#Elisha Kirkall

Text

Shakespeare Weekend

We are halfway through Nicholas Rowe’s (1674-1718) The Work of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes! Published in London in 1709 by Jacob Tonson (1655–1736), this second edition holds an important place within Shakespearean publication history. The Work of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes is recognized as the first octavo edition, the first illustrated edition, the first critically edited edition, and the first to present a biography of the poet.

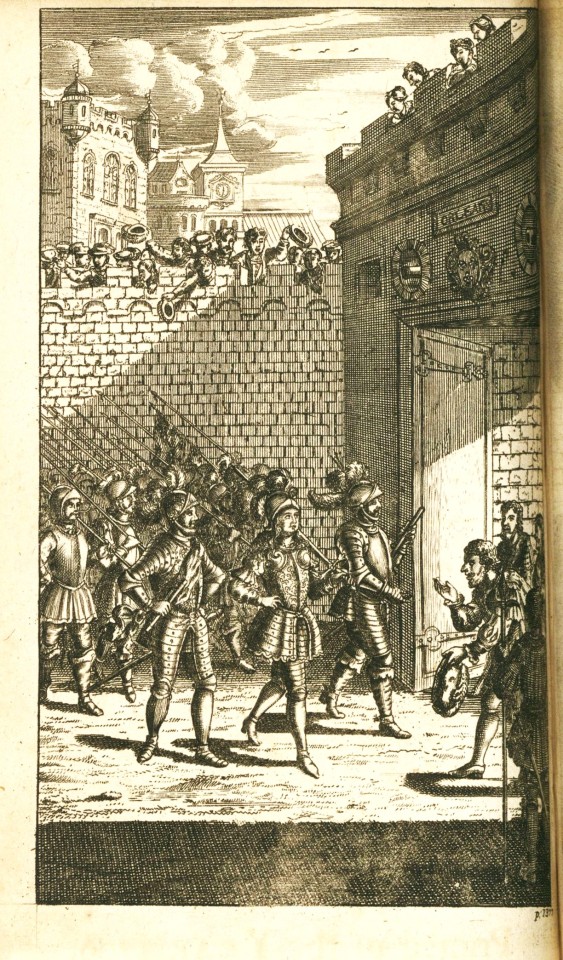

This week, we explore the third volume of The Work of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes. The third volume encompasses historic plays including a Shakespearean Henriad depicting the rise of English kings. The volume is comprised of King John, King Richard II, Henry IV Part I, Henry IV Part II, King Henry V, King Henry VI Part I, and King Henry VI Part II. While the plays have recurring characters and settings, there is no evidence that they were written with the intention of being considered as a group. A full-page engraving, designed by the French Baroque artist and book illustrator François Boitard (1670-1715) and engraved by English engraver Elisha Kirkall (c.1682–1742), precedes each play.

In addition to Rowe’s editorial decisions to divide the plays into scenes and include notes on the entrances and exits of the players, he also normalised the spelling of names and included a dramatis personae preceding each play. The only chronicled critique of Rowe’s momentous editorial endeavor is his choice in basing his text on the corrupt Fourth Folio.

View more volumes of The Works of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes here.

View more Shakespeare Weekend posts.

-Jenna, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#shakespeare weekend#nicholas rowe#the works of mr. william shakespear#king john#king richard II#Henry IV#King Henry V#King Henry VI#jacob tonson#henriad#François Boitard#Elisha Kirkall#engravings

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Elisha Kirkall (c.1682–1742) - Apollo and Daphne.

0 notes

Photo

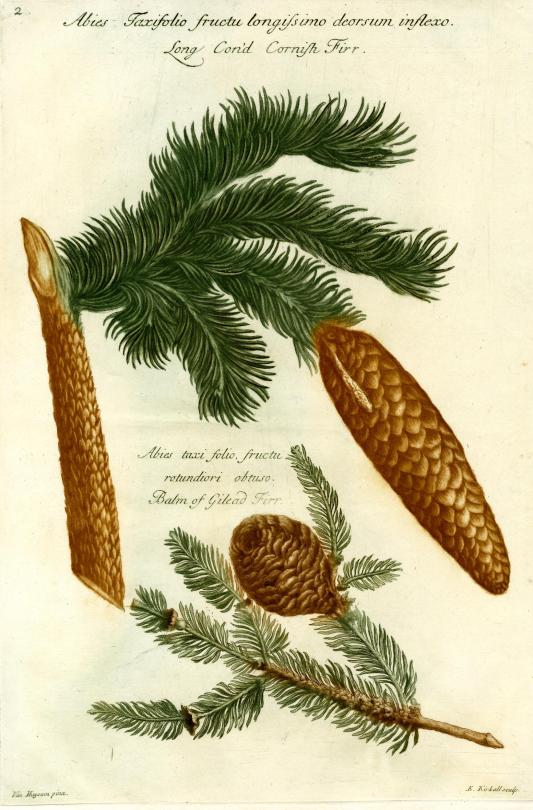

1) Three specimens of the Bermuda Cedar and of the Small Coned Fir tree.

2) Two specimens, one of the Pinaster, the other of the Large Cluster Pine.

3) Three specimens of the Larch tree in different stages of growth.

4) Two specimens, one of the Long Coned Cornish Fir tree, the other of the Balm of Gilead Fir.

Illustrations by Jacobus van Huysum taken from 'Catalogus Plantarum' of the Society of Gardeners of 1730. Mezzotints printed in colours. Prints made by Elisha Kirkall.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

457 notes

·

View notes

Photo

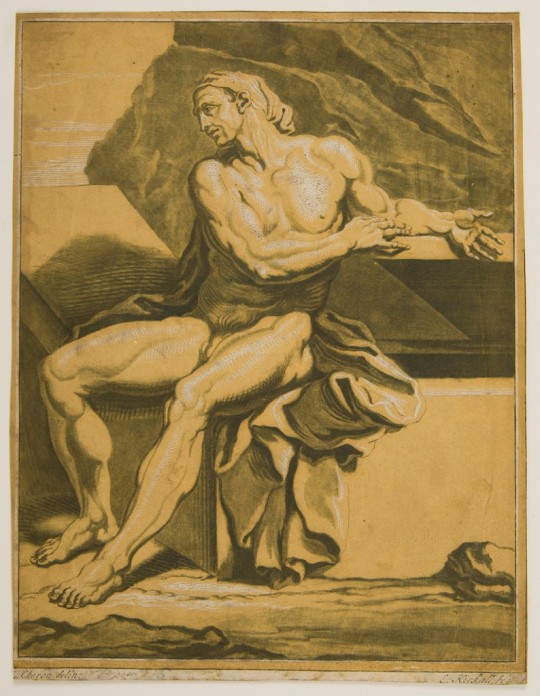

Seated Male Nude, Elisha Kirkall, c. 1725, Harvard Art Museums: Prints

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Belinda L. Randall from the collection of John Witt Randall

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/243698

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The brief history of Castrati - part three (part one, part two)

Serious opera in the first two-thirds or so of the 18th century was dominated by a succession of famous castratos, of whom Nicolo Grimaldi (’Nicolini’), Antonio Maria Bernacchi, Francesco Bernardi (’Senesino’), Carlo Broschi (’Farinelli’), Giovanni Carestini, Gaetano Majorano (’Caffarelli’) and Gaetano Guadagni are only the best known. Such artists could command engagements in one European capital after another at unprecedented fees - in Turin the primo uomo’s fee for the carnival season was sometimes equal to the annual salary of the prime minister - while they also kept, as insurance, permanent appointments in a monarch’s chapel choir or a cathedral, and some of them performed there regularly.

Their achievements are now difficult to gauge. Their command of vocal agility - of trills, runs and ornamentation, especially in the da capo section of an aria was clearly central to their success. So, at least for some, was a phenomenally wide range: Farinelli is said to have commanded more than three octaves (from c to d'''), others more than two, though, like some modern sopranos and tenors, they were apt to lose the upper part of their range as their careers wore on. It would, however, be a mistake to regard leading castratos as vocal acrobats and no more. Command of pathetic singing - soft, laden with emotion, powered by controlled devices such as messa di voce - was highly regarded: it was, for instance, central to the reputation of Gasparo Pacchiarotti. Nor was acting ability ignored: Guadagni’s performance as Gluck’s original Orpheus was thought deeply affecting. The issue is clouded by the habit of commentators through most of the 18th century of bemoaning the supposed decadence of opera through an excessive cult of vocalism and ornamentation. This was in part a literary convention. The cult flourished, and was in practice forwarded by some of those who decried it.

Another contemporary habit that needs to be guarded against is that of mocking the castratos as grotesque, extravagant, inordinately vain near-monsters. This was in part a nervous reaction against a phenomenon experienced as sexually threatening twice over: the fact of castration was disconcerting in itself, yet according to legend (held by most modern medical opinion to be baseless, though perpetuated, along with much traditional obfuscation, in the 1995 film Farinelli) castratos could perform sexually all the better for the loss of generative power. In part the mockery visited upon castratos was roused by highly paid star singers in general, among whom they were the most prominent. Because of their musical education they often did well as teachers; some who had also had a general education acted in retirement, or even during their singing careers, as antiquarian, booksellers, diplomats, or officials in royal households.

#source: the new grove dictionary of music and musicians#castrati#castrato#history#history of music#opera#opera seria#italian#Giovanni Carestini#francesco bernardi#Senesino#Carlo Broschi#Farinelli#gioacchino conti#gizziello#18 century#18 century art#18 century music

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

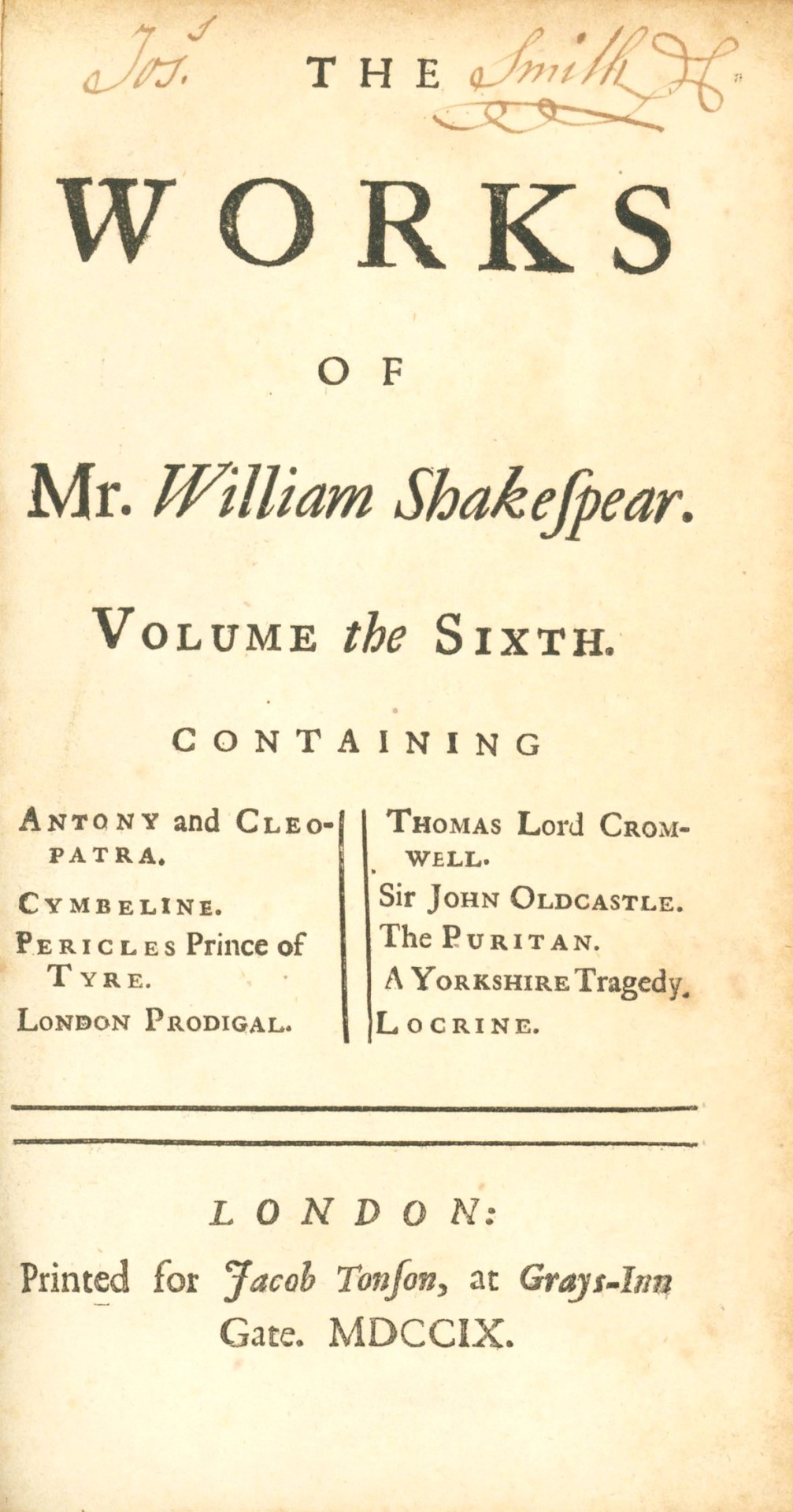

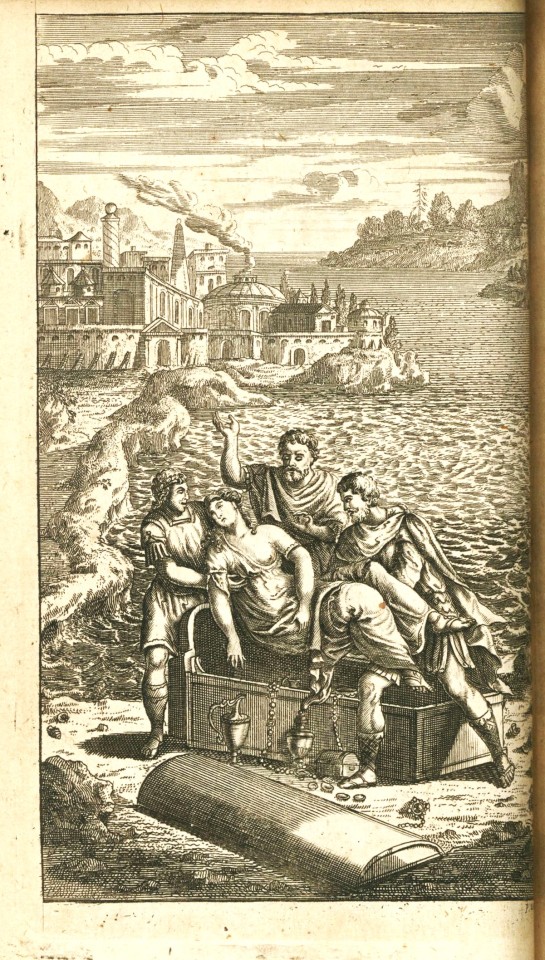

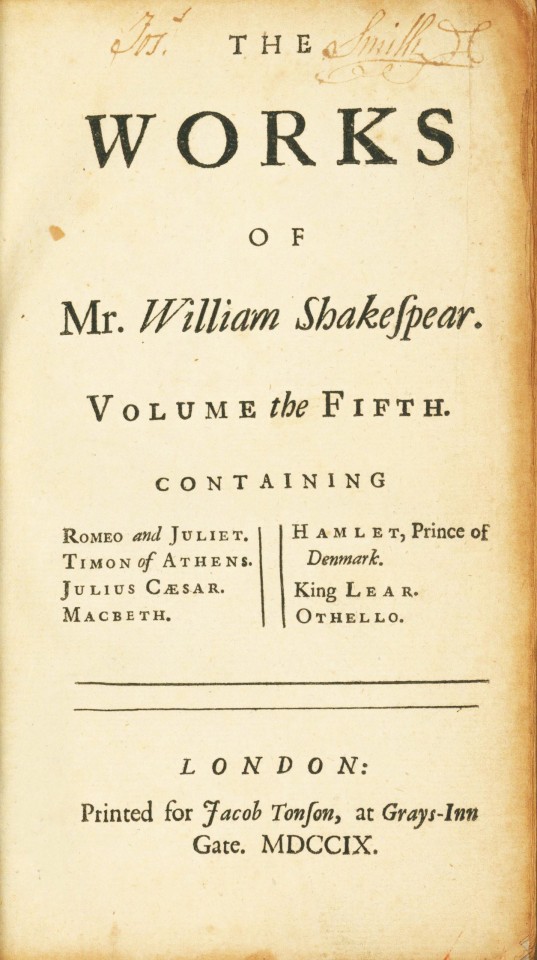

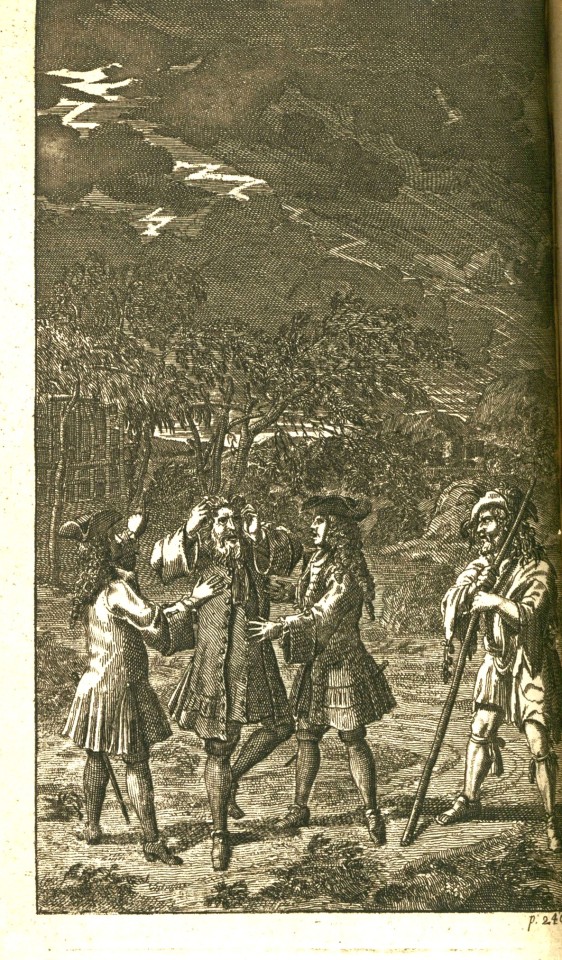

Shakespeare Weekend

This weekend we are wrapping up Nicholas Rowe’s (1674-1718) The Work of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes. Published in London in 1709 by Jacob Tonson (1655–1736), this second edition holds an important place within Shakespearean publication history. The Work of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes is recognized as the first octavo edition, the first illustrated edition, the first critically edited edition, and the first to present a biography of the poet.

Volume six is a collection of Shakespeare’s tragedies and comedies including several plays that are a part of the Shakespeare apocrypha that bear Shakespeare’s name, but do not appear in the First Folio and of which there is question about his role in writing them. Apocrypha in the sixth volume include Pericles Prince of Tyre, London Prodigal, Thomas Lord Cromwell, Sir John Oldcastle, The Puritan, A Yorkshire Tragedy, and Locrine. Volume six also includes confirmed Shakespearean plays Antony and Cleopatra and Cymbeline.

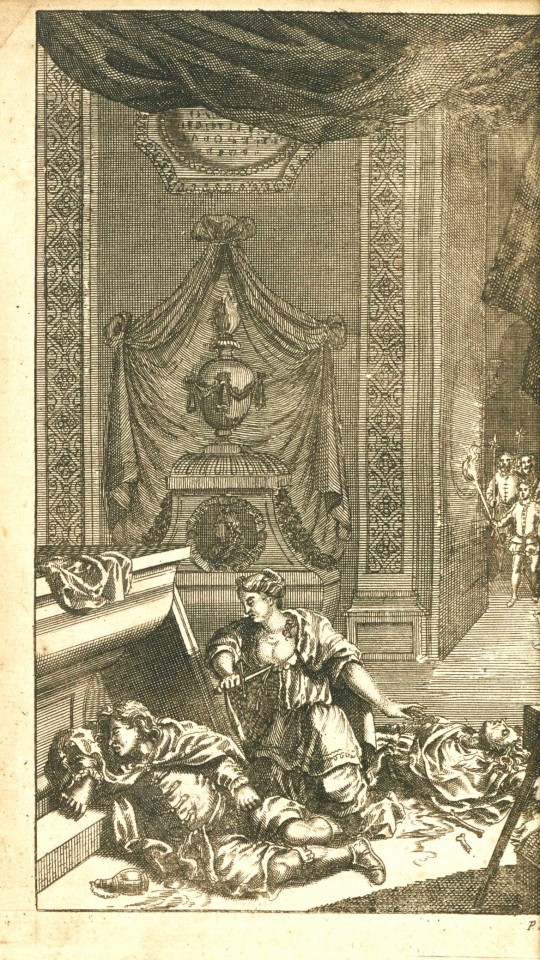

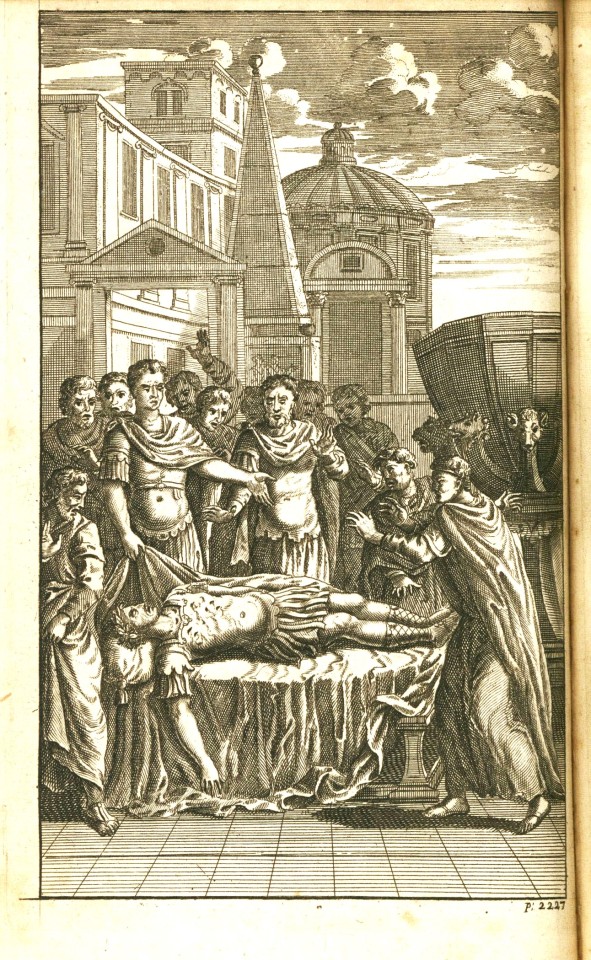

A full-page engraving by the French Baroque artist and book illustrator François Boitard (1670-1715) and engraved by English engraver Elisha Kirkall (c.1682–1742) precedes each play. Boitard’s illustrations often place readers at the pinnacle of the plays depicting high drama in his classic Baroque style.

In addition to Rowe’s editorial decisions to divide the plays into scenes and include notes on the entrances and exits of the players, he also normalised the spelling of names and included a dramatis personae preceding each play. The only chronicled critique of Rowe’s momentous editorial endeavor is his choice in basing his text on the corrupt Fourth Folio.

View more volumes of The Works of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes here.

View more Shakespeare Weekend posts.

-Jenna, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#Shakespeare Weekend#william shakespeare#shakespeare#mr. william shakespear in six volumes#nicholas rowe#jacob tonson#Shakespeare apocrypha#apocrypha#francois boitard#elisha kirkall#antony and cleopatra#cymbeline#pericles prince of tyre#london prodigal#thomas lord cromwell#sir john oldcastle#the puritan#a yorkshire tragedy#locrine

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

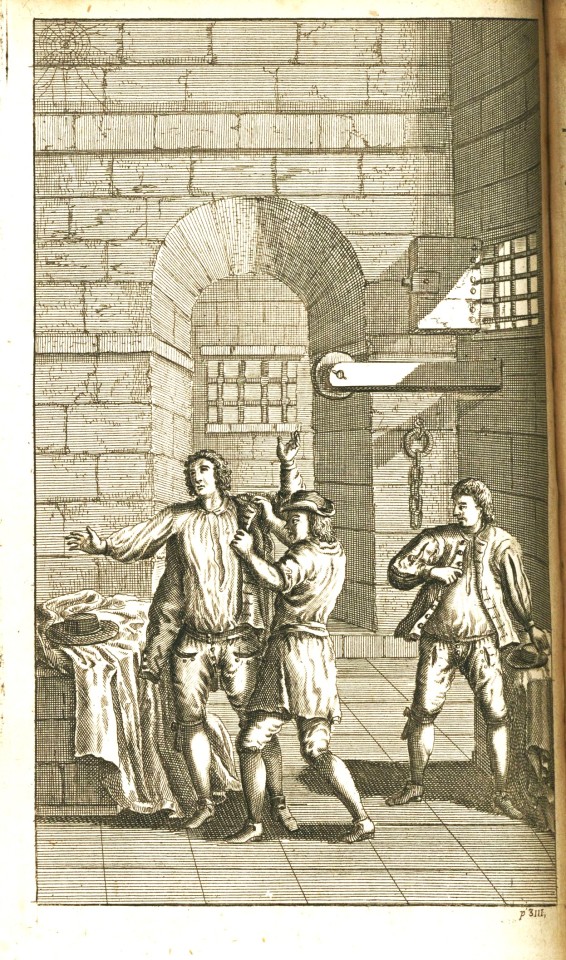

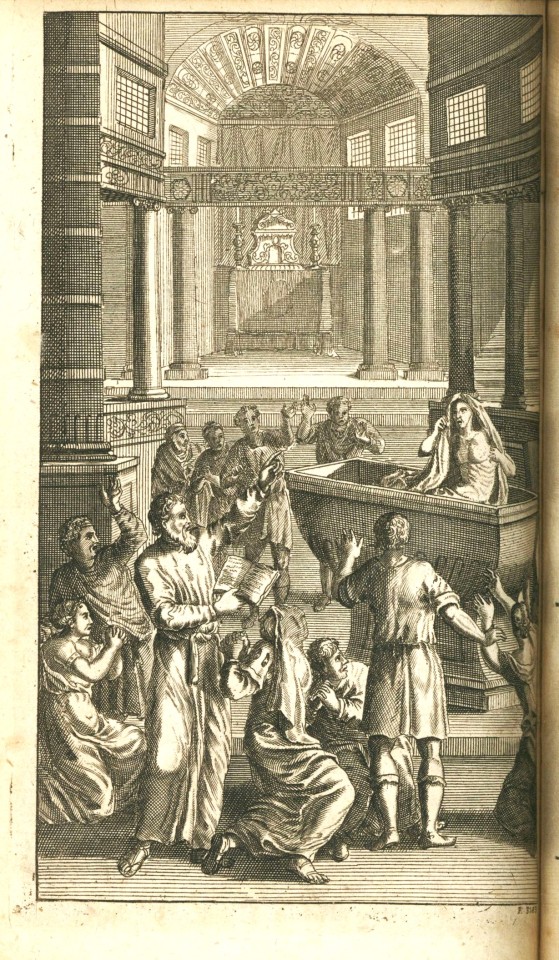

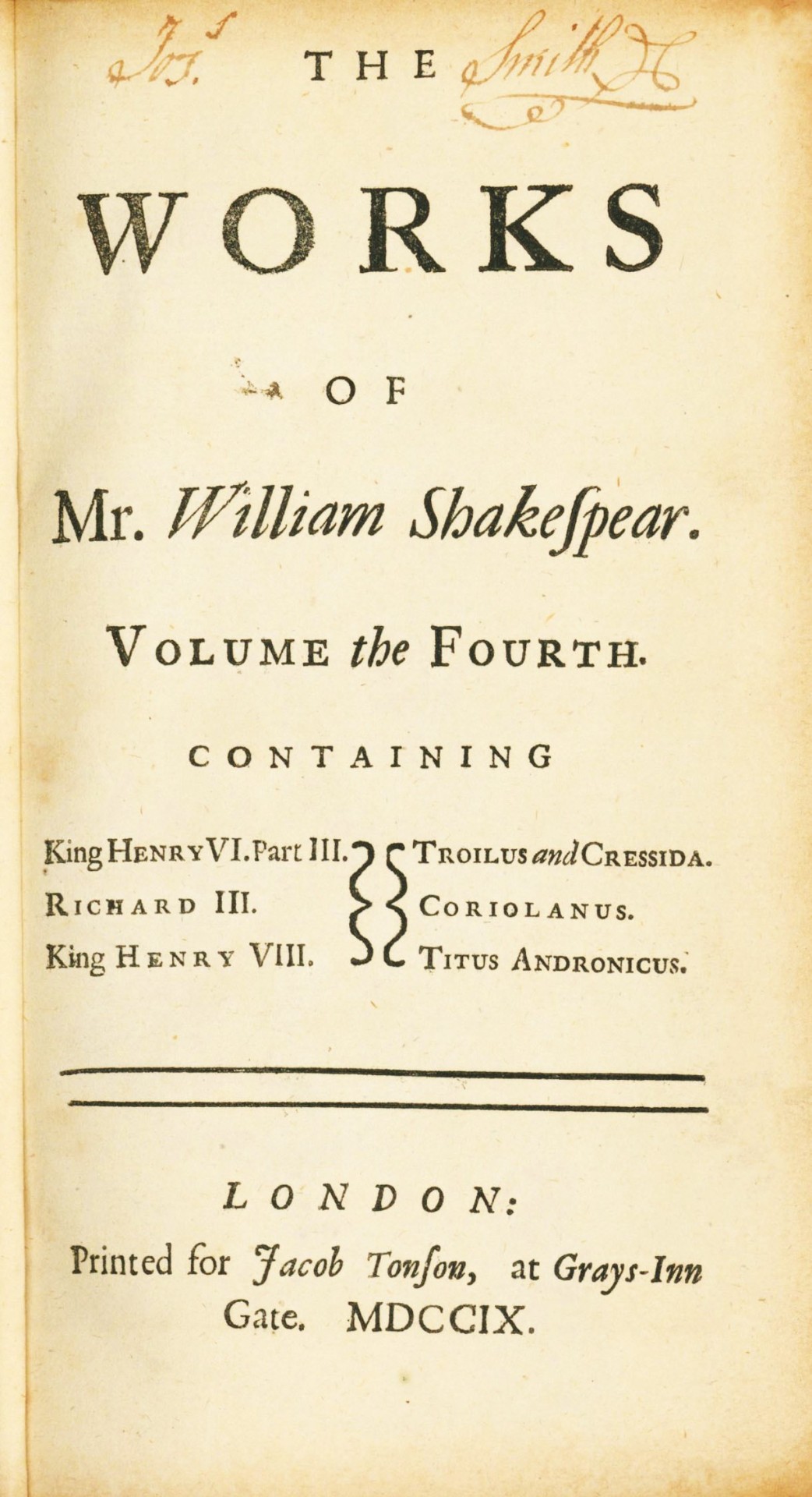

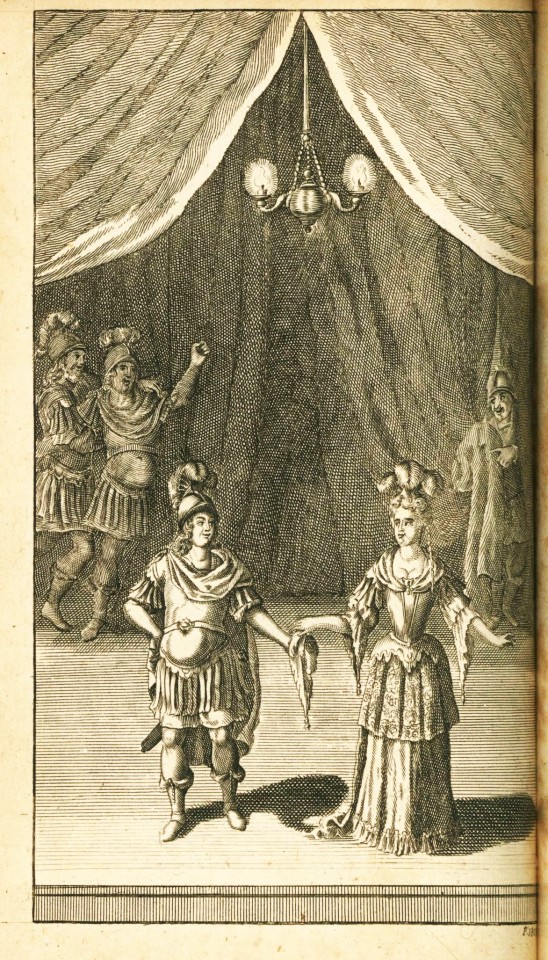

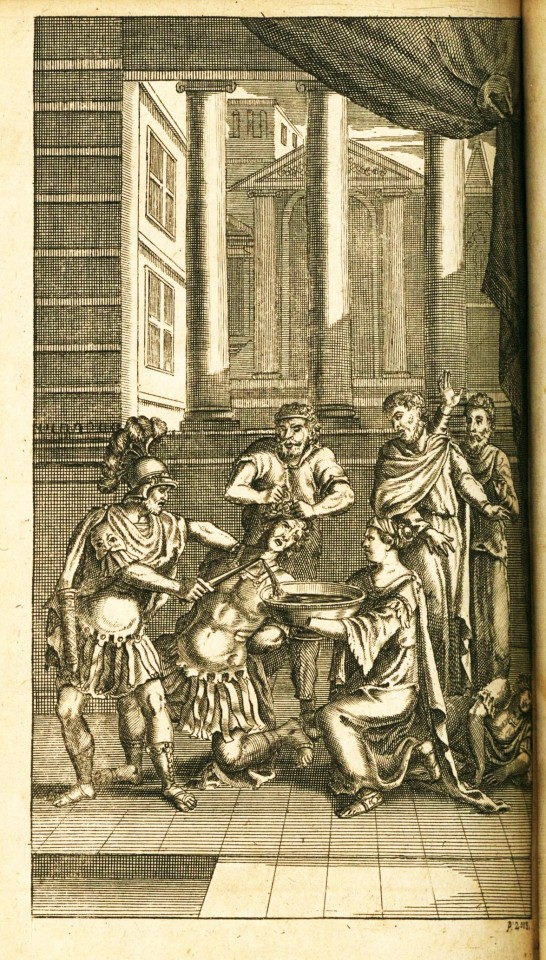

Shakespeare Weekend

This weekend we return to Nicholas Rowe’s (1674-1718) The Work of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes. Published in London in 1709 by Jacob Tonson (1655–1736), this second edition holds an important place within Shakespearean publication history. The Work of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes is recognized as the first octavo edition, the first illustrated edition, the first critically edited edition, and the first to present a biography of the poet.

Volume four picks up where volume three left off, returning readers to the Kings of England. The fourth volume begins with King Henry VI. Part III, known for having one of the longest soliloquies and more battle scenes than any other Shakespeare play. Following King Henry VI. Part III is Richard III and King Henry VIII. The volume concludes with three of Shakespeare’s tragedies; Troilus and Cressida, Coriolanus, and Titus Andronicus. A full-page engraving by the French Baroque artist and book illustrator François Boitard (1670-1715) and engraved by English engraver Elisha Kirkall (c.1682–1742) precedes each play. The Titus Andronicus engraving is particularly graphic, feeding the rumor that the play was Shakespeare’s attempt to emulate the violent and bloody plays of his contemporaries.

In addition to Rowe’s editorial decisions to divide the plays into scenes and include notes on the entrances and exits of the players, he also normalised the spelling of names and included a dramatis personae preceding each play. The only chronicled critique of Rowe’s momentous editorial endeavor is his choice in basing his text on the corrupt Fourth Folio.

View more volumes of The Works of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes here.

View more Shakespeare Weekend posts.

-Jenna, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#shakespeare weekend#nicholas rowe#the work of mr. william shakespear in six volumes#jacob tonson#king henry vi part iii#richard iii#king henry viii#troilus and cressida#coriolanus#titus andronicus#engravings#François Boitard#Elisha Kirkall

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shakespeare Weekend!

This weekend we come back to Nicholas Rowe’s (1674-1718) The Work of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes. Published in London in 1709 by Jacob Tonson (1655–1736), this second edition holds an important place within Shakespearean publication history. The Work of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes is recognized as the first octavo edition, the first illustrated edition, the first critically edited edition, and the first to present a biography of the poet.

Volume five contains Shakespeare’s renowned tragedies beginning with everyone’s favorite young Italian lovers, Romeo and Juliet. Following Romeo and Juliet is Timon of Athens, Julius Caesar, Macbeth, Hamlet Prince of Denmark, King Lear, and Othello. A full-page engraving by the French artist and book illustrator François Boitard (1670-1715) precedes each play. The illustrations were engraved by prolific English engraver Elisha Kirkall (c.1682–1742) who had previously worked with Rowe on his translation of Lucan's Pharsalia. Boitard’s illustrations often place readers at the pinnacle of the plays depicting high drama in his classic Baroque style.

In addition to Rowe’s editorial decisions to divide the plays into scenes and include notes on the entrances and exits of the players, he also normalised the spelling of names and included a dramatis personae preceding each play. The only chronicled critique of Rowe’s momentous editorial endeavor is his choice in basing his text on the corrupt Fourth Folio.

View more volumes of The Works of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes here.

View more Shakespeare Weekend posts.

-Jenna, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#shakespeare weekend#nicholas rowe#the work of mr. william shakespear#jacob tonson#francois boitard#elisha kirkall#romeo and juliet#timon of athens#julius caesar#macbeth#hamlet#king lear#othello

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

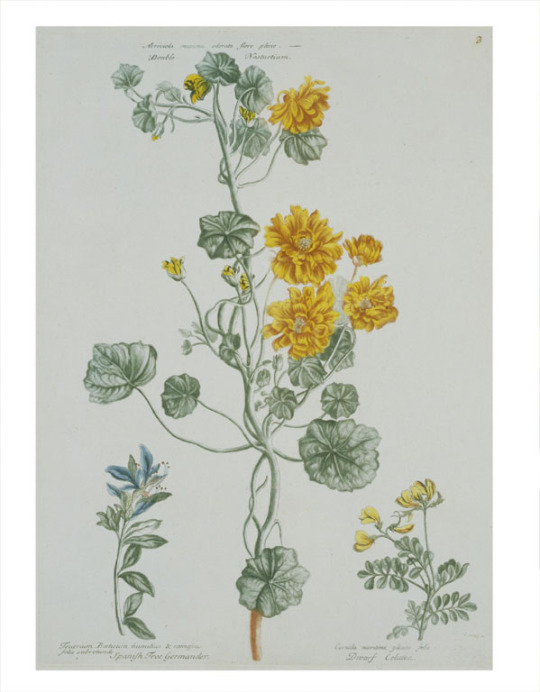

Double nasturtium, Spanish tree germander, dwarf colutea (1730).

Mezzotint taken from ‘Catalogus Plantarum' by Elisha Kirkall after Jacob van Huysum.

Image and text information courtesy V&A.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2017. All Rights Reserved

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Double nasturtium, Spanish tree germander and dwarf colutea (1730) by Jacob van Huysum.

Colour mezzotint by Elisha Kirkall.

Image and text information courtesy V & A.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2017. All Rights Reserved

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Saint Paul Preaching in Athens, Elisha Kirkall, c. 1730, Harvard Art Museums: Prints

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Horace M. Swope, Class of 1905

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/255208

0 notes

Photo

Gaspard Gevaerts (?), Elisha Kirkall, 18th century, Harvard Art Museums: Prints

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Paul J. Sachs

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/256122

0 notes

Photo

Long-Coned Cornish Fir, Balm of Gilead Fir.

Taken from A Society of Gardeners, "Catalogus Plantarum"..., London, 1730).

After Jacobus van Huysum (Dutch, active in England, 1687/89–1740), Elisha Kirkall (English, about 1682–1742).

Image and text courtesy MFA Boston.

110 notes

·

View notes