#inspired certain policies in Apartheid in South Africa

Text

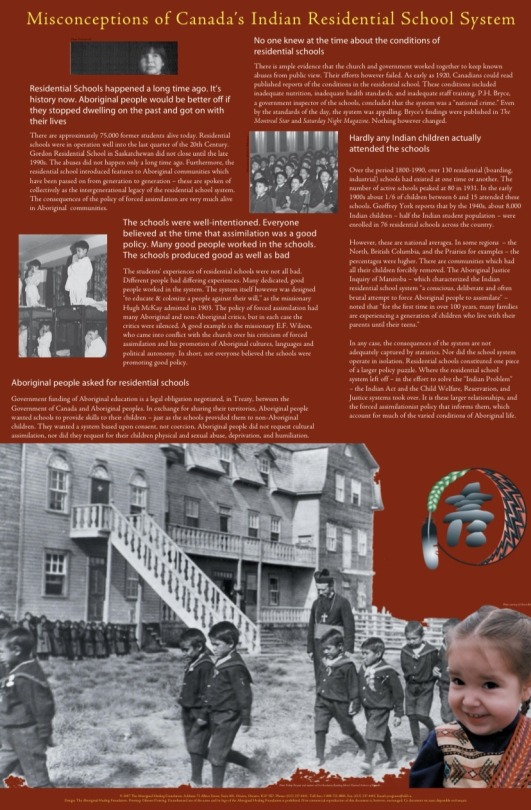

It’s Orange Shirt Day here in Canada (more formally called the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation) so I thought I’d share this page of common misconceptions about Residential Schools that one of my Indigenous Studies Professors shared with my class. (Click on the image for better quality)

One place you can read more about Survivors stories is in The Survivors Speak Report

#orange shirt day#residential schools#no matter where in the world you’re from I think this is really important to learn about#i learned that government policies enforced on Indigenous people in Canada#inspired certain policies in Apartheid in South Africa#the oppression of peoples all over the world is more linked than we realize

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacinda Ardern and Compassionate Leadership

Jacinda Ardern's legacy as a compassionate leader is defined by her empathetic approach to governance and her ongoing commitment to fostering an environment of inclusivity, kindness, and social justice. As the Prime Minister of New Zealand, she exemplified compassionate leadership through her response to crises such as the Christchurch mosque shootings as well as the COVID-19 pandemic. Ardern's emphasis on unity, empathy, and support for marginalized communities has earned her widespread admiration both domestically and internationally, so much so that she is often referenced when speaking of American politics as the type of politician we need more of. She has implemented policies aimed at reducing child poverty, addressing climate change, and promoting mental health and well-being. Jacinda Ardern's leadership style has redefined what it means to lead with compassion in the modern era, and she has set a precedent to how leaders around the world should prioritize the well-being of their constituents above all else.

I think I would define compassionate leadership as hearing from your constituents/citizens and responding to all of them with empathy, even when (undoubtedly) you’ll be making some percentage of them upset. With that said, as much as I want power and empathy to coexist and work hand-in-hand, I feel that it has been shown that, time and time again, when a certain amount of power is reacher, empathy starts to get ignored. I think some part of that is unchecked power allowing people in power to do as they please and have a complete disregard for empathy and the feelings of others.

I think the world needs a more diverse collection of leaders in general. I think having a bunch of loud voices from only one group inhibits any amount of growth within a society and also inherently makes some people feel less powerful. I think if more women or people of color start to have louder voices and start to be the lawmakers, we will see more just laws just because there are so many more expires and perspectives in that collection of voices.

“I greet you all in the name of peace, democracy and freedom for all. I stand here before you not as a prophet, but as a humble servant of you, the people. Your tireless and heroic sacrifices have made it possible for me to be here today. I therefore place the remaining years of my life in your hands.” -Nelson Mandela, 1990

Nelson Mandela's legacy is a true testament to how empathy and selflessness have immense power when it comes to redefining notions of leadership and compassion. Mandela’s unwavering commitment to justice, equality, and reconciliation between the people of South Africa not only catalyzed the dismantling of the apartheid regime, but also had a lasting effect across the globe, inspiring countless other activists and movements. Mandela's ability to extend empathy even to those who had oppressed him exemplified a profound understanding of the interconnectedness of humanity and, through that, how empathy can lead someone into the good graces of not only their nation but the world. Nelson Mandela’s enduring legacy serves as a beacon of hope as well as a lesson, reminding us all of the potential for compassion to foster meaningful change on a global scale.

0 notes

Text

Palestine is about to be annexed by Israel and we should do something

The Netanyahu government is planning to start the annexation of about 30% of the West Bank from July 1st. This is a violation of international law, coming after years of violations by building settlements on the West Bank. The area Netanyahu has his eyes on has a high concentration of settlements. On top of that the government also plans to take the Jordan Valley. The annexation would further fracture Palestinian areas, which makes a future two-state solution ever more difficult.

Downsides to annexation:

- building settlements becomes easier and more attractive (because annexation officially puts settlements under Israeli sovereignty)

- claiming areas for settlements is often accompanied by land expropriation or destruction of Palestinian civilians’ homes

- settlements are accompanied by separate roads and Palestinians are often not allowed to pass through settlements (or it takes a lot of time to pass humiliating checkpoints). This is a problem because it splinters the West Bank into a patchwork of enclaves. Because Palestinians have to use worse, separate roads moving around the settlements, towns can go from being 10 minutes apart to being an hour apart.

- violent encounters between settlements and Palestinian towns are likely to increase. Peaceful demonstrations are also frequently met with harsh military violence, even against children.

- it becomes more difficult to reach a two-state solution as the Palestinian part of the West Bank shrinks further and further down and is splintered by settlements.

- it will almost certainly exacerbate tensions

- if we allow this to happen, that could well be interpreted as permission to take more land in the future, until the entire West Bank is annexed and the two state solution utterly lost. All Palestinians there would end up living in a state of apartheid.

Sources to read more in detail:

https://edition.cnn.com/2020/06/12/opinions/israel-has-a-lot-to-lose-by-annexing-west-bank-territory-satloff/index.html

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-52756427

https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=258664238754275&ref=watch_permalink (long discussion)

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/11/israels-annexation-of-the-west-bank-will-be-yet-another-tragedy-for-palestinians

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/06/explainer-israel-annexation-plan-occupied-west-bank-200627085214900.html

WHAT YOU CAN DO

By all means skip to your country or Everyone at the bottom

United States

I don’t see the US imposing any sanctions on Israel in the next four years to be honest, not now that Bernie Sanders is out of the race. That being said, there’s still a lot to be gained. Under Trump, the US is extremely pro-Zionist, to the point of being a deterrent to other countries. Under Biden, it could at least be more of a neutral than an actively harmful factor. Therefore:

Fucking vote for Biden in November even if you hate the guy, because in almost any policy area he’s better than Trump. You can’t self-righteously abstain from voting, it’ll just put some specks of actual blood on your hands.

Also consider calling your representatives, especially Democrats, because even among them there’s a lot of sympathy for the expansionary ambitions of the Israeli right-wing and reluctance to stand up for Palestinian human rights. Let them know that you care, because the evangelical lobby certainly does.

What to ask:

- for support for sanctions in the future

- for recognition of Palestine as a state

- for conditional aid to Israel in the future (conditional on the end of settlement building)

- for aid to the Palestinians, especially in the Gaza Strip

- for voting in the UN Security Council on the issue to be guided by international law

European Union countries

The EU is a special case because it cannot impose sanctions unless all member states unanimously agree, which is nearly impossible on this issue. However, the Irish attempted to ban products from the settlements, which could be in line with EU law. (It’s called the Occupied Territories Bill.) The government has dropped that idea recently, but please if you are from Ireland, let your voice be heard that this plan should be revived. If your country is already quite critical of the annexation, consider advocating for similar legislation to be drafted in calls or emails to politicians.

If you live in a right-wing country with close ties to Israel at the moment, please advocate for your government not to block measures against the annexation in the EU. The assumption is that the population is pro-Zionist. Make it clear that there are many who oppose expansionism and human rights violations.

In any country that hasn’t already done so: demand the recognition of Palestine as a state. This can be done without a European consensus.

In pro-Palestinian or ‘neutral’ countries: advocate for new trade agreements and partnerships with Israel to be conditional on the end to settlement policies and annexation.

Other countries

- call your representatives or send them a letter/email demanding the imposition of sanctions if the Netanyahu government follows through with the annexation.

- demand the recognition of Palestine as a state if your country hasn’t already done so (many of ya’ll non-Western countries have, props to you!)

- demand the freezing of trade agreements / partnerships if annexation takes place.

Everyone

organise locally churches, campuses, and trade unions are key allies to Palestine. Try bringing up the topic in any organisation of which you’re a member.

take Palestine into consideration in elections at least most European parties have a position on this issue somewhere on their website. Look it up next election season and take it into account when you vote.

volunteer for local pro-Palestine charities there are many and they need you. Many of them collect money for especially Gaza, which desperately needs medicine, clean water, and food. They also provide information to swing public opinion, as well as talking to politicians. Your city probably has one that you don’t know of.

defend all human rights a frequent criticism levied at those standing up for Palestine is that they’re harsher on Israel than other countries. Therefore, and also because you’re a decent human being, stand up for all human rights issues where you encounter them.

take part in direct action this includes only peaceful demonstrations. DO NOT TAKE PART IN ANY VIOLENT ACTION, ESPECIALLY NOT AGAINST JEWISH ORGANISATIONS OR PEOPLE. Moreover, do not levy your critique of the Israeli government at Jewish people or organisations AT ALL. Not a single Jewish person is accountable for Israel’s actions.

parttake in BDS (very much optional) BDS involves the boycotting, divestment from, and imposition of sanctions against Israel until it ends its occupation of the Palestinian territories, the West Bank and Gaza. The idea if best explained on the website, but the basic idea is inspired by the anti-apartheid movement against South Africa. It is not meant as a punishment, but as a coercive measure that will end the moment the occupation does. You can take part by not buying from certain companies supporting the settlements (see Google), not travelling to Israel, or avoiding Israeli / settlement products in the store (the latter should be labelled in the EU (soon)). The extent to which you want to boycott is up to you, and I will admit that sanctions are a contested policy measure.

donate to pro-Palestinian organisations

national / local ones

Jewish Voice for Peace: https://secure.everyaction.com/b5-NLp5380at34y9v7fS5Q2?am={{LastContributionAmount%20or%20%2750%27}}?ms=link

Breaking the Silence: https://www.breakingthesilence.org.il/

https://bdsmovement.net/donate

http://adalah.org/eng/

http://www.alhaq.org/about-al-haq/about-al-haq

http://www.mezan.org/en/

http://www.btselem.org/about_btselem/contact_us

http://www.thefreedomtheatre.org/

http://www.justvision.org/

http://www.alternativenews.org/english/

http://cfpeace.org/

http://www.newprofile.org/english/

http://www.theparentscircle.com/

sign petitions

UK https://palestinecampaign.eaction.online/stopannexation

Everyone https://www.theotherjerusalem.org/petition

US https://www.change.org/p/u-s-senate-oppose-annexation-of-palestinian-land

Norway https://www.change.org/p/israeli-ambassador-to-oslo-stop-israeli-west-bank-annexation-sign-the-petition?source_location=topic_page

US https://sign.moveon.org/petitions/congress-dont-endorse

Belgium http://www.stop-occupation.be/

There are wayyyyy more of them! Please look them up in your own language / country, relevant to where your country stands on the issue, and post a link when you reblog <3

signal boost this post and others like it

educate yourself, educate your friends, family, classmates, those at your place of worship, colleagues, any strangers who will listen but be kind, always

#palestine#israel#signal boost#news#global events#world events#politics#international politics#occupation#palestinians#annexation#political#benjamin netanyahu#netanyahu#palestina#israeli politics#BDS#ilhan omar#us politics#Donald Trump#israeli-palestinian conflict#palestine israel#west bank#gaza#jerusalem#zionism

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is The Definition Of Republicanism

New Post has been published on https://www.patriotsnet.com/what-is-the-definition-of-republicanism/

What Is The Definition Of Republicanism

Democracy’s Discontent: America In Search Of A Public Philosophy

In this book, Sandel contrasts the tradition of civic republicanism with that of procedural liberalism in the US political history. The presentation is organized as the intertwining of philosophical and mostly historical analyses. Philosophically, based on LLJ, Sandel continuous his criticism of liberalism and argues for the idea of civic republicanism with the sense of multiply situated selves. Historically, Sandel shows, while both procedural liberalism and civic republicanism used to be present throughout American politics, American political discourse, in the recent decades, has become dominated by procedural liberalism, and has steadily crowded out the republican understandings of citizenship, which is important for self-government.

Sandel reminds us that the American Revolution was originally aspiring to generate a new community of common good. By separating from England, Americans attempt to stave off corruption and to realize republican ideals, to “renew the moral spirit that suited Americans to republican government” . Unfortunately, in the years following independence, leading politicians and writers started to worry the corruption of the public spirit by the rampant pursuit of luxury and self-interest. Nowadays, most of American practices and institutions have thoroughly embodied the philosophy of procedural liberalism. Despite its philosophical problem, it has offered the public philosophy by which Americans live.

Republicanism In The Thirteen British Colonies In North America

Republicanism in the United States

In recent years a debate has developed over the role of republicanism in the American Revolution and in the British radicalism of the 18th century. For many decades the consensus was that liberalism, especially that of John Locke, was paramount and that republicanism had a distinctly secondary role.

The new interpretations were pioneered by J.G.A. Pocock, who argued in The Machiavellian Moment that, at least in the early 18th century, republican ideas were just as important as liberal ones. Pocock’s view is now widely accepted.Bernard Bailyn and Gordon Wood pioneered the argument that the American founding fathers were more influenced by republicanism than they were by liberalism. Cornell University professor Isaac Kramnick, on the other hand, argues that Americans have always been highly individualistic and therefore Lockean.Joyce Appleby has argued similarly for the Lockean influence on America.

In the decades before the American Revolution , the intellectual and political leaders of the colonies studied history intently, looking for models of good government. They especially followed the development of republican ideas in England. Pocock explained the intellectual sources in America:

The commitment of most Americans to these republican values made the American Revolution inevitable. Britain was increasingly seen as corrupt and hostile to republicanism, and as a threat to the established liberties the Americans enjoyed.

Basic Principles Of Republican Government In The United States

The republican government in the United States has a few basic principles:

The power and authority of government comes from the people, not some supreme authority, or king.

The rights of the people are protected by a written constitution and through the vote of the people.

The citizens give power to elected representatives, based on majority rule, to serve their interests and act on their behalf.

The representatives are responsible for helping all the people in the country, not just a few people.

The stability of government rests with the people and is dependent on civic involvement.

The Constitutive Notion Of Civic Republicanism: Pettit

Insofar as republican freedom is tied to power, it is essentially egalitarian. It is held to protect each individual against arbitrary power, and also to be a ‘communitarian good,’ allowing people to identify with a state that protects their freedom. This version of republican freedom is heavily influenced by Rousseau, purged of totalitarian accretions, and updated to the advanced capitalist societies of the late twentieth century. They are now explicitly inclusive, bestowing their benefits on all members of society, and also multicultural, displaying liberal neutrality toward different substantive conceptions of the good. How far such societies can provide a stable balance between the participatory core of republican freedom and the centrifugal drives of modern pluralism remains to be seen.

Andrew Tsz Wan Hung, inInternational Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences , 2015

Understand The Factions Of Conservative Republicans

Understand the factions of conservative republicans. Conservative republicans are broken into different groups, based on the policy or issue at hand. A person might not be conservative on all issues, but is still considered a conservative republican based on his or her beliefs and practices in one certain area.

The British Empire And The Commonwealth Of Nations

In some countries of the British Empire, later the Commonwealth of Nations, republicanism has taken a variety of forms.

In Barbados, the government gave the promise of a referendum on becoming a republic in August 2008, but it was postponed due to the change of government in the 2008 election. A plan to becoming a republic was still in place in September 2020, according to the current PM, with a target date of late 2021.

In South Africa, republicanism in the 1960s was identified with the supporters of apartheid, who resented British interference in their treatment of the country’s black population.

Republicanism in Australia

In Australia, the debate between republicans and monarchists is still active, and republicanism draws support from across the political spectrum. Former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull was a leading proponent of an Australian republic prior to joining the centre-right Liberal Party, and led the pro-republic campaign during the failed 1999 Australian republic referendum. After becoming Prime Minister in 2015, he confirmed he still supports a republic, but stated that the issue should wait until after the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. The centre-left Labor Party officially supports the abolition of the monarchy and another referendum on the issue.

Republicanism in BarbadosRepublicanism in the NetherlandsRepublicanism in Spain

Which Republican President Inspired The Teddy Bear

Theodore Roosevelt, a Republican U.S. president from 1901 to 1909, inspired the teddy bear when he refused to shoot a tied-up bear on a hunting trip. The story reached toy maker Morris Michtom, who decided to make stuffed bears as a dedication to Roosevelt. The name comes from Roosevelt’s nickname, Teddy.

See all videos for this article

Republican Party, byname Grand Old Party , in the United States, one of the two major political parties, the other being the Democratic Party. During the 19th century the Republican Party stood against the extension of slavery to the country’s new territories and, ultimately, for slavery’s complete abolition. During the 20th and 21st centuries the party came to be associated with laissez-fairecapitalism, low taxes, and conservative social policies. The party acquired the acronym GOP, widely understood as “Grand Old Party,” in the 1870s. The party’s official logo, the elephant, is derived from a cartoon by Thomas Nast and also dates from the 1870s.

Identify And Believe Like The Fiscal Conservatives

Identify and believe like the fiscal conservatives. The fiscal conservatives are based around money and government. They want the government to be smaller and to reduce its spending. The government will have less power over the people. The national debt will be repaid. Fiscal republicans are also for privatizing social security.

What Defined Republicanism As A Social Philosophy

What defined republicanism as a social philosophy? Citizenship within a republic meant accepting certain rights and responsibilities as well as cultivating virtuous behavior. This philosophy was based on the notion that the success or failure of the republic depended upon the virtue or corruption of its citizens.

Republicanism In The United States Facts For Kids

Kids Encyclopedia FactsRepublican Party republicRoman Republicelectedappointedvetoeschecks and balances

Republicanism in the United States is a set of ideas that guides the government and politics. These ideas have shaped the government, and the way people in the United States think about politics, since the American Revolution.

The American Revolution, the Declaration of Independence , the Constitution , and even the Gettysburg Address were based on ideas from American republicanism.

“Republicanism” comes from the word “republic.” However, they are not the same thing. A republic is a type of government . Republicanism is an ideology – set of beliefs that people in a republic have about what is most important to them.

What Is The Definition Of Republican Government

The adjective republican describes a government made up of representatives who are elected by the citizens. If you live in the United States, you’re part of a republican system of government. In a republican government, citizens have a lot of power — their vote determines who is running the government.

So Is The United States A Democracy Or Republic

For all practical purposes, it’s both. In everyday speech and writing, you can safely refer to the US as a democracy or a republic. If you want or need to be more precise in referring to the system of the US, you can accurately call it a representative democracy. And should you need to be exacting? The US can be called a federal presidential constitutional republic or a constitutionalfederal representative democracy.

What you should take away in the confusion over democracy vs. republic is that, in both forms of government, power ultimately lies with the people who are able to vote. If you are eligible to vote—vote. It’s what, well, makes true democracies and republics.

Exercise that right to vote, whether by mail or in person. Want more information on what mail-in voting means? Read our article on absentee vs. mail-in ballots!

*

What Does Republicanism Mean In Your Own Words

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic with an emphasis on liberty and the civic virtue practiced by citizens. More broadly, it refers to a political system that protects liberty, especially by incorporating a rule of law that cannot be arbitrarily ignored by the government.

Is The United States A Republic Or A Democracy

The following statement is often used to define the United States’ system of government: “The United States is a republic, not a democracy.” This statement suggests that the concepts and characteristics of republics and democracies can never coexist in a single form of government. However, this is rarely the case. As in the United States, most republics function as blended “representational democracies” featuring a democracy’s political powers of the majority tempered by a republic’s system of checks and balances enforced by a constitution that protects the minority from the majority.

To say that the United States is strictly a democracy suggests that the minority is completely unprotected from the will of the majority, which is not correct.

What Is The Best Definition Of Republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. … Republicanism may also refer to the non-ideological scientific approach to politics and governance.

Democracy Vs Republic: Is There A Difference

You probably hear countries like the United States or France referred to as democracies. At the same time, you probably also hear both of these countries called republics. Is that possible? Are democracies and republics the same thing or different?

We don’t blame you for confusing these two terms. With a major and heated US election underway, it’s the perfect time for some Government 101. Let’s brush up on these two words to see what they have in common—and what sets them apart.

Constitutional Republic Example In Obamacare

There are several examples of constitutional republic being under attack through lawsuits. These types of situations typically arise when the majority passes a law through their representatives, yet other citizens claim the law is unconstitutional. Perhaps one of the most prominent examples of this in recent history is the challenging of the Affordable Care Act at the Supreme Court level.

Congress passed the Affordable Care Act , which went into effect in March, 2010. The purpose of the ACA was to provide health insurance to millions of Americans who were not covered. It also sought to limit the extent to which citizens could seek health care services for which they could not – or did not – pay.

Shortly after the ACA was passed, several states and organizations – led by the state of Florida – brought lawsuits before the United States District Court in Florida, claiming that the ACA was unconstitutional. Individuals Kaj Ahburg and Mary Brown also jumped on board as plaintiffs in the case.

The group’s claims were based on a number of grounds, among them was the claim that the requirement for employers to purchase health insurance for their employees interfered with state sovereignty, or the right of the state to remain independent and have control over its own decisions.

Constitutional Monarchs And Upper Chambers

Some countries turned powerful monarchs into constitutional ones with limited, or eventually merely symbolic, powers. Often the monarchy was abolished along with the aristocratic system, whether or not they were replaced with democratic institutions . In Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Papua New Guinea, and some other countries the monarch, or its representative, is given supreme executive power, but by convention acts only on the advice of his or her ministers. Many nations had elite upper houses of legislatures, the members of which often had lifetime tenure, but eventually these houses lost much power , or else became elective and remained powerful.

What Is A Republican Republican Definition

April 11, 2014 By RepublicanViews.org

This article fully answers what a Republican is and gives the definition of a Republican in a fair, unbiased, and well-researched way. To start the article we list out the definition of a Republican, then we cover the Republican Party’s core beliefs, then we list out the Republican Party’s beliefs on all the major issues.

The Definition of a Republican: a member of the Republican party of the U.S.

Classical Republicanism And Natural Rights

Classical republicanism promoted the natural rights philosophy, which is echoed in the Declaration of Independence. Natural rights are those rights that are not dependent on, nor can they be changed by, manmade laws, cultural customs, or the beliefs of any culture or government. These rights include such things as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Other natural rights include the right to protect oneself from physical harm, the right to worship as one chooses, the right to express oneself, among others.

The reason why classical republicanism is so prevalent in the Declaration of Independence is because of the colonists’ recognition of the fact that they wanted their government to be vastly different from that of the British parliament. They believed that they were following their civic duty by separating from Britain for the purposes of preserving the “common good.”

Republican Liberty: Problems And Debates

The appeal of the republican conception of political liberty asindependence from the arbitrary power of a master is perhapsunderstandable. This is not to say, however, that this conception isuncontroversial. Before discussing its role in developing contemporarycivic republican arguments, we should consider various problems anddebates surrounding the republican idea of freedom.

What Is The Best Example Of An Oligarchy

Examples of a historical oligarchies are Sparta and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. A modern example of oligarchy could be seen in South Africa during the 20th century. Here, the basic characteristics of oligarchy are particularly easy to observe, since the South African form of oligarchy was based on race.

What Does The Republican Party Stand For

The Republican Party was initially created to advocate for a free-market economy that countered the Democratic Party’s agrarian leanings and support of slave labour. In recent history, the Republicans have been affiliated with reducing taxes to stimulate the economy, deregulation, and conservative social values.

Examples Of Republicanism In A Sentence

republicanism CNNrepublicanismThe New Republicrepublicanism WSJrepublicanismCNNrepublicanism WSJrepublicanismThe New York Review of Booksrepublicanism The New York Review of BooksrepublicanismThe New York Review of Books

These example sentences are selected automatically from various online news sources to reflect current usage of the word ‘republicanism.’ Views expressed in the examples do not represent the opinion of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback.

What Is The Idea Of Republicanism Apush

the ideology of governing the nation as a republic, where the head of state is not appointed through hereditary means, but usually through an election , A philosophy of limited government with elected representatives serving at the will of the people. The government is based on consent of the governed.

Political Liberty Positive And Negative

It is notorious that there are several competing conceptions ofpolitical liberty. The now standard account was laid down mostinfluentially by Isaiah Berlin in his famous lecture on “TwoConcepts of Liberty” . According to the first,‘negative’ conception of liberty, people are free simply tothe extent that their choices are not interfered with. There are manyvariations on this conception, depending on how exactly one wants todefine ‘interference’, but they all have in common thebasic intuition that to be free is, more or less, to be left alone todo whatever one chooses. This idea of negative liberty Berlinassociates especially with the classic English political philosophersHobbes, Bentham, and J. S. Mill, and it is today probably the dominantconception of liberty, particularly among contemporary Anglo-Americanphilosophers. In Mill’s well-known words, “the only freedomwhich deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our ownway, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs”.

The troubling implications of the positive conception of liberty arewell-known, and need not be rehearsed at length here. For the most part, thesestem from the problem that freedom in the positive sense would seem tolicense fairly extensive coercion on behalf of individuals’allegedly ‘real’ interests—for example, coercivelyforcing the gambler to quit on the presumption that this is, in fact,what he really wants to do . Regardingthis danger, Berlin writes:

Republicanism Law And Legal Definition

Republicanism is the imaginary or visionary theorization of governing a nation as a republic. It refers to a form of government where the head of state is appointed for a specific period by means of elections. These leaders, rather than a select aristocracy make laws for the benefit of the entire republic. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context. However, in an ideal republic, head of the state are selected from among the working people; they serve the republic for a defined period, and then return to their work. The key conceptions of republicanism includes the importance of civic virtue, the benefits of universal political participation, the dangers of corruption, the necessity of separate powers and a healthy attitude for the rule of law.

The equality of the rights of citizens is a principle of republicanism. Every republican government is in duty bound to protect all its citizens in the enjoyment of this principle, if within its power. The duty was originally assumed by the States, and it still remains there..

Republicanism Example In Rhode Island

An example of republicanism disputes involved the state of Rhode Island, and came about in 1841. At that time, Rhode Island’s government was still operating under the outdated terms established in 1663 by a royal charter. This charter placed a strict restriction on who was allowed to vote, and didn’t allow for amendments to the law. Groups who were protesting the charter held a convention to enforce the drafting of a new constitution, as well as to overthrow the state government and elect a governor. This movement was known as the “Dorr Rebellion.”

The rebellion started off as a peaceful political protest, but it ultimately turned violent. As a result, the old charter government declared martial law for the area, meaning that a temporary law was imposed and enforced by military forces. Martial law is typically only imposed when the civilian government has been declared broken, or during times of civil unrest.

The state legislature required that federal troops be dispatched to the area to break up the rebellion, but President John Tyler ultimately decided not to send the soldiers in because he felt that the threat of domestic violence was fading significantly as time went on. The rebellion was squashed when Dorr decided to disband the group, after realizing that he would ultimately be defeated in battle by the approaching militia.

Republican Freedom And The Human Good

So far we have assumed that, however ultimately defined, republicanfreedom is always a good thing. Some have wondered whether this is thecase, however. This objection is most often expressed via the exampleof benevolent care-giving relationships. On the republican view thatone enjoys freedom only to the extent that one is independent fromarbitrary power, it would seem that children do not enjoy republicanfreedom with respect to their parents. But surely, one might suppose,the parent-child relationship is an extremely valuableone, and so we would not want greater republican freedom in such acontext. Republican freedom is, perhaps, not always a good thing.

What Is Republicanism In Simple Terms

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic with an emphasis on liberty and the civic virtue practiced by citizens. … More broadly, it refers to a political system that protects liberty, especially by incorporating a rule of law that cannot be arbitrarily ignored by the government.

What Is The Significance Of Oligarchy

The people in this group do not have to be related and their power is most often based on wealth and/or power. The significance of an oligarchy is that these people are only able to get what they want through the formation of an oligarchy and these people hold absolute and unchallengeable authority.

Definition Of A Republican Government

I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the republic for which it stands… Most Americans grew up reciting the Pledge of Allegiance in school, but just what is a republic?

The word republic, comes from the Latin res publica, or public thing, and refers to a form of government where the citizens act for their own benefit rather than for the benefit of a ruler or king. A republican government is one in which the political authority comes from the people. In the United States, power is given to the government by its citizens as written in the U.S. Constitution and through its elected representatives.

Belief in republicanism helped bring about the American Revolution and the United States Constitution. The American colonists were influenced by the writings of Thomas Paine. In his 50-page pamphlet Common Sense, written in 1776, Paine made the argument for political independence from Britain, a representative government, and a written constitution for the colonies. Paine felt the monarch had no place in government and that the people themselves were the legitimate authority for government.

An error occurred trying to load this video.

Try refreshing the page, or contact customer support.

Advantages Of A Republican Government

Have you ever given up your own interests to do something that is good for everyone? In a republican government, selfish interests are given up for the common good of the country. Let’s take a look at more advantages of a republican government.

Laws made by elected representatives are meant to be fair. If people find laws unfair, they can elect other leaders who can change those laws.

A republic allows greater freedom and prosperity. Economic pursuit benefits the entire nation and people are able to live well.

When government serves the interests of the entire country, we say it is serving the common welfare.

There is wider participation in the political process. According to the Declaration of Independence, all men are created equal; therefore, it did not matter if you were a small farmer or a powerful aristocrat. Ordinary people are welcome to participate in government.

Leaders emerge based on people’s talents, not their birthright.

Civic virtue is promoted. Civic virtue includes demonstrating civic knowledge , self-restraint, self-assertion, and self-reliance.

Change and reform come about by vote, not by force.

Attributes Of A Republican Government

Power and authority in the government come from the people

Rights of the citizens are protected through a constitution and voting

Power is distributed to representatives based on majority rule

Representatives are responsible for helping everyone in the country and not just a few people

The involvement of people in the government is what guarantees government stability

Rulers are chosen for their skills and do not gain power based on birthright

Civilians participate in the government processes

The country’s economic pursuits benefit the whole nation

Examples Of Republican In A Sentence

RepublicanRepublicansRepublican Partyrepublicanrepublicans National Reviewrepublican NBC Newsrepublicans NBC Newsrepublicans BostonGlobe.comrepublicansNBC Newsrepublicans WSJrepublicans The Economistrepublicans Indianapolis Starrepublican The New Republicrepublican The Economistrepublican Bloomberg.comrepublican The Atlanticrepublican Harper’s BAZAARrepublican BostonGlobe.comrepublican The New Republicrepublican BostonGlobe.com

These example sentences are selected automatically from various online news sources to reflect current usage of the word ‘republican.’ Views expressed in the examples do not represent the opinion of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback.

Key Takeaways: Republic Vs Democracy

Republics and democracies both provide a political system in which citizens are represented by elected officials who are sworn to protect their interests.

In a pure democracy, laws are made directly by the voting majority leaving the rights of the minority largely unprotected.

In a republic, laws are made by representatives chosen by the people and must comply with a constitution that specifically protects the rights of the minority from the will of the majority.

The United States, while basically a republic, is best described as a “representative democracy.”

In a republic, an official set of fundamental laws, like the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights, prohibits the government from limiting or taking away certain “inalienable” rights of the people, even if that government was freely chosen by a majority of the people. In a pure democracy, the voting majority has almost limitless power over the minority.

The United States, like most modern nations, is neither a pure republic nor a pure democracy. Instead, it is a hybrid democratic republic.

The main difference between a democracy and a republic is the extent to which the people control the process of making laws under each form of government.

Founding Father James Madison may have best described the difference between a democracy and a republic:

Constitutional Republic Vs Democracy

Some believe that the United States is a democracy, but it is actually the perfect example of a constitutional republic. A pure democracy would be a form of government in which the leaders, while elected by the people, are not constrained by a constitution as to its actions. In a republic, however, elected officials cannot take away or violate certain rights of the people. The Pledge of Allegiance, which was written in 1892 and adopted by Congress in 1942 as the official pledge, even makes reference to the fact that the U.S. is a republic:

“I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic, for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

The Anti-Federalists and Federalists, as the new nation was being formed, could not agree on how involved the federal government should be in citizens’ lives; a decision on a pure democracy could never be reached. Alexander Hamilton, himself a Federalist, stated that the government being created was a “republican government,” and that true freedom would not be found in a dictatorship nor a true democracy, but in a moderate government.

The following table outlines some of the differences between a constitutional republic and a democracy:

Republicanism And Fundamental Rights

The foregoing discussion should not be construed as implying a necessary correlation between, on the one hand, liberalism and democracy, and, on the other, communitarianism and authoritarianism. Some versions of communitarianism approach a pure, popular democracy more closely than do some versions of liberalism, which would expressly renounce pure democracy. If a society is to be governed by a principle of collective welfare, and if notions of collective welfare are to be ascertained by consensus, then majority rule provides sufficient justification for deciding which acts should be penalized. No additional justification, with reference to the specific harm that would be caused by penalized acts, would be required. If the majority wishes to penalize gambling, alcohol consumption, flag burning, contraception, or homosexuality, then it may do so with no greater notion of harm than the sentiment that individuals and society would be better off without such things.

Ordinary right Putative harm caused by exercise of right Exercise of right may be penalized without special justification Exercise of right may not be penalized without special justification

Wilfried Nippel, inInternational Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences , 2015

Republicanism In The United Kingdom

e

Republicanism in the United Kingdom is the political movement that seeks to replace the United Kingdom‘s monarchy with a republic. Supporters of the movement, called republicans, support alternative forms of governance to a monarchy, such as an elected head of state, or no head of state at all.

Monarchy has been the form of government used in the countries that now make up the United Kingdom almost exclusively since the Middle Ages. A republican government existed in England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, in the mid-17th century as a result of the Parliamentarian victory in the English Civil War. The Commonwealth of England, as the period was called, lasted from the execution of Charles I in 1649 until the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

What Are The Ideas Of Republicanism

It stresses liberty and inalienable individual rights as central values; recognizes the sovereignty of the people as the source of all authority in law; rejects monarchy, aristocracy, and hereditary political power; expects citizens to be virtuous and faithful in their performance of civic duties; and vilifies …

0 notes

Text

America Owes Us for the Ongoing Destruction of Afrikan Life! Reparations Now!

From the New Afrikan People’s Organization and the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement

The New Afrikan People’s Organization is a revolutionary organization dedicated to independence and socialism for Afrikan descendants in the U.S. empire. NAPO is also committed to Pan-Afrikanism and anti-imperialist solidarity.

The Malcolm X Grassroots Movement is the mass association and political action wing of NAPO. MXGM is committed to self-determination, reparations, human rights for New Afrikan people and opposes sexism and genocidal policies of the US empire.

As Pan-Africanists and anti-imperialists, NAPO and MXGM stands firmly in solidarity with the struggle of Afrikan and indigenous peoples for reparations internationally as well as inside the United States. The following statement outlines our understanding of both the importance of an international struggle for reparations for our people’s and other people’s centuries long struggle to end colonial domination and slavery.

What are Reparations?

Reparations are compensation for damages inflicted on groups or individuals. The responsible party attempts to bring peace and justice by compensating the afflicted party. Reparations are an established principle in international law. The international community has held violators of human rights responsible to redress the damages it was responsible for. For example, Germany was forced to pay Israel because of its genocidal practices against Jewish people in the 1930’s and 1940’s and Iraq was forced to compensate Kuwait after the Gulf War. The United States government agreed to compensate Japanese Americans for internment in concentration camps and seizing their property during the second World Imperialist War (a.k.a. World War II).

Why Should Afrikans in the United States receive reparations?

The history of Afrikans in the United States (U.S.) is an indictment against the U.S. government in terms of violations of human rights and genocide. The U.S. government is responsible for compensating Afrikans who descendants of those Afrikans are who were held captive in North America. For twenty-five years (1783 to 1808), the United States allowed Afrikans to be legally brought into its borders. They received import duties on each captive Afrikan brought to its shores during that time. In winning its war of independence from England, the U.S. decided to maintain a system of slavery with Afrikans as its primary labor force. Despite continued individual and collective resistance by Afrikans, the American system of slavery created physical, psychological and social damage on the Afrikan population.

After slavery was declared illegal (except for punishment for “crimes”), the Americans institutionalized a system of colonial apartheid called segregation or “Jim Crow” which limited the life chances and the social and economic development of the Afrikan population in North America. From the 1870’s until the early 1920’s, the American government allowed terrorist violence against Afrikans to go virtually unchecked by its “law enforcement.”

While the American government has declared its brand of apartheid illegal, this system is so institutionalized it is maintained in most aspects of social life in the United States, including the economic system, health care, housing, and education. Afrikan people are disproportionately targeted for police harassment and mass incarceration. White supremacy continues to affect the political, economic, and social life of Afrikans in the U.S.

Is the Demand for Reparations a new issue?

After the American Civil War, Afrikans began to demand land as a form of compensation for years of unpaid labor. The slogan “Forty Acres and a Mule” is rooted in this aspiration. Fear of an Afrikan uprising for land existed throughout the southern American states. In Virginia, Tennessee and Georgia, American troops put down attempts by Afrikans to seize land.

In the 1890’s there were several efforts by Afrikans to achieve reparations. The National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief Bounty and Pension Association, headed by Callie House and Isaiah Dickerson, was a southern-based reparations movement possessed over 10,000 members. Henry McNeal Turner, a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church, called for reparations to allow our people to repatriate to Afrika.

Queen Mother (Audley) Moore represents the most tireless worker for Afrikan reparations in the Afrikan descendant movement in the U.S. A former member of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association and the Communist Party of the U.S., Queen Mother began to advocate reparations in the 1950’s. She convinced Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X to include it in the program of the Nation of Islam. She also convinced other nationalists, including Imari Obadele, founder of the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika, Oserjiman Adefumi, the founder of Oyotunji Village in South Carolina and leader of the Yoruba and traditional African religious revival movement in the U.S., as well as, Muhammad Ahmad (Max Stanford) of the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), to advocate reparations. Inspired by Queen Mother Moore, Black Power organizations like the Revolutionary Action Movement, Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and the Black Panther Party advocated reparations. Most national Black Power gatherings endorsed the concept of reparations. After the Black Economic Development Conference called for reparations in 1970, activists like Jim Forman initiated a direct-action campaign targeting predominately white Christian churches demanding reparations. This forced white denominations to direct funds to Afrikan communities.

Since 1987, the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (NCOBRA) has led the effort to achieve reparations for Afrikan descendants in the United States. NCOBRA is a united front of activists who advocate reparations. The Lost Found Nation of Islam, under the leadership of Silas Muhammad, has initiated efforts to gain international support for reparations. From 1989 until his tenure in the United States Congress ended in 2017, Representative John Conyers submitted H.R. 40, a bill to study reparations in the House of Representatives. The Conyers bill has never made it out of the Judicial committee to the floor of Congress. Several city governments, including Atlanta and Detroit have passed resolutions in support of reparations. The 2000 release of the book The Debt: What America Owes Blacks by human rights advocate Randall Robinson re-introduced the demand reparations in popular discourse. Journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates 2014 article “A Case for Reparations” invigorated the dialogue in the United States.

Global developments

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the movement towards the 2001 World Conference Against Racism (WCAR) in Durban, South Africa increased international momentum of African peoples towards reparations. The struggle resulted in a resolution in which the United Nations declared the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade “A Crime Against Humanity.” This was considered a significant victory for the reparations movement. Unfortunately, two events disrupted the forward motion.

First, three days after the conclusion of the conference, the attacks on September 11, 2001 in New York and Washington D.C., overshadowed the victory at the WCAR for U.S. based reparations activists. Secondly, the follow up Conference Against Racism in Barbados was divided by a conflict over including people of white European origin in the conference. Despite these setbacks, Afro-descendant movements in South America, notably Brazil and Venezuela, have achieved momentum post-Durban.

Additionally, a significant blow to the international reparation movement occurred after the U.S. sponsored coup in 2004 of the Lavalas government headed by Jean Bertrand Aristide in Haiti. The Aristide government had demanded twenty-one billion dollars in reparations from France, which had coerced Haiti to compensate the French government for its liberation from French colonialism. The demand for restitution remains a popular demand in Haiti despite the kidnapping of President Aristide and his seven-year banishment from Haiti.

The 2013 CARICOM countries 10 point-plan for reparations from European countries is an important development in re-asserting the demand for economic justice and for respect for the lives and humanity of our Ancestors. It also inspired reparations advocates inside the U.S. empire.

What type of redress does NAPO and the MXGM argue should be sought?

There are various proposals for reparations. The relationship between Afrikans and the United States has been an experience of conflict. The New Afrikan People’s Organization (NAPO) and the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement (MXGM) argue that Afrikan people and the United States will never have peace until reparations have been achieved on certain fundamental levels. The U.S. is in denial in terms of its crimes against the Afrikan population within its borders. Just as individuals engaged in therapy, America must first recognize its role in the oppression. The United States must acknowledge its violations against Afrikan people. Admitting to its role and apologies are not sufficient acts of justice. Acknowledgment of its human rights violations is a prerequisite to action to resolve the conflict between the United States and Afrikans.

Most reparation proposals offer financial compensation to Afrikans in America in terms of monetary payments, tax relief, or support for education. While all of these are valid there are other elements of redress which NAPO/MXGM and other forces in the New Afrikan Independence Movement are concerned. We do not believe compensating individuals thousands of dollars is a meaningful way to heal the damages experienced by Afrikans in America. Given the current balance of power and capitalist economic arrangements, individual stipends would primarily stimulate the American economy not empower the Afrikan community. We are concerned with reparation proposals that encourage our collective development and enable our people to ensure our future. The first things that our enslaved Ancestors lost were their identity and freedom. After the end of chattel slavery, our Ancestors were never allowed to choose their national identity or their relationship to the government, which sanctioned their captivity and enslavement. We should be allowed to determine what a free existence is for us, through a plebiscite. A plebiscite is a vote taken by a people to determine their national will. Some of us would prefer to be U.S. citizens. Some would prefer to be repatriated to Africa. Those of us in the New Afrikan Independence Movement desire an Afrikan government in North America on territory that our Ancestors were enslaved on and forced to work without compensation. As part of our compensation, the United States should honor and respect our right to self-determination, our choices of how We want to be free. The United States should not deny us the right to organize a vote to determine how We wish to be free nor should the US attempt to manipulate that vote. After We determine our respective choices the United States should be obligated to fulfill our demands of freedom. This is real justice!

Another form of redress is for the United States government to release all political prisoners, and prisoners of war and allow all Afrikan political exiles to return to North America, if they choose to do so. The war the United States waged on the Afrikan freedom struggle in this country is the reason political prisoners, prisoners of war and exiles exist. No real redress can exist while there is captivity or isolation of Afrikan freedom fighters.

How does NAPO and the MXGM think reparations will be achieved?

Frederick Douglas once said, “power concedes nothing without a demand.” The United States will not give us anything unless it is forced to. We might still be in slavery if our Ancestors did not strike for their freedom during the American Civil War. Without active struggle, Afrikans would not be able to vote or enjoy other things now considered basic rights in the U.S. empire. Reparations will only be achieved through a massive movement by Afrikans militantly challenging the empire. If We don’t seriously fight for it, We will never get reparations or anything else important to our existence.

We must as a people reach a consensus on reparations. As We reach a consensus, We must challenge the imperialist state on reparations. If We are serious about reparations We will not allow business as usual to occur within the empire until We get it. Without reparations, we won’t have justice and without justice for our Ancestors, and ourselves, We shouldn’t allow the U.S. empire to live in peace. This is the only way We will achieve reparations.

FREE THE LAND! RESIST SETTLER COLONIALISM AND US IMPERIALISM!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet the Inspirational Leader of UN Women

HP Inc. Garage blog

By Angela Matusik

When Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka was a young girl in South Africa, she saw firsthand what fearless women could do. “The women in my community were leading in the times of apartheid, in very risky situations,” she recalls. “They were the ones that went out when the police were repressing people, and the men were running to hide.”

The South African politician, activist, and executive director of UN Women, Mlambo-Ngcuka has devoted her career to issues of human rights, equality, and social justice, both in the public and private sectors. She has declared 2020 “a year for women” with her “Generation Equality” initiative. The intent is to focus on the benefits of gender equality, not only for women and girls, “but for everyone whose lives will be changed by a fairer world,” she says.

If governments, humanitarian organizations, and global activists could wave a magic wand and drastically change the fates of millions of women all over the world, they would have to wish for one thing: an education for each of them. It’s the biggest game-changer for women in the developing world, beyond access to basics such as safe housing, clean water, and healthcare.

“When you create opportunity for women, you actually unleash a force for good,” Mlambo-Ngcuka says. “Working with women introduces additional power that makes the world a better place.”

Mlambo-Ngcuka reflected on the recently-opened HP LIFE Centers in the municipality of Huixquilucan in greater Mexico City, and the municipalities of Zapopan and Jocotepec in Jalisco state, the fruition of a key partnership announced last fall between HP and the United Nations. HP provided technology grants to these centers, where women can learn digital literacy and job-building skills through the HP Foundation’s free online learning platform, HP LIFE.

“Education is a fundamental human right and essential to achieve gender equality,” says Michele Malejki, global head of sustainability and social impact programs at HP. “The collaboration with UN Women’s Second Chance Education program will empower thousands of women and girls by providing direct access to 21st Century skills that support employment, entrepreneurship, and economic opportunities.”

This month, the world marks International Women’s Day on March 8 and brings into the spotlight the disparities in access to education, training, and jobs that billions of women still face.

It’s one of the reasons that HP is also partnering with UN Women under UN Women’s Second Chance Education Initiative, with support from BHP Foundation, to expand digital learning opportunities for women and girls in five African countries: Senegal, South Africa, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Morocco.

Mlambo-Ngcuka is a committed partner of HP and is helping the company make progress toward its goal of enabling better learning outcomes for 100 million people by 2025.

“When you think of a leader, certain qualities often come to mind: focused, intelligent, and impactful, to name a few,” HP’s Malejki says. “Executive Phumzile embodies all of these and brings purpose-driven, authentic leadership to UN Women. We couldn’t be more proud to partner with her and are excited by what’s to come.”

The Garage caught up with Mlambo-Ngcuka in New York.

You’ve had such an amazing life as an advocate, politician, leader — always advancing equality and opportunity. How did this come to be your passion and purpose?

At a very young age, I was exposed to the power of community work. My mother was a community worker, and she ran literacy classes at home. I was surprised to see that the women, which I had known in my community, could not read or write. Because for me, they were already role models. I wanted to help provide them with additional skills so they could become more impactful people in society.

Growing up in South Africa, what role did women play in the leadership you witnessed?

Women’s leadership was always something to marvel, especially when you see it happen in very risky situations in South Africa. They were the ones that went out when the police were killing and repressing people… The women would just go out there and stand in front of the police fence and face them, and demand for the police to leave their children. That courage was just amazing and it made you feel that, ‘When I grow up, I want to be that woman too.’

Tell us about the organization you lead now, UN Women.

Well, UN Women is the agency of the United Nations that is responsible for advancing gender equality. We work with member states to help them either deal with the laws that discriminate against women or put in place laws that will advance gender equality. We deal with the whole United Nation system in order to ensure that our sister agencies are doing their bits because they also have expertise that we don't have. We pilot programs in the field to check that the policies that we're pushing on member states actually work. We test them and we are then able to promote them because we have seen for ourselves that the policies are working.

What sort of challenges do women face when it comes to being able to pursue the career of their choice?

I have to say, first, that in the last 25 years, especially, girls’ education has advanced a lot. Member states have invested a lot in girls’ education, especially, in the countries that started at the bottom. In most countries, we saw girls enrollment and presence in school reaching parity with boys. In some it even exceeded it.

However, even with all that effort, there are 263 million girls who are out of school. That means that they are likely to marry too early, because if they are not at school, they are likely not just to be at home. There are girls who are unable to take care of their health needs and the health needs of their family who do not have the means to contribute to the economy to support themselves. As a result, they depend on partners who sometimes, and most of the time, actually, abuse them.

How do your programs help?

One of the reasons why we appreciate the partnership that we have with HP is that it brings investment. It provides second chance education for girls who otherwise would have dropped out of school. It provides learning to earn because in some cases, the girls are already young women and not children that can sit in a classroom. We also are able to introduce and expose girls to technology.

What role does technology play?

Well, technology can be an equalizer, but it’s not automatic. Technology also can be a discriminator. Those who have it will advance much further and widen the gap between the technology haves and the technology have-nots. If you just introduce technology without hand holding those who are likely to be left behind, there's always a risk that you’ll make the inequality worse.

How do the HP LIFE Centers help with that?

They provide us with an opportunity to leapfrog women into the 21st Century in a place where we can use content that is already tried and tested. We are seeing that, especially, in the program in Mexico. The women who are participating in the program are really gaining power. And because HP LIFE is also online, it can be accessed by many people all over the world. It gives us the potential to scale much more quickly and creates a community of best practices. Our responsibility is then to organize people, women, and to make them aware of this opportunity, to support and accompany them in their journey.

Why is it important to invest in this work?

There are as many as 500 million women between the ages of 15 and 24 who are illiterate. They are young enough to have a long life ahead of them, so you cannot give up on them. It's important to invest in them. I have seen women who have had a second chance education become community workers, learning to move in their community with newly gained skills that help other mothers to look after their own children. For example, they can teach people in the community about nutrition and the importance of boiling water.

Read about six more inspiring leaders who are making human rights their everyday mission.

source: https://www.csrwire.com/press_releases/43946-Meet-the-Inspirational-Leader-of-UN-Women?tracking_source=rss

0 notes

Text

New world news from Time: ‘We Now Stand at a Crossroads.’ Here’s What Barack Obama Said During His First Big Speech Since He Left Office

Former President Barack Obama gave his first significant speech since he left the Oval Office on Tuesday, commemorating the 100th anniversary of Nelson Mandela’s birth.

Speaking to a crowd of around 15,000 people at the 16th Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture in Johannesburg, Obama called the South African political leader “one of history’s true giants” and someone whose “progressive, democratic vision” helped shape international policies.

Obama touched on numerous topics ranging from the need to stand up for democracy and believe in facts to the current state of politics, though he never mentioned President Donald Trump by name.

“I am not being alarmist, I’m simply stating the facts,” Obama said. “Look around — strongman politics are ascendant, suddenly, whereby elections and some pretense of democracy are maintained, the form of it, but those in powers seek to undermine every institution or norm that gives democracy meaning.”

“Too much of politics today seems to reject the very concept of objective truth,” Obama said. “People just make stuff up. They just make stuff up.”

Obama also made a reference to Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. election, saying social media “has proved to be just as effective promoting hatred and paranoia and propaganda and conspiracy theories.”

You can read the full transcript of Obama’s speech in South Africa below:

Thank you. To Mama Graça Machel, members of the Mandela family, the Machel family, to President Ramaphosa who you can see is inspiring new hope in this great country – professor, doctor, distinguished guests, to Mama Sisulu and the Sisulu family, to the people of South Africa – it is a singular honor for me to be here with all of you as we gather to celebrate the birth and life of one of history’s true giants.

Let me begin by a correction and a few confessions. The correction is that I am a very good dancer. I just want to be clear about that. Michelle is a little better.

The confessions. Number one, I was not exactly invited to be here. I was ordered in a very nice way to be here by Graça Machel.

Confession number two: I forgot my geography and the fact that right now it’s winter in South Africa. I didn’t bring a coat, and this morning I had to send somebody out to the mall because I am wearing long johns. I was born in Hawaii.

Confession number three: When my staff told me that I was to deliver a lecture, I thought back to the stuffy old professors in bow ties and tweed, and I wondered if this was one more sign of the stage of life that I’m entering, along with gray hair and slightly failing eyesight. I thought about the fact that my daughters think anything I tell them is a lecture. I thought about the American press and how they often got frustrated at my long-winded answers at press conferences, when my responses didn’t conform to two-minute soundbites. But given the strange and uncertain times that we are in – and they are strange, and they are uncertain – with each day’s news cycles bringing more head-spinning and disturbing headlines, I thought maybe it would be useful to step back for a moment and try to get some perspective. So I hope you’ll indulge me, despite the slight chill, as I spend much of this lecture reflecting on where we’ve been, and how we arrived at this present moment, in the hope that it will offer us a roadmap for where we need to go next.

One hundred years ago, Madiba was born in the village of M – oh, see there, I always get that – I got to get my Ms right when I’m in South Africa. Mvezo – I got it. Truthfully, it’s because it’s so cold, my lips stuck. So in his autobiography he describes a happy childhood; he’s looking after cattle, he’s playing with the other boys, eventually attends a school where his teacher gave him the English name Nelson. And as many of you know, he’s quoted saying, ‘Why she bestowed this particular name upon me, I have no idea.’

There was no reason to believe that a young black boy at this time, in this place, could in any way alter history. After all, South Africa was then less than a decade removed from full British control. Already, laws were being codified to implement racial segregation and subjugation, the network of laws that would be known as apartheid. Most of Africa, including my father’s homeland, was under colonial rule. The dominant European powers, having ended a horrific world war just a few months after Madiba’s birth, viewed this continent and its people primarily as spoils in a contest for territory and abundant natural resources and cheap labor. And the inferiority of the black race, an indifference towards black culture and interests and aspirations, was a given.

And such a view of the world – that certain races, certain nations, certain groups were inherently superior, and that violence and coercion is the primary basis for governance, that the strong necessarily exploit the weak, that wealth is determined primarily by conquest – that view of the world was hardly confined to relations between Europe and Africa, or relations between whites and blacks. Whites were happy to exploit other whites when they could. And by the way, blacks were often willing to exploit other blacks. And around the globe, the majority of people lived at subsistence levels, without a say in the politics or economic forces that determined their lives. Often they were subject to the whims and cruelties of distant leaders. The average person saw no possibility of advancing from the circumstances of their birth. Women were almost uniformly subordinate to men. Privilege and status was rigidly bound by caste and color and ethnicity and religion. And even in my own country, even in democracies like the United States, founded on a declaration that all men are created equal, racial segregation and systemic discrimination was the law in almost half the country and the norm throughout the rest of the country.

That was the world just 100 years ago. There are people alive today who were alive in that world. It is hard, then, to overstate the remarkable transformations that have taken place since that time. A second World War, even more terrible than the first, along with a cascade of liberation movements from Africa to Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, would finally bring an end to colonial rule. More and more peoples, having witnessed the horrors of totalitarianism, the repeated mass slaughters of the 20th century, began to embrace a new vision for humanity, a new idea, one based not only on the principle of national self-determination, but also on the principles of democracy and rule of law and civil rights and the inherent dignity of every single individual.

In those nations with market-based economies, suddenly union movements developed; and health and safety and commercial regulations were instituted; and access to public education was expanded; and social welfare systems emerged, all with the aim of constraining the excesses of capitalism and enhancing its ability to provide opportunity not just to some but to all people. And the result was unmatched economic growth and a growth of the middle class. And in my own country, the moral force of the civil rights movement not only overthrew Jim Crow laws but it opened up the floodgates for women and historically marginalized groups to reimagine themselves, to find their own voices, to make their own claims to full citizenship.

It was in service of this long walk towards freedom and justice and equal opportunity that Nelson Mandela devoted his life. At the outset, his struggle was particular to this place, to his homeland – a fight to end apartheid, a fight to ensure lasting political and social and economic equality for its disenfranchised non-white citizens. But through his sacrifice and unwavering leadership and, perhaps most of all, through his moral example, Mandela and the movement he led would come to signify something larger. He came to embody the universal aspirations of dispossessed people all around the world, their hopes for a better life, the possibility of a moral transformation in the conduct of human affairs.

Madiba’s light shone so brightly, even from that narrow Robben Island cell, that in the late ‘70s he could inspire a young college student on the other side of the world to reexamine his own priorities, could make me consider the small role I might play in bending the arc of the world towards justice. And when later, as a law student, I witnessed Madiba emerge from prison, just a few months, you’ll recall, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, I felt the same wave of hope that washed through hearts all around the world.

Do you remember that feeling? It seemed as if the forces of progress were on the march, that they were inexorable. Each step he took, you felt this is the moment when the old structures of violence and repression and ancient hatreds that had so long stunted people’s lives and confined the human spirit – that all that was crumbling before our eyes. And then as Madiba guided this nation through negotiation painstakingly, reconciliation, its first fair and free elections; as we all witnessed the grace and the generosity with which he embraced former enemies, the wisdom for him to step away from power once he felt his job was complete, we understood that – we understood it was not just the subjugated, the oppressed who were being freed from the shackles of the past. The subjugator was being offered a gift, being given a chance to see in a new way, being given a chance to participate in the work of building a better world.

And during the last decades of the 20th century, the progressive, democratic vision that Nelson Mandela represented in many ways set the terms of international political debate. It doesn’t mean that vision was always victorious, but it set the terms, the parameters; it guided how we thought about the meaning of progress, and it continued to propel the world forward. Yes, there were still tragedies – bloody civil wars from the Balkans to the Congo. Despite the fact that ethnic and sectarian strife still flared up with heartbreaking regularity, despite all that as a consequence of the continuation of nuclear détente, and a peaceful and prosperous Japan, and a unified Europe anchored in NATO, and the entry of China into the world’s system of trade – all that greatly reduced the prospect of war between the world’s great powers. And from Europe to Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia, dictatorships began to give way to democracies. The march was on. A respect for human rights and the rule of law, enumerated in a declaration by the United Nations, became the guiding norm for the majority of nations, even in places where the reality fell far short of the ideal. Even when those human rights were violated, those who violated human rights were on the defensive.