#Dick Huemer

Text

Dread by the Decade: Fantasia (Segment: "Night on Bald Mountain/Ave Maria")

👻 You can support or commission me on Ko-Fi! ❤️

Year: 1940

Genre: Animated, Dark Fantasy, Occult, Ghosts

Rating: Approved (Suggested: PG)

Country: United States

Language: Silent

Runtime: 11 minutes 31 seconds

Director: Wilfred Jackson

Writers: Joe Grant, Dick Huemer, Campbell Grant, Arthur Heinemann, Phil Dike

Editor: George Cave

Composer: Modest Mussorgsky

Plot: The devil, Chernabog, summons restless souls and demons to dance upon Bald Mountain.

Review: Though short, this gorgeous segment stands as a shining example of early animated horror.

Overall Rating: 4.5/5

Story: 3/5 - Not really the focus of this piece, but a fun little idea.

Animation: 5/5 - My knowledge of animation is limited, but even I can tell this was groundbreaking. The colors, character movements, and technical skill here are just amazing.

Editing: 5/5 - Smooth and well paced.

Music: 4.5/5 - Though not original to the segment, it fits so well.

youtube

Trigger Warnings:

Mild violence

Nudity

#Fantasia (1940)#Fantasia#Night on Bald Mountain#Wilfred Jackson#American#animated horror#animated#Dread by the Decade#review#1940s

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lonesome Ghosts (1937)

directed by Burt Gillett and animated by Isadore Klein, Ed Love, Milt Kahl, Marvin Woodward, Bob Wickersham, Clyde Geronimi, Dick Huemer, Dick Williams, Art Babbitt, and Rex Cox

#walt disney#disney#lonesome ghosts#1937#classic cartoons#Mickey Mouse#donald duck#goofy#animation#cartoon#burt gillet

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

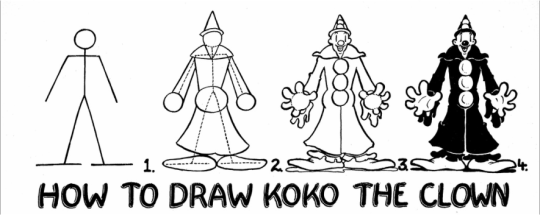

Koko the Clown, created by Max Fleischer and further developed with Dick Huemer.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

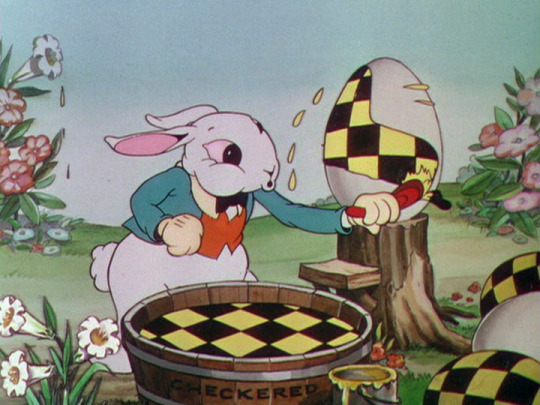

= Walt Disney’s Silly Symphony: Funny Little Bunnies=

Year: March 24, 1934

Director: Wilfred Jackson

Animators:

Art Babbitt

Joe D'Igalo

Dick Huemer

Dick Lundy

Hamilton Luske

Wolfgang Reitherman

Archie Robin

Leonard Sebring

Ben Sharpsteen

Cy Young

Studio: Walt Disney Productions

Music: Frank Churchill, Leigh Harline

Layouts: Hugh Hennessy

Story Outline: A pair of bunnies invite the spectator to join a magical, cute, and sweet bunny land where all bunnies cooperate to create easter decorations. We can see all kind of treats, chocolate bunnies, gigantic chocolate eggs and even baskets. Everything is in this charming spectrum that indicates that this is a mystical place where color comes from rainbow drops.

Award: Venice Film Festival, Golden Medal Winner

Color Process: Technicolor. This technology was very expensive and still in a testing process, so the Silly Symphonies shorts were a crucial point to prove that the three-strip technicolor technique was an improvement in the film industry. In 1932 Burton Wescott and Joseph A. developed the camera with three-strip color process which would offer a full color range, instead of the red and green that had been used before. This camera exposed three color stripes at the same time on top of the black and white film. This technique was created by its own enterprise called Technicolor Motion Picture Corporation, founded by Herbert Kalmus, Daniel Frost Comstock, and W. Burton Wescott. This process was used exclusive by Walt Disney (who made an agreement of exclusivity) up until 1936 so the competition such as the Fleisher Studios were left behind (technology and color wise).

Reception: In general, for the Silly Symphonies, they had a great impact not only as a counter part for the people’s emotion and moral due to the Great Depression, which was awful, it was hard to get a job and any job would just not be enough, still, people would still pay 3.25 dollars to see movies, it was the great escape from reality. Yet again, this time was also a time where the color film was trying to become affordable for studios and being accepted for crowds, a technological competition that never stopped, considering that the first Technicolor movie was consider a fiasco, according to the Fortune magazine. In this magazine review is also revealed that Merian Caldwell Cooper, producer of King Kong (1933) after seeing the silly symphonies was no longer interested in producing in black and white.

Extra: In the case of the “Funny Little Bunnies”, we know that the Great Depression was sinking people’s moral and for so, Disney was creating this happy, magical, it’s all okay projects, but there was also merchandising and adds were also money makers. If I look for the date of the release this short was just before easter meaning appealing for a good selling market, not to mention that by this time, the Disney brand was not only selling on high exclusive products like diamonds but there were also more affordable home friendly items like blackboards.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One week til Dick’s

photo by Rene Huemer

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

75. Pateta e Wilbur (Goofy and Wilbur, 1939), dir. Dick Huemer

0 notes

Audio

(Literary License Podcast)

Fantasia is a 1940 American animated musical anthology film produced and released by Walt Disney Productions, with story direction by Joe Grant and Dick Huemer and production supervision by Walt Disney and Ben Sharpsteen. The third Disney animated feature film, it consists of eight animated segments set to pieces of classical music conducted by Leopold Stokowski, seven of which are performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra. Music critic and composer Deems Taylor acts as the film's Master of Ceremonies who introduces each segment in live action.

Fantasia 2000 is a 1999 American animated musical anthology film produced by Walt Disney Feature Animation and released by Walt Disney Pictures. Produced by Roy E. Disney and Donald W. Ernst, it is the 38th Disney animated feature film and sequel to 1940's Fantasia. Like its predecessor, Fantasia 2000 consists of animated segments set to pieces of classical music. Celebrities including Steve Martin, Itzhak Perlman, Quincy Jones, Bette Midler, James Earl Jones, Penn & Teller, James Levine, and Angela Lansbury introduce a segment in live action scenes directed by Don Hahn.

Opening Credits; Introduction (1.00); Background History (15.06); Fantasia (1940) Film Trailer (18.19); Opening Presentation (21.15); Let's Rate (41.33); Introducing Our Second Feature (43.40); Fantasia 2000 (1999) Film Trailer (46.11); Lights, Camera, Action (48.12); How Many Stars (1:19.57); End Credits (1:24.29); Closing Credits (1:25.46)

Opening Credits– Epidemic Sound – Copyright . All rights reserved

Closing Credits: The Age of Not Believing by Angela Lansbury. From the album Bedknobs and Broomsticks Original Soundtrack. Copyright 1971 Disney Records

Original Music copyrighted 2020 Dan Hughes Music and the Literary License Podcast.

All rights reserved. Used by Kind Permission.

All songs available through Amazon Music.

0 notes

Photo

August 24, 2022 The Creative Multiverse Presents: #AuGhost #AuGhost2022 Day 24 ( Ink) Lonesome Ghosts is a 1937 Disney animated cartoon, released through RKO Radio Pictures on December 24, 1937, three days after Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). It was directed by Burt Gillett and animated by Izzy Klein, Ed Love, Milt Kahl, Marvin Woodward, Bob Wickersham, Clyde Geronimi, Dick Huemer, Dick Williams, Art Babbitt and Rex Cox. The short features Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and Goofy as members of The Ajax Ghost Exterminators. It was the 98th short in the Mickey Mouse film series to be released, and the ninth for that year. #CreativeMultiverse #Disney #WaltDisney #MickeyMouse #art #artwork #artistofinstagram #artist #artistforhire #Custom #create #drawing #drawingaday #draweveryday #illustration #pencil #sketch #ink #colordrawing #Sketchcard #fabercastell #copic #twitchstreamer #cartoon #Animated #blickartmaterials https://www.instagram.com/p/ChtlnWZuYHe/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#aughost#aughost2022#creativemultiverse#disney#waltdisney#mickeymouse#art#artwork#artistofinstagram#artist#artistforhire#custom#create#drawing#drawingaday#draweveryday#illustration#pencil#sketch#ink#colordrawing#sketchcard#fabercastell#copic#twitchstreamer#cartoon#animated#blickartmaterials

0 notes

Text

Lilli e il Vagabondo (1955)

Lilli e il Vagabondo (1955)

Benvenuti o bentornati sul nostro blog. Nello scorso articolo abbiamo parlato di un horror veramente importante, probabilmente uno degli horror più importati della storia che ha segnato un vero e proprio cambiamento nel genere: La notte dei morti viventi. Un film su un gruppo di persone intrappolate in una casa e costrette a difendersi da degli zombi. La storia si approccia in maniera molto…

View On WordPress

#animazione#Barbara Luddy#Bill Baucom#Bill Thompson#Buena Vista#Clyde Geronimi#Dick Huemer#Don DaGradi#Erdman Penner#film#film d&039;animazione#Frank Thomas#Hamilton Luske#Happy Dan The Whistling Dog#Joe Grant#Joe Rinaldi#Lady and the Tramp#Lee Millar#Lilli e il Vagabondo#Louis Pollock#Peggy Lee#Ralph Wright#Recensione#Recensione film#Verna Felton#Walt Disney#Walt Disney Company#Walt Disney Pictures#Ward Greene#Wilfred Jackson

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Movie Odyssey Retrospective

Fantasia (1940)

With production on Bambi postponed, Walt Disney dedicated himself to Pinocchio (1940) and a film featuring animated segments accompanying classical music. Walt’s demands for innovation saw Pinocchio’s budget skyrocket, and the film left Walt Disney Productions (today called Walt Disney Animation Studios) on unstable financial grounds. This laid impossible financial expectations for the latter film – tentatively entitled The Concert Feature – to meet. War halted the possibility of cross-Atlantic distribution as Walt continued to emphasize innovation for each of his features and workplace tensions rose among his animators. What was planned as a glorified Mickey Mouse short set to Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice – Mickey’s popularity was flagging by the mid-1930s, trailing other Disney counterparts and Fleischer Studios/Paramount’s Popeye the Sailor – grew to include seven other segments. The film that became known as Fantasia remains the studio’s most audacious work. Though it built off the visual precedents of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), the volume of artistry for artistry’s sake contained in Fantasia, eighty years later, remains unsurpassed.

After the Philadelphia Orchestra’s conductor/music director Leopold Stokowski offered to record The Sorcerer’s Apprentice for free (he did so with a collection of Hollywood musicians; the English-Polish conductor, a rare conductor who spurned the baton, was among the best of his day), cost overruns on The Sorcerer’s Apprentice led to its expansion as a feature. To provide commentary as Fantasia’s Master of Ceremonies, the studio sought composer and music critic Deems Taylor – who came to Disney and Stokowski’s attention in his role as intermission commentator for radio broadcasts of New York Philharmonic concerts. But both Disney and Stokowski were too busy during the summer of 1938 to brief Taylor on their plans. Stokowski spent that summer in Europe seeking permission for the rights to use certain pieces from various composers’ families (this included visits to Claude Debussy’s widow and Maurice Ravel’s brother); Disney was occupied with the construction of the Burbank studio. After Stokowski returned from Europe in September, Disney asked Taylor to come to Los Angeles to formally discuss Fantasia. Taylor agreed, arriving one day after Stokowski and Disney began their meetings, staying in Southern California for a month.

Over several weeks that September, Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor made the final selections for pieces – suggested by story directors Joe Grant and Dick Huemer (both worked on 1941’s Dumbo and 1951’s Alice in Wonderland) – to be featured in Fantasia. Hours were spent listening to classical music recordings, followed by brainstorming potential visualizations. The meetings were recorded by stenographers, with transcripts (housed at the Walt Disney Archives in Burbank) provided to all three participants. During these meetings, Walt mostly listened to Stokowski and Taylor consider every suggestion by Grant and Huemer:

DISNEY: Look, I really don’t know beans about music.

TAYLOR: That’s all right, Walt. When I first started, I thought Bach wrote love stuff – like Romeo and Juliet. You know, I thought maybe Toccata was in love with Fugue.

During these meetings, an admiring Walt – in addition to gifting a potential last hurrah for Mickey Mouse and to create a film unrestrained by commercial demands – realized he wanted to create a gateway to classical music for those who might not otherwise give such music a chance. Always leading his writing staff in developing stories, Walt felt relieved that he could share this responsibility with Stokowski and Taylor. Free of the storytelling stresses plaguing the Pinocchio and Bambi productions at the time, these tripartite meetings were not beholden to narrative cohesion, allowing the participants to suggest anything that their imaginations conjured. Without the constraints of narrative logic or predictions about what an audience wanted to see, Fantasia became the center of Walt Disney’s passion until its completion.

Nine selections were made by the trio, with one piece later being dropped entirely (Gabriel Pierné’s Cydalise and the Satyr) and another being replaced after its completion. A completed segment for Debussy’s Clair de Lune* was substituted out for Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 (the mythological scenario Walt envisioned for the Pierné reverted to the Beethoven, but more on this later). Over the next few years, Disney’s animators would complete the artwork; Stokowski would study, arrange, and record the selections with the Philadelphia Orchestra (except for The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, which had already been recorded); Taylor would write his introductions to be filmed at the Disney studios.

In almost all of cinema, music accompanies and strengthens dramatic or comedic visuals. Fantasia is the reverse of this relationship. The animation provides greater emotional power to the music – an arrangement that may be startling to viewers unfamiliar with or disinclined to classical music or cinematic abstraction. Fantasia’s opening scenes and piece introductions feature the affable Taylor, who outlines the film’s conceits:

TAYLOR: Now there are three kinds of music on this Fantasia program. First, there’s the kind that tells a definite story. Then there’s the kind that, while it has no specific plot, does paint a series of more or less definite pictures. And then there’s a third kind, music that exists simply for its own sake.

That last kind, also known as “absolute music”, opens Fantasia with Johann Sebastian Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, an organ piece arranged for orchestra (“Toccata” and “Fugue” refer to the musical forms of the piece’s two halves). As James Wong Howe’s (1934’s The Thin Man, 1963’s Hud) gorgeous live-action cinematography of the orchestra (the Toccata) transitions to animation (the Fugue), the audience witnesses Walt Disney Animation’s first, and arguably only, foray into abstract animation – as opposed to abstract stylizations to bolster a macro-narrative – for a feature film. The Toccata and Fugue is a pure visualization of listening to music, as if the animation was improvised. The sequence involves, among other things, string instrument bridges and bows flying in indeterminate space, figures and lines rolling across the screen, and beams of light and obscured shapes timed to Bach’s piece. In these opening minutes, Fantasia announces itself as a bold hybrid of artistic expression in atypical fashion for Disney’s animators.

Next is The Nutcracker Suite by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, which is subdivided into six dances (“Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy”, “Chinese Dance”, “Arabian Dance”, “Trepak”, “Dance of the Reed Flutes”, “Waltz of the Flowers” – these dances are placed out of order, and the “Miniature Overture” and “Marche” which open the suite are not present). Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor made this selection decades before Tchaikovsky’s now-most famous ballet became a Christmas cliché in the United States – it was barely performed in the early twentieth century and is usually regarded, among classical music experts and by the composer himself, as a lesser Tchaikovsky ballet.

History aside, this animated treatment of The Nutcracker utilizes an astonishing array of different animation techniques across all six dances. With The Nutcracker, the Disney animators, for the first time, take a piece with a preexisting story, animate sequences adhering to the music’s essence, yet producing images that have nothing to do with the original material. In Fantasia, The Nutcracker remains a ballet – the sugar plum fairies, racially insensitive mushrooms, fish, and flowers move as if they are on a ballet stage. But there is nothing, in the sense of a narrative through line, to connect all six dances. Set to the changing of the seasons, The Nutcracker contains gorgeously-animated fairies and intricate fish (Cleo from Pinocchio was a testing run for the “Arabian Dance”), climaxing with fractal flurries that look like an antique Christmas card brought to life. Even the racist “Chinese Dance” exemplifies masterful character design – simplicity does not preclude expressiveness. The Nutcracker’s spectacular inclusion improved Tchaikovsky’s standing and his least acclaimed ballet among casual classical music fans.

Based on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s poem of the same, Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice ushers in the Mickey Mouse short that overshadows all others. With the animators’ adaptation closely following Goethe’s poem, Dukas’ original piece is impossible to listen to without imagining Mickey, rogue anthropomorphic broomsticks, and thousands of gallons of water. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice marked the cinematic debut of Mickey Mouse with pupils, as designed by Fred Moore (the dwarfs on Snow White, the mermaids in 1953’s Peter Pan) – Mickey was first drawn with pupils on a program to an infamous, booze-filled party Walt Disney threw in 1938. With pupils, Mickey’s gaze provides a sense of direction that black ovals make ambiguous. The additional personality – not to say Mickey Mouse’s original character design lacked personality – thanks to the pupils strengthens Mickey’s expressions of jollity, shock, submissiveness. A lanky, stern sorcerer is Mickey’s brilliant foil. Their physical differences and reactions imbue The Sorcerer’s Apprentice with a troublemaking charm recalling Mickey’s earliest short films, sans the slapstick that defined those appearances. These decisions heralded a new era for how the Walt Disney Studios’ mascot would be animated and portrayed in his upcoming shorts.

This segment’s chiaroscuro sets a pensive atmosphere, enclosing Mickey in a black and brown gloom as he – a nominal apprentice – is tasked with menial duties, not magic. The indefinite shape of the sorcerer’s chambers owes to German Expressionism (as does the penultimate piece in Fantasia), with its impossibly curved angles and architectural fantasy hiding secrets that no sorcerer’s apprentice assigned to carry buckets of water could understand. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice tonal shifts always feel justified, rooted in the sequence’s character and production design – although, in this regard, the sequence is surpassed later in Fantasia.

Immediately following a mutual congratulations between Mickey (voiced by Disney) and Stokowski is Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Stravinsky’s brief one-act ballet/piece debuted in 1913 to an audience riot because of its musical radicalism – The Rite of Spring liberally partakes in polytonality (using two or more key signatures simultaneously), polyrhythms, constant meter changes, unorthodox accenting of offbeats, chromaticism, and piercing dissonance. Concert hall attendees had heard nothing like The Rite of Spring before and, even in 1940, Stravinsky’s composition divided audiences. The Rite of Spring – precipitating the concert hall’s philosophical battles of the late twentieth and twenty-first century over whether melody and coherent rhythm still has a role to play in contemporary classical music – is a gutsy choice to present to general audiences.

At fifty-eight years old when Fantasia was released, the Russian-born, French-naturalized (and soon-to-be American citizen) Stravinsky is the only composer to have lived to see one of his pieces adapted for a Fantasia movie. Stravinsky despised Stokowski’s interpretation and cutting of his music (all musical cuts were Stokowski’s decisions, reasoning that an audience of classical music neophytes might not be comfortable in a theater for too long during Fantasia), but applauded the animated interpretation of his work. As a ballet, The Rite of Spring is about primitivism. The Disney animators sheared the piece of its human element to liberate themselves from the ballet’s narrative (and believers of creationism). Instead of portraying primitive humans, they elected to depict an account of Earth’s early natural history – its primeval violence, the beginning of life, the reign and extinction of the dinosaurs. Astronomer Edwin Hubble, English biologist Julian Huxley, and paleontologist Barnum Brown served as scientific consultants on The Rite of Spring, imparting to the animators the most widely-accepted theories within their respective scientific fields at the time.

As the camera moves towards the young Earth, Stravinsky’s piece clangs with orchestral hits emboldened by the volcanic violence on-screen – the animated flow of the lava and realistic bubble effects (studied by the animators using high-speed photography on oatmeal, mud, and coffee bubbles inflated by air hoses) are technical masterstrokes. Giving way to single-celled organisms and later the dinosaurs, the camera’s perspective keeps low, emphasizing the height of these prehistoric creatures. The suggestion of weight to the dinosaurs distinguish them from comic, cartoonish depictions in American animation up to that point. The Rite of Spring is the only Fantasia segment where I can imagine viewers unversed in classical music, but making an honest attempt to appreciate the music, being repelled for the entire passage because of the music itself. Otherwise, so ends Fantasia’s immaculate first half.

After the intermission, we meet the Soundtrack, a visual representation of the standard optical soundtrack, with Deems Taylor. It is an entertaining diversion before Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 (“The Pastoral Symphony”) – accompanied by scenes of winged horses, centaurs, pans, and gods from classical mythology. These characters and backgrounds, and clear story were intended for Pierné’s Cydalise and the Satyr before its deletion from the program. Seeking a replacement piece, Disney chose Beethoven’s Pastoral over Stokowski’s objections. Stokowski, who largely dismissed potential criticisms from diehard classical music fans and encouraged Walt’s experimentation in their meetings, noted that Symphony No. 6 – the unidentical twin of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5; both were composed simultaneously and debuted to the public on the same evening in 1808 – was Beethoven’s tribute to the Viennese countryside and that, according to Beethoven’s program notes from that 1808 concert, represented, “more an expression of feeling than painting.” Beethoven’s long summer walks amid babbling brooks, verdant forests, and wildlife provided solace from his increasing deafness. Deems Taylor, acknowledging Stokowski’s citations of the symphony’s history, thought the decision a brilliant one. By simple majority, Walt’s repurposed idea for the mythological setting for the Pastoral was produced.

For the entirety of the Pastoral’s second movement, we see cupids assisting in centaur courtship. These hackneyed scenes are glacially paced, overly dependent on Fred Moore’s risqué good girl art. Fantasia’s most objectionable content also appears in the second movement in the form of crude racial caricatures of black women – though the worst example will almost certainly not be in any available modern print of Fantasia, as the Walt Disney Company has consistently cut the footage and essentially denies it ever existed. The story’s tone almost trivializes Beethoven’s Pastoral, making the seond movement a tiresome Silly Symphony. Arguably the weakest of the original Fantasia numbers (Stokowski’s criticisms justified by the final product), the Pastoral nevertheless contains an eye-catching palate of color that makes it unmissable. Encouraged by the supervising animators on the Pastoral to use as much color as possible, the throngs of artists assigned to this were up to the task. Rarely does Technicolor, in full saturation, look brighter than when the young flying horses take to the sky, centaurs and centaurettes partake in mating rituals, and an ever-inebriated Bacchus stumbles into the centaurs’ party.

From the closing ballet of Act III of Amilcare Ponichelli’s opera La Gioconda, the Dance of the Hours is the penultimate piece in Fantasia. Dance of the Hours suffers from its placement in the film. After Bacchus’ simpleminded, jolly antics in the Pastoral, this whole segment is the one that most resembles Disney’s Silly Symphony short films. Presented as a comic ballet with ostriches, elephants, hippopotamuses, and alligators, the Dance of the Hours has the ideal supervising animators assigned to it – caricaturist “T.” (Thornton) Hee and Pluto/Big Bad Wolf animator Norm Ferguson. Dancer Marge Champion (the model for Snow White’s dancing), ballerina Tatiana Riabouchinska and her husband David Lichine served as models for the balletic motions, endowing the segment with choreographic – though perhaps not biological – accuracy. As long as the viewer basks in the Dance of the Hours’ unadulterated silliness and does not mind the fact it is the least innovative piece in terms of its animation, it is an enjoyable several minutes of Fantasia.

Fantasia concludes with a staggering pairing: Modest Mussorgsky’s‡ tone poem Night on Bald Mountain (partial cuts) and Franz Schubert’s Ave Maria (with English lyrics). After an inconsistent second half to Fantasia, the film ends with two selections so remarkably contrasting in musical form and texture and animation. Night on Bald Mountain, like Dance of the Hours, is the responsibility of an ideal supervising animator in Wilfred Jackson (1937’s The Old Mill, Alice in Wonderland) and one of the finest character animators in Bill Tytla (Stromboli in Pinocchio, Dumbo in Dumbo). Using Mussorgsky’s written descriptions for the piece, the animators closely adhere to the composer’s imagined narrative. On Walpurgisnacht, a towering demon atop a mountain unfurls his wings and summons an infernal procession from the earthly and watery graves below. This demon, the Slavic deity Chernabog, is Tytla’s greatest triumph as a character animator and for all animated cinema. With movements modeled by Béla Lugosi of Dracula (1931) fame – one could not ask for a better model – and Jackson himself, Tytla captures Chernabog’s enormity, the torso’s muscular details, and graceful arm and hand movements that never falter frame-by-frame. Chernabog moves more realistically than any Disney character – in shorts and features, Rotoscoped or not – and would retain that distinction until the advent of computerized animation. In Tytla’s mastery, one forgets that Chernabog is nothing but dark paints.

Jackson’s use of contrasting styles to demarcate Chernabog from the ghosts and spirits summoned to the mountain’s summit further contributes to Night on Bald Mountain’s satanic atmosphere. The shades answering Chernabog’s call appear as either rough white pencil sketches that one might expect in a concept drawing or translucent, wavy figures animated with rippling effects that required a curved tin to complete. That rippling, wafting effect – lasting only several seconds in Night on Bald Mountain – was among the most labor-intensive parts of Fantasia, requiring animators to be present at work in multiple shifts across twenty-four hours to photograph the movements for each frame. The Walt Disney Animation Studios would not delve into such darkness again until The Black Cauldron (1985).

Night on Bald Mountain benefits from being followed immediately – without a Deems Taylor introduction (he introduces both pieces prior to the Mussorgsky) – by Schubert’s Ave Maria, and vice versa. As Chernabog and the spirits romp, an Angelus bell tolls just before the dawn, signalling the end of their nocturnal merriment. Stokowski arranged Night on Bald Mountain’s final bars to fade away as a vocalizing chorus precedes the beginning of the Ave Maria. Where Night on Bald Mountain incorporated numerous styles in a disorderly frolic, the Ave Maria is rigid and structured by design (the camera only moves horizontally from left to right or zooms forward). In twos, robed monks walk through a forest bearing torches – their figures obscured behind trees, their reflections gleaming in the water. As the camera zooms forward for the first time, darkness envelops the screen. Using English lyrics by Rachel Field that do not adapt Schubert’s German lyrics, soprano Julietta Novis sings the final stanza of the Ave Maria (Field’s first two stanzas were unused) as the multiplane camera gradually glides through a still bower. The Ave Maria features some of the smallest individually-animated pieces (the monks) ever brought to screen. And with the multiplane camera (when the monks are onscreen, the multiplane camera – which was created to provide depth to animated backgrounds – is utilized, for the first time in its existence, to evoke flatness), it also contains what may be the longest uncut sequence in animation history.

The Ave Maria’s beauty sharpens the contrast between itself and Night on Bald Mountain – the sacred and the profane. Their spiritual and musical pairing is cinematic transcendence. Yet, the Ave Maria was almost cut entirely from the film at the last moment, as it was spliced into the final cut four hours before Fantasia’s world premiere – all thanks to an earthquake that struck Southern California a few days earlier. How fortunate for those worked on the segment, the preceding Night on Bald Mountain, for Fantasia, and cinema that the Ave Maria was included in the end.

Some of the pieces considered by Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor that did not make the final cut appeared in Fantasia 2000 – most notably Igor Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite (1919 version), which Walt initially preferred over The Rite of Spring until convinced by Taylor otherwise. In contrast to his company’s contemporary attitude, Walt Disney himself was disapproving towards proposing sequels, with Fantasia proving the only exception. Walt imagined sequels to Fantasia to be released every several years, with newer Fantasia sequences starring alongside one or two reruns. Other pieces Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor (who wrote additional introductions in anticipation of future Fantasia films; I am looking into whether these introductions still exist) contemplated remain unadapted as Fantasia segments. The notes and preliminary sketches of some of these proposed segments – including a fascinating consideration to adapt selections from Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen (the Ring cycle) to J.R.R. Tolkien’s then-newly-published children’s book The Hobbit – most likely reside in the Walt Disney Archives for reference if and when the company’s executives approve a third Fantasia movie.

Walt Disney’s dream of Fantasia sequels was quickly dashed. His proposal to add Fantasound – the studio’s prototypical variant of a stereo sound system – proved extravagantly expensive for all but a dozen movie theaters in the United States. Released as a roadshow (a limited national tour of major American cities followed by a general release), the inflated ticket prices due to the roadshow’s Fantasound system harmed Fantasia’s box office. Though a vast majority of film critics and some within classical music circles hailed Fantasia, the vocal and vehement division was inescapable. Some cultural and film critics, citing solely that Walt Disney had bothered to touch classical music, castigated Walt and Fantasia as pretentious (classical music’s negative reputation of being dated, inaccessible, and snobby was not nearly as widespread in the 1940s as it is today; musical appreciation and education has receded in the U.S. in the last several decades). Intransigent classical music purists – usually noting Stokowski’s frequent cutting of the music – lambasted Fantasia as debasing the compositions (I dislike Stokowski’s cutting, certain stretches of the Bach and Stravinsky recordings, and much of the Pastoral’s story, but this is a reactionary overreach). The negativity from both spheres stole the headlines, eroding interest from North American audiences. With the European box office non-existent, Pinocchio and Fantasia stood no chance of turning a profit on their initial releases. Their combined commercial failure sent the studio in a financial tailspin – a crisis that a comparatively low-budget Dumbo single-handedly averted.

Rankled by the criticism directed towards Fantasia, Walt Disney’s anger turned inwards, fostering a personal and corporate disdain of intellectuals that marked the rest of his career. One sees it in his irritation towards critics decrying the handling of race in Song of the South (1946); it is also there in his dismissive treatment of P.L. Travers over an adaptation of her novel Mary Poppins.

Mounting tension among Disney’s animators over credits, favoritism towards veteran animators over the studio’s pay scale and workplace amenities, the announcement of future layoffs due to the studio’s financial crisis, the unionization of animators at all of Disney’s rival studios, and Walt’s political naïveté in heeding the words of Gunther Lessing (the studio’s anti-communist legal counsel) threatened to explode into public view. On May 28, 1941, unionized Disney animators began what is known – and downplayed to this day by the Walt Disney Company – as the Disney animators’ strike. The strike, which lasted for two months, shredded friendships between strikers and non-strikers. Walt Disney, who surveyed the striking animators and filed away names in his deep memory, is said to have repeatedly referred to the strikers as, “commie sons of bitches”. More than once at the studio’s entrance, Walt slammed on his car’s accelerator towards the strikers and hit the brakes before making contact.

Under pressure from lenders, Walt recognized the union in late July but nevertheless fired numerous striking (and non-striking) animators in the months afterwards. Many of those terminated by Disney joined cross-Hollywood rivals or founded the upstart United Productions of America (UPA; Mr. Magoo series, 1962’s Gay Purr-ee). An embittered Walt would never again feel the sense of family among his studio’s staff as he did in the 1920s and ‘30s at the Hyperion studio, despite his public persona and statements to the contrary.

A wonder of filmmaking, Fantasia arrived in movie theaters as Disney’s Golden Age began to fracture. If not for war or Walt Disney’s obstinance, this era might have lasted longer. In the decades since, the contemptuous responses to Fantasia from classical music elites have cooled – for classical music lovers with not nearly as much institutional power, Fantasia has indeed become a beloved gateway into the genre. Its irrepressible beauty, invention, and bravery as a visual concert cannot be overstated.

My rating: 10/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating.

This is the sixteenth Movie Odyssey Retrospective. Movie Odyssey Retrospectives are reviews on films I had seen in their entirety before this blog’s creation or films I failed to give a full-length write-up to following the blog’s creation. Previous Retrospectives include The Wizard of Oz (1939), Dumbo (1941), and Godzilla (1954).

For more of my reviews, check out the “My Movie Odyssey” tag on my blog.

* The completed Clair de Lune segment was re-edited and integrated into Make Mine Music (1946).

‡ Mussorgsky’s original score for Night on Bald Mountain – which was not performed again during his lifetime following the piece’s premiere – went missing after his death in 1881. In 1886, fellow composer and colleague Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, controversially began editing Mussorgsky’s partially missing scores using his “musical conscience” (including the opera Boris Godunov). Rimsky-Korsakov wanted to preserve and retain his colleague’s music among aficionados of Russian classical music. The version of Night on Bald Mountain heard in Fantasia is Rimsky-Korsakov’s arrangement of the piece. Mussorgsky’s original score to Night on Bald Mountain was found in 1968, but the Rimsky-Korsakov arrangement is more frequently performed today.

#Fantasia#Walt Disney#Leopold Stokowski#Deems Taylor#Mickey Mouse#Philadelphia Orchestra#Joe Grant#Dick Huemer#James Wong Howe#Fred Moore#T. Hee#Norm Ferguson#Wilfred Jackson#Bill Tytla#My Movie Odyssey

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Baby mine, don't you cry.

Baby mine, dry your eyes.

Rest your head close to my heart,

Never to part, baby of mine."

― Baby mine, Dumbo (1941)

#Dumbo#Baby mine#Disney#Helen Aberson#Harold Pearl#Ben Sharpsteen#Otto Englander#Joe Grant#Dick Huemer

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

DUMBO (Dir: Ben Sharpsteen, 1941).

Walt Disney’s 4th animated feature is the story of the circus elephant born with oversized ears who uses his disadvantage to his advantage when he discovers his ears enable him to fly.

At 64 minutes it is one of the shortest Disney movies but is a masterclass in storytelling. Not a second of screen time is wasted; in fact its tight narrative and snappy pace make it an advocate for shorter movies!

It is also the most emotionally moving Disney feature. Many a tear has formed in audiences eyes as Dumbo is separated from his mother and ostracised by the other elephants. It is a credit to writers Joe Grant and Dick Huemer that the emotion never descends into false sentiment and there is also much humour to offset the heartache.

The animation too is exemplary, as one incredible animation set piece follows another. Highlights include the shadowy roustabout sequence, the tragicomic disastrous pachyderm pyramid, Dumbo’s inaugural flight and best of all the surrealist Pink Elephants On Parade. The character animation, opting for a more ‘cartoony’ look than in previous features, is also among the studios best as are the beautiful watercolour backgrounds against which the action takes place.

Add to this a fantastic score by Frank Churchill and Oliver Wallace, including the tender Baby Mine and the clever wordplay of When I See An Elephant Fly, and a powerful message of acceptance and the result is one of the greatest movies, animated or otherwise, of all time. In my opinion only rivalled for greatness by Walt Disney’s Pinocchio (B Sharpsteen & Hamilton Luske, 1940). Dumbo is unarguably a masterpiece and a work of art.

For more reviews of vintage Disney classics check out my blog JINGLE BONES MOVIE TIME at the link below!

#dumbo#walt disney#ben sharpsteen#joe grant#dick huemer#frank churchill#oliver wallace#pinocchio#disney#disney animation#walt disney animation studios#disney classics#animation#animated movies#hollywood#vintage hollywood#golden age hollywood#classic hollywood#movie review#movie reviews#every movie i watch 2019

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

#fantasia vhs#fantasia#1940#walt disney#animated film#walt disney productions#joe grant#dick huemer#ben sharpsteen#disney animated feature film#rko radio pictures#mickey mouse#disneyland#vhs#vhs tapes#vhs art#vhs positive#retro#retro wave#vintage#vintage wave#40s#1940s#1940s movies#1940s films

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Dumbo | Official Trailer 🐘🎪

He’s so cute!! 😍🤗

#dumbo#dumbo 2019#colin farrell#michael keaton#danny devito#eva green#alan arkin#nico parker#finley hobbins#deobia oparei#joseph gatt#sharon rooney#tim burton#otto englander#joe grant#dick huemer#helen aberson#harold pearl#walt disney

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Sassy Cats” (1933)

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

Season 7; Episode 326 - ANTHOLOGIES: Fantasia (1940)/Fantasia 2000 (1999)

Fantasia 1940 American animated musical anthology film produced and released by Walt Disney Productions, with story direction by Joe Grant and Dick Huemer and production supervision by Walt Disney and Ben Sharpsteen. The third Disney animated feature film, it consists of eight animated segments set to pieces of classical music conducted by Leopold Stokowski, seven of which are performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra. Music critic and composer Deems Taylor acts as the film's Master of Ceremonies who introduces each segment in live action.

Fantasia 2000 1999 American animated musical anthology film produced by Walt Disney Feature Animation and released by Walt Disney Pictures. Produced by Roy E. Disney and Donald W. Ernst, it is the 38th Disney animated feature film and sequel to 1940's Fantasia. Like its predecessor, Fantasia 2000 consists of animated segments set to pieces of classical music. Celebrities including Steve Martin, Itzhak Perlman, Quincy Jones, Bette Midler, James...

0 notes