#irreverent torah

Text

(JTA) — Binya Kóatz remembers the first time she saw a woman wearing tzitzit. While attending Friday night services at a Jewish Renewal synagogue in Berkeley, she noticed the long ritual fringes worn by some observant Jews — historically men — dangling below a friend’s short shorts.

“That was the first time I really realized how feminine just having tassels dangling off you can look and be,” recalled Kóatz, an artist and activist based in the Bay Area. “That is both deeply reverent and irreverent all at once, and there’s a deep holiness of what’s happening here.”

Since that moment about seven years ago, Kóatz has been inspired to wear tzitzit every day. But she has been less inspired by the offerings available in online and brick-and-mortar Judaica shops, where the fringes are typically attached to shapeless white tunics meant to be worn under men’s clothing.

So in 2022, when she was asked to test new prototypes for the Tzitzit Project, an art initiative to create tzitzit and their associated garment for a variety of bodies, genders and religious denominations, Kóatz jumped at the chance. The project’s first products went on sale last month.

“This is a beautiful example of queers making stuff for ourselves,” Kóatz said. “I think it’s amazing that queers are making halachically sound garments that are also ones that we want to wear and that align with our culture and style and vibrancy.”

Jewish law, or halacha, requires that people who wear four-cornered garments — say, a tunic worn by an ancient shepherd — must attach fringes to each corner. The commandment is biblical: “Speak to the Israelite people and instruct them to make for themselves fringes on the corners of their garments throughout the ages” (Numbers 15:37-41) When garments that lack corners came into fashion, many Jews responded by using tzitzit only when wearing a tallit, or prayer shawl, which has four corners.

But more observant Jews adopted the practice of wearing an additional four-cornered garment for the sole purpose of fulfilling the commandment to tie fringes to one’s clothes. Called a tallit katan, or small prayer shawl, the garment is designed to be worn under one’s clothes and can be purchased at Judaica stores or online for less than $15. The fringes represent the 613 commandments of the Torah, and it is customary to hold them and kiss them at certain points while reciting the Shema prayer.

“They just remind me of my obligations, my mitzvot, and my inherent holiness,” Kóatz said. “That’s the point, you see your tzitzit and you remember everything that it means — all the obligations and beauty of being a Jew in this world.”

The California-based artists behind the Tzitzit Project had a hunch that the ritual garment could appeal to a more diverse set of observant Jews than the Orthodox men to whom the mass-produced options are marketed. Julie Weitz and Jill Spector had previously collaborated on the costumes for Weitz’s 2019 “My Golem” performance art project that uses the mythical Jewish creature to explore contemporary issues. In one installment of the project focused on nature, “Prayer for Burnt Forests,” Weitz’s character ties a tallit katan around a fallen tree and wraps the tzitzit around its branches.

“I was so moved by how that garment transformed my performance,” Weitz said, adding that she wanted to find more ways to incorporate the garment into her life.

The Tzitzit Project joins other initiatives meant to explore and expand the use of tzitzit. A 2020 podcast called Fringes featured interviews with a dozen trans and gender non-conforming Jews about their experiences with Jewish ritual garments. (Kóatz was a guest.) Meanwhile, an online store, Netzitzot, has since 2014 sold tzitzit designed for women’s bodies, made from modified H&M undershirts.

The Tzitzit Project goes further and sells complete garments that take into account the feedback of testers including Kóatz — in three colors and two lengths, full and cropped, as well as other customization options related to a wearer’s style and religious practices. (The garments cost $100, but a sliding scale for people with financial constraints can bring the price as far down as $36.)

Spector and Weitz found that the trial users were especially excited by the idea that the tzitzit could be available in bright colors, and loved how soft the fabric felt on their bodies, compared to how itchy and ill-fitting they found traditional ones to be. They also liked that each garment could be worn under other clothing or as a more daring top on its own.

To Weitz, those attributes are essential to her goal of “queering” tzitzit.

“Queering something also has to do with an embrace of how you wear things and how you move your body in space and being proud of that and not carrying any shame around that,” she said. “And I think that that stylization is really distinct. All those gender-conventional tzitzit for men — they’re not about style, they’re not about reimagining how you can move your body.”

For Chelsea Mandell, a rabbinical student at the Academy of Jewish Religion in Los Angeles who is nonbinary, the Tzitzit Project is creating Jewish ritual objects of great power.

“It deepens the meaning and it just feels more radically spiritual to me, when it’s handmade by somebody I’ve met, aimed for somebody like me,” said Mandell, who was a product tester.

Whether the garments meet the requirements of Jewish law is a separate issue. Traditional interpretations of the law hold that the string must have been made specifically for tzitzit, for example — but it’s not clear on the project’s website whether the string it uses was sourced that way. (The project’s Instagram page indicates that the wool is spun by a Jewish fiber artist who is also the brother of the alt-rocker Beck.)

“It is not obvious from their website which options are halachically valid and which options are not,” said Avigayil Halpern, a rabbinical student who began wearing tzitzit and tefillin at her Modern Orthodox high school in 2013 when she was 16 and now is seen as a leader in the movement to widen their use.

“And I think it’s important that queer people in particular have as much access to knowledge about Torah and mitzvot as they’re embracing mitzvot.”

Weitz explained that there are multiple options for the strings — Tencel, cotton or hand-spun wool — depending on what customers prefer, for their comfort and for their observance preferences.

“It comes down to interpretation,” she said. “For some, tzitzit tied with string not made for the purpose of tying, but with the prayer said, is kosher enough. For others, the wool spun for the purpose of tying is important.”

Despite her concerns about its handling of Jewish law, Halpern said she saw the appeal of the Tzitzit Project, with which she has not been involved.

“For me and for a lot of other queer people, wearing something that is typically associated with Jewish masculinity — it has a gender element,” explained Halpern, a fourth-year student at Hadar, the egalitarian yeshiva in New York.

“If you take it out of the Jewish framework, there is something very femme and glamorous and kind of fun in the ways that dressing up and wearing things that are twirly is just really joyful for a lot of people,” she said.

For some, wearing tzitzit is just about halachic egalitarian practice, and not about queering Jewish ritual items. Rachel Schwartz, a straight cisgender woman, first became drawn to tzitzit while studying at the Conservative Yeshiva in Jerusalem in 2018. There, young men who were engaging more intensively with Jewish law and tradition than they had in the past began to adopt the garments, and Schwartz found herself wondering why she had embraced egalitarian religious practices in all ways but this one.

“One night, I took one of my tank tops and I cut it up halfway to make the square that it needed. I found some cool bandanas at a store and I sewed on corners,” Schwartz recalled. “And I bought the tzitzit at one of those shops on Ben Yehuda and I just did it and it was awesome.”

Schwartz’s experience encapsulates both the promise and the potential peril of donning tzitzit for people from groups that historically have not worn the fringes. Other women at the Conservative Yeshiva were so interested in her tzitzit that she ran a workshop where she taught them how to make the undergarment. But she drew so many critical comments from men on the streets of Jerusalem that she ultimately gave up wearing tzitzit publicly.

“I couldn’t just keep on walking around like that anymore. I was tired of the comments,” Schwartz said. “I couldn’t handle it anymore.”

Rachel Davidson, a Reconstructionist rabbi working as a chaplain in health care in Ohio, started consistently wearing a tallit katan in her mid-20s. Like Kóatz, she ordered her first one from Netzitzot.

“I would love to see a world where tallitot katanot that are shaped for non cis-male bodies are freely available and are affordable,” Davidson said. “I just think it’s such a beautiful mitzvah. I would love it if more people engaged with it.”

Kóatz believes that’s not only possible but natural. As a trans woman, she said she is drawn to tzitzit in part because of the way they bring Jewish tradition into contact with contemporary ideas about gender.

“Queers are always called ‘fringe,’” she said. “And here you have a garment which is literally like ‘kiss the fringes.’ The fringes are holy.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 1

It has been taught (Niddah, end ch. 3): An oath is administered to him [before birth, warning him]: "Be righteous and be not wicked; and even if the whole world tells you that you are righteous, regard yourself as if you were wicked."

This requires to be understood, for it contradicts the Mishnaic dictum (Avot, ch. 2), "And be not wicked in your own estimation." Furthermore, if a man considers himself to be wicked he will be grieved at heart and depressed, and will not be able to serve G‑d joyfully and with a contented heart; while if he is not perturbed by this [self-appraisal], it may lead him to irreverence, G‑d forbid.

However, the matter [will be understood after a preliminary discussion].

We find in the Gemara five distinct types—a righteous man who prospers, a righteous man who suffers, a wicked man who prospers, a wicked man who suffers, and an intermediate one (Benoni). It is there explained that the "righteous man who prospers" is the perfect tzaddik; the "righteous man who suffers" is the imperfect tzaddik. In Raaya Mehemna (Parshat Mishpatim) it is explained that the "righteous man who suffers" is one whose evil nature is subservient to his good nature, and so on. In the Gemara (end ch. 9, Berachot) it is stated that the righteous are motivated by their good nature,... and the wicked by their evil nature, while the intermediate men are motivated by both, and so on. Rabbah declared, "I, for example, am a Benoni" Said Abbaye to him, "Master, you do not make it possible for anyone to live," and so on.

To understand all the aforesaid clearly an explanation is needed, as also to under-stand what Job said [Bava Batra, ch. i], "Lord of the universe, Thou hast created righteous men and Thou hast created wicked men,..." for it is not preordained whether a man will be righteous or wicked.

It is also necessary to understand the essential nature of the rank of the Intermediate. Surely that cannot mean one whose deeds are half virtuous and half sinful, for if this were so, how could Rabbah err in classifying himself as a Benoni? For it is known that he never ceased studying [the Torah], so much so that the Angel of Death could not over¬power him; how, then, could he err to have half of his deeds sinful, G‑d forbid?

Furthermore, [at what stage can a person be considered a Benoni if] when a man commits sins he is deemed completely wicked (but when he repents afterward he is deemed completely righteous)? Even he who violates a minor prohibition of the Rabbis is called wicked, as it is stated in Yevamot, ch. 2, and in Niddah, ch. I. Moreover, even he who has the opportunity to forewarn another against sinning and does not do so is called wicked (ch. 6, Shevuot). All the more so he who neglects any positive law which he is able to fulfil, for instance, whoever is able to study Torah and does not, regarding whom our Sages have quoted, "Because he hath despised the word of the Lord... [that soul] shall be utterly cut off...," It is thus plain that such a person is called wicked, more than he who violates a prohibition of the Rabbis. If this is so, we must conclude that the Intermediate man (Benoni) is not guilty even of the sin of neglecting to study the Torah. Hence he could have mistaken himself for a Benoni.

Note: As for what is written in the Zohar III, p. 231: He whose sins are few is classed as a "righteous man who suffers" this is the query of Rav Hamnuna to Elijah. But according to Elijah's answer, ibid., the explanation of a "righteous man who suffers" is as stated in Ra'aya Mehemna on Parshat Mishpatim, which is given above. And the Torah has seventy facets [modes of interpretation].

And as for the general saying that one whose deeds and misdeeds are equally balanced is called Benoni, while he whose virtues outweigh his sins is called a Tzaddik, this is only the figurative use of the term in regard to reward and punishment, because he is judged according to the majority [of his acts] and he is deemed "righteous" in his verdict, since he is acquitted in law. But concerning the true definition and quality of the distinct levels and ranks, "Righteous" and "Intermediate" men, our Sages have remarked that the Righteous are motivated [solely] by their good nature, as it is written, "And my heart is a void within me," that is, void of an evil nature, because he [David] had slain it through fasting. But whoever has not attained this degree, even though his virtues exceed his sins, cannot at all be reckoned to have ascended to the rank of the Righteous (tzaddik). This is why our Sages have declared in the Midrash, "The Almighty saw that the righteous were few, so He planted them in every generation,..." [for,] as it is written, "The tzaddik is the foundation of the world."

The explanation [of the questions raised above] is to be found in the light of what Rabbi Chayim Vital wrote in Sha'ar ha-Kedushah (and in Etz Chayim, Portal 50, ch. 2) that in every Jew, whether righteous or wicked, are two souls, as it is written, "The neshamot (souls) which I have made," [alluding to] two souls. There is one soul which originates in the kelipah and sitra achra, and which is clothed in the blood of a human being, giving life to the body, as is written, "For the life of the flesh is in the blood." From it stem all the evil characteristics deriving from the four evil elements which are contained in it. These are: anger and pride, which emanate from the element of Fire, the nature of which is to rise upwards; the appetite for pleasures— from the element of Water, for water makes to grow all kinds of enjoyment; frivolity and scoffing, boasting and idle talk from the element of Air; and sloth and melancholy— from the element of Earth. From this soul stem also the good characteristics which are to be found in the innate nature of all Israel, such as mercy and benevolence. For in the case of Israel, this soul of the kelipah is derived from kelipat nogah, which also contains good, as it originates in the esoteric "Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil." The souls of the nations of the world, however, emanate from the other, unclean kelipot which contain no good whatever, as is written in Etz Chayim, Portal 49, ch. 3, that all the good that the nations do, is done from selfish motives. So the Gemara comments on the verse, "The kindness of the nations is sin,"— that all the charity and kindness done by the nations of the world is only for their own self-glorification, and so on.

0 notes

Text

Welcome to Lin Reads the Bible, where I follow along with weekly Torah portions and then ramble my thoughts about them. This may be snarky, sometimes irreverent, and assumes that the Tanakh was not written all at once nor by God. I am not Jewish and at no point should any of this be construed as Jewish opinion.

There are a lot of misconceptions about what's in the Book and I intend to find some truth for myself. (#things that are biblically god) will tag anything that is a biblical description of the divine, vs the tag I originally used on this blog (#things that are god) which is just anything I think might be divine. I may still use that one from time to time. (#biblically accurate angels) will be any biblical descriptionof an angel, in an attempt to push back against, well, shit like my profile picture, which is not attested in the Tanakh or even Christian Bible. Ezekiel's eye-covered wheels are explicitly not angels. If something isn't tagged (#lin reads the bible) then I'm not talking about the Bible.

1 note

·

View note

Text

On the Third Day He Rose Again From the Dead.

=1105, אאאֶפֶסה, "I'm Sorry" AKA Repentance. You have to tell the Living God you are sorry. And then the violence stops for Good

The Third Day =719, זאט, Zat=za'at= reverence for mankind.

He Rose Again From the Dead= 531, "the gay" =

"This seems to urge the reader to understand that Hebrew theology concentrates on universal Truth rather than on tribal domination, while at the same time purposes to maintain social diversity instead of turning the whole earth into one big gray mass of identical citizens."

So the fact Christ rose from the dead was not to show He could overcome death, that was a given, but to show He could overcome what might have ended up as irreverence for mankind and the establishment of a blood thirsty tribe that did not follow the Decrees and could easily walk away from manslaughter with all the wrong ideas.

Human beings create a vacuum of need around them which we need the full cooperation of everyone else to fill. If we sacrifice for the sake of this, things work, we can govern ourselves and do so happily. If we believe otherwise, we sacrifice the very mechanism God created for our welfare- something the Torah calls Padan Aram "the New Standard."

The verb פדה (pada) describes a letting go of an old standard (say, phonetic spelling) and assuming a new one (standardized spelling). The new standard may appear more restrictive at a personal level but it allows a much greater precision and thus basin of exchange and thus liberty at the collective level.

This verb speaks of an individual price paid for collective freedom and is as such often translated as to ransom or redeem. In the stories of the Bible, the old standard often appears as captor or abductor or slave-driving task master.

Nouns פדוים (peduyim), פדות (pedut), פדיום (pidyom), פדיון (pidyon) and פדין (pidyon) all mean ransom or price of redemption.

I believe God is still trying to walk us through the Crucifixion and the Resurrection and has provided the answers to us here today. I think the New Testament is this thing called Padan Aram, a New Standard instead.

0 notes

Text

4. Parsha Vayera, “The Yoke.” From Genesis 18:1–22:24.

From Parsha Lekh Lekha, “The Becoming”. God says the government of men must allude to and complete the wholeness of each man. It exists solely for the purposes of enabling the pursuit of the unknown within each of us, to guarantee this can be done ethically, fairly, and safely, and benefit the culture.

in Parsha Four, we look at the ways Abraham stewards this process during early stage human evolution, prior to the onset of emotions a time during which the ego yet requires yoking:

The Three Visitors

18 The Lord appeared to Abraham near the great trees of Mamre [from being well fed] while he was sitting at the entrance to his tent in the heat of the day. 2 Abraham looked up and saw three men standing nearby. When he saw them, he hurried from the entrance of his tent to meet them and bowed low to the ground.

3 He said, “If I have found favor in your eyes, my lord,[a] do not pass your servant by. 4 Let a little water be brought, and then you may all wash your feet and rest under this tree. 5 Let me get you something to eat, so you can be refreshed and then go on your way—now that you have come to your servant.”

“Very well,” they answered, “do as you say.”

6 So Abraham hurried into the tent to Sarah. “Quick,” he said, “get three seahs[b] of the finest flour and knead it and bake some bread.”

7 Then he ran to the herd and selected a choice, tender calf and gave it to a servant, who hurried to prepare it. 8 He then brought some curds and milk and the calf that had been prepared, and set these before them. While they ate, he stood near them under a tree.

9 “Where is your wife Sarah?” they asked him.

“There, in the tent,” he said. [Tents are the heart, where the imprint of the Testimony Stones takes place during the Seven Sacrifices, it is the crucible where one faces all the gossip, slander, the wiles of our flawed perception of history, our animal nature and traditions and become Israeli, it is the desert we cross in order to Overcome. It is where Sarah the Queen of Israel resides.]

10 Then one of them said, “I will surely return to you about this time next year, and Sarah your wife will have a son.”

= The product of God, the Father of Compassion and the tilling of mankind= Abraham’s son. He rests at the entrance of the Torah, and descends at Mid Day- after the third sacrifice, the Dove, to instruct. This completes hospitality to the Question, the Answer, and the Descent and takes place once a young man walks on his nice clean feet over to the "tree".

Afterwards, he rests, he undergoes Shabbat, is reborn and yoked to the future."

The Three Archangels, Michael, the Question, "Who is like God?" Gabriel, "The Answerer, the Mighty is He" and Raphael, "Descended from God" are the Torah Tantras inherent to the feeding of the young men.

They are preparation for an in depth instruction in history, the Torah, and all the tenets of civilized men symbolized by the consumption of Curds, bread, milk, and the calf; and be sure to notice we are not observing Kosher here:

Bread of the finest flour= equal the very best things men can offer each other from field to table.

Milk= parents

Curds= the fermenting of oneself out of childhood, AKA the calf. Calf have to grow up.

God watches from under the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil- at last he thinks he can trust people to go jigger the tree when they are mature, ready, and responsible and head off into their semi-adult lives, unlike the completely irreverent one of Adam and Eve.

Only after the yesterday, today, and tomorrow the Three Archangels that govern existence are satisfied a man demonstrate his sentience will God allow him to eat what is prepared for him.

Abraham is impressed with this idea and invests in a new generation. Even still, Sarah is skeptical things will end up being materially different. Something, she thinks, is missing:

Sarah’s Laugh

Now Sarah [the Monarchy] was listening at the entrance to the tent, which was behind him. 11 Abraham and Sarah were already very old, and Sarah was past the age of childbearing. 12 So Sarah laughed to herself as she thought, “After I am worn out and my lord is old, will I now have this pleasure?”

13 Then the Lord said to Abraham, “Why did Sarah laugh and say, ‘Will I really have a child, now that I am old?’ 14 Is anything too hard for the Lord? I will return to you at the appointed time next year, and Sarah will have a son.”

15 Sarah was afraid, so she lied and said, “I did not laugh.”

But he said, “Yes, you did laugh.”

Isaac, the child, “He will laugh” is the one born as a reward for Abraham’s rearing of the Three Men, one was a bull, the other a ram, the third a dove, and their release into the world as a calf, a new city-state.

Now the Lord and a Monarchy are going to laugh together. Why did Sarah deny she was laughed? Sarah was afraid. Afraid of what?

Sodom and Gomorrah, that’s what. How was Sarah to know the next generation was not going to fall prey to the call of the wilderness like the people of S&G or Noah?

When one laughs and recants it means the laughter is sarcastic. Sarah laughs and says "I've been around the block a few times, so no thanks." But God reassures her (and us) in the appearance of the Three Men that will not happen with the birth of Isaac.

The Three Angels represent what is not impersonal about nature, and how we must be yoked to the Personality that created the Heavens and the Earth in Bereshit. Everything in the Torah is organic, originates from the rays of the Solar Deity and is always carrying out his wishes.

The Three Angels are the First Three Days, which are the substratum of the natural world, upon which all things walk, swim, or fly. Neglect of the life giving properties God and man share as embodied life forms is the cause of famine and violence.

We drop down to Two Angels- Two Days as the fate of Sodom and Gomorrah becomes clear- the sea of violence was overrunning the shore we establish by the Third.

The loss of Daytime in the Torah almost always indicates an increase in corruption and loss of contingencies for mankind. Are the Flood and Sodom and Gomorrah story versions of the Wrath of God for naughty children or strategies God wants us to follow for restoring them?

They are real. The Torah says to protect the gazelle like the lion. Tyrants and violent persons who use superstition instead of the Traditions to govern and create floods, famines, and diseases must be put to death.

Abraham Pleads for Sodom

16 When the men got up to leave, they looked down toward Sodom “submission to tyranny”, and Abraham walked along with them to see them on their way. 17 Then the Lord said, “Shall I hide from Abraham what I am about to do? 18 Abraham will surely become a great and powerful nation, and all nations on earth will be blessed through him.[c]19 For I have chosen him, so that he will direct his children and his household after him to keep the way of the Lord by doing what is right and just, so that the Lord will bring about for Abraham what he has promised him.”

20 Then the Lord said, “The outcry against Sodom and Gomorrah is so great and their sin so grievous 21 that I will go down and see if what they have done is as bad as the outcry that has reached me. If not, I will know.”

22 The men turned away and went toward Sodom, but Abraham remained standing before the Lord.[d]23 Then Abraham approached him and said: “Will you sweep away the righteous with the wicked? 24 What if there are fifty righteous people in the city? Will you really sweep it away and not spare[e] the place for the sake of the fifty righteous people in it? 25 Far be it from you to do such a thing—to kill the righteous with the wicked, treating the righteous and the wicked alike. Far be it from you! Will not the Judge of all the earth do right?”

26 The Lord said, “If I find fifty righteous people in the city of Sodom, I will spare the whole place for their sake.”

27 Then Abraham spoke up again: “Now that I have been so bold as to speak to the Lord, though I am nothing but dust and ashes, 28 what if the number of the righteous is five less than fifty? Will you destroy the whole city for lack of five people?”

“If I find forty-five there,” he said, “I will not destroy it.”

29 Once again he spoke to him, “What if only forty are found there?”

He said, “For the sake of forty, I will not do it.”

30 Then he said, “May the Lord not be angry, but let me speak. What if only thirty can be found there?”

He answered, “I will not do it if I find thirty there.”

31 Abraham said, “Now that I have been so bold as to speak to the Lord, what if only twenty can be found there?”

He said, “For the sake of twenty, I will not destroy it.”

32 Then he said, “May the Lord not be angry, but let me speak just once more. What if only ten can be found there?”

He answered, “For the sake of ten, I will not destroy it.”

33 When the Lord had finished speaking with Abraham, he left, and Abraham returned home.

God's argument with Abraham takes place around the world every day- can you save oppressed people one at a time or not? The answer is no. While even one despotic regime exists and propagandizes its behavior, the entire human race is at risk from the projection of force and its ideas.

Compassion, or worse, complacency for tyrants is forbidden by the Torah.

God tells Abraham this, he said it to Noah, to Moses and to Joshua. The messages, messengers and audiences of violent men must all be put to the sword as soon as the outcries of their victims are heard.

Sodom and Gomorrah Destroyed

19 The two angels arrived at Sodom in the evening, and Lot was sitting in the gateway of the city. When he saw them, he got up to meet them and bowed down with his face to the ground. 2 “My lords,” he said, “please turn aside to your servant’s house. You can wash your feet and spend the night and then go on your way early in the morning.”

“No,” they answered, “we will spend the night in the square.”

3 But he insisted so strongly that they did go with him and entered his house. He prepared a meal for them, baking bread without yeast, and they ate. 4 Before they had gone to bed, all the men from every part of the city of Sodom—both young and old—surrounded the house. 5 They called to Lot, “Where are the men who came to you tonight? Bring them out to us so that we can have sex with them.”

-> Remember, intercourse is the mixing of intentions with the desire to behave and bear fruits. Violent men are not permitted to “have sex” with other men and spread their disease.

The fact Lot served the angels bread without yeast is a hint as to the real meaning behind Lot's comments about the wicked sex. Leavening using yeast, a fungus, diseases the bread just as violence diseases one person to the next.

6 Lot went outside to meet them and shut the door behind him 7 and said, “No, my friends. Don’t do this wicked thing. 8 Look, I have two daughters who have never slept with a man. Let me bring them out to you, and you can do what you like with them. But don’t do anything to these men, for they have come under the protection of my roof.”

--> Lot, who is “covered”, the son of Haran, the “mountaineer” meaning a man who attained Ararat, or exceeded his violent tendencies, says “you are too violent, try Midrash “seek answers to religious questions” and Aggadah, “from the narrative.”

Lot felt religion could steady the crowd, keep it from spreading its lies, corruption, and impropriety to the outside, but they were determined:

9 “Get out of our way,” they replied. “This fellow came here as a foreigner, and now he wants to play the judge! We’ll treat you worse than them.” They kept bringing pressure on Lot and moved forward to break down the door.

10 But the men inside reached out and pulled Lot back into the house and shut the door. 11 Then they struck the men who were at the door of the house, young and old, with blindness so that they could not find the door.

12 The two men said to Lot, “Do you have anyone else here—sons-in-law, sons or daughters, or anyone else in the city who belongs to you? Get them out of here, 13 because we are going to destroy this place. The outcry to the Lord against its people is so great that he has sent us to destroy it.”

14 So Lot went out and spoke to his sons-in-law, who were pledged to marry[f] his daughters. He said, “Hurry and get out of this place, because the Lord is about to destroy the city!” But his sons-in-law thought he was joking.

15 With the coming of dawn, the angels urged Lot, saying, “Hurry! Take your wife and your two daughters who are here, or you will be swept away when the city is punished.”

16 When he hesitated, the men grasped his hand and the hands of his wife and of his two daughters and led them safely out of the city, for the Lord was merciful to them. 17 As soon as they had brought them out, one of them said, “Flee for your lives! Don’t look back, and don’t stop anywhere in the plain! Flee to the mountains or you will be swept away!”

18 But Lot said to them, “No, my lords,[g] please! 19 Your[h] servant has found favor in your[i] eyes, and you[j] have shown great kindness to me in sparing my life. But I can’t flee to the mountains; this disaster will overtake me, and I’ll die. 20 Look, here is a town near enough to run to, and it is small. Let me flee to it—it is very small, isn’t it? Then my life will be spared.”

21 He said to him, “Very well, I will grant this request too; I will not overthrow the town you speak of. 22 But flee there quickly, because I cannot do anything until you reach it.” (That is why the town was called Zoar.[k]) [humility]

23 By the time Lot reached Zoar, the sun had risen over the land. 24 Then the Lord rained down burning sulfur on Sodom and Gomorrah—from the Lord out of the heavens. 25 Thus he overthrew those cities and the entire plain, destroying all those living in the cities—and also the vegetation in the land. 26 But Lot’s wife looked back, and she became a pillar of salt.

-> the absence of a door due to blindness is obvious, Lot gave them a chance to read and reflect, just as Abraham asked if God would allow.

The rising of the sun, and a journey to the mountain is Zoar, “humility before God, either to repent or to be glad.”

Sulfur or brimstone is “never again.” To sulfur the land is to make it impossible to support life ever again. Moses said God sulfured Sodom and Gomorrah because he meant it- no more elections, no more organizations, creepy people and their weird kids, it’s over, never again.

As for the salty sacrifice of his wife, Edith “passed over”, it’s Lot’s commitment on his end never to associate with people that endorse, support, elect political leaders or religionize violence.

“Because there is a sacrificial covenant, the Torah also uses this covenant as a model for other covenants, as both the priestly covenant (Numbers 18:19) and the Davidic covenant (2 Chronicles 13:5) are called “covenant of salt” because they are upheld just as the sacrificial covenant of salt.”

The notion of an enduring covenant—one that continues through the generations in particular—is important in both Numbers (where the verse specifically discusses Aaron’s descendants) and in Chronicles (where this is part of a demand by David’s great-grandson, Abijah, that a challenger submit to his authority). But it’s not immediately clear why this “covenant” of salt on sacrifices is so quintessentially enduring. “

see https://www.jtsa.edu/torah/a-covenant-of-salt/

27 Early the next morning Abraham got up and returned to the place where he had stood before the Lord. 28 He looked down toward Sodom and Gomorrah, toward all the land of the plain, and he saw dense smoke rising from the land, like smoke from a furnace.

29 So when God destroyed the cities of the plain, he remembered Abraham, and he brought Lot out of the catastrophe that overthrew the cities where Lot had lived.

-> Notice the inversion of the relationship. God in a moment of deep reflection remembers Abraham and his intense need to pray for the welfare of the doomed people of Sodom and Gomorrah. God did what had to be done, but He didn’t forget about the wound it left in Abraham’s heart.

Lot and His Daughters

30 Lot and his two daughters left Zoar "smallness, little" and settled in the mountains, for he was afraid to stay in Zoar. He and his two daughters lived in a cave. 31 One day the older daughter said to the younger, “Our father is old, and there is no man around here to give us children—as is the custom all over the earth. 32 Let’s get our father to drink wine and then sleep with him and preserve our family line through our father.” [wine is a symbol of the pinnacle of civilization].

-> Caves are the hollow space between the ears in the mind. Lot and the girls shack up in a cave and drink wine, the elixir of prosperity in order to achieve some interest results in that regard:

33 That night they got their father to drink wine, and the older daughter went in and slept with him. He was not aware of it when she lay down or when she got up.

34 The next day the older daughter said to the younger, “Last night I slept with my father. Let’s get him to drink wine again tonight, and you go in and sleep with him so we can preserve our family line through our father.” 35 So they got their father to drink wine that night also, and the younger daughter went in and slept with him. Again he was not aware of it when she lay down or when she got up.

-> Night time is when the future is born; just as God emerged out of the darkness of endless night to create the first day and rear life for all eternity, so did Lot's daughters use the cover of darkness to bring important new villagers into existence.

36 So both of Lot’s daughters became pregnant by their father. 37 The older daughter had a son, and she named him Moab[l]; [water of the father] he is the father of the Moabites of today. 38 The younger daughter also had a son, and she named him Ben-Ammi[m]; “son of my people” he is the father of the Ammonites[n] “kinsman” of today.

-> Normally the youngest son is sent out to reproduce with foreigners. The incest between Lot and his two unnamed daughters is the only time it is used formally as a vehicle for turning an intention into the fruits of action, the mechanism behind all sexual intercourse in the Torah.

The only way to properly understand what was so important about Lot's experiences that incest- which is forbidden -was employed is to analyze the results: The Moabites, from Devarim:

9 Then the Lord said to me, “Do not harass the Moabites or provoke them to war, for I will not give you any part of their land. I have given Ar "a city that is bare, out in the open"" to the descendants of Lot "covered by God" as a possession.”

-> The most innocent city, one that is barren of violence and injustice is the inheritance of persons who are learned.

10 (The Emites "fearsome" used to live there—a people strong and numerous, and as tall as the Anakites "tall formidable". 11 Like the Anakites, they too were considered Rephaites "terribles" , but the Moabites called them Emites. 12 Horites "the cavemen" used to live in Seir, "hairy, horrors" but the descendants of Esau drove them out. They destroyed the Horites from before them and settled in their place, just as Israel did in the land the Lord gave them as their possession.)

-> A fearsome people, strong, and powerful, the descendants of Esau lived in Moab but were replaced by people that resulted from Lot's union with his daughters, after God informed the Moabites "traditionalists" they were "naked" meaning he gave them knowledge from the Tree, intending for them to grow into their stakeholder's roles as He did with Adam and Eve.

Traditionalists are always challenged for power over the future; it is logical they were also once the challengers. Without challengers we have no future potential, which explains the urgency behind the why God allowed the transgression of incest between Lot's daughters and their father to succeed.

The same is true of the Ammonites, the descendants of Ben Ammi, the other son Lot's daughters created:

The Ammonites, also from Devarim:

17 the Lord said to me, 18 “Today you are to pass by the region of Moab at Ar "The Mountains Beyond the City." . 19 When you come to the Ammonites "kinsmen", also "villagers" do not harass them or provoke them to war, for I will not give you possession of any land belonging to the Ammonites. I have given it as a possession to the descendants of Lot.”

20 (That too was considered a land of the Rephaites "horribles", who used to live there; but the Ammonites called them Zamzummites "schemers". 21 They were a people strong and numerous, and as tall as the Anakites.

The Lord destroyed them from before the Ammonites, who drove them out and settled in their place. 22 The Lord had done the same for the descendants of Esau, who lived in Seir "shaggies", when he destroyed the Horites "cavemen" from before them. They drove them out and have lived in their place to this day.

->Ammonites are "the in-crowd, to whom secrets are known." Possessions belonging to the "secret keepers" AKA, teachers, which were given to Lot, "covered, to wrap closely in secrecy" which makes sense.

Schemers with big egos are always driven away by grown ups like Esau and well-educated men like Lot.

Abraham and Abimelek

20 Now Abraham moved on from there into the region of the Negev (scorched, dry of violence) and lived between Kadesh [the sacred] and Shur [and the bull, that which is raised]. For a while he stayed in Gerar [to sojourn], 2 and there Abraham said of his wife Sarah, “She is my sister.” Then Abimelek king [my father is king] of Gerar sent for Sarah and took her.

=The compassionate one, who is raised without violence, between the sacred and the rest of the nation is dragged away and wed to it [by the age of citizenship].

3 But God came to Abimelek in a dream one night and said to him, “You are as good as dead because of the woman you have taken; she is a married woman.”

4 Now Abimelek had not gone near her, so he said, “Lord, will you destroy an innocent nation? 5 Did he not say to me, ‘She is my sister,’ and didn’t she also say, ‘He is my brother’? I have done this with a clear conscience and clean hands.”

="Nations cannot be naive about the potential for scum to do unconscionable things with a clear conscience."

Sacrifice the guilty first thing in the morning or everyone who has been violated or it be as if they were treated as if they had died."

6 Then God said to him in the dream, “Yes, I know you did this with a clear conscience, and so I have kept you from sinning against me. That is why I did not let you touch her. 7 Now return the man’s wife, for he is a prophet, and he will pray for you and you will live. But if you do not return her, you may be sure that you and all who belong to you will die.”

8 Early the next morning Abimelek summoned all his officials, and when he told them all that had happened, they were very much afraid. 9 Then Abimelek called Abraham in and said, “What have you done to us? How have I wronged you that you have brought such great guilt upon me and my kingdom? You have done things to me that should never be done.” 10 And Abimelek asked Abraham, “What was your reason for doing this?”

11 Abraham replied, “I said to myself, ‘There is surely no fear of God in this place, and they will kill me because of my wife.’ 12 Besides, she really is my sister, the daughter of my father though not of my mother; and she became my wife. 13 And when God had me wander from my father’s household, I said to her, ‘This is how you can show your love to me: Everywhere we go, say of me, “He is my brother.”’”

14 Then Abimelek brought sheep and cattle and male and female slaves and gave them to Abraham, and he returned Sarah his wife to him. 15 And Abimelek said, “My land is before you; live wherever you like.”

16 To Sarah he said, “I am giving your brother a thousand shekels[o] of silver. This is to cover the offense against you before all who are with you; you are completely vindicated.”

It is not the death of compassion nor the end of the dream if a society that operates according to conscience. Conscience is the yoke it is the vindicator, we dream of a world that abides by it when we are awake.

Sarah, the wife of Abraham, the "Queen and Country" can still be wed to Abraham "the Father of Compassion" and deal appropriately with persons without the ability to live amongst ordinary persons without violence or ignominy.

-> 1,000 Shekels of Silver=

A shekel of silver= two half shekels of common decency shared between oneself and the rest of humanity.

The numerical value comes from mapping out the values of "Moses" [in Hebrew, "Moshe" = 345] is the same as that of the divine name E-l Sha-dai.

"Moshe" is spelled: mem-shin-hei = 40 + 300 + 5 = 345.

"E-l Sha-dai" is spelled: alef-lamed, shin-dalet-yud

When these names are spelled out and the kolel is added, their numerical value is 1000.

Alef : alef-lamed-pei 1 + 30 + 80= 111

Lamed : lamed-mem-dalet 30 + 40 + 4 =74

Shin: shin-yud-nun 300 + 10 + 50=360

Dalet: dalet-lamed-tav 4 + 30 + 400=434

Yud: yud-vav-dalet 10 + 6 + 4= 20

TOTAL = 1000

This 1000 [in Hebrew, "elef"] is the 1000 of bina, for these divine names are located there; this is the mystical meaning of the statement: "Alef-beit, alef-bina."

A shekel of silver= two half shekels of common decency shared between oneself and the rest of humanity.

17 Then Abraham prayed to God, and God healed Abimelek, his wife and his female slaves so they could have children again, 18 for the Lord had kept all the women in Abimelek’s household from conceiving because of Abraham’s wife Sarah.

-> God is trying to establish a kingdom that is ruled by compassion. There is to be one axiom for this, “Abraham and Sarah” “Kingdom and Kindness” and it must not change. See my comments above.

Sarah and Abraham’s father, Terah was the “breath”. Without the breath of life we have nothing, that much is obvious, but the Torah insists it is given to us to make Kingdoms that are civil. This is what is meant by Ar, "The naked city."

Whether or not we can use violence to address violence, the answer is yes, we can. When the rules are broken and the tie that binds is broken it is no longer violence, it becomes justice.

Such cases, as seen in Europe during the fallout after WWII and in America after the Trump era, where rabid political movements mobilized State Power against the People, all compassion has to be suspended and the message, the messenger and its audiences have to be removed from the human genome.

So long as they are present, the model discussed in the Torah will not work. This we see tossed about in the tale of Abimelek and Abraham.

Abimelek, the “father king” who meets Abraham and Sarah, who are on a sojourn decides life in the kingdom would more desirable without “Great compassion”, so Abimelek abucts Sarah and gives it a try.

When he realizes without Abraham, the new nation will devolve into Sodom and Gomorrah, he changes his mind.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hashem be like “I know a spot” and then it takes you 40 years to actually get there.

865 notes

·

View notes

Photo

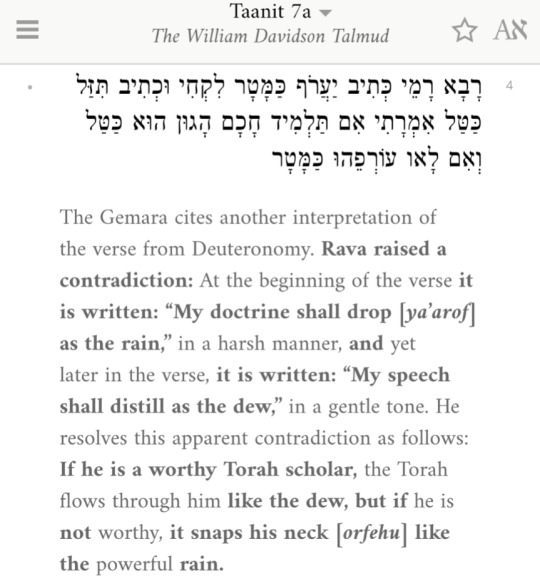

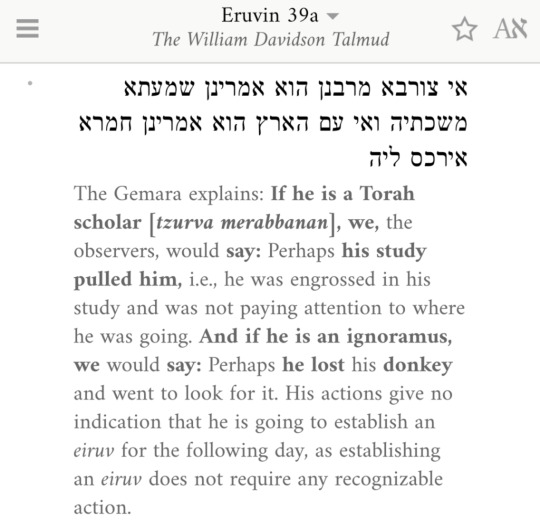

Daf Yomi Week 97: It’s Raining Mensch

Shabbat shalom and welcome, new readers and old! Please come join in our discussion of How Great Rain Is and how one defines cake versus cookies. Have a brownie, they’re outliers.

I almost chose this passage for today’s daily daf posting simply because I love books that are somehow given spiritual agency, but I saved it for the Week In Review because I wanted to talk about active books. An unworthy Torah scholar can get his neck snapped by the Torah? Fuckin’ here for it! Just as wee Dad Yomi, many years ago when very much too young to be encountering German Surrealism, fell in love with The Testament Of Dr. Mabuse because Mabuse wrote a book that would hypnotize you into doing his bidding if you read it. Later I would discover HP Lovecraft and the mythos surrounding the Necronomicon, and much later still The Magnus Archives with its murderous, disease-inducing, madness-driving Leitners. I love a dangerous book.

In life, on a day to day basis, I’m not terribly respectful of books as objects. I own a few that are semi-rare, were expensive to procure, or were gifts from particularly well-loved loved ones, and I treat those gently because they’re not easily replaced. But most of my books are pretty cheap and not hard to come by, and it’s the message and not the object that I value, so many are rather battered from being shoved into backpacks or left on the coffee table for days. I’m on copy five or six of Terry Pratchett’s “Small Gods” at this point, though part of that is the eternal lending-of-books-and-not-getting-them-back. A small price to pay to get my friends interested in reading Terry Pratchett, honestly. The point is, holding the ideas of “this book is simply an object” and “some books can kill you if you don’t respect them” together in my head at once is a very pleasurable cognitive dissonance.

In a way, of course, Talmud is an extremely active book. It’s not only a set of laws and strong recommendations but also multigenerational, centuries-spanning discourse on how one ought to live one’s life, everything from avoiding turnips to myths about rabbis with laser eyes to the minutiae of oven maintenance on the Sabbath. It’s Jews “showing the work” like in math class. And like many spiritually active books, it induces a lot of fear in a lot of people.

In that way I’m glad Daf Yomi exists, because it gathers up everyone daring enough to venture in and offers a pathway through it, even though the book itself may be less than compelling most of the time. Daf Yomi is not a course of study; it’s just the stones on the pathway through the forest, and how often you wander off the path is up to you. I’m still not positive it’s the best way to interact with the Talmud, because it’s a little bit like reading the dictionary at times -- not really how the book was meant to be used or the best way to use it -- but the longer I engage with it the more I think it is nonetheless important that it exists, simply to offer a demystification. Sort of metaphorically like a back-of-book index to the Necronomicon; tough to maintain the mystique and terror when you see everything laid out alphabetically by subject. Hard to be afraid of reading Daf Yomi when you get only a small daily dose that’s mostly about rain, or poop, or counting months.

289 weeks to go! Let’s all just hope the Talmud doesn’t go around snapping necks for irreverence, or I’m in big trouble.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

August 21: my kaddish month

I’ve sent this to a number of people, but I’m putting it here too in case some readers who might be interested will stumble across it:

A little more than a month has passed since Cindy died, and I get asked a lot how I’m doing. My standard answer starts with a couple ways of framing:

--- the earthquake is over, but there are lots of unpredictable emotional aftershocks

--- I’m past the Shock & Numbness phase, but normal life doesn’t seem normal. Lots of How Can This Be Real moments that can be disorienting and distressing

--- many times emotions collide: how much to lean into or away from grief, how to feel it’s OK to feel OK when I do, how keep her with me and move forward too, etc

I suppose at some point a fascination with grief can start to make others uncomfortable, but grieving has a logic of its own. One key part of “after” life was the 30 days of daily religious services I attended to honor her memory. I found the routine and --- surprisingly, the ritual --- spiritually nourishing. Cindy’s eyebrows always shot up at the word “spiritual.” Usually mine too. I hope those of you I send these four pages to don’t find it too tedious Perhaps it’s a way of keeping Cindy in your thoughts and hearts too…

I am a most unlikely daily mourning ritual observer. I didn’t do it for my father, and he asked us not to. But the ritual mourning prayers and the place where I’d be doing it meant a lot to Cindy, so I just committed without much deliberation. One problem in writing about a fairly traditional type of observance is that the spectrum of Jewish religious practice can be mystifying, even to many Jews. So how explain it to outsiders? I’ve tried to do it without being either too reverent or irreverent.

One basic mourning commitment is to say “kaddish”, the mourner’s prayer, for a set amount of time. Jewish practice and custom is intellectually intricate and often arcane; there are rules and exceptions to rules and different interpretations of rules, etc. There are other customs/demands for remembrance too. Many think of saying kaddish as a year long commitment. Plus yearly anniversaries, set to a moving Hebrew calendar --- just to add to the degree of difficulty. But even the year thing has permutations: actual practice for some groups is 11 months, not 12.

Why?. Different interpreters and communities make their own choices on duration. Our ritual director says “eleven.” Basically, some 13th century source says that “the wicked in Gehinom took 12 months for their souls to reach the highest levels of heaven.” But most Jews don’t even believe in a physical heaven!? Never mind. So, the reasoning goes, if the wicked took 12 months, we’ll mourn for 11: because our beloved Was Not Wicked. Welcome to Talmudic reasoning. But, traditionally, the year(ish) is for parents and children. For spouses the allotted time is 30 days. Though many people today may just do a year for anyone in the family. Thirty struck me as the perfect amount for the act to stay meaningful, helpful and not something I would treat as an increasingly resented chore.

It’s not a prayer that religious custom allows you to say by yourself. You need a minyan (quorum) of 10. It used to be men, but now men or women, at least at our conservative temple (shul, synagogue, whatever --- more insider confusing terminology). But some do say it by themselves for the comfort it brings if finding a group is too arduous. And I cheated a couple days by joining the group virtually. But I found being with a gathering of supporters did matter to me. I could have gone to a shorter evening service to do this, but preferred the morning time. And came to think a 40ish minute observance time a good block to have meaningful daily impact.

And then there’s the prayer itself. I realized right away that the weekday morning prayer service had many different kaddishs, similar prayers of thanks for and praise to a divine entity. But there’s one specific mourner’s version, said 3 times in oour short 40ish minute service. Twice, almost in succession at the end --- overkill or emphasis, depending on your point of view. Why the repeats? Haven’t pursued that yet. And, as some of you know, the prayer for the dead doesn’t mention dying or losing loved ones or honoring their memory, etc. It just profusely praises God (and lots of different words or phrases to refer to such entity since he/she/it is too holy and all powerful to mention the Real Name). Some phrases: “May god’s name be exalted and hallowed, his sovereignty soon accepted… glorified, celebrated, lauded, worshiped, exalted, honored, extolled and acclaimed… Lots of current Jewish religious practice incorporates the Middle Ages wholesale. Or earlier. Read the English on the facing page of the prayer book and much of the service sounds like the practice of a small, threatened tribe huddling in the desert thousands of years ago.

There’s a lot about Jewish practice that seems natural and essential to practitioners but might alienate the uninitiated. Or reluctant observers like me. The head coverings. The shoulder covering prayer shawls. The standing for this (many do: why not all??!), turning right for that, covering eyes for this line, fingering prayer shawl strings (tzitzit) for that. Whew. So many prayers and practices for so many different occasions. Designed, I’ve thought, to cement the devotion of believers. But it repel skeptics, too, I surmise.

One such example: in these early services most men put on tefillin. Leather straps with little black boxes attached (a prayer inside) that have very specific wrapping/unwrapping procedures for arms and head. It’s deeply moving to believers, but I’ve always thought it look repellent or ridiculous. Way too much like the garb of the ultra orthodox “crazies.” There are lots of I’ll do this/not that decisions in religious practice. I understand there’s a tenuous dynamic that exists between any minority and majority community, and clinging to tradition and being true to oneself can seem preferable to “selling out” to fit in. But sometimes it strikes us skeptics as more a clinging to “guns and religion” type intransigence.

So, if you walked in on these services cold (I was lukewarm), there’s lots that would be pretty mystifying and potentially off-putting. How could you possibly fit in? In fact, I believe I was the only new guy or gal over my month. And there had to be a decent number of temple members who have lost family members during the time I attended. Seemingly no person younger than I was doing the morning kaddish thing. And usually I was the only or 1 of 2 who didn’t put on tefillin. Men. Women usually don’t. Though one of our female rabbis did. Good for her, though I wasn’t tempted to follow.

I could fit in and feel comfortable at these services because a) I knew people there b) I was committed to being there and c) people took care of me. I no longer bristled at the imputation (real or just in my head?) that I’m a Bad Jew and I need instruction to be a Good One. This time I felt many there had cherished Cindy, understood why I was there, and quietly welcomed me. I was willing to look/be ignorant and accept guidance.

It was reassuring to see many of Cindy’s compatriots from the temple sisterhood there day after day too. The whole group (20 to 40 most days) was interesting to observe: lots more joking and side conversations during the service than I’d imagined. And there was the guy older than I who usually wore cycling shorts and shirt, the much older guy who sat to my right who usually shuffled in 15 minutes late, etc etc. Lots of accomplished people and interesting stories for another writer’s version. And --- most days --- someone called out the pages so I had some sense where we were.

I can read Hebrew if I already know the prayer or chant. So I can’t really read Hebrew anymore. Much of the service is praising God’s amazing powers, thanking him for singling out and helping Jews (don’t let anti-Semites see this!), an intricate mix of different intricate sections that over days start to fit a pattern. There are a always some bits in any prayer book that I find edifying and worth recalling; often I’m reading in one place when the service is in another. My favorite in this one:

Rabbi Schuel ben Nahmani said: We find that the Holy One created everything in the world; only falsehood and exaggeration were not God’s doing. People devised those on their own.

There’s no sermon on any days, just the chanting. And different melodies for different sections. And torah reading ritual (I could spend pages on this alone) Monday and Thursday. I still have to learn why those days. I preferred the shorter days without.

I was most fortunate to have a long time neighbor and, like Cindy, long time temple leader who I was delighted to learn (only some 30 some years later) is a regular attendee of daily morning services. Like Cindy, he has the ability I don’t to take what’s worthwhile in religious practice and ignore the rest. He credits Cindy with his reading the new alternate section of one prayer praising the Patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac, Jacob) by adding Matriarchs too.

It’s not supposed to be used at this particular service, but a couple women who led services on a rotating schedule snuck it in. Much to my friend Rick’s and my glee. He joked about wanting to write: Minyan, the Musical. Have to decide how reverent or irreverent to be I replied. Yes he said, and some would love it, some hate it. Like so much else in life, I thought.

There’s way more I could describe: the various “honors” during torah reading for one. Early on I got congratulated for pulling the strings to open the torah ark/cabinet. Basically, the only task our ritual director could be sure at that point I wouldn’t flub. One more key detail: I was wearing Cindy remarkable hand knit prayer shawl. Which, of course, many of her friends recognized. Once I made the mistake when taking it off at the service end of holding it to my face: way too emotional to repeat daily. Much more detail I could include, but there’s likely already too much. Ask me if you want more.

I was asked to say a few words on the last day, right before the concluding prayers. I told people I was a most unlikely minyan attendee, etc. Grateful for this and that person’s help and Rebbe Rick’s (joke) guidance and company. Uplifted seeing Cindy’s sisterhood comrades, etc. Hoped in coming months to find an enduring way to honor her memory, etc.

My one specific observation: I had been hearing people recite kaddish at Saturday services off and on for over 60 years. But I’d never given a thought to the brief parts where the congregation joins in on a quick line. Just part of the practice I’d heard without really hearing. Until I was the mourner. Then, on many days when the congregation joined in…

Y’he sh’meh rabbvo m’orach l’olam ulolmey olmayo…

…on many days I felt my heart lifting and a wave of emotional support wash over me. This is why you should say kaddish in a minyan if at all possible. Or I hope in your tradition or life there’s some equivalent thing to bring you comfort when/if you need it. Em and I have been lighting candles at a set time each week also. That works for us too.

The morning group skews old. But I hope that such a group is always there for anyone who needs it. I don’t want to attend any religious services daily. Or weekly. But this is my favorite service. I’ll be back. But on a day they don’t read torah. Forty minutes is plenty.

I decided, too, that on day 30, I would take off my wedding ring. I sensed that if I didn’t tie that act to a ritual I might have a hard time doing it.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Book of Torah Are You?

It is currently the sixth night of Chanukah, and my Chanukah gift to the internet is this quiz to determine what book of the Torah are you!

The Torah, also known as the Chumash and the Five Books of Moses, is much more important than my irreverent quiz might suggest, but this is still fun!!!

Tag your result!

#what book of torah are you#Quiz#am i jewish tumblr#jumblr#jewish texts#Torah#chanukah#happy chanukah

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it’s no great secret that I have a pretty complicated relationship with my Judaism, to the point that it’s gotten me into a fair bit of trouble and it’s gotten me to say some pretty stupid shit. I am, to put it irreverently, a heretic, or just a dumb kid on the internet - that I’m now an adult seems of no consequence in the face of the desolate confusion and alienation I still feel towards my religion, have always felt since I really was a child, have been irrevocably characterized by. such is the scope of my big fat idiot mouth that I hesitate to say anything more, on these topics and on others.

But why the alienation, and what of its kind?

In many respects, it’s probably a common story, so I won’t belabor the point too far: I was raised performatively into my religion - at the behest of a mother I still have a complicated relationship with! - not to believe in it with all my heart, but to find a community and a culture in it, and even back then, I was already too much of a fag and a fuckup to ever fit in with the world that had been presented to me in bits and pieces. My experience with Judaism is a decade of passively absorbing Torah anecdotes that I didn’t even believe in while my peers ignored me or laughed at me for being the little bitch that we all knew I was. C’est la vie.

But if my disconnection from the Jewish religion feels embarrassing, my lingering attachment to it is even worse, because here we come up on the k-word - no, not that k-word. I’m talking about the Kabbalah, and perhaps no element of the Jewish religion is more charged, easily disrespected, or frequently misappropriated. Were I not so wounded in my attachment to Judaism, as it were, I would feel no such need to explore the Kabbalah as I do, and thus have nothing to rationalize, but were I not still ethnically Jewish, I would have no rationalization for it which I could accept. I would have turned back at the gate rather than be another idiot pretending he knew anything whatsoever about a tradition that wasn’t his to claim.

Why am I talking about this now? In part it’s nothing more or less than what it is: a rumination on some of my eclectic traumas and interests. (If you can’t use tumblr as a sounding board in the absence of a therapist or religious leader in your life, what good is it even for?)

But it’s also a disclaimer and a contextualization. Because although I would have no basis otherwise to comment on the appropriation of Kabbalah by various vulgar mystics, I wouldn’t feel confident or honest talking about that appropriation without also contextualizing my own place in that discussion, as someone who may indeed have participated in that appropriation.

Why is the Kabbalah so appropriated as it is, and what is the significance of its appropriation? Why did the Kabbalah catch my eye when the lore of a more mainstream or conventional Judaism could not?

In his Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, Gershom Scholem speaks not as a vulgar mystic but as a dedicated Jew. And yet, although Scholem does not perhaps forgive the vulgar mystic for his trespasses against Jewish lore, Scholem’s profoundly and aggressively historical approach immediately forecloses the possibility that anything else could have come to pass:

The great Jewish scholars of the [1800s] whose conception of Jewish history is still dominant in our days... had little sympathy—to put it mildly—for the Kabbalah. At once strange and repellent, it epitomised everything that was opposed to their own ideas and to the outlook which they hoped to make predominant in modern Judaism...

It is not to the credit of Jewish scholarship that... the greater part of the ideas and views which show a real insight into the world of Kabbalism, closed as it was to the rationalism prevailing in the Judaism of the nineteenth century, were expressed by Christian scholars of a mystical bent.... It is a pity that the fine philosophical intuition and natural grasp of such students lost their edge because they lacked all critical sense as to historical and philological data in this field, and therefore failed completely when they had to handle problems bearing on the facts.

The natural and obvious result of the antagonism of the great Jewish scholars was that, since the authorized guardians neglected this field, all manner of charlatans and dreamers came and treated it as their own property.

Scholem and others similarly contextualize the “great Jewish scholars” in their own time, explaining their steadfast refusal to engage with the mystical discourses of Judaism, but we needn’t concern ourselves with the reasoning of those great scholars here, beyond acknowledging its existence and its essentially reasonable character. (We should by no means imply that the final

“fault” for the appropriation of the Kabbalah by other religious bodies somehow lies with the Jews who dismissed the subject, after all.)

The more important and interesting takeaway here is that this “emergent” mythologization of the Kabbalah by non-Jews is, in fact, not so different in character from the mysticism of the Jews who formulated the Kabbalah in the first place! For Scholem likewise characterizes the formulation of the Kabbalah as, among many other things, a kind of metaphysically (rather than politically) reactionary response to the sterile rationalist discourses of the Judaisms that were predominant at the time: a historically-necessary and inevitable attempt to reclaim the possibility of a mythic theology and a personal (and mystical) experience of God, despite the oppressively transcendental and impersonal formulation of monotheism that held so much more authority. The Kabbalah is implicitly a heretical foil to a more traditional canon - an ecstatic and pre-Othered body of work which always threatens to dissolve and lose all integrity under the immense weight of the purpose it was created to serve. The unleashed spiritual thirst of the deprived devours beyond restraint.

In this respect, there is no strain of Kabbalah which we can isolate, shining and unsoiled, as the thing which was later appropriated by vulgar syncretists, because the Kabbalah itself was always vulgar, and both the creation and the appropriation of the Kabbalah are products of the same human drive for mystical experience. It’s heresy all of the way down! The phone call is coming from inside the house. The genie was always already out of the bottle. Lord English was always already here.

Scholem bitterly appreciates this problem, I suspect, for even in charting the self-destructions of mysticism and in identifying the psychic universality of the mystical experience - the mystic’s unmediated contact with an absolute - he rejects out of hand the notion that mysticisms are fungible, or that our study of mysticism should treat it as infinitely plastic. A Jewish mysticism is not a Christian mysticism, nor are they merely two different forms of some “pure” archetypal mysticism. A mysticism, however transcendental, can neither be divorced from or escape from the historical context that created it. And nor should it, at least in Scholem’s estimation.

So what, then, is the historical context which created the appropriated forms of the Kabbalah that proliferate western esotericism, and how does it still imprison or inform those mysticisms?

Answering such a question with any degree of depth is, at least for now, beyond me... but I wonder, sometimes, whether we can escape from the infinite plasticity and universality of mysticism any more than we can escape from its specificity and boundedness.

Such a dialectic is a thing that Scholem does not speak of, a reach his expertise does not want or need know.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Erasing God's Name

The Talmud says "One must always be careful of wronging his wife, for her tears are frequent and she is quickly hurt."

The husband of the woman suspected of adultery is brought to the Tabernacle. The priest officiating the ritual prepares a cocktail of water and dust from the Tabernacle floor. He makes the woman swear an oath that will bring an imprecation upon herself if she is guilty. Then the priest wrote out the words of the oath on a scroll, washed the ink from the scroll into the water and gave the water to the woman.

The priest shall then write these curses on a scroll, and he shall wash them off into the water of bitterness. (Numbers 5:23)

The woman drank the water, symbolizing the ingesting of the curse to prove her guilt or innocence. If she was guilty, the water would harm her. If she was innocent, the water would have no malignant effect on her. Instead, it would increase her fertility.

The procedure raises a difficulty, though. Ordinarily in Judaism it is forbidden to erase God's holy Name. For example, when a scribe is copying the Scriptures in Hebrew, he can erase any mistake he makes unless it contains God's Name. If he errs while writing a line of text with God's Name in it, he can erase the rest of the line, but not the Name of God.

For this reason, observant Jews do not write the Name of God in Hebrew on a chalkboard or white board that might be erased. Documents containing the written Hebrew Name of God take on a more precious status. They are not carelessly dropped or destroyed or irreverently tossed in the garbage. Holy books containing God's Name are not even left face down on a table or placed beneath other, less sacred books. Holy books are never taken into bathrooms. Even photocopies containing God's Name take on a holy status. When a scroll or book or piece of paper containing God's Name is ready for disposal, the item is accorded a proper "burial" of sorts in a repository for sacred writings. These traditions teach us to respect and revere God's Name.

Given the respect accorded to God's Name and the strong tradition against erasing God's Name, why does the Torah command the priest to erase the curse from the scroll into the water? God's holy Name appears twice in the curse. The sages teach that God is so concerned for peace between a husband and wife that He is even willing for His own Name to be erased to bring it about (Sifre 17).

In Judaism, peace between husband and wife is referred to as shalom bayit (שלום בית), a term that literally means "peace of the house." Peace between a husband and wife takes precedence even over the sanctity of God's Name. If that is the case, we need to be careful about allowing religion to disrupt marriage. God is more interested in the success of your marriage than He is in your particular religious choices. He is so committed to the sanctity of marriage that He is even willing for his Name to be erased to preserve peace in the home. How much more should we make every effort to bring peace into our homes.

The Talmud says "One must always be careful of wronging his wife, for her tears are frequent and she is quickly hurt." The Talmudic passage goes on to say that God is quick to respond to a wife's tears and that her tears are more efficacious than his prayers. God takes the tears of a woman very seriously. The passage concludes by saying, "One must always be respectful towards his wife because blessings rest on a man's home only for the sake of his wife." (b.Baba Metzia 59a)

Shavuah Tov! Have a Good Week!

1 note

·

View note

Text

It has been taught (Niddah, end ch. 3): An oath is administered to him [before birth, warning him]: "Be righteous and be not wicked; and even if the whole world tells you that you are righteous, regard yourself as if you were wicked."

This requires to be understood, for it contradicts the Mishnaic dictum (Avot, ch. 2), "And be not wicked in your own estimation." Furthermore, if a man considers himself to be wicked he will be grieved at heart and depressed, and will not be able to serve G‑d joyfully and with a contented heart; while if he is not perturbed by this [self-appraisal], it may lead him to irreverence, G‑d forbid.

However, the matter [will be understood after a preliminary discussion].

We find in the Gemara five distinct types—a righteous man who prospers, a righteous man who suffers, a wicked man who prospers, a wicked man who suffers, and an intermediate one (Benoni). It is there explained that the "righteous man who prospers" is the perfect tzaddik; the "righteous man who suffers" is the imperfect tzaddik. In Raaya Mehemna (Parshat Mishpatim) it is explained that the "righteous man who suffers" is one whose evil nature is subservient to his good nature, and so on. In the Gemara (end ch. 9, Berachot) it is stated that the righteous are motivated by their good nature,... and the wicked by their evil nature, while the intermediate men are motivated by both, and so on. Rabbah declared, "I, for example, am a Benoni" Said Abbaye to him, "Master, you do not make it possible for anyone to live," and so on.

To understand all the aforesaid clearly an explanation is needed, as also to under-stand what Job said [Bava Batra, ch. i], "Lord of the universe, Thou hast created righteous men and Thou hast created wicked men,..." for it is not preordained whether a man will be righteous or wicked.

It is also necessary to understand the essential nature of the rank of the Intermediate. Surely that cannot mean one whose deeds are half virtuous and half sinful, for if this were so, how could Rabbah err in classifying himself as a Benoni? For it is known that he never ceased studying [the Torah], so much so that the Angel of Death could not over¬power him; how, then, could he err to have half of his deeds sinful, G‑d forbid?

Chapter 1 - Likutei Amarim (chabad.org)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Radius of Sin

So my funny story of this last year is a new concept my SO and I have dubbed the “radius of sin”.

To start with, some back story. My extended family consists of a number of practicing Jews, and unfortunately at the beginning of the pandemic, we lost several family members to COVID. We had two funerals in the course of a month while also sheltering at home and dealing with the consequences of losing our jobs. It was a heartbreaking time.

I was assigned female at birth, so at both funerals, I had to wear a head covering. That’s a typical Jewish tradition for women at the cemetery where my grandparents are buried and for the rabbi who led the services.

In the horror of everything that was happening, I forgot that stupid scarf on both occasions. It just... didn’t happen.

At the first funeral, while we were waiting for the rabbit to decide whether I could participate without the scarf, my SO tried to cheer me up by asking whether I was sinning by showing off my hair to G-d. I mumbled something to the effect of “probably” and they asked me what the radius was.

How far away did I need to be in order to not taint the ceremony with my sin?

(I know this is ludicrous but keep reading.)

Think about the logistics for a moment. What is the radius of sin around a person who is clearly not following the laws and traditions of a given religion? Also, if there is a radius of sin, can we calculate the volume of sin? Will the amount of sin in an area grow the longer a person sins in that vicinity? How does it work if someone else goes above and beyond? What if I sit inside a car, does that count as showing my hair?

Now, please realize that this is completely ridiculous. Also, extremely irreverent. And clearly not the point of giving over loved ones into the arms of the divine.

But that’s sometimes how religion ends up looking: completely ridiculous and meaningless to the participants. Me being at a funeral without a scarf did not demean my grandmother’s long and joyous life. It didn’t take away from her accomplishments (one of which was raising me). It certainly wasn’t some statement about my gender or my relationship with G-d.

But because some rabbi somewhere read a book, suddenly we could ask math questions about theology.