#h. leivick

Text

The Holy Poem

by H. Leivick, translated from the Yiddish by A. Z. Foreman

With my holy poem

Clenched between my teeth

From my wolf cave—my hole, my home—

I go out and I roam

From street to street:

As a wolf with a wretched bone

Clenched between his teeth alone.

There is prey enough in the street

to sate a wolven hate,

and sweet

is the humid blood that drips

from flesh, but sweeter still

is the dry dust settling

down on jammed lips.

Struggle on the street,

The call of throats.

Let me this once come out tonight,

A deathtooth bite.

That bite is me.

But I don't come to gnaw.

I hunch into my little self

With head beneath my paw.

Back to my hole I head

And lump onto my bed,

But I am awake,

Untired from holding clenched

Between my teeth alone

This holy poem

As the wolf his wretched bone.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

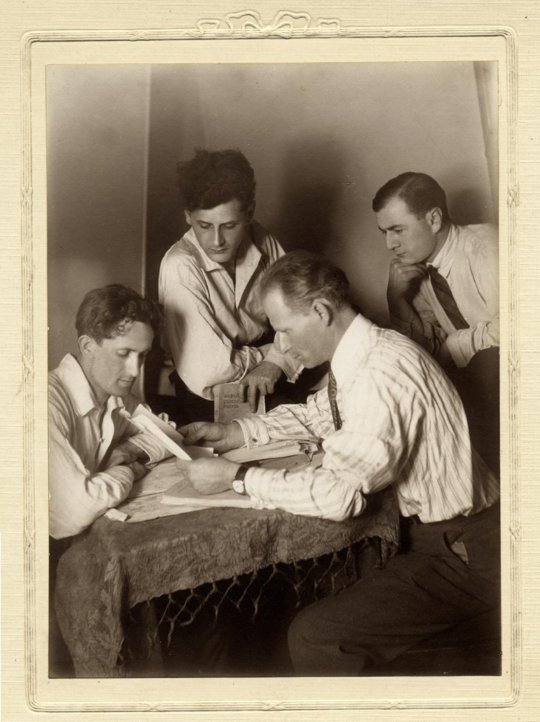

Yiddish writers Oyzer Varshavski, Peretz Markish, H. Leyvik, and another unidentified man pose for a studio portrait. Markish holds a 1922 printing of Russian symbolist poet Andrei Bely's The Silver Dove.

Photographed by J. Deutscher, Paris, 1924

#peretz markish#oyzer varshavski#ozer warszawski#h. leyvik#h. leivick#leivick halpern#1924#yiddish#jewish history#jumblr#yidishkeyt

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

shver un shverer • in living word i have captured the doubt in fear- the bitter and angry loneliness…

(der goylem- h. leivick, translated into english by me)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I need to see Andrzej Marek's production of H. Leivick's Golem with set design by Andrzej Pronaszko and Szymon Syrkus and then

Fight Słonimski about his interpretation, scream about how the watered-down, diluted liberal-press use of "hate" (affect, emotion) as a placeholder for "violence" (action) has not changed in one hundred years, yell about how Leivick is engaging with a Yiddish-language and Russian-language Jewish polemic that has been ongoing since 1905 about the liberatory potential or destructive consequences of revolutionary violence/violent revolution, about diaspora nationalism vs. class-conscious socialist solidarity and coalition building despite antisemitism / internationalism uber alles, these debates periodically flare up in the press and among political parties, it happened with the 1905 revolution and its attendant pogroms (An-sky argued with Dubnow in Russian tolstye zhurnaly, Zhitlowsky argued in the US Yiddish press), it happened with the McKinley assassination, it happened, of course, after 1917! Anachronistic use of folklore and Jewish legend and Biblical allegory to analyze contemporary political tendencies were Tools of the Trade, as were apocalyptic motifs and the trenchant critique of "false messiahs" and explosive entropic violence in the name of a Cause (self-defense, self-determination, justice justice will be done). Totally typical and temporally topical. Leivick's play addresses the Bolshevik Revolution but something tells me Andrzej Marek's staging addresses Sanacja too, given the timing

Constructivist sets are 100% appropriate here and Słonimski should not be a theater critic, he can't "read" a stage OR a text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

March 5-8 Links

GROUP 1

Fashion

https://crfashionbook.com/fashion-a33417774-robots-runway-fashion-alexander-mcqueen-chalayan/

https://www.elle.com/fashion/a33080297/virtual-fashion-shows-avatar-models/

https://www.ssense.com/en-us/editorial/fashion/do-androids-dream-of-balenciaga-ss29

https://willrobotstakemyjob.com/models

https://trendland.com/moncler-genius-first-ai-campaign/

https://fashionweek.ai/

https://wwd.com/business-news/technology/what-will-ai-mean-for-fashion-brands-design-1235511750/

GANS

https://stylegan-human.github.io/

https://3dhumangan.github.io/

https://app.runwayml.com/models/runway/AttnGAN

Design Tech

https://news.fitnyc.edu/2018/02/01/students-team-with-ibm-and-tommy-hilfiger-to-utilize-ai-to-elevate-design-manufacturing-and-marketing/

https://dtech.fitnyc.edu/webflow/index.html

https://dtech.fitnyc.edu/webflow/projects.html

Conceptual

https://edition.cnn.com/2023/03/04/middleeast/protests-iran-schoolgirls-poisoning-intl-hnk/index.html

https://vimeo.com/420277936

https://www.seiyaku.com/customs/vestments.html

https://ubibliorum.ubi.pt/bitstream/10400.6/11286/1/7943_16587.pdf

https://culture.pl/en/article/15-historical-quirks-that-make-poland-so-different-from-the-rest-of-europe

https://www.cairn.info/revue-monde-chinois-2020-3-page-12.htm

https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1079&context=etd

GROUP 2

Open Simplex and Perlin Noise

https://www.npmjs.com/package/open-simplex-noise

https://www.tumblr.com/uniblock/97868843242/noise

https://www.meetup.com/volumetric/events/161770192/

Werewolf and Othering

http://poemsintranslation.blogspot.com/2019/08/h-leivick-holy-poem-from-yiddish.html

http://www.otheringandbelonging.org/the-problem-of-othering/

Trauma

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bRDuc3IdOn8

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massacres_of_Poles_in_Volhynia_and_Eastern_Galicia

GROUP 3

Stable Diffusion

https://sites.google.com/view/stablediffusion-with-brain/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nsjDnYxJ0bo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OdRxIKv9z9w

V2V Models

https://research.runwayml.com/gen1

https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.03011

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2302.03011.pdf

1 note

·

View note

Text

h. leivick, “i do not say” ; translation by me

1 note

·

View note

Link

Spooky, scary.

#am I reposting myself today? damn right I am#with the corollary that if I updated this every year I would add in Argentina and Shylock this time#I reread H. Leivick recently and it is still awesome#I can't believe it exists#I miss this but I still think this was my favorite piece#and if you get the gist of what I'm writing pretty relevant right now#a nice jewish tag

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

figured u might be able to answer this, so: what is the best werewolf media? especially if it has lesbian/sapphic werewolves but honestly i'm not too fussed. also i prefer books to films/tv shows but again im not too fussy. i just think werewolves are a neat idea but i haven't really consumed any media containing werewolves except for h*rry p*tter

yes! anon, i am your woman. werewolf media in general is either like - the best, or the stupidest. it depends on where people’s priorities are and generally i don’t think people understand what is great about werewolves in fiction.

did you know that the supposed first werewolf film (”the werewolf” from 1913) is about a navajo woman who becomes a witch that transforms into a wolf to kill white settlers? every werewolf narrative that is NOT transgressing lines of society, poverty, disability, gender or desire is failing absolutely.

but also - you need a nasty transformation scene that makes your skin crawl and you have got to have the guts to GO THERE. anyone else read hemlock grove? i’m not putting it on this list because the book itself is Not amazing but that werewolf scene?? i still think about it. so gross.

in any case - here are some next-level-tier werewolf stories for you to enjoy & be grossed out by:

mongrels by stephen graham jones - the thing sgj does best is take the broad tropey concepts from a genre of horror and make them feel gritty and real and lived in. a werewolf story about family and poverty and indigenous identity. also just a good yarn. top of this list for a reason.

the devourers by indrapramit das - queer south asian speculative fiction & it is both gross and sexy as hell. please read this book.

the bloody chamber by angela carter - short story collection of reinterpreted fairy tales and totally metal

the cycle of the werewolf by stephen king - not his best work by any stretch but it does some compelling things with blame and intention that i like

“twilight in the towers” by clive barker (in the cabal short story collection) - he’s certainly not for everyone but when clive gets it, he gets it

ginger snaps (film) - THE werewolf-as-teen-girl transgression movie!

an american werewolf in london (film) - kind of the classic werewolf movie but imo it holds up

good manners - a brazilian lesbian horror werewolf melodrama

penny dreadful - i was just thinking about my darling werewolf cowboy ethan chandler yesterday!

this isn’t any of those things specifically but my pal marisa is writing a series on werewolf narratives as queer allegories -- it looks at some of these stories and others and is fascinating and great! read it here.

objectively - the greatest werewolf narrative ever written is “der volf” (”the wolf”) by yiddish poet h. leivick. after his shtetl is destroyed and his community murdered, a rabbi transforms into a monster. he begins to take revenge on other jewish refugees who move into his destroyed town. a meditation on trauma, guilt, jewish identity and monstrosity that was written in 1920 but could have been written this year. but - it’s in yiddish and translations aren’t easy to find so -- good luck with that.

#and that is that on that !#all stories are about wolves#would love to know other people's suggestions but i'd also assume if i left something off it was intentional#no teen wolf for me lol#Anonymous

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ruth R. Wise, A Yiddish Poet in America, Commentary Magazine (July 1980)

The decline of Yiddish in America among all Jews except the Hasidim has had important consequences, some of which have only gradually come to light. Initially, the sacrifice of Yiddish, the internal vernacular, was a relatively small price for European Jewish immigrants to pay in return for English, which gave them direct access to the material and spiritual opportunities of America. Jews, after all, have managed innumerable linguistic adaptations throughout the millennia, and while Yiddish enjoyed a longer history and fostered a richer culture than most other Jewish languages, it was only one of several Diaspora vernaculars created by Jews and subsequently, in altered circumstances, abandoned. In the modern period, wherever political emancipation promised civic equality, Jews learned and adopted the local language, always more responsive to the carrot than to the stick, to the proffered opportunity than to any punitive measures against them. Nowhere was the carrot more enticing, the promise more golden, than here in America.

Only a false nostalgia for the bad old days would suggest that the adoption of English was not worth the risk to Yiddish, or that linguistic assimilation was a cultural mistake. Nevertheless, now that American Jews have become Anglicized, one can afford to recognize the debit side of the ledger. The abandonment of Yiddish within a single generation meant the loss, not of some antique property, but of a highly developed contemporary resource, the national storehouse of consciousness and expression. Though the loss of Yiddish is often mourned sentimentally, as if some beloved grandmother had died leaving one last anecdote unrecorded, its decline is actually of more immediate and personal consequence. Yiddish is the crucible in which most of the modern Jewish experience was forged. The complexities of the Jewish encounter with modernity are recorded in Yiddish folk and formal culture and in the language itself. Without Yiddish, descendants of European Jewry are without their 19th and early 20th centuries, bereft not merely of the traditional past but of the setting of their own immediate experience.

It so happened that among the immigrants to America were many budding Yiddish writers who would use their vernacular to interpret their individual and communal reorientation, and in doing so, bring their literature to new heights of excellence. But by the time they were at their best, much of their natural audience had become actively indifferent to Yiddish, and their children even more so. Modern American Yiddish culture was left without heirs, and the heirs without a culture.

There was something remarkably raw in the immigrant dedication to the future, an abandon not usually associated with the Jews, but characteristic of them nonetheless. No one captured this hard streak in the American Jewish immigrant character more effectively than the Yiddish poet, Moishe Leib Halpern (1886-1932), who was both its exponent and victim. An uncompromising realist, Halpern recognized that the pragmatism of the Jews seeking refuge in America was the necessary cost of their legendary national talent for adaptability. Yet he recoiled from the coarseness of the immigrant struggle for survival. He did not share the immigrant optimism, the faith in a better future as a reward for present hardship. As a writer, one of that select group of immigrants for whom the native language was indispensable and non-negotiable, Halpern saw in the weakening of Yiddish his own personal doom for which there could be no social compensation. Frayed by the practical difficulties of eking out a Yiddish writer’s living, and progressively estranged from the society of transplanted Jews, Halpern exposed the most painful and desperate aspects of making a new home, both for those who successfully managed the feat and for those, like himself, who did not.

To some degree, of course, all the Yiddish writers in America were sooner or later affected by the evaporation of their language. The greater persistency and intensity of Halpern’s sensitivity to the problem derived, as he was aware, from the circumstances of his childhood. Long before he came to America, an earlier process of uprooting and adaptation had already organized his contradictory feelings about belonging and estrangement. His coming to New York at the age of twenty-two followed a previous period of disorientation which foreshadowed his immigrant life.

Moishe Leib Halpern was born in 1886 in the Galician market town of Zlochow, which had been under Austrian rule since 1772, and which comprised about 10,000 inhabitants, just over half of them Jews. His father, who came from a family of merchants in Odessa, ran a local general store. In raising his only son, this traditional Jew embarked on an unusual plan. Having sent the boy to cheder and to a local Polish school, he then took Moishe Leib, at age twelve, to Vienna where he enrolled him in a course of applied art so as to guarantee his professional independence. Though the boy showed talent as an artist and sign painter, he thwarted his father’s design by gravitating to literature. He began a study of German verse and took his own first tentative steps as a German poet. Halpern also frequented the Vienna catés, where the arguments of the Jewish socialists and Zionists successively won his allegiance.

By the time he returned to Zlochow, at the age of twenty, he was effectively without a career and a cultural stranger to his birthplace. His boyhood friends could not follow his political arguments, delivered as they were in German or in an impossibly Germanic Yiddish. Having strong literary ambition themselves, they persuaded him that as a would-be writer he was wiser to use his native Yiddish tongue, which was anyway evolving into a lively artistic medium. Somehow the cosmopolitan finish of Vienna did not suit the indigenous cultural ferment of his birthplace, and it was he rather than his provincial school chums who gave way. He turned back to Yiddish and submitted his first poems in that language to the Galician Yiddish press.

But there was a second area of expectation in which Halpern could not comply. Some of his contemporaries were already in uniform in the Austrian army, where he would also have to serve. Rather than submit to induction, he set out for America, arriving in New York in the latter part of 1908. He had found himself a stranger in his home, and was now twice a stranger in the city of Jewish ingathering.

_____________

Halpern’s arrival in America coincided with a great cultural upsurge on New York’s Lower East Side. He became associated with a movement of fledgling writers called Di Yunge, the young, in deference to their audacity and innovativeness. These were young men from a diversity of backgrounds and from various cities, towns, and villages that spanned the map of Eastern Europe. Coming together in the common insecurity of immigrants and with the common ambition of becoming great writers, they stimulated one another in comradeship and competition. Most of them were without special training or profession, and the regular jobs they found to support themselves—in small factories, as house painters, newsvendors, paperhangers, waiters, even shopkeepers—eventually drained the energy required for steady writing. But there were enough among them who succeeded in bringing fame to the designation, Yunge: Mani Leib, the handsome lyricist from the Ukraine; Zishe Landau, poet, scion of a Polish rabbinic family; Reuven Iceland, poet, one of the chief chroniclers of the group; David Ignatoff, energetic novelist and short-story writer from the hasidic heartland of the Ukraine, who edited the group’s first major publications; Joseph Rolnick, an unassuming, evocative poet of moods and landscapes; I. I. Schwartz, the most learned Jew among them, epic poet and gifted translator; Joseph Opatoshu and Isaac Raboy, experimenters in long and short forms of fiction; H. Leivick, escapee from a sentence of lifetime exile in Siberia, poet and dramatist; Moishe Nadir and Moishe Leib Halpern, from neighboring towns in Galicia, the mischievous rebels within this movement of self-declared rebels.

The group—actually, like most literary groups, an informal cluster of like-minded writers who would soon go their individual ways—was overtly rebellious only in its initial phase. Its members opposed the national and social orientation of the work of their predecessors, the commercial impulse of the Yiddish press, and the sense of communal responsibility that was expected of Jewish writers in a Jewish language. Like knights of a medieval romance, or like the Symbolists whom some of them acknowledged as models, they vowed to serve di sheyne literatur, belles-lettres, with pure aesthetic passion and undivided loyalty. Preferring (for the most part) poetry to prose, they turned from the public spirit of Yiddish writing to subtler, intricate explorations of the individual self in all its moods.

Although most of the young writers originally subscribed to this mild aestheticist position, they were caught up before long by local and international events, and they responded, no less than the mass of their fellow immigrants, to pressures from the very movements they had tried to resist. Several of the Yunge had been members of anti-czarist revolutionary organizations before coming to America. When the revolution of 1917 appeared to actualize their youthful dreams, they were inevitably affected, and in some instances moved to political alignment with Communism. Three almost simultaneous events—the eruption of World War I, the Bolshevik Revolution, and the issuance of the Balfour Declaration—in one way or another claimed the allegiance of them all.

Halpern was generally less sociable than his literary colleagues and everyone who met him in the early immigrant years commented on the solitude which seemed particularly pronounced in him. His fellow poet, Mani Leib, recalled that “we, his friends, like all other Jewish immigrants, also bore the fear of this wondrous unknown called America. But somehow we . . . gave in, adapted ourselves, ‘ripened’ and gradually became . . . real Americans. Not Moishe Leib. He could never compromise or bend.” Though he contributed to the group’s many publications and little magazines, he was slightly apart from the others, the lone wolf, or, as the play on his name suggested, the brooding Lion, Moishe Leib. Almost alone among his fellow writers he failed to find steady work in the small factories, manual trades, or editorial offices where most of the others eventually made their living, and this economic precariousness, which continued practically without interruption until his death, contributed to his image as a troubling nonconformist, and to his artistic distance.

_____________

Moishe Leib Halpern’s poetry was as distinctive as he. Against the general mood of literary quietude and resignation, of nostalgic reminiscence and submissiveness, Moishe Leib was strident and mocking, equally impatient with the past and the present. His verse sought out the disjunctive rhythms and the coarsest idioms of everyday speech. His images were shabby or grotesque. His first book, In New York, published in 1919, which established his reputation as one of the most interesting voices in the post-classical phase of Yiddish literature, took for its setting and subject the new world—the metropolis ironically reinterpreted as a modern garden of Eden.

The grass in this paradise can be seen only under a magnifying glass; its trees have scarcely seven leaves; the watchman throws you out before you have even done any wrong, and no birds sing.

Is this to be our garden now

Just as is, in morning’s glow?

What then? Not our garden?

The book opens with this guarded celebration of morning and concludes with a phantasmagoric epic, “A Night,” in which the horrors of World War I storm the poet’s consciousness until they elicit from him a broken series of dirges.

The range of contents of In New York, from romantic lyrics and dramatic narratives to parodies and apocalyptic visions, confirmed not only Halpern’s artistic maturity but the sudden authority of the new American Yiddish literature. Beginning in 1919, and largely because of Halpern’s work, the tide of influence in Yiddish poetry flowed mostly outward, from America to Europe, reversing its earlier direction.

In the same year Halpern married a young woman whom he had courted for several years, and for whom he continued to feel a lifelong, if not exclusive, affection. During the war, he had somewhat isolated himself by his firm stand against conscription, attacking even those Jews who joined the Jewish Brigade of the British army. But in 1922, in the golden afterglow of the Russian Revolution, when the Communist daily newspaper, the Freiheit, began publication in New York, Halpern entered upon a brief, heady period of popularity. From the first issue of April 2, he was a regular contributor, with a ready forum for his poems, incidental essays, occasional theater reviews, and literary criticism.

The association with the Freiheit did not solve Halpern’s financial worries because the newspaper paid little and irregularly. As its featured poet, however, Moishe Leib enjoyed a wide audience and an acknowledged importance. He was sent on Freiheit-sponsored lecture tours to Detroit, Boston, Toronto, Winnipeg, Cleveland, and Chicago, speaking on the question of a proletarian literature and trying to drum up subscribers. With the help of admirers in Cleveland he put out his second book, Di Goldene Pave (“The Golden Peacock”), in 1924. These poems, far more aggressive in tone and explicit in their social criticism than the earlier works, were praised or condemned, depending almost entirely on the political orientation of the reviewer. In Warsaw, a literary column sponsored by the influential weekly, Literarishe Bleter, asked leading Yiddish writers to name and discuss their favorite author. Moishe Leib Halpern figured prominently among the contributors’ nominees—indeed, it was rumored that the frequent appearance of his name in this column was the newspaper’s main reason for suspending the series, since its editors did not share the enthusiastic opinion of their contributors.

By the mid-20’s relations between Halpern and the editors of his own newspaper, which had grown increasingly strained, reached the point of mutual repudiation. As Soviet authority exerted ever greater control over local American activities, the Freiheit was expected to toe the party line, and its contributors were put under similar pressure to conform. Halpern’s poetry was becoming so complex that the “proletarian” readership for whom it was ostensibly intended complained of its incomprehensibility. On his speaking tours, Halpern said exactly what was on his mind. With some regret and some relief, he was dropped. This left Halpern without any steady income, and, in a period of polarization among the various Yiddish newspapers and cultural organizations, without a base of support. With his wife and three-year-old son, he moved to Los Angeles in 1927, but was back in New York before the year was out. He was caught in political limbo between the Left whose militancy he was among the first to recognize and repudiate, and the anti-Communists, whom he could not join because to do so would smack of careerism and “selling out.”

In 1929, when the Freiheit’s condoning of the Arab massacre of Jews in Hebron shocked many of its supporters into rebellion, a new nonaligned weekly, the Vokh, was briefly launched. Despite the inclusion on its editorial board of such well-known writers as H. Leivick and Lamed Shapiro, and despite a host of prestigious regular contributors, of whom Halpern was one, the paper was never able to achieve financial stability and folded after a year. Halpern, plagued by poverty and ill health, both of which he camouflaged as long as he could, died suddenly after an undiagnosed stomach ailment on September 2, 1932. His death, in the throes of the Depression, and against the background of European political dangers, touched off a moment of anguish that had Moishe Leib at its center but encompassed much more. Once he was dead, beyond the squabbles of Jewish cultural life, it was easy to recognize his marvelous talent. At the same time, his death, as if momentarily exposing the dreary backstage of art, revealed the pitiful isolation of American Yiddish writers, the ugly effects of Communist dogmatism on Jewish intellectual life, and the weakness of Jewish culture in America once it was no longer receiving fresh infusions of European immigrants. The shock of Halpern’s death momentarily illumined both the unexpected achievement and its impermanence, like a comet’s bright flash.

_____________

By the time of his death, Halpern’s image as a poet had achieved an almost autonomous life, much as Sholem Rabinovitch’s fictional self-representation as Sholem Aleichem had done in the preceding generation. He was the smart-aleck immigrant, Moishe Leib, restless as a wolf and stagnant as a bear in his new surroundings, pursued by memory, spurred by a rage of conscience, and claimed by a talent that stuck to him as doggedly as cow manure to a bare foot. Though his language was startling and occasionally crude, Moishe Leib himself was discomfitingly familiar: he was the unassimilable element in the process of self-adaptation, the coarse particularism that could not be smoothed over, the mocking disclosure that the masquerade of refinement was uglier than what had gone before, and doomed to fail besides.

For most of the Yunge, poetry was a means of transforming their harsh and often degrading circumstances into something of intrinsic worth. Yiddish, a language heretofore associated with the rough prosaic task of daily survival, would be their instrument of purification, the inner flame of the poet’s aesthetic heat burning away the dross of experience to create perfect expression, a still life of distilled beauty. With the naive folk song as one model of purity, and the rarefied idealism of Russian mystics like Fyodor Sologub as another, the poets tried to bring their private perceptions and visions to sublimated expression.

Always in opposition, Moishe Leib reinvented himself instead as a street musician, drowning out the humiliations of immigrant life with his own raucous, aggressive ditties:

Children laugh in sport and fun

But I don’t want to be undone

Shake a leg, kids! Hop on by

One more punch then, in the eye.

One more spit!

In spite of it

With one jump everything is quit.

Inured to all with an evil name

From my pocket I pinch some bread

And swig from my flask, down from my head

The sweat pours and my blood’s aflame.

So as if to break

The drum, I bang

And then I make

The cymbals clang

And round and round about I spin—

Boom! Boom! Din-din-din!

Boom! Boom! Din!

—(Translated by John Hollander)

The disharmonious drummer, recklessly uncouth, tears away at every false façade, especially at the romantic idealizations of his contemporaries.

Chief among Halpern’s targets was the ubiquitous nostalgia for the old country, the gilded memories of home. Actually, before World War I, Halpern’s first major published work had been a ten-part poem tracing the voyage of a young man In der fremd (“Away From Home”) and using sanctified images of Polish Jewry to cushion the encounter with the great stone city. But even as this poem was being celebrated as a masterpiece of the new exilic literature, Halpern turned against his erstwhile source of solace. The ruinous scope of World War I, with its destruction of so many home communities, opened in Halpern a new range of anger. While others began to invoke forgotten grandmothers in idyllic landscapes, and as popular Yiddish culture settled into sentimental longing for “Mayn shtetele Belt,” Halpern recreated his shtetl, Zlochow, as a den of hypocrisy, where the local pious man would sell the sun with its shine like a pig in a poke, and parents would expose their own daughter to public humiliation because of an indiscretion (whose issue is the angry speaker of the poem). It was as if Halpern were deliberately resharpening the original satiric edge of the 19th-century Yiddish literature, and recalling the restrictive harshness of traditional Jewish society against which the immigrant generation had rebelled.

Paradoxically, though these poems were attacked for their callousness, Halpern’s rough images were a better instrument of commemoration than the pastel reminiscences they mocked. The freshness of his antipathy made the shtetl come artistically alive, endowed its petty villainies with the ring of actuality. It was the elegy that Halpern hated, the hushed respect that comes into being only after its subject has died. In a not unusual poem by Halpern, a man watching a prostitute undress for him is sourly reminded of the way his grandfather used to pull his shirt over his head in the bathhouse, even though he had been given buttoned shirts that could be taken off less dramatically. The introduction here and there of these original, irreverent analogies were small, deliberate acts of sword-crossing within a general literary atmosphere of pious enshrinement.

The provocative nature of Halpern’s verse sometimes obscured its emotional and thematic profundity:

Evening sun.

And, in evening cold, all the flies

In the corners of the panes are numb,

If not already dead.

On the rim of a water glass, the last

Is alone in the whole house.

I speak:

“Dear fly,

Sing something of your far-off land.”

I hear her weep—She answers:

May her right leg wither

If she plucks a harp

By strange waters

Or forgets the dear dung heap

That had once been her homeland.

—(Translated by Nathan Halpern)

Despite the reduction of everything—of the globe and the journey across it, of the poet and his poetic tradition, of the Jewish exile and the eternity of Jewish longing—an unexpected compassion stirs. Diminished, corrupted, and almost extinct, a parody of former grandeur, the Jew and the poet still sing of their yearning. The swollen rhetoric must be deflated by Halpern’s impious effrontery before feeling can once again emerge.

_____________

If the prettification of a national past provoked him to mockery, the denial of contemporary social reality stirred Halpern to even greater rage. He had no consistent, discernible social philosophy, but from the flow of his sympathies and antipathies a line of argument emerges. The acknowledged tyrant over earth’s creatures is the stomach. People, no less than mice, go to great lengths to protect their rations. It is therefore necessary, in any judicious assessment of the human condition, to recognize the daily marketplace scramble for “onions and cucumbers and prunes.” The crudity of this struggle is admittedly disheartening to aesthetes and other idealists. But as long as it remains the basis of life, the primacy of matter over spirit cannot be gainsaid. This is as close as Halpern comes to an outright endorsement of Marxism.

Halpern’s fierce independence precluded any fixed loyalty to system or party. There were times when he blistered like Mayakovsky, hurling insults at the goddamned intellectuals with their white hands and at the cowardly enemies of the great experiment of dictated social equality. His poem on the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, the anarchists whose trial for murder was used by the Communists as a rallying point against the American system, is exceptionally poignant, an expression of genuine outrage. There were also poems like “A Striker Song,” echoing the old sweatshop complaints of oppressed workers against their bloodsucking bosses, which were set to music to be sung at union rallies.

But essentially, Halpern looked up the skirts of every orthodoxy. The Russian Revolution was an accident. “Had Lenin been the father of a child, or better yet of five children, as he was himself one of five, the Czar would still be ruling Russia.” This certainty, based on Halpern’s exceptionally powerful instincts of paternal love and responsibility, gives the lie to historical determinism. Though Halpern enjoyed his reputation as a “proletarian poet,” and took pride that the landlord’s painter, sent in to touch up his apartment, knew of his work, he had no confidence in the proletariat as such, scorning anyone who could make a virtue or accept the harness of steady labor. All absolute claims are comical, whether human or divine. In “The Tale of the World,” a great king ordains the conquest of all the world, only to discover that it is far too large to fit into the royal palace:

The courtiers, meanwhile, hold that the world

Should be kept out there under guard.

But the king has turned a deathly gray,

Fearing the world will get wet some day

When the rain falls hard.

But the plow in the field,

And the cobbler’s leather sole,

And the mouse in his hole,

Laugh till they cry,

Laugh till they nearly die.

The world’s still there, outside.

—(Translated by John Hollander)

Reality defies metaphysical or political systematization, and the spirit most authentically attuned to life must be duly profane.

_____________

Halpern’s resistance to the accepted sentiments and postures of his time comes to sharpest expression on the national question, not so much because of Halpern’s identification as a Jew, which was forever touched by irony, but because of his passionate distrust of the “goyim.” His unkind views of Christians were disturbing to every segment of the Jewish readership: to those with faith in American tolerance who did not want to be reminded of religious divisiveness, and to those preaching the international brotherhood of workers. But for Halpern, the pretense of brotherliness where none existed was a particularly corrupting form of self-deception. It required, first, a falsification of the past; then, a willful stupidity in the present. What is more, it was inevitably accompanied by self-hatred, of which the modern Jew already had more than his fair share.

In his own case, the poet traced his encounter with hostile Christianity back to childhood incidents, such as the special treatment he was accorded by his Polish classmates:

A golden cross was thrust at me to kiss

A second classmate smeared a cross over my

back.

And when my youthful heart could tolerate no

more,

The teacher noted it, and turned me out the

door.

Halpern acknowledges that after this and similar incidents he went out into the world and learned that Jesus brought his blood as a sacrifice to atone for the sins of mankind. But even so, he could not learn to love those pious folk whose faith in Jesus’ blood expresses itself in the pursuit of his.

Eventually Halpern’s intuitive rebellion evolved into a philosophical distaste for Christianity’s justification of suffering and death. Christianity is seen to be doubly deceitful: theoretically, because it falsifies the absolute distinctions between life and death; practically, in its violent exercise of the religion of love. Some of Halpern’s poems poke gentle fun at Christian spirituality, as when Jesus speaks to the children, explaining that all in the world is his—with the single exception of them. Elsewhere, in poems like “The Jewish Blacksmith,” the Christian is the wanton and stupid murderer of the Jew, refusing his civil companionship and repudiating his assistance:

He’s got himself an alehouse where he whoops

it up and drinks

He’s got himself a churchhouse where he suppli-

cates and stinks

And that’s all he needs—that lout, my neighbor.

Appalled by such blunt characterization of European peasantry, the Communists accused Moishe Leib of fomenting pogroms, a charge that seemed only to fuel his attack. His style grew more crabbed, but his aim remained sure:

In the Soviet Union . . . no sooner does the rooster crow than someone must begin worshiping the red divinity, blessed be he, because otherwise no one is allowed to hang around with his hands in the mud—like the Israelites in Egypt. There is only this difference: there, they kneaded children into the walls, whereas in Sovietland you have only to reshape yourself. You become a new Adam—without even a figleaf. For the robust goyim this is surely a piece of good luck, but for our kind . . . well, I’ve heard that they skulk around with their hands over their genitals, more atremble now before the puniest little Gentile than they ever were before.

This was Halpern with his gloves off, striking out in both directions at once. Seeing matters plain, “without even a figleaf,” he recognized under the revolutionary camouflage the persistent hold of despotism and anti-Semitism, and the modern forms of Jewish enslavement and self-enslavement.

_____________

Outside the tiny island of his wife and son, Halpern did not make his peace with very much, least of all with himself. Unfortunately, his reputation as an upstart and rebel itself became something of a cliché, so that even his most attentive readers did not note the deepening strain of pessimism that went along with the increasing difficulty of his later work. The similes and metaphors which had always been an important feature of Halpern’s style began to take on a life of their own, growing homerically, and overshadowing narrative or thematic development. At the same time the poems came to be set out along a line of rational argument, with prepositions and conjunctions—although, because, despite, notwithstanding, but, if only, yet—like so many signposts, pretending to guide the poem to its firm, logical, inevitable conclusion. The tension between the reasoned form of the discourse and the wild density of its images, between the homey, old-world stock of references, and the bleak, modern situation to which they were applied, heightened the anxiety of this poetry, as if it were straining to achieve clarity against an overwhelming emotional tide.

Indeed, there seems little doubt that Halpern was struggling for clarity. To those who told him they could not understand his latest work, he answered with incredulity but tried with rough patience to explain. Many of these poems take the form of exhortations, public lectures, notes of advice to his son, where within the thickets of private allusions he warns against war, mourns poverty, and decries its corresponding evil, petty greed.

But the futility of this effort was also his theme. Halpern had been drawn to Yiddish in a milieu of cultural vitality, when writers were prized, perhaps not with sufficient critical detachment, but personally, for what they represented to particular segments of emerging modern Jewry, and to the emerging image of a modern Jewry with a literature of its own. It was within this nurturing atmosphere of literary relevance that Moishe Leib matured, only to find that he had overshot the mark. His dazzling complexity was lost on his fellow American Jews, who grew plainly pragmatic under the pressure of local and world events.

Who was responsible for this failed opportunity? Halpern saw that the widening gap between the artist and his natural constituency could be attributed to the artist. He made merciless fun of the poets who want “the words they sing to be as delicate as the church carvings of the Middle Ages, and as pure as the yearning of a flutist in the evening.” When he turns to the housepainter sitting beside him in the subway and asks whether this is what he too wants, the man moves nervously away. Halpern speculates that had he asked the painter whether he wanted a hot bath after work, the man would have known how to respond.

Nevertheless, Halpern understood from his own failed experiment as a public poet that however he might frame his questions, he was beyond the reach of the housepainter. Yiddish had developed a high culture at the moment when its speakers were riveted, as never before, to the struggle for survival. In America, the comic impotence of Yiddish before the hegemony of English cast the language into the role of “the little Jew” within Judaism itself. To put one’s faith in Yiddish was to play the fool, to withstand the reality of acculturation. As one of the chief chroniclers of the immigrant marketplace, Halpern knew the revealed helplessness of his language, and with it of his writing. He quotes a fictitious uncle who says that “if he were a diplomat, he would demand that all declarations of war henceforth be issued in Yiddish only. This would fairly guarantee lasting peace in the world.” In the foreground of this self-mocking statement is the powerless Yiddish utterance. In the background, less humorously, are the actual nation-states, with all too much power for their evil ends.

Despite his grim appraisal of the fate of the poet in modern times, of Yiddish among the Jews, and of Jews among the Gentiles, Halpern stayed almost free of self-pity. The energy of his anger and hatred gave wings to his imagination, made him endlessly inventive. Halpern sharpened the teeth of American Yiddish literature. Having cut himself loose from Jewish pieties, he did not seek shelter among any of the alternate orthodoxies, whether aesthetic or political. In a sense his work reflects the energy of the immigrant generation that went out “on its own” with all the impudence and improvisation of those with nothing to lose.

Unlike English writers like Abraham Cahan, whose work undertakes to interpret the Jewish immigrant to the non-Jews, Halpern was unshackled by any external constraint. In him one can find the boldness and self-reliance that was so much in evidence among immigrant Jewish businessmen, but so little manifest in their cultural spokesmen. There are those who found him too aggressive, arguing that his joy in combat ruined the finer judgment required of art. What makes Halpern unusual, even among the aggressive Jewish writers, is that his opposition to others remained appreciably greater than his antagonism toward his own.

_____________

Note

For the English reader, the best examples of Moishe Leib Hal-pern’s poetry can be found in A Treasury of Yiddish Poetry, edited by Irving Howe and Eliezer Greenberg (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1969; Schocken [paper], 1976). The Golden Peacock, edited by Joseph Leftwich (Robert Anscombe & Co., 1939), contains some translations of Halpern by the Canadian poet A.M. Klein. Ruth Whitman’s Anthology of Modern Yiddish Poetry (October House, 1966) includes three poems by Halpern with the Yiddish text and facing translation. Individual poems by Halpern have appeared in COMMENTARY (November 1947, October 1949, and June 1950, translated by Jacob Sloan), and in the Kenyan Review (Winter 1979, translated by Kathryn Hellerstein).

#yiddish#jewish culture#yiddishkeit#language#poetry#yiddish language#yiddish language poetry#literature#history#assimilation#marxism#secularism#secular jewish culture

0 notes

Text

« Dans les bagnes du tsar » de H. Leivick, le chant déchirant des châlits 78682 homes

http://www.78682homes.com/dans-les-bagnes-du-tsar-de-h-leivick-le-chant-dechirant-des-chalits

« Dans les bagnes du tsar » de H. Leivick, le chant déchirant des châlits

Dans un récit qui glace et réchauffe à la fois, un poète russe de langue yiddish, H. Leivick, raconte sa vie carcérale entre 1906 et 1912.

homms2013

#Informationsanté

0 notes

Text

Creating a golem is dangerous business, as versions of the legend increasingly emphasize in the medieval and modern periods. One danger expressed particularly in medieval versions is idolatry. Like Prometheus, the one who creates a golem has in effect claimed the position of God, creator of life. Such hubris must be punished. In its modern versions the focus of the golem legend shifts from parables of creation to fables of destruction. The two modern legends from which most of the others derive date from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In one, Rabbi Elijah Baal Shem of Chem, Poland, brings a golem to life to be his servant and perform household chores. The golem grows bigger each day, so to prevent it from getting too big, once a week the rabbi must return it to clay and start again. One time the Rabbi forgets his routine and lets the golem get too big. When he transforms it back he is engulfed in the mass of lifeless clay and suffocates. One of the morals of this tale has to do with the danger of setting oneself up as master and imposing servitude upon others.

The second and more influential modern version derives from the legend of Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague. Rabbi Loew makes a golem to defend the Jewish community of Prague and attack its persecutors. The golem’s destructive violence, however, proves uncontrollable. It does attack the enemies of the Jews but also begins to kill Jews themselves indiscriminately before the rabbi can finally turn it back to clay. This tale bears certain similarities to common warnings about the dangers of instrumentalization in modern society and of technology run amok, but the golem is more than a parable of how humans are losing control of the world and machines are taking over. It is also about the inevitable blindness of war and violence. In H. Leivick’s Yiddish play, The Golem, for instance, first published in Warsaw in 1921, Rabbi Loew is so intent on revenge against the persecutors of the Jews that even when the Messiah comes with Elijah the Prophet the rabbi turns them away. Now is not their time, he says, now is the time for the golem to bathe our enemies in blood. The violence of revenge and war, however, leads to indiscriminate death. The golem, the monster of war, does not know the friend-enemy distinction. War brings death to all equally. That is the monstrosity of war.

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire, 2004

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: From a 16th-Century Book to a Robot-Assisted Performance, Artists Explore the Legend of the Golem

Miloslav Dvořak, “Le Golem et Rabbi Loew près de Prague” (1951), oil on canvas, 244 x 202 cm (Prague, Židovske Muzeum © Jaroslav Horejc) (all images courtesy of musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme, Paris, unless noted)

Noise-math philosopher Norbert Wiener once aptly compared the old Jewish myth about the golem with cybernetic technology. Viewed through that lens, everything from transhuman artificial life cyborgs to anthropomorphic robots to humanoid androids to posthuman digital avatars bear the mystical mark of an artificial body madly turning on its creator. This oily tale is the oldest narrative about artificial life and is now subject of the exhibition Golem! Avatars d’une légende d’argile at Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme.

The golem was first mentioned in passing as גֹּלֶם in the Bible in Psalm 139:16, but the first golem story was spun by the 16th-century Talmudic scholar Rabbi Loew ben Bezalel. In it, he supposedly used Kabbalistic magic, Hebrew letters, paranormal amulets, or mystical incantations to conjure into existence the Golem of Prague: a colossal figure built from mud or other base materials, who protected the Bohemian Jews of the country from the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II. Though initially a savior, the Golem of Prague eventually became harmful to those he had saved and had to be destroyed. There are myriad subsequent versions of the story, with many variations and contradictions. It is generally agreed that what animated this mystical entity was an inscription either applied to its forehead or slipped under its tongue, and the golem has largely been understood to be an artificial man that is part protector and part monster, but many other differences abound. This specious aspect makes the golem particularly interesting to artists because such contradictory vagueness yields opaque and elusive visual iconography.

Paul Wegener, “Le Golem, comme il vint au monde” (1920) (Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin © succession Paul Wegener)

The legend spread in the late 19th century, popularized by the 1915 novel The Golem by Gustav Meyrink and three movies by Paul Wegener: The Golem (aka The Monster of Fate) (1915), The Golem and the Dancing Girl (1917), and The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920). An essential general reference for the golem-phile is Idel Moshe’s 1990 book Golem: Jewish Magical and Mystical Traditions on the Artificial Anthropoid, published as part of the Judaica: Hermeneutics, Mysticism, and Religion series by the State University of New York Press in Albany. In it, Moshe maintains that the role of the golem concept in Judaism was to confer an exceptional status to the Jewish elite by bestowing them with the capability of supernatural powers deriving from a profound knowledge of the Hebrew language and its magical and mystical values.

I first encountered this titillating thesis mixing creation and destruction at Emily Bilski’s 1988 show Golem! Danger, Deliverance and Art, which she curated for The Jewish Museum in New York City. I still remember seeing Louise Fishman’s fine painting “Golem” (1981) there, and I was disappointed that the plucky street performance artist Kim Jones (aka Mudman) wasn’t included.

Joachim Seinfeld, “Golem” (1999), series of 5 photographs, 39.5 × 40 cm (Prague, Židovske Muzeum © Adagp, Paris)

Lionel Sabatte, “Smile in Dust #1” (2017), dust and wire, 13 x 14 x 11 cm (image courtesy of the artist)

Steve Niles and Dave Wachter, Breath of Bones: A Tale of the Golem (2013) (© Dark Horse Comics)

This show in Paris follows on the heels of the Golem exhibit at The Jewish Museum Berlin. Both venues had the idea for an exhibition on the golem at the same time, and the institutions cooperated on loans and exchanged ideas. The Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme show has 136 works, including paintings, drawings, photographs, cinematic clips, literature, comics, and video games by the likes of Charles Simonds, Boris Aronson, Christian Boltanski, Joachim Seinfeld, Gérard Garouste, Amos Gitaï, R.B. Kitaj, and Eduardo Kac. Animated films included are Jan Svankmajer’s masterful Darkness Light Darkness (1989), Jakob Gautel’s First Material (1999), and David Musgrave’s Studio Golem (2012). But the best dramaturgical presentation is the humanoid robotic metaphor of an awakening of posthumanity in School of Moon (2016), a dance choreographed by Eric Minh Cuong Castaing for the Ballet National of Marseille in conjunction with digital artist Thomas Peyruse and roboticist Sophie Sakka. Their impish portrayal blurs our perception of the human and the nonhuman by mixing ballet dancers with children and anthropoid robots.

Christian Boltanski, “Le Golem” (1988), mixed media, 19 × 11.5 × 27 cm (New York, The Jewish Museum © Adagp, Paris)

Gerard Garouste, “Le Golem” (2011), oil on canvas, 270 × 320 cm (collection de l’artiste © Adagp, Paris)

School of Moon (2016), performance (photo courtesy of the artist)

The show kicks off with a large straightforward illustrative painting by Miloslav Dvořak, “Le Golem et Rabbi Loew près de Prague” (1951) but soon turns weirder with a 1964 Dennis Hopper photograph of the great beatnik Wallace Berman. Berman is known for his underground film Aleph (1956–66), in which he uses Hebrew letters to frame a hypnotic, rapid-fire noise montage into a bit of wonder. Moving on, I was fascinated by an odd printed book page from the Sefer Yetzirah (Book of Creation) (1562), in which Kabbalists, wishing to bring a golem to life, looked for the aid of alphabetic formulae. Other powerful pieces include Lionel Sabatte’s redolent sculpture “Smile in Dust” (2017), Philip Guston’s cartoonish painting of a cuddly Ku Klux Klanner “In Bed” (1971), Anselm Kiefer’s crusty stout block “Rabi Low: Der Golem” (1988–2012), Antony Gormley’s rusty condensed sculpture “Clench” (2013), and Niki de Saint Phalle’s swashbuckling “Maquette pour Le Golem” (1972), her model for the architecturally scaled triple-tongued monster slide “Le Golem” (1972), which she built in Jerusalem, that represents the three monotheistic religions plummeting from a golem-monster’s merry mouth.

Sefer Yetsirah, Mantoue: Livre de la creation (1562), printed book page (detail), 21 × 16 cm (Paris, bibliothèque de l’Alliance israélite universelle)

Philip Guston, “In Bed” (1971), oil on canvas, 128 × 292 cm (Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle, dépôt de la Centre Pompidou Foundation; photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Niki de Saint Phalle, “Maquette pour Le Golem” (1972), plâtre, 64 × 114 × 118 cm (Jerusalem, Israel Museum © 2017 Niki Charitable Art Foundation / Adagp, Paris)

Anselm Kiefer, “Rabi Low: Der Golem” (1988–2012), plastique, bois, plomb, verre, résine synthétique, acier, et charbon de bois, 95 × 95 × 58 cm (Anselm Kiefer, courtesy galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris-Salzbourg)

One of the more delightful displays was the room full of Ignati Nivinski’s 1924 watercolors made for the costumes of the 1925 theatre piece The Golem, on loan from the Russian National Archives of Literature and Art. The play was based on the 1921 text The Golem: A Dramatic Poem in Eight Scenes by H. Leivick, a Yiddish poet and political radical who served jail time in Siberia. On the other hand, I was startled and disturbed to see Walter Jacobi’s distasteful 1942 book Golem, a flagrant anti-Semitic propaganda text concerning a Judeo-Masonic conspiracy theory within the Czech Jewry, issued during the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. Seeing it made me think that a Trump-era cyber-golem would busy himself with public relations, propaganda, market research, publicity, disinformation, counter-facts, censorship, espionage, and even cryptography (which in the 16th century was considered a branch of magic).

Ignati Nivinski, “Esquisse pour les costumes de la pièce Le Golem de H. Leivick” (1925), crayon, aquarelle, tempera sur papier, 23 × 15 cm (Moscou, Archives nationales russes de littérature et d’art)

Walter Jacobi, Golem (1942), photo by the author

The show winds down wonderfully with Walter Schulze-Mittendorff’s sculpture “Robot from Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis” (1926), which was recreated by the Louvre in 1994, standing in front of Stelarc’s “Handwriting: Writing One Word Simultaneously with Three Hands” (1982). The combination of these works suggests that golems have to do with an abiding conviction that cold and inert matter may be brought to life through the correct application of words. But rather than a sign of human accomplishment, the golem casts a sour shadow onto our gleaming technological age. The power of human language to summon golems to artificial life is experienced as hubris in this exhibit. This vanity enhances the sexy love-hate of spooky computer-robotics we feel at the root of Alex Garland’s 2015 film Ex Machina, a poster for which is on display. We cannot and do not escape the triumphal attraction of the golem here, as we are confronted (again) with the fetid fact that a determinative force in human life is the virtual merging with the actual. As such, the golem is the minotaur at the heart of our viractual labyrinth.

Stelarc, “Handwriting: Writing One Word Simultaneously with Three Hands at Maki Gallery, Tokyo” (1982) (photographed by Keisuke Oki; re-photographed by the author)

Golem! Avatars d’une légende d’argile, installation view

This brave new word-world was suggested back in 1965 by Kabbalah philosopher Gershom Scholem, when he officially named one of the first Israeli computers Golem I. Because just as the golem is brought to life by combinations of letters, the computer (which is behind any artificially intelligent robot) only obeys coding language. And that coded situation slots us back into Norbert Wiener’s excited trepidation toward machine learning. While learning is a property almost exclusively ascribed to self-conscious living systems, AI computers now exist that can learn from past experiences and so improve their operative functions to the point of surpassing human capabilities. This posthuman transcendence raises concerns both aesthetic and ethical, casting around the art in this show an apologetic air heavy with ambivalence toward human cunning and trickery and seductive art and technology.

Golem! Avatars d’une légende d’argile continues at Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme (Hôtel de Saint-Aignan, 71, rue du Temple, 3rd arrondissement) through July 16.

The post From a 16th-Century Book to a Robot-Assisted Performance, Artists Explore the Legend of the Golem appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2qBC9fA

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

They are Delmore Schwartz’s Elisha ben Abuya (the American Marrano Faust, the Repentant Heretic, the Informer) and H. Leivick’s Elijah (the Fallen Prophet as the uncanny, the Rejected Messiah translated into a weapon). TO ME

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Tis a dark and stormy night, so it’s best to watch out for werewolf...rabbis?

Yes, indeed. If you thought Yiddish folklore was all about explaining the guilty verdict of history and how it’s best to swallow the bitter pill, because you can only chase it down with a bitterer draft, well, you were mostly right. But if you also thought that tucked in the pages of my new collection of Yiddish folk tales, parables, scoldings, and resignation is the best psychological horror yarn no one knew existed, you were also right.

Behold, H. Leivick’s “The Wolf,” the precursor to the greatest Jewish terror-comic film of all time, An American Werewolf in London. (Of course, that might be the only Jewish terror-comic film, but if you don’t think my post-Holocaust shlock as shock therapy theory is valid, you can test it on those dream sequences.) Leivick, fugitive from Mother Russia, is no stranger to tackling creature feature; his play, The Golem, somehow turns a scary story about a clay man into a Miltonian epic with messianic ruminations and introspective soliloquies where every man, even the clay one, verges on tragedy. “The Wolf” stalks in the same vein, when a rabbi, last survivor of anti-Semitic violence, finds himself transformed into the titular beast. And if you think Leivick seizes the opportunity to inflict on us some good old-fashioned revenge fantasy, you couldn’t be more wrong. Oh, the wolf turns deadly, but in a way that reminds us the cost of the fantasy. More chilling than any teeth-and-claw bloodhunt could ever be.

#H. Leivick#a nice jewish tag#book club#who knew there was such a tradition#no wonder I always liked Lupin#but yes#I would consider Yiddish folk tales to be a nice companion to the Grimm fairy tales#one warns you not to venture into the woods#the other warns you that people are going to accuse you of snatching the wandering child and baking it into bread#charming

3 notes

·

View notes