#paul rossler

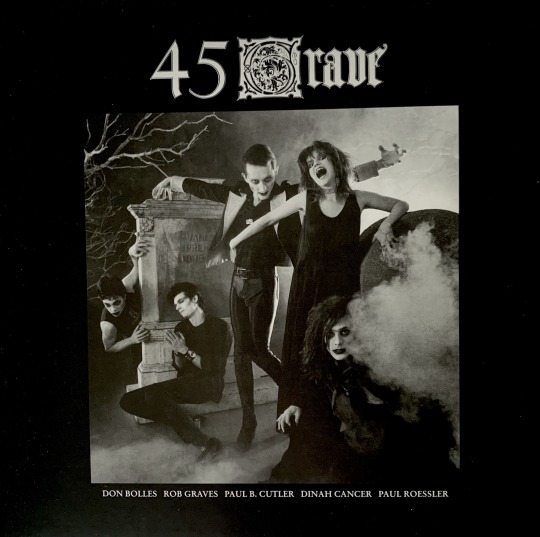

Photo

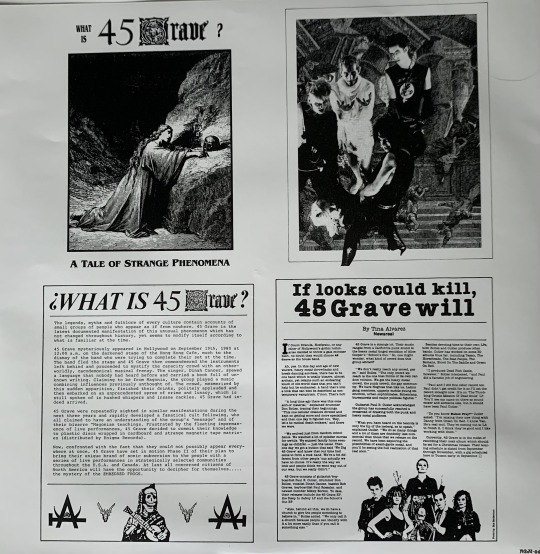

45 grave’s sleep in safety, originally released june 15th, 1983. 2020 limited reissue on green and black marble

#when i say limited i mean like. they made 450.#45 grave#don bolles#dinah cancer#rob graves#paul b cutler#paul rossler#sleep in safety#goth rock#deathrock#vinyl#my vinyl

259 notes

·

View notes

Photo

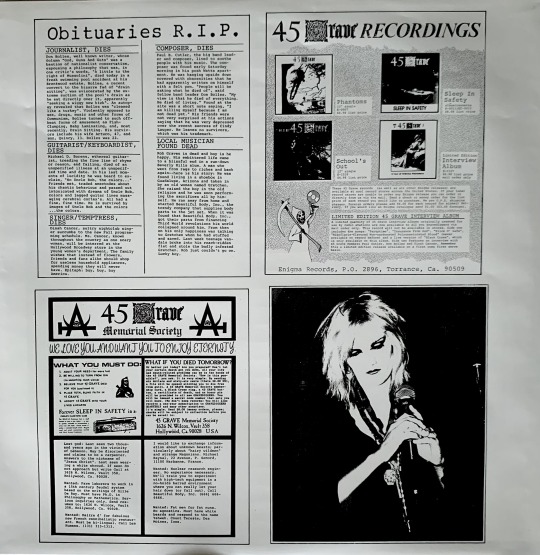

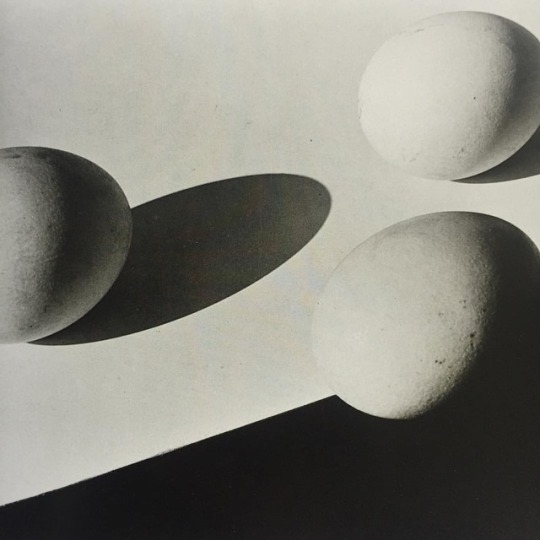

IN THE BOOKSHOP: MOHOLY-NAGY AND THE NEW VISION (1990) Published in 1990, this unique, and rather scarce, catalogue accompanied an exhibition of nearly 100 works by Lazlo Moholy-Nagy and other Bauhaus artists that was held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, July 19-Aug. 28, 1990. Moholy-Nagy and his colleagues (such as Walter Gropius) were advocates of a movement called The New Vision (Neue Optik; Neues Sehen), who sought to move photography from its "landscape" models to an art that could offer new ways of seeing the objective world that was invisible to the human glance. New Vision advocates experimented with unconventional forms and techniques, using unusual angles, new uses of light and shadow, photomontage and collage, etc. This book collects and reproduces a wonderful selection of the works featured in the exhibition fromLaszlo Moholy-Nagy, Aenne Biermann, Paul Citoen, Franz Roh, T. Lux Feininger, Umbo, Walter Peterhans, Karl Straub, Franz Ehrlich, Heinz Loew, Walter Funkat, Herbert Bayer, Katt Both, Edmund Collein, Eugen Batz, Gertrud Arndt, Gyula Pap, Lotte Stam-Beese, Werner Mantz, Jaroslav Rossler. Text in Japanese with captions in English and German. One copy via our new website. 10% off all web orders until midnight tomorrow. #lazlomaholynagy #bauhaus #photography #neueoptik (at WORLD FOOD BOOKS)

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sources, influences, racial politics (ArtsATL) / Glenn Ligon

Since the 1980s, conceptual artist Glenn Ligon has incorporated practices of literature, Abstract Expressionism, photo-based media and appropriation to critically explore issues of identity, politics, sexuality and personal desire, to dazzling effect.

The materials Ligon employs to create his large-scale, often monochromatic works are as varied and textured as the subjects he explores. He moves seamlessly across screen printing, oil paint, white neon painted black and even coal dust, and uses quotations from Gertrude Stein, James Baldwin and comedian Richard Pryor in many of his most widely recognized works.

In 2011, Ligon’s first major mid-career retrospective, “Glenn Ligon: America,” was exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Although drawing comparisons to artists such as Jenny Holzer or even David Hammons is tempting though tenuous, a more precise parallel is to Abstract Expressionists such as Jasper Johns or Robert Rauschenberg, whom Ligon frequently cites as early influences.

The High Museum of Art’s inclusion of Ligon’s 1988 work “There is a consciousness we all have …” in its current exhibition “Fast Forward: Modern Moments” is felicitous. The piece — a relatively small rust-colored work of oil on paper — uses the text from commentary by former High Museum Director Ned Rifkin (then chief curator of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden) in a New York Times write-up on the celebrated sculptor Martin Puryear. The quotation reads, in its entirety: “There is a consciousness we all have that he is a black American artist (by madison ), but I think his work is really superior and stands on its own.” The quote suggests a cultural blindness to which the art world was recently exposed again by way of a series of controversial reviews by Ken Johnson in The New York Times, more than 20 years after Ligon produced the piece.

ArtsATL spoke with Ligon in advance of his artist lecture at the High Museum this Thursday, January 10, at 7 p.m. Following is an edited excerpt of our conversation.

ArtsATL: In the summer of 2011, I went to your retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. It was really interesting to see the progression from some of the earliest works to the current neon “America” works, so I wanted to start off by just talking about that progression a little bit. One of the things I noticed was this shift from the use of color to a lot of black-and-white monochromatic works and then back to color in the mid-to-late 2000s. I’m thinking of those very early more personal works. What caused that shift from more colorful personal works to using other text or to reappropriating text in your work?

Glenn Ligon: With the works that have color in them — the Richard Pryor joke paintings and the coloring book paintings — I think the shift there was in some ways trying to think about color again, because I started out as an abstract painter. So before the text work I was doing abstractions, but they were just abstractions and very involved in color and composition. I decided that that wasn’t the direction in which my work was going.

The Pryor paintings were a way back to color [while] still using text; it allowed me to think about color more but also think about it in relationship to someone like Andy Warhol and his self-portraits from the 1960s. And also it’s just a very simple idea that Richard Pryor needed to be in color.

ArtsATL: The Richard Pryor works are interesting. They are so bright that they’re almost kind of difficult to look at, because if you stare at them too long, they start to kind of vibrate.

Glenn Ligon: Yes, I think, partially, if you look at the Warhol portraits, he’s a master colorist. A lot of combinations have that kind of electrical charge, and their juxtapositions become difficult to look at or obscure the image — that’s what I was interested in. Also because I think Richard Pryor’s a comedian but he’s not funny, so I was really interested in work that made the viewer work to see [it] but was difficult to look at.

ArtsATL: With a lot of your work, you really make the audience work for it. When you [read it] deeply, all of these complications arise. I’m thinking of the text work created with oil stick on just a white background, where the text starts out as this clean line and gradually crescendos into this mass at the bottom of the canvas you can barely read. When I look at this work, it reminds me of music in the sense that you are using a pre-existing phrase, but you are making it your own or replaying it much like a score in your own way. Obviously literature is a big influence in your work, but I wonder if music is anything that you think about as well.

Glenn Ligon: I was just recently at a concert by Steve Reich, and he was talking about some pieces from the ’60s — “Come Out” and “It’s Gonna Rain” — and the use of repeating, out-of-sync human voices. I’d been listening to Reich for years, and I’d never thought about it in terms of my work. Then suddenly I thought, “That’s ridiculous! Why have I never thought about it?” It makes perfect sense. It’s my work, basically.

So it was interesting to think about how music has been important, though it’s not been in the forefront. I did a piece for the pianist Jason Moran for a concert based on Thelonius Monk called “In My Mind.” What he asked me for, or what I thought he asked me for, was something for an album cover or poster, so I took that phrase “In My Mind” and repeated that and made a drawing out of it. When I went to the concert, there was a whole section where that drawing was being projected on the screen behind the musicians and they were playing, as Jason said, to the spaces in the drawing, and using the spaces as pauses.

I thought that was amazing, this relationship to music in the work, although not something I had thought about consciously but something Jason understood. So yes, I think music has been a kind of touchstone, particularly Monk, who I think was influential when I was thinking about making the Richard Pryor paintings, because the playing is so idiosyncratic and so much his own, but absolutely masterful and virtuosic.

I was thinking about that in terms of thinking about Pryor, who can seemingly get up and tell a story, but then realized that Paul Mooney was his writing partner [and] if you listen to different albums they are pursing their material. They changed the jokes to make them more effective. It’s very interesting when you realize he’s not just up there telling stories. There’s a kind of deep back and forth.

ArtsATL: What is it about text that you find so intriguing? I’ve listened to interviews where you’ve talked about your upbringing and how your mother would buy you and your brother books.

Glenn Ligon: Well, I think for a black working-class family, education is the cliché, education was the key, so there’s a lot of emphasis placed on reading and literacy as a sort of way to achieve. Also when I was younger I was interested in writing too, so I think I was more interested in writing than in art.

ArtsATL: Did you ever want to be a writer when you were growing up?

Glenn Ligon: I did, but at some point I realized that writing is as hard as making art, you know? It got to the point where I could make art as a profession; I just thought, “Well, I know lots of artists write,” but I find it as hard. I’ve written a fair amount for magazines, but it’s maybe once a year. We just published a book of writings right around the time of the Whitney show.

I think literature was around in my childhood, and it’s also a place where you’re legitimately allowed to be alone. I grew up in the South Bronx; it was kind of a turbulent neighborhood. I couldn’t justify staying inside all the time unless I was doing something that required being inside. So I think literature became important to me early on.

But I also grew up around appropriation and text. Why write your own when there are texts in the world? Appropriating text is a way of getting certain ideas into the work directly. In a way it’s very straightforward — like, “Oh, I want these ideas in my work; well, just use them.”

ArtsATL: I think a lot about advertising and the work of artists like Hank Willis Thomas, Barbara Kruger or Martha Rossler and this sort of engagement with the idea of being perpetually surrounded by language. It’s how we navigate the world, so I want to ask you about this interaction with public space and your surroundings and how that comes into the work. You’re operating from this very interesting perspective, which is basically you’re in this body, as am I, as an artist, where you are endlessly navigating this idea of being a black artist or being a gay artist or being an American artist, and there are all these things that play into the work in interesting ways.

Could you explain the process of creating “Notes on the Margins of the Black Book,” in which you juxtaposed images of mostly black nude men taken from Robert Mapplethorpe’s “Black Book” with comments about the images collected from people at a bar that Mapplethorpe frequented?

Glenn Ligon: You’re asking a hard question. Specifically with that piece, I just thought that Mapplethorpe was an interesting figure because he was the subject of a big retrospective, also at the Whitney, very celebrated and because he had this body of work that dealt with representations of black men. Because my work wasn’t figurative, I thought it was an interesting project — to use Mapplethorpe’s images as a sort of ready-made material on which to operate.

But instead of defacing it or whatever the impulse would be would seem very simplistic to me, I thought let’s create this context for it. Put the work in the context of all these debates around black male representation, gay sexuality, censorship, AIDS, personal desire. Put all of that next to the work and let the viewers sort it out. And they can choose. They can not read the text and look at the photos or read the text and sort through those issues in the same kind of process that I went through when thinking about that work. It’s just a way to open up that work to a sort of larger context.

Sometimes I think I am interested in that, and sometimes it’s more hermetic. I think I make abstract paintings. They’re text-based but they’re essentially abstract paintings, so in some ways they’re sort of rooted in the specificity of the text I’m using, but in other ways they feel very far from it and it’s the trace of that language [that] is more interesting to me than the specifics of what that language is.

ArtsATL: You’ve mentioned that some of your influences were people like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, who are both Southern artists. Could you talk about that?

Glenn Ligon: It’s probably less about them being from the South, though I think there’s some interesting work on Rauschenberg’s paintings from the ’50s which I love: “The Black Paintings” and “The White Paintings.” There’s a historian, Mignon Nixon; I think she is actually from the South and she’s at the Courtauld [Institute of Art] now. She did some work on Rauschenberg’s “Black Paintings” and was asking, “Well, if you look at what was on the covers of those papers at that time, it was all about civil rights groups.”

I don’t know what he made of that or what importance that takes, but I think it is interesting to think about how work that is seemingly not about something can be about something. But I think I was interested in Johns and Rauschenberg — I think more in Johns because of the use of language, but now increasingly in Rauschenberg — because I’m very fascinated with how he made images work and with decontextualizing very familiar images. Johns, too, you know [American flags] and all of that, but also because they were painters, and I gravitated more towards them than I did towards Barbara Kruger or Joseph Kosuth. I wanted to remain a painter, and they provided certain kinds of models. Someone like Kosuth or Kruger provided certain kinds of relationships to theory and appropriation and critique of consumer culture, so I was trying to walk the line between those.

ArtsATL: Because your work is so closely connected to language and is also often connected to American history, I want to ask about context. I’m thinking about James Baldwin’s Stranger in the Village, which you’ve also referenced in your work. How do you feel that your work changes in different environments? What are the responses to your work outside the United States?

Glenn Ligon: Well, I had a funny sort of encounter. I had a year-long fellowship in Berlin in 2000, and I was making work for Documenta that Okwui Enwesor curated, a body of paintings based on Stranger in the Village. I had an interview with [American critic] Blake Gopnik, who was doing an article about American artists living overseas. He came and picked my brain and then when I got the article it said, “Glenn Ligon’s issues don’t translate in European context.” And I thought, “Well, James Baldwin? Stranger in the Village … what doesn’t translate?” I thought that was fascinating, this kind of blindness or the inability to extend the reading of a text from a different era to a present situation.

I have a show coming up in Japan in March, and one of the neon works I was thinking about using is one that says “negro sunshine,” which is from Gertrude Stein. I asked the curator if she could find the Stein book that it’s from and tell me what the translation is into Japanese. And she said, “Well, it’s not so good. It’s ‘the sunshine of black people,’ ” and I thought that was great. It’s fascinating, but it loses the specificity of the word “negro,” a word in American context that evokes a particular time period.

That kind of slippage is really interesting. It’s not something I’ve worked with extensively — most of the work I’ve done has been in English — but it is an area that I’m thinking more about exploring. But it’s tricky, because one has to sort of dive into a language that’s not your own or trust people’s interpretations.

ArtsATL: Right. It is really tricky. It’s also interesting, this sort of discomfort you feel with not being entirely fluent in a language and having to trust somebody to translate for you.

Glenn Ligon: I guess also it’s trying to understand what kind of cultural presuppositions come out of thinking about translation. That word “negro” is not really translatable into Japanese, and so it’s “black people.” Why didn’t they just leave it? If you can’t translate it, just leave it. So I found that all kind of fascinating; whether I can work with that as material, I don’t know. It’s increasingly interesting to me as I start to show in places outside the United States.

ArtsATL: I want to talk about the very beginning of your career. I just turned 29, which is right around the age you were when you received your New York Foundation for the Arts grant. Could you talk a little bit about that transition? I know you were working; you had a “day job” and then you got this grant and it freed up time that allowed you to become a full-time artist.

Glenn Ligon: My mother joked that the day I knew I was an artist was when the government said I was an artist. The NYFA doesn’t trust artists with individual grants any more — they now have to be administered through a handler — so this was back when the government would actually send you a check. I just decided it was a moment where I could try to be a full-time artist for a while.

I don’t remember the amount of the grant, but it was enough to take some significant amount of time off from work, and I thought, “Well, what does it mean if I start working full time or try to have a proper studio?,” because I was working out of a basement in my house. So that was a huge, huge shift — I guess that was in ‘89 — and I had just started to show, a few works were selling. It just became this sort of launch pad for this thing called “being an artist” which I was already doing, which I was just sort of doing part time and kind of decided to do it full time then.

ArtsATL: It’s really interesting, because very rarely do I get the opportunity to hear artists talk about that progression or that jump between working in your basement, or your mother’s basement, and then suddenly becoming a full-time successful artist.

Glenn Ligon: Well, also I didn’t go to graduate school, so it took me a long time to get a working practice. . . . I never had two years where all you had to do was be in your studio.

ArtsATL: I read somewhere recently that you’re working on a piece based on Walt Whitman’s work.

Glenn Ligon: Yeah, it’s a big neon piece for the New School. It’s going to be in the student center in the new building they’re making.

ArtsATL: What made you choose Whitman for this project?

Glenn Ligon: Well, I think because the New School has such a history of social engagement. It was started by refugees from Europe during the ’30s, and not started by but stocked with refugees from Europe. There are some very famous Orozco murals there that were illustrating the history of Communism basically, that are kind of fantastic, and they also collect widely and exhibit work in their various buildings. So I just thought that the history of the New School was about a certain kind of populism, and it would be interesting to think about some author who embodied that. The piece concentrates on Leaves of Grass, more specifically on the city as subject matter and thinking about bodies and how one encounters bodies in the city and desiring those bodies. So essentially it’s a big piece about cruising in the student cafeteria. I don’t think they know that.

Source: ArtsATL.

Link: Sources, influences, racial politics

Illustration: Glenn Ligon [USA] (b 1960).

'Warm Broad Glow (reversed)', 2007.

Photogravure and aquatint on Somerset paper

(62 x 90 cm).

Moderator: ART HuNTER.

#art#contemporary art#glenn ligon#conceptual art#article#interview#brainslide bedrock great art talk#artsatl

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Burning Ship Fractal [はてなブックマーク]

Burning Ship Fractal

"Burning Ship" fractal Written by Paul Bourke Previously described by Michael Michelitsch and Otto Rossler The images described here are generated by analysing the following series for each point (cx,cy) on the plane. The grey level assigned to each point (cx,cy) is determined by how fast the ser...

from kjw_junichiのはてなブックマーク http://bit.ly/1JVXYcC

0 notes

Text

Single Review: An Adolescent Tragedy - "Despondent (The Great Unknown)"

Folk-punk is my whole heart, undoubtedly. I tote hardcore and straight punk quite a lot, but when I hear something that genuinely makes me cry real tears, folk-punk is always the cause. I received a song of this flavor in my inbox tonight that did just that, and I’m so unbelievably pleased to share it with all the readers here at DRM.

An Adolescent Tragedy is made up of Ross Everitt and his guitar. In traditional folk-punk style, the track is wrought with lyrics detailing some of life’s greatest tragedies with a bit of sarcasm and wit in almost-too-personal detail. Artists like Pat The Bunny and Erik Petersen of Mischief Brew come to mind, which is incredibly fitting because the latest release from An Adolescent Tragedy is being worked on by Paul Rossler who did the last Pat The Bunny album. I hear familiarities between Everitt and Kyle Trocolla as well, another favorite of mine.

What I appreciate about Everitt’s project is how close to home this particular track hits — his brother David passed away from a heroin overdose in January 2016, and his passing pushed Ross on a downward spiral which found him spending more time in jail cells, rehabs, and psych wards than the great outdoors. His use of tone and delivery is sharp and without filter; it’s a track that will strike you from the first note to the last.

Additionally, Ross’ voice is clear and pristine and I just really love when I don’t have to look up the lyrics to a song in order to understand what the singer is saying. The song is well-recorded and clear-cut — the lyrics are truly despondent, hence the title. There’s nothing I love more than an honest, open-hearted song that hits a listener with some truth and certainty: Nothing in this life is ever assured.

"I always say ‘Thank god for drugs and alcohol' because it saved my life,” Everitt says. "Not in the sense most people think, but I was thinking about suicide and they were a solution for me for a while… until they weren’t and I lived my early twenties in jail or psych-wards or rehab. I thought the system was my problem for a long time, the cycle of jails and rehabs or the government or God and even if I eventually bought into what I thought was expected of me like go to school get a real job and settle down, it would lead me into a life of materialism resentment and sensory input... things I never really wanted.”

Listen to “Despondent (The Great Unknown)” below and be on the lookout for when An Adolescent Tragedy drops their latest album.

youtube

Listen to An Adolescent Tragedy on Spotify and Bandcamp.

Catherine Dempsey may have just found her new favorite folk-punk artist. You can follow her on Instagram and Twitter.

Follow DRM on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Subscribe to the DRM YouTube channel.

#an adolescent tragedy#catherine dempsey#album review#ross everitt#folk punk#folk-punk#punk#punk rock

0 notes

Video

A song written by a good friend of mine named Paul Rossler. This song is called "The W". Written about a buisness trip to Austin TX. And a stay at The W. #whotel #thewhotel #austintx #oklahomamusic #reddirtmusic #diffidentrebel #hamboneproductions #tulsamusic #tulsamusicscene (at Austin, Texas)

#oklahomamusic#tulsamusic#austintx#thewhotel#diffidentrebel#hamboneproductions#tulsamusicscene#reddirtmusic#whotel

0 notes

Photo

IN THE BOOKSHOP: MOHOLY-NAGY AND THE NEW VISION (1990) Published in 1990, this unique, and rather scarce, catalogue accompanied an exhibition of nearly 100 works by Lazlo Moholy-Nagy and other Bauhaus artists that was held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, July 19-Aug. 28, 1990. Moholy-Nagy and his colleagues (such as Walter Gropius) were advocates of a movement called The New Vision (Neue Optik; Neues Sehen), who sought to move photography from its "landscape" models to an art that could offer new ways of seeing the objective world that was invisible to the human glance. New Vision advocates experimented with unconventional forms and techniques, using unusual angles, new uses of light and shadow, photomontage and collage, etc. This book collects and reproduces a wonderful selection of the works featured in the exhibition fromLaszlo Moholy-Nagy, Aenne Biermann, Paul Citoen, Franz Roh, T. Lux Feininger, Umbo, Walter Peterhans, Karl Straub, Franz Ehrlich, Heinz Loew, Walter Funkat, Herbert Bayer, Katt Both, Edmund Collein, Eugen Batz, Gertrud Arndt, Gyula Pap, Lotte Stam-Beese, Werner Mantz, Jaroslav Rossler. Text in Japanese with captions in English and German. One copy via our new website. 10% off all web orders until midnight tomorrow. #lazlomaholynagy #bauhaus #photography #neueoptik (at WORLD FOOD BOOKS)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

IN THE BOOKSHOP: MOHOLY-NAGY AND THE NEW VISION (1990) Published in 1990, this unique, and rather scarce, catalogue accompanied an exhibition of nearly 100 works by Lazlo Moholy-Nagy and other Bauhaus artists that was held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, July 19-Aug. 28, 1990. Moholy-Nagy and his colleagues (such as Walter Gropius) were advocates of a movement called The New Vision (Neue Optik; Neues Sehen), who sought to move photography from its "landscape" models to an art that could offer new ways of seeing the objective world that was invisible to the human glance. New Vision advocates experimented with unconventional forms and techniques, using unusual angles, new uses of light and shadow, photomontage and collage, etc. This book collects and reproduces a wonderful selection of the works featured in the exhibition fromLaszlo Moholy-Nagy, Aenne Biermann, Paul Citoen, Franz Roh, T. Lux Feininger, Umbo, Walter Peterhans, Karl Straub, Franz Ehrlich, Heinz Loew, Walter Funkat, Herbert Bayer, Katt Both, Edmund Collein, Eugen Batz, Gertrud Arndt, Gyula Pap, Lotte Stam-Beese, Werner Mantz, Jaroslav Rossler. Text in Japanese with captions in English and German. One copy via our new website. 10% off all web orders until midnight tomorrow. #lazlomaholynagy #bauhaus #photography #neueoptik (at WORLD FOOD BOOKS)

0 notes

Photo

NEW IN THE BOOKSHOP: MOHOLY-NAGY AND THE NEW VISION (1990) Published in 1990, this unique, and rather scarce, catalogue accompanied an exhibition of nearly 100 works by Lazlo Moholy-Nagy and other Bauhaus artists that was held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, July 19-Aug. 28, 1990. Moholy-Nagy and his colleagues (such as Walter Gropius) were advocates of a movement called The New Vision (Neue Optik; Neues Sehen), who sought to move photography from its “landscape” models to an art that could offer new ways of seeing the objective world that was invisible to the human glance. New Vision advocates experimented with unconventional forms and techniques, using unusual angles, new uses of light and shadow, photomontage and collage, etc. This book collects and reproduces a wonderful selection of the works featured in the exhibition fromLaszlo Moholy-Nagy, Aenne Biermann, Paul Citoen, Franz Roh, T. Lux Feininger, Umbo, Walter Peterhans, Karl Straub, Franz Ehrlich, Heinz Loew, Walter Funkat, Herbert Bayer, Katt Both, Edmund Collein, Eugen Batz, Gertrud Arndt, Gyula Pap, Lotte Stam-Beese, Werner Mantz, Jaroslav Rossler. Text in Japanese with captions in English and German. Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Aenne Biermann, Paul Citoen, Franz Roh, T. Lux Feininger, Umbo, Walter Peterhans, Karl Straub, Franz Ehrlich, Heinz Loew, Walter Funkat, Herbert Bayer, Katt Both, Edmund Collein, Eugen Batz, Gertrud Arndt, Gyula Pap, Lotte Stam-Beese, Werner Mantz, Jaroslav Rossler. One copy in the bookshop and via our website. #worldfoodbooks #lazlomoholynagy #bauhaus #photography (at WORLD FOOD BOOKS)

0 notes

Photo

NEW IN THE BOOKSHOP: MOHOLY-NAGY AND THE NEW VISION (1990) Published in 1990, this unique, and rather scarce, catalogue accompanied an exhibition of nearly 100 works by Lazlo Moholy-Nagy and other Bauhaus artists that was held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, July 19-Aug. 28, 1990. Moholy-Nagy and his colleagues (such as Walter Gropius) were advocates of a movement called The New Vision (Neue Optik; Neues Sehen), who sought to move photography from its “landscape” models to an art that could offer new ways of seeing the objective world that was invisible to the human glance. New Vision advocates experimented with unconventional forms and techniques, using unusual angles, new uses of light and shadow, photomontage and collage, etc. This book collects and reproduces a wonderful selection of the works featured in the exhibition fromLaszlo Moholy-Nagy, Aenne Biermann, Paul Citoen, Franz Roh, T. Lux Feininger, Umbo, Walter Peterhans, Karl Straub, Franz Ehrlich, Heinz Loew, Walter Funkat, Herbert Bayer, Katt Both, Edmund Collein, Eugen Batz, Gertrud Arndt, Gyula Pap, Lotte Stam-Beese, Werner Mantz, Jaroslav Rossler. Text in Japanese with captions in English and German. Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Aenne Biermann, Paul Citoen, Franz Roh, T. Lux Feininger, Umbo, Walter Peterhans, Karl Straub, Franz Ehrlich, Heinz Loew, Walter Funkat, Herbert Bayer, Katt Both, Edmund Collein, Eugen Batz, Gertrud Arndt, Gyula Pap, Lotte Stam-Beese, Werner Mantz, Jaroslav Rossler. One copy in the bookshop and via our website. #worldfoodbooks #lazlomoholynagy #bauhaus #photography #franzroh (at WORLD FOOD BOOKS)

0 notes

Photo

NEW IN THE BOOKSHOP: MOHOLY-NAGY AND THE NEW VISION (1990) Published in 1990, this unique, and rather scarce, catalogue accompanied an exhibition of nearly 100 works by Lazlo Moholy-Nagy and other Bauhaus artists that was held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, July 19-Aug. 28, 1990. Moholy-Nagy and his colleagues (such as Walter Gropius) were advocates of a movement called The New Vision (Neue Optik; Neues Sehen), who sought to move photography from its “landscape” models to an art that could offer new ways of seeing the objective world that was invisible to the human glance. New Vision advocates experimented with unconventional forms and techniques, using unusual angles, new uses of light and shadow, photomontage and collage, etc. This book collects and reproduces a wonderful selection of the works featured in the exhibition fromLaszlo Moholy-Nagy, Aenne Biermann, Paul Citoen, Franz Roh, T. Lux Feininger, Umbo, Walter Peterhans, Karl Straub, Franz Ehrlich, Heinz Loew, Walter Funkat, Herbert Bayer, Katt Both, Edmund Collein, Eugen Batz, Gertrud Arndt, Gyula Pap, Lotte Stam-Beese, Werner Mantz, Jaroslav Rossler. Text in Japanese with captions in English and German. Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Aenne Biermann, Paul Citoen, Franz Roh, T. Lux Feininger, Umbo, Walter Peterhans, Karl Straub, Franz Ehrlich, Heinz Loew, Walter Funkat, Herbert Bayer, Katt Both, Edmund Collein, Eugen Batz, Gertrud Arndt, Gyula Pap, Lotte Stam-Beese, Werner Mantz, Jaroslav Rossler. One copy in the bookshop and via our website. #worldfoodbooks #lazlomoholynagy #bauhaus #photography #walterpeterhans (at WORLD FOOD BOOKS)

0 notes