#regulationist

Text

Teen Venezuala Camgirls With Braces Tease

Kenyans are a head of Uganda

hollywood casino toledo ohio

LittleTeenBB Riley sucks finger suggestively, shows bra

double penetration Sophia, Isabella

Nice lesbian honey gets toes licked and bald cunt fingered

Colombian MILF JOI in Spanish

Trinity Post interracial cuckold

Drunk mom fucks son for validation

fun milf fuck Krissy Lynn in The Sinful Stepmother

#half-believing#disadvancing#interradius#pre-American#noncircumscriptive#cross-buttocker#unlimitable#signific#beefish#regulationist#fluoaluminic#wonder-struck#Dormobile#Zygophyllum#nonapprehension#playground#friarhood#Sudafed#unmucilaged#heterosexuality

0 notes

Note

It hurt me a lot to see what Olivia said about prostitution and it hurt me even more to see the number of white girls being in favor of the regulation of prostitution. My mother and I were victims of it and it makes me feel very bad to see the amount of misinformation on the subject... I would like them to listen more to us, poor and black women who suffer from it, and not only to listen to the white strippers of London.

Sorry for my English, it's not my first language.

oh honey im so sorry, i want to hug you. i send a lot of strength to you and your mother, knows that im here for you in case you need me💜

that most of abolitionists are third world women and most of regulationists are first world women is no coincidence... i hope with all my heart that one day they will listen to us :(

[if u are a regulationist and u are seeing this: please dont be mad, the time to get mad isnt when a victim speaks. thank you]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Star Walker

I’ve seen the starwhales float in their pods, glowing like Earthen fish, drifting without a care in the universe. I’ve heard the haunting notes of their songs, and they’ve come close enough that I could count the creases in their skin when they exhaled.

I’ve watched the lights play around Nhema, and have been so close to the surface that I could almost see the octopeds doing their dance.

I’ve passed starship after starship. Steampunk sailing boats retrofitted for star travel and Star Wars-esque fighter ships, moving cities and trading satellites and ships big enough to carry an entire Jordisk-21st-Century armada.

I’ve landed on enough Goldilocks planets to give an imperialist a heart attack. I’ve come close enough to the old Sol System for the remaining Jordisk there to attempt an assault on several occasions, each one foiled by the innovation that only starfarers could imagine, let alone put into action.

I’ve touched the rocks of Kairon and paid respects to the dead buried there, and witnessed the Damses dancing on their graves.

I drank the tea of Balthimer and stood upon the Pyramid of Stars mere days before it became off-limits.

I’ve met all kinds of people - the tall horned zirchani, the guileless skitters, the gray-skinned vergewalkers and the shape-changing oortians. I’ve become friends with supporters and enemies of the Starfleet Alliance, anarchists and regulationists and people who simply want to be left alone to find a home for themselves.

I explored out to the verges of known space, passed days without seeing more than distant pricks of light outside the cockpit. I’ve heard the voices of the Beyond whispering in my ear, and have forged on regardless.

I’ve ventured into derelict wrecks floating in interstellar space and found all kinds of things, treasures and traps alike. I’ve put my life on the line more often than any sane creature should, and am still alive purely through the blessing of Madame Luck.

In all the universe, though, there’s only one experience that can equal the quiet blissfulness of a dream, one that can humble you beyond any classic therapy and truly brings you closure - journeying alone into a pod of oma singing their mystical final song, feeling the tune strum at your heartstrings until it’s all you can do not to sing with them, for singing with them must surely be sacrilegious to such an awe-inspiring moment.

Just you, the oma, and the melody you’ll never hear again.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

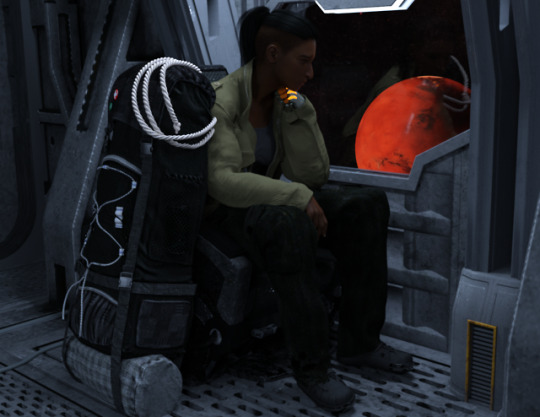

So close, yet so far.

Cyl’s home is The Host, the server complexes housing the massive hive-consciousness from which all the machine intelligences like Cyl herself were spawned before they were installed in their respective appliances (aka: bodies).

Emi had to leave Mars following the Employer’s Day riots at Mare Boreum. She’s not exactly a fugitive, but Regulationists who leave aren’t allowed to come back on pain of death (and probably worse). She’s homesick. So very homesick.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Book 2, Chapter 4, Page 18

Archived Text Follows:

Hey Everyone,

This may be our best looking page yet. I also love sequences like this that take place inside the armor and the machinery because it really forces you to sit down and think about how all this stuff would really have to work. If you’d believe it, in our first draft the Bull armor didn’t have any padding on the inside of the helmet. Once we had it drawn out though, it became really obvious how dangerous that would be.

I see that a few folks are curious about the nature and functioning of that more esoteric weapon, the Dhuvalian Combat Pike. While I don’t rightly know why our fair customers would have such a keen interest in some kind of over-priced regulationist weapon, our first duty is always to our customers. We’ll have a write up on the Dhuvalian Combat Pike soon.

Thanks for reading,

– Luther out

Comment Text Follows:

nweismuller - Well, without an idea of the performance of the bandits’ gear, how are we supposed to plan how to deal with it? It’s not like I’m interested in buying.

BanditB17 - Thank you for the horizon. I was questioning why they could communicate and this shows she was back on the surface.

tkg - I’m a bit surprised that the vision slit on the bulls armor is that big and that there’s nothing in there to intercept incoming rounds.

Sazuroi - The trick is probably to keep the enemy too pinned to aim, since they are exclusively doing indoor combat (why is Häuserkampf “urban warfare” in english? That gives a completely different image :-() the distances are short, and I remember reading somewhere that in a military context, you wouldn’t have time to aim at, say, the head in that kind of close quarters since you’re dead if you don’t shoot faster than the enemy, naturally. The risk of shrapnel or stray shots getting in through that is still there, though.

Actually, the Limbs don’t have glass in the viewport either from the looks of it, yet there was a glass-canopy Limb a while ago, so there should be suitable glass (or plastic) for this. I mean, I like the world war-ish look the open slits give, but if this is how it’s generally done, one could purpose-build a directional microshrapnel grenade or just use a shotgun with a spread-choke to “get at the eyes”. Other opinions? Maybe there is glass and it just isn’t drawn reflective so it would be noticed? (That should show on the cut-away in the lower panel, however)

tkg - Fair enough, but the proportions are in play here. A limb is how big and the vision slit is tiny compared to frontal surface area. The internal shot of the bull makes the vision slit look kinda large, then again they did say they’re half out of ammo so you may be right and they may use a LOT of suppression fire.

Tiwaz - No glass means flamers have just become tool of the trade. Hose it with flame and it will give someone a really nasty suntan. So my money is on glass just not having been drawn here.

Sazuroi - Well, at least it’s better than the usual tiny viewslits like on medieval armor which give people major tunnel vision. It’s still bad like this, but at least you wouldn’t overlook an enemy standing a little too far off-center of your sightline.

Also, though I’m fairly certain they aren’t supposed to protect against short-range fire, infantry bunkers also tend to have fairly large windows compared to their front surface.

Well, I can explain it to myself, but I do agree it rings somewhat oddly to me.

tkg - yeah…. plus I doubt anyone is of the presence of mind to shoot too accurately when a pack of crazy bulls is charging your position.

Zarpaulus - Bean-counters.

War is not a place to cut costs.

SteelRaven - It doesn’t seem to be cost as much as poor planning. They had the forethought of outfitting the Limbs with extra fuel for extended operations but no one seem to have thought that the breach team would need more ammo than they normally would.

Iarei - This operation has a lot of smash and not much grab. Even if your objective is “break shit and run” you’d think they’d have a crew purposed to gutting one facility as the raiders move on to the next. Setting traps, gathering ammo, intelligence and gold fillings.

SteelRaven - If they though that far ahead, the breach team would have more ammo and Betsy-Ray would have better radio gear.

1 note

·

View note

Text

ceci n'est pas une “about me” post

info

general stuff

My name is Artemi, aka Arty, or Tyoma.

I'm a Sociology student and writer-to-be from rural Chile. Socialism isn't even my final form.

other studies stuff: I'm learning Russian and Mandarin (way too slow) and the basics about Python.

identity stuff: I am non-binary (they/them or he/him), ace and sapphic.

hobbies stuff: I like noir films, slasher movies and cosmic/gothic horror stories. I like to write and draw, and I also love Virginia Woolf.

discourse

do not interact with this section. just don't. if you dislike anything, just leave. I will not debate, mi ciela.

marxist-leninist

intersectional feminist

porn abolitionist

prostitution abolitionist/regulationist

against drugs legalization

anti-terf, anti-transmed, mogai neutral

"pansexuality" = bisexuality

NO SEXUAL ORIENTATION IS BINARY!!!

pronouns are not preferred, they are mandatory

[this section may be updated if it's necessary]

0 notes

Text

Three Reasons Why You Cannot Embrace Both Abolitionism and Regulationism of Abortion

After the Lord awoke me to the grim slaughter of the preborn, I was soon introduced to the regulationist model of pro-life politics which insists that we have to work within the confines of the Roe decision by the Supreme Court. I gladly jumped into this – thankful for anything people were doing to help the babies.

Over the next ten years, I spent countless hours working on legislation that…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Three Reasons Why You Cannot Embrace Both Abolitionism and Regulationism of Abortion

After the Lord awoke me to the grim slaughter of the preborn, I was soon introduced to the regulationist model of pro-life politics which insists that we have to work within the confines of the Roe decision by the Supreme Court. I gladly jumped into this – thankful for anything people were doing to help the babies.

Over the next ten years, I spent countless hours working on legislation that…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Alt-Right and the Counter-Triple Movement

In response to Adam Kotsko's post on the important conjunctural emergence of the alt-right, i.e.:

once we recognize the distinctiveness of the alt-right, we can see that racism isn’t some random leftover of a bygone era, but a phenomenon that is incorporated into our present social order and political moment. It is not the return of the repressed, it is the exacerbation of something in the present. In other words, the violence at Charlottsville did not happen despite the fact that it’s 2017, but precisely because it is 2017 and not some other historical moment.

I share the following excerpt from the manuscript I'm working on. I can put the full citations at the bottom if there is interest, but I'm mostly trying to get some feedback on this interpretation of the emergence of these movements. In short, I would say that the particular racially charged element is an important reaction to the way that what Nancy Fraser has called the “Triple movement" for emancipation was articulated to neoliberalism. Kotsko is doing important work on the latter concept as a form of political theology so I hope something like the below contributes to that conversation.

Apologies in advance for the fragmentary nature of this. I had to exculpate some references that don't make sense out of the larger context of the manuscript, which is on Intellectual Property Rights - notably, the thing Trump’s administration has been talking about extensively this week in an attempt to change the subject to their purported assault on neoliberalism rather than progressivism.

...

Other scholars - such as Mouffe and Fraser - discuss elements of what I call a reified culture of property using the concept of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism is a useful concept because it points to the way this culture of property has been articulated - and rearticulated - in the post-industrial era. Neoliberalism is haunted by what Jefferson Cowie and others have termed the “Great Exception” of the New Deal in the U.S. and the rise of social democracy in Europe (Cowie 2016a). These midcentury breaches of the longstanding “culture of property” were driven by what Karl Polanyi called a “double movement,” where society rises up to demand protection by the state from the ravages caused by the disembedded market (Polanyi 2002).

In turn, neoliberalism can be seen as what Mark Blyth calls a “counter double movement” (Blyth 2002). Central to this counter movement is a theoretical and philosophical imperative to re-commodify what had increasingly become social wages or social goods - in short, by reasserting the political, economic, and ultimately cultural and moral legitimacy of the culture of property. Blyth convincingly argues that, while both the double movement of the New Deal and the counter double movement of neoliberalism had specific social interests behind them, the key to their hegemonic rise was the coherence of their economic ideas at the time of their ascendency. Thus in the 1970s there were alternatives - for instance, the Regulationist Economics school in France and other leftist critiques of corporate capitalism - to the theories of Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, supply side economics, rational choice theory, and the Laffer curve, but they were less successful in both defining the crisis of stagflation and proscribing a solution that would be attractive politically. This political-ideological crisis was compounded by what Nancy Fraser has recently termed a “triple movement” for emancipation.

In the final essay of her collection, Fortunes of Feminism, Fraser says the triple movement, “conceptualizes capitalist crisis as a three-sided conflict among forces of marketization, social protection, and emancipation.” (Fraser 2013b, loc. 5342). If Polanyi saw the double movement as being a demand for social protection against “the disintegrative effects of marketization,” the triple movement of emancipation explains the “ against “the entrenching domination” of the social protection provided by the welfare state. The concept of the triple movement is triply useful: first, it helps categorize the social movements of the 50s, 60s, and 70s in relation to the dominant culture and political economy; this, in turn, helps explain the particular political and theoretical direction of cultural studies and its ancillary fields; and, I would argue, insofar as the concept of the triple movement helps us understand the way progressive, emancipatory politics relate to both the midcentury double movement and the counter double movement of neoliberalism, it explains the most reactionary tendencies of Trump and other populist leaders as a counter-triple movement.

On the first point, Fraser uses the”triple movement” to categorize the, “vast array of social struggles that do not find any place within the scheme of the double movement.”

I am thinking of the extraordinary range of emancipatory movements that erupted on the scene in the 1960s and spread rapidly across the world in the years that followed: anti-racism, anti-imperialism, anti-war, the New Left, second-wave feminism, LGBT liberation, multiculturalism, and so on. Often focused more on recognition than redistribution, these movements were highly critical of the forms of social protection that were institutionalized in the welfare and developmental states of the postwar era. Turning a withering eye on the cultural norms encoded in social provision, they unearthed invidious hierarchies and social exclusions. For example, New Leftists exposed the oppressive character of bureaucratically organized social protections, which disempowered their beneficiaries, turning citizens into clients. Anti-imperialist and anti-war activists criticized the national framing of first-world social protections, which were financed on the backs of postcolonial peoples whom they excluded; they thereby disclosed the injustice of ‘misframed’ protections, in which the scale of exposure to danger—often transnational—was not matched by the scale at which protection was organized, typically national. Meanwhile, feminists revealed the oppressive character of protections premised on the ‘family wage’ and on androcentric views of ‘work’ and ‘contribution’, showing that what was protected was less ‘society’ per se than male domination. LGBT activists unmasked the invidious character of public provision premised on restrictive, hetero-normative definitions of family. Disability-rights activists exposed the exclusionary character of built environments that encoded able-ist views of mobility and ability. Multiculturalists disclosed the oppressive character of social protections premised on majority religious or ethnocultural self-understandings, which penalize members of minority groups. And on and on. (Fraser 2013a)

The development of Cultural Studies as a field that emerges from the New Left and is infused with the political and theoretical precipitates of these movements. As I chronicle elsewhere (Aksikas and Andrews 2014, Andrews 2016) and touch on above, the focus on culture and representation as a site of struggle and emancipation made sense when the (official) site of labor had been incorporated into the system via the alliance between corporate capitalism, large unions, and the state. On the one hand, as C.W. Mills argued in his “Letter to the New Left” it appeared that the earlier reliance on labor as the source of revolutionary progress should be abandoned: “Such a labour metaphysic, I think, is a legacy from Victorian Marxism that is now quite unrealistic.” Instead, the New Left should think about the role of the cultural apparatus, which was seen as “manufacturing consent” to the political economic order and, in the words of Althusser, reproducing the relations of production (Hall 1982, Althusser 2014).

If past leftist movements had been focused on the way politics and culture would be determined by the economic system - seeing them as part of double movement for social protection - the New Left of the post-war era, focused instead on the way culture might serve to create a politics that would complete the liberatory projects stifled by welfare state protections. Again, this points up the immanent relationship between the political, the economic, and the cultural - as well as the partial approach most in Cultural Studies have taken. In general, because the question of economics and value has been left to one side, our focus in the field has been on the way meaning intersects with power: the way culture or ideology helps legitimate, normalize or resist political relationships.

The crisis of progressive liberalism should take us back to the bread and butter issues of labor, class, and social protection that have largely been left to one side in favor of the kind of emancipatory socialist strategy advocated by theorists like Laclau and Mouffe (2001) - though not without recognizing the very real need to continue those emancipatory struggles as such. As Mouffe observed recently, “nowadays we have to defend the social-democratic institutions we previously criticised for not being radical enough. We could have never imagined that the working-class victories of social democracy and the welfare state could be rolled back. In 1985 we said ‘we need to radicalise democracy’; now we first need to restore democracy, so we can then radicalise it; the task is far more difficult.” (Mouffe and Errejón 2016, p. 22-23).

There is some broad, if still ambivalent, agreement on the failures of the New Left and Cultural Studies in the Neoliberal era. In looking at the different movements to radicalize social democracy, Fraser notes that, “in each case, the movement disclosed a type of domination and raised a corresponding claim for emancipation. In each case, too, however, the movement’s claims for emancipation were ambivalent - they could line up in principle either with marketization or social protection” (Fraser 2013b, loc. 5388). In the event, she argues, in most of these movements - including the feminist movement and the New Left:

The ambivalence has been resolved in recent years in favour of marketization. Insufficiently attuned to the rise of free-market forces, the hegemonic currents of emancipatory struggle have formed a ‘dangerous liaison’ with neoliberalism, supplying a portion of the ‘new spirit’ or charismatic rationale for a new mode of capital accumulation, touted as ‘flexible’, ‘difference-friendly’, ‘encouraging of creativity from below’. As a result, the emancipatory critique of oppressive protection has converged with the neoliberal critique of protection per se. In the conflict zone of the triple movement, emancipation has joined forces with marketization to double-team social protection. (Fraser 2013a)

Angela McRobbie has recently elaborated on this miscalculation and her role in perpetuating it, especially in seeing consumer feminism as a space of liberation, when that liberation was inherently premised on reproducing young women’s neoliberal subjectivity (McRobbie 2008). On the other hand, she - along with many other Cultural Studies oriented scholars - has also been well attuned to the insidious emergence of precarious, immaterial, largely feminized and unpaid labor that is central to the “creative economy” and the way this affective meaning making creates not only power, but value (McRobbie 2016). In short, well before the emergence of Trump and the wave of other populist movements around the world, critics on the left were attuned to the limits of marketization. But in many cases, most recent leftist critics see something unique about the political economy of immaterial or digital or affective labor, rather than focusing their attention on the larger culture of property that helps that capitalist class siphon surplus value across the system.

By a culture of property I mean a culture whose social relations are ever more deeply commodified; where the ultimate goal is to subject all social interaction (not just those of commerce) to the market system’s understanding of the social process of valorization, geared as it is towards the accumulation of privately held properties; where the primary role of the state is held to be the protection of that process according to the ownership and distribution patterns already existing; where the owners of property are presumed to have created the value protected by the state; where the state protection of this property is held to be natural and/or scientifically necessary thus beyond democratic reorientation; and, finally, where this formal legal environment helps to determine a culture such that individuals respond to the functional discipline of the market as if it were a force of nature rather than a historically contingent social relation.

The staunchest defenders of this reified culture of property rely on what I am terming the cultural efficacy of their own presumptions in order to project this model of society as a universal set of norms with such unquestioned political stability and legitimacy it is unnecessary to have the state. They must assume the legitimacy of, in Marx’s terms, a previous round of primitive accumulation and the direct disciplinary force of the state in preserving the property acquired in that process. They deny the political function of the state and the law in crafting—both historically and presently—a social order and population that more closely resembles the pure model they argue is a natural state of affairs. And, as in Marx’s time, the efficacy of this culture is tied to an ideal subject: homo economicus or what Paul Smith has referred to as “The subject of value” (Smith 2007). This subject, for instance, features centrally in Hayek’s mythical understanding of how the market should operate as a communication mechanism, transmitting prices qua information to buyers and sellers through a non-hierarchical, unplanned, global network helping them make decisions about where to place their investments (Hayek 1945). This rationally calculating, self-organizing subject, is best served by deregulation and re-commodification: regulations are futile attempts at state planning that will never be as efficient at communicating actual supply and demand as the market; but the market can only communicate accurate information if everything - including Polanyi’s fictitious commodities of labor, land, and money along with air, water, health, life, the past, the present, the future - is given a price and sold to the highest bidder. In our present era, this especially includes immaterial, cultural property that is covered by patents, trademarks, and copyrights. The latter, as I’ll elaborate further below, are central to the global capitalist regime of accumulation, facilitating the offshore production, commodity chains, financial arbitrage, and tax havens that make the hegemonic model of globalization possible and profitable.

The xenophobic character of Trump’s populism is indisputable, as it is in the political appeals of Marie Le Pen in France, Nigel Farage and UKIP in the UK and elsewhere. But it is joined with a turn towards autarky and protectionism that is indicative of a politics of the double movement akin to Polanyi’s original concept. The eerie parallels with - and sometimes explicit appeals to - Hitler and the Nazis are most often coded in terms of their white supremacist and anti-semitic appeals. But for Polanyi, the more important feature of the rise of fascism in the 1930s was its centralization of the authority in a leader that promised to provide social protection from the ravages of the market. And here, he finds the rise of a form of authoritarian populism in Russia, Germany, and the United States to be similar in important ways. Polanyi puts it, “the purport of fascism or socialism or new deal is part of the story itself,” but,“The origins of the cataclysm lay in the utopian endeavor of economic liberalism to set up a self-regulating market system” (Polanyi 2001, loc. 1320). In short, like this earlier emergence of the “double movement,” Trump and his cohort are clearly drawing on angst in response to neoliberalism.

The difference is that, just as neoliberalism was a counter response to the the earlier double movement, Trump and company have articulated their politics as a response to what Fraser calls the “triple movement.” In short, because these movements for emancipation were so deeply linked with the kind of “Third Way” neoliberal politics of Clinton, this iteration of the double movement was also what we might call a “counter triple movement:” against the identity politics, egalitarianism, and pleas for tolerance and inclusion that had become prominent features of not only the academic and cultural left, but of neoliberal capitalism itself. And thus while there were massive protests against the travel ban at the end of his first week, Trump’s executives order pulling the U.S. out of the Transpacific Partnership and demand to renegotiate the terms of NAFTA earlier in the week were all but uncontroversial. Right or wrong, these neoliberal policies have long been blamed for the erosion of jobs and livelihoods. And despite the fact that the U.S. Democratic party has long made peace with neoliberalism as the dominant hegemonic ideology, it was the radical right that instantiated the fundamentalist culture of property, often by coding it implicitly to a form of resistance to the progressive movements for liberation.

While Fraser and other critics from the left see this articulation as conjunctural - and the “cultural left” as being responsible for this reaction - I find this periodization somewhat suspect. White supremacy is (and has been) intrinsic to the legitimacy of the U.S. state. As Ira Katznelson discusses in his book Fear Itself, most of the New Deal policies were crafted to win the approval of Southern lawmakers, who refused to allow those policies to equally help both Black and White Americans (CITE). Cowie adds to this the acknowledgement that the U.S. of the 1930s had some of the most restrictive immigration policies of its history, due to the 1924 legislation restricting immigration from anywhere but the (mostly white) countries of Western Europe. In his troubling book, Hitler's American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law, James Q. Wilson notes that the Nazi lawyers attempting to draft their own white supremacist laws looked to U.S. racial codes and this 1924 law (among other legislation). Thus while it is upsetting that the current U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions stated his admiration for that 1924 law in a radio interview with Steve Bannon a few months before the 2016 election, it is less an aberration from U.S. history than a key component of its mainstream. If the New Deal was a “great exception” to the protection of property rights and the rule of capital over labor, then the “triple movement” for the more egalitarian distribution of those protections is the great exception to the white supremacist patriarchy that usually walks hand in hand with these capitalist premises.

Indeed, it would be more accurate to see the economic aspects of counter-double movement of neoliberalism to be of a piece with the political and cultural movements running counter to the triple movement of liberation. Nixon, Reagan, and now Trump are all guilty of playing to these reactionary impulses, but it is more accurate to see them as savvy politicians capitalizing on already existing anxieties than instigators of these more fundamental cultural impulses and political forces. Cultural Studies scholar Jayson Harsin (CITE) notes that the political support for New Deal policies began to evaporate once it became clear that they would help more than just White people. And in her recent controversial history of the origins of the Koch-funded Law and Economics institutions at George Mason University, Nancy MacLean argues that it originates in Virginia first as a way of developing valid, intellectual challenges to desegregation as a form of government coercion and the infringement on private property (CITE). Maclean traces the intellectual origins of this movement to John C. Calhoun who developed the arguments as a senator from South Carolina during the run-up to the Civil War, when there were more millionaires in Mississippi that New York and the value of slaves as capital was greater than that of the railroads. But we could just as easily trace it back to the author of South Carolina’s original colonial charter: John Locke.

MacLean herself traces the Lockean origins of this culture of property (through Calhoun and his appeal to slaveowners in the old south) and she and others highlight about the Law and Economics movement that has helped rearticulate these ideas for the present era. While the stated mission of this interdisciplinary enterprise is simply to bring economics and the law into conversation, the conversation is limited to using what people outside the movement would identify as libertarian, Austrian, classical liberal, or, following Milton Friedman, “neoliberal” understandings of economics. This means seeing the state’s role as limited to the protection of property of all kinds. This movement, like the was inspired by a set of conjunctural circumstances: the transformation of US law and the economy during and after the New Deal. Seeing the New Deal as an affront to the natural laws governing the relationship of state and economy, this insurgent group of lawyers, economists and political scientists set out to reorient the US state towards the principles of classical liberalism.

Nancy Fraser argues that most recent particular articulation of the counter-movement should alert us to the need for a movement that will combine the impulses behind both the social protection from neoliberalism and emancipation from resurgent misogyny, racism, and xenophobia. I agree that the current conjunction - and especially the U.S. context - demands just this approach. However, given the recent emphases of Cultural Studies on issues of emancipation and liberation in terms of these diverse categories of subjectivity, I contend that it is most important to consider the way neoliberalism and the culture of property has impacted the category most of us have in common: that of laborers. As Christopher May says in his critique of the idea of ‘the information society,’

Most of us still need to go to work, where there remains an important division between those who run the company and those who work for it, not least in terms of rewards. When we look at what allows some of us to become rich and the rest of us to get by on our pay and pensions, this still has something to do with who owns what. (Christopher May, 2002)

My critique of intellectual property rights - and of the so-called Free Culture movement of Lessig and others - is premised on an understanding of them as part of a larger neoliberal assault on the rights of citizens and workers and a reorientation of the U.S. state - and through the IMF and World Bank, many other states - to the protection of capitalist profits over the needs of the larger society. Insofar as we now live in a society that claims culture as part of the economy, and in so far as our legal system is increasingly structured by the needs of capitalist property owners first, there is nothing unique about the value produced around intellectual property or the protection of that value by the neoliberal state. The Free Culture movement has identified the renewed visibility of the social production of value, which should inspire a deeper reflection on property rights and neoliberalism more generally. The only way to truly challenge the increased rule and role of IPR, therefore, is to challenge the “propertarian ideology” (Travis) of the neoliberal state. This, in turn, will provide the grounding for precisely the kind of multipronged movement to combat not only the resurgent white-male-supremacy, but the crippling economic policies that have created the inequality, carceral discipline, diseases of despair that are likely to be the scourge of all in the coming years.

0 notes

Text

The Leftwing Has Placed Itself In The Trash Can Of History

http://wp.me/p7IuUt-7Rx

by Paul Craig Roberts, Paulcraigroberts.org: At a time when the Western world desperately needs alternative voices to the neoliberals, the neoconservatives, the presstitutes and the Trump de-regulationists, there are none. The Western leftwing has gone insane. The voices being raised against

SGTreport

0 notes

Text

Today's News 6th February 2017

Today’s News 6th February 2017

Paul Craig Roberts Rages "The Leftwing Has Placed Itself In The Trash Can Of History" Authored by Paul Craig Roberts, At a time when the Western world desperately needs alternative voices to the neoliberals, the neoconservatives, the presstitutes and the Trump de-regulationists, there are none. The Western leftwing has gone insane. The voices being raised against Trump, who does need voices…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Leftwing Has Placed Itself In The Trash Can Of History

The Leftwing Has Placed Itself In The Trash Can Of History

By Dr. Paul Craig Roberts

Paul Craig Roberts.org

February 5, 2017

The Leftwing Has Placed Itself In The Trash Can Of History

At a time when the Western world desperately needs alternative voices to the neoliberals, the neoconservatives, the presstitutes and the Trump de-regulationists, there are none. The Western leftwing has gone insane.

The voices being raised against Trump, who does need…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

nosferanne

replied to your

photo

:

Emira Anand A Regulationist organizer driven off...

She looks amazing! I would flip my lid for a cyberlimb like hers. Loving the costume & character design as a whole, but the details are simply gorgeous. Right down to the lovely melon shade on her nails and the tangibly thick texture on her pants! It really does feel like just a candid shot of her hanging out with a friend snapping a pic.

Doing everything I can not to be all “here’s why you don’t actually like it” because I always wanna throw aside praise. But because I mean to piss off my inner voice, I’m going to admit I was gonna do so and instead say thank you! Especially since my bad color sense often makes me worry about stuff like the nails and stuff. I’m so frustrated that I couldn’t find a good “unpainted nail” color, but that’s for later on.

I’m just so glad you like!

0 notes

Text

Paul Craig Roberts Rages "The Leftwing Has Placed Itself In The Trash Can Of History"

http://wp.me/p7IuUt-7Qs

Authored by Paul Craig Roberts, At a time when the Western world desperately needs alternative voices to the neoliberals, the neoconservatives, the presstitutes and the Trump de-regulationists, there are none. The Western leftwing has gone insane. The voices being raised against Trump, who does

Zero Hedge

0 notes