I wholeheartedly recommend), there has been so much press, and bad press, about Michael Jackson since his death that it should be acknowledged. Much of the bad news is the accusation that he was a constant, and serial, sexual abuser of young boys. The jury will forever be out on these accusations based solely on his influence and power, which have grown steadily since his death in in 2009. His estate is vastly wealthy, and continues to grow. It does not surprise me that he was disturbed considering the amount of child abuse he suffered, or that the truth was heavily twisted by him (just watching him in old footage deny his physical alterations, plain for the eyes to see, is evidence enough that he was severely distorted in his relationship to truthfulness). However, I cannot deny how powerful and productive his artistry was and is, and his influence is undeniable. His role as a conduit for other artists alone is wildly impressive. He was one of the greatest innovators in many ways. I believe he was in a lot of pain, and perhaps he caused a lot of pain by displacing that. But his musical influence, which is the reason for this entry, is my absolute focus.