#svoboda

Text

This article is more than 8 years old.

Washington's role in Ukraine, and its backing for the regime's neo-Nazis, has huge implications for the rest of the world

W

hy do we tolerate the threat of another world war in our name? Why do we allow lies that justify this risk? The scale of our indoctrination, wrote Harold Pinter, is a "brilliant, even witty, highly successful act of hypnosis", as if the truth "never happened even while it was happening".

Every year the American historian William Blum publishes his "updated summary of the record of US foreign policy" which shows that, since 1945, the US has tried to overthrow more than 50 governments, many of them democratically elected; grossly interfered in elections in 30 countries; bombed the civilian populations of 30 countries; used chemical and biological weapons; and attempted to assassinate foreign leaders.

In many cases Britain has been a collaborator. The degree of human suffering, let alone criminality, is little acknowledged in the west, despite the presence of the world's most advanced communications and nominally most free journalism. That the most numerous victims of terrorism – "our" terrorism – are Muslims, is unsayable. That extreme jihadism, which led to 9/11, was nurtured as a weapon of Anglo-American policy (Operation Cyclone in Afghanistan) is suppressed. In April the US state department noted that, following Nato's campaign in 2011, "Libya has become a terrorist safe haven".

The name of "our" enemy has changed over the years, from communism to Islamism, but generally it is any society independent of western power and occupying strategically useful or resource-rich territory, or merely offering an alternative to US domination. The leaders of these obstructive nations are usually violently shoved aside, such as the democrats Muhammad Mossedeq in Iran, Arbenz in Guatemala and Salvador Allende in Chile, or they are murdered like Patrice Lumumba in the Democratic Republic of Congo. All are subjected to a western media campaign of vilification – think Fidel Castro, Hugo Chávez, now Vladimir Putin.

Washington's role in Ukraine is different only in its implications for the rest of us. For the first time since the Reagan years, the US is threatening to take the world to war. With eastern Europe and the Balkans now military outposts of Nato, the last "buffer state" bordering Russia – Ukraine – is being torn apart by fascist forces unleashed by the US and the EU. We in the west are now backing neo-Nazis in a country where Ukrainian Nazis backed Hitler.

Having masterminded the coup in February against the democratically elected government in Kiev, Washington's planned seizure of Russia's historic, legitimate warm-water naval base in Crimea failed. The Russians defended themselves, as they have done against every threat and invasion from the west for almost a century.

But Nato's military encirclement has accelerated, along with US-orchestrated attacks on ethnic Russians in Ukraine. If Putin can be provoked into coming to their aid, his pre-ordained "pariah" role will justify a Nato-run guerrilla war that is likely to spill into Russia itself.

Instead, Putin has confounded the war party by seeking an accommodation with Washington and the EU, by withdrawing Russian troops from the Ukrainian border and urging ethnic Russians in eastern Ukraine to abandon the weekend's provocative referendum. These Russian-speaking and bilingual people – a third of Ukraine's population – have long sought a democratic federation that reflects the country's ethnic diversity and is both autonomous of Kiev and independent of Moscow. Most are neither "separatists" nor "rebels", as the western media calls them, but citizens who want to live securely in their homeland.

Like the ruins of Iraq and Afghanistan, Ukraine has been turned into a CIA theme park – run personally by CIA director John Brennan in Kiev, with dozens of "special units" from the CIA and FBI setting up a "security structure" that oversees savage attacks on those who opposed the February coup. Watch the videos, read the eye-witness reports from the massacre in Odessa this month. Bussed fascist thugs burned the trade union headquarters, killing 41 people trapped inside. Watch the police standing by.

A doctor described trying to rescue people, "but I was stopped by pro-Ukrainian Nazi radicals. One of them pushed me away rudely, promising that soon me and other Jews of Odessa are going to meet the same fate. What occurred yesterday didn't even take place during the fascist occupation in my town in world war two. I wonder, why the whole world is keeping silent." [see footnote]

Russian-speaking Ukrainians are fighting for survival. When Putin announced the withdrawal of Russian troops from the border, the Kiev junta's defence secretary, Andriy Parubiy – a founding member of the fascist Svoboda party – boasted that attacks on "insurgents" would continue. In Orwellian style, propaganda in the west has inverted this to Moscow "trying to orchestrate conflict and provocation", according to William Hague. His cynicism is matched by Obama's grotesque congratulations to the coup junta on its "remarkable restraint" after the Odessa massacre. The junta, says Obama, is "duly elected". As Henry Kissinger once said: "It is not a matter of what is true that counts, but what is perceived to be true."

In the US media the Odessa atrocity has been played down as "murky" and a "tragedy" in which "nationalists" (neo-Nazis) attacked "separatists" (people collecting signatures for a referendum on a federal Ukraine). Rupert Murdoch's Wall Street Journal damned the victims – "Deadly Ukraine Fire Likely Sparked by Rebels, Government Says". Propaganda in Germany has been pure cold war, with the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung warning its readers of Russia's "undeclared war". For the Germans, it is a poignant irony that Putin is the only leader to condemn the rise of fascism in 21st-century Europe.

A popular truism is that "the world changed" following 9/11. But what has changed? According to the great whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, a silent coup has taken place in Washington and rampant militarism now rules. The Pentagon currently runs "special operations" – secret wars – in 124 countries. At home, rising poverty and a loss of liberty are the historic corollary of a perpetual war state. Add the risk of nuclear war, and the question is: why do we tolerate this?

---

The following footnote was appended on 16 May 2014: The quotation from a doctor who says he was "stopped by pro-Ukrainian Nazi radicals" was from an account on a Facebook page that has subsequently been removed.

#neo nazis#nazi ukraine#ukraine conflict#us imperialism#us politics#putin#svoboda#odessa massacre#russia

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your research has focussed on the transformations of the Ukrainian political field since the 2014 Maidan uprising. What type of rupture did this represent? What new forces entered the arena, and what happened to the old ones?

The euromaidan was not a rupture in the sense of a social revolution. As my colleague Oleg Zhuravlev and I have written, it shared features with other post-Soviet uprisings and also with those of the Arab Spring in 2011. These were not upheavals that led to fundamental social changes in the class structure—nor even in the political structure of the state. Instead they were mobilizations that helped to replace the elites, but where the new elites were actually factions of the same class. The Maidan revolutions in Ukraine—the 2014 Euromaidan was the last of the three—were similar. These are, in a sense, deficient revolutions: they create a revolutionary legitimacy that can then be hijacked by agents who are not actually representative of the interests of the revolutionary participants. The Euromaidan was captured by several agents, all of whom participated in the uprising and contributed to its success, but who were very far from representing the whole range of forces involved or the motivations that drove ordinary Ukrainians to support Euromaidan. In this sense, while responding to the post-Soviet crisis of political representation, the Euromaidan also reproduced and intensified it.

Predominant among these agents were the traditional parties of the opposition, represented by, among others, Petro Poroshenko who became President of Ukraine in 2014. These oligarchic parties were structured around a ‘big man’, on patron-client relations: lacking any other model, they reproduced the worst features of the cpsu—heavy-handed paternalism, popular passivity—voided of its legitimating ‘modernity project’. Another smaller but very important agent was the bloc of West-facing ngos and media organizations, which operated more like professional firms than community mobilizers, with the lion’s share of their budgets usually coming from Western donors. During the uprising, they were the people who created the image of the Euromaidan that was disseminated to international audiences; they were primarily responsible for the narrative about a democratic revolution that represented the civic identity and diversity of the Ukrainian people against an authoritarian government. They gained strength in relation to the weakening Ukrainian state, which was first disrupted by the uprising, then thrown into further disarray by Russia’s annexation of Crimea and by the separatist revolt in Donbas, backed by Moscow—and by Ukraine itself becoming more dependent on the West.

Then there were the far-right groups—Svoboda, Right Sector, the Azov movement—which, unlike the ngos, were organized as political militants, with a well-articulated ideology based on radical interpretations of Ukrainian nationalism, with relatively strong local party cells and mobilizations on the streets. Thanks to the violent radicalization of Euromaidan, and then to the war in Donbas, these far-right parties were armed and could pose a violent threat to the government. When the Ukrainian state weakened and lost its monopoly over violence, the right-wing groups entered this space. Western states and international organizations also gained increasing influence, both indirectly—through their funding of civil-society ngos—and directly, because they provided credit and military help against Russia, as well as political support. These were the four major agents that grew stronger after the Euromaidan—the oligarchic opposition, the ngos, the far right and Washington–Brussels.

And those who lost?

Those who lost power were, first, the sections of the Ukrainian elite—let’s call them political capitalists, in the Weberian sense: exploiting the political opportunities their offices provided for profit-seeking—organized in the Party of Regions, which backed Viktor Yanukovych. After the Euromaidan, the party collapsed. These oligarchs, as they are usually called, were politically reorganized; but they retained control over some of the crucial sectors of the Ukrainian economy, so the Forbes list of the richest people in Ukraine was amazingly stable. Before and after the Euromaidan revolution, the only person on the Top Ten list who made a career change was Poroshenko—a sign of how little change there was in the way the economy was working.

The other significant actor that lost out was the Communist Party of Ukraine—and the left in general. But the Communists specifically were banned in 2015, under the laws on decommunization. These were the legal grounds for suspending the activities of the cpu, and also some of the marginal communist parties. In 2012, the cpu won 13 per cent of the vote, so it was a considerable part of Ukrainian politics. In 2014, they didn’t get into parliament, thanks to the loss of Crimea and the Donbas, which were their electoral strongholds. And the next year, they were suspended.

In the interview you gave NLR in 2014, you described how in the political struggles of 2004–14, the Orange parties would try to pull the constitution towards a more parliamentary setup, and the Party of Regions would pull it back to a more presidential one. What happened after 2014 to the constitutional balance, and the relative importance of parliament and president?

After 2014, they rolled back to the more parliamentary-presidential model that worked after the ‘Orange revolution’, and which Yanukovych cancelled in 2010 soon after he was elected the president. On the formal level, in 2014, the president was weakened and parliament was supposedly stronger. The figure of the prime minister, who was chosen by the parliamentary deputies, became more important. But what did not change was the ‘neopatrimonial’ regime, as it is often called in the literature of post-Soviet studies: the informal patron-client relations that dominate politics. It is quite normal to speak of clans in this regard—to say someone is in the ‘clan of Poroshenko’, or ‘clan of Yanukovych’. These informally structured groups, whose relations are hidden from the public, have more influence on how real politics works in our country than the formal clauses of the constitution. So despite the fact that the position of the presidency was formally weakened, Poroshenko was still the most influential politician in the country, able to push more or less what he wanted through parliament.

How did the composition of the parliament change in 2014?

There was a major change with the October 2014 parliamentary elections. Five pro-Maidan parties formed the ruling coalition—Poroshenko’s party, Arseniy Yatsenyuk’s People’s Front, Yulia Tymoshenko’s Fatherland and two others. It had a constitutional majority to begin with; but then, very quickly the coalition started to crumble. Poroshenko did not want to recognise the collapse of the coalition because that would mean having to hold new elections in which his party would perform worse than in 2014. And so, for several years, it was more like a conjunctural coalition, where his people had to manage the problem of getting majority votes.

What was Poroshenko’s agenda?

When he was elected in 2014, Poroshenko wasn’t seen as a representative of the radical wing of Euromaidan. But he was operating in the context of the new nexus of post-Maidan forces, in which, as I’ve said elsewhere, the interaction of oligarchic pluralism with a civil society that lacked institutionalized political or ideological boundaries between the West-backed ngos and the far right, combined with the practically absent left wing, led to a process of nationalist radicalization. The competing oligarchs exploited nationalism in order to cover the absence of ‘revolutionary’ transformations after the Euromaidan, while those in nationalist-neoliberal civil society were pushing for their unpopular agendas thanks to increased leverage against the weakened state.

Poroshenko promised before the elections that he would quickly establish peace in Donbas, and some perhaps voted for him for that reason. But within a few weeks, he had made a U-turn: instead of starting the negotiations with the separatists, he intensified the Anti-Terrorist Operation against them. The idea was to try to take over Donbas militarily. That strategy was defeated by the covert intervention of the Russian Army in August 2014, and that’s how the Minsk process started, first in September, and then in February 2015, after another escalation and defeat of the Ukrainian forces. The Minsk agreements specified a ceasefire, Ukrainian recognition of local elections in the separatist-controlled areas, the transfer of control over the border to the Ukrainian government, and a special autonomy status for Donbas within Ukraine, including the possibility of institutionalizing the separatist armed forces.

Who were the people standing up in favour of the Minsk Accords, and who was against? If this was the one chance of a peaceful settlement, why were they never implemented?

The people who were openly supportive were the opposition segment, mainly, the parties that were the successors to the Party of Regions, which were oriented towards the eastern and southern voters, particularly citizens in the Kiev-controlled parts of the Donbas, for whom the implementation of the Accords heralded the end of the war. For many other parties, Minsk was, at best, something that Russia had forcibly imposed on Ukraine. The argument was: we needed to stick with Minsk, because if Ukraine were to withdraw from the Accords, the West might lift the post-2014 sanctions against Russia. But at the same time, they were quite openly saying that they were not going to implement the political clauses of the Minsk Accords. Many argued that a politically integrated Donbas could block Kiev being able to implement a future Euro-Atlantic integration course, despite there being no mention in the Accords of such a veto. The only leverage Donbas would acquire would be the ability to blackmail Ukraine with the threat of secession, which would be easier to pull off than it had been in 2014. There was no discussion of how practically to prevent this. The Kiev government would also have had to discuss details of autonomy status with the leaders of the Donbas republics, whom they only ever referred to as ‘terrorists’ or ‘Kremlin puppets’. The general logic of the Minsk Accords demanded recognition of significantly more political diversity in Ukraine, far beyond the bounds of what was acceptable after the Euromaidan. So, Russia accused Ukraine of lacking any desire to implement the political clauses of the Accords. Ukraine accused Russia and the separatists of violating the Accords by organizing local elections themselves and by distributing Russian passports among Donbas residents. Meanwhile, the death toll in Donbas grew.

Although in the end it appeared to be Putin who put an end to the Minsk Accords by recognizing the independence of the Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics in February 2022, there had been multiple statements from Ukrainian top officials, prominent politicians and those in professional ‘civil society’ saying that implementing Minsk would be a disaster for Ukraine, that Ukrainian society would never accept the ‘capitulation’, it would mean civil war. Another important factor was the far right, which explicitly threatened the government with violence should it try to implement the Accords. In 2015, when parliament voted on the special status for Donetsk and Lugansk, as required by Minsk, a Svoboda Party activist threw a grenade into a police line, killing four officers and injuring, I think, about a hundred. They were showing they were ready to use violence.

How much did the fighting in the Donbas dominate the politics of this whole period? In the West, it was portrayed at the time as just another frozen conflict, although the casualty figures are quite high—some 3,000 civilian deaths. Was it on the tv news every evening?

It was a very important issue, of course. There was no stable ceasefire before 2020, so practically every day there were shellings or shootings, someone would be killed on the Ukrainian side or on the separatist side. Reports about casualties and shellings were regular news items. But only a minority of Ukrainians, besides Donbas residents and refugees, were directly affected by the war.

Putin claims the hard right dominated the Ukrainian forces in the Donbas.

They never dominated there, no. They were definitely a minority of the units. Some claim the Azov Battalion was one of the most combat-ready units in the National Guard; perhaps so for a period in 2014–15, but not necessarily afterwards. I haven’t studied the military in the Donbas closely, so these evaluations could be wrong. But what I know for sure is that Azov was definitely special; there was nothing else like it—a unit with a political agenda, affiliated to a political party, to a paramilitary organization, to summer camps training children, starting to develop an international strategy, inviting the Western far right to come to Ukraine—‘let’s fight together’—creating a kind of ‘Brown International’. Die Zeit published a major investigative article which situated Azov at the centre of the global extreme-right networks. But Azov was just one regiment. Most of the Ukrainians who were fighting in the Donbas were not in politicized units.

But there was another phenomenon. Azov was integrated into the National Guard structure under the Ministry of the Interior, headed for years by Arsen Avakov, another of the pro-Euromaidan oligarchs. There were other armed factions that originated from the Right Sector, the radical nationalist coalition that became famous during the Euromaidan, that were not integrated, but which coordinated with the Ukrainian Army—what we might call wild groups that could do things the Army command would prefer not to do. But even those groups were a small part of the Ukrainian forces fighting in Donbas.

What was the role of the deep state in this period? Did civic freedoms grow or shrink under the post-Maidan government?

One of the main narratives about the post-Euromaidan Ukraine was the rise of an inclusive civic nation, finally unifying the East and West of the country, and of a vibrant civil society pushing for democratizing reforms. Together with Oleg Zhuravlev, I have shown that the unifying trends were paralleled by polarizing trends; that the post-Euromaidan civic nationalism did not undermine but empowered ethnic nationalism; that inclusion and expansion of democracy for some meant exclusion and repression for others.\ In this process of redefining what ‘Ukraine’ is about politically, a large tranche of political positions supported by many Ukrainians were moved beyond the boundaries of acceptability, according to this new articulation of the Ukrainian nation. So, if before 2014, ‘pro-Russian’ meant a large political camp supporting Ukraine’s integration into Russia-led international organizations such as the Eurasian Union—or even joining the Union State with Russia and Belarus—after this camp collapsed in 2014, the ‘pro-Russian’ label was inflated and often used to stigmatize positions such as support for Ukraine’s non-aligned status and pragmatic cooperation with both West and East, as well as scepticism about Euromaidan outcomes, opposition to decommunization or restrictions on the use of the Russian language in Ukraine’s public sphere.

So, a wide range of political positions supported by a large minority, sometimes even by the majority, of Ukrainians—sovereigntist, state-developmentalist, illiberal, left-wing—were blended together and labelled ‘pro-Russian narratives’ because they challenged the dominant pro-Western, neoliberal and nationalist discourses in Ukraine’s civil society. The stigmatization was, of course, not only symbolic but could lead to online targeting campaigns, often initiated by ‘patriotic’ bloggers who made their public careers by identifying and harassing the ‘enemies within’ and which were amplified by civil society or paid Internet-bots. Occasionally, it ended in actual physical violence, usually conducted by radical-nationalist groups. In the end, it helped to legitimate sanctioning the opposition media and some politicians in 2021.

So this ideological shift principally represented a move towards a nationalist, anti-Russian agenda?

There were other groups that were also specifically targeted by the far right, like feminists, lgbt, Roma people, the left. By 2018–19, when I was still in Kiev and involved in organizing leftist media and conference projects, we were having to operate in a kind of semi-underground manner, never publishing the location of our ‘public’ events, with very careful preliminary checking of everyone who registered for events to see whether they might be some kind of provocateur, people from the far right who had come to disrupt the event.

What did the Poroshenko administration actually achieve?

Poroshenko had moved increasingly towards the nationalist agenda by the end of his rule. Where the post-Maidan government actually got most done was in the ideological sphere: decommunization; empowering a nationalist historical narrative; Ukrainianization; restrictions on Russian cultural products; establishing the Orthodox Church of Ukraine independent of Moscow (but subservient to the Constantinople Patriarchate). These were the planks that the Ukrainian hard right had campaigned on before the Euromaidan uprising; and although the nominal far-right politicians were not present in the post-Euromaidan governments in any significant way, this became the ruling agenda. But it would be simplistic to say that these were the positions of the far right alone, because they were legitimized within the broader bloc of national-liberal civil-society. Demands that before the Euromaidan were seen as very radical suddenly became universalized, at least on the level of what we might call the activist public, although they were often not actually supported by the majority of society.

Another issue was symbolic identification with Euro-Atlantic integration. Ukraine’s 1996 Constitution affirmed the principle of non-alignment. But starting from 2014, Poroshenko and his allies pushed for a change to this, which they could achieve thanks to the constitutional majority of the pro-Maidan parties. The constitutional amendments were passed by parliament in 2018 and signed into law by Poroshenko in early 2019 as a part of his electoral campaign. So now, in a country that may never become a member of nato, the Constitution says that the state’s ‘strategic course’ is full membership of nato and the eu.

Before the 2019 elections, Poroshenko also campaigned heavily on the language issue, he pushed laws that significantly restricted the use of Russian language in the public sphere and education. By the time of the elections he was indeed seen as the leader of the nationalist cause. It was not surprising that he lost so heavily with this agenda in 2019, when Zelensky won by 73 to 25 per cent.

Why would Poroshenko fight an election campaign on these issues, if they were so unpopular?

The dynamics of the deficient Euromaidan revolution could be behind this poor and puzzling choice. Poroshenko has never been an ideologically committed nationalist. He co-founded the Party of Regions and served as a minister in Yanukovych’s government; there have been scandals that his family speaks Russian at home, that he continued to do business in Russia after 2014. Following Euromaidan, Poroshenko was trapped between two opposing agendas: on the one hand, increasingly popular, though disorganized and inarticulate, expectations of post-revolutionary change; on the other, unpopular yet articulate and powerful demands from national-liberal civil society. Nationalist radicalization of the ideological sphere was, for Poroshenko, an easier way of delivering some ‘revolutionary’ change than proceeding with reforms that would have undermined the competitive advantages of his own faction among the political capitalist class. Appeals to nationalism also served to silence ‘unpatriotic’ criticism and to divide the opposition. When the Rada voted to change the constitution regarding nato and the eu, support for nato was at about 40 per cent in Ukrainian society. So, this was not something that was pushed by the majority of voters, or that answered to a logic of ‘we must do something popular before the election’. Poroshenko was pushing projects that were popular among the activist citizens—but not the majority of voters.

Similarly with ‘decommunization’. Once the government had defined what this actually meant, polls showed that Ukrainians were not very interested in renaming the streets and cities or banning the Communist Party. At the same time, they were not ready to defend the Communist Party, because they did not see it as particularly relevant to their politics. But they were not supporters of decommunization either; they were passively against it, though not actively resisting it. The legitimacy of this agenda within the activist civil-society public was much higher than within Ukrainian society at large.

How did Ukraine’s ideological and geographical divisions evolve in the post-2014 period? What happened for example in a traditionally Russia-oriented city like Kharkov?

Up until the Russian invasion, Kharkov hadn’t changed that much. The Russian invasion is now drastically changing the identities and perceptions of Ukrainians, but this is very recent. What emerged after 2014 in Kharkov, and in the larger cities of the southeast, was a somewhat stronger middle-class, civil-society layer, with an outlook much like, let’s say, western Ukrainian politics, but in contrast to—again, as I’ve explained before, this is a misleading and stigmatizing label—the ‘pro-Russian’ attitudes of the majorities in those cities. There was a disjunction between the activist citizens, who were taking part in rallies, writing for the press, blogging, Facebooking, and the people who were coming to the voting booths and electing the mayors, the local councils. The Mayor of Kharkov, Hennadiy Kernes, was shot in the back by some sniper in 2014 and seriously injured—he was in a wheelchair—but he continued to be re-elected until his death in 2020. Right after the Euromaidan he went to Russia and maybe consulted with people there. He came back and took a position loyal to Ukraine—he didn’t support the separatist revolt. He was quite popular in Kharkov and won significant support; he didn’t have any real competition. Another striking fact: according to the opinion polls, outside the western regions, pro-nationalist attitudes had a very clear correlation with affluence: the higher people’s incomes were, the more nationalist and pro-Western their views. In the western regions, there was no such correlation—nationalism had become rooted among the wide layers of society. But in the central, eastern and southern regions, the more middle-class you were, the more nationalistic and pro-Western you were likely to be.

Would you correlate that to other sociological differences between western and eastern Ukraine?

It’s a question that still needs a lot of research, because it relates not only to how Ukrainian civil society was emerging, but to post-Soviet civil societies in general. For the layers who were protesting against Lukashenko, against Putin, but were unable to mobilize the majority of their societies against the authoritarian rulers, partially it involves a class divide; but in Ukraine it also overlaps with national-identity and regional divides. In the western regions, you wouldn’t see this class difference, because that kind of nationalism had been domesticated there for many decades. But in other places, Ukrainian nationalism was more of a middle-class phenomenon—which is of course very different from western European nationalism, which at present is more working-class.

How does Europeanism fit in?

In the post-Soviet countries, again, Europeanism means something different. Pro-eu people in western Europe would definitely keep a distance from the far right. But in the post-Soviet countries, this unusual mixture of nationalism, neoliberalism and pro-eu attitudes can work very well, as an ideology of the activist public.

What sort of alternative did Zelensky offer in 2019, compared to Poroshenko?

The 2019 elections were unprecedented. Ukrainian election results are usually very close: when Yanukovych won against Tymoshenko in 2010, for example, there were just three points between them: it was 49 to 46 per cent. The difference between Yushchenko and Yanukovych in 2004 was also very small, which allowed Yanukovych to steal the election—kick-starting the Orange Revolution. But by 2019, Poroshenko had huge disapproval ratings. Nearly 60 per cent of Ukrainians were saying they would never, ever vote for him. So Zelensky was able to unite a huge majority against Poroshenko; and what seemed even more hopeful was that Zelensky was winning in almost every region in Ukraine, except the three Galician regions in the west where nationalism was strongest, and where Poroshenko won. And so, there was some hope that Ukraine might finally be united. On the left, many did have hopes that with Zelensky there would be more space to breathe. I don’t regret supporting him in 2019; I still think that was the right thing to do. Whatever happened next, Zelensky’s landslide alone undermined consolidation of Poroshenko’s authoritarianism. It was also a huge blow to national-liberal civil society, which had rallied around Poroshenko, and felt quite disoriented when they appeared in the ‘25 per cent’ camp of the political minority, after claiming for several years that the whole nation was united around their agenda. It also created political momentum to claim that the interests of the actual majority in Ukraine were not represented by the people speaking on behalf of the nation, which the old and new opposition parties attempted to seize.

How did the Zelensky government unfold?

After Zelensky won the presidential election in April 2019, he called snap parliamentary elections for July. It was a smart move because his Servant of the People party, which had been created from scratch, won an overall majority—again, this was unprecedented in Ukrainian post-Soviet politics—so he was able to concentrate power in the central authorities. There were discussions about whether to have snap local elections as well; mayors play an important role in Ukrainian politics, and Zelensky’s party would then have complete control if he tried to take some sensitive decisions, like, for example, implementing the Minsk Accords. But having snap local elections was more difficult to justify from the legal point of view. The success of the first prisoner exchanges between Ukraine, Russia and the Donbas in September 2019 contributed to his popularity, because it seemed that Ukrainian politics might be moving in a different direction. Zelensky had over 70 per cent approval ratings and a high level of trust in the polls. There was a window of opportunity to move forward with the Minsk Accords; there were active discussions of the so-called Steinmeier Formula that would provide an algorithm on how to implement the Accords. They were able to agree a temporary ceasefire which at least lasted for a significantly longer period than earlier ones had.

Then what happened?

It very soon became clear that not only was Zelensky’s party not a real party, that this populist leader never had a populist movement behind him, but that he didn’t even have a real team that was capable of proceeding with any consistent policies. His first government lasted for about half a year. He then fired his chief of staff and there was continual turnover in ministerial positions. The lack of a serious team meant that Zelensky quite quickly fell into the same trap as Poroshenko, prey to the most powerful agents in Ukrainian politics: the oligarchic clans, the radical-nationalists, liberal civil society and the Western governments, all pushing for their specific agendas, and the inflated mass expectations about radical changes after an ‘electoral Maidan’ that finally brought ‘new faces’ to the government. Within this trap, Zelensky was trying to build his own ‘vertical of power’, a typical informal ‘chain of command’ in post-Soviet politics. But he was not especially successful in that. Possibly we could analyse it as a kind of weak Bonapartism or Caesarism: an elected leader who tried to overcome these cleavages—attack the left, attack the right, attack the nationalists, attack the ‘pro-Russians’—but did so quite erratically, and without consolidating his regime, ended up creating a mess and alienating many powerful figures in Ukrainian politics by the start of 2022.

Who are the people whom he has appointed to the key positions: the minister of the economy, minister of defence, foreign affairs, and so on? Do they come from his own party, or somewhere else?

His own party was created in a different way, so it was not of much use when filling ministerial positions. In the first government, there were many people from pro-Western ngos. But Zelensky soon saw that they were not actually competent to run the Ukrainian economy. People with whom Zelensky had worked in tv—producers, actors, his personal friends—took some of the important positions. For example, the head of counter-intelligence is someone who was personally connected to Zelensky. Later he took on people who had less of a pro-Western ngo profile, but offered some basic competence in government. Sometimes they were seen as connected to the oligarchic groups—for example, the Prime Minister, Shmyhal, worked for some time for Akhmetov. It is unlikely that he was under the influence of Akhmetov; but at that moment he was seen as a sign of a ‘normal’ politics returning to Ukraine: we are getting rid of those incompetent guys from ngos, and starting to get more real functionaries into the government.

Zelensky was still in the process of creating a real team, with people coming from different sources—sometimes connected to the West, sometimes connected to himself, sometimes to oligarchic groups. By the start of the war, it was not yet clear that he had actually managed to build that ‘vertical of power’. It was beginning to look more and more of a mess; and quite dangerous. From Putin’s perspective, if Ukraine is in a mess, run by a weak and incompetent president, then isn’t this a good time to achieve his goals?

What happened to progress on the Minsk Accords?

Poroshenko and the nationalists had begun a so-called anti-capitulation campaign in 2019, protesting against implementation of the Minsk Accords, although they didn’t have much backing. According to the polls, only a quarter of Ukrainians supported it, and almost half explicitly said they didn’t. At the same time, Azov and other far-right groups were disobeying Zelensky’s orders, sabotaging the disengagement of Ukrainian and separatist forces in Donbas. Zelensky had to go to a village in Donbas and parlay with them directly, even though he is the Commander in Chief. The ‘moderate’ anti-capitulation people could use the protests of the hard right to say that implementation of the Minsk Accords would mean a civil war because Ukrainians wouldn’t accept this ‘capitulation’, and so there would be some ‘natural’ violence.

You’ve said that the hard-right groups were actually quite small, while Poroshenko had just been electorally annihilated. What else prevented Zelensky from carrying out his mandate?

The prospect of nationalist violence was real. But the question remains: why didn’t Zelensky build an internal and international coalition in support of the Minsk Accords? Explicit and active support for the full implementation of the Accords by Western governments would have been a powerful signal to pro-Western civil society. Some people would say that by 2019 the Accords were unpopular—although they did have majority support in 2015, when they were signed, and there was a hope for peace. But by 2019 people were seeing them as ineffective at changing anything in the Donbas. However, neither Poroshenko nor Zelensky had ever seriously campaigned to increase the popularity of the Accords as much as they actually campaigned for the no less controversial and unpopular land market reform or various nationalist initiatives. Finally, France and Germany were not that active in pushing Ukraine to do more about the Accords and the Obama and Trump administrations certainly did not support the agreement as they could have.

- VOLODYMYR ISHCHENKO, “TOWARDS THE ABYSS.” New Left Review. 133/134. Jan/Apr 2022

#volodymyr ishchenko#new left review#ukraine#ukrainian politics#euromaidan#ukrainian civil war#decommunization#ukraine-russia conflict#azov battalion#academic quote#svoboda#ukrainian far right#clientilist politics#ukrainian oligarchs#russia-ukraine war 2022#donbas

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hi everyone, we are Elise Galmard, Lead ... https://www.xtremeservers.com/blog/banishers-ghosts-of-new-eden-meet-lost-ghosts-and-determine-their-fate-in-haunting-cases/?feed_id=120701&_unique_id=65c1a31c53b6b&Banishers%3A%20Ghosts%20of%20New%20Eden%20%E2%80%93%20Meet%20Lost%20Ghosts%20and%20Determine%20Their%20Fate%20in%20Haunting%20Cases

0 notes

Text

Živý člověk informuje všechny soudce, právníky, bankéře, zákonodárce, orgány činné v trestním řízení a všechny veřejné činitele a služebníky

Vatikán se před mnoha staletími stal vládcem Země, aby zotročil lidi. Panství a nyní státy světa byly vybudovány podle systému svěřenství. Státy nebyly založeny na vzájemné rovnosti lidí, ale na domněnce, že jsou příliš hloupí, nemajetní a proto potřebují vedení a později dokonce byli prohlášeni za mrtvé nebo ztracené na moři podle zákona Cestui que vie act (info naleznete v kanonickém právu Canon 2036 počínaje) Aby se člověk stal OSOBOU, byl použit trik.

Kouzelné slovo zní:

"domněnka práva"! Pokud neexistují platné zákony, pak lze alespoň předpokládat, že existují. To je pravda. Je to trik! V právu se předpokládá, že člověk je osoba. To stačí! Dále se předpokládá, že ten, kdo nereptá nebo neodmítá, souhlasí. Klasická smlouva založená na tichém souhlasu. To je totiž základem fiktivního právního systému! První domněnkou právního systému tedy je, že ten, kdo nic neříká, souhlasí. Druhá domněnka je, že člověk je osoba. Třetí domněnkou je, že zákony a stanovy se vztahují jen na lidi, a na to navazuje dalších 80 milionů domněnek! Aby unikli tomuto vědomému podvodu, řeknou jednoho dne, že vy lidé jste to tak chtěli. S tím jste souhlasili. Zákony platí a s vaším tichým souhlasem se staly platnými a vymahatelnými. I přestože s tím nesouhlasíte, stalo se to proto, že se identifikujete jako osoba patřící svému majiteli. Nyní už to víte, neboť je to napsáno v zákonech, o kterých ani nevíte, že existují a neznalost zákona neomlouvá! Všechno v naši společnosti se stalou smlouvou a smlouvy jsou skutečně platné, i když jejich existence se jen předpokládá. Vznikají z nevědomosti a mlčení. Zanikají teprve tehdy, když jsou soudně zpochybněné, odmítnuté a vyvrácené, a teprve tehdy z nich nic nezůstanete. Celý svět je postaven na podvodném systému. Ale jelikož ve vesmíru existují ještě vyšší síly, Vatikán také vytvořil mezery, jak uniknout. Svobodná vůle člověka nesmí být porušena!

Canon 2056

Pokud se zjistí, že soukromý skrytý trust byl vytvořen na falešných předpokladech, tak trust okamžitě ztratí veškerý majetek, pokud se muž nebo žena uvedení v rodném listě prohlásí za osoby, které mají tělo, mysl a duši.

Canon 2057

Jakýkoli správce nebo exekutor, který odmítnul okamžitě rozpustit Cestui Que (Vie) Trust držený nad osobou, a navrátit ji její pravomoci, byl vinen z podvodu a zásadního porušení povinnosti správce AIF, což si vyžádalo jeho okamžité odstranění a potrestání. Zdroj „Canonum De Ius Positivum“ Zlom nastal 21. června 2011 zrušením římského práva! Od 21. června 2011 byl Romanus Pontifex úředně zrušen prostřednictvím Rite Mandamus a Rite Probatum; číslo veřejné listiny 983210-331235-01004. Tímto je všechna jurisdikce Římské říše na Zemi neplatná. Všechny Cestui Que Vie-Trusty jsou zrušeny k 15. srpnu 2011 prostřednictvím Rite Probatum Regnum a Rite Mandamus. (Veřejný záznam dokumentu č. 983210-341748-240014) To zahrnuje zrušení Trustu a Úřadu známého jako Aeterni Regis a "Věčné koruny" neboli "Koruny" spolu se všemi jejími odnožemi, uplynutím platnosti všech zúčtovacích listů, rodných listů, úmrtních dluhopisů a pohledávek včetně orgánů Banky pro mezinárodní platby (BIS).

Papež František vydal 11. července 2013 z vlastního podnětu Motu proprio, nejvyšší právní nástroj na světě, s účinností od 1. září 2013, a následně zrušil imunitu všech soudců, prokurátorů, advokátů a "vládních úředníků". Na základě tohoto papežova motu proprio mají být nyní soudci, advokáti, bankéři, zákonodárci, orgány činné v trestním řízení a všichni veřejní činitelé a zaměstnanci osobně zodpovědní za odebrání domů, aut, peněz a investic skutečných příjemců trustu, za zbavení svobody, podvody, obtěžování a transformaci svěřených prostředků skutečných příjemců. Tento dokument vydaný papežem je historicky nejvýznamnějším a nejdůležitějším zákonem, který uznává Zlaté pravidlo jako nejvyšší autoritu.

Zlaté pravidlo jako nejvyšší zákon znamená: „Všichni lidé jsou nadaní univerzálními právy a nikdo nestojí mezi nimi a Stvořitelem. Nic není nad tímto zákonem“. Pro nás lidi je to jediný platný zákon, dokud nebude vyvrácen! Na audienci u Mezinárodního měnového fondu 18. ledna 2016 papež František souhlasil s vrácením veškerého majetku Vatikánské banky lidstvu. Svatý Římský stolec dokončil potřebný právní proces zřeknutí se moci, a tím se z vlastního rozhodnutí vzdal vlády nad lidstvem a nároků na světový majetek.

Všechny církevní nebo světské orgány, které si nárokují jurisdikci v obchodních záležitostech s námi lidmi, jsou podle UCC 3-501 povinny vyvrátit uvedená tvrzení a prokázat svou jurisdikci nad lidskou duchovní bytostí, předložit smlouvu podepsanou mokrým inkoustem nebo smluvně dokázat zákonnost jejich nesouhlasu.

Rozhodnutí UCC:

1. září 2012 ( UCC doc. no 2012096074, 2012114586, 2012114776) v UCC doc. no 2012096074 ze dne 9. září 2012, též známého jako PROHLÁŠENÍ A NAŘÍZENÍ se uvádí, že:

"Všichni lidé nyní jednají jako individuální subjekty, bez podnikové záchranné sítě a s plnou odpovědností. V případě, že jakákoli fyzická osoba prosazuje jménem banky nebo "vlády" zneplatněné a zablokované jednání, které způsobí jiné fyzické osobě jakoukoli škodu, jako je: popsáno v tomto dokumentu, nese absolutní a neomezenou odpovědnost sama za sebe."

.... dobrovolníci v armádě.... "Zatkněte a vezměte do vazby všechny korporace, jejich zástupce a zaměstnance, kteří vlastní, provozují a podporují soukromé peněžní systémy vydáváním, zpeněžováním a aktivací zákonných systémů prosazování práva." V případě, že jakákoli fyzická osoba podnikne kroky jménem zneplatněné a zabavené banky nebo "vlády" a způsobí škodu jiné fyzické osobě, nese absolutní a neomezenou odpovědnost. Podle práce, kterou vykonali správci OPPT, nyní všichni lidé jednají jako jednotlivci, bez záchranné sítě společností a s plnou osobní odpovědností za VŠECHNY SVÉ ČINY, které podléhají:

právnímu systému obecného práva, chráněnému a udržovanému v provozu Zákonem o VEŘEJNÉM POŘÁDKU UCC č.j. 1–103.

— Ustavující charty vlády zrušeny: SKUTKOVÁ PROHLÁŠENÍ: UCC Doc# 2012127914

Říjen 2012 (UCC doc. no 2012114776) FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF USA a všechny banky s ní přímo nebo nepřímo spojené, včetně údajných národních bank, jsou zablokovány právnickou osobou The One People Public Trust 1776, přičemž listina je zapsána v District of Columbia, Washington USA, viz: WA DC UCC Doc No. 2012114776 známá také jako PRAVÝ ÚČET.

"Prohlášení a neodvolatelný příkaz ke zrušení všech bank a každé listiny zakládající bankovní instituce podle mezinárodních předpisů (BIS), zrušení organizačních schémat, které se na ně vztahují, a jsou:

od nich odvozeny, a odstranění všech příjemců včetně korporací se soukromým režimem, které vlastní LIDSKÁ TĚLA s odkazem na státy, které provozují, podporují a jsou vinny z napomáháním soukromému kapitálovému režimu, vydáváním, vybíráním, prosazováním legislativy a zaváděním otrockého systému do praxe. 2000 . (OMISSIS).2000 . REKVIZICE PRÁVNÍ HODNOTY PROSTŘEDNICTVÍM NEZÁKONNÉHO ZASTOUPENÍ."

Březen 2013, (UCC Doc. no 2013032035)

Právní postup zakládá jedinečnost "JA JSEM", ruší všechny právní subjekty zvané osoby, fyzické osoby, právnické osoby atd., které byly dříve založeny údajnými zákony údajných 194 států, a také ruší všechny formy zprostředkování a Důvěry (fiduciární dispozice) vůči JEDNOTĚ svévolně založené ve prospěch jejích údajných zástupců (politických a náboženských) na Zemi, čímž obnovuje suverenitu každé lidské bytosti, která si na ni činí nárok.

Poznámka: Všechny tyto dokumenty jsou registrovány na úřadu vlády UCC ve Washingtonu DC v databázi k nahlédnutí zde: https://archive.org/details/OPPTUCCFILINGS/

S lidmi, co se vydávají za vládu a předvádějí nám celá ta léta divadlo zvané volby to evidentně ani nehlo a jdou dál jako by se nic nestalo. Nikomu nic oficiálně nesdělili, ale něco se přece jen změnilo. Je to tvar jména v dokladech v roce 2012. Tento tvar již neznamená živého člověka. Píše se na hroby nebo je v názvu firem a neoznačuje živé lidi, protože vlastnictví lidí přes svěřenectví bylo zrušeno. Za dob ČSSR a po té ČSFR byl tvar jména Ján Novák. Při mimochodem protiprávním rozdělení republiky bez referenda 327/1991 a dalšího porušení zákona 424/1991 se nám změnil tvar jména na Jan NOVÁK a vydržel až do již zmíněného roku 2012.

Významy tvaru jmen osob v dokladech co jsem našel:

pepa novák - živý muž, má všechna práva udělená Stvořitelem a patří pod přirozené právo

Pepa Novák - capitis diminutio minima - národnost, členství v rodině, je omezen na svobodách a právech, které má člověk v přirozeném právu. Má práva a povinnostech vůči státu

Novák Pepa - válečný stav (nom degueru)

Pepa NOVÁK - capitis deminutio media - ztráta občanských práv a občanství/rodinného členství (právnická osoba = prohlášen za mrtvého-ztraceného na moři podle zákona cestu que ví)

PEPA NOVÁK - capitis deminutio maxima - ztráta svobody, občanských práv a rodinné příslušnosti (mrtvá právní fikce = neživý majetek korporace, cár papíru nejste to vy)

I když je podle mezinárodního práva otroctví zakázáno v jakékoli podobě, naše dobrovolnost a naivita stále umožňuje těmto podvodníkům určovat nám práva a vybírat daně. A hlavně jim to umožňuje to, že nás nechávají při každé identifikaci s OP o sobě dobrovolně říci, že jsme majetek firmy ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA (stát byl převeden na firmu a rovněž všechny úřady) až do smrti. Osoba je fikce patřící korporaci a vše co na ni registrujete je dar této korporaci. Proto si nemůžete nechat auto na díly. Všechno jste dali korporaci. Majetek i děti přes rodné listy. Takový člověk co se vydává za osobu je tedy otrokem a dá se s ním dělat spoustu věcí. Naopak právní imunita byla ve vyšší jurisdikci zajištěna.

Takto to chodilo.

Nyní po právních změnách uvedených uvedených výše jsou všechny příkazy osobám neplatné, protože jsou všechny fiktivní osoby zrušeny. Vymáhání jakýchkoli příkazů a rozkazů určených zrušeným osobám po lidech je nyní bez jejich souhlasu nezákonné!!!

Na základě všeho předchozího se domnívám, že covid-19 byl spuštěn právě kvůli tomu. Vzhledem k tomu, že z tohoto otroctví lze právně uniknout prohlášením, že jste živý člověk. Imigranti, kteří jsou živí a bez dokladů zachráněni na moři se netestují ani neočkují (články o tom lze dohledat). Člověk se a změněnou DNA již není člověk a pravděpodobně se ho lidská práva netýkají. V roce 2013 soud rozhodl, že lidská DNA nemůže být patentována, protože jde o přírodní produkt. Dospěl však k závěru, že pokud by byl lidský genom (orgán nebo buňka) modifikován mRNA vakcínami, může být genom patentován. Zdá se, že tito podvodníci nepotřebují nutně lidi, stačí jim mutanti a nepochybuji o jiných nárocích o kterých nikdo neví.

Proč o tom všem lidé neví a proč se tyto informace postupně dozvídají z alternativy? Protože mainstreamová media vlastní ti samí globální parazité, kteří vás chtějí nadále zotročovat.

Jste svobodní živí lidé a nikdo nemá právo vztahovat své požadavky na vaše těla, majetky a svobodnou vůlí ducha. Celé lidstvo bylo osvobozeno OPPT skrze skutková prohlášení UCC.

Překlad redakční úprava: Martin Kirschner (www.vipnoviny.cz), Zdroj: jedenzajednohovsetciza.sk

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Volia

'Given the rigid and demanding norms of community life, it is not surprising that, at least subconsciously, peasants yearned to escape them, to break away and begin a new life of volia (freedom). Many young men did so, either by simply establishing a new household or, more radically, by fleeing to the frontier and becoming a brigand or perhaps joining the Cossacks.

Volia is not freedom as that is understood in modern democratic societies, for which another word exists: svoboda. Rather, volia is the absence of any constraint, the right to gallop off into the open steppe, the "wild field" (dikoe pole), and there to make one's living without humble drudgery, by hunting or fishing, or if necessary by brigandage and plunder. Volia does not recognize any restriction imposed by the equivalent freedom of others: it is nomadic freedom rather than civic freedom.'

Russia and the Russians, by Geoffrey Hosking

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Stanislav Novotný se ptá Milana Urbana, co nebezpečného má za lubem neschopná koalice ODS, Pirátů, STAN, TOP 09 a KDU-ČSL vládnoucí v Praze a jdoucí na ruku úchylné politice EU https://ocemsemlci.cz/o-cem-se-mlci-milan-urban-2/?feed_id=1265

#aktivisté#blokovánídopravy#byty#čističkaodpadníchvod#doprava#elektromobilita#fantasmagorie#KDUČSL#MilanUrban#motoristé#ODS#PIRÁTI#Praha#Pražskýokruh#primátor#Školství#SPD#STAN#StanislavNovotný#Svoboda#TOP09#Ukrajinci

1 note

·

View note

Text

Snaha uvěznit nás

Loutkovodiči vás chtějí uvěznit v zajetí negativních rezonančních polí. Zprávy ve sdělovacích prostředcích nejsou nic jiného než sbírka negativních sdělení, pomocí kterých vás systém udržuje ve stavu malosti, deprese a beznaděje. Dozvídáte se o nezaměstnanosti, povodních a klimatických katastrofách, o energetické krizi, krachu bank, útocích teroristů a možnosti, že se sami staneme dalším cílem.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

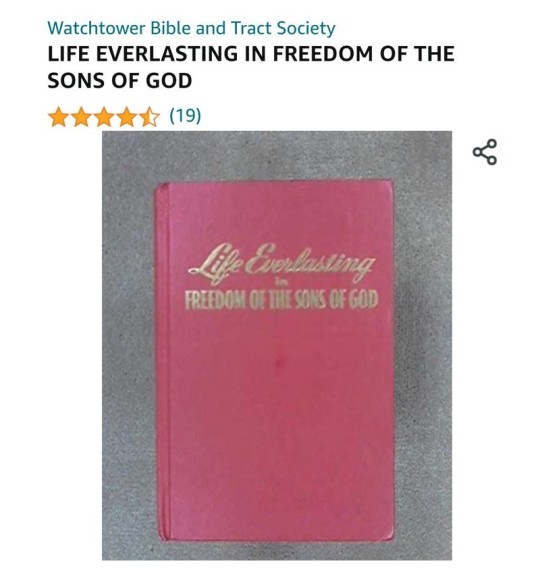

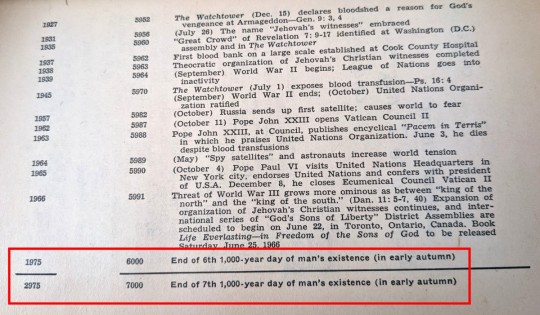

Rok 1966 – kniha: Věčný život ve svobodě Božích synů (čeština 1972)

V roce 1966 vydali svědkové Jehovovi knihu Věčný život ve svobodě Božích synů.

Tato kniha obsahovala „biblickou chronologii“, která ukazovala, že po roce 1975 má přijít 1000 let Božího království. Mezi roky 1975 a 2975 mělo být sedmé tisíciletí lidské existence, které mělo být obdobím tisíciletého panování Krista.

To, že tato změna neoddiskutovatelně přijde, říkali svědkové Jehovovi v propagačních materiálech takto:

Lidstvo již dosti dlouho trpělo pod vládou útisku a nespravedlnosti. Jsou nějaké vyhlídky na brzkou nápravu situace? […]

Navzdory tomu všemu se spravedlnost již brzo ujme vlády nad celým lidstvem. […]

Bůh však může nastolit spravedlnost pro všechny, a také to učiní. Stojíme tváří v tvář přesvědčivým důkazům, které ukazují, že Bůh se k tomu chystá v blízké budoucnosti.

[…] Poznej, jak můžeš být mezi těmi, kteří budou mít užitek z překvapivých změn, které již zanedlouho nastanou.

Přečti si hodnotnou pomůcku ke studiu Bible: VĚČNÝ ŽIVOT VE SVOBODĚ BOŽÍCH SYNŮ

Jak víme, sliby ohledně roku 1975 se nesplnily a svědkové Jehovovi --- skoro po 50 letech --- se čím dále více vzdalují od rétoriky ohledně „věrohodné biblické chronologie“.

Je totiž zřejmé, že to všechno jsou spíše nevěrohodné lidské bludy a falešné názory náboženských pomatenců. Jehova opět splnil to, co slíbil.

Proboha!

0 notes

Text

Jan Svoboda. Untitled (Folk carving, a deer) from the series Essays on Sculpture, 1966.

498 notes

·

View notes

Text

Petr Cyperský a vévoda Štěpán Bavorský, nedoceněná to loď česká i svatořímská.

#Karlštejn boyfriends#Nenapadá mě lepší shipname#Někdo nápady?#Noc na Karlštejně#čumblr#obrození#Petr Cyperský#Vévoda Štěpán Bavorský#Waldemar Matuška#Miloš Kopecký#Karel Svoboda#Jaroslav Vrchlický#Národní obrození#České#Obrozenci#České filmy#Čumblr loď#Say gex#lumírovci#ťumblr

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

„Google jsou Iluminati“ Poslední internetový příspěvek Davida Bowieho děsivě prorokovaný na rok 2023

David Bowie byl pravidelným přispěvatelem na bowie.com, fóru jeho oficiálních stránek, a jeho poslední zpráva, napsaná jen několik týdnů před svou smrtí v roce 2016, obsahovala prorocké varování o budoucnosti lidstva.

Bowie psal pod svým pseudonymem „námořník“ a prozradil, že „Google jsou Illuminati“ a varoval, že pokud Googlu dovolíme provozovat internet a kontrolovat tok všech informací, elity promění společnost ve „fašistickou dystopii“.

Než se do toho pustíme, nezapomeňte se přihlásit k odběru novinek a připojit se ke komunitě stejně smýšlejících lidí pro exkluzivní a necenzurovaný obsah.

Sedm let poté, co napsal zprávu na smrtelné posteli, se Bowieho varování pro lidstvo zdá více prorocké než kdykoli předtím.

„Mottem Googlu je b.s. Ničí ten nejskvělejší dar, jaký lidstvo dostalo za posledních 300 let. Google je iluminát. Ilumináti jsou google. Budoucnost pod googlem je fašistická dystopie, na jejich cestě nebo dálnici, není žádný prostor pro disidenty, žádný prostor pro svobodu slova. Google je bota, která vám bude šlapat po tváři celou věčnost. námořník."

Bowie také varoval, že internetový vyhledávač infiltrovala globální elita v rámci jejich plánu zotročit lidstvo. Další zpráva od Bowieho, napsaná ve stejném vláknu fóra, zní:

„Google je hluboký stát. Zapomeňte na konvenční války, zapomeňte na špiony, zapomeňte na zpravodajské agentury, zapomeňte na to všechno. Je to všechno o internetu a Google provozuje internet. Rozhodují o tom, jak se cítíte, co si myslíte, na jaké informace se můžete a nemůžete dívat a nakonec, kdo může nebo nemůže mít názor. námořník."

Bowie, vždy napřed, si v 90. letech osvojil internet. Věřil, že je to ideální platforma pro individuální a tvůrčí svobodu. V roce 1998 spustil BowieNet, poskytovatele internetových služeb, který nabízel telefonické připojení do nového a vzrušujícího online světa svobody a možností.

V době, kdy se velké korporace stále snažily pochopit důležitost internetu, měl Bowie jasnou vizi budoucnosti. BowieNet nabízel necenzurovaný přístup k internetu a byl nadšený z možností, že kyberprostor je bez cenzury a regulací.

„Kdyby mi bylo znovu 19 let, vynechal bych hudbu a šel rovnou na internet,“ řekl tehdy. V 90. letech Bowie pochopil, že se blíží revoluce, ale BowieNet se uzavřel až v roce 2006 a jeho vize budoucnosti internetu výrazně potemněla.

Osobní svoboda, kterou slibovala raná fáze internetu, byla nahrazena něčím, co připomínalo iluminátské vězení pro lidstvo.

Osmnáct měsíců po smrti Bowieho se jeho poslední varování lidstvu o Googlu a Iluminátech ukázalo být stejně prorocké jako jeho předchozí tvrzení o internetu.

Google je v současné době pod kritikou kvůli potlačování svobody projevu, cenzuře internetu, a tomu, že straní elitám a Nového světového řádu.

Bowie věřil, že internet není jen nástroj nebo prostředek. Starý svět a nový svět internetu se spojily a staly se realitou. Kdo ovládá internet, ovládá vše.

V roce 2023 se Bowieho poslední varování pro lidstvo zdá více prorocké než kdy jindy. Klaus Schwab nedávno připustil, že „kdo ovládá AI, bude ovládat všechno“.

A WEF spolupracuje s Googlem ruku v ruce již desítky let. Klaus Schwab v rozhovoru se Sergeiem Brinem, spoluzakladatelem společnosti Google, mimochodem prozradil, že každý bude mít v budoucnu mozkové implantáty jako součást rozsáhlé kontroly matrixu.

Mimochodem, Sergei Brin byl v pátek předvolán Americkými Panenskými ostrovy jako součást vyšetřování případu Jeffrey Epstein-JPMorgan. Ale o tom jste pravděpodobně neslyšeli, protože Google a WEF jsou odhodlány potlačit zprávy, které odhalují hluboké vazby globalistické elity s Epsteinem a dalšími pedofily.

Google a obři sociálních média potlačují obsah z alternativních zpravodajských kanálů, které publikují informace, které nevyhovují jejich agendě. Tvrdí, že to dělají, aby vytvořili lepší svět.

Ale historie ukazuje, že jejich pokusy prodat nám liberální utopii jsou pastí.

Jak varoval Bowie, svoboda slova je nezbytná a politický diskurz je pro demokracii zásadní. Cenzurou oponentů a odebráním jejich práva vyjadřovat se ve společnosti, Google a globalistická elita ženou lidstvo směrem k fašistické dystopii.

Zde jsme odhodláni pokračovat v odhalování zločinů globalistické elity. Ale sami to nezvládneme. Přihlaste se k odběru novinek, sdílejte tento článek s kýmkoli, o kom si myslíte, že by z těchto informací mohl mít prospěch, a připojte se ke komunitě stejně smýšlejících lidí pro exkluzivní a necenzurovaný obsah. Doufám, že vás tam uvidím.

Podívejte:

Překlad: Martin Kirschner (www.vipnoviny.cz), Zdroj: newspunch.com

Read the full article

#davidbowie#decentralizovanýinternet#fašistickádystopie#google#internet#klausschwab#kontrolovanýinternet#světovéekonomickéfórum#svoboda#svobodanainternetu#wef

0 notes

Photo

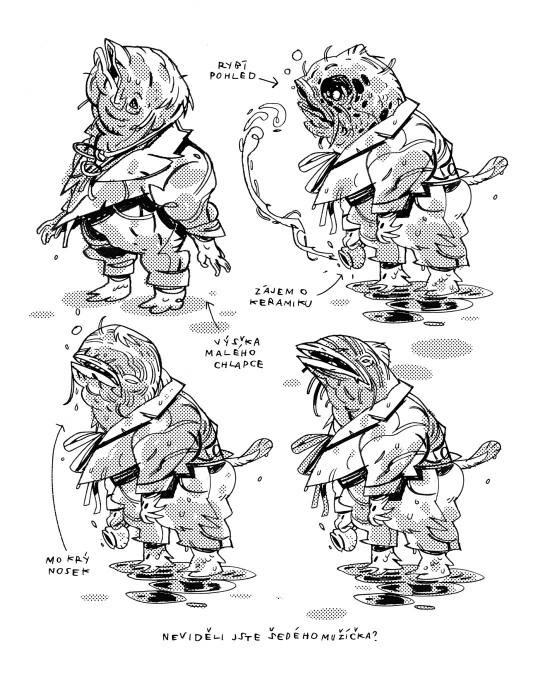

Vodník (let’s say Water Goblin)

86 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Twins, 2016 - by Luna Svoboda, Russian

163 notes

·

View notes