#'meaningful to you' does not have to mean 'productive within a capitalist system'. The point is not 'every waking hour of every day

Text

I find it kind of silly that so many of those "time based life rule" sayings are like ~deep serious guidelines~ of some sort, but then there's that one other Well Known Rule that's just like "hrmm can I eat something off of the ground or not"

#the duality of human condition.. two biggest concerns in the modern era are attempts at self fulfilling productivity#and also 'if i drop my sandwich can i still eat it :('#Also while capitalism is often linked with/the source of hyper productivity culture - note that I do not mean the images in that context#'meaningful to you' does not have to mean 'productive within a capitalist system'. The point is not 'every waking hour of every day#must be spent in the most societally productive grinding mindset hyper efficency mode possible' but more like#if you've always wanted to learn french ever since you were a kid and you think it would be fulfilling to you (just because you like it#absent of any larger purpose like using it for a job/monetizing it somehow/etc.). and you've just spent like 5 hours straight on tiktok#or something mindlessly scrolling the internet. maybe someimtes it'd help for your own personal fulfillment in the long#run to try to - the next time you have 5 spare hours - work on learning french or something that is actually significant to you#as a person and that you'll be glad you worked towards. instead of weeks and weeks passing by and feeling you have nothing to show for it#or etc. AAANYWAY. The images/rules themselves are also NOT the main point of this post. More just the juxtaposition of them together#and the fact that 3 of them are serious seeming while one is so mundane it seems silly in comparison.#BUT even though they're not the main point . I still didn't want it to come across as if I was like promoting or buying into capitalist#productivity culture propaganda or etc. I don't find productivity tips like this inherently bad as long as they're kind of divorced from#those ideas. I think it's still important in life to have goals even if those goals exist outside of the typical expected framework.#I mean that's actually part of why a culture of chronically exhausted overworked deprived people is damaging because if you#'re forced to spend 85% of your waking time working at some job that is perosnally meaningless to you that brings you nothing that#youre only doing under threat of starvation and houselesness and etc. then of course you don't have much time for hobbies or things you car#about and of course you'll feel more aimless and personally unsatisfied and like life is not fulfilling or interesting.#Productivity and efficiency is GOOD actually. as long as it's able to be directed in ways that are actually meaingful to the community or#individual and bring some sort of feeling of fulfillment or progress or accomplishment and working towards a person's personal ideas#of happiness whatever those are. rather than just working away aimlessly so some guy you don't know can buy a 20th house or etc. etc.#ANYWAY.. lol.. Me overthinking things perhaps.. probably not as likely#that people see the silly little cat images and go 'WOW EVIL you must be a capitalist grind culture lover' like its pretty clear#thats not the point... but... just in case... lol.. I loooove to over clarify things that don't actually need clarification

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Memes Kill Creativity?

Memes vs. Genes

In the 1976 book The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins coined the term 'meme' to describe something with symbolic meaning that spreads by imitation from person to person within a culture. This idea is an analogue to the nature of selfish gene, described similarly as a piece of genetic material possessing information required to be able to replicate themselves inside a living. The only key difference in both terms is that the gene is natural, while memes are artificial. The rest of memes' operating schemes completely mimic the genes perfectly. In our current timeline, memes as we know today are taking many forms: as image macros, short videos, and rick-rollicking music. Memes in imageboards and forums have been pushing internet porn traffic into a stalemate and putting our power grid into unnecessary burden. Of course, memes are not to be regretted, but otherwise need to be taken seriously, since they are able to put our current understanding of media industry and economic system into shame.

As with every other thing that have existed, memes are not exempt in its dualistic nature. If you ever venture to the depths of dark web, you may know that memes also took part in the infamous mimetic Tumblr-4chan War. Not only that, some memes are reportedly causing harm towards some users, even though it is often disguised or said to be a dank joke or mere sarcasm. Memes have seen its share of use in online bullying, mass shootings, and hate crimes, cowering behind the freedom of expression tag. Regardless, memes are also an extremely effective form of information transmission. Like all living systems with no set moral standards, memes do evolve and are subject to natural selection. Memes, like genes, actually work like a mindless machine. Again, this is eerily like the performance of DNA in living systems. The last thing we want from this thing is virulence.

Every day, something went viral on Twitter. Hashtags are flaring into the top trends, some videos are being watched billions of times, and another cat vs. cucumber pic garnered thousands of likes. Viral properties of a virus (duh) is defined as the capability to multiply quickly in relatively short amount of time. The term saw a huge increase in usage during the dawn of the internet age and the rise of computer malwares spread through unsecured ports of network protocol. This term is being applied to memes, as it is like a virus (which is a pure embodiment of a selfish gene). Now, a lot of people are utilizing memes to create art, because it enables them to cater the short-attention spans of current internet users. They create shorts, illustrations, inside jokes, and small comic strips. Some of you might not agree with me on this one, but stay with me now and I will explain to you why I would like to treat memes and art as a single unit of interest in this argument.

The dawn of meme-technology

Viral memes and their popularity are now often considered important in defining a time period in the internet culture. Now every netizen can somewhat distinguish the approximate age, sex, and political views of other users from the usage of rage comics, meme songs, and meme platforms they use. Intuitively we can make a generalized difference between the userbase of Reddit, 4chan, 9gag, Vine, and now Tiktok. Others, by the share of relatability with sub-genres of different areas of interest (film memes and game memes). Some others, even, in the perspectives of different social and economic class system (first world problems and third world success memes). Meme preferences to us netizens are ironically giving away our anonymous identity. Identity which the media companies are vying to get their hands on. That's where I would like to come into my opening argument: both memes and genes which originally possesses no intrinsic value, suddenly become a subject of value with technology.

How do we draw the logic, I say? The ones and zeros inside electrical systems are value-free, so does DNA in living cells. As we meddle ourselves with biotechnology to manipulate genetic material for profit, we also simmer ourselves in the computer sciences and tweak physical computation to perform better. We give value in the inanimate object by manipulating them. In our world, we often heard these expressions: that communication is key, sometimes silence is golden, and those who control the information wields the power. What’s these three statements have in common? Yes, information and expression. Memes are the simplest form of both. This is the beginning of the logic: memes are no longer in and on itself independent of external values. The infusion of utilitarian properties in memes as artificial constructs are seemingly inevitable, and for the better or worse shapes our current society.

We might have heard that somewhere somehow, the so called ‘global elites’ with their power and wealth are constantly controlling biotech research and information technology—or, in the contrary, they control these knowledge and resources to keep shovelling money and consolidate their power. Memes are one of their tools to ‘steer’ the world according to their 'progressive agenda', seemingly driving the world ‘forward’ towards innovation and openness. Nah, I am just joking. But, stay with me now. It is actually not them (the so-called global elites) who you should be worried about. It is us—you and I, ourselves—and our own way of unwittingly enjoying memes that are both toxic and fuelling the age-old capitalism. Funny, isn't it? We blame society, but we are society. But how are be becoming the culprits yet also be the prey at the same time?

Middle-class artists are hurt

Now, aggressive marketing tactics using memes are soaring. Media companies are no doubt cashing in the internet and viral memes to their own benefit. Streaming and cataloguing are putting up a good fight compared to their retail, classic ways of content delivery. This is quite true with the strategies of Spotify and YouTube, other media companies alike. They can secure rights to provide high-quality content from big time artists and filmmakers and target these works directly to the end consumer, effectively cutting the cost of distribution which usually goes to the several layers of distribution line like vinyl products, radio contracts, and Blu-ray DVDs. I believe this is good, since it is like an affirmative action for amateur artists to start a career in the art industry. Or is it? Does it really encourage small-time artists to begin? Yes. How about the middle-class artists? Not necessarily.

You might sometimes wonder, “how the hell did I get somewhere just by following the trending or hot section in the feed?”. This toxicity of memes often brings some bad things to our tables. Social media algorithms handle contents (like viral memes) by putting those with high views or likes to the front page, effectively ‘promoting’ the already popular post and creating a positive feedback cycle. By doing so, they could capitalize on ad profits on just few ‘quality’ contents over huge amounts of audience in a very short amount of time. The problem is most of the time, these ‘quality’ contents have no quality at all. They just happen to possess the correct formula to be viral, with the correct SEO keywords and click-bait titles with no real leverage in the art movement. This way, I often find both the talented and the lucky—of which the boundaries between them are always blurred—overshadow the aspiring ‘middle-class’ artists who work hard to perfect their craft.

If you are already a famous guitarist with large fanbase, lucky you, you are almost guaranteed to top the billboards. What, you have no skills? Post a video of you playing ‘air guitar’ and… affirmative actions to the rescue. Keep on riding the hype wave and suddenly you get to top trending with minimal effort, thanks to your weird haircut. Those haters will surely make a meme out of your silly haircut, not even your non-existent guitar skills. But still, hype is still a hype, and there’s no such thing as a bad publication. This also answers why simple account who reposts other people’s content could get much more followers than the hard-working creators. Not only being outperformed by the already famous artists taking social media by storm, now the ‘middle-class’ artists are also dealing with widespread content theft and repost accounts because of the unfair, bot grading system. It is unimaginable how many nobodies got the spotlight they don’t deserve just because they look or act stupid and the whole internet cheers around them. Remember, this is not always about the artist, but also the quality of the art itself. I believe a good art should be meaningful to the beholder.

Why capitalism kills creativity

The problem in current art industry is that we are feeling exhausted with the same, generic, and recycled stuff. We indeed already see there’s less discourse about art now. Sure, the problem lies not in the artist or medium, but is in the viewers—the consumer of the art form—and how the capitalist system reacts to it. The hyper efficient capitalist system doesn’t want to waste any more time and money trying to figure out what’s new or what’s next for you. What we love to see, what is familiar to us, the market delivers them. The rise of viral memes phenomenon in the social media pushes the market system to the point where they demand artists to create the same, redundant, easy art form. Listen to some of The Chainsmokers’ work and we'll see what music have become: the identical 4-chord progression, the same drop, the predictable riser, and the absence of meaningful lyrics. We sat down and watch over the same superhero movies trying hard to be the next Marvel blockbuster. The production companies are also happy not to pay writers extra to come up with new ideas and instead settle with borrowed old scripts from decades old TV drama. Disney's The Lion King and its heavy use of the earlier Japanese Kimba The White Lion storyline is one guilty example.

Despite it initially being an economic system and not a political ideology, it is untrue that many Marxist philosophers usher the suppression of art. While it is ironic that Stalinist policy intends to curb ‘counter-revolutionaries’—in this case his enemies—by limiting freedom of press and media; American propaganda added further so that it seems that the ideology is also limiting art and kill creativity. We all know the Red Scare in the U.S. during the Cold War saw a popular narrative of communism and socialism that is devoid of freedom of expression. This state propaganda then further become ‘dehumanization’ and make freedom of expression invalid under the guise of equality. Marx argue that total equality is not possible, and the uniqueness is being celebrated by having them doing what they do best and provide the best for their community. Thus, an individual's interests should be indistinguishable from the society's interest. Freedom is granted when the whole society is likely to benefit from an action. According to Mao in his Little Red Book, freedom of expression in art and literature, after all, is what initially drive the class consciousness. It is capitalism, not communism, that kills creativity.

If left unchecked, the threat of this feedback loop is going to cause a lack of diversity, resulting in stale content, less art critique, and overall decline in our artistic senses. Artists’ creativity that are supposedly protected by the free internet are destroyed within itself through the sheer overuse of viral memes. Capitalism has successfully turned the supposedly open, free-for-all, value-free platform that is the internet against the people into a media in which they are undeniably shaping new values on its own: the art culture that's not geared towards aesthetics and appreciation, but towards more views and personalized clicks. How social media and media industry caters to the demands of the consumer are, in Marx's own words, “digging its own grave”.

Spare nothing, not even the nostalgia

Well, people romanticize the oldies. The good old days, when everything is seen as better and easier. Look at the new art installations that uses the aesthetics of naughty 90s graphic design to become new, the posters released in this decade but with an art deco of the egregious 80s pop artist Andy Warhol, or the special agent-spy movies set frozen in the Nifty Fifties. Nostalgia offers us a way to escape from the hectic choices of our contemporary: different genres of music, dozens of movies to watch, and different fashion to consider. We choose to settle with our old habits, that we know just works. Remember how do we throw our money on sequels and reboots and remakes of old movies we used to watch during our younger days? We don’t even care about new releases at the cinema! Did you remember how Transformers 2 and their subsequent sequels perform at the box office at their opening week?

The huge sales of figurines and toys of Star Wars franchise—if we could scrutinize them enough—came from the old loyal fanbase of the late Lucasfilm series, not primarily from new viewers. Then suddenly, surprise-surprise. Our love for an old franchise deemed dead enough to be remembered and treasure soon must be destroyed to pave way for three new outrageous sequels (the ones with Kylo Ren and Snoke) by the grace of our beloved capitalism. Sadly, nothing is left untouched by the capitalism’s unforgiving corruption. Nostalgia has become a gimmick that makes people like some art more than they should, because it’s familiar. It is another way of squeezing your pocket dry.

Not that it is bad to make derivatives like covers or remixes, but the trade-offs are far too high. Consequentially, the number of original arts is now very little, because artists don’t bother making new stuff if they just aim for a quick buck. Most of the young adult novels are essentially the same lazy story progression with only different time setting and different character names. Most of them even have the same ending! No more a beautiful journey like the thrillers of Dan Brown or the epic adventures of Tolkien’s Lord of The Rings, which defines their respective times. Do we seriously want to consider Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey as a unique work? Isn’t the Hunger Games and the Maze Runner essentially the same?

If you play video games, you must have known that the trend always starts over. Game developers are making gazillions of sequels, and only a few of them that are actually good. Most are outright trash. Oh, wait, old video games like Homeworld are also getting remasters to cater the demand of nostalgic consumers. No new Command and Conquer release from EA Games? Re-release the 25 years old Red Alert because people will re-buy it! Profit!

15 June 2020

8.03 PM

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

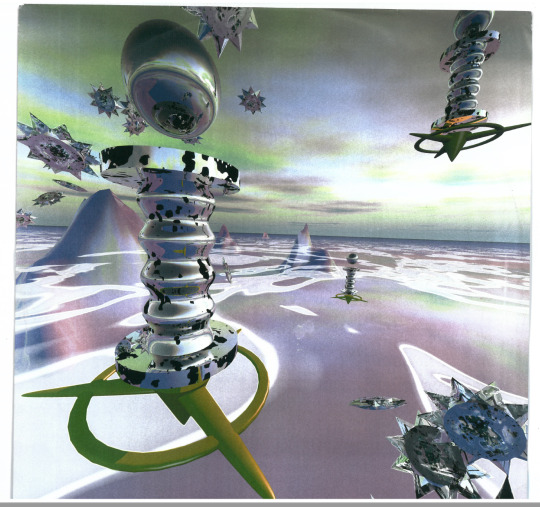

As a label we have made efforts to properly engage in marketing bureaucracy and online visibility tactics that are required if you wish to engage certain audiences with your brand (especially younger internet-integrated generations). However, for creative satisfaction, and as experimental speculation with these micro-capitalist tendencies, as a transmitter of audio/visual media, we confront the orthodox of music marketing and media consumption by subverting these conventions in through poster design and music branding. We have continuously worked very closely with Gabriel Thomas, a visual graphics designer and 3D animator who has been instrumental in developing the accompanying visual language to our sound work. With 3D clay simulation software, we have designed typography and graphics that presents our collective warped vision of futurism and accelerated rave culture.

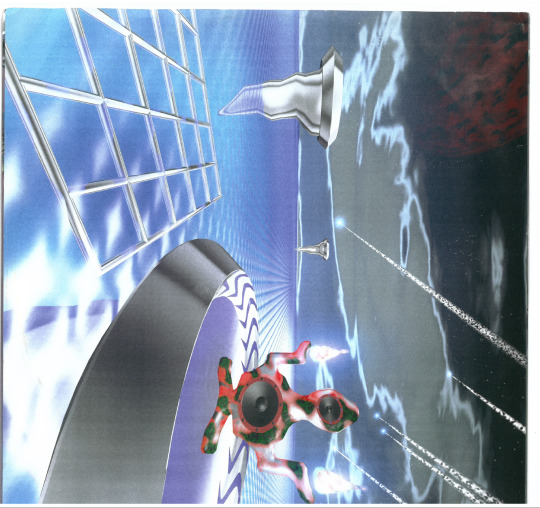

We take inspiration from the radical science fictional and virtual visual styles of techno EDM music that has evolved through the 20th and 21st centuries. Below are some scans from a book titled Techno Style: The Album Cover Art, put together by Martin Pesch in 2003:

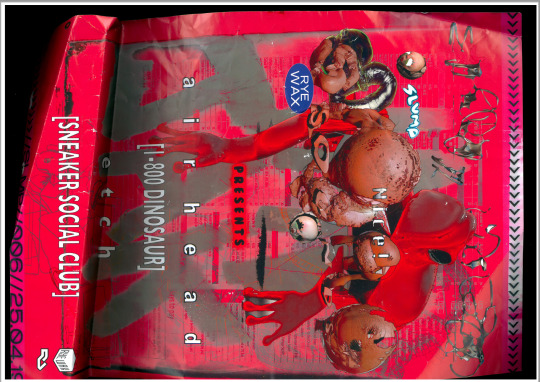

Below this is the artwork for DJ Haus’ Artifical Intelligence EP on Rinse:

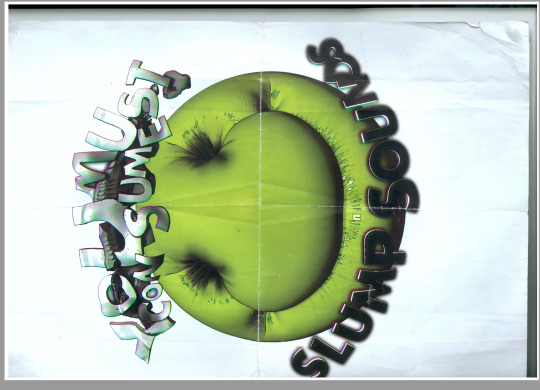

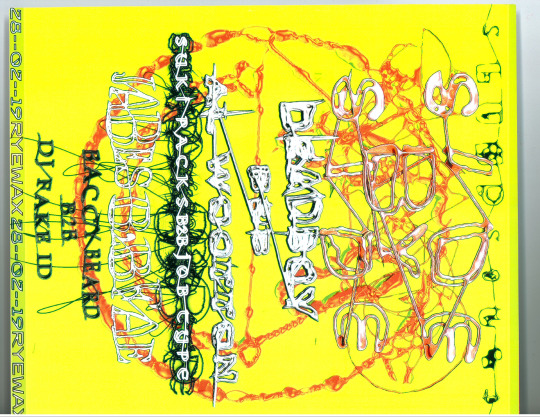

Below are various Slump Sounds visual materials, flyer posters and visual branding eperiements:

^The above typographical experiments quite literally embody a visual comment market capitalist consumerist branding, by integrating the words ‘YOU MUST CONSUME’ backwards within the name ‘SLUMP SOUNDS’.

To this end, we started plans for a website (shown below), and with Gabriel’s experience in web design assistance, have put together a conceptual mock-up that successfully incorporates the virtual potential of digital software and immersive screen art with DIY cyber-punk imagery. The visual concept is to can be accessed here: https://elated-shirley-a5af24.netlify.com/

These are collaborative efforts that involve a dialogue with Gabriel and direction from me and Al on the visual concepts behind the website, and though i consider this project a successful ongoing collaboration that will form a major part of my sonic practice, and that of the future of Slump Sounds, I am personally relatively unexperienced with design software and coding. Therefore I wanted to explore an alternative avenue of creativity, with the intention of a decidedly lower-fidelity visual language as a possibility for my final graduation exhibition in April. I have been drawn towards physical and more laborious methodologies of visual and sonic art, such as collage, printing, zine-making and sound production using analog hardware, without the need of a laptop. This sensibility can be seen in the virtualisation of non-virtual things such as graffiti or a marsh.

The search for meaningful and creatively satisfying sound work has led me to the world of analog art and audio programming with physical machines and tactile buttons and nobs. Admittedly, I’ve been very slow to embrace the potential of analog gear for a long time. I believe this has something to do with a sense of not believing myself to be as scientifically inclined as I felt was needed, or feeling the need to learn more about the engineering and mathematics of synthesis or sequencing. In hindsight, this is an unproductive outlook, especially considering the lineage of radical electronic artworks that were born from mistakes or glitches in systems of sound creation and reproduction that characterises a cyberpunk reading of experimental music.

This desire intensified through a process of familiarising myself with pre-digital sound gear; what began as the need to hear cassettes and not owning a cassette deck, which forced me to choose one, locate it, buy it, and figure out how to get it to play what I wanted to hear, which then turned into vinyl and a mixer, and then cheap and simple drum machines. It still remains a part of my practice that I believe requires much more actual play and practice time... Still I contemplate the elusive nature of analog signal processing as when I first played a Casio electric keyboard at a young age. It is important to point out, however, that this does not thus lend me a masterful understanding of digital media processing either, only an ability to abuse to it to my own indulgent ends. Any effort to demystify this practice is a step in a right direction.

Since my introduction to the keyboard, I can say for certain that my interest in electronic sound production and the history over human-machine interaction that defines parts contemporary society and techno-futurism has become a creative obsession. To live and work with meaningful creative disposition within the modernity of media noise and cultural saturation, and having been introduced to the infinite-possibility blank canvases of digital audio work stations at an early age, where my lateral creative mind quickly fostered an addiction to the stress of sonic novelty, erratic compositions that quickly deconstructed or changed an idea or process without allowing time for deep listening or trance-inducing sonic immersion, it has become impertinent for me to seek more visceral, authentic and tactile methodologies. Efforts to correct this habit of laptop art-making are a defining feature of my current personal interests, and my efforts to engage in a more authentically rooted and personal relationship to my sonic practice, extending beyond music and sound production into physical and visual art practices that steer clear from the transience of digital media online allow me to distance myself when I want to from digital work. My peers and I working within Slump Sounds are slowly making progress with collaborative analogue hardware production systems and studio building. Money and time are major factors in this process, though, as Simon Reynolds explains in his lecture on DIY, in some ways the romanticism of investing resources into more meaningful outcomes more appropriately reflects ‘a convergence of energies and passions‘.

On the rare occasion I can return to Leeds during term time for longer than a day, I take the oppurtunity to connect with the label crew to work on the upcoming releases and discuss label business. Al owns a Roland SP808, an Arturia Microbrute and some decent speakers. I brought along my Korg Volca Beats, a reverb pedal and a folder of samples and noises from my own work and sampled from floppy disks and youtube videos. The attached Soundcloud file at the beginning of this post contains the resulting noises we made over about an hour of twiddling and listening. To me the sounds are an evocation of our collective interelations with Grime, Electro and DIY electronics. At the time we discussed as much as we could about the potential of performing with such a setup, and how possible it would be to get a project like that underway, with a focus on the ‘total package’ concept of physical releases, sleeve inserts, flyer promotion etc. that was conceptually a step back from the hyper aesthetics and digital marketting of Slump Sounds. We shared our fascinations with symbolism and aesthetic reflections of experimental arts cultures and avant-garde modes of living, carried through subversive strategies of music branding with the politics of contemporary DIY culture and cyberpunk. In an age characterised by rampant commercialism and media saturation, to what end can alternative practices provide meaning or transcendence from societal norms? Our decision was to begin developing a more DIY post-punk inspired subgroup uber the banner of Slump Sounds, where we could experiment with tactile art-making and more ambitiously conceptual projects not necessarily intended for club systems or commercial profit - enter, LosBundazGanks.

During this session, I talked with Al about my visual investigations into truth, hyperreality and simulation for my Major Research Project, and we decided to begin working on and combining the sounds we were producing with the visuals I have been collecting and researching. Of the 300 hundred or so images that we curated, all of them relate in some form to the idea of simulation and reproduction. The examples below consist of digital cuttings from an online version of the Official Gazette of the United States Patent and Trademark Office: Trademarks, which were selected on the conditions of their visual or conceptual affiliation with the idea of simulation, truth or audio/visual fiction. My intrigue in the catalogue, which gives a written description of each logo, was in the symbiotic relationship between the written definitions and meanings of the symbols, which in turn represented aspects of market capitalism and commodification. These first drafts were then processed through effects on an old version of Microsoft Word. The ‘edges’ function can, with experimentation, produce a digitally rendered appearance of stamping or screenprinting, much like the DIY Zine making methods of hardcore music and art communities:

After this, we highlights the inherent entanglements of audsio/visual simulation and truth by juxtaposing these images with other found visual materials. The intention was to build moodboard for reference in the future when we will have the time and resources to develop the idea of a Los Bundaz Ganks physical release or performance.

This process has completely shaped my outlook for future projects, and I have decided to introduce a significant portion of this research into the ideas for the graduate exhibition in April. For an effective audio installation or performance, I consider it important to side-step the context of a gallery situation, which too often in my experience has provided little to no communication in some form other than the actual pieces/sculptures/sounds of the conceptual analogies or research methods that brought the artist to design/build/draw attention to in the first place.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

here’s a fun fact i haven’t shared that’s been going on for a LONG time: at my work, for our logins, we have to change our alphanumeric passwords every quarter. after my first password, which i wasn’t thinking about beforehand so just used an old reliable of mine, i thought “hmm, well, this will be easier to remember if i have a system. hey...17 has thirteen members, and i know their age order, bc that’s how i learned their names to begin with. i can start with one based on seungcheol and go down the line, and if i get all the way to chan, well, i’ll know i’ve been at this job too fucking long.”

welp. i’m on minghao now.

however, with the way life is going, it’s looking like seungkwan’s gonna be my last Password Boy...bc YA BOI IS MOVING TO ATLANTA

probably. most likely. by early summer.

it occurs to me that while i often share anecdotes of the past, i don’t make many posts about my current circumstances. considering this is a new account, with far fewer followers and mostly mutuals, i think i’ll be making more blog-style posts here now.

for those who are newer or just haven’t seen me mention it, i’m currently a scribe, a transcriptionist/editor, working out of an almost call-center-like office in a florida college town. thankfully, having also done call center tech support work, the difference is we just process recordings. (dealing with tech support was so stressful, i got fucking scabies at 23 and missed a month of work, but that’s a story for another day). being a scribe is a phenomenally boring and isolating job, for the most part, and one i am very good at. it’s a very safe job for me, in a lot of ways. it sucks and i hate it, as one can find with basically all scribes throughout history, but it also takes a very particular set of skillsets, ones i happen to have, that make it easy as fuck. there’s good and bad. i set my own hours, within reason. there’s very little management meddling as long as i don’t fuck up. i can easily be a bit late and never have anyone talk to me about it as long as i get my hours done. however, it’s physically painful to sit and type for hours and hours, and psychically damaging, i’m sure, to spend hours a day wishing i was doing something else, to be paid a pittance (but it’s still above minimum wage so i guess i should be grateful?) as a skilled and experienced laborer to type all day about other people’s money, regularly including people who make as much in a month as i do in a year. on the other hand, my gods are some of the oldest and coolest (my favorites are seshat and nabu), and at this point, after almost 4,000 hours of doing this, i’d have to actively work to get fired. it’s safe. there’s no opportunity for advancement, there’s no sense of my time meaning something in the grand scheme of things, there is no meaning at all. i am grease in the wheels of capitalism. it robs me of the energy and prime writing hours to use my hands to put down my own words, not someone else’s. but it’s safe.

my apartment’s getting sold out from under me in a few months, and i was initially panicking, thinking about how i could find new roommates, where i could live that would be easily accessible to my work without a car, even looking up info about the apartment complex next door to it - which, between work, home, and publix, would limit most my external world to about a square mile.

then i was at work earlier this week and realized...why am i having so much anxiety about being able to keep a job i fucking hate?

change is terrifying to me. it’s part of my coping mechanisms with my untreated adhd, i’ve come to realize (with the help of friends who have diagnosed adult adhd and are like no, yeah, you absolutely have it). i have to keep a very regimented rhythm of life just to function at all, which took me way too far into my 20s to even figure out. i need to wake up around the same time every day, get dressed to leave at the same time every day, make sure my wallet is in the outside pocket of my bag, my key is in the front pocket, i’ve got my publix bag rolled up in my purse (and now that it’s winter a hat and gloves just in case), and my umbrella (also just in case), and my tablet that was a gift from my beau (loaded up with pages to read offline while waiting for and on the bus), and a paper book or two (in case for some reason i can’t read on the tablet), and a snack for mid-shift so my stomach won’t spend all day hating me. all of this i verify both before i leave my room and before i close the locked front door behind me, especially the wallet and key.

if this sounds dreadfully mundane, please understand, i had to learn to make this a regimented routine, every step of which i need to consciously account for even while half asleep, or else i will forget something. more than once this compulsive checking to make sure i have my wallet and my key a second time before locking the door has saved my entire day. all that before even leaving the house. i had to learn this on my own to quiet the constant racing anxiety that put me in the ER a couple years ago with an inability to even keep down food because i had no idea how to be a functioning independent person. and so much of that is mentally tied to this apartment, to this job, bc at 26 years old a couple years ago, after over a decade of battling depression and adhd and finally getting treatment for the first, at least, i was finally equipped to and also forced to become an independent human being in a capitalist society. and it was terrifying. but routine is safe, now. i do the same thing every day during the week, at the same times of day, and sleep in a bit on weekends and do nothing. time passes and passes. i invent games and new routines for the day, meaningful boxes to tick, just to establish meaning back into my life.

i’m getting too far off track. sorry, it’s the adhd.

the point is, change is terrifying. but my beau - sorry for the awkward term, but “beau” and “sweetheart” fit us better than bf and gf, especially considering gender and long-distance stuff - told me as soon as i told him the news about the apartment that i could always come to live with him. i dismissed it as last resort at first. like, we’ve known each other for almost 10 years, more couple-y than ever the last two, and he visits me when he can. we’ve never lived in the same city, but in a sense, we both were there to watch each other grew up, despite that we first started talking as friends when i was probably 19 or 20 and he was 31. now i’m 28 and he’s 40. he’s inspirational to me, because for a long time, he was living the kind of life i am now - working bullshit jobs that don’t mean anything, working and living to survive, scrounging meaning and joy in independent scholarship and pop culture. but somewhere in his mid-30s, he changed the whole direction of his life to throw himself into a career in film production. it takes an extraordinary amount of self-motivation, courage, fearlessness, energy, time, EVERYTHING to live the kind of life he does, living the freelance life, going from shoot to shoot all across the southeast, constantly on the hussle. but he has a career. he’s doing something amazing that he’s good at and he loves, and bc he’s about the most likable guy alive, he has contacts everywhere, through all levels of the industry. and he’s just about the most capable person i know.

so when i had my realization, why am i so worried about keeping this job i hate, i realized swiftly on its heels that i was just terrified of change. i wanted to keep things safe, even if it was a marginal existence - still, a safe one. but change can also bring opportunity. moving in with him wouldn’t just be an act of charity on his part, but helping the person he loves to make a meaningful change forward in life. Atlanta is the capitol of the South. i could get a job in publishing in atlanta. i could get a job in the film industry in atlanta (fun fact: georgia is now the center of film production on the east coast. he knows a ton of people that worked on stranger things!). i could write for a living in atlanta. i could be a script doctor like Carrie Fisher, i could edit for a living for more than some finance office’s memoranda ephemera, i could have a life where i was able to create, and not just in my spare time and for fun. i could live in atlanta, and not just survive. my beau, as mentioned, has contacts everywhere, and has already hooked me up with a couple writer-type-creators in the industry to mentor me. i can do it. i will do it. even my mom said i’ll do better there than in the waypoint city i’m in now (and also helpfully reminded me she rents uhauls now as part of her own self-owned business).

tl;dr either in april or june, depending on what i can convince my current fairly indulgent landlord on, i’ll be moving to Atlanta and starting a whole new life. my beau has a two-bedroom (thank god, bc if i’ve learned anything from long-term moved-in relationships is that i need my space, and he also agrees on that on his end) and his place is less than a mile away from a publix and also a main bus line and a MARTA station, so i could be easily independent as a non-driver (important not just from a relationship standpoint, but also bc realistically he’s only home about a week out of a month, cumulatively). also, he has a cat! a tabby boy named dalek! bc he’s a fucking nerd!

#t#don't reblog /#i figure i'll have to get resigned to the whole boyfriend/girlfriend thing as introduced to others#i don't super mind it it just doesn't feel...accurate#but if it's necessary to avoid awkward conversations and lend legitimacy in shorthand to how much we very much do love each other#then sure#long post

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm technically new to all this political stuff, so I hope you can help me out! - How would you briefly explain to someone why capitalism is bad? Why is the US also bad, and how would you respond to someone who claims that it is a "free country" and that we "at least have the freedom of speech and the freedom to protest", etc. I'm very bad with words, I'm just a dumb kid. Sorry for bothering, and thank you. (:

I will answer these questions, but first off, I would say - read, listen, think. Ultimately it’s better if you can develop your own conclusions through a mutual dialogue and learning process with others rather than getting your talking points entirely from others, especially on a social media platform. But if you want resources or recommendations from others, Tumblr can be useful, and I’m happy to provide if you want.

As for answering your questions, it really depends: who is the person you’re talking to, and what do you want out of the conversation? Not everybody has the same interests or concerns or values, and sometimes they’re intractable for whatever reason. So there are other factors that should be taken into account. If you’re just trying to “win” a discussion, I don’t personally think that’s a worthwhile use of time - but if you are trying to convince someone interpersonally or just get better at clarifying your own perspective for the future, that could be valuable.

So, answering your questions under the cut:

How would you briefly explain to someone why capitalism is bad?

A) Capitalism stifles human freedom, and does so in both passive and active forms. This seems counterintuitive because capitalism is peddled as the fulfillment of human freedom (by way of innovation and freedom of choice - Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman have claimed that so-called “economic freedom” is a necessary condition for political freedoms), so bear with me.

Passive forms: In order to live under capitalism, most people have to work - and for that matter, they have to tailor skills and interests to be rewarded on the labor-market. Furthermore, since capitalism is predicated on the principle of private property, some kind of state is necessary to enforce that principle through the law, and the state and law are blatantly forms of social control (see David Harvey’s A Brief History of Neoliberalism for more info on this). As a Christian myself, this is the essence of idolatry. The capitalist world-system was made by humans, ostensibly to serve human needs, but is both bad at serving those needs in many ways (for reasons to be explained below) and uses us as the fodder for its self-perpetuation!

And this generates alienation. There is nothing necessarily “wrong” with depending on other people - humans are social creatures and are themselves influenced by the conditions under which they live no matter what those conditions are. But when your labor and the product of your labor benefits others far better than it sustains you, when you are pushed to view all other people as competitors, when you are subjected to various forms of interpersonal and structural domination (detailed below), this produces quite a bit of psychological distress. (Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism and Deleuze & Guattari’s Capitalism and Schizophrenia touch on these in different ways.)

Active forms: Historically, in order to get people to be wage laborers, they had to be forced to do so - in England, which is generally regarded as the birthplace of capitalist modernity, laws were established to oblige people to work for a certain period and punish them if they didn’t. Similar legislation cropped up in Germany and France. And, of course, there was also the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the abuse and exploitation of indigenous populations throughout the Americas and the Caribbean, the confinement of women to the household for free labor. Though not all contemporary evils are the result of capitalism, they have all been shaped by capitalism. Primordial prejudices and mistreatment of “aliens” has been around for a long time, but anti-black racism and “scientific” racism developed out of the economic functions of slavery and capitalist development; though patriarchy predates capitalism considerably, it has been absorbed and reproduced by capitalism’s dynamics.

One of the common selling points for capitalism is the voluntary character of the contracts, but again, I don’t think it’s a meaningful choice when your other options are “starve” and “beg.” But let’s grant that people enter into voluntary employment contracts to sustain themselves. Within those contracts, bosses behave like dictators, and this is a pattern of both small businesses and large corporations precisely because they want to get as much work and value out of you as they can in order to make a profit. (Vivek Chibber’s book Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital, while not about interpersonal domination by capitalists and employers, has a great chapter on the subject - “Capital’s Universalizing Tendency.”)

Now, although the standard of living and wages for American workers has been rising for a long time (only recently stagnating despite the growth in productivity, again the result of the neoliberal turn in the 70s and 80s), we have seen the most brutal forms of exploitation and domination displaced to other places - Southeast Asia, China, India, and Latin America being the most prominent cases. And still, as the article linked above demonstrates, there are lots of forms of interpersonal domination still going on in an American context.

B) Capitalism is anti-democratic. The concentration of wealth into a select few hands, and the associated political and social power that has become attached to greater social wealth, means that wealthier people have greater access to political power and influence. The Koch Brothers are probably the best example of this, though lobbying in general is an expression of this function. I’m not going to spend a lot of time on this one because I think it’s the least compelling argument personally even though I agree with it, but it is a popular and common one!

C) Capitalism is also fundamentally irrational. I think this is true in the way that we think about value and the way capitalism generates regular crises, but I’ll just use one example.

The convenient thing about money, as both Locke and Marx point out, is that it is potentially infinite unlike other resources. There is the possibility of limitless growth, of maximum expansion - which is why the capitalist mode of production began in Western Europe and the United States and has since spread around the world. (There is, of course, no such thing as limitless growth for anything, except perhaps cancer.) But capitalism takes this possibility as gospel and as a result, will do anything to maximize growth.

Sometimes those things are good for working people (farm subsidies enabling cheap food - though without those subsidies there would probably be a famine from capitalists not investing capital in food production). More often they aren’t, whether that’s mistreatment of workers, lowering or stagnating wages, destruction of the environment, or outright warfare. Plus, because there is a limit to natural desires or even luxury desires, capitalists have to constantly concoct new desires for us to latch onto, which is why so much money is sunk into advertising.And this is not merely the result of the ethical whims or personal behaviors of individual capitalists (though those do factor in), but the necessary and logical result of a mode of production that has an internal logic of constant, endless reproduction.

Why is the US also bad? how would you respond to someone who claims that it is a “free country” and that we “at least have the freedom of speech and the freedom to protest”, etc.

This is, paradoxically, an easier argument to make empirically but a harder case to sell because American nationalism and American exceptionalism are pretty ubiquitous, and they’ve only gotten more intractable in the past four or five decades. It really depends on what you mean by “bad,” anyway. On one level, the United States is not that different from any other state historically (since they are usually founded through violence and domination) or contemporarily (since they all act in their own geopolitical interests, and that often means fucking other people over undeservedly).

But, on another level: The United States- were built on indigenous and later African slavery- regularly violated treaties or used duplicitous means to gain access to Native American land for investment and expansion purposes- deployed genocidal tactics and sexual violence against Native Americans throughout the expansion process (especially in California and the Southeast)- fabricated a reason to wage war on Mexico to seize territory from it- botched Reconstruction after the end of formal slavery while still allowing black Americans to be abused and exploited and criminalized en masse- had racial policies that the Nazis found inspirational- engaged in imperialist warfare in the Caribbean at the turn of the century- overthrew the Kingdom of Hawaii for economic reasons- nuked a Japanese civilian target (TWICE) when their surrender was already in the cards- used its new hegemony to start launching coups against (mostly democratically elected and socialist-leaning) governments (Iran, Guatemala, Chile)- held the rest of the world in a hostage situation alongside the Soviet Union by threatening nuclear annihilation- waged war on Vietnam after violating the agreement to allow democratic elections and unification to take place- illegally bombed Cambodia and enabled the Khmer Rouge to gain traction- financed Islamist fighters against the Soviet Union that were the precursors of al-Qaeda- engaged in Iran-Contra, basically the shadiest thing in existence, and failed to deliver any real consequences to the people involved - supported and continues to support dictators (Batista, Saddam Hussein, etc.) as well as death squads (right-wing paramilitaries in Latin America)- has the highest incarceration rate in the world- has massively expanded the surveillance and police apparatuses since 9/11- invaded Iraq under false pretenses and let Islamic State develop out of the chaos

This is just a minor selection. And to top it all off, the Constitution of the United States is designed to make government as dysfunctional and anti-democratic as possible. The powers of the President have been perpetually expanding for a long time, and the Supreme Court is such a shamelessly broken, unaccountable institution that I cannot believe we take it seriously. The Supreme Court’s rulings on free speech have been up-and-down, often determined by war and nationalism, and the social backlash and hostility to political protest every time the United States goes to war suggests that even with the freedom of assembly granted by the Constitution, nationalism takes priority over freedoms.

This post is long enough, but if you (or anyone else) want me to elaborate on anything I’ve said here, feel free to ask.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

what will we do, expecting no reward?

The copy on the back cover of Elisa Gabbert’s The Unreality of Memory asks a question: “Can we avoid repeating history?”

The answer to that question lies in determining what we’ve been doing thus far and changing it. But many of the essays in the collection focus on the possibility of empathy and compassion at the expense of much discussion of what these feelings might help us to do. See for instance Gabbert, at the end of the essay “I’m So Tired,” growing maudlin over the state of the world until her activist friend justly snaps at her to “Stop despairing! That’s not a strategy.” Some time later, he relents; he grants that writing may be her form of activism. Should it be? Maybe we’ve really reached the end of what “personal essays” can achieve for either those who write them or those who read them.

Many of the essays in The Unreality of Memory are about the anxiety that the average middle-class person—the person who has a job in an industry like marketing or tech, has a healthy social life, keeps herself reasonably informed, and makes sure to vote—feels when she considers natural disasters, climate change, war, and mass death. Because this person is seldom at risk herself, the regard for others she experiences is often nominal rather than meaningful. “Worry, like attention, is a limited resource,” as Gabbert says in the essay “Threats,” and what we do with it depends on how immediate the threat we face is and whether it poses a risk to our individual survival. Often, we offload our worry onto experts who can tell us, for instance, where and how to build a structure to keep it safe from earthquakes.

But offload too much of your worry, leave too much of your responsibility for experts and systems to take up, and when a crisis comes that no one set of experts can address, you’re reduced to paralysis.

And there are limits to what any one expert can address when the crises and the systems wracked by them are big enough. When he was president, Barack Obama was a symbol of the systems, domestic and international, that claim to represent us and to work for our collective welfare. In the essay “In Our Midst,” Gabbert shares Obama’s response to a reporter’s question about South Sudan at one of his final press conferences:

Mike, I always feel responsible. I felt responsible when kids were being shot by snipers. I felt responsible when millions of people had been displaced. I feel responsible for murder and slaughter that’s taken place in South Sudan that’s not being reported on, partly because there’s not as much social media being generated from there. There are places around the world where horrible things are happening and because of my office, because I’m president of the United States, I feel responsible. I ask myself every single day, is there something I could do that would save lives and make a difference and spare some child who doesn’t deserve to suffer. So that’s a starting point. There’s not a moment during the course of this presidency where I haven’t felt some responsibility.

Gabbert takes this in good faith, as a genuine reflection of Obama’s deep capacity for care. I found it harder to do that. Reading the passage in 2020, I think: Is this expression of care anything more than mere expression? Did Obama work to stop what happened in South Sudan, or did he just feel bad about it?

I grant I’m overestimating the ability even the US president has to act to regulate conflicts fueled by global interests—not least that of the country he leads. The problem is probably the question Obama was asked. “Do you, as president of the United States, leader of the free world, feel any personal moral responsibility now at the end of your presidency for the carnage we’re all watching in Aleppo, which I’m sure disturbs you?” To that, I think: The president can feel as much personal moral responsibility as he likes. What will the systems around him let him do with that responsibility?

So often when we consider global catastrophes or natural disasters as responsible, empathic, suffering individuals, we end up stuck pathetically in the realm of affect. We know things are bad and we need to act to change them and we have no idea how. We don’t know what action even a president could take that would cut these knots we’ve so long tied. All we can do is talk about how bad it feels to be stuck—our fears and obligations and how it feels to contemplate them.

By the time we reach the epilogue of Unreality—a book written by an essayist considering the idea of catastrophe as an anxious, curious, empathic, suffering individual—Gabbert’s investigations culminate in banalities. “I don’t think most people are good, or bad, for that matter,” Gabbert says. “I think most people are neutral”:

It seems to me that “good people” can become “bad people” when provided the opportunity within an existing power structure—to claim and exert power at a deadly cost to others and get away with it.

I don’t think Gabbert needed to write this whole book to come to that conclusion. That could’ve been the premise she started from.

It led me to think we probably don’t need essayists to comment on this moment at all; all essays about how our current moment feels will be empty, reflexive, performative gestures that just don’t need to be made. And what we really need are critics and theorists who can give activists and laypeople an understanding of the power structures they live in and identify concrete ways to make those structures change, stop the people who exert power within them, and hold those people accountable.

In the epilogue to the book, as she considers the question of what we can ever know of the world, Gabbert writes of her attraction to the German biologist Jakob von Uexhull’s idea of the Umwelt—which is the name he gives to the information an animal picks up from its surroundings, often limited to just what the animal can sense given the equipment it has and what it immediately needs. Think of a tick: all it knows to pay attention to is the temperature and particular odors that will help it find blood. “Like a tick or a bat,” Gabbert adds, “we only know what we know.” But that seems wrong. At the risk of stating my own banality here, humans aren’t ticks or bats. They’re humans. They’re the one creature on this planet with a mind that is equipped to know what it doesn’t know and what it’ll need to figure out. And to pretend otherwise feels like dithering as we approach an event horizon.

I know Gabbert doesn’t have any answers to the questions of climate change or war or putatively democratic systems that no longer respond to the will of the people. No one person does. But to do so much pontificating instead is frustrating.

But I don’t mean to pile on. I’m essentially in Gabbert’s position myself. I didn’t go to many of the past summer’s protests either; I was generally too leery of getting or spreading COVID. I regularly write and think and talk more about problems I see than I act in ways that might solve those problems. I generally enjoyed this book. And I’m generally sympathetic to the authors accused of falling into the reflexivity trap—Katy Waldman’s term for the idea, often implied in contemporary essays and works of autofiction, that to be aware of your own privileged position is to be absolved of it; that awareness alone is sufficient. I liked Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror; I liked Anna Wiener’s Uncanny Valley; I like Sally Rooney’s novels, basic though they might be, even as the ranks of today’s literary critics have closed around the positions that her books don’t bear out her politics and aren’t worth the time the mainstream press gives them. Or more accurately, I feel empathy for those writers, and for Gabbert. I suspect we were formed by the same pressures.

Many of us writing today grew up under similar narrow, capitalist, rightward political horizons; we were given the same withered political vocabularies and feeble political imaginations. And so, today, there are many artists whose work doesn’t really reflect their stated politics; there are many (left) positions that are more easily stated than lived; there are many changes we want to see in this world that we have no real way to make. And often, all we can do is say how much we want to make them and confess over and over that we can’t. Doesn’t an individual’s ability to effect change depend on whether systems respond to her efforts? And do ours? To what extent can political orientations or commitments to combat climate change be meaningfully lived when political life for so many is voting once or twice every few years, for politicians who don’t listen to us or can’t or won’t deliver what we need, while systems stay gridlocked?

In her review of Trick Mirror, Lauren Oyler wrote that what people in the reflexivity trap often do is shield what is really a demonstration of their priorities and desires under the guise of “surviving” in a compromised world. And as Amber Husain wrote in The White Review, the sort of informed exceptionalism exhibited by Jia Tolentino or Anna Wiener, the apparent belief that if you write convincingly perceptively about the morally compromised systems you participate in, you can avoid being held to account for that, is not enough.* You have to interrogate your own desires, refuse to indulge the ones that make you complicit in an unethical world, and consciously choose to satisfy desires and imperatives that are productive or just. Having read The Unreality of Memory, I feel the desire to write about how we feel when we think about, say, the climate changing, the desire to dramatize that feeling, isn’t a productive desire. But it feels that way. And because it ends in a result, in a concrete thing like an essay or a book, it feels better than the impossible work of trying to act in a way that might curb climate change or mitigate the damage of our next fire season. That work, by contrast—it’s hard to figure out what it would look like. And just contemplating the issue is unsatisfying, difficult, grinding, humiliating. It hurts.

But that’s a pain we need. I think also of a recent conversation between Donald Glover and Michaela Coel in GQ, in which Glover says, “Every generation has a job they need to do,” and “the job is always the same, which is to plant a tree you won’t eat from.”

...you need to plant a tree right now. And you don’t get to eat from it. Maybe your kids don’t even get to eat from it. You just teach them to water it, but their kids get to eat from it. And you do or you go on, you transition, knowing you did the right thing.

Enough about how we feel; we know the answer is “bad.” And on to the question: what will we do, expecting no reward?

*The connections I’ve made here come courtesy of Haley Nahman’s “Maybe Baby” column: specifically, “#24: The Emily Ratajkowski effect,” in which Nahman writes about Emily Ratajkowski’s “Buying Myself Back” and the position of the culture worker who both profits from the culture and agitates against it. I��d read both Oyler’s piece and Husain’s as they came out, but I hadn’t made the connection until I saw it so well elaborated by Nahman.

#books#literary#essays#elisa gabbert#lauren oyler#amber husain#haley nahman#climate change#sally rooney#the reflexivity trap#katy waldman#barack obama#jia tolentino#anna wiener#donald glover#michaela coel

1 note

·

View note

Text

Divest From the Video Games Industry! by Marina Kittaka

https://medium.com/@even_kei/divest-from-the-video-games-industry-814a1381092d

This piece seeks to contextualize the problems of the video games industry within its own mythology, and from there, to imagine and celebrate new directions through a lens of anti-capitalist and embodied compassion.

My name is Marina Ayano Kittaka (she/her), I’m a 4th gen Japanese American trans woman from middle class background. I work in a variety of different art forms but my bread and butter are the video games I make with my friend Melos Han-Tani, e.g. the Anodyne series.

I am not an authority on any of these topics, and it’s not my intention to speak over anyone else or offer comprehensive solutions, only to be one small piece of a larger conversation and movement. I use declarative and imperative sentences for clarity, not certainty.

I seek to follow the leadership of BIPOC abolitionist thinkers such as Ejeris Dixon, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, adrienne maree brown and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, along with the work of local (to me) groups like Black Visions Collective and MPD150. I welcome feedback, especially if you believe that something I’ve said is harmful.

This piece is inspired by the latest wave of survivors bravely sharing their stories (it is June 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic and global uprising against anti-Black racism and the unjust institution of police). I believe and stand with survivors.

The Problems

The video games industry has many deep, tragic, and intertwining problems. It’s beyond the scope of this piece to examine the entirety of games culture (I will focus on development and, to a lesser degree, distribution). It’s also beyond the scope of this piece to convince anyone that these problems exist, but I’ll be moving forward with the assumption that we agree that they do. Here is an incomplete list:

Pervasive sexual abuse

Workplace abuse, bullying, crunch, burnout, generally exploitative labor conditions

Sexism, racism, and other bigotry — the above abuses are accentuated along these intersections (e.g. the sexual abuse of marginalized genders or the exclusion of racial minorities).

Supply chain problems including conflict minerals and exploitative factory conditions

Heavy environmental impacts

Non-Judgement

This conversation may spark hurt or defensive feelings. I want to address this directly. Many people love video games, and not only that, but are deeply invested in the world of games. I’m particularly sensitive to marginalized creators who have fought hard to find a foothold in the games industry and deserve to follow their dreams. I exist more on the periphery of the games industry and my goal is not to center my personal anger or disdain — but instead to push toward a world with better games, played by happier audiences, made by creators who feel safe and appreciated.

Additionally, this conversation is not about the merits of any individual AAA (large studio) game. It’s not about creating strict rules about media consumption. It’s not about shaming people into certain beliefs or behaviors. When we try to act like our personal tastes must align with our most high-minded ideals, we encourage shame or denial — things that distance us from others.

Nor is this exclusively about AAA. This is about any situation where the power becomes the point. There can be gradations of industrial complexes and power complexes existing from the smallest micro-communities to the largest corporations. We can divest on all levels.

The Industry Promise

I believe that many of us as game creators and audiences have (consciously or not) bought into the idea that happiness and wonder are scarce and fragile commodities — precious gems mined via arcane and costly processes. Life can often be isolating, alienating, and traumatic, and many of us cope by numbing some parts of ourselves¹. The poignance and pleasure of simply feeling becomes rare.

In answer to this perceived scarcity, The Industry swoops in with a promise that technological and design mastery can “make” people feel. It does this not only blatantly in marketing copy or developer interviews, but also in unwieldy assertions that games can make you empathic, or through the widespread notion that games are an exceptionally “immersive” art form due to “interactivity”. Embedded in this promise is the ever-alluring assumption that technological progress is linear: games overall must be getting better, more beautiful, more moving, because that is simply how technology works! Or perhaps it is the progress itself that is beautiful — each impressive jump towards photorealism delivering the elusive sense of wonder that we crave.

At this point, I could argue that the benefits are not worth the cost, that the aforementioned Problems outweigh even this idealized vision of what games provide. But I’m guessing many of you might find that unsatisfying, right? Why don’t we simply reform the system? Spread awareness and training about sexism and racism, create more art that engenders empathy, encourage diversity? Isn’t it throwing the baby out with the bathwater to “halt” technological progress in order to fix some issues of bad leadership here or abusive superstar there?

Here we come to my main purpose in writing this piece: to expand the imaginative space around video games by tearing out The Industry Promise at its roots. If wonder is not scarce and progress is not linear, then the world that rises from the ashes of the Video Games Industry can be more exciting and more technologically vibrant than ever before.

Precious Gems

Take a deep breath and picture some of the happy moments of your life. Maybe some of them look like this:

Staying up late and getting slaphappy with a friend; looking out over a beautiful landscape; a passionate kiss; collaborating with friends in a session of DnD or Minecraft; a thoughtful gift from someone you admire; a cool drink on a hot summer day; making a new friend who feels like they really see you; singing a song; a hug from someone who smells nice; getting junk food late at night and feeling naughty about it; the vivid colors and sounds of a rainy city evening; drifting to sleep in the cottony silence of a smalltown homestead; getting a crew together to see a new movie; the scent of the air at sunrise; having a meaningful conversation with a nonverbal baby.

Picture the games you loved most as a child, the games that felt full of possibility and mystery and fun. Were they all the most technologically advanced? The most critically revered?

Maybe your happy moments look nothing like this. Or maybe you can’t recall feeling happy and that’s the whole problem. But my point is that happiness, joy, fun… these things are at their core fluid, social, narrative, contextual, chemical. In both its best and most common incarnations, happiness is not shoved into your passive body by the objective “high quality” of an experience. Both recent psychological research and traditions from around the world (e.g. Buddhist monks) suggest that happiness and well-being are growable skills rooted in compassion.

Think of all the billions of people who have ever lived, across time, across cultures, with video games and without, living nomadically or settling in cities or jungles. In every moment there are infinite reasons to suffer and infinite reasons to be happy². Giant industry’s monopolistic claims to “art” or “entertainment” have always been a capitalist lie, nonsensical yet inescapable.

The Narrative of Technology and Progress

Is this an anti-technology screed? Am I suggesting we must all go outside like in the good old days and play “hoop and stick” until the end of time? Let’s start by unpacking what we mean when we say “technology”. Here’s one definition:

Technology is the sum of techniques, skills, methods, and processes used in the production of goods or services or in the accomplishment of objectives.

— Wikipedia

Honestly, technology is such a vague and broad concept that nearly anything anyone ever does could be considered technological! As such, how we use the term in practice is very revealing of our cultural values. Computing power, massive scale, photorealistic graphics, complex AI, VR experiences that attempt to recreate the visual and aural components of a real or imagined situation… certainly these are all technologies that can and have grown in sophistication over time. But what The Industry considers technological progress actually consists of fairly niche goals that have been artificially inflated because capitalists have figured out they can make money this way. Notably, I don’t use “niche” here as an insult — aren’t many of the most fascinating things intrinsically niche? But when one restrictive narrative sucks all the air out of the room and leaves a swath of emotional and physical devastation in its wake… isn’t it time to question it?

What if humans having basic needs met is “technological progress”? What if indigenous models of sustainable living are “hi-tech”? What if creating a more accessible world where people have freedom of movement opens up numerous high-fidelity multisensory experiences? These questions go far beyond the scope of the video games industry, sure, but in the words of adrienne maree brown, “what we practice at the small scale sets the patterns for the whole system”³.

What We Hope to Gain

The kneejerk reaction to dismantling an existing structure tends to be a subtractive vision. Here we are, living in the exact same world, but all blockbuster video games have been magically snapped out of existence… only hipster indie games remain! Missing from this vision is the understanding that our current existence is itself subtractive — what we cling to now comes at the expense of so much good. The loss of maturing vision and skill when people leave the industry due to burnout, sexual assault, and racist belittlement. Corporate IP laws and progress narratives that disincentivize preservation and rob us of our rich and fertile history. The ad-centric, sanitized, and consolidated internet that chokes out democratized community spaces. The fighting-for-scraps mentality that the larger industry places on small creators with its sparing and self-interested investment. Our current value system limits not only what AAA games are but also what everything else has the capacity to be.

Utopia does not have an aesthetic. We don’t need to prescribe the correct “alt” taste. Games can be high and low, sacred and profane, cute and ugly, left brain and right. Destroying the games industry does not mean picking an alternate niche to replace it. Instead, we seek to open the floodgates to a world in which countless decentralized, intimate, and overlapping niches might thrive.

When we decentralize power, we not only create the conditions for more and better games, we also diminish the conditions under which abuse can flourish. Many of the stories of abuse hinge on the abuser wielding the power to dramatically help or harm the careers of others. The consolidation of this power is enhanced by our collective investment in The Industry Promise (not forgetting the wider cultural intersections of oppression). Mythologized figures ascend along a linear axis of greatness, shielded by the horrifying notion that they are less replaceable than others because their ranking in The Industry evidences their mystical importance.

What’s Next?

Here is a fundamental truth: we do not need video games. Paradoxically, this truth opens up the world of video games to be as full and varied and strange and contradictory as life itself.

So. Say you agree with all or part of my assertions that collectively we may proceed to end the video games industry by divesting our attention, time, and money, and building something new with each other. But what does that look like in practice? I don’t have all the answers. I find community very difficult due to my own trauma. Nonetheless, I’ll do some brainstorming. Skim this and read what speaks to you personally, or do your own brainstorming!

Center BIPOC/queer leadership

I.e. people who have been often forcibly divested from the majority culture and have experience in creating alternatives. Draw on influences outside of media e.g. transformative justice, police abolition, and prison abolition. Books like Beyond Survival and Emergent Strategy are based in far deeper understanding of organizing than anything written here, and are much more relevant to the direct and immediate issues of things like responding to sexual assault in our communities.

Divest from celebrity/authority

Many people will tell you that their most rewarding artistic relationships are with peers, not mentors and certainly not idols. Disengage from social media-as-spectator sport where larger-than-life personalities duke it out via hot take. Question genius narratives wherever they arise. Cultivate your own power and the power of those adjacent to you. If you feel yourself becoming a celebrity: take a step back, recognize the power that you wield over others, redirect opportunities to marginalized creators whose work you respect, invest in completely unrelated areas of your life, go to therapy.

Divest from video games exceptionalism

Academics have delved into video games’ inferiority complex and the topic of “video games exceptionalism”, which is tied into what I frame as The Industry Promise above — the idea that video games as a technological vanguard are brimming with inherent value due to all the things they can do that other forms of media cannot. This ensures that gobs of money get thrown around, but it’s an ahistorical and isolating notion that does nothing to actually advance our understanding of games as a form (Interesting discussion on this here, which reminds me of Richard Terrell’s work regarding vocabulary).

Reimagine scale

Rigorously question the notion that “bigger is better” at every turn. With regards to projects, studios, events, continually ask “why?” in the face of any pressure to make something bigger, and then try to determine what might be lost as well as what might be gained. Compromising on values tends to be inevitable at scale, workplace abuse or deals with questionable entities. For me this calls to mind the research led by psychologist Daniel Kahneman suggesting that the happiness benefits of wealth taper off dramatically once a comfortable standard of living is reached. Anyone who’s ever had a tweet go viral can tell you that it’s fun at first and then it just becomes annoying. Living in a conglomerated, global world, we regularly have to face and process social metrics that are completely incomprehensible to the way our social brains are programmed, and the results are messy. Are there ever legitimate uses for a huge team working on a project for many years? Sure, probably, but the idea that this is some sort of ideal normal situation that everyone should strive for is based on nothing but propaganda.

Redefine niche

Above I suggest that AAA is niche. I believe it’s true broadly, but that it’s definitely true relative to their budgets. What do I mean by this? AAA marketing budgets are reported to be an additional 75–100% relative to development costs (possibly even higher in some cases). Isn’t this mindblowing? If a game naturally appealed to proportionately mass numbers of people by virtue of its High Quality or Advanced Technology, then would we really need to spend tens or hundreds of millions of dollars just to convince people to play it? For contrast, Melos estimates that our marketing budget for Anodyne 2 was an added 10% of development costs and it was a modest commercial success. Certainly marketing is a complex field that can be ethical, but to me, there is something deeply unhealthy about the capacity of large studios to straight up purchase their own relevance (according to some research, marketing influences game revenue three times more than high review scores).

On a separate but related note, I don’t buy that all the perceived benefits of AAA such as advancements in photorealism will vanish without the machine of The Industry to back them. People are astonishing and passionate! It won’t always necessarily look like a 60 hour adventure world, but it will be a niche that we can support like any other.

Ground yourself in your body

Self-compassion, mindfulness, meditation, exercise, breathing, nature, inter-being. There are many ways to build your capacity to experience joy, wonder, and happiness. One of the difficult things about this process though is that if you approach these topics head on, you’ll often be overwhelmed with Extremely Specific Aesthetics that might not fit you (e.g. New Agey or culturally appropriative). My advice is to 1) be open to learning from practices that don’t fit your brand while also 2) being able to adapt the spirit of advice into something that actually works for you. The benefit of locating our capacity for joy internally is that it reveals that The Industry is fundamentally superfluous and so we are free to take what we want and throw the rest in the compost pile.

As a side note, some artists (who otherwise have structural access to things like mental health services) fear becoming healthy, because they’re worried that they will lose the spark and no longer make good art. Speaking as an artist whose creative capacity has consistently increased with my mental health, there are multiple reasons why I don’t think people should worry about this.

You carry your past selves within you, even as you change. “Our bodies are neural and physiological reservoirs of all our significant experiences starting in our prenatal past to the present.”⁴

You can lose a spark and gain another. You can gain 6 sparks in place of the one you lost.

What is it that you ultimately seek from being “good at art”? Ego satisfaction? Human connection? Self-respect? All of these things would be easier to come by in the feared scenario in which you are so happy and healthy that you can no longer make art. Cut out the middleman! Art is for nerds!

Invest outside of games