Text

Testimony of a Viticulture and Enology TA at UC Davis

Image via

1 note

·

View note

Text

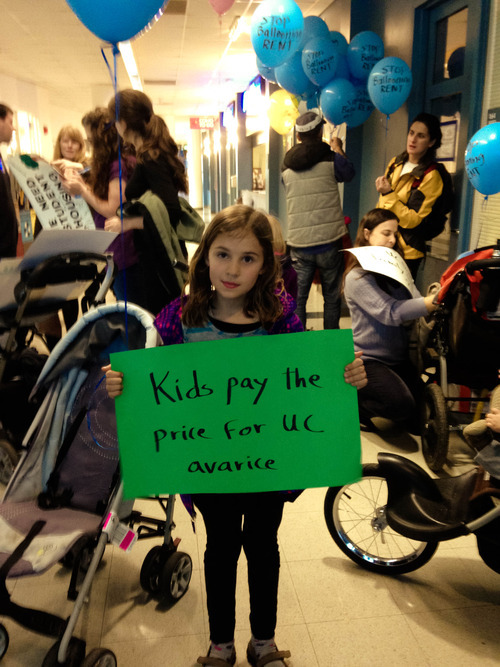

Parents and kids organize for family support at UC

Student-parents at UC Davis marched into the UC Student-Workers' Union bargaining session to give testimony about the need for affordable housing.

Sign the petition to support these families and stop the demolition of the Parks.

Like them on Facebook for more stories from the Parks.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

A professor of Art and Art History exposes the administrative pressure to raise class size at UC:

Departments who do not meet the expectations to teach ever-larger classes face budget cuts and cuts to the number of sections they can offer. As fewer TAs serve more students, it seems this campus will regrettably — and inevitably — move toward only the most superficial education at what is supposed to be one of the nation’s top public universities.

Read on to see her letter about why we need smaller classes at UC now.

#education#public education#UC Davis#University of California#privatization#class size#ta#art history

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

We don't want your checkbooks, we don't want your magic wand, and we don't want your fake apologies. This is your last chance. The students that are here for you will only give you what you ask for: uncensored lived experiences. We're not afraid to tell it like it is. We demand your resignation.

Video of Napolitano’s last “listening and learning” tour student meeting at UC Berkeley, February 13th.

You can listen to the rally outside at Blum Center!! The powerful words by students to Napolitano starts at 5:30.

Folks from the Undocumented, API, African American, Latin@ and Queer Community all spoke out!!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Testimony from a UC Davis TA

I care about class size not just because of pedagogical concerns but academic relationships as well. Currently I have two sections, one of which is about 25% smaller than the other, and the atmospheres in each class are like night and day. Particularly for folks in commonly marginalized groups, smaller classes open up spaces to speak and be heard, to have ideas and confidence validated and learning potential affirmed. And in the relational aspect of teaching, the difference here is also palpable. Having time to spend with students on their academic and general concerns can make forging a personal connection possible. Connections like these with instructors made education seem relevant and even possible for me as an undergraduate, and as an instructor I feel we owe our students nothing less. Our working conditions, of which class size is an integral part, are their learning conditions, and they deserve the time and attention small class sizes afford.

-Amanda Modell, graduate student in Cultural Studies, UC Davis

#class size#uaw2865#contract2013#teaching#public education#UC Davis#University of California#pedagogy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Testimony from a UC Davis Grad Student Researcher

My name is Karin Root. I am a PhD student in Sociology and currently work as a GSR for the Middle East/South Asian Studies department. The reason why I work as a GSR is because I can no longer work as a TA because of the 18-quarter limit.

In 8 years in the program, including summers, I have TAed or read 27 times, out of which only 2 where repeats. While I don't hold lectures, I have to know the material well enough to be able to teach my students and do the grading. Not only do I have to attend lecture, do the readings, prepare and run sections, but also do the grading and give them feedback.

Almost all of the grading in the social sciences at UCD is being done by TAs, and with increasing class sizes it becomes very difficult to do our work, especially when we are under time pressure. For example, I had one class of 93 students and had almost 650 short essays on 7 different questions to grade for the final. I asked the instructor twice to help me grade in order to submit the grades before the end of the quarter, but the instructor refused. Finally, I ended up not grading two questions and giving all students full points on them.

I especially care about and reach out to struggling students, making personal contact with them, and working with them one-on-one to build their confidence, pass the class, and not drop out of university. Often struggling students have other work and family commitments that interfere with their school work. They need to learn how to do research, find information from different perspectives, present their findings and take a position, and support their arguments. As a state-supported university it is our mission to help students become critical analytical thinkers and the kind of employees that our state needs in the 21st century. With the increasing class size to TA ratios we can't give them the kind of help that they need.

As graduate students we need living wages, affordable housing, summer fellowships, and more grants, credit for MAs, elimination of the 18 quarter rule, etc. As a GSR I clear a little under $1,600/mo and spend 75% of this on rent for me and my son. I also have $80,000 in student loans and don't qualify for any more. Like other students who spoke, I can only survive because my parents support me. I used to tell my students, "come talk with me if you are interested in grad school." I don't do that anymore. We are expected to do significant work on our research over the summer, but we usually have to work, and that interferes with our progress. We also don't have any pension or social security. Indeed, if I worked for McDonald's at least I would have social security and disability coverage.

In the end, it is a matter of priorities. There is money for new buildings and high administrative salaries; there should be money for living wages, benefits, fellowships, and smaller class sizes. We need more money to be able to survive and to do our research and work as academic student workers!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Testimony from a UC Davis TA

Testimony from UC Davis Sociology PhD student Emily Breuninger.

I want to begin by setting out that being a TA is my absolute favorite part of graduate school. I feel most alive and engaged with my own education when I am helping others understand it. To me, there is no greater joy than seeing my students' faces light up when they finally understand course concepts. Unfortunately, the high TA-to-student ratio forced upon me by UC management has rendered it impossible for me to serve as a competent grader, much less educator for these students.

Last quarter, I had the misfortune of TAing for a class of 95 undergraduates. Sociology is a rather writing-heavy discipline, meaning that the course assignments consisted mainly of 6-8 page papers. At the end of the quarter, after finishing all my own coursework, I had three days to grade 95 6-7 page papers. That is about 618 pages, thoroughly read, with individual feedback. I was exhausted, overworked and under a pressing deadline set by the university. As I quickly scanned through the pages, I thought about the hours of labor that went into each student’s paper and was overcome by guilt. I knew that I was not giving my students’ work the attention that it deserved. I am not the only TA that has these problems; a high student-to-TA ratio is unfortunately the norm, and while UC is saving money, the true cost of these cutbacks is wrought out on the quality of education experienced by thousands of graduate and undergraduate students.

As an educator, I want to give my students the time and attention that my position requires. As a student, however, I must also attend to my own coursework and progress. I am unable to attend to both when so thoroughly overburdened by my TA duties. The strain that TAs are put under by large class sizes is a threat to the quality of education espoused by the UC. Neither graduates nor undergraduates are capable of reaching their fullest potential in this environment and it is a shame. I therefore urge UC management to reconsider the class sizes forces upon their student workers.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Testimony from a UC Davis Geology student

Hello, my name is Julie Griffin. I am in my third year of graduate study in the Geology department of UC – Davis. I am here to testify for the rights of graduate students to subsidized housing. I currently live in a two-bedroom apartment in Solano Park with my best friend and her three-year-old daughter. Our rent is 908 dollars per month. The average rent for unfurnished two-bedroom apartments in Davis, according to the 36th annual City of Davis vacancy and rental rate survey, is 1,240 dollars per month. The 332 dollars that we collectively save on rent each month has enabled both of us to start saving money for the future. If I did not have the reduced rent that comes from living in graduate student housing, I would not have been able to start an investment retirement account until after finishing my doctorate degree in my late twenties-early thirties, thus reducing the benefits of interest. My quality of life would substantially diminish if 42% of my paycheck each month were spent on housing and utilities. Subsidized graduate student housing is necessary for students to maintain some semblance of a normal life while in school, studying to become the future workers of higher education.

Most importantly, graduate student housing fosters a sense of community for families. I joke that Solano Park operates under a “communal toy policy” as the grounds are littered with bicycles, sand box supplies, and even rocking horses that all children are welcome to play with. My neighbors and I discuss how growing up in Solano Park would be awesome, because you always have a friend nearby and plenty of playgrounds to enjoy. The events planned by the resident assistants of Solano Park develop this feeling of togetherness even more. Graduate student housing is critical not only for our wallets, but also for our sense of community. Please consider the importance of subsidized graduate student housing while negotiating this deal. Thank you.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Testimony from a UC Davis PhD

My name is Robin Marie Averbeck, and I am a former graduate student of the history department here at UC Davis. I received my degree in June of 2013, 7 years after I came to Davis. During that time, I was witness to the continuing deterioration of teaching and learning conditions here at the UC; witness to the struggle of my fellow graduate students as they tried to stay afloat under such conditions; witness to the callous and dismissive response of the administration to these struggles, and even witness to incidents of violence committed by the administration against students trying to do something about the fact that the public university is currently under attack and in serious danger of dying.

When I come face to face with individuals tasked with being stewards of that public university, however, I always feel a strange sense of irony about what I am doing. For what is at stake here is whether or not the story I witnessed – the story of graduate students struggling to get by while their work was chronically undervalued – is going to be the primary story that gets told. The opposing story, on the other hand – the story we often hear from the administration – is a story of innocence and helplessness. Much like, not coincidentally, the story of white racial innocence crafted by our political culture in the last 40 years in response to the civil rights movement, the story of administrative innocence insists that the administrations of the UC are simply doing their best. In this story, the administration, strangely, has no power to substantially change or challenge graduate student working conditions. In this story, there is, oddly enough, money enough to raise the wages of overpaid administrators with all their apparently excessive talent but no money to significantly raise the wages of graduate students doing the work of teaching students. In this story, the administration has no power to create all-gender bathrooms, although, oddly, it does have the power to license new construction project after construction project. Indeed, time and time again, when it comes to the demands of the workers of the UC, the administration appears oddly powerless. Victims of circumstance, is all. As distressed about the lack of funding for public education as anyone, they assure us.

What I came here today to say is that this story is a lie. Not only does the administration have power to challenge and change these conditions, but it frequently contributes to the arrangements of power and politics that sustains them. If this is otherwise, I ask you, please, to call my bluff. Prove me wrong about your dismissal of the struggles of your graduate students to maintain a decent standard of living by substantially raising their wages – prove me wrong about your dismissal of their struggles with discrimination and injustice by giving them all-gender bathrooms – prove me wrong about your callous disregard for the needs of their families by extending full health coverage to all the children of the graduate student workers of the UC. And prove me wrong about your complicity in the political discourse that sustains privatization by rewarding the students that stand bravely in its way not with riot police but with support and supplies. Please, prove me wrong – because although the story you do spin now is untrue, it is not my wish for it to remain so. For the story I know – the story I have come here today to tell you, and story I have seen unfold over the past seven years – is a story I am so tired of telling.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Testimony from UCLA Graduate student

I am a doctoral student in the department of Gender Studies at UCLA, and I'm in my 3rd year. I'm 33, I've been married for almost 8 years, and I have a three-year-old daughter.

I want to briefly tell management about how things are working out for me and my family on my TA salary. We live in university family housing and pay 66% of my income for rent. It’s very expensive, but way below typical rental rates for my neighborhood, which is about 4 miles away from campus. Before we moved in to university housing, we lived in a cheaper apartment in the same neighborhood. There we paid $1100 for a cockroach-infested apartment with a meth dealer as a next-door neighbor. It was an incredibly unsafe place to live and added to the insecurity we already experience in our daily lives.

You see, my daughter has a neuromuscular disorder and a severe speech disorder. She is in therapy 14 hours a week and has at least one medical appointment each month, in any number of doctor’s offices all over Southern California. The typical cost for childcare in my neighborhood is between $900-1200 a month for fulltime care. Special needs childcare is about twice that. We pay our babysitter $1200 a month for part time care. We mostly pay for this with the money my husband is earning as an adjunct professor – a job at which he earns $936 a month, and which ends this month. I know that the university run childcare and preschool in the housing complex is a little cheaper, about $900 a month, and we are on the waiting list to get in to that. Last time I checked there would be a spot available in three years. Even if we were to get in now, there is no one there who is fluent in sign language, which is what my daughter uses to communicate.

My husband borrowed $18,000 while he was in school at UCLA. We will start paying that back this month. Next month we will also be paying for his health insurance, which is good because of course as an adjunct teacher he is uninsured. At the end of last summer we sat down and looked at all these expenses, and were fortunate enough to be given a choice. We could either borrow $20,000 to get us through this academic year, or we could move into my parents’ house. This was not an easy decision, because my parents live almost 60 miles away from campus. With the therapies, childcare, and generally lack of support we have here, we opted to move.

I’m on the waiting list for 8 different vanpools right now, and if I don’t get in, I will have a 2-3 hour commute each way. I'll need to leave campus everyday by 3:30pm if I want to get home in time to say goodnight to my daughter. If I don't have class or section there is no way I will be able to campus. I won’t be able to attend any special afternoon lectures, and I am concerned about how this distance will affect my ability to remain engaged with the campus community, let alone the ease with which I will be able to coordinate meetings with my committee members. My husband and dad will share the childcare duties. Just saying this now.... This is not an easy choice. But getting even further into debt is not a better option. Borrowing money is just a stopgap until I need to borrow more money, so just I can buy food and pay for childcare.

I know I am so fortunate to have this family safety net, and if it weren’t there, I would have already dropped out. Because this is so hard, and we student workers have to make a lot of really difficult choices to make this work for our lives. Why does working for the university have to be so hard for us? I continue to feel incredibly insecure about how I am going to make this work, how I can teach, study, and parent, without adequate support.

0 notes

Photo

UC is very confused about how much money their TAs make...

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hope the administration understands that this is not just a question of the 'crisis moment.' It's a long-term institutional and political question about the future of public education in the US.

Testimony from a UCSC member:

I would like to make the statement that I've TAed at two other State Universities (Ohio State and University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee), and taught as an adjunct at New York University, and I have never faced working conditions as demoralizing as I have here. I have been in two other unions and was terrified at the idea that we might strike -- this is the first time I have felt that it's our moral duty to strike under these working conditions. We need a living a wage that is on par with other universities and takes into account the obscenely high cost of living in Santa Cruz. We need more full-time faculty hires, so we are not TAing for adjuncts who are as angry and even more isolated than we are (our union should work on organizing with the lecturers), and we need class sizes and workloads that allow us to do our job well. We deserve it and our students deserve it. I hope the administration understands that this is not just a question of the 'crisis moment.' It's a long-term institutional and political question about the future of public education in the US. They have a chance to shape the university of the 21st century and the lives of a generation of thinkers and makers who have already been harshly impacted by the financial crisis. I would encourage them - and us - to think big, be visionary, and make a difference.

0 notes

Audio

If management is so interested in teaching us about our "bad choices," perhaps they need to take this rhetoric to its logical conclusion. Perhaps they should just tell us that we made a bad choice in coming to the UC in the first place.Because management is certainly trying to make that true.

Testimony from Brian Malone

I am a graduate student in Literature at UC Santa Cruz. I have been here for a number of years and I have seen my standard of living decrease over time. I want to talk about how the UC has caused me and my colleagues to lose ground.

In the last contract, we received a 2% raise per year. You can't see me right now, but I'm putting the word "raise" in quotation marks. Here's why. Over the three years under the previous contract, our salary increased by 6%. During that exact same time period, from 2010-2013, the Consumer Price Index increased by 7.3%. Which means that, when taking into account the rate of inflation, we took a 1.3% pay cut under that contract.

Here's something else to take into account. Last year, in June of 2012, the rent on my apartment in Santa Cruz went up by 8%. This past summer, June 2013, my rent increased again by more than 7%. This is an increase of more than 16% in just over one year. During that same period, my salary increased--as you may recall--by 2%.

So that's why I'm losing ground.

Now, from following these current negotiations, I know that management likes to use the rhetoric of choice when TAs talk about how hard it is to live on what the UC pays us. They like to say that parking is a choice and having kids is a choice. And then they compare some of these choices to splurging on a fancy dinner.

And I guess it is true--in the most trivial sense possible--that I've have chosen to live in an apartment in Santa Cruz in which the rent has been raised 16% in the last year. I've chosen to live in that apartment instead of, say, living in the Lit grad shared office or living in my car (and indeed, I know some colleagues who have done those things). But I've chosen instead to live in an apartment and I assume management would consider that another one of my bad choices that they shouldn't be held responsible for--like me spending a lot of money on a fancy meal or choosing to park on campus or if I were to, say, have kids.

So if Management is so interested in teaching us about our bad choices, perhaps they need to take this rhetoric to its logical conclusion. Perhaps they should just tell us that we made a bad choice in coming to the UC in the first place. Because management is certainly trying to make that true.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A collective narrative of trying to make it on $17,000 a year: bargaining testimony from a UCSC student-worker

This is not an exhaustive list, but it’s exhausting.

As academic workers, we teach 20 hours a week, and then we do research for at least 20 to 40 hours a week, in service to the community and the university. We are paid for our teaching work, but the research we do, creating knowledge, is unpaid. We make $17,000 a year. I’m going to say that again. I do this with my students, I say ‘I’m going to say this again, write it down. We make only $17,000 a year.’ We make only $17,000 a year in a town where almost that entire paycheck goes to rent. So today I’m going to talk about how academic workers try to get by on $17,000 a year. These are not just my stories. These are the stories of many. I elicited responses from other graduate student workers, and received this litany of creative, difficult and sometimes illegal ways that we struggle to live; a collective narrative of trying to make it in Santa Cruz on $17,000 a year.

One of the ways that academic workers make it on $17,00 a year is by going into debt – massive and crippling debt. Taking on tons of education debt, until it runs out. This is a tactic I am intimately familiar with. I have taken out education loans, and now I have reached my lifetime limit. Academic workers also get by using multiple credit cards,payday loans, borrowing money from parents (if their parents are in a position to do this), taking out more debt than they’ll ever be able to pay back, going into debt just to handle unplanned or added expenses like car repairs or a new pair of eyeglasses. Taking out summer loans just to go to that required conference. One academic worker wrote: “I used my four credit cards in such a way that I would max one out and then transfer it to another one with a low interest rate offer. I also used the cards to pay utility bills. Eventually, though, the balance transfer offers stopped coming, and just about the time I graduated, I reached the point where all four credit cards are maxed out, leaving me with about $40,000 of credit card debt.”

Stealing is another way that student workers attempt to make ends meet: stealing from supermarkets, Whole Foods, clothing stores, stealing meals from college dining halls.

Service work is another way that we try to live on $17,000. Many of us are taking on second and third jobs. This year, when I reached my limit for financial aid, and I knew my first paycheck wouldn’t arrive until November, I realized I had to take on another job, on top of teaching and doing research. I took a job bartending, and I’m doing that 20 to 30 hours a week right now. Don’t get me wrong. There is nothing wrong with being a bartender. My mother is still doing it at 66 years of age. I think though, when it comes to being able to deliver quality education, that it’s not so good for my students that their teacher is spending that much time in a bar. Other jobs that academic workers are taking: being a taxi driver, working at a winery, working at a farm in exchange for food, waitressing/waiting tables, tutoring (private or through UCSC), hosting an illegal café in my home, babysitting, dog-walking, house-cleaning, doing piecemeal sewing outsourced to me through a tailor, working at the local sex toy store, and being a resident assistant to other grads in graduate housing.

We also make ends meet by slinging our research and analytical skills: including statistical consulting, administrative work for friends/family in the real estate business, selling editing skills, copy editing website translations.

This one is probably one of the longer lists. I call it being outrageously thrifty, to the point of risking one’s health and ability to keep up in school:

Academic workers use food stamps, get food by visiting the food bank on campus, couponing, eating food out of the garbage, eating food from restaurant trash dumpsters, walking around town picking fruit in order to have something to eat, going through recycling trash bins to gather recyclable items to exchange for money. Buying only used books, buying no books at all---only pirated PDFs, buying no books at all---only using library books. Sharing a costco membership with many others, buying in bulk, eating only ramen and burritos daily. One academic worker wrote: “I’ve literally gone hungry.”

Some academic workers participate in the illegal drug economy to help pay the bills: selling a vast array of drugs, growing marijuana, trimming marijuana,selling pot cookies.

Having a partner also is a way that some academic workers are able to make it, relying on a partner to help pay the bills and rent.

Family wealth, although rare, is another. An unlikely and sad story, one academic worker wrote:“In my final year of grad school, I inherited money after two grandparents passed away, which allowed me to get by on my stipend alone” which facilitated completion within normative time.

Many workers talked about selling books, and other items that have sentimental value, in order to make ends meet: selling things one would have rather have kept, selling family jewelry, selling furniture, flea market sales, selling precious books and other family heirlooms.

Academic workers are also risking life and limb: by foregoing health-related procedures that were highly recommended by a doctor, like getting growths removed, dental work, eye-glass prescriptions. The copay and additional fees were just too far beyond budget. One worker states: “I have a health condition and I cannot afford the copays on my TA stipend.”

Additional work at the university is another tactic to make ends meet. This is often precarious work, and subject to departmental approval to work more than the TAship. One student is the intern for the division’s grant analyst. Another writes about readerships: “I've taken on a readership in addition to my ta-ships a couple times. The readerships on top of ta-ing are probably the most draining in this context.” Another academic worker writes: “I kept score of basketball games. Unfortunately, that was also for the university. First they tried to give my job to undergrads, then they stopped paying me altogether. Kinda like being a TA.”

Substandard and illegal housing is especially important to living here in Santa Cruz: Being creative, that is, illegal, with living situations to save money, such as living in a walk-in pantry, garage, campus office, or lab. Sleeping in an office for months or quarters at a time for lack of housing, working a job as a live-in caregiver for folks with disabilities, which provides income and rent, but is a lot of work, renting out my room on airbnb and sleeping on the couch in order to pay rent.Recently, a colleague of mine told me that we don’t even make enough to qualify for low-income housing! You heard that right… we don’t make enough to qualify for low-income housing in Santa Cruz. Go figure. One academic worker talks about their experience: “I lived with up to five undergrads -in partially illegal housing- as well as several other situations that have required my regularly using earplugs to study/write. Earplugs are also often necessary where I live now. And I know illegal housing setups and sketch landlords have been important to my and many other grads' ability to survive here.”

That is not an exhaustive list, but it’s exhausting. I’m exhausted from working a second job just so I can have a job here at UCSC. It’s hard to be a teacher, do my research, and work behind the bar up to 30 hours a week. As you’ve seen, my story is not uncommon. For these reasons, I’m going to push the UAW bargaining team, and our membership, to take this all the way. I’m willing to take it all the way in order to make sure academic workers can live where we work. I have to leave now. I have to go teach. Thank you.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Testimony from a UCSC PhD candidate

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

I’m a graduate student in queer and labor history at UC Santa Cruz. I’ve worked as a teaching assistant numerous times, and I’ve also taught courses on US labor history, queer history, and queer studies at UC Santa Cruz. Both in my studies and my labor activism I focus on queer labor activism– in other words, I look at discrimination faced by queer workers and how queer workers have challenged discrimination in the workplace.

All queer workers face discrimination on the job, but numerous studies* have shown that transgender workers face a disproportionate amount of discrimination at work. Due to this discrimination, according to a study conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality and the Gay and Lesbian Task Force, transgender people are nearly four times more likely to have a household income less than $10,000 per year compared to the general population. 41% of the respondents to the same survey reported having attempted suicide, compared to 1.6% of the general population. 78% of transgender survey respondents reported facing harassment in K-12 schools. Transgender people experience double the rate of unemployment as the general population, and 47% of respondents said they experienced an adverse job outcome, such as being fired, not hired, or denied promotion for being transgender.

One very common way that transgender workers and students face discrimination at the UC, of course, is due to the lack of a sufficient number of all-gender bathrooms. Workers and students at the UC face harassment, intimidation, and, sometimes, violence when attempting to use single-gender restrooms. The UC recently issued a press release on August 21, 2013 lauding its place as one of the most LGBT friendly universities in the US. However, Campus Pride, the organization that creates this list, does not ask about gender neutral bathrooms in academic and administrative buildings. The UC cannot claim to the friendly to transgender workers and students if it refuses to provide more all-gender bathrooms at the UC.

As a member of UAW 2865, I’m helping to organize support, in particular, for our anti-discrimination demands. What’s become very clear to me is that there is widespread support for more all-gender bathrooms at the UC. All LGBT Center Directors at the UC, undergraduate and graduate transgender and queer students, and the LGBT Task Force associated with the UC Office of the President have all expressed strong support for more all-gender bathrooms. We have formed a UC-wide network to organize in support of more all-gender bathrooms at the UC, calling attention to the hypocrisy of UC claims to be LGBT friendly when it is actively discriminating against transgender workers and students.

*For instance: A study conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality and the Gay and Lesbian Task Force is from 2011, with 6,450 respondents, the “most extensive survey of transgender discrimination ever taken.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Audio

This letter is in support of the all-gender restroom demand by the UC Student-Worker Union. At least one all-gender and wheelchair accessible restroom should be installed in each UC campus building. This is a human right, and this is a worker’s right.

I am second-year graduate student enrolled in the sociology program at UC Santa Cruz. I am also a Teaching Assistant for a sociology course here. I started focusing on global water and sanitation issues around five years ago in both work and research, and safe access to toilets and hygiene is a demand people around the world take seriously.

Given the recent recognition of water and sanitation as a human right by the UN and also by the state of California, to say nothing of the obvious benefit to various users, this is a demand the University of California should also take seriously.

Did you know that California was the first state in the nation to designate water (for “sanitary purposes”) a human right? Governor Brown signed the historic bill in September 2012. He made this move after the ground-breaking UN resolution for an international human right to water and sanitation in July 2010. In fact, this year the UN is officially dedicating November 19th as World Toilet Day. They said: “This new annual observance will go a long way toward raising awareness about the need for all human beings to have access to sanitation.”

Sanitation is a question of basic dignity for people in the Global South and in the Global North. And we (UC students, faculty, staff, and visitors) are not exempt. The average adult urinates up to eight times a day and defecates up to three times a day. Still, not all people in the UC system have equal access to restrooms. Families with small children, those with disabilities, caretakers of the elderly, and LGBTQ individuals often walk by restrooms thinking, “is it safe to enter?”

LGBTQ individuals are especially burdened with possible harassment and bullying in gender-segregated restrooms. A 2001 San Francisco Human Rights Commission survey found “41% of transgender respondents reported direct harassment or physical violence in gender-limited public bathrooms.” The Transgender Law Center states “many transgender and non-transgender people have no safe places to go to the bathroom - they get harassed, beaten, and arrested in both women’s and men’s rooms.”

Workers on campus are doubly impacted. With limited time constraints, they might not be able to leave their building to find an all-gender restroom before their section starts or during class breaks.

The UC system should follow the lead of other places providing these essential sanitation rights across North America. Portland, Oregon adopted public restroom design principles calling for all-gender and single-user facilities in public spaces when designing the Portland Loo. All-gender and single-user restrooms designed by an American Restroom Association president won awards in La Jolla, California. The University of Alberta recently converted all single-user restrooms to all-gender restrooms. Penn State University converted 80 single-user restrooms to all-gender restrooms. The majority of restrooms at New College of Florida (Sarasota Campus) are all-gender facilities. These are just a few of the many success stories.

In summary, the UC system is especially well-poised to ensure these critical sanitation rights are met for all workers (and all people) on campuses statewide per Governor Brown’s recent legislation requiring water for “sanitary purposes” and the international recognition of sanitation as a human right. Workers with small children, those with disabilities, caretakers of the elderly, and LGBTQ individuals deserve a working environment that meets their sanitation needs. A minimum of one all-gender and wheelchair accessible restroom in each UC campus building is a both a human right and a worker’s right.

I ask that you honor these rights during UAW 2865 bargaining agreements.

0 notes