#so its not exclusively serbian beliefs

Text

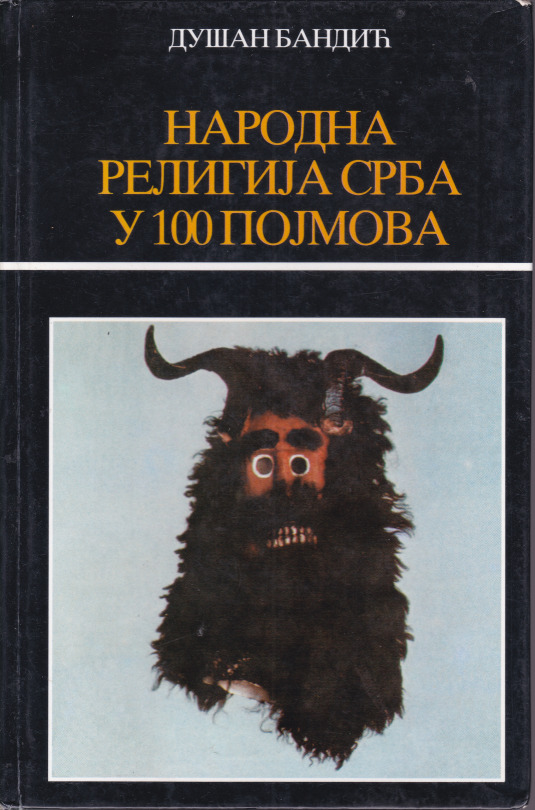

Serbian Folk Religion in 100 Terms // Narodna Religija Srba u 100 Pojmova (1991) - Dušan Bandić

"Dr. Dušan Bandić (1938-2004) was a professor of ethnology at the Faculty of Philosophy in Belgrade and for a time the head of the Department of National Ethnology and Anthropology.''

- in my attempt to make more sources on ex-yu culture accessible, i've begun to scan and share some of the good material i've read! due to some expressed interest, here is a segment on vampires and watermills (which are connected to vampires)!

- for folks who can read serbo-croatian and cyrillic, you can read the direct scans from the book here and for those of you who can't, i've translated the pages into english myself and you can read them here. hope some of you enjoy reading about vampires before they were sexy! if you are interested in reading any of the other segments, you can find a table of contents here and let me know which you'd like to see first.

(note: while im fluent in english and put a lot of effort into these translations, i'm by no means a professional translator. my primary focus was that the facts were translated correctly and relayed what people believed)

#its here finally i did it!!!!#i think i'll start tagging all my archiving and information sharing attempts with#basil archives#really hope somebody enjoys this!#i've read the whole book myself and can confirm that its a lovely source of reliable information#written before the onslaught of nationalism#just a genuine account of some folkloric beliefs#balkan youth have always outlived evil times#myposts#also this books talks about the beliefs of serbs from all over bosnia croatia and motenegro as well#and as we know the beliefs of a village didnt split across ethnic lines before uh modern times#so its not exclusively serbian beliefs#neither of the texts are large btw!#vampires a 5/6 pages watermill like 2 or 3#btw if anyone notices any mistakes please let me know! english or serbian#also if google drive is for whichever reasons not working also let me know!

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Yaga journal: Witches and demons of Eastern Europe

The next article I’ll translate from the issue (I won’t translate all of them since some are not very relevant for this blog) is “Baba Yaga, witches, and the ambiguous demons of oriental Europe” by Stamatis Zochios.

The article opens by praising the 1863′s “Reasoned dictionary of the living russian language”. by scholar, lexicograph and folklorist Vladimir Dahl, which is one of the first “systematic essays” that collects the linguistic treasures of Russia. By collecting more than thirty thousand proverbs and sayings, insisting on the popular and oral language, the Dictionary notably talked about various terms of Russian folklore; domovoi, rusalka, leshii... And when it reaches Baba Yaga, the Dictionary calls her : сказочное страшилищ (skazochnoe strashilishh) , that is to say “monster of fairytales”.But the article wonders about this denomination... Indeed, for many people (such as Bogatyrev) Baba Yaga, like other characters of Russian fairytales (Kochtcheï or Zmey Gorynych) do not exist in popular demonology, and is thus exclusively a character of fairy tales, in which she fulfills very specific functions (aggressor, donator if we take back Propp’s system). But the author of this article wonder if Baba Yaga can’t actually be found in “other folkloric genres” - maybe she is present in legends, in popular beliefs, in superstitions and incantations.

Baba Yaga, as depicted in the roleplaying game “Vampire: The Masquerade”

For example, in a 19th century book by Piotr Efimenko called “Material for ethnography of the Russian population of the Arkhangelsk province”, there is an incantation recorded about a man who wante to seduce/make a woman fall in love with him. During this incantation the man invokes the “demons that served Herod”, Sava, Koldun and Asaul and then - the incantation continues by talking about “three times nine girls” under an oak tree”, to which Baba Yaga brings light. The ritual is about burning wood with the light brought by Baba Yaga, so that the girl may “burn with love” in return. Efimenko also mentions another “old spell for love” that goes like this: “In the middle of the field there are 77 pans of red copper, and on each of them there are 77 Egi-Babas. Each 77 Egi-Babas have 77 daughters with each 77 staffs and 77 brooms. Me, servant of God (insert the man’s name here) beg the daughters of the Egi-Babas. I salute you, daughters of Egi-Babas, and make the servant of God (insert name of the girl here) fall inlove, and bring her to the servant of God (insert name of the man here).” The fact Baba Yaga appears in magical incantations proves that she doesn’t exist merely in fairytales, but was also part of the folk-religion alongside the leshii, rusalka, kikimora and domovoi. However two details have to be insisted upon.

One: the variation of the name Baba Yaga, as the plural “Egi-Babas”. The name Baba Yaga appears in numerous different languages. In Russian and Ukrainian we find Баба-Язя, Язя, Язі-баба, Гадра ; in Polish jędza, babojędza ; in Czech jezinka, Ježibaba meaning “witch, woman of the forest”, in Serbian баба jега ; in Slovanian jaga baba, ježi baba ... Baba is not a problem in itself. Baba, comes from the old Slavic баба and is a diminutive of бабушка (babyshka), “grand-mother” - which means all at the same time a “peasant woman”, “a midwife”, a (school mistress? the article is a bit unclear here), a “stone statue of a pagan deity”, and in general a woman, young or old. Of course, while the alternate meanings cannot be ignored, the main meaning for Baba Yaga’s name is “old woman”. Then comes “Yaga” and its variations, “Egi”, “Jedzi”, “Jedza”, which is more problematic. In Fasmer’s etymology dictionary, he thinks it comes from the proto-Slagic (j)ega, meaning “wrath” or “horror”. Most dictionaries take back this etymology, and consider it a mix of the term baba, старуха (staruha), “old woman”, and of яга, злая (zlaia), “evil, pain, torment, problem”. So it would mean злая женщина (zlaja zhenshhina), “the woman of evil”, “the tormenting woman”. However this interpretation of Yaga as “pain” is deemed restrictive by the author of this article.

Aleksandr Afanassiev, in his “Poetic concepts of the Slavs on nature”, proposed a different etymology coming from the anskrit “ahi”, meaning “snake”. Thus, Baba Yaga would be originally a snake-woman similar to the lamia and drangua of the Neo-hellenistic fairytales and Albanian beliefs. Slavic folklore seems to push towards this direction since sometimes Baba Yaga is the mother of three demon-like daughters (who sometimes can be princesses, with one marrying the hero), and of a son-snake that will be killed by the hero. Slovakian fairytales tale back the link with snakes, as they call the sons of Jezi-Baba “demon snakes”. On top of that, an incantation from the 18th century to banish snakes talks about Yaga Zmeia Bura (Yaga the brown snake): “I will send Yaga the brown snake after you. Yaga the brown snake will cover your wound with wool.” According to Polivka, “jaza” is a countryside term to talk about a mythical snake that humans never see, and that turns every seven years into a winged seven-headed serpent. With all that being said, it becomes clear (at least to the author of this article) that one of the versions of Yaga is the drakaina, the female dragon with human characteristics. These entities are usually depicted with the head and torso of women, but the lower body of a snake. They are a big feature of the mythologies of the Eurasian lands - in France the most famous example is Mélusine, the half-snake half-woman queen, whose story was recorded between the end of the 14th century and the beginning of the 15th by Jean d’Arras (in his prose novel La Noble Histoire de Lusignan) and by Couldrette (in the poetic work Roman de Mélusine). For some scholars, these hybrid womans are derived from the Mother Goddess figure, and by their physical duality manifest their double nature of benevolence-malevolence, aggressor-donator.

If we come back to the incantation of Efimenko, we notice that the 77 daughters of Baba Yaga each have a “metly”, a “broom”. This object isn’t just the broom Baba Yaga uses alongside her mortar and pestle to travel around - it is also the main attribute of the witches, and the witch with her broom is a motif prevalent in numerous textes of Western Europe between the 15th and 16th centuries. Already in medieval literature examples of this topic could be found: in the French works “Perceforest” and “Champion des dames”, the old witches are described flyng on staffs or brooms, turning into birds, to either eat little children or go to witches’ sabbaths. Baba Yaga travels similarly: Afanassiev noted that she goes to gathering of witches while riding a mortar, with a pestle in one hand and a broom in the other. Federowsky noted that Baba Yaga was supposed to be either the “aunt” or the “mistress” of all witches. Baba Yaga herself in often called an old witch, numerous dictionaries explaining her name as meaning старуха-колдунья (staruha-koldun’ja), which literaly means old witch. Even more precisely, she is an old witch who kidnaps children in order to devour their flesh and drink their blood. We find back in other countries of Europe this myth of the “bogeywoman cannibal-witch”, especially dangerous towards newborns and mothers, as the “strix” or “strige”. According to Polivka, in his 1922 article about the supernatural in Slovakian fairytales, the ježibaba is the same being as the striga/strige. And he also ties these two beings to the bosorka, a creature found in Slovakia, in eastern Moravia, and in Wallachia, and which means originally a witch or a sorceress, but that in folklore took a role similar to the striga or ježibaba.

Vinogradova, in a study of the figure of the bosorka, described this Carpathian-Ukrainian witch as a being that attacked people in different ways. For example she stole the milk from the cows - a recurring theme of witches tales in Western Europe (mentionned by Luther in his texts as to one of the reasons witches had to be put to death), but that also corresponds to a tale of the Baba Yaga where she is depicted as sucking the milk out of the breast of a young woman (an AT 519 tale, “The Strong Woman as Bride”). In conclusion, the striga-bosorka is clearly related to the Slovakian version of Baba Yaga, the Ježibaba. The Ježibaba, a figure of Western Slavic folklore, also appears as numerous local variations. She is Jenzibaba, Jendzibaba, Endzibaba, Jazibaba, and in Poland she is either “jedza-baba” (the very wicked woman) or “jedzona, jedza-baba, jagababa” (witch). However this Slovakian witch isn’t always evil: in three fairytales, Ježibaba is a helper bringing gifts, appearing as a trio of sisters (with a clear nod to the three fatae, the three moirae or the three fairies of traditional fairytales) who help the hero escape an ogre who hunts him. They help him by gifting him with food, and then lending him their magical dogs. And in other farytale, the three sisters help a lazy girl spin threads.

In this last case, Ježibaba is tied to the action of spinning. It isn’t a surprise as Baba Yaga herself is often depicted spinning wool or owning a loom ; and several times she asks the young girls who arrive at her home to spin for her (AT 480, The Spinning-Woman by the Spring) - AND in some variations, her isba doesn’t stand on chicken legs, but rather on a spindle. This relationship between the female supernatural figure (fairy or witch) and the action of spinning is very typical of European folkore. In several Eastern Slavic traditions, the figure of Paraskeva-Piatnitsa (or Pyatnitsa-Prascovia, who is often related to Baba Yaga), is an important saint, personification of Friday and protectress of crops - and she punishes women who dare spin on the fifth day of the week. Sometimes it is a strong punishment: she will deform the fingers of the woman who dares spin the friday, which relates her to the naroua (or naroue, narova, narove) a nocturnal fairy of Isère and Savoie in France, who manifests during the Twelve Days of Christmas and enters home to punish those that work at midnight or during holidays - especially spinners and lacemakers. In a Savoie folktales she is said to beat up lacemakers until almost killing them, hits them on the fingers with her wand, beats them up with a beef’s leg or a beef’s nerves, and attacks children with both a cow’s leg in one hand and a beef’s leg in another. These bans are also found in the Greek version of Piatnitsa: Agia Paraskevi, Saint Paraskevi, who punishes the spinners that work on Thursday’s nights, during Friday, or during the feast-day of the Saint (26 of July). But her punishment is to force them to eat the flesh of a corpse. Finally, we find the link between spinning and the demonic woman/witch/fairy through the Romanian cousin of Baba Yaga - Baba Cloanta, who says that she is ugly because she spinned too much during her life. And it all ties back to the “Perceforest” tale mentionned above - in the text, the witches, described as old matrons disheveled and bearded, not only fly around on staffs and little wooden chairs, but also by riding on spindles and reels/spools.

Another typical example of “demonic woman” often compared and related to Baba Yaga is the character known as “Perchta” in her Alpine-Germanic form, Baba Pehtra in Slovenia, or Pechtrababajaga according to a Russian neologism. The name Perchta, Berchta, Percht, Bercht comes from the old high German “beraht”, of the Old German “behrt” and of the root “berhto-”, which is tied to the French “brillant” and the English “brilliant”. So Berchta, or Perchta, would mean “the brilliant one”, “the bringer of light”. Why such a positive name for a malevolent character?

In 1468, the Thesaurus pauperum, written by John XXI, compares two fairies with a cult in medieval France, “Satia” and “dame Abonde”, with another mythological woman: Perchta. The Thesaurus pauperum describes “another type of superstition and idolatry” which consists in leaving at night recipients with food and drinks, destined to ladies that are supposed to visit the house - dame Abonde or Satia, that is also known as “dame Percht” or “Perchtum”, who comes with her whole “troop”. In exchange of finding these open recipients, the ladies will thenfill them regularly, bringing with them riches and abundance. “Many believed that it is during the holy nights, between the birth of Jesus and the night of the Epiphany, that these ladies, led by Perchta, visit homes”, and thus during these nights, people leave on the table bread, chesse, milk, meat, eggs, wine and water, alongside spoons, plates, cups, knives, so that when lady Perchta and her group visit the house, they find everything prepared for them, and bless the house in return with prosperity. So the text cannot be more explict: peasants prepared meals at night for the visit of lady Perchta, it is the custom of the “mensas ornare”, to prepare the table in honor of a lady visiting houses at night. If she finds offerings - cuttlery, drinks, food, especially sugary food - she rewards the house with riches. Else, she punishes the inhabitants of the home.

But Perchta doesn’t just punish for this missing meal. Several stories also describe Perchta looking everywhere in the house she visits, checking every corner to spot any “irregularity”. The most serious of those sins is tied to spinning: the woman of the house is forced to stop her work before midnight, or to not work on a holiday - especially an important holiday of the Twelve Days, such as Christmas or the Epiphany. If the woman is spotted working ; or if Perchta doesn’t found the house cleaned up and tidied up ; or if the flax is not spinned, the goddess (Perchta) will punish the woman. This is why she was called “Spinnstubenfrau”, “the woman of the spinning room”. It is also a nickname of a German spirit known as Berchta - as Spinnstubenfrau, she takes the shape of an old witch who appears in people’s houses during the winter months. She is the guardian spirit of barns and of the spinning-room, who always check work is properly and correctly done. And her punishment was quite brutal: she split open the belly of her victim, and replaces the entrails with garbage. Thomas Hill in his article “Perchta the Belly Slitther” sees in this punishment the remnants of old chamanic-initiation rite ; which would tie to it an analysis done by Andrey Toporkov concerning the “cooking of the child” by Baba Yaga in the storyes of the type AT 327 C or F. In these tales a boy (it might be Ivashka, Zhikharko, Filyushka...) arrives at Baba Yag’s isba, and the witch asks her daughter to cook the boy. The boy makes sure he can’t be pushed in the oven by taking a wrong body posture, and convinces the girl to show him how he should enter the oven. Baba Yaga shows him to do so, enters the oven, and the boy finds the door behind her, trapping Baba Yaga in the fire. According to Toporkov, we can find behind this story an old ritual according to which a baby was placed three times in an oven to give it strength. (The article reminds that Vladimir Propp did highlight the function of Baba Yaga as an “initiation rite” in fairytales - and how Propp considered that Baba Yaga is a caricature of the leader of the rite of passage in primitive societies). And finally, in a tale of Yakutia, the Ega-Baba is described as a chaman, invoked to resurrect a killed person. The author of the article concludes that the first link between Yaga and Perchta is that they are witches/goddesses that can be protectress, but have a demonic/punishment-aspect that can be balanced by a benevolent/initiation-aspect. But it doesn’t stop here.

The Twelve Days are celebrations in honor of Perchta, practiced in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Still today, “Percht” is a term used to call masked person who haunt at night the villages of High-Styria or the land of Salzbourg: they visit houses while wearing masks, clothed in tatters and holding brooms. During these celebrations, young people either dress up as beautiful girls in traditional costumes (the schöne Perchten), either as ugly old woman (die schiache Perchten). These last ones are inspired by the numerous depictions of Perchta as an old woman, or sometimes a human-animal hybrid, with revolting trait - most prominent of them being the feet of a goose. This could explain in Serbia the existence of a Baba Jaga/Baba Jega with a chicken feet, or even the chicken feet carrying the isba of Baba Yaga. This deformation also recalls a figure of the French region of Franche-Comté, Tante Arie (Aunt Arie), another supernatural woman of the Twelve Days tied to spinning. The second most prominent trait of the “old Perchta” is an iron nose - already in the 14th century, Martin of Amberg wrote about “Percht mit der eisnen nasen”, “Percht with an iron nose”. Yaga also sometimes hag an iron nose, and this is why she was associated with other figures of Carpathian or Western Ukraine folklores - such as Zalizna baba or Zaliznonosa baba, the “old woman of iron”, who lives in a palace standing on duck legs ; there is also Vasorru Baba, the iron-nosed woman of Hungaria. Or Huld - another Spinsstubenfrau, often related to Perchta, but who has more sinister connotations. Huld has an enormous nose according to Luther, and Grimm notes that sometimes she appears as a witch with one very long tooth. This last characteristic if also recurring in Eastern Europe’s mythologies: in Serbia Gvozdenzuba (Iron Teeth) is said to burn the bad spinners ; and Baba Yaga is sometimes described with one or several long teeth, often in iron. But it is another aspect of the myths of Huld, also known as Holda or Frau Holle, that led the scholar Potebnja to relate her to Perchta and Baba Yaga.

According to German folk-belief, Huld (or often Perchta) shakes her pillowcases filled with feathers, which causes the snow or the frost ; and thunder rumbles when she moves her linen spool. It is also said that the Milky Way was spinned with her spinning wheel - and thus she controls the weather. In a very similar function, the Baba Jaudocha of Western Ukraine (also called Baba Dochia, Odochia, Eudochia, Dochita, Baba Odotia, a name coming from the Greek Eudokia) is often associated with Baba Yaga, and she also creates snow by moving either her twelve pillows, or her fur coat. According to Afanassiev, the Bielorussians believed that behind the thunderclouds, you could find Baba Yaga with her broom, her mortar, her magic carpet, her flying horses or her seven-league boots. For the Slovakians, Yaga could create bad or beautiful weather. In Russia, she is sometimes called ярою, бурою, дикою , “jaroju, buroju, dikoju”, a name connected to thunderstorms. Sometimes Yaga and her daughters appear as flying snakes - and the полет змея, the “polet smeja”, the “flight of the snake” was believed to cause storms, thunder and earthquakes. In a popular folk-song, Yaga is called the witch of winter: “Sun, you saw the old Yaga, Baba Yaga, the winter witch, this ferocious woman, she escaped spring, she fled away from the just, she brought cold in a bag, she shook cold on earth, she tripped and rolled down the hill.” Finally, for Potebnia, the duality and ambiguity of Baba Yaga, who steals away and yet gives, can be related to the duality of the cloud, who fertilizes the land in summer, and brings rain in winter. Baba Yaga is a solar goddess as much as a chthonian goddess - she conjointly protects births, and yet is a psychopomp causing death.

It seems, through these examples, that Baba Yaga is a goddess - or to be precise, a spirit of nature. Sometimes she is a leshachikha, the wife of the “leshii”, the spirit of the forest, and she herself is a spirit of the woods, living alone in an isolated isba deep in the thick forests. She is thus often paralleled with Muma Padurii, the Mother of the Forest of Romanian folklore, who lives in a hut above rooster’s legs, surrounded by a fence covered in skulls, and who steals children away (in tales of the type AT 327 A, Hansel and Gretel). This aspect of Baba Yaga as a spirit of the forest, and more generally as a “genius loci” (spirit of the place) also makes her similar to another very important figure of Slavic folklore: Полудница (Poludnica), the “woman of noon”. She is an old woman with long thick hair, wearing rags, and who lives in reeds and nettles ; or she can rather be a very beautiful maiden dressed in white, who punishes those that work at noon. She especially appears in rye fields, and protects the harvest. In other tales, she rather sucks away the life-force of the fields - which would relate her to some stories where Baba Yaga runs through rye fields (either with a scarf of her head, or with her hair flowing behind her). Poludnica can also look like Baya Yaga: Roger Caillois, in his article “Spectres de midi dans la démonologie slave” (Noon wraiths in the Slavic demonology), mentionned that Poludnica was a liminal deity of fields, to which one chanted полудница во ржи, покажи рубежи, куда хошь побѣжи !, “Poludnicaa in the rye - show the limits - and go where you want.” This liminal aspects reminds of an aspect of Baba Yaga as a genius loci, tied to a specific place that she defends. It is an aspect found as Baba Yaga, Baba Gorbata, Polydnitsa and Pozhinalka: Baba Yaga is either a benevolent spirit that protects the place and the harvest ; either she is a malevolent sprit that absorbs the life-force of the harvest and destroys it. This is why she must be chased away, and thus it explains a Slovanian song that people sing during the holiday of Jurij (the feast day of Saint George), the 23rd of April, an agrarian holiday for the resurrection of nature: Zelenga Jurja (Green George), we guide, butter and eggs we ask, the Baba Yaga we banish, the Spring we spread!”. This chant was tied with a ritual sacrifice: the mannequin of an old woman had to be burned. As such, Baba Yaga and her avatars, was a spirt that had to be hunted down or banned - which is a custom found all over Europe, but especially in Slavic Europe. At the end of the harvest, several magical formulas were used to push away or cut into pieces the “old woman” ; and we can think back of Frazer’s work on the figure of the “Hag” (which in the English languages means as much an old woman as a malevolent spirit), who is herself a dual figure. In a village of Styria, the Mother of wheat, is said to be dressed in white and to be born from the last wheat bundle. She can be seen at midnight in wheat fields, that she crosses to fertilize ; but if she is angry against a farmer, she will dry up all of his wheat. But then the old woman must be sacrificed - just like in the feast of Jurij.

The author concludes that the “folkloric” aspect of Baba Yaga stays relatively unknown in the Western world and the non-russophone lands. The most detailed and complete work the author could find about it is Andreas Johns’ book “Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale”. The author of the article tried to prove that, as Johns said, the Baba Yaga is fundamentaly ambiguous - at the same time a kidnaping witch, a psychopomp, a cannibal, a protectress of birth, a guardian of places, a spirit of nature and harvests... And that she is part of an entire web and system of demon-feminine figures that create a mythology ensemble with common characteristic - very present in Eastern Europe, but still existing on the continent as a whole.

#the yaga journal#baba yaga#slavic folklore#eastern europe folklore#european folklore#perchta#fairies#fairy folklore#demonology#demons#witches

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

The emerging new world order’s alarm bells: Men like Brandon Tarrant and Andreas Breivik

By James M. Dorsey

A podcast version of this story is available on Soundcloud, Itunes, Spotify, Stitcher, TuneIn and Tumblr

This week’s attack on two mosques in New Zealand reflects a paradigm shift: the erosion of liberal values and the rise of civilisationalism at the expense of the nation state.

So do broader phenomena like wide spread Islamophobia with the crackdown on Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang as its extreme, and growing ant-Semitism These phenomena are fuelled by increasing intolerance and racism enabled by far right and world leaders as well as ultra-conservatives and jihadists.

These world leaders and far right ideologues couch their policies and views in terms of defending a civilization rather than exclusively a nation state defined by its citizenry and borders.

As a result, men like China’s Xi Jingping, India’s Narendra Modi, Hungary’s Victor Orban and US president Donald J. Trump as well as ideologues such as Steve Bannon, Mr. Trump’s former strategy advisor, shape an environment that legitimizes violence against the other.

By further enabling abuse of human, minority and refugee rights, they facilitate the erosion of the norms of debate and mainstream hate speech.

Blunt and crude language employed by leaders, politicians, some media and some people of the cloth helps shape an environment in which concepts of civility and mutual respect are lost.

Consequently, the likes of Brenton Tarrant, the perpetrator of the attacks on the Christchurch mosque in which 49 people died, or Andreas Breivik, the Norwegian far-right militant who in 2011 killed 78 people in attacks on government buildings and a youth summer camp, are not simply products of prejudice.

Prejudice, often only latent, is a fact of life. Its inculcated in whatever culture as well as education in schools and homes irrespective of political, religious, liberal, conservative and societal environment.

Men like Messrs. Tarrant and Breivik emerge when prejudice is weaponized by a political and/or social environment that legitimizes it. They are emboldened when prejudice fuses with politically and/or religiously manufactured fear, the undermining of principles of relativity, increased currency of absolutism, and the hollowing out of pluralism.

Their world is powered by the progressive abandonment of the notion of a world that is populated by a multitude of equally valid faiths, worldviews and belief systems.

The rise of civilisationalism allows men like Messrs. Tarrant and Breivik, white Christian supremacists, to justify their acts of violence in civilizational terms. They believe their civilization is under attack as a result of pluralism, diversity and migration

The same is true for jihadists who aim to brutally establish their vision of Islamic rule at the expense not only of non-Muslim minorities but also Muslims they deem no different than infidels.

Civilisationalism provides the justification for men like Hungary’s Mr. Orban to adopt militant anti-migration policies and launch attacks laced with anti-Semitism on liberals like financier and philanthropist George Soros.

It also fuels China’s crackdown on Turkic Muslims in the north-western province of Xinjiang, an attempt to Sinicize Islam and the most frontal assault on the Islamic faith in recent memory.

Similarly, civilisationalism validates Mr. Modi’s notions of India as a Hindu civilizational state and Mr. Trump’s anti-Muslim and anti-migrant policies and his continued vacillation between lending racism and white supremacism legitimacy and condemning far-right exclusivism.

Civilisationalism poses a threat not only to the world we live in today but to the outcome of the geopolitical struggle of what will be the new world order. The threat goes beyond the battle for spheres of influence or competition of political systems.

Civilisationalism creates the glue for like-minded thinking, if not a tacit understanding, between men like Messrs. Xi, Orban, Modi and Trump, on the values that should undergird a new world order.

These men couch their policies as much in civilisationalism as in terms of defense of national interest and security.

Their embrace of civilisationalism benefits from the fact that 21st century autocracy and authoritarianism vests survival not only in repression of dissent and denial of freedom of expression but also maintaining at least some of the trappings of pluralism.

Those trappings can include representational bodies with no or severely limited powers, toothless opposition groups, government-controlled non-governmental organizations, and some degree of accountability.

The rise of civilisationalism is further facilitated by a failure to realize that the crisis of democracy and the revival of authoritarianism did not emerge recently but dates back to the first half of 1990s.

Political scientists Anna Lührmann and Staffan I. Lindberg concluded in a just published study that some 75 countries have embraced elements of autocracy since the mid-1990s. Key countries among them have also adopted aspects of civilisationalism.

The scholars, nonetheless, strucl an optimistic tone. “While this is a cause for concern, the historical perspective…shows that panic is not warranted: the current declines are relatively mild and the global share of democratic countries remains close to its all-time high,” they said.

This week’s attack in Christchurch is one of multiple civilizational writings on the wall.

So are the killings committed by Mr. Breivik; multiple jihadist attacks, the recasting of political strife in Syria and Bahrain in sectarian terms; the increasing precarity of minorities whether Muslim, Christian or Jewish; rising Buddhist nationalism, and the lack of humanitarianism and compassion towards refugees fleeing war and persecution.

These alarm bells coupled with the tacit civilisationalism-based understanding between some of the world’s most powerful men brushes aside the lessons of genocide in recent decades.

Ignoring the lessons of Nazi Germany, Hutu Rwanda, the Serbian siege of Srebrenica or the Islamic State’s Yazidis poses the foremost threat to a world that is based on principles of humanitarianism, compassion, live-and-let-live, and human and minority rights.

Framing the challenge, Financial Times columnist Gideon Rahman noted that Mr. Trump’s “predecessors confidently proclaimed that American values were ‘universal’ and were destined to triumph across the world. And it was the global power of western ideas that has made the nation-state the international norm for political organisation. The rise of Asian powers such as China and India may create new models: step forward, the ‘civilisation state.’”

Mr. Rahman argues that a civilizational state rejects human rights, propagates exclusivism and institutions that are rooted in a unique culture rather than principles of equality and universalism, and distrusts minorities and migrants because they are not part of a core civilisation.

In short, a breeding ground for strife and conflict that can only be kept in check by increasingly harsh repression and/or attempts at mass re-education and homogenization of the other – ultimately a recipe for instability rather than stability and equitable progress.

Dr. James M. Dorsey is a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, co-director of the University of Würzburg’s Institute for Fan Culture, and co-host of the New Books in Middle Eastern Studies podcast. James is the author of The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer blog, a book with the same title and a co-authored volume, Comparative Political Transitions between Southeast Asia and the Middle East and North Africa as well as Shifting Sands, Essays on Sports and Politics in the Middle East and North Africa and recently published China and the Middle East: Venturing into the Maelstrom

#China (PRC)#china#india#United States#hungary#xi jinping#narendra modi#modi#orban#victor orban#Religion#civilization#islam#new world order#democracy#autocracy#xinjiang

0 notes

Text

Libertarian Humanism or Critical Utopianism? The Demise of the Revolutionary Communist Party

Dave Walker, New Interventions, Vol.8 No.3, 1998

WELL, it’s now official. The Revolutionary Communist Party is no more. According to the editorial in the March 1998 issue of LM (née Living Marxism), the RCP has been wound up. The reason is simple. What Marx wrote ‘is in many ways less pertinent now than at any time in the past century and a half’. Marxism is all about revolution, ‘and of what relevance is that’, we are asked, when ‘the working-class movement has been consigned to the heritage museums and the only people likely to be storming palaces are tour parties of sad little pilgrims worshipping the ground that Princess Diana walked on’.

We had been warned. Towards the end of last year, Channel Four outraged the fragile sensitivities of the Green movement with its series Against Nature, three programmes which challenged many of the fundamental tenets of Greenery, such as population growth, industrialisation, global warming and animal experimentation. Green spokesman George Monbiot went ballistic, accusing the series of being a conspiracy organised by the RCP because it featured Frank Füredi, the party’s founder and chief theoretician (Guardian, 18 December 1997). Things became interesting with Füredi’s reply in the next day’s issue. He carefully steered around his long-running central involvement with the RCP, saying that he had not been interested in party politics for the last seven years, that his last four books couldn’t be considered as Marxist, and that he considered himself a ‘libertarian humanist’. The day after that, the paper reported Martin Durkin, the Against Nature producer, saying that the RCP had been dissolved a year previously. Not known as an RCP member or supporter, it’s not clear how he was privy to such information.

Another pointer was when ITN, in its libel case against LM over what the journal considered was misleading reportage on the war in former Yugoslavia, charged it with having the ‘improper motive’ of ‘fuelling its campaign of pro-Serbian propaganda ... thereby hoping to further the cause of revolutionary communism and/or Marxist ideology’. This, said LM’s Helen Searls in the November 1997 issue, was a ‘caricature’ of the magazine’s politics, and it was not clear what annoyed her the more: that ITN was misrepresenting LM’s formally neutralist stand on the Yugoslav wars, or that LM was being associated with ‘the cause of revolutionary communism and/or Marxist ideology’.

Observers of the left-wing scene had noticed that over the last few years, the RCP, which ever since its formation in 1981 had always enjoyed a high public profile, was engaged in what can only be described as a steady drift away from any recognisable political engagement, which has ultimately led to the virtual abandonment of any concept of recognisable politics altogether. For the past year, the monthly Living Marxism has been marketed under the anonymous and meaningless title of LM, and is almost exclusively concerned with heaving brickbats at the liberal media, censorship, the intrusion of the state into people’s lives, and its latest theoretical discovery, the ‘culture of low expectations’. The occasional pieces on more obviously political issues serve as incongruous reminders of a barely-remembered past amongst the increasingly repetitive and narrowly-focused material that fills the magazine these days.

Up until the March 1998 issue, there had not been any open renunciation of Marxism, but that the initialisation of the magazine’s title was not an accident or a mere question of style was borne out by an article by Füredi in the LM for May 1997:

‘In today’s circumstances class politics cannot be reinvented, rebuilt, reinvigorated or rescued. Why? Because any dynamic political outlook needs to exist in an interaction with existing individual consciousness. And contemporary forms of consciousness in our atomised societies cannot be used as the foundation for a more developed politics of solidarity.’

What has happened is that we have been hit with ‘the decline of subjectivity’; ‘humanity has effectively been recast in the role of object to which things happen that are beyond all control’. So what can we do? Well, not much, it seems. Such concepts as class struggle or socialism ‘are abstractions that remain external to an environment where the very belief in the human potential faces scorn and cynicism’. Politics in the accepted form are out:

‘Those of us who want to do something face a more fundamental problem: how to strengthen the conviction that we have the potential for changing our circumstances. Whether this is done through appealing to self-interest or idealism or a belief in some higher purpose than survival is neither here nor there. There is a need to regroup all those who understand that when human beings cease to play for high stakes, to explore and to take risks or try to transform their circumstances, the world becomes a sad and dangerous place.’

This is, of course, an implicit rejection of Marxism. By appealing to people on the basis of ‘self-interest or idealism or a belief in some higher purpose than survival’, and trying to round up all those interested in playing ‘for high stakes’, exploring or taking risks, Füredi is effectively negating the Marxist axiom that the working class is the universal class through which the interests of humanity as a whole can be expressed; that through the working class seizing power and leading the fight for socialism, the liberation of humanity can occur. The working class as the potential liberator of society is rejected in favour of an amorphous agglomeration of people who are in favour of trying ‘to transform their circumstances’, a vague concept which can mean anything to anyone. Accepting (as he does) that classes still exist is of no help here, as his seemingly magnanimous concession to today’s class-riven society may at first suggest. If this new strategy is not based upon a particular class, then any class is eligible to join in.

Although he’d written the introduction to the RCP’s reprint of the Communist Manifesto a couple of years back, in his editorial in the March 1998 LM, Mick Hume assures readers that he’s not writing yet another commemoration of this now obsolete work. Nevertheless, it’s well worth looking at the Manifesto, because of what Marx wrote in it about the critical-utopian socialists who appeared during the early years of capitalism. Marx said that because of the undeveloped nature of the system, they could see class antagonisms and the ‘action of the decomposing elements in the prevailing form of society’, but the proletariat ‘offers to them the spectacle of a class without any historical initiative or any independent political movement’. He went on to say that these people, wishing to improve the lot of ‘every member of society’, appeal to society as a whole ‘without distinction of class’, and end up appealing to the ruling class: ‘For how can people, when once they understand their system, fail to see in it the best possible plan of the best possible state of society?’

As the twentieth century draws to a close, LM recognises that classes still exist, but the damage inflicted on the labour movement is so great that it in effect sees the proletariat as a class ‘without any historical initiative or any independent political movement’. Moreover, if we are to regroup all those who understand the need ‘to play for high stakes, to explore and to take risks or try to transform their circumstances’, then why not appeal to those who have some clout in society?

But who, exactly? Time and again LM has informed us that the capitalist class has lost confidence in itself and its system, and hides behind the banalities of mission statements. (Maybe, but it still knows how to attack the working class. But who wants to read about the class struggle and other boring remnants of the past?) If we are to believe what we read in LM, those with real influence in society, those who are in the vanguard of the culture of low expectations, are those whom the magazine attacks the most — the liberal media stars, the ‘politically correct’ brigade, the massed ranks of counsellors, social workers, anti-smoking campaigners, non-governmental organisations, and so on, whose misanthropic and pessimistic attitudes have corroded society as a whole.

So where can the former members and supporters of the now-defunct RCP go now? Organising events like the recent three-day conference on free speech with a wide assortment of media personalities, famous novelists, stand-up comedians, fashionable artists and computer games designers may keep it going for a bit. There’s scope for individual members or supporters in carving out a career in the academic or media world, having a book published, or getting a website put on-line, but just what sort of longer-term perspective the group can possibly have is unclear. It seems that the former RCP is operating as some kind of umbrella organisation for a slew of think-tanks on a wide range of topics, largely concerning the media, censorship and regulation. Whilst cultural issues are obviously an important area for study, you can’t maintain for long anything resembling a political organisation solely on these grounds.

As for ideological direction, the editorial of the March 1998 LM says that its agenda is ‘based on a firm belief in the much-maligned human and individual potential’. Fair enough in and of itself, it is woefully inadequate for any coherent political orientation, and, having rejected Marxism and thus losing the theoretical stability that it provides, the ex-RCP may well fragment with bits flying off in all manner of strange directions. Because the RCP eschewed the usual left-wing tactics of critical support for and entry into reformist organisations, it is unlikely that many of its adherents will end up following the course of many disillusioned Marxists into the byways of reformism.

One possible trajectory is right-wing libertarianism. As I mentioned in the last New Interventions, not a little of what appears in LM is disturbingly reminiscent of this trend, a political cul-de-sac if ever there was one, but one that could appeal as happily as liberalism or Marxism to ‘a firm belief in the ... human and individual potential’. Stripped of any concept of class-based collectivity, the reinvigoration of subjectivity and the individual called for by LM could easily in practice result in the disinterment of that classic petit-bourgeois myth, the rugged individual.

How long can the former RCP continue down its chosen road? Although small organisations, not necessarily of a political nature, can produce a magazine for years, decades even, without much evidence of means of support, LM’s very professional production doesn’t come cheap, and its recent evolution must have taken a heavy toll on its circulation figures, as there cannot be many people willing each month to read an ever-increasing number of tracts on an ever-decreasing range of topics. Assuming that the organisation remains in one piece, I can’t see LM attracting any wealthy sponsors who will help keep it going. Nor can I see any political or intellectual current in Britain adopting the former RCP as its think-tank in the way that New Labour has used the Marxism Today wing of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Even if the ITN court case doesn’t finish LM off, lack of direction and a declining audience could well do so.

If the ex-RCP does not fall apart, its recent development and the absence of any obvious political perspectives will almost certainly lead to many of its remaining adherents drifting away out of politics altogether. Many will feel that there is little point in working in an organisation that has no clear objectives, and will use their talents in areas that they’ll see as more personally rewarding. If the admission by former RCP leader Rob Killick in the March 1998 LM that he wishes to emulate Bill Gates in being ‘successful, rich and clever’ is typical of his colleagues, this implies that it was not particularly ‘clever’ to have spent all those years flogging papers on street corners, attending interminable meetings, seeking out contacts and paying good money after bad in dues, when one could have been involved in so many other enjoyable and perhaps more lucrative endeavours.

Of course, the RCP’s renunciation of Marxism is not the first of its type, nor, unfortunately, is it likely to be the last. It’s not unknown for the organisations that have the most accurate but pessimistic prognoses to end up junking revolutionary politics, and the RCP’s assessment of the state of the labour movement at the beginning of the 1990s was considerably more accurate than those of other groups, if also more pessimistic. Then, in a typically one-sided way, it proceeded to view the decrepit state of the labour movement as the demise of the working class as a potential revolutionary force, and came to the stunningly original conclusion that Marxism is obsolete. From opposite ends of the left, Living Marxism and Marxism Today drew the same dismal conclusion! The contrast between the RCP of yore and its fading into oblivion is a nicely ironic illustration of its theory of the ‘culture of low expectations’.

Left-wing groups that are perceived as having gone off the rails often slough off fragments claiming to act in the groups’ true tradition. Once or twice, a group’s leader has drifted off into unwelcome territory, leaving behind, as Max Shachtman did, a number of erstwhile supporters claiming fealty to the leader’s self-betrayed heritage.

Neither of these criteria applies to the RCP, even though its withdrawal from working-class politics was more rapid and thoroughgoing than anything we’ve seen in many a decade. Whilst the party has shrunk considerably, its leading and secondary cadre appear to have remained intact, suggesting that there has been remarkably little dissension over what is not a minor tactical shift or a strategic rethink, but a fundamental political and philosophical reorientation. One cannot rule out the possibility that there might have been some grumbling, perhaps amongst those not so heavily involved in the media and culture arenas, but there have been no visible signs of it in LM. Anyway, disgruntled RCP members and supporters have usually disappeared off the political scene, rather than attempt to form or join another organisation.

Never popular, to put it mildly, with other left-wingers, the RCP did do some high quality theoretical work that often earned the praise of otherwise hostile critics, and it did challenge many of the left’s sacred cows, and pointed out quite a few of its weaknesses. Although it will be tempting for people to joke about the original RCP of the 1940s being a tragedy, and the recent one being a farce, now that the latter has openly repudiated its entire political tradition, and entered upon the road to almost certain oblivion, it will be a shame if there is nobody around to keep people aware of the positive aspects of its past.

0 notes