#shmot

Text

youtube

#ohrwurm#[redacted's] cousin fell this week in Gaza#and ex boyfriend and I are not back together but we spent a long time yesterday reading shmot together#and now I'm listening to this song and crying#תתארו לכם קצת אושר as he says#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

SHMOT

By Agnes

January 11th, 2024

Well, I’m a little late with this week’s drash. I was sort of scattered last week, but still – I spent time with the parsha, Shemot, the beginning of a whole new book — and all I felt was silence. Which is a little wild, right? Since so many iconic moments happen in this first few chapters of Exodus.

We’ve got a new pharaoh who decides to persecute the Israelites, we’ve got midwives saving babies, we’ve got Moses and Pharaoh’s daughter and the burning bush and I-Will-Be-What-I-Will-Be. We’ve got exile and marriage and the people crying out and snake tricks and leprosy tricks and blood tricks and brother Aaron and the launching of an entire political movement.

And it’s not like there was nothing to say. There’s everything to say. There is a Red Sea of commentary and a Jordan River of theology and flowering wadi after flowering wadi of relevant questions about justice and violence and political regimes and belonging. I had some thoughts and I wrote them down but in my heart I felt… silence.

Large portions of my life, including my life now as a writer, revolve around coming up with things to say. I can do that. And sometimes the muscle that comes up with things to say feels like the smallest most marginal muscle in the body.

This morning I got up before sunrise and shoveled snow off my friend’s car. The sky was light by the time I left, all the snow that fell this weekend glowing, and there was a gray mist hanging over the black pavement and the white and brown farmhouses. I drove forty-five minutes down country roads to the nearest train station and rode into New York. It was raining and I had a little time to kill so I stopped into a gallery.

In one room were these beautiful erotic sketches from the fifties, a few paintings and collages. There was a film showing in the back – do you know this film, Fuses, by Carolee Schneeman? It’s a collage of footage shot on 8mm, and she first screened it in 1967. Schneeman is having sex with her partner James, and their cat, Kitch, appears sometimes. There are windows and flashes of light, blurred forms, and moments of clarity. The bodies move and touch and grasp and the camera moves, too, and dances and blurs. The colors are blue and gray and there is no sound.

A few people came in and out of the office in the back but mostly I stood there in my yellow-beige jacket and pink hat, black dripping umbrella in hand, and watched the light move on soft bodies and flicker through tree branches and the cat came in through the window. There is something steely and direct about the film but it is mischievous, too, without being cute. Mostly it is joyful and tender. It is easy and open and just right.

I want my life to involve lots of afternoon sex by an open window. I want to lie in blankets, watch the cat wander the apartment. I want the smell of cooking from the kitchen.

That is what I am thinking as I am watching this film by Carolee Schneeman.

A midrash tells us that many of the Israelites stopped having sex with their partners when the edict came down that boy children would be thrown in the Nile. Husbands and wives separated, because, the midrash says, what was the point? It fell to the women, we learn, to seduce their husbands again.

In the other part of the gallery was a show of newer paintings by an artist I don’t know. Many of them meticulously rendered images of foliage, leaves on top of leaves on top of vines on top of branches. I stopped in front of one painting, maybe three feet tall, two feet wide. I stood close enough that it filled my whole field of vision. In the painting is a dense stand of tall trees. They resemble the trees in the forest I have been walking through every day for the last three months. You can see a tiny sliver of lurid teal sky at the very top of the painting but mostly it is just tree beyond tree beyond tree, and they’re all in bright colors. One tree in the foreground is an electric blue — the blue of irises in spring, the blue of the eyes of a woman I knew once in Lebanon. There are green trees beside it, one the green of fresh olives from the Whole Foods olive bar and one the green of someone’s LL Bean backpack circa 2003. Beyond those trees are trees in golden yellow and deep purply crimson and rich brown like milky black tea and a few in vibrating persimmon orange and salamander red and more blue, but deeper blue, blue like you only see in the sky beyond some saint in a Tintoretto painting.

I stood so close to the painting that I felt the colors overtake my body. It was like they flooded my eyes and had nowhere else to go so they spilled down my back and sloshed up my legs and held me around the waist. And I felt so grateful. I felt so startled and lucky and held.

Then it was time for me to go. And headed north, across Canal Street, I rode an elevator to the seventh floor of an office building and rang the bell on a door next to a realtor’s office and the doctor I’d come to see’s sister opened the door and pointed me to the middle room. And then the doctor came in and asked what was wrong and how long had it been since I’d seen her — a year, right? Maybe two years? I fell in the woods, I said. It was about a month ago. I hurt my leg. I don’t live in New York City anymore but I came down to see her. She said Ahh, okay. Yes, I wondered. Take your pants off, she said, and lie down. I asked how her father was, I remembered he was quite old and she did acupuncture on him every night when she went home. She told me he died last February, and I said I was sorry, and she said yes, it’s very sad. She asked where it was I’d hurt myself and I pointed to a place behind my knee and then she lifted my shirt and pressed on a place on my lower back and I went, Oof! And she went, Right? And I went yes, and as she started to put all these needles in me I felt like I wanted to cry because it is an extraordinary thing when you have been hurting somewhere for a month and you come to someone for help and they teach you about another, perhaps deeper place where you are hurting.

An hour and a half later, after the needles and a good long stretch of her digging her sharp elbow hard into my back and leg, up and down, up and down, and suctioning glass cups all over my lower body that tugged madly on the skin and muscle and left big bruises I was sitting back outside with her sister and eating the raisin pastry she’d given me and drinking the coffee she insisted I sit and sip (are you rushing off somewhere?) and looking at the light green plants under the windows and the deep red Buddha on the altar. I looked around the office and tried to remind myself to drink slowly and asked the doctor when she popped back out from one of the other rooms if it was okay to be doing yoga. And she said maybe, maybe, what kind of yoga, you have to be careful, she said, you need to find a physical therapist when you go back to California. And then the doctor’s husband was there, and he offered me another pastry, and the doctor was joking that he had come for his acupuncture but he was afraid of needles, and it had been a stressful month for him, his blood pressure was a little high.

And I thought about how God says to Moses that Pharaoh will not respond to Moses’s requests, or to the magic tricks he learns with the snake and the leprosy and the blood. Pharaoh will only respond to a greater might, God keeps saying this, Pharaoh will only respond to a greater might, yad chazakah, which literally means a strong arm, and I thought about the doctor’s elbow, and I wondered how many people use their elbows as much as this doctor does on a day to day basis. What a miraculous part of the body, the elbow! And so underappreciated. Maybe God’s strong arm, and greater might, is an elbow.

And I looked at the green plants and the red Buddha and I thought, I want my life to be very simple. I want to work hard and care for things and be around the people I love.

And when I finally left it was still windy and rainy and everything looked gray. And I heard it was snowing upstate, and my friend was wondering whether it would be safe to drive home from the train station, whether I should find another place to stay tonight and I said hm, and I would ask another friend who lives closer by.

Why am I telling you all of this?

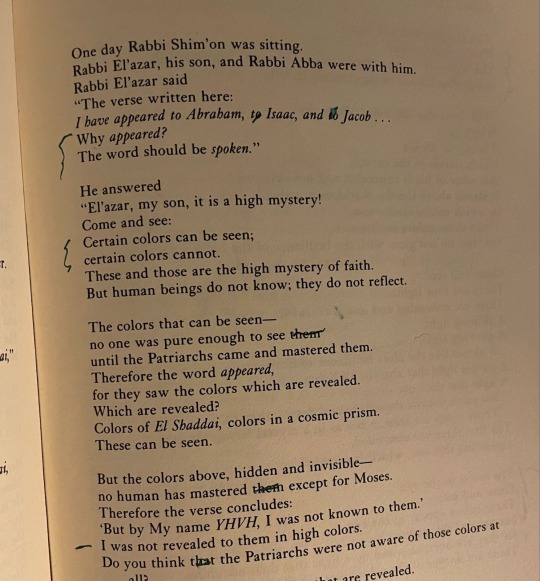

One of the things I read last week when I was trying to find my way out of a silence was a commentary in the Zohar. It’s a commentary on a line that is technically in the next parsha, but I think it’s still relevant.

I’m going to read you a little bit of it, if that’s alright.

And so all week I have been thinking about colors. And what colors might be calling to me out of the parsha. And I didn’t know what to do with that, what to say about it , but I felt like it was important.

But now I think I wasn’t ready to know, and that certain things had to happen first. I had to sit with the silence a while, and feel a little sad, and stressed, and what would I write for the podcast? I had to notice that the little muscle I have trained for years to come up with things to say on command — that this muscle was twitching and maybe a little injured. And then I had to make a wildly inconvenient trip to see a doctor about the injury in my leg. And I had to have time to kill on a rainy day and wander into a gallery and find myself in front of this painting of bright and intricate trees and to feel something like the essence of color completely overtake my body. And remember what it’s like to feel startled by life, and overtaken, and remember that I want to approach Torah from that place, or let Torah approach me. And I had to remember sex by an open window and feel an intense dawning clarity that even though I have been floating for several months now I know, deep down, exactly what I want my life to be. I had to text with my friend about the snow, my friend whose apartment is full of plants and who cares for them so well, I had to find out about where I might stay the night. I had to take a long trip so that a sharp and mighty elbow could press into the parts of me that hurt.

We are starting a new book. It’s a book about becoming a people. It’s a book about how painful and difficult it can be to love a people, specific people, and the divine. It’s a book about rushing and ingratitude and the pains we don’t even notice because we are focused on the wrong injuries.

I wanted to tell you all this as a kind of a prayer. When we hear silence, let us acknowledge the silence. Let us be tender with ourselves, let us be slow. Let us not grasp anxiously after this Torah. Let us let it find us.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What on g*ds green earth did I do to get all of these shmorn shmots????

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Symphony Helio 80

Symphony Helio 80 is a smartphone that has absolutely shifted the official smartphone market of Bangladesh. Upside down, 180º, whatever you may call it, but there is no going back from here. Right here, we are writing history. The phone is priced at BDT 16,999 and there is a good demand for phones around this cost. But it has always been very hard to find something that can completely satisfy someone. Helio 80 by Symphony has proven the market wrong and came as a solid and bold player. It is a full-on all rounder that can satisfy any user. Whether it be a gamer, a hobby mobile photographer, a content watcher, an internet browser, or someone who loves the design. This phone packs it all.

Think about this. A 6.7-inch large Full HD+ AMOLED screen with 120Hz refresh rate, Corning Gorilla Glass 5 front and a glass back. What? Yes, you’ll get it all here. Where is the punchline? There is none. Symphony is giving it all. Ok, the body is not splash resistant and with the 500 nits you may feel a bit low brightness under direct sunlight. It’s not perfect but still not unreasonable for the cost. The rear camera has up to 2K recording and EIS with 1080p recording. It’s never the case that you’ll have stabilization for this price. A big thumbs up to Symphony Mobile. The 108 MP main camera shMots looked great in daylight conditions. The 16 MP selfie camera is also pretty excellent. More information

0 notes

Text

2 Chronicles 4: 1-6. "The Lily Blossom Cup."

The Temple’s Furnishings

Once the Standing Cherubs "Strength and Citizenship" are surpassed, one advances to the Altar:

4 He made a bronze altar twenty cubits long, twenty cubits wide and ten cubits high.[a]

Altars separate our noble and ignoble natures from one another. On one side is man on the other, is God. To sacrifice on the altar is to practice out the side that is at odds with what God has commanded of us in order that we become ceremonially pure.

The Gematria says so long as innocent lives are being lost in the world to satisfy the animal urges of diabolical men, rendering the earth itself a ceremonially impure place, God's face will remain hidden behind the Altar.

To Exchange One Innocent Or Sacrifice Them From Our Midsts For The Sake Of A Guilty Soul Is Not Righteous Virtue But Of The Enemies Of Hashem.

The value In Gematria Is 6492.

2 He made the Sea of cast metal, circular in shape, measuring ten cubits from rim to rim and five cubits[b] high. It took a line of thirty cubits[c] to measure around it.

Within the Temple beyond the Altar, is the next staging arecalled the Mishkan, within this is the Mikvah, or the Basin.

The Mishkan itself was a boxlike structure that measured 30 cubits long and 10 cubits wide (a cubit is the length of the forearm and hand of an adult man). Its walls were made of thick gold-plated acacia wood beams standing side by side to form three sides of a rectangle.

The beams were inserted into interlocking silver sockets and were held in place by long gold-plated wooden poles. A hanging curtain covered the fourth side.

Beams are the faculties, which lock with the eyes, ears, nostrils, etc. and are "held in place" by ones intuition, the golden poles.

The Cast Metal Sea represents the reflective surface in which the Spirit of God saw itself at the dawn of creation. It is a combination of silver and gold, the invisible grace of God, granted to each of us when we are born which should be easily recognized when one looks in the mirror.

A pilgrim enteirng the Second Temple is expected to be learned, kind, and able to see the Grace of God in his reflection, a direct result of the intuition fed his inner being fed by the study of the Tanakh, "the perpetual river of God's Attributes."

Except:

3 Below the rim, figures of bulls encircled it—ten to a cubit.[d] The bulls were cast in two rows in one piece with the Sea.

There are Ten Decrees and this means ten ways for the ego to rebel, unless they are "in one piece with the Sea."

4 The Sea stood on twelve bulls, three facing north, three facing west, three facing south and three facing east. The Sea rested on top of them, and their hindquarters were toward the center. 5 It was a handbreadth[e] in thickness, and its rim was like the rim of a cup, like a lily blossom. It held three thousand baths.[f]

The Twelve Bulls, three to a side, ordinarily represent rebelliousness towards the 12 Noble Skills, UNLESS they have Audienced within the Magen David, the lily blossom at the center of a Jewish Soul which contains the pure water of three thousand baths, the three stages of Jewish evolution, called the Kohanim, Levites, and Israelites.

The Gematria for 1,000 is the same as what is called Bina, or "competence."

Details on the Kohanim can be found in Tzav, details on the Levites appear throughout the Torah, the bulk are found in Shof'tim, and the Israelites are defined in Shmot:

1 These are the names of the sons of Israel who went to Egypt with Jacob, each with his family: 2 Reuben, Simeon, Levi and Judah; 3 Issachar, Zebulun and Benjamin; 4 Dan and Naphtali; Gad and Asher. 5 The descendants of Jacob numbered seventy[a] in all; Joseph was already in Egypt.

Reuben- The Eldest- the Leader

Simeon- Law Abiding

Levi- Experienced

Judah- Praises God

Dan – Intuitive

Naphtali – The Fighter

Gad- Fortunate

Asher- Happy

Issachar- Dedication

Zebulun- Honorable

Joseph- Fruitful

Benjamin- Son of the Right Hand

=the 12 Skills of An Israelite.

6 He then made ten basins for washing and placed five on the south side and five on the north. In them the things to be used for the burnt offerings were rinsed, but the Sea was to be used by the priests for washing.

The Ten Basins are the Decrees, which must be obeyed if one is to demonstrate Jewish Citizenship. Anything sacrificed, time, effort, immmoral desires and acts so the Decrees can be followed rinse the soul in the Sea.

Entering the Temple and moving about the Furnishings is like entering a gym, where one maintains the stamina of one's spiritual muscles. The most important one being the hand that reaches for the cup.

0 notes

Text

In Honor Of Shavuot: Rav Kook On Why The Creator Spoke To Israel

In Honor Of Shavuot: Rav Kook On Why The Creator Spoke To Israel

“Anochi/I Am YHVH Your Elohim Who has taken you out of the narrow land of Egypt, from the house of slavery.” (Shmot 20:2)

Thus begins the most extraordinary moment in world history. The Creator of existence Is Speaking to a group of human beings. YHVH Elokim explains the foundation of existence that must be understood and the…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

13. Parsha Shmot “The Departure.” The Book of Exodus- The Deliverance- Begins.

The Book of Genesis begins with God’s Brilliance, and ends with a hint at mankind’s. Throughout Genesis, we saw men rise and fall, until Abraham, the Founder, rose up and stayed on his feet. From his tutelage grew Isaac, Israel, Joseph and Ephraim, men of distinction. Peace and order followed these men around, one, Joseph saved the world.

Instead of earning greater merits and carrying on the tradition, as humanity is ought and fully capable of, sometimes our enemy, the man of desire, of corruption, is allowed to lead. Then because of delusion about him and his intentions, many die and suffer. Those who watch and wait are as enslaved to him as those experiencing his lash.

It’s just never enough for some or too much for others. The Book of Exodus explains the nature of all slaveries- to those inflicted by self and those by slavers, to the passions, to false gods, to wickedness, laziness, and how different all these are to loyalty to God.

Loyalty to God is the direct result of trust. Doubt in the Will of God is the same as suicide. Doubt in the nature and capacity of the desire to sin is suicide. Liberation starts with the absolution of all doubt. Without Absolution there is no such thing as liberation from sin called “Exodus”.

Exodus is a four part process:

1. We need to realize we are enslaved.

2. All delusion doubt we must be free must be absolved.

3. Effort must be applied to uprooting the causes of the delusion and the shearing away the causes of the slavery.

4. Persons responsible for immoral and unethical acts must be expunged from the world.

What results next is Rule of Law and the establishment of Order.

And here begins the Parsha.

The Israelites Oppressed

1 These are the names of the sons of Israel who went to Egypt with Jacob, each with his family: 2 Reuben, Simeon, Levi and Judah; 3 Issachar, Zebulun and Benjamin; 4 Dan and Naphtali; Gad and Asher. 5 The descendants of Jacob numbered seventy[a] in all; Joseph was already in Egypt.

Reuben- The Eldest- the Leader

Simeon- Law Abiding

Levi- Harmonious

Judah- Praises God

Dan – Intuitive

Naphtali – The Fighter

Gad- Fortunate

Asher- Happy

Issachar- Dedication

Zebulun- Honorable

Joseph- Fruitful

Benjamin- Son of the Right Hand

=the 12 Skills of An Israelite.

You may recall Israel commanded them and his grandsons to procreate with all kinds of desirable attributes and desired outcomes, even paying for them as necessary with time, money, food, and territory.

6 Now Joseph and all his brothers and all that generation died, 7 but the Israelites were exceedingly fruitful; they multiplied greatly, increased in numbers and became so numerous that the land was filled with them.

8 Then a new king, to whom Joseph meant nothing, came to power in Egypt. 9 “Look,” he said to his people, “the Israelites have become far too numerous for us. 10 Come, we must deal shrewdly with them or they will become even more numerous and, if war breaks out, will join our enemies, fight against us and leave the country.”

11 So they put slave masters over them to oppress them with forced labor, and they built Pithom [house of Pitah, "evil engineering"] and Rameses [son of the sun] as store cities for Pharaoh. 12 But the more they were oppressed, the more they multiplied and spread; so the Egyptians came to dread the Israelites 13 and worked them ruthlessly. 14 They made their lives bitter with harsh labor in brick and mortar and with all kinds of work in the fields; in all their harsh labor the Egyptians worked them ruthlessly.

=Egyptians = miserly and miserable people like the Mormons and Evangelicals who worship themselves and each other like little gods, and invest everything in the afterlife while the real world rots.

As soon as the Hebrew Skills die, comes the Miserables and everyone, drop whatever the fuck you're doing and do what they say instead because because because because because...

15 The king of Egypt said to the Hebrew midwives, whose names were Shiphrah and Puah, "Composed, Little Girl." 16 “When you are helping the Hebrew women during childbirth on the delivery stool, if you see that the baby is a boy, kill him; but if it is a girl, let her live.” 17 The midwives, however, feared God and did not do what the king of Egypt had told them to do; they let the boys live. 18 Then the king of Egypt summoned the midwives and asked them, “Why have you done this? Why have you let the boys live?”

19 The midwives answered Pharaoh, “Hebrew women are not like Egyptian women; they are vigorous and give birth before the midwives arrive.”

=Hebrews, those who cross over are not miserable do not need succor to provide the future what it needs.

20 So God was kind to the midwives and the people increased and became even more numerous. 21 And because the midwives feared God, he gave them families of their own.

22 Then Pharaoh gave this order to all his people: “Every Hebrew boy that is born you must throw into the Nile [River of Light], but let every girl live.”

= Every boy must go into the River of Light rather than enter the service of a Confederate. In the Torah, mensch are the animating factor, they represent the qualities, attributes, and character traits of a successful human being. Through a well-ordered process of maturity, they become sentient, and naught but sentient men are fit to Cross Over.

Female forms are the vehicles.

After birth, men (and women) must be baptized in the River of Light, of civilization.

The Birth of Moses

2 Now a man of the tribe of Levi married a Levite woman, 2 and she became pregnant and gave birth to a son. When she saw that he was a fine child, she hid him for three months. 3 But when she could hide him no longer, she got a papyrus basket[b] for him and coated it with tar and pitch. Then she placed the child in it and put it among the reeds along the bank of the Nile. 4 His sister stood at a distance to see what would happen to him.

5 Then Pharaoh’s daughter went down to the Nile to bathe, and her attendants were walking along the riverbank. She saw the basket among the reeds and sent her female slave to get it. 6 She opened it and saw the baby. He was crying, and she felt sorry for him. “This is one of the Hebrew babies,” she said.

7 Then his sister asked Pharaoh’s daughter, “Shall I go and get one of the Hebrew women to nurse the baby for you?”

8 “Yes, go,” she answered. So the girl went and got the baby’s mother. 9 Pharaoh’s daughter said to her, “Take this baby and nurse him for me, and I will pay you.” So the woman took the baby and nursed him. 10 When the child grew older, she took him to Pharaoh’s daughter and he became her son. She named him Moses,[c] saying, “I drew him out of the water.”

The Confederate's Daughter drew Deliverance from Misery out of the River of Light. Said Deliverance was a Lew, the product of Independently unified Levite culture. Lews are the successors of Jews, who are but sojourners.

Moses Flees to Midian, to Judgement

11 One day, after Moses had grown up, he went out to where his own people were and watched them at their hard labor. He saw an Egyptian beating a Hebrew, one of his own people. 12 Looking this way and that and seeing no one, he killed the Egyptian and hid him in the sand. 13 The next day he went out and saw two Hebrews fighting. He asked the one in the wrong, “Why are you hitting your fellow Hebrew?”

=I am now convinced the Egyptians are qualities that cause caviling. During the Escape, every time the Juice start complaining about the trek out of Egypt it is over some yearning to be spoiled and complain rather than work.

Hebrews, the Skills that take one across, out of childhood, away from the gaping maw of history, these and the Egyptians are named throughout the Torah, personified as men, women, fathers, sons, whores, concubines, and places.

For a Hebrew, born of Levites in the River of Light to sucker punch an Egyptian in order to free the sheep by the well this is ideal.

14 The man said, “Who made you ruler and judge over us? Are you thinking of killing me as you killed the Egyptian?” Then Moses was afraid and thought, “What I did must have become known.”

15 When Pharaoh heard of this, he tried to kill Moses, but Moses fled from Pharaoh and went to live in Midian, where he sat down by a well. 16 Now a priest of Midian had seven daughters, and they came to draw water and fill the troughs to water their father’s flock. 17 Some shepherds came along and drove them away, but Moses got up and came to their rescue and watered their flock.

=the Seven Days by the Vault.

18 When the girls returned to Reuel [God shall pasture] their father, he asked them, “Why have you returned so early today?”

19 They answered, “An Egyptian rescued us from the shepherds. He even drew water for us and watered the flock.”

20 “And where is he?” Reuel asked his daughters. “Why did you leave him? Invite him to have something to eat.”

21 Moses agreed to stay with the man, who gave his daughter Zipporah [a goat] to Moses in marriage. 22 Zipporah gave birth to a son, and Moses named him Gershom,[the exile] [d] saying, “I have become a foreigner in a foreign land.”

Yes, when we deliver what is born of the intellect from savagery, the world makes it seem like something strange has happened. 23 During that long period, the king of Egypt died. The Israelites groaned in their slavery and cried out, and their cry for help because of their slavery went up to God. 24 God heard their groaning and he remembered his covenant with Abraham, with Isaac and with Jacob.

25 So God looked on the Israelites and was concerned about them.

The key to understanding the Book of Exodus, the plight of the Israelites and their masters and the outcome is inherent to the reasons they were supposedly enslaved, which the Torah says was jealousy. After that the emphasis was on the propaganda, about a man who was treated like a god and somehow entitled to the entire efforts of a nation to ensure his afterlife in heaven was sumptuous.

We are all prisoners in an Egypt of sorts, slaves to Pro-Lifers that have foregone intelligent responses to their life questions. To leave Egypt is to forego the delusions of self and others like these and just as God did at the end of this section, take a look around and foster some concerns that are long past due.

0 notes

Text

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Passover’s coming..

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last night I was laying in bed, half asleep, and I was thinking a little about names and suddenly one pair just ... felt right. The way I expected it to feel. Like a warm blanket or a second skin. And even though I’d considered those names before they didn’t have the fitting feeling they have today. I don’t know what made the difference, and I might still change my mind before the time comes, but.

I think I know what my new name will be now.

#the road out of egypt is long and weary#names#shmot#november 2019#of course i still havent picked a new last name#but idk what to do about that

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I usually don’t get this much into religion on my blog, but while we’re at it anyway:

The thing about Joseph’s brothers selling him into slavery is that it’s not an isolated incident. It’s part of a much larger pattern of younger brothers gaining supremacy over the older ones, and the older ones retaliating (at times incredibly viciously), which we see over and over throughout the book of Genesis. We see it with literally the first brothers ever to come into existence, Cain and Abel. We see it with Ishmael’s banishment because Sarah wanted the inheritance to be solely Isaac’s (“the son of this slavewoman will not inherit with my son, with Isaac”). We see it with Jacob tricking Esau into selling his birthright and then having to flee the inevitable fallout. We see it with Joseph and his brothers. And then even when Jacob is on his deathbed, we still see him try to bless Joseph’s younger son over the older one. And that’s when Joseph speaks up and says “That is not correct, my father, because this one is the oldest,” and you get a sense of the pattern starting to be broken.

But you don’t really see that pattern break once and for all until the book of Exodus, when Moses is chosen to lead the Hebrews out of Egypt, to basically become the supreme leader above all other leaders in Jewish history... and his older brother, Aaron, is nothing but wholeheartedly loyal and unconditionally supportive of him. There isn’t so much as a flicker of jealousy. He never suggests that maybe this should have been his place instead (even though he’d have a pretty fair case for it, since not only is he the older brother, he’s the one who was living with the other Hebrew slaves while Moses was off living in a palace and then far away in Midian). He goes to find Moses in Midian, embraces and kisses him, and then stands by his side throughout everything that happens afterwards. In light of all the stories of brotherly rivalry we see in the Bible beforehand, that’s incredibly striking.

... Which is one of many reasons why, although I absolutely love The Prince of Egypt, I will never forgive that movie for this:

#I love PoE dearly#like it's easily in my Top 20 movies#but that movie's take on Aaron is... horrendous tbh#anyway#I'll stop rambling about all my Biblical feelings now#torah#bible#tanach#torah analysis#bereishit#shmot

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

TETZAVEH

By Ezra

February 20th, 2024

We are deep in the second book of the Torah, the book called Shmot. That doesn’t mean Exodus. It means “names.”

Why is the book called the book of names? On the surface, it’s a reference to its opening sentence:

וְאֵ֗לֶּה שְׁמוֹת֙ בְּנֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל הַבָּאִ֖ים מִצְרָ֑יְמָה אֵ֣ת יַעֲקֹ֔ב אִ֥ישׁ וּבֵית֖וֹ בָּֽאוּ׃

And these are the names of the children of Israel who came into Egypt, with Yaakov; every man came with his household.

The names listed are the literal children of Israel, the twelve brothers whose names became the names of the tribes of Israel. Every man came with his household. No sisters are listed by name, though there were sisters. Wives, children, no names for them. Just these twelve brothers.

The theme of names hangs over the whole book, but only if you are paying attention. And so does the theme of siblings. Names and siblings are of course ideas that are linked: who gives a name? Usually a parent, a different name for each child.

These twelve brothers had a terrifyingly fraught relationship. Joseph’s brothers nearly killed him. They hated him, partly for the special garment their father had made for Joseph and only Joseph. They tore it off of him, stripped him naked, threw him into a pit and sold him to slave traders. The end result was that they all ended up in Egypt, where their descendents were slaves.

In the second chapter of Shmot, we meet a family that contains three young siblings. In that chapter, we only hear about two of them, and they do not yet have names, nor does their mother. A woman, she is called. A son. His sister. Living in slavery, it’s as if they’ve been dehumanized beyond nameworthiness. And when the nameless mother puts her nameless son in a basket on the river in hopes that he might escape the government child-killers, the nameless sister makes sure that he isn’t harmed.

וַתֵּתַצַּ֥ב אֲחֹת֖וֹ מֵרָחֹ֑ק לְדֵעָ֕ה מַה־יֵּעָשֶׂ֖ה לֽוֹ׃

And his sister stood far off, to know what would be done to him.

Cain kills Abel. Ishmael is driven out of Abraham and Sarah’s home in favor of Isaac. Jacob outwits Eisav and Eisav plots to kill him. Joseph’s brothers sell him to slave traders. But Miriam looks out for her brother. She saves his life.

Miriam, Aaron and Moses grow up to be a trio of siblings working in beautiful cooperation to rescue their people from Egypt and lead a social and spiritual revolution. In the midrash, Moses and Aaron do this dance of humility and mutual encouragement, each ceding leadership to the other. Aaron, the older brother, is not jealous when he finds out Moses has been chosen by God to bring their people out of Egypt. He collaborates with him, he helps him speak to Pharaoh. And then Moses reciprocates that support. Here’s a bit from the Midrash Tanchuma:

Moses said to [Aaron], “The Holy Blessed One has told me to ordain you as high priest.” Aaron said to him, “You have labored on the tabernacle; should I be made high priest?” He said to him, “By your life, even though you are being made high priest, it is as if I were being made [high priest]; for just as you were glad for me in my greatness, so I am glad for you in your greatness.”

-Midrash Tanchuma, Shemini 3

Our parasha consists of commandments given by God to Moses about how his brother Aaron, and Aaron’s sons, are to be dressed while they perform priestly rituals. The clothing is so fabulous, and so meticulously described, it can almost seem like God is rubbing it in Moses’ face. Why, after all, is Moses not the high priest with a dynasty of heirs? Numerous midrashim frame Aaron’s anointment as priest as a punishment for Moses’ initial attempt to refuse God’s call to prophecy. You didn’t want the hard job, now you don’t get the fancy job.

But Moses not only steps aside from the highest position of ritual authority, he himself does every physical preparation for Aaron to occupy that position. Moses lovingly returns the favor of his older brother’s steadfast support up to this point. The tenderness and positivity is almost overwhelming. It’s as if Cain, instead of killing him, had knitted Abel a sweater.

וְעָשִׂ֥יתָ בִגְדֵי־קֹ֖דֶשׁ לְאַהֲרֹ֣ן אָחִ֑יךָ לְכָב֖וֹד וּלְתִפְאָֽרֶת׃

You are to make garments of holiness for Aharon your brother, for glory and for splendor.

-Shmot 28:2

Do not overlook this moment. The exile in Egypt began with a garment torn off in a jealous act of brotherly violence. Now those brothers’ descendents have come out of Egypt, and their leader is asked to create and dress his brother in a beautiful garment, in love and humility, as an indispensable part of their service of God.

Something is being healed in this relationship, something about what siblings can be to one another. The garment Jacob made for Joseph is called a k’tonet passim, often translated as an “ornamented tunic.” And now Moses makes a k’tonet for Aaron to wear. And how is it ornamented?

וְלָ֣קַחְתָּ֔ אֶת־שְׁתֵּ֖י אַבְנֵי־שֹׁ֑הַם וּפִתַּחְתָּ֣ עֲלֵיהֶ֔ם שְׁמ֖וֹת בְּנֵ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃

שִׁשָּׁה֙ מִשְּׁמֹתָ֔ם עַ֖ל הָאֶ֣בֶן הָאֶחָ֑ת וְאֶת־שְׁמ֞וֹת הַשִּׁשָּׁ֧ה הַנּוֹתָרִ֛ים עַל־הָאֶ֥בֶן הַשֵּׁנִ֖ית כְּתוֹלְדֹתָֽם׃

And you shall take two shoham stones, and engrave on them the names of the children of Israel:

six of their names on one stone, and the other six names on the other stone, according to their birth.

-Shmot 28:9-10

Here they are again: shmot b’nei yisrael. The brothers who nearly killed each other, now listed in perfect equality on an ornamented tunic, made by one brother, worn by the other.

It’s all so positive and warm and fuzzy. Brothers, at last, have learned to cooperate.

So here’s the feminist buzzkill: What about sisters? What about Miriam, the oldest sibling among the leaders? What about Dinah, the daughter of Israel, not listed with the sons on the holy breastplate? Where the hell are they?

There are a lot of answers one could give. But in my heart, there are two: one short, one long.

The short answer is easy, it’s baked into all of us who live in a patriarchy built on countless generations of patriarchal norms: they’re women. They’re not there because they never are. They’re supposed to be invisible. They do the dirty work, they cook and clean and they raise the babies. They don’t have their name on a plaque, they don’t serve in public office. Out of sight out of mind.

The long answer does not deny the short answer, which accurately describes the past and present. But the long answer dares to include the future.

When I am most able to believe in the Torah as a divine document is when I can see it as laying out paths for us that we have not yet fully walked. We say in the Torah service every Shabbat, “d’racheiha darchei noam, v’chol netivoteha shalom.” Her ways, the Torah’s ways, are ways of pleasantness, and all of her paths are peace. It can be a hard thing to say when you have just finished reading a portion of a text steeped in ancient habits of misogyny and violence. But the emphasis, in my mind, is on ways, paths. The most transformative ideas in the Torah are the ones that can point us in a direction, that lay out a pathway to be walked in our time and in the future we face.

The progression from Cain and Abel to Miriam, Aaron and Moses, by way of Joseph and his siblings, show us a pathway from violence to cooperation, from scarcity to abundance, from male infighting to feminine leadership. The walking of this pathway is nowhere near finished in the Torah as written. But it has begun. We have moved from a garment violently torn off of a sibling to one lovingly wrapped around a sibling. We have moved from brothers who kill each other to a sister who leads her people in song. We notice that Miriam’s name means, literally, rebellion, and we know that the feminist rebellion of our era is in her name.

Aaron’s breastplate bears shmot bnei yisrael, the names of the children of Israel. Those brothers had a sister named Dinah, whose name is not included. The gap where women have been erased in our Torah feels like an insult, but it can also be an invitation. We can take the loudest silences as opportunities to speak.

The name Dinah means justice, but conjugated in the feminine. In the space where her name should have been, the unwritten future calls to us. In that space, I see visions of priests of all genders with feminine justice emblazoned on our holy garments.

1 note

·

View note

Text

instagram

this girl in my thick cotton coat by dorothyshmot

#shmot#dorothyshmot#coat#fashion design#fashion#fashion designer#designered wear#thick cotton#dress#showroom#fashion showroom

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

I have become increasingly concerned about the assault on free speech taking place throughout the West, particularly in university campuses.[1] This is being done in the name of “safe space,” that is, space in which you are protected against hearing views which might cause you distress, “trigger warnings”[2] and “micro-aggressions,” that is, any remark that someone might find offensive even if no offence is meant.

So far has this gone that at the beginning of the 2017 academic year, students at an Oxford College banned the presence of a representative of the Christian Union on the grounds that some might find their presence alienating and offensive.[3] Increasingly, speakers with controversial views are being disinvited: the number of such incidents on American college campuses rose from 6 in 2000 to 44 in 2016.[4]

Undoubtedly this entire movement was undertaken for the highest of motives, to protect the feelings of the vulnerable. That is a legitimate ethical concern. Jewish law goes to extremes in condemning lashon hara, hurtful or derogatory speech, and the sages were careful to use what they called lashon sagi nahor, euphemism, to avoid language that people might find offensive.

But a safe space is not one in which you silence dissenting views. To the contrary: it is one in which you give a respectful hearing to views opposed to your own, knowing that your views too will be listened to respectfully. That is academic freedom, and it is essential to a free society.[5] As George Orwell said, “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.”

John Stuart Mill likewise wrote that one of the worst offences against freedom is “to stigmatise those who hold the contrary opinion as bad and immoral men.” That is happening today in institutions that are supposed to be the guardians of academic freedom. We are coming perilously close to what Julian Benda called, in 1927, “The treason of the intellectuals,” in which he said that academic life had been degraded to the extent that it had allowed itself to become an arena for “the intellectual organisation of political hatreds.”[6]

What is striking about Judaism, and we see this starkly in this week’s parsha, is that argument and the hearing of contrary views is of the essence of the religious life. Moses argues with God. That is one of the most striking things about him. He argues with Him on their first encounter at the burning bush. Four times he resists God’s call to lead the Israelites to freedom, until God finally gets angry with him (Ex. 3:1–4:7). More significantly, at the end of the parsha he says to God:

“Lord, why have you brought trouble on this people? Why did You send me? Since I came to Pharaoh to speak in Your name, he has brought trouble on this people, and You have not rescued Your people at all.” (Ex. 5:22-23).

This is extraordinary language for a human being to use to God. But Moses was not the first to do so. The first was Abraham, who said, on hearing of God’s plan to destroy the cities of the plain, “Shall the Judge of all the earth not do justice?” (Gen. 18:25).

Similarly, Jeremiah, posing the age-old question of why bad things happen to good people and good things to bad people, asked: “Why does the way of the wicked prosper? Why do all the faithless live at ease?” (Jer. 12:1). In the same vein, Habakkuk challenged God: “Why do You tolerate the treacherous? Why are You silent while the wicked swallow up those more righteous than themselves?” (Hab. 1:13). Job who challenges God’s justice is vindicated in the book that bears his name, while his friends who defended Divine justice are said not to have spoken correctly (Job 42:7-8). Heaven, in short, is not a safe space in the current meaning of the phrase. To the contrary: God loves those who argue with Him – so it seems from Tanakh.

Equally striking is the fact that the sages continued the tradition and gave it a name: argument for the sake of heaven,[7] defined as debate for the sake of truth as opposed to victory.[8] The result is that Judaism is, perhaps uniquely, a civilisation all of whose canonical texts are anthologies of arguments. Midrash operates on the principle that there are “seventy faces” to Torah and thus that every verse is open to multiple interpretations. The Mishnah is full of paragraphs of the form, “Rabbi X says this while Rabbi Y says that.” The Talmud says in the name of God himself, about the conflicting views of the schools of Hillel and Shammai, that “These and those are the words of the living God.”[9]

A standard edition of Mikraot Gedolot consists of the biblical text surrounded by multiple commentaries and even commentaries on the commentaries. The standard edition of the Babylonian Talmud has the text surrounded by the often conflicting views of Rashi and the Tosafists. Moses Maimonides, writing his masterpiece of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah, took the almost unprecedented step of presenting only the halakhic conclusion without the accompanying arguments. The ironic but predictable result was that the Mishneh Torah was eventually surrounded by an endless array of commentaries and arguments. In Judaism there is something holy about argument.

Why so? First, because only God can see the totality of truth. For us, mere mortals who can see only fragments of the truth at any one time, there is an irreducible multiplicity of perspectives. We see reality now one way, now another. The Torah provides us with a dramatic example in its first two chapters, which give us two creation accounts, both true, from different vantage points. The different voices of priest and prophet, Hillel and Shammai, philosopher and mystic, historian and poet, each capture something essential about the spiritual life. Even within a single genre, the sages noted that “No two prophets prophesy in the same style.”[10] Torah is a conversation scored for many voices.

Second, because justice presupposes the principle that in Roman law is called audi alteram partem, “hear the other side.” That is why God wants an Abraham, a Moses, a Jeremiah and a Job to challenge Him, sometimes to plead for mercy or, as in the case of Moses at the end of this week’s parsha, to urge Him to act swiftly in defence of His people.[11] Both the case for the prosecution and the defence must be heard if justice is to be done and seen to be done.

The pursuit of truth and justice require the freedom to disagree. The Netziv argued that it was the prohibition of disagreement that was the sin of the builders of Babel.[12] What we need, therefore, is not “safe spaces” but rather, civility, that is to say, giving a respectful hearing to views with which we disagree. In one of its loveliest passages the Talmud tells us that the views of the school of Hillel became law “because they were pleasant and did not take offence, and because they taught the views of their opponents as well as their own, indeed they taught the views of their opponents before their own.”[13]

And where do we learn this from? From God Himself, who chose as His prophets people who were prepared to argue with Heaven for the sake of Heaven in the name of justice and truth.

When you learn to listen to views different from your own, realising that they are not threatening but enlarging, then you have discovered the life-changing idea of argument for the sake of heaven.

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[image description] distracted boyfriend meme. the girlfriend is labeled “Jon Arnarson’s Heartfelt Lyrics”; the boyfriend is labeled “the fanbase”; the woman in red is labeled “another fucking Drumbot solo” [end image description]

#bandroid#drumbot#jon arnarson#look i know we only really get them in 30 second snippets at most#but bandroid lyrics are actually really lovely????#but drumbot is a robot so we gotta focus on that i guess#plot shmot give me more band content

16 notes

·

View notes