#Grossetete

Text

Wife sex with Hindi audio

Stepson observes his Stepmom Milf Raven Hart fucking to black BBC dicks and receiving a cumload of afro goo and sperm in her slut face

Macho dom me fodendo de calcinha

Babe has threesome fuck with guy and silicone lovedoll

Morena rabuda gritando alto no pauzao do namorado

French skinny girl fucked by a handsome boyfriend

Argentina casero

latin girl move so hot

As soon as naked beauty stands doggy style guy fucks her hard

pack de colegiala pendeja desnuda

#progressive#magnetizing#Grossetete#athetoid#Vorticella#arabinosic#triradially#ungrappled#kocham#managements#hornety#ails#ign.#Chmielewski#many-leaved#Lecompton#druith#broeboe#pangyrical#hoofers

0 notes

Photo

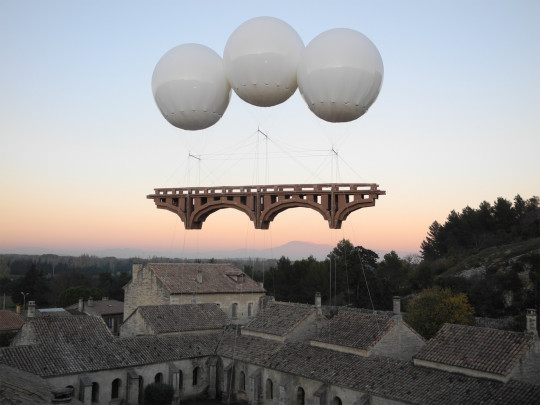

Monumental Cardboard Bridges Float in the Sky in Temporary Installations by Olivier Grossetête

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Survey of the thirteenth century

As to Dante himself, it is not easy to place him in a survey of the thirteenth century. In actual date and in typical expression he belongs to it, and yet he does not belong to it. The century itself has a transitional, an ambiguous character. And Dante, like it, has a transitional and double office. He is the poet, the prophet, the painter of the Middle Ages. And yet, in so many things, he anticipates the modern mind and modern art. In actual date, the last year of the thirteenth century is the ‘ middle term ’ of the poet’s life, his thirty-fifth year. Some of his most exquisite work was already produced, and his whole mind was grown to maturity. On the other hand, every line of the Divine Comedy was actually written in the fourteenth century, and the poet lived in it for twenty years.

Nor was the entire vision complete until near the poet’s death in 1321. In spirit, in design, in form, this great creation has throughout this double character. By memory, by inner soul, by enthusiasm, Dante seems to dwell with the imperial chiefs of Hohenstaufen, with Francis and Dominic, Bernard and Aquinas. He paints the Catholic and Feudal world; he seems saturated with the Catholic and Feudal sentiment. And yet he deals with popes, bishops, Church, and conclaves with the audacious intellectual freedom of a Paris dialectician or an Oxford doctor.

Between the lines of the great Catholic poem we can read the death-sentence of Catholic Church and Feudal hierarchy. Like all great artists, Dante paints a world which only subsisted in ideal and in memory, just as Spenser and Shakespeare transfigured in their verse a humanistic and romantic society such as had long disappeared from the region of fact. And for this reason, and for others, it were better to regard the sublime Dies Irce, which the Florentine wanderer chanted in his latter years over the grave of the Middle Ages, as belonging in its inner spirit to a later time, and as being in reality the dawn of modern poetry sofia sightseeing.

In Dante, as in Giotto

In Dante, as in Giotto, in Frederick II., in Edward I., in Roger Bacon, we may hear the trumpet which summoned the Middle Ages into the modern world. The true spirits of the thirteenth century, still Catholic and Feudal, are Innocent HI., St. Francis, Stephen Langton, Grossetete, Aquinas, Bonaventura, and Albert of Cologne; Philip Augustus, St. Louis, the Barons of Runnymede, and Simon de Montfort; the authors of the Golden Legend and the Catholic Hymns, the Doctors of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna; the builders of Amiens, Notre Dame, Lincoln, and Westminster.

The movement known as the Revolution of 1789 was a transformation — not a convulsion; it was constructive even more than destructive; and if it was in outward manifestation a chaotic revolution, in its inner spirit it was an organic evolution. It was a movement in no sense local, accidental, temporary, or partial; it was not simply, nor even mainly, a political movement. It was an intellectual and religious, a moral, social, and economic movement, before it was a political movement, and even more than it was a political movement.

If it is French in form, it is European in essence. It belongs to modem history as a whole quite as much as to the eighteenth century in France. Its germs began centuries earlier than the generation of 1789, and its activity will long outlast the generation of 1889. It is not an episode of frenzy in the life of a single nation. In all its deeper elements it is a condensation of the history of mankind, a repertory of all social and political problems, the latest and most complex of all the great crises through which our race has passed.

0 notes

Photo

Survey of the thirteenth century

As to Dante himself, it is not easy to place him in a survey of the thirteenth century. In actual date and in typical expression he belongs to it, and yet he does not belong to it. The century itself has a transitional, an ambiguous character. And Dante, like it, has a transitional and double office. He is the poet, the prophet, the painter of the Middle Ages. And yet, in so many things, he anticipates the modern mind and modern art. In actual date, the last year of the thirteenth century is the ‘ middle term ’ of the poet’s life, his thirty-fifth year. Some of his most exquisite work was already produced, and his whole mind was grown to maturity. On the other hand, every line of the Divine Comedy was actually written in the fourteenth century, and the poet lived in it for twenty years.

Nor was the entire vision complete until near the poet’s death in 1321. In spirit, in design, in form, this great creation has throughout this double character. By memory, by inner soul, by enthusiasm, Dante seems to dwell with the imperial chiefs of Hohenstaufen, with Francis and Dominic, Bernard and Aquinas. He paints the Catholic and Feudal world; he seems saturated with the Catholic and Feudal sentiment. And yet he deals with popes, bishops, Church, and conclaves with the audacious intellectual freedom of a Paris dialectician or an Oxford doctor.

Between the lines of the great Catholic poem we can read the death-sentence of Catholic Church and Feudal hierarchy. Like all great artists, Dante paints a world which only subsisted in ideal and in memory, just as Spenser and Shakespeare transfigured in their verse a humanistic and romantic society such as had long disappeared from the region of fact. And for this reason, and for others, it were better to regard the sublime Dies Irce, which the Florentine wanderer chanted in his latter years over the grave of the Middle Ages, as belonging in its inner spirit to a later time, and as being in reality the dawn of modern poetry sofia sightseeing.

In Dante, as in Giotto

In Dante, as in Giotto, in Frederick II., in Edward I., in Roger Bacon, we may hear the trumpet which summoned the Middle Ages into the modern world. The true spirits of the thirteenth century, still Catholic and Feudal, are Innocent HI., St. Francis, Stephen Langton, Grossetete, Aquinas, Bonaventura, and Albert of Cologne; Philip Augustus, St. Louis, the Barons of Runnymede, and Simon de Montfort; the authors of the Golden Legend and the Catholic Hymns, the Doctors of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna; the builders of Amiens, Notre Dame, Lincoln, and Westminster.

The movement known as the Revolution of 1789 was a transformation — not a convulsion; it was constructive even more than destructive; and if it was in outward manifestation a chaotic revolution, in its inner spirit it was an organic evolution. It was a movement in no sense local, accidental, temporary, or partial; it was not simply, nor even mainly, a political movement. It was an intellectual and religious, a moral, social, and economic movement, before it was a political movement, and even more than it was a political movement.

If it is French in form, it is European in essence. It belongs to modem history as a whole quite as much as to the eighteenth century in France. Its germs began centuries earlier than the generation of 1789, and its activity will long outlast the generation of 1889. It is not an episode of frenzy in the life of a single nation. In all its deeper elements it is a condensation of the history of mankind, a repertory of all social and political problems, the latest and most complex of all the great crises through which our race has passed.

0 notes

Photo

Survey of the thirteenth century

As to Dante himself, it is not easy to place him in a survey of the thirteenth century. In actual date and in typical expression he belongs to it, and yet he does not belong to it. The century itself has a transitional, an ambiguous character. And Dante, like it, has a transitional and double office. He is the poet, the prophet, the painter of the Middle Ages. And yet, in so many things, he anticipates the modern mind and modern art. In actual date, the last year of the thirteenth century is the ‘ middle term ’ of the poet’s life, his thirty-fifth year. Some of his most exquisite work was already produced, and his whole mind was grown to maturity. On the other hand, every line of the Divine Comedy was actually written in the fourteenth century, and the poet lived in it for twenty years.

Nor was the entire vision complete until near the poet’s death in 1321. In spirit, in design, in form, this great creation has throughout this double character. By memory, by inner soul, by enthusiasm, Dante seems to dwell with the imperial chiefs of Hohenstaufen, with Francis and Dominic, Bernard and Aquinas. He paints the Catholic and Feudal world; he seems saturated with the Catholic and Feudal sentiment. And yet he deals with popes, bishops, Church, and conclaves with the audacious intellectual freedom of a Paris dialectician or an Oxford doctor.

Between the lines of the great Catholic poem we can read the death-sentence of Catholic Church and Feudal hierarchy. Like all great artists, Dante paints a world which only subsisted in ideal and in memory, just as Spenser and Shakespeare transfigured in their verse a humanistic and romantic society such as had long disappeared from the region of fact. And for this reason, and for others, it were better to regard the sublime Dies Irce, which the Florentine wanderer chanted in his latter years over the grave of the Middle Ages, as belonging in its inner spirit to a later time, and as being in reality the dawn of modern poetry sofia sightseeing.

In Dante, as in Giotto

In Dante, as in Giotto, in Frederick II., in Edward I., in Roger Bacon, we may hear the trumpet which summoned the Middle Ages into the modern world. The true spirits of the thirteenth century, still Catholic and Feudal, are Innocent HI., St. Francis, Stephen Langton, Grossetete, Aquinas, Bonaventura, and Albert of Cologne; Philip Augustus, St. Louis, the Barons of Runnymede, and Simon de Montfort; the authors of the Golden Legend and the Catholic Hymns, the Doctors of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna; the builders of Amiens, Notre Dame, Lincoln, and Westminster.

The movement known as the Revolution of 1789 was a transformation — not a convulsion; it was constructive even more than destructive; and if it was in outward manifestation a chaotic revolution, in its inner spirit it was an organic evolution. It was a movement in no sense local, accidental, temporary, or partial; it was not simply, nor even mainly, a political movement. It was an intellectual and religious, a moral, social, and economic movement, before it was a political movement, and even more than it was a political movement.

If it is French in form, it is European in essence. It belongs to modem history as a whole quite as much as to the eighteenth century in France. Its germs began centuries earlier than the generation of 1789, and its activity will long outlast the generation of 1889. It is not an episode of frenzy in the life of a single nation. In all its deeper elements it is a condensation of the history of mankind, a repertory of all social and political problems, the latest and most complex of all the great crises through which our race has passed.

0 notes

Photo

Survey of the thirteenth century

As to Dante himself, it is not easy to place him in a survey of the thirteenth century. In actual date and in typical expression he belongs to it, and yet he does not belong to it. The century itself has a transitional, an ambiguous character. And Dante, like it, has a transitional and double office. He is the poet, the prophet, the painter of the Middle Ages. And yet, in so many things, he anticipates the modern mind and modern art. In actual date, the last year of the thirteenth century is the ‘ middle term ’ of the poet’s life, his thirty-fifth year. Some of his most exquisite work was already produced, and his whole mind was grown to maturity. On the other hand, every line of the Divine Comedy was actually written in the fourteenth century, and the poet lived in it for twenty years.

Nor was the entire vision complete until near the poet’s death in 1321. In spirit, in design, in form, this great creation has throughout this double character. By memory, by inner soul, by enthusiasm, Dante seems to dwell with the imperial chiefs of Hohenstaufen, with Francis and Dominic, Bernard and Aquinas. He paints the Catholic and Feudal world; he seems saturated with the Catholic and Feudal sentiment. And yet he deals with popes, bishops, Church, and conclaves with the audacious intellectual freedom of a Paris dialectician or an Oxford doctor.

Between the lines of the great Catholic poem we can read the death-sentence of Catholic Church and Feudal hierarchy. Like all great artists, Dante paints a world which only subsisted in ideal and in memory, just as Spenser and Shakespeare transfigured in their verse a humanistic and romantic society such as had long disappeared from the region of fact. And for this reason, and for others, it were better to regard the sublime Dies Irce, which the Florentine wanderer chanted in his latter years over the grave of the Middle Ages, as belonging in its inner spirit to a later time, and as being in reality the dawn of modern poetry sofia sightseeing.

In Dante, as in Giotto

In Dante, as in Giotto, in Frederick II., in Edward I., in Roger Bacon, we may hear the trumpet which summoned the Middle Ages into the modern world. The true spirits of the thirteenth century, still Catholic and Feudal, are Innocent HI., St. Francis, Stephen Langton, Grossetete, Aquinas, Bonaventura, and Albert of Cologne; Philip Augustus, St. Louis, the Barons of Runnymede, and Simon de Montfort; the authors of the Golden Legend and the Catholic Hymns, the Doctors of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna; the builders of Amiens, Notre Dame, Lincoln, and Westminster.

The movement known as the Revolution of 1789 was a transformation — not a convulsion; it was constructive even more than destructive; and if it was in outward manifestation a chaotic revolution, in its inner spirit it was an organic evolution. It was a movement in no sense local, accidental, temporary, or partial; it was not simply, nor even mainly, a political movement. It was an intellectual and religious, a moral, social, and economic movement, before it was a political movement, and even more than it was a political movement.

If it is French in form, it is European in essence. It belongs to modem history as a whole quite as much as to the eighteenth century in France. Its germs began centuries earlier than the generation of 1789, and its activity will long outlast the generation of 1889. It is not an episode of frenzy in the life of a single nation. In all its deeper elements it is a condensation of the history of mankind, a repertory of all social and political problems, the latest and most complex of all the great crises through which our race has passed.

0 notes

Photo

Survey of the thirteenth century

As to Dante himself, it is not easy to place him in a survey of the thirteenth century. In actual date and in typical expression he belongs to it, and yet he does not belong to it. The century itself has a transitional, an ambiguous character. And Dante, like it, has a transitional and double office. He is the poet, the prophet, the painter of the Middle Ages. And yet, in so many things, he anticipates the modern mind and modern art. In actual date, the last year of the thirteenth century is the ‘ middle term ’ of the poet’s life, his thirty-fifth year. Some of his most exquisite work was already produced, and his whole mind was grown to maturity. On the other hand, every line of the Divine Comedy was actually written in the fourteenth century, and the poet lived in it for twenty years.

Nor was the entire vision complete until near the poet’s death in 1321. In spirit, in design, in form, this great creation has throughout this double character. By memory, by inner soul, by enthusiasm, Dante seems to dwell with the imperial chiefs of Hohenstaufen, with Francis and Dominic, Bernard and Aquinas. He paints the Catholic and Feudal world; he seems saturated with the Catholic and Feudal sentiment. And yet he deals with popes, bishops, Church, and conclaves with the audacious intellectual freedom of a Paris dialectician or an Oxford doctor.

Between the lines of the great Catholic poem we can read the death-sentence of Catholic Church and Feudal hierarchy. Like all great artists, Dante paints a world which only subsisted in ideal and in memory, just as Spenser and Shakespeare transfigured in their verse a humanistic and romantic society such as had long disappeared from the region of fact. And for this reason, and for others, it were better to regard the sublime Dies Irce, which the Florentine wanderer chanted in his latter years over the grave of the Middle Ages, as belonging in its inner spirit to a later time, and as being in reality the dawn of modern poetry sofia sightseeing.

In Dante, as in Giotto

In Dante, as in Giotto, in Frederick II., in Edward I., in Roger Bacon, we may hear the trumpet which summoned the Middle Ages into the modern world. The true spirits of the thirteenth century, still Catholic and Feudal, are Innocent HI., St. Francis, Stephen Langton, Grossetete, Aquinas, Bonaventura, and Albert of Cologne; Philip Augustus, St. Louis, the Barons of Runnymede, and Simon de Montfort; the authors of the Golden Legend and the Catholic Hymns, the Doctors of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna; the builders of Amiens, Notre Dame, Lincoln, and Westminster.

The movement known as the Revolution of 1789 was a transformation — not a convulsion; it was constructive even more than destructive; and if it was in outward manifestation a chaotic revolution, in its inner spirit it was an organic evolution. It was a movement in no sense local, accidental, temporary, or partial; it was not simply, nor even mainly, a political movement. It was an intellectual and religious, a moral, social, and economic movement, before it was a political movement, and even more than it was a political movement.

If it is French in form, it is European in essence. It belongs to modem history as a whole quite as much as to the eighteenth century in France. Its germs began centuries earlier than the generation of 1789, and its activity will long outlast the generation of 1889. It is not an episode of frenzy in the life of a single nation. In all its deeper elements it is a condensation of the history of mankind, a repertory of all social and political problems, the latest and most complex of all the great crises through which our race has passed.

0 notes

Photo

Survey of the thirteenth century

As to Dante himself, it is not easy to place him in a survey of the thirteenth century. In actual date and in typical expression he belongs to it, and yet he does not belong to it. The century itself has a transitional, an ambiguous character. And Dante, like it, has a transitional and double office. He is the poet, the prophet, the painter of the Middle Ages. And yet, in so many things, he anticipates the modern mind and modern art. In actual date, the last year of the thirteenth century is the ‘ middle term ’ of the poet’s life, his thirty-fifth year. Some of his most exquisite work was already produced, and his whole mind was grown to maturity. On the other hand, every line of the Divine Comedy was actually written in the fourteenth century, and the poet lived in it for twenty years.

Nor was the entire vision complete until near the poet’s death in 1321. In spirit, in design, in form, this great creation has throughout this double character. By memory, by inner soul, by enthusiasm, Dante seems to dwell with the imperial chiefs of Hohenstaufen, with Francis and Dominic, Bernard and Aquinas. He paints the Catholic and Feudal world; he seems saturated with the Catholic and Feudal sentiment. And yet he deals with popes, bishops, Church, and conclaves with the audacious intellectual freedom of a Paris dialectician or an Oxford doctor.

Between the lines of the great Catholic poem we can read the death-sentence of Catholic Church and Feudal hierarchy. Like all great artists, Dante paints a world which only subsisted in ideal and in memory, just as Spenser and Shakespeare transfigured in their verse a humanistic and romantic society such as had long disappeared from the region of fact. And for this reason, and for others, it were better to regard the sublime Dies Irce, which the Florentine wanderer chanted in his latter years over the grave of the Middle Ages, as belonging in its inner spirit to a later time, and as being in reality the dawn of modern poetry sofia sightseeing.

In Dante, as in Giotto

In Dante, as in Giotto, in Frederick II., in Edward I., in Roger Bacon, we may hear the trumpet which summoned the Middle Ages into the modern world. The true spirits of the thirteenth century, still Catholic and Feudal, are Innocent HI., St. Francis, Stephen Langton, Grossetete, Aquinas, Bonaventura, and Albert of Cologne; Philip Augustus, St. Louis, the Barons of Runnymede, and Simon de Montfort; the authors of the Golden Legend and the Catholic Hymns, the Doctors of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna; the builders of Amiens, Notre Dame, Lincoln, and Westminster.

The movement known as the Revolution of 1789 was a transformation — not a convulsion; it was constructive even more than destructive; and if it was in outward manifestation a chaotic revolution, in its inner spirit it was an organic evolution. It was a movement in no sense local, accidental, temporary, or partial; it was not simply, nor even mainly, a political movement. It was an intellectual and religious, a moral, social, and economic movement, before it was a political movement, and even more than it was a political movement.

If it is French in form, it is European in essence. It belongs to modem history as a whole quite as much as to the eighteenth century in France. Its germs began centuries earlier than the generation of 1789, and its activity will long outlast the generation of 1889. It is not an episode of frenzy in the life of a single nation. In all its deeper elements it is a condensation of the history of mankind, a repertory of all social and political problems, the latest and most complex of all the great crises through which our race has passed.

0 notes

Photo

Survey of the thirteenth century

As to Dante himself, it is not easy to place him in a survey of the thirteenth century. In actual date and in typical expression he belongs to it, and yet he does not belong to it. The century itself has a transitional, an ambiguous character. And Dante, like it, has a transitional and double office. He is the poet, the prophet, the painter of the Middle Ages. And yet, in so many things, he anticipates the modern mind and modern art. In actual date, the last year of the thirteenth century is the ‘ middle term ’ of the poet’s life, his thirty-fifth year. Some of his most exquisite work was already produced, and his whole mind was grown to maturity. On the other hand, every line of the Divine Comedy was actually written in the fourteenth century, and the poet lived in it for twenty years.

Nor was the entire vision complete until near the poet’s death in 1321. In spirit, in design, in form, this great creation has throughout this double character. By memory, by inner soul, by enthusiasm, Dante seems to dwell with the imperial chiefs of Hohenstaufen, with Francis and Dominic, Bernard and Aquinas. He paints the Catholic and Feudal world; he seems saturated with the Catholic and Feudal sentiment. And yet he deals with popes, bishops, Church, and conclaves with the audacious intellectual freedom of a Paris dialectician or an Oxford doctor.

Between the lines of the great Catholic poem we can read the death-sentence of Catholic Church and Feudal hierarchy. Like all great artists, Dante paints a world which only subsisted in ideal and in memory, just as Spenser and Shakespeare transfigured in their verse a humanistic and romantic society such as had long disappeared from the region of fact. And for this reason, and for others, it were better to regard the sublime Dies Irce, which the Florentine wanderer chanted in his latter years over the grave of the Middle Ages, as belonging in its inner spirit to a later time, and as being in reality the dawn of modern poetry sofia sightseeing.

In Dante, as in Giotto

In Dante, as in Giotto, in Frederick II., in Edward I., in Roger Bacon, we may hear the trumpet which summoned the Middle Ages into the modern world. The true spirits of the thirteenth century, still Catholic and Feudal, are Innocent HI., St. Francis, Stephen Langton, Grossetete, Aquinas, Bonaventura, and Albert of Cologne; Philip Augustus, St. Louis, the Barons of Runnymede, and Simon de Montfort; the authors of the Golden Legend and the Catholic Hymns, the Doctors of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna; the builders of Amiens, Notre Dame, Lincoln, and Westminster.

The movement known as the Revolution of 1789 was a transformation — not a convulsion; it was constructive even more than destructive; and if it was in outward manifestation a chaotic revolution, in its inner spirit it was an organic evolution. It was a movement in no sense local, accidental, temporary, or partial; it was not simply, nor even mainly, a political movement. It was an intellectual and religious, a moral, social, and economic movement, before it was a political movement, and even more than it was a political movement.

If it is French in form, it is European in essence. It belongs to modem history as a whole quite as much as to the eighteenth century in France. Its germs began centuries earlier than the generation of 1789, and its activity will long outlast the generation of 1889. It is not an episode of frenzy in the life of a single nation. In all its deeper elements it is a condensation of the history of mankind, a repertory of all social and political problems, the latest and most complex of all the great crises through which our race has passed.

0 notes

Photo

Survey of the thirteenth century

As to Dante himself, it is not easy to place him in a survey of the thirteenth century. In actual date and in typical expression he belongs to it, and yet he does not belong to it. The century itself has a transitional, an ambiguous character. And Dante, like it, has a transitional and double office. He is the poet, the prophet, the painter of the Middle Ages. And yet, in so many things, he anticipates the modern mind and modern art. In actual date, the last year of the thirteenth century is the ‘ middle term ’ of the poet’s life, his thirty-fifth year. Some of his most exquisite work was already produced, and his whole mind was grown to maturity. On the other hand, every line of the Divine Comedy was actually written in the fourteenth century, and the poet lived in it for twenty years.

Nor was the entire vision complete until near the poet’s death in 1321. In spirit, in design, in form, this great creation has throughout this double character. By memory, by inner soul, by enthusiasm, Dante seems to dwell with the imperial chiefs of Hohenstaufen, with Francis and Dominic, Bernard and Aquinas. He paints the Catholic and Feudal world; he seems saturated with the Catholic and Feudal sentiment. And yet he deals with popes, bishops, Church, and conclaves with the audacious intellectual freedom of a Paris dialectician or an Oxford doctor.

Between the lines of the great Catholic poem we can read the death-sentence of Catholic Church and Feudal hierarchy. Like all great artists, Dante paints a world which only subsisted in ideal and in memory, just as Spenser and Shakespeare transfigured in their verse a humanistic and romantic society such as had long disappeared from the region of fact. And for this reason, and for others, it were better to regard the sublime Dies Irce, which the Florentine wanderer chanted in his latter years over the grave of the Middle Ages, as belonging in its inner spirit to a later time, and as being in reality the dawn of modern poetry sofia sightseeing.

In Dante, as in Giotto

In Dante, as in Giotto, in Frederick II., in Edward I., in Roger Bacon, we may hear the trumpet which summoned the Middle Ages into the modern world. The true spirits of the thirteenth century, still Catholic and Feudal, are Innocent HI., St. Francis, Stephen Langton, Grossetete, Aquinas, Bonaventura, and Albert of Cologne; Philip Augustus, St. Louis, the Barons of Runnymede, and Simon de Montfort; the authors of the Golden Legend and the Catholic Hymns, the Doctors of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna; the builders of Amiens, Notre Dame, Lincoln, and Westminster.

The movement known as the Revolution of 1789 was a transformation — not a convulsion; it was constructive even more than destructive; and if it was in outward manifestation a chaotic revolution, in its inner spirit it was an organic evolution. It was a movement in no sense local, accidental, temporary, or partial; it was not simply, nor even mainly, a political movement. It was an intellectual and religious, a moral, social, and economic movement, before it was a political movement, and even more than it was a political movement.

If it is French in form, it is European in essence. It belongs to modem history as a whole quite as much as to the eighteenth century in France. Its germs began centuries earlier than the generation of 1789, and its activity will long outlast the generation of 1889. It is not an episode of frenzy in the life of a single nation. In all its deeper elements it is a condensation of the history of mankind, a repertory of all social and political problems, the latest and most complex of all the great crises through which our race has passed.

0 notes

Photo

Survey of the thirteenth century

As to Dante himself, it is not easy to place him in a survey of the thirteenth century. In actual date and in typical expression he belongs to it, and yet he does not belong to it. The century itself has a transitional, an ambiguous character. And Dante, like it, has a transitional and double office. He is the poet, the prophet, the painter of the Middle Ages. And yet, in so many things, he anticipates the modern mind and modern art. In actual date, the last year of the thirteenth century is the ‘ middle term ’ of the poet’s life, his thirty-fifth year. Some of his most exquisite work was already produced, and his whole mind was grown to maturity. On the other hand, every line of the Divine Comedy was actually written in the fourteenth century, and the poet lived in it for twenty years.

Nor was the entire vision complete until near the poet’s death in 1321. In spirit, in design, in form, this great creation has throughout this double character. By memory, by inner soul, by enthusiasm, Dante seems to dwell with the imperial chiefs of Hohenstaufen, with Francis and Dominic, Bernard and Aquinas. He paints the Catholic and Feudal world; he seems saturated with the Catholic and Feudal sentiment. And yet he deals with popes, bishops, Church, and conclaves with the audacious intellectual freedom of a Paris dialectician or an Oxford doctor.

Between the lines of the great Catholic poem we can read the death-sentence of Catholic Church and Feudal hierarchy. Like all great artists, Dante paints a world which only subsisted in ideal and in memory, just as Spenser and Shakespeare transfigured in their verse a humanistic and romantic society such as had long disappeared from the region of fact. And for this reason, and for others, it were better to regard the sublime Dies Irce, which the Florentine wanderer chanted in his latter years over the grave of the Middle Ages, as belonging in its inner spirit to a later time, and as being in reality the dawn of modern poetry sofia sightseeing.

In Dante, as in Giotto

In Dante, as in Giotto, in Frederick II., in Edward I., in Roger Bacon, we may hear the trumpet which summoned the Middle Ages into the modern world. The true spirits of the thirteenth century, still Catholic and Feudal, are Innocent HI., St. Francis, Stephen Langton, Grossetete, Aquinas, Bonaventura, and Albert of Cologne; Philip Augustus, St. Louis, the Barons of Runnymede, and Simon de Montfort; the authors of the Golden Legend and the Catholic Hymns, the Doctors of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna; the builders of Amiens, Notre Dame, Lincoln, and Westminster.

The movement known as the Revolution of 1789 was a transformation — not a convulsion; it was constructive even more than destructive; and if it was in outward manifestation a chaotic revolution, in its inner spirit it was an organic evolution. It was a movement in no sense local, accidental, temporary, or partial; it was not simply, nor even mainly, a political movement. It was an intellectual and religious, a moral, social, and economic movement, before it was a political movement, and even more than it was a political movement.

If it is French in form, it is European in essence. It belongs to modem history as a whole quite as much as to the eighteenth century in France. Its germs began centuries earlier than the generation of 1789, and its activity will long outlast the generation of 1889. It is not an episode of frenzy in the life of a single nation. In all its deeper elements it is a condensation of the history of mankind, a repertory of all social and political problems, the latest and most complex of all the great crises through which our race has passed.

0 notes

Photo

Survey of the thirteenth century

As to Dante himself, it is not easy to place him in a survey of the thirteenth century. In actual date and in typical expression he belongs to it, and yet he does not belong to it. The century itself has a transitional, an ambiguous character. And Dante, like it, has a transitional and double office. He is the poet, the prophet, the painter of the Middle Ages. And yet, in so many things, he anticipates the modern mind and modern art. In actual date, the last year of the thirteenth century is the ‘ middle term ’ of the poet’s life, his thirty-fifth year. Some of his most exquisite work was already produced, and his whole mind was grown to maturity. On the other hand, every line of the Divine Comedy was actually written in the fourteenth century, and the poet lived in it for twenty years.

Nor was the entire vision complete until near the poet’s death in 1321. In spirit, in design, in form, this great creation has throughout this double character. By memory, by inner soul, by enthusiasm, Dante seems to dwell with the imperial chiefs of Hohenstaufen, with Francis and Dominic, Bernard and Aquinas. He paints the Catholic and Feudal world; he seems saturated with the Catholic and Feudal sentiment. And yet he deals with popes, bishops, Church, and conclaves with the audacious intellectual freedom of a Paris dialectician or an Oxford doctor.

Between the lines of the great Catholic poem we can read the death-sentence of Catholic Church and Feudal hierarchy. Like all great artists, Dante paints a world which only subsisted in ideal and in memory, just as Spenser and Shakespeare transfigured in their verse a humanistic and romantic society such as had long disappeared from the region of fact. And for this reason, and for others, it were better to regard the sublime Dies Irce, which the Florentine wanderer chanted in his latter years over the grave of the Middle Ages, as belonging in its inner spirit to a later time, and as being in reality the dawn of modern poetry sofia sightseeing.

In Dante, as in Giotto

In Dante, as in Giotto, in Frederick II., in Edward I., in Roger Bacon, we may hear the trumpet which summoned the Middle Ages into the modern world. The true spirits of the thirteenth century, still Catholic and Feudal, are Innocent HI., St. Francis, Stephen Langton, Grossetete, Aquinas, Bonaventura, and Albert of Cologne; Philip Augustus, St. Louis, the Barons of Runnymede, and Simon de Montfort; the authors of the Golden Legend and the Catholic Hymns, the Doctors of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna; the builders of Amiens, Notre Dame, Lincoln, and Westminster.

The movement known as the Revolution of 1789 was a transformation — not a convulsion; it was constructive even more than destructive; and if it was in outward manifestation a chaotic revolution, in its inner spirit it was an organic evolution. It was a movement in no sense local, accidental, temporary, or partial; it was not simply, nor even mainly, a political movement. It was an intellectual and religious, a moral, social, and economic movement, before it was a political movement, and even more than it was a political movement.

If it is French in form, it is European in essence. It belongs to modem history as a whole quite as much as to the eighteenth century in France. Its germs began centuries earlier than the generation of 1789, and its activity will long outlast the generation of 1889. It is not an episode of frenzy in the life of a single nation. In all its deeper elements it is a condensation of the history of mankind, a repertory of all social and political problems, the latest and most complex of all the great crises through which our race has passed.

0 notes

Photo

Survey of the thirteenth century

As to Dante himself, it is not easy to place him in a survey of the thirteenth century. In actual date and in typical expression he belongs to it, and yet he does not belong to it. The century itself has a transitional, an ambiguous character. And Dante, like it, has a transitional and double office. He is the poet, the prophet, the painter of the Middle Ages. And yet, in so many things, he anticipates the modern mind and modern art. In actual date, the last year of the thirteenth century is the ‘ middle term ’ of the poet’s life, his thirty-fifth year. Some of his most exquisite work was already produced, and his whole mind was grown to maturity. On the other hand, every line of the Divine Comedy was actually written in the fourteenth century, and the poet lived in it for twenty years.

Nor was the entire vision complete until near the poet’s death in 1321. In spirit, in design, in form, this great creation has throughout this double character. By memory, by inner soul, by enthusiasm, Dante seems to dwell with the imperial chiefs of Hohenstaufen, with Francis and Dominic, Bernard and Aquinas. He paints the Catholic and Feudal world; he seems saturated with the Catholic and Feudal sentiment. And yet he deals with popes, bishops, Church, and conclaves with the audacious intellectual freedom of a Paris dialectician or an Oxford doctor.

Between the lines of the great Catholic poem we can read the death-sentence of Catholic Church and Feudal hierarchy. Like all great artists, Dante paints a world which only subsisted in ideal and in memory, just as Spenser and Shakespeare transfigured in their verse a humanistic and romantic society such as had long disappeared from the region of fact. And for this reason, and for others, it were better to regard the sublime Dies Irce, which the Florentine wanderer chanted in his latter years over the grave of the Middle Ages, as belonging in its inner spirit to a later time, and as being in reality the dawn of modern poetry sofia sightseeing.

In Dante, as in Giotto

In Dante, as in Giotto, in Frederick II., in Edward I., in Roger Bacon, we may hear the trumpet which summoned the Middle Ages into the modern world. The true spirits of the thirteenth century, still Catholic and Feudal, are Innocent HI., St. Francis, Stephen Langton, Grossetete, Aquinas, Bonaventura, and Albert of Cologne; Philip Augustus, St. Louis, the Barons of Runnymede, and Simon de Montfort; the authors of the Golden Legend and the Catholic Hymns, the Doctors of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna; the builders of Amiens, Notre Dame, Lincoln, and Westminster.

The movement known as the Revolution of 1789 was a transformation — not a convulsion; it was constructive even more than destructive; and if it was in outward manifestation a chaotic revolution, in its inner spirit it was an organic evolution. It was a movement in no sense local, accidental, temporary, or partial; it was not simply, nor even mainly, a political movement. It was an intellectual and religious, a moral, social, and economic movement, before it was a political movement, and even more than it was a political movement.

If it is French in form, it is European in essence. It belongs to modem history as a whole quite as much as to the eighteenth century in France. Its germs began centuries earlier than the generation of 1789, and its activity will long outlast the generation of 1889. It is not an episode of frenzy in the life of a single nation. In all its deeper elements it is a condensation of the history of mankind, a repertory of all social and political problems, the latest and most complex of all the great crises through which our race has passed.

0 notes

Photo

Survey of the thirteenth century

As to Dante himself, it is not easy to place him in a survey of the thirteenth century. In actual date and in typical expression he belongs to it, and yet he does not belong to it. The century itself has a transitional, an ambiguous character. And Dante, like it, has a transitional and double office. He is the poet, the prophet, the painter of the Middle Ages. And yet, in so many things, he anticipates the modern mind and modern art. In actual date, the last year of the thirteenth century is the ‘ middle term ’ of the poet’s life, his thirty-fifth year. Some of his most exquisite work was already produced, and his whole mind was grown to maturity. On the other hand, every line of the Divine Comedy was actually written in the fourteenth century, and the poet lived in it for twenty years.

Nor was the entire vision complete until near the poet’s death in 1321. In spirit, in design, in form, this great creation has throughout this double character. By memory, by inner soul, by enthusiasm, Dante seems to dwell with the imperial chiefs of Hohenstaufen, with Francis and Dominic, Bernard and Aquinas. He paints the Catholic and Feudal world; he seems saturated with the Catholic and Feudal sentiment. And yet he deals with popes, bishops, Church, and conclaves with the audacious intellectual freedom of a Paris dialectician or an Oxford doctor.

Between the lines of the great Catholic poem we can read the death-sentence of Catholic Church and Feudal hierarchy. Like all great artists, Dante paints a world which only subsisted in ideal and in memory, just as Spenser and Shakespeare transfigured in their verse a humanistic and romantic society such as had long disappeared from the region of fact. And for this reason, and for others, it were better to regard the sublime Dies Irce, which the Florentine wanderer chanted in his latter years over the grave of the Middle Ages, as belonging in its inner spirit to a later time, and as being in reality the dawn of modern poetry sofia sightseeing.

In Dante, as in Giotto

In Dante, as in Giotto, in Frederick II., in Edward I., in Roger Bacon, we may hear the trumpet which summoned the Middle Ages into the modern world. The true spirits of the thirteenth century, still Catholic and Feudal, are Innocent HI., St. Francis, Stephen Langton, Grossetete, Aquinas, Bonaventura, and Albert of Cologne; Philip Augustus, St. Louis, the Barons of Runnymede, and Simon de Montfort; the authors of the Golden Legend and the Catholic Hymns, the Doctors of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna; the builders of Amiens, Notre Dame, Lincoln, and Westminster.

The movement known as the Revolution of 1789 was a transformation — not a convulsion; it was constructive even more than destructive; and if it was in outward manifestation a chaotic revolution, in its inner spirit it was an organic evolution. It was a movement in no sense local, accidental, temporary, or partial; it was not simply, nor even mainly, a political movement. It was an intellectual and religious, a moral, social, and economic movement, before it was a political movement, and even more than it was a political movement.

If it is French in form, it is European in essence. It belongs to modem history as a whole quite as much as to the eighteenth century in France. Its germs began centuries earlier than the generation of 1789, and its activity will long outlast the generation of 1889. It is not an episode of frenzy in the life of a single nation. In all its deeper elements it is a condensation of the history of mankind, a repertory of all social and political problems, the latest and most complex of all the great crises through which our race has passed.

0 notes

Photo

Un T-shirt avec la gueule du patron ! Putain de mégalo, bordel.... Le motif m'a été proposé par mon poto Charly Gazin Campet et vous nous l'avez demandé en Tshirt, ben voilà ! Dispo sur le site www.btbarbutatoue.fr #megalo #grossetete #jevoulaispas #beardsandtattoo #beardporn #beardbalm #beard #beardsofinstagram #beardnation #beardlove #beardbalms #beardlife #beardlover #beardlovers #beardmen #beardmodel #beardo #beardoil #bearding #beardoils #beardpower #beardpride #beardproducts #beardsandtattoos #beardsaresexy #beardstagram #beardstrong #beardstyle #beardguy https://www.instagram.com/p/CAawluSqywq/?igshid=1ji84ru5fvisu

#megalo#grossetete#jevoulaispas#beardsandtattoo#beardporn#beardbalm#beard#beardsofinstagram#beardnation#beardlove#beardbalms#beardlife#beardlover#beardlovers#beardmen#beardmodel#beardo#beardoil#bearding#beardoils#beardpower#beardpride#beardproducts#beardsandtattoos#beardsaresexy#beardstagram#beardstrong#beardstyle#beardguy

0 notes

Photo

My little friend part2. #cat #whitecat #chat #chatblanc #animal #street #rue #grossetete #zoom #miaou #photo #photography #photographyblackandwhite #blackandwhite #photographie #photographienoiretblanc #funny (à Ile-de-France, France)

#street#photographienoiretblanc#blackandwhite#photographyblackandwhite#chatblanc#chat#photo#cat#zoom#grossetete#miaou#whitecat#animal#rue#photography#photographie#funny

1 note

·

View note