#anatolia verre

Text

Conlang Corner 12.04.2023

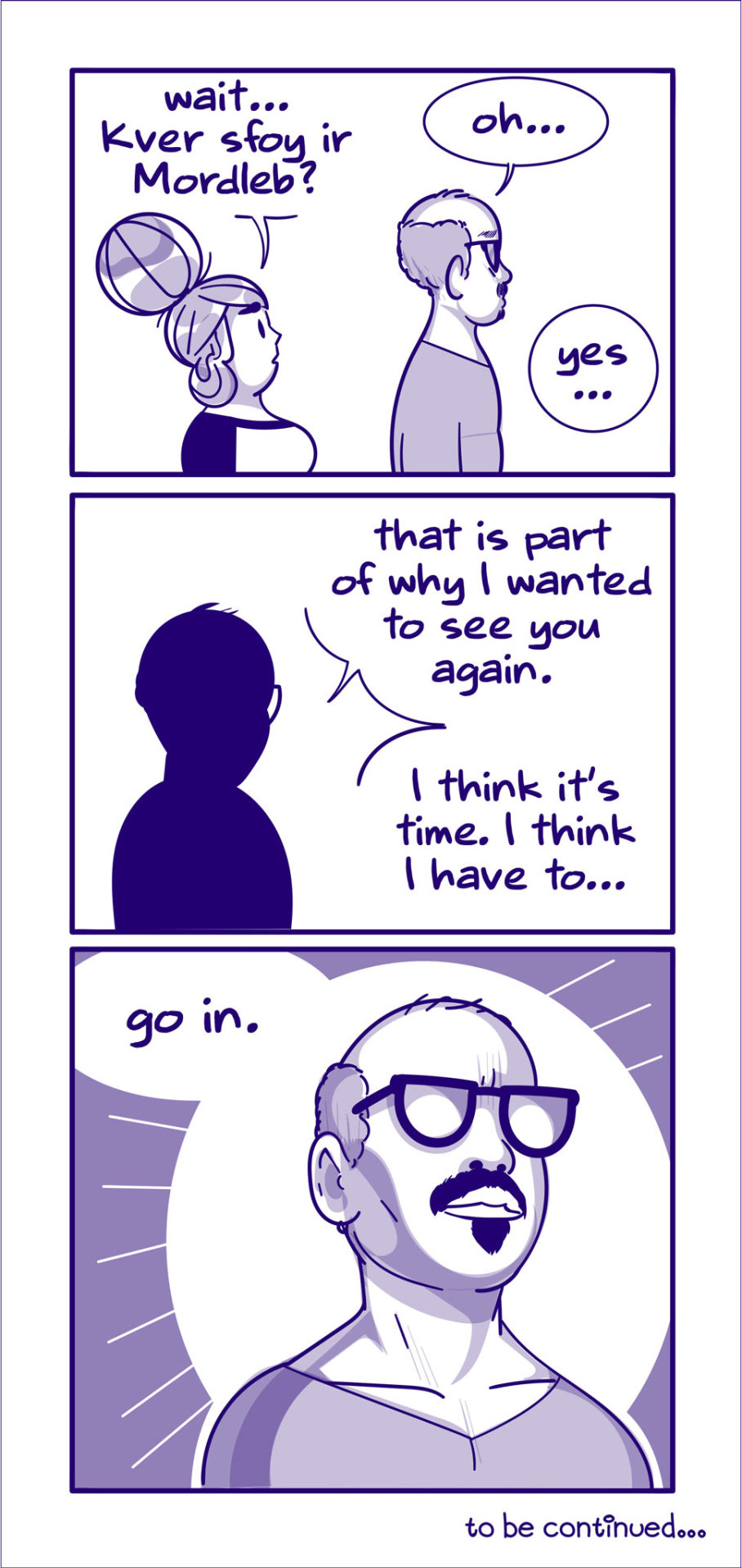

my first Conlang Corner! i am going to do my best to update every Monday. today we introduce you to Anatolia the Frame Skipper and her work with the cats of Farband.

166 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Also inhabited is Eryx, a lofty hill. It has an especially revered sanctuary

of Aphrodite; in past times it was filled with women hierodules whom many of Sicily and elsewhere dedicated according to a vow. But now,just like the settlement itself, the sanctuary is depopulated and the plethora of sacred bodies has left.

[...]

Chronology and terminology are very much at issue here. Strabo is discussing two different times – the to palaion and nuni – and, potentially, two different categories of sacred persons – the hierodules and the hiera sômata.

The various definitions of “hierodule” continued to function in the Roman period. […] The “women hierodules” discussed by Strabo in regards to Eryx seem to have a lot in common with their Corinthian counterparts – both are groups of exclusively women dedicated by men and women/Sicilians and others.

What about Strabo’s second term, the hiera sômata ? Who and what were these individuals populating the sanctuary of Eryx? From Strabo’s perspective, the term “sacred body” or “tou theou sômata ” (and as well the hieroi paides) could function as a synonym for “hierodule” especially in the more occidental regions of Anatolia. The epigraphic evidence from that region indicates that the hiera sômata worked for and came under the protection of the temples/deities. That “sacred bodies” worked for the temples is evident in a late third–early second-century bce building inscription from Didyma, where the temple architect and general manager give a list of expenditures, including an apologismos tôn gegenêmenôn dia tôn tou theou sômatôn, “an account of the works done by the bodies of the god.”

[...]

Evidently the sacred bodies were a group desirable to steal and most honorable to return. Strabo’s Erycine hiera sômata might then simply be seen as a synonym for his previously mentioned hierodules. The only odd aspect of this reference is the exclusive sex of the hierodules; in other instances both males and females were dedicated to the various deities, both as hierodules and as hierai/hieroi. That male hiera sômata existed is evident in the Didyma passage quoted above. Furthermore, there remains the question of whether or not Strabo’s Anatolian-based vocabulary (he was from Comana) adequately captures the realities of the Roman institution of so-called hierodouleia.Fortunately, in the case of Eryx we have additional, first-hand evidence that paints a fuller picture of these individuals sacred to Erycine Aphrodite in the Roman period from an earlier author – Cicero. In his Div. against Q. Caecilius, his Against Verres, and his Pro Aulus Cluentius Cicero sheds considerable light on the status and functions of the Venerii – the “slaves” of Erycine Venus. The passage in Caecilius is at once the most familiar and confusing, ultimately revealing the differences in sacred slavery as it pertained to the Roman west. According to Cicero (17.55–56),

There is a certain woman, Agonis of Lilybaeum, a liberta of Venus Erycina, who was quite well-to-do and wealthy before this man was quaestor. An admiral of Antonius abducted some musician-slaves from her in a violent, insulting manner, whom he said he wanted to use in the navy. Then, as is the custom of those of Venus (Venerorum) and those who have liberated

themselves from Venus, she invoked religion upon the commander in the name of Venus; she said that both she and hers belonged to Venus. When this was reported to quaestor Caecilius – that best and most just of men! – he commanded that Agonis be called to him. Immediately he appointed a commission [to see] “If it appeared that she had said that she and hers belonged to Venus.” The justices judged that it was surely so, nor was there indeed any doubt that she had said this. Then the cad [Caecilius] took possession of the woman’s goods, sentenced her into servitude to Venus, then sold her goods and pocketed the money. And so because Agonis wanted to retain a little property by the name of Venus and religiosity, she lost all her fortunes and liberty by the outrage of this cad! Verres later came to Lilybaeum, heard the matter, annulled the judgment, and bade the quaestor to count up and pay back all the money he got for selling Agonis’s goods.

The notion of divine protection is strongly reminiscent of what we have seen in the Hellenized east. Agonis, a former slave of Erycine Venus (liberta Veneris Erycinae) still claims that both she and her household are under the goddess’s protection. And well she might, for this protected status is also recognized and respected by the Sicilian government (for the most part), Cicero, and presumably his audience.It must be noted, though, that the evidence from Eryx actually presents two separate categories of what might be termed in Greek hierodules: those who are free (as with the manumissions seen above) and those who still belonged to the goddess – “omnium Veneriorum et eorum qui a Venere se liberaverunt,” “all those of Venus and of those who have liberated themselves from Venus.” In contrast to the eastern tradition, in the Roman tradition it would appear that sacred slaves were the equivalent of state-owned slaves, with the temple as opposed to the government having

ultimate authority over them. This is made clear in two additional passages from Cicero. In his Against Verres II, 38.86 Cicero, complaining about Verres’s abuses of power and nonstandard use of resources, mentions that when Verres was fleecing the people of Tissa:

The collector you sent to deal with them was Diognetus – a man of

Venus (Venerium). A new style of tax-farming – why are the public

slaves (servi publicani) here in Rome not taking up tax-farming as well

through this fellow?

Cicero equates the man of Venus – Diognetus – to a servus publicanus, a public slave. That those belonging to deities were not considered to be free as were their eastern cognates is also evident in the cult of another deity – Mars of Larinum. In his Defense of Cluentius Cicero discusses a political power-play in this town pertaining to the Martiales – “those of Mars” (15.43):

In Larinum there are certain men called Martiales, public ministers

(ministri publici) of Mars and consecrated to this god by the ancient

institutions and religious ordinances of Larinum. There was quite a

large number of them, and as well, just as the case in Sicily with the

many Venerii, so too these men of Larinum were reckoned to be in the

familia of Mars. But quickly Oppianicus began to demand that these

men be free and Roman citizens.

The Martiales, who are likened to the Sicilian Venerii, are neither free nor citizens. Furthermore, they are reckoned to be in the familia of Mars. To be in a Roman-style familia is not to be a member of the blood clan, a concept better expressed by the word gens, but to be a member of a household, including the status of household slave. The Venerii, like the Martiales, then, were slaves belonging to a deity, and thus the temple, but otherwise likened to the state servi publicani. It is easy to understand how the sacred servi would be under the protection of their patron deities. However, as stated in Cicero’s anecdote about Agonis, she was a former Veneria, a liberta of Venus Erycina. Nevertheless, she claimed that both she and her own household still fell under the goddess’s protection. Thus two classes of sacred slaves, one actual slaves, one freedpersons, but equally under divine protection.

[...]

In this way, even though the former Veneria (or Martialis) was technically now a liberta, she remained to some extent within the famila of Venus, acquiring the goddess’s protection not only for herself, but also for her own household familia who might be called upon to help in the service of the deity. If we might accept that Cicero’s Venerii were the Latin “translation” of Strabo’s hierodules and hiera sômata, we must question Strabo’s understanding of the Sicilian practice. For, once again, Strabo claimed that the hierodules (and presumably the hiera sômata?) were female. It is very clear from the Roman evidence, however, that the Venerii of Eryx were not exclusively female. To give a quick summary of the various uses and abuses of these Venerii as enacted by Verres and condemned by Cicero in Verres II,

They acted as provincial police either directly under the governor or

indirectly under his agents (3, 61; 74; 89; 105; 143; 200; 228). They

made arrests and executed not only the sentences of the governor’s

court (2, 92–93) but also, it would seem, the decisions of the tithe

contractors (ibid., 3, 50); ran errands for the governor and carried out

his commands that were not of a judicial nature (3, 55; 4, 32); took

charge of the moneys and goods he ordered sequestered (3, 183; 4,

104); acted as bodyguard to his satellites (3, 65); were the beneficiaries

of donations forced upon the cities by the governor (3, 143; 5, 141);

collected the offerings, dues and emoluments accruing to the temple

of their goddess (2, 92–93).

It may be my own deeply rooted sexism showing, but I have a terrible time imagining that these functionaries were female, especially the bodyguards (although I suppose having sacred prostitutes as police, tax collectors, and bodyguards might have contributed significantly to local feelings of goodwill toward the Romans . . .). While some of the Venerii, and thus the hiera sômata, were certainly female, as is evidenced by Agonis, many were also male.How might we understand Strabo’s “mistake”? First, we must remember that by the time of Strabo’s writing the “plethora of sacred bodies had left.” Strabo never actually saw any of these hiera sômata, and thus he was writing based on tradition. Furthermore, it is possible that Strabo allowed his knowledge of the Corinthian custom to color his understanding of the Erycinian. In both instances, both set definitively in the past, Strabo understood that the general populace dedicated hierodules to Aphrodite. In both instances, the sanctuary itself was famous for its wealth in times of old (see below). It is possible, then, that Strabo’s “knowledge” of Corinth colored his view of Eryx, claiming that only female hierodules (but not hetairai!) were originally associated with the sanctuary. As Strabo seems to have understood it, the temple of Aphrodite at Eryx was once populated by a number of female hierodules. Unlike Cicero, he was not entirely specific about whether the temple directly owned the hierodules; he merely related that in olden times the temple was “filled with” hierodules, and later, when the going got tough, the sacred bodies left. This stands in contrast with Cicero, who relates that the temple did in fact own Venerii, both female and male.

In neither the Strabonic nor the Ciceronian accounts is there any evidence that would suggest that the normal service activity of the hierodules for the temple was sacred prostitution, either for the males or for the females, just as there is no suggestion in the literature that the Martiales, who are compared to the Venerii, are prostitutes for Mars. Nevertheless, the “sacred bodies” are often taken to be sacred prostitutes, the descendants of the female hierodules of earlier times who are also, of course, understood to have been sacred prostitutes. Furthermore, their sacred meretricious profession is generally traced back to the early Phoenician/Punic habitation of the site. The sacred prostitutes of Erycine Aphrodite are a holdover from the sacred prostitutes of Erycine Aštart.As with Corinth, then, sacred prostitution is understood to emerge from an initially Semitic influence. This, of course, is hogwash. As discussed previously, there is no “Semitic” sacred prostitution (see Chapter 2). Theword “hierodule” does not mean sacred prostitute and does not come into use in the Greek (much less Roman) vocabulary until the mid-3rd century bce. Thucydides fails to mention the temple slaves when discussing the apparent wealth of that sanctuary of Aphrodite of Eryx in 6.46.7–11 of his Peloponnesian War:

And leading them to the sanctuary of Aphrodite in Eryx they showed

them the dedications, phiales and wine jugs and incense burners and

not an insignificant amount of other paraphernalia which, being silver,

presented an appearance of much greater worth by far.

Although it is never safe to argue from negative evidence, the evidence from Thucydides strongly suggests that there were no “sacred slaves” of Erycine Aphrodite in the fifth century bce, a point after the Greeks had assumed political and cultural control of the island from the Carthaginians, as well as the cult of the Erycinian. There can be no continuity, then, between the supposed sacred prostitutes of the cult of Erycine Aštart and those of Erycine Aphrodite or Venus. Strabo’s section 6.2.6 is not evidence for sacred prostitution in Sicily; it is a commentary on the women dedicated to a temple of Venus and how, in “modern” (for Strabo) times, the temple and town, having fallen on hard times, has fewer temple attendants – hierodules, hiera sômata, Venerii – than previously. Nothing indicates that the hierodules had prostitution as an aspect of their temple service, either for the males or the females.

Stephanie Lynn Budin, The Mith of Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity, 184-191

#women#history of women#women in history#history#historical women#Greek Sicily#roman sicily#erice#Province of Trapani#Stephanie Lynn Budin#sacred prostitution#people of sicily#women of sicily#culture

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

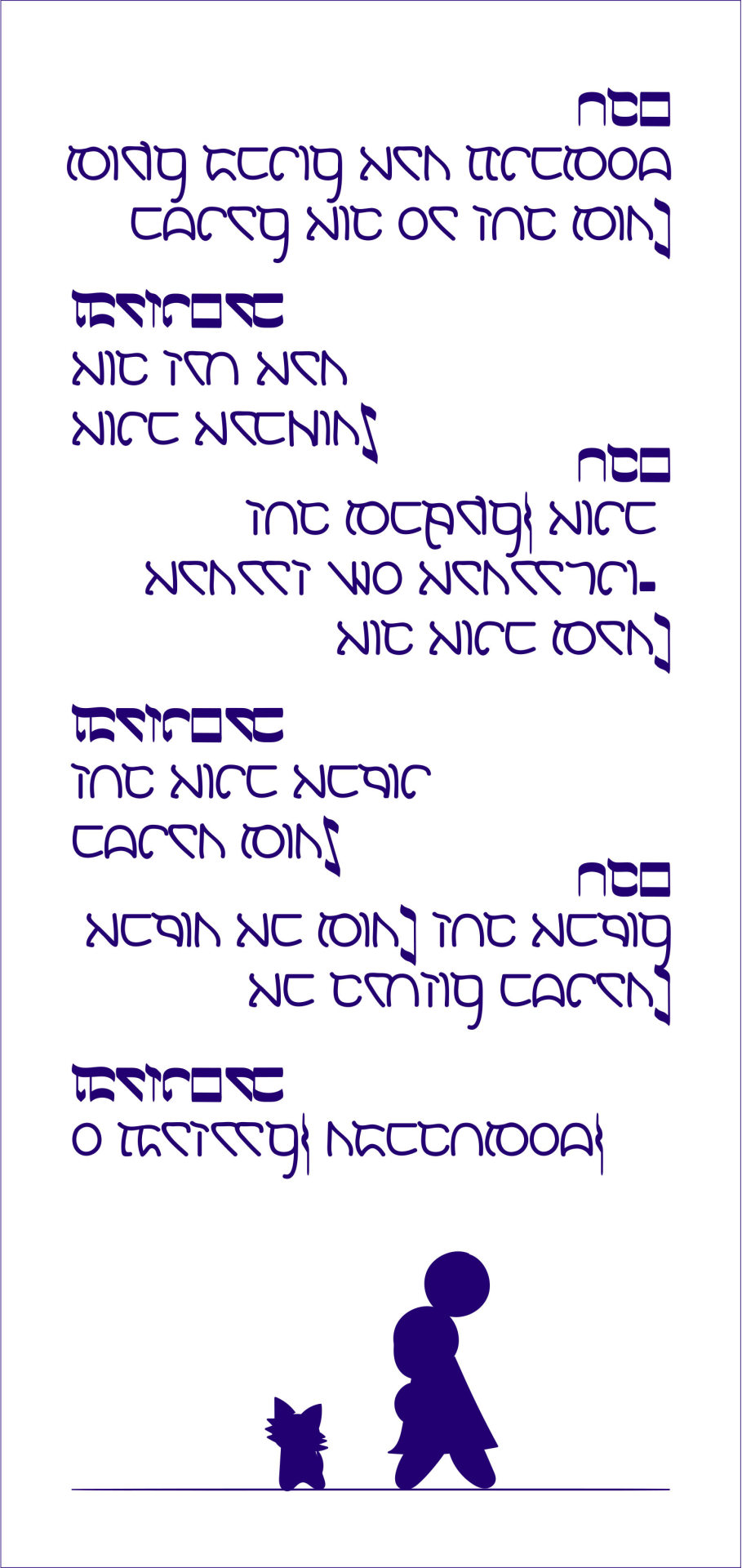

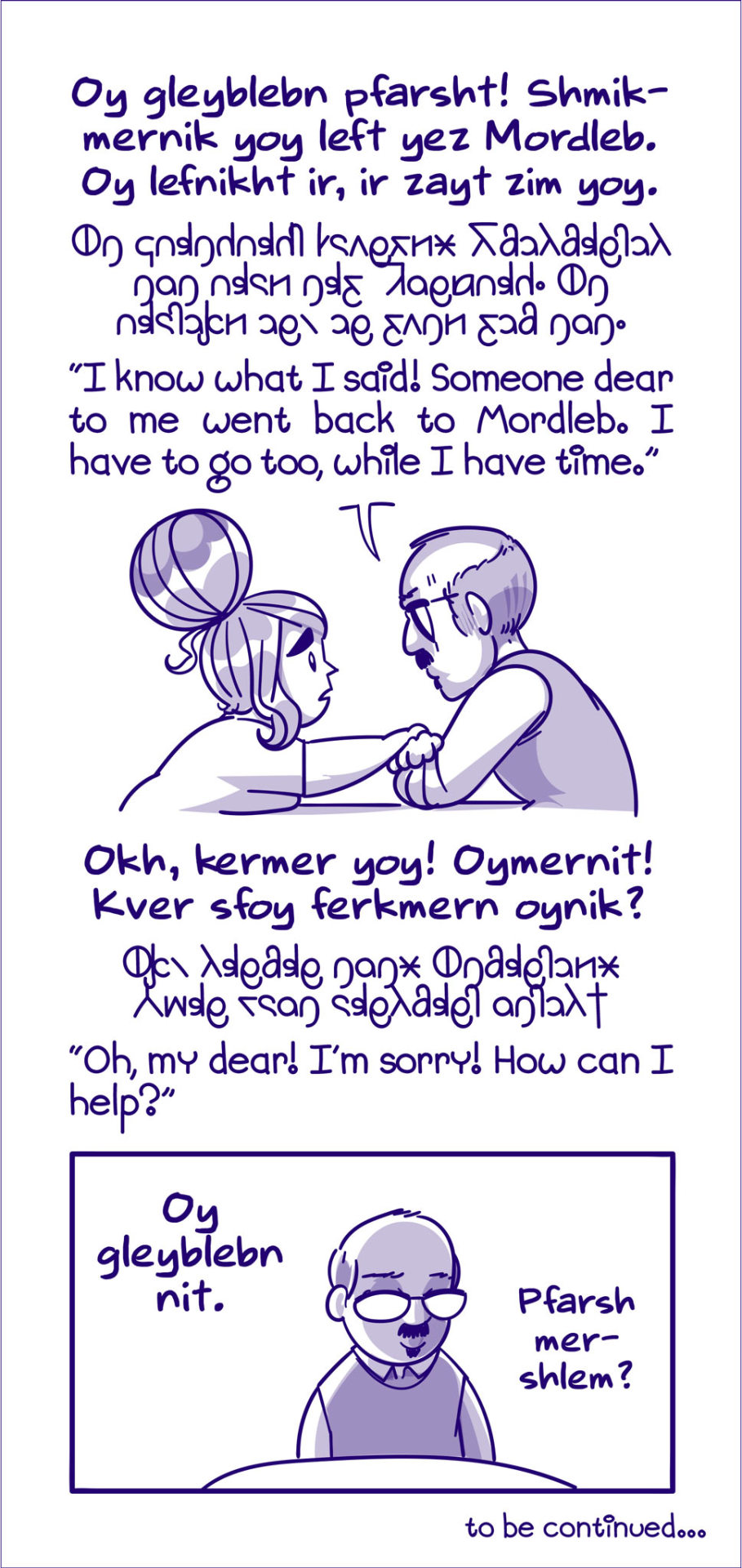

Conlang Corner 4.3.2024

i try to update Conlang Corner on Mondays.

i know we're all broke. here's my ko-fi anyway.

https://ko-fi.com/wobblydev

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

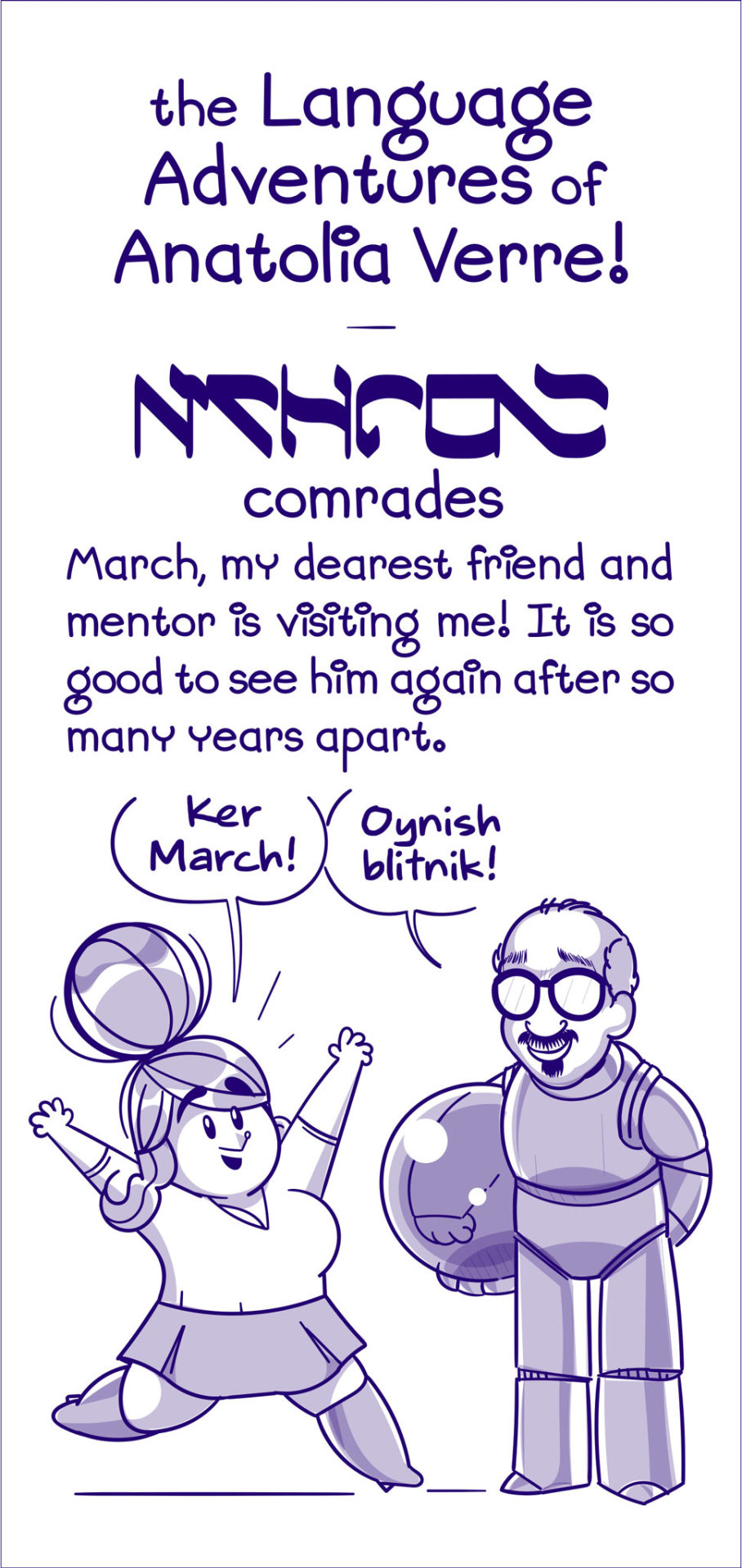

Conlang Corner 3.25.2024

Conlang corner is updated Mondays mostly?

If any of this is enjoyable, maybe toss me a few bucks?

https://ko-fi.com/wobblydev

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

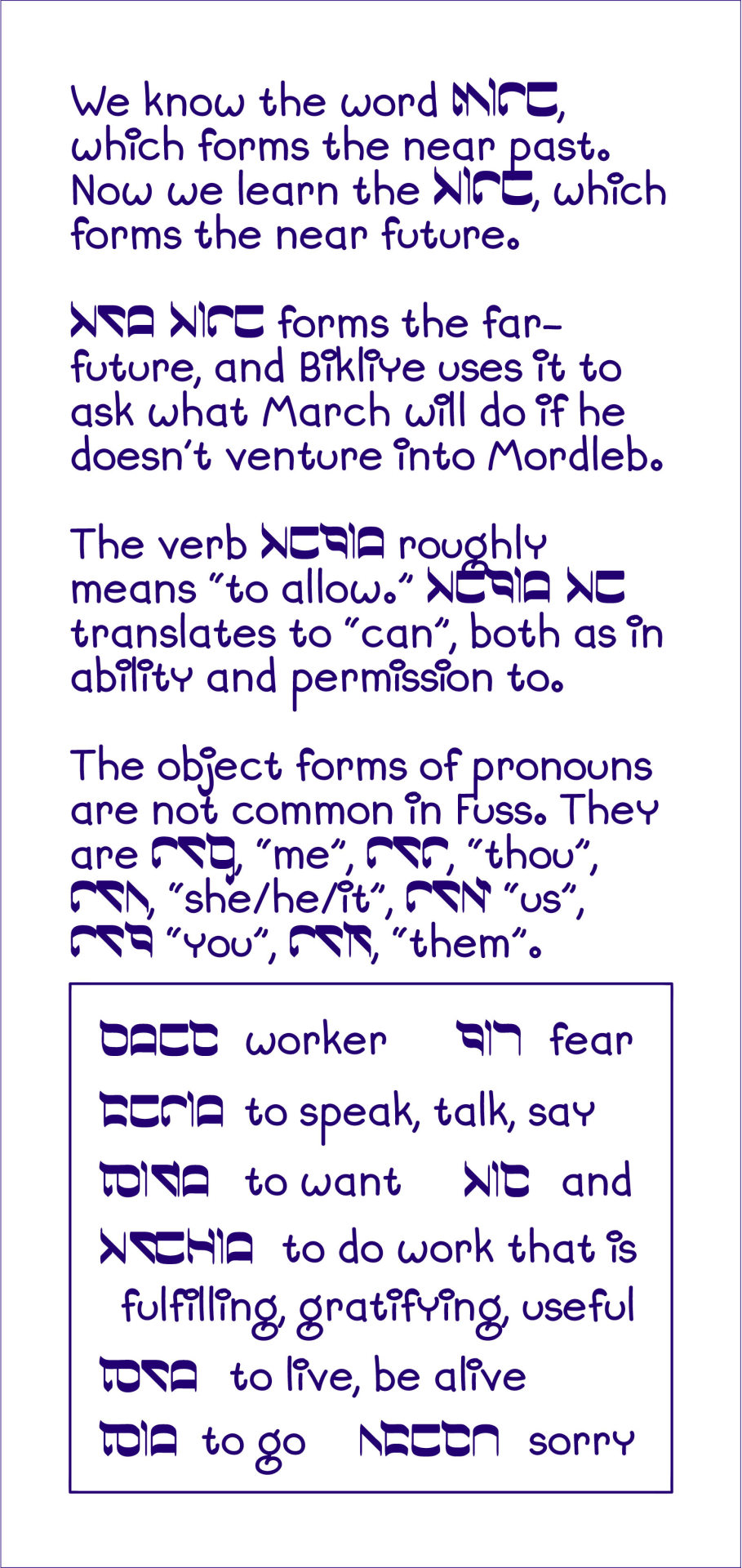

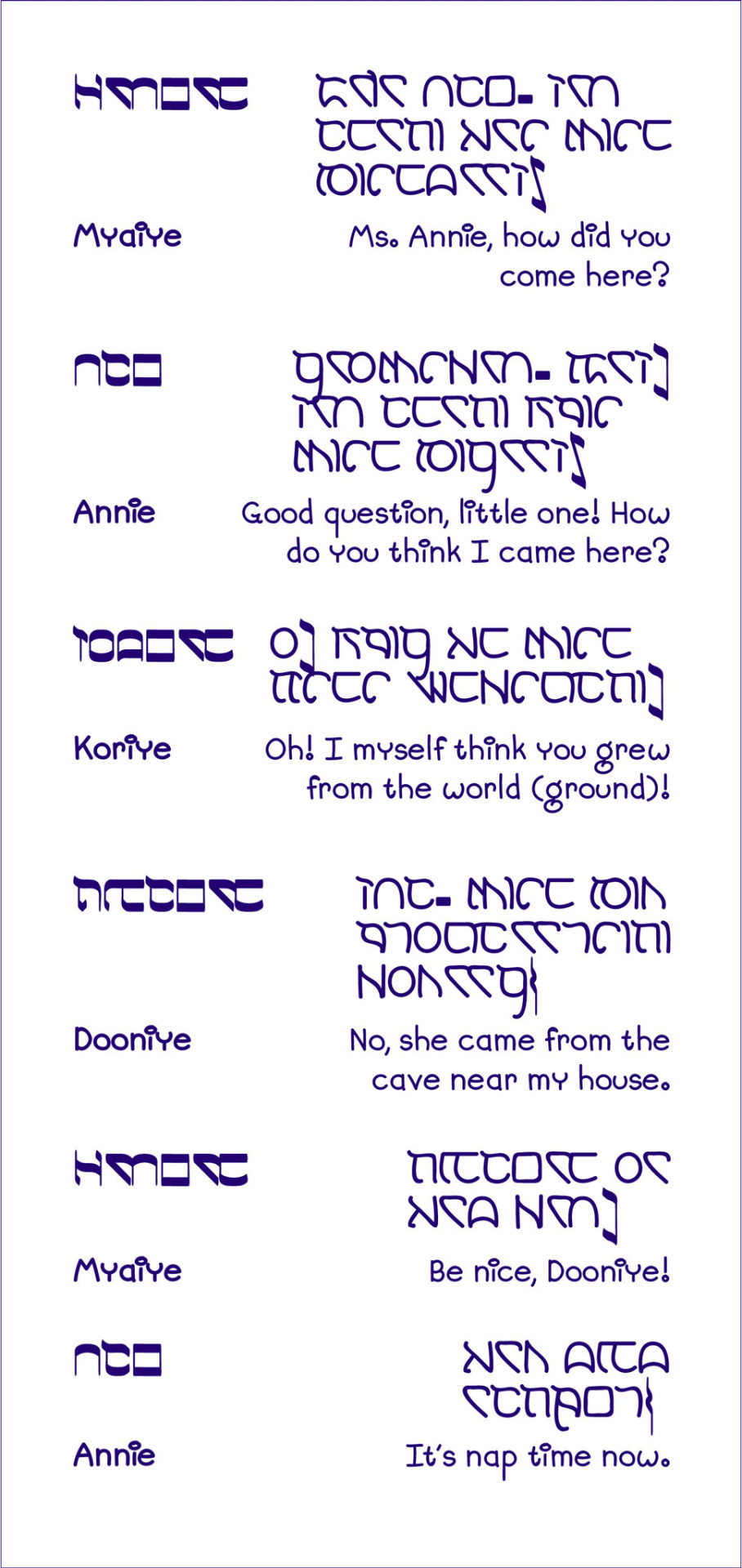

Conlang Corner 1.8.2024

another day late, but it feels good to continue this silly little project.

the conlang corner is updated every Monday! (or Tuesday i suppose)

https://ko-fi.com/wobblydev

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conlang Corner 2.27.2024

the conlang corner is updated every Monday! (or whatever day i have spoons and time 😿)

#wobbly dev#wobblydev#web comic#conlang corner#conlang#mordleb#anatolia verre#farband#fuss#pfarshleb

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

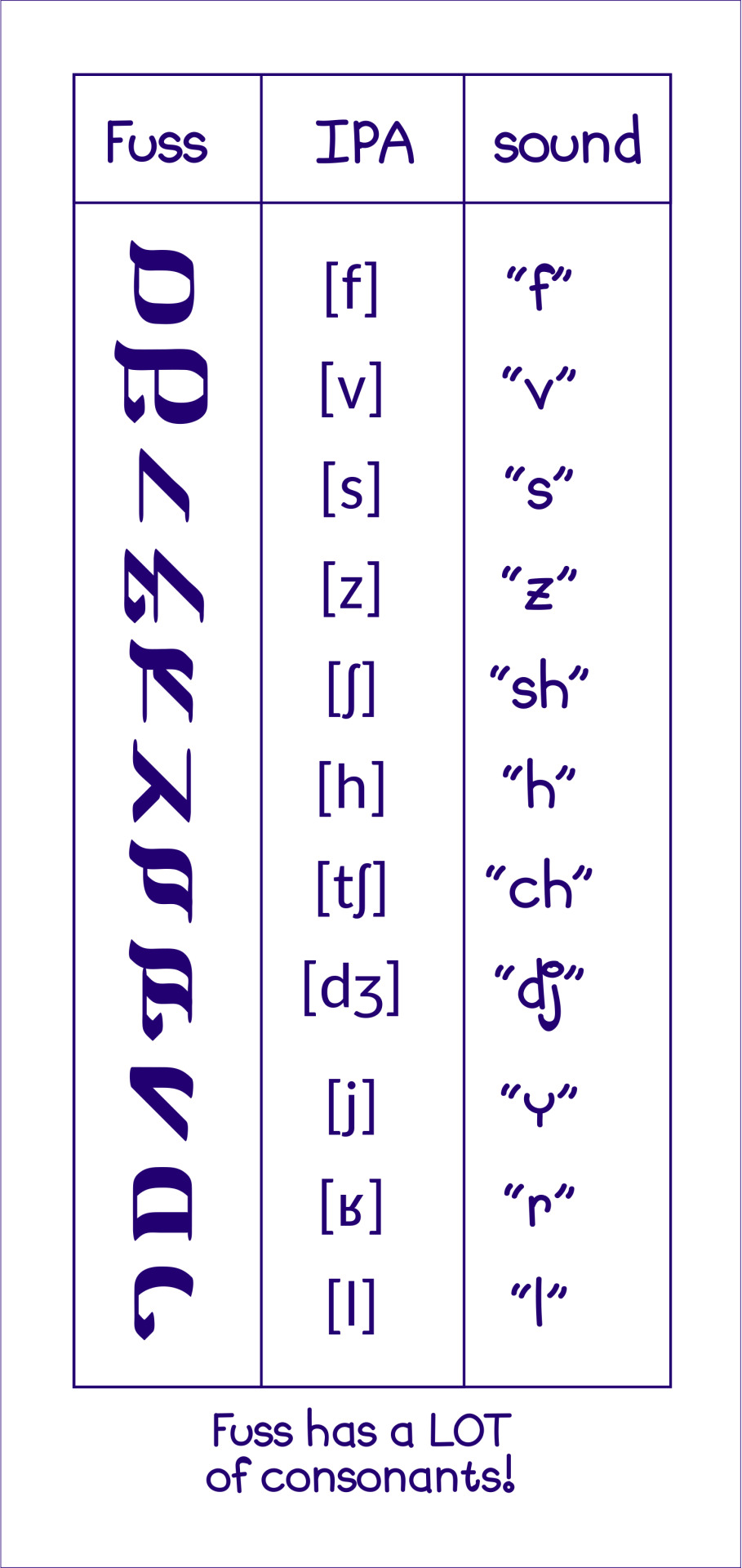

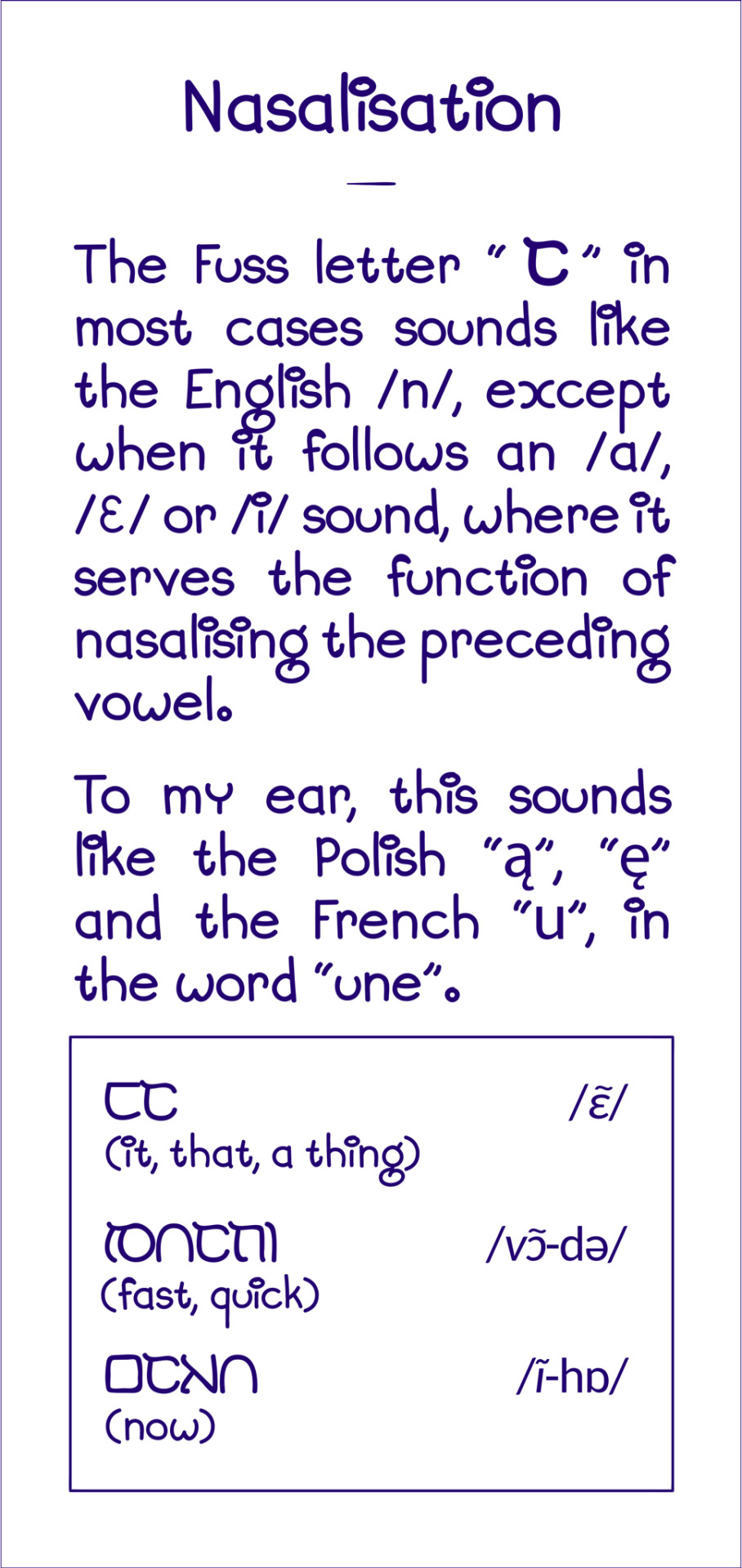

Conlang Corner 12.18.2023

i think we've got pronunciation all finished! feel free to ask questions if you feel there are ambiguities 😸

the conlang corner is updated every Monday!

https://ko-fi.com/wobblydev

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

an extra piece for today's Conlang Corner. Annie likes to sketch people she meets and spends time with in the frames she visits. this is her pencil sketch of Bikliye.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

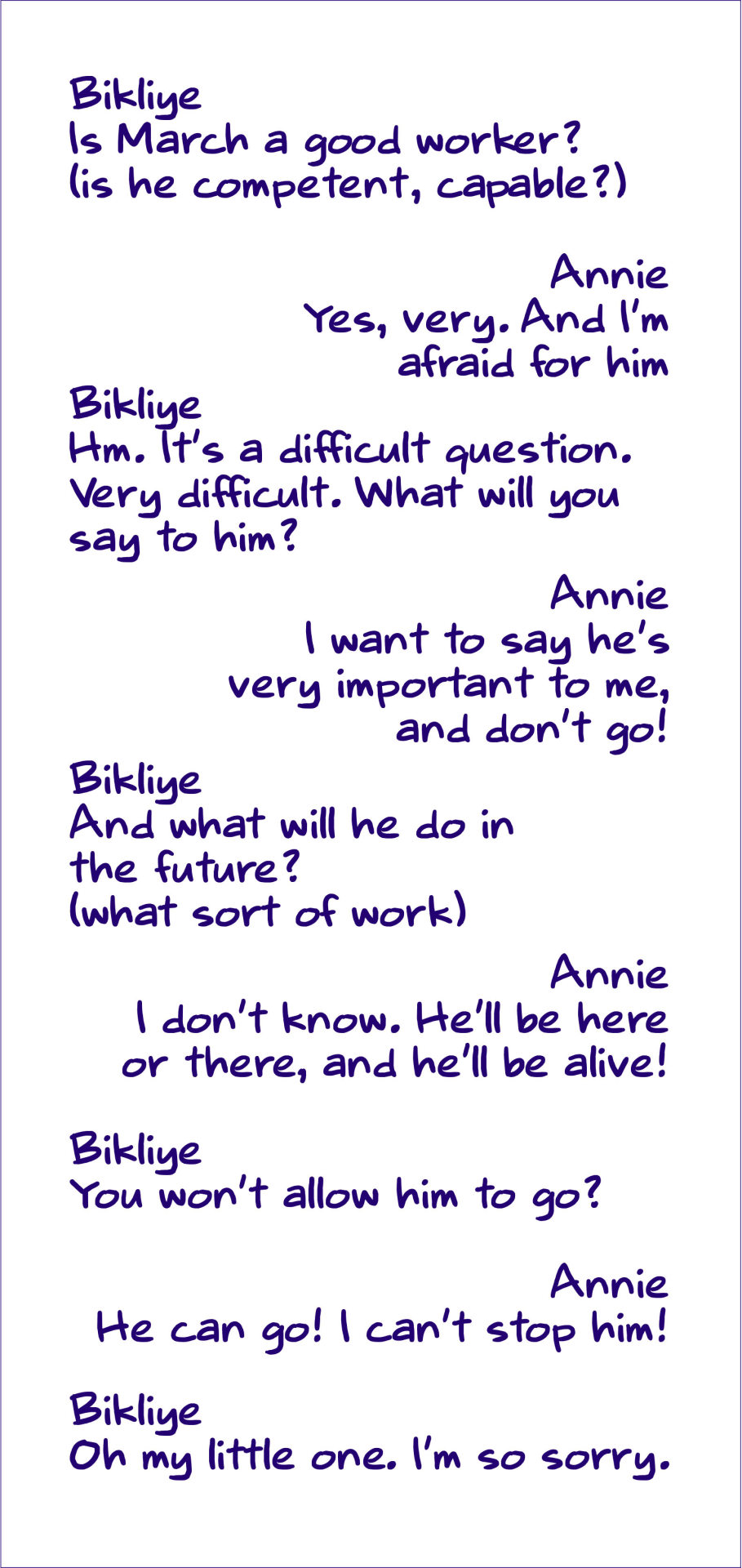

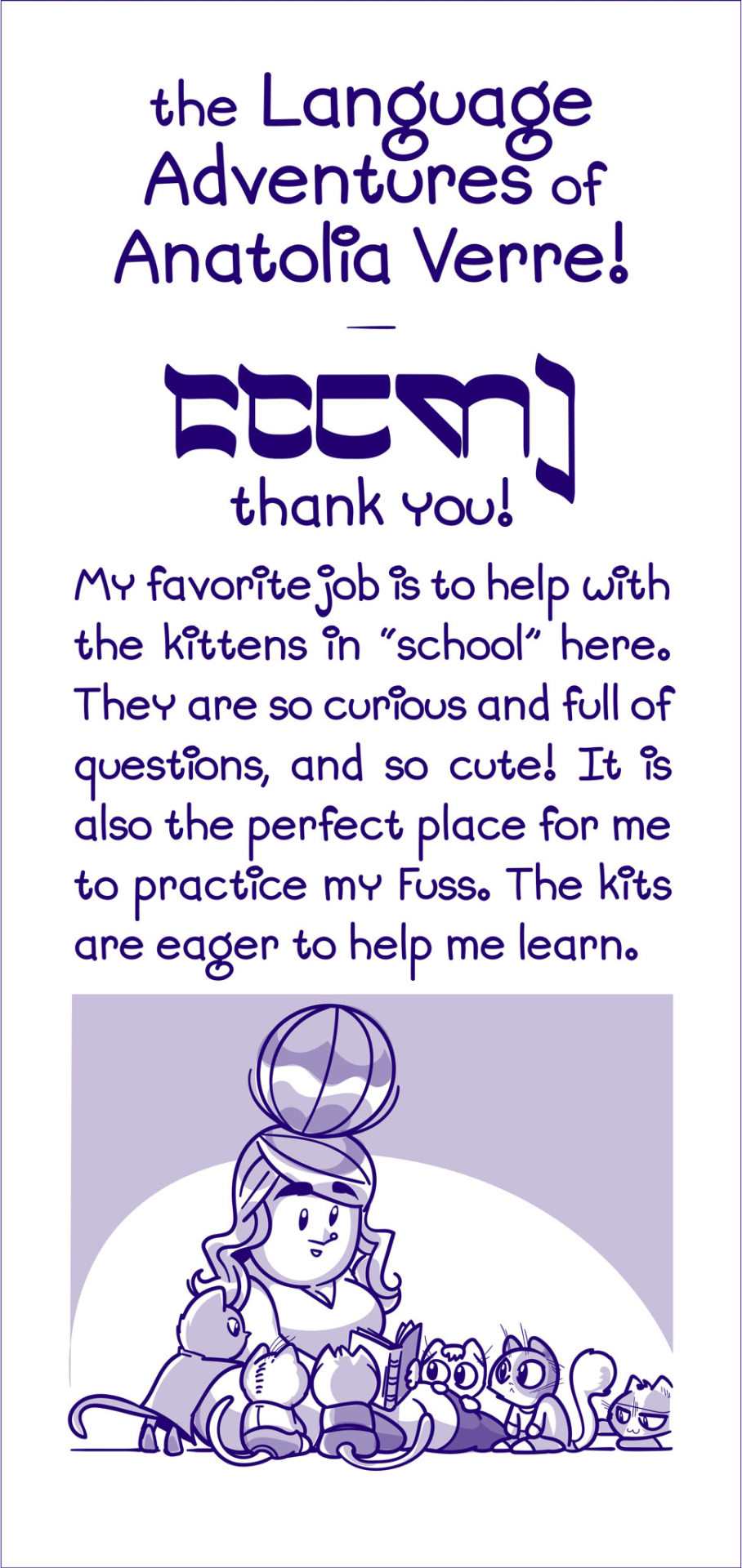

Conlang Corner 1.16.2024

i realised too late i never actually incorporated "thank you" into last week's conlang corner. ah well, next time.

the conlang corner is updated every Monday! (or Tuesday depending)

https://ko-fi.com/wobblydev

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ana Verre's diary: Day 1

now and then we will leave Farband and look at Anatolia's diary entries from her very first assignment as a frame-skipper.

1 note

·

View note