#Imperial Sourcebook

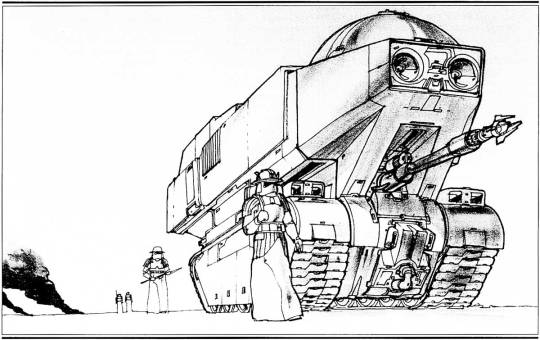

Photo

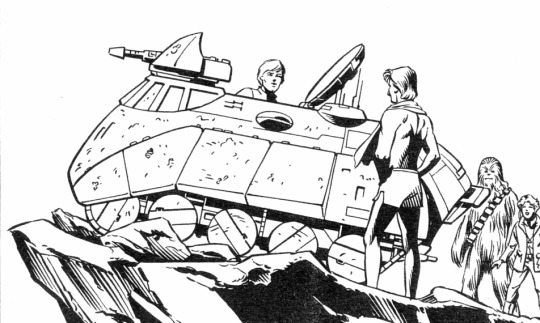

A heavy recovery vehicle attached to Hell’s Hammers, an elite armor unit of the Empire (Joe Johnston concept art for what became the AT-AT in The Empire Strikes Back, from the Imperial Sourcebook for Star Wars the Roleplaying Game by Greg Gordon, West End Games, 1989) WEG’s writers used previously unseen art from the files of Lucasfilm, Ltd, as the basis of many new additions to the Star Wars expanded universe. Hell’s Hammers are mentioned again in Imperial Entanglements (1996) in a scenario for Star Wars Miniatures Battles featuring a recovery crew on foot attempting to retrieve an immobilized repulsortank.

#Star Wars#Joe Johnston#Star Wars D6#Star Wars RPG#Star Wars the Roleplaying Game#Imperial Sourcebook#Star Wars concept art#sci fi#Star Wars Expanded Universe#SWEU#The Empire Strikes Back#ESB#Hoth#stormtrooper#snowtroopers#Hell's Hammers#Star Wars Miniatures Battles#West End Games#WEG#Lucasfilm#tank#recovery vehicle#heavy recovery vehicle

250 notes

·

View notes

Text

reading through the order of battle section in the imperial sourcebook and i just know someone had a great time listing out each formation's crew, equipment, and support personnel down to the last head and rivet

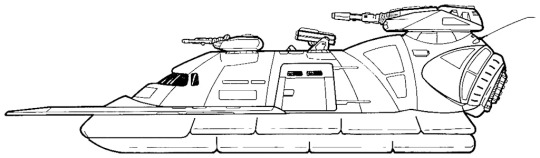

its a shame they don't seem to have talked to any the people who wrote the equipment section, because none of these match up in the slightest. what is a "light transport vehicle"? it's described as being served by a crew of 4: a mechanic, a driver, a sensor officer, and a gunner. there are no vehicles in the vehicle section of the book that match that description.

the hoverscout comes close, but it has three gunners (fun fact: this thing is actually a bonafide air-cushion hovercraft, not a repulsorlift vehicle. not really relevant, but it's neat)

the chariot LAV crews 3 which makes sense if the mechanic stays back at base, except for the fact that it's explicitly described as being modified as a command vehicle

the best guess i have is that its basically a less-armored version of the LAV

this means that if i want my players to encounter a repulsorlift squad, then i have to either just use the lav stats, or brew up something myself

that said the imperial sourcebook is amazing highly recommend for anyone who wants a 133-page infodump on every detail of the imperial military, intelligence, and governance apparatus

0 notes

Photo

Imperial Sourcebook

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

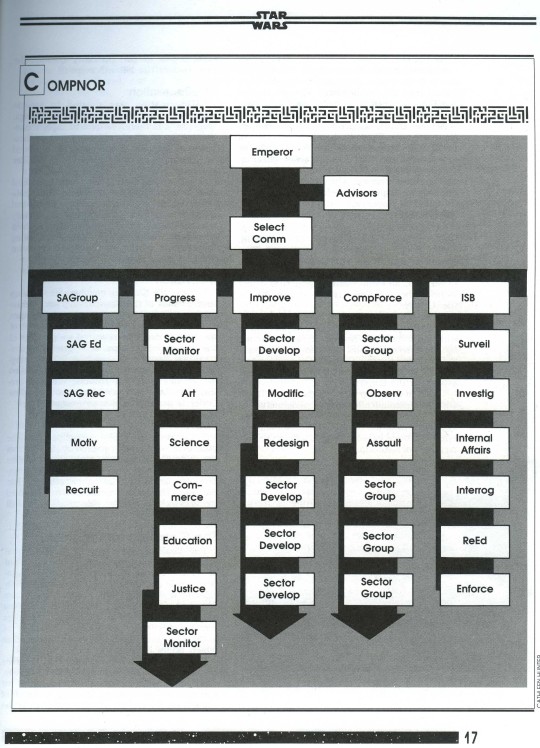

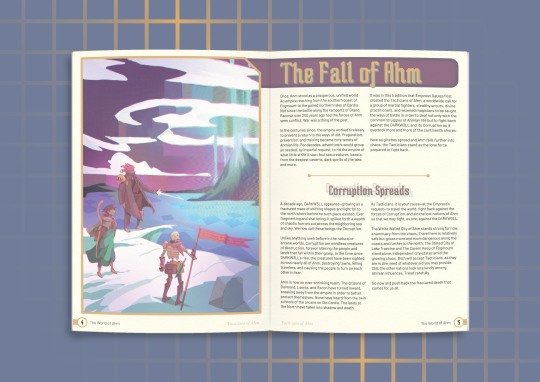

Pages on COMPNOR and The ISB scanned from the 1989 Imperial Sourcebook. Click on the images and zoom in to read.

These might be useful to anyone wanting to write fic about imperials/ISB characters or is just interested in the lore. I have the whole sourcebook, so if there’s anything else you’d like me to share just let me know!

#Star Wars#the imperial sourcebook#COMPNOR#The ISB#The Imperial Security Bureau#the galactic empire#Emperor Palpatine#Dedra Meero#scan

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

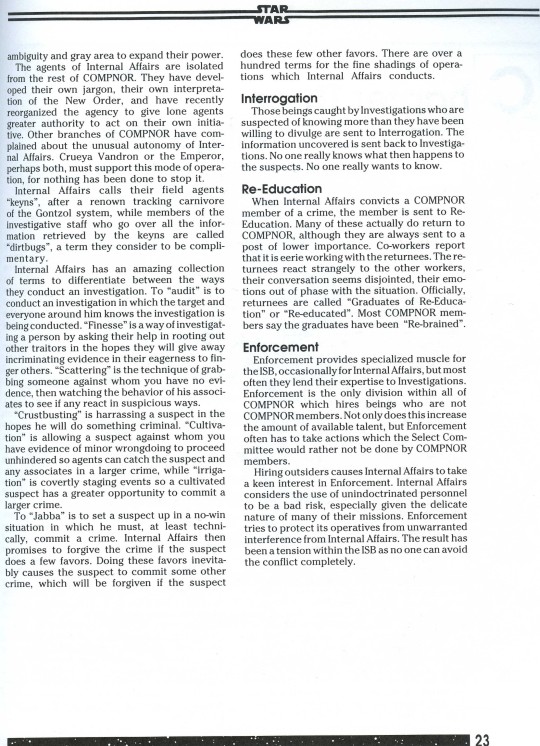

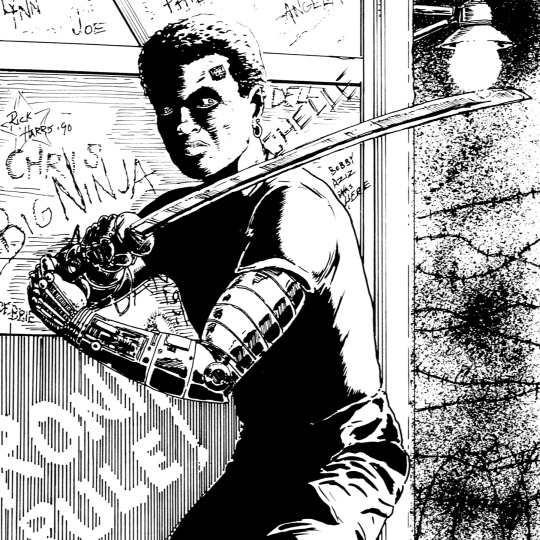

Rotten to the Core (1990) is the last 2300AD supplement. It is primarily a sourcebook detailing Libreville, the city in Gabon, Africa (in 2300, part of the French empire) where the space elevator, amusingly referred to as the “Beanstalk” is anchored. Naturally, this sort of aperture to the stars is going to encourage a lot of power, money and corruption, making it an excellent venue for cyberpunk. I will say, despite a lot of reasonably realistic things going on in this book, it is weirdly white for a city in Africa, even allowing for the colonial imperialism of the French empire and the probable riptide-like currents of gentrification that would beset a place like Libreville.

Anyway, if you take your expectations for a cyberpunk city, dial all the tech to “plausible” and make sure to check every box established by the sub-genre (including having Tim Bradstreet do some art for you), then you’ll pretty much have Libreville. It is kind of weird having something so early in cyberpunk’s lifespan also be so by the numbers, but there you have it. And that isn’t a bad thing! It is just…an obvious thing. Rotten to the Core is not subtle.

The included adventure may as well be a short story by Billiam Hibson. There’s corporate secrets, dark doings, stolen tech, betrayal, violence, all wrapped in that chrome package. There’s a guy named Steel Cowboy. It’s not high art, but it probably makes a good adventure, honestly — the best RPG adventures tend to be somewhat derivative, right? Where players sort of see the big beats coming. That’s this. And since the cyberpunk aspect in 2300AD is so generic, you can pull it out and run it for anything.

Nice Aulisio cover, it’s got atmosphere.

#tabletop rpg#roleplaying game#dungeons & dragons#rpg#d&d#ttrpg#Traveller#Game Designers Workshop#GDW#2300AD#Cyberpunk#Rotten to the Core

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

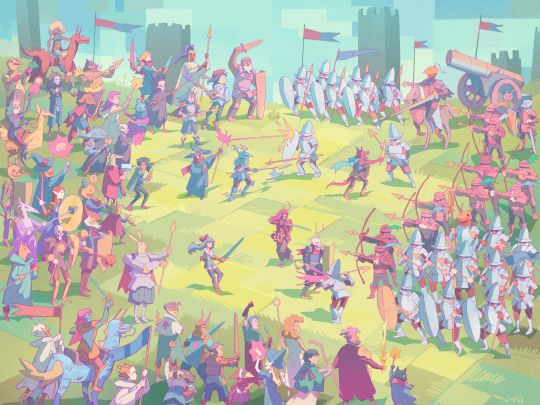

Tacticians of Ahm - Monthly Update #2!

Full spread art by @helenacore depicting Early Graduation's opening field exercises!

Greetings Tacticians!

Tactician of Ahm's Monthly Update #2 is finally here! With it comes the early access version of the setting book, The Ahmian Almanac, which features its first sample region of Ahm, showcasing the style and structure of setting book I am hoping to create with the Almanac. The book will feature lore and locations, of course, but it will also feature more in-depth maps, new NPCs, unique equipment, a complete new Class, and more! I want to create a book that it as much a sourcebook chock full of new things for GMs to bring to the table as it is information about the world of Ahm and inspiration for adventures.

Thanks you so much for the continued support of and engagement with the game! I used more of the raised funds to commission more art from Helena Santana including a new, full-spread art piece for Early Graduation (at the top of the post) and a piece of Dekkin Von Lopesbane character art (also for Early Graduation). Plus, I've worked with Jean Verne on a second preview spread (see above) of our planned look and feel for the game's final layout, this time utilizing some of Helena's awesome art from Monthly Update #1!

Because of my delay of this update (it was originally slated for last month) and the update overall being smaller than I originally was hoping, I am delaying this month's price hike on the game so if you enjoy Tacticians of Ahm now is still a great time to get on board! Tell your friends to do the same! Next update, the price will rise by $5 USD and that will continue apace (barring unforeseen delays like the one I suffered this last month, of course).

Lastly, I recently ran the opening two hours of Early Graduation over on The Weekly Scroll. Check it out if you'd like to see the game in action and see how I run it as the GM!

youtube

PATCH NOTES - v0.8.3

Tactician’s Textbook

Clarified Conditions to apply until the end of target’s next Turn (as opposed to confusing wording regarding Rounds).

Renamed “Shield” Condition to “Ward” to avoid having the same name as a shield, the piece of equipment and updated relevant uses throughout the text.

Ward condition now explicitly blocks all damage AND any/all Conditions while in effect.

Updated Mage Ability - Barrier to include “May be cast on self (1 target maximum per use)”

Added clarifying text to Shields in Equipment section: “(does not block Conditions)”

Added clarifying text regarding applying multiple Conditions to a single target: “A target may suffer one or more different Conditions at the same time. If a target currently has a Condition, they may not be affected by that same Condition again (nor does it add turns of effect to the current Condition) until the current instance has ended.”

Gamemaster’s Guidebook

Added Boar (EL1) to Bestiary

EARLY GRADUATION

Added a massive new piece of art from Helena Santana to the title page, depicting the Tacticians sparring with Imperial Army soldiers during the Field Day exercises!

Added Boar (EL1) to “BATTLE: Wolves in the Woods” and adjusted combatant numbers at various party sizes to more accurately reflect typical intended difficulty.

AHMIAN ALMANAC (NEW!)

Lake Traecine region added, includes the following:

5 Major Points of Interest: New locations for your Tacticians to travel to and explore!

20 Calls for Aid: Adventure hooks and strange happenings across the region!

1 Class: New classes, accessible only to Tacticians who prove their worth!

11 Abilities: New combat skills, taught to those favored by a certain faction!

2 Enemies: New combatants, unique to the specific region or faction!

2 Relics: New guarded/lost pieces of equipment, be they mundane, magical, or corrupt3d!

2 Factions: New groups, wielding political, cultural, or magical power!

1 Shop: A New specialty establishment carrying new and rare items!

4 Characters: New NPCs for your Tacticians to meet, interact with, and fight alongside!

More detailed (placeholder) map of the region with travel paths!

#ttrpg#indie ttrpg#ttrpgs#rpg#fantasy#tactics#final fantasy tactics#tacticians of ahm#grid combat#combat#dnd#jrpg#Youtube

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Editor's Note from The Black Sands of Socorro by Patricia A. Jackson

While researching Patricia A. Jackson’s entire body of Star Wars work for a short story anthology, I came across the West End Games sourcebook Star Wars: The Black Sands of Socorro (1997.) It’s a crucial work of Star Wars ephemera: The first creator of color writing for Star Wars in an official capacity, writing not just about individual characters of color, but centering entire cultures populated by non-white characters. A young Black woman in the 1990s wrote science fiction for Star Wars, worldbuilding with concepts like antislavery, indigeneity, linguistic divergence, and settler colonialism...while Disney-Lucasfilm in the 2020s ineffectually positions Star Wars as a post-racial fantasy.

I non-hyperbolically refer to Patricia A. Jackson as the “Octavia Butler of Star Wars,” not because fans of color need to be officially sanctioned by Lucasfilm to create Star Wars content, but because of how difficult it is to carve out anti-racist space in a transmedia storytelling empire. Challenging even in transformational fandom spaces (e.g. fan works), to broach race in affirmational fandom spaces—or while writing content for the property holder—is to be unflinchingly subversive.

And Jackson did it first. In an interview with Rob Wolf in 2022, Jackson described her experience writing race into Star Wars in the 1990s as an “experiment.” The planet, peoples, and cultures of Socorro were a way for Jackson to obliquely, yet concretely, center Blackness and racial justice into Star Wars, pushing the racial allegory constrained by the original trilogy to its limits.

Since it’s inception, Star Wars has spent much of it’s storytelling on the fringes of the galaxy (whether it’s Tatooine or Jakku, Nevarro or Ajan Kloss.) The Black Sands of Socorro is an extension of that trope, but where the Star Wars films used indigeneity as set dressing (eg. “Sand People”, Ewoks, Gungans, etc.) Jackson creates a vivid world where indigenous culture and settler colonists collide; where characters are coded with dark skin and central to the action. The planet Socorro is distinct as a Star Wars setting. As one of the only places in the galaxy where slavery is eradicated with a vengeance, Socorro refuses to let go of a plot line Star Wars media often leaves behind. Socorro is a haven from Imperial fascism, a space where readers are invited to imagine a story that does not center around occupation.

When I learned that Patricia A. Jackson no longer has a physical copy of The Black Sands of Socorro, I realized that I had the materials and the means to create a fanbound hard copy for her home library (well, and also for my own home library.) While this handmade book is not an exact reproduction of the RPG supplement, I hope my renvisioning of the supplement as an in-universe travel guide lives up to the original work.

As the idea of creating a travel guidebook based on the original material percolated, I reflected on the State of Race in Star Wars in the year since I compiled Designs of Fate, an anthology of my favorite Patricia A. Jackson short stories. In May 2022, actress Moses Ingram debuted as Inquisitor Reva Sevander, the deuteragonist in the Dinsey+ streaming Obi-Wan Kenobi series. As predicted by Lucasfilm—and any fan sick of alt-right Star Wars related “whitelash”—Ingram was promptly subjected to a firehose of racialized harassment and misogynoir.

Yep, fascist self-proclaimed fanboys complained about a Black woman Inquisitor in 2022, having no idea (or deliberately whitewashing) that one of creators of the entire freakin’ concept of Inquisitors was a Black woman writing for the Star Wars Adventure Journal three decades ago.

Then, a public facing Star Wars account (@StarWars on Twitter) broke precedent and slapped back at the trolls. Lead actor Ewan McGregor filmed a video retort, posted on @StarWars, stating “racism has no place in this world” and telling off the racist bullies: “you’re no Star Wars fan in my mind.” A few months later, Disney+ debuted it’s second flagship Star Wars streaming series of the year, starring a Latino actor as the protagonist. In the opening episode of Andor, a police chief describes Diego Luna’s eponymous lead as a “dark-featured human,” perhaps the closest the franchise has ever gotten to acknowledging out-of-universe constructions of race, to date. The series explored aspects of imperialism with more depth than Star Wars had previously done on screen, such as the Empire’s treatment of the native people of Aldhani. And, in November, the The Acolyte, a Disney+ series co-developed by Rayne Roberts, announced Amandla Stenberg and Korean actor Lee Jung-jae as its top-billed leads. Stenberg will be the first Gen Z, mixed race, Black, Inuit, queer, and non-binary actor to lead a major Star Wars series.

On the Patricia A. Jackson Star Wars front, in 2022, Jackson’s character Fable Astin was an easter egg in the Obi-Wan Kenobi series. Jackson will again write for Star Wars in an official capacity in From a Certain Point of View: Return of the Jedi, due for publication in Fall 2023. A series about Lando Calrissian, the galaxy’s most famous Socorran, is still in production, so I have my fingers crossed that we may soon see Socorro on camera.

I wonder if this past year will have been a fulcrum year for BIPOC fandom. Maybe Disney has finally realized it’s bad for business that the alt-right uses social media algorithms and Star Wars fan spaces as a soft recruiting ground to radicalize young white men? Maybe Star Wars as a franchise will continue to loudly disavow fan whitelash and firmly position performers of color in true leading roles? I really hope so. On the other hand, as much as I am in favor of increased representation in Star Wars storytelling, I am also troubled by Disney-Lucasfilm’s framing of the Galaxy Far, Far Away (GFFA) as “colorblind.” Recently, Star Wars fans have been asked to accept that in the (a long time ago) sci-fi futurepast GFFA, humans have always been post-racial, and it’s just a coincidence that racialized people were not caught on camera the way white characters have been for years. The galaxy is post-racial and it’s just acoincidence that the movers and shakers of the galaxy have largely been depicted as white men for the past 40 years of media.

For example, in the decade since Disney rebooted the expanded universe, fans have learned that Star Wars’s biggest galactic war criminal to never be depicted on screen is Admiral Rae Sloane, a bisexual Black woman who was the leader of Imperial remnant forces, one of the architects of the First Order, and personal mentor to General Hux. Under Disney-Lucasfilm’s post-racial retcon of the Star Wars universe, the allegorical fascists are intersectional equal opportunity employers (at least in expanded universe content like animation, video games, and novels.) Along those lines, several of the franchise’s newly introduced, prominent women of color have been part of the Empire: Imperial loyalist Cienna Ree (Lost Stars), Inferno Squad leader Iden Versio (Star Wars: Battlefront II) former stormtrooper Jannah (Episode IX), First Order pilot Tamara Ryvora (Star Wars: Resistance), Inquisitor Trilla Sundari (Jedi: Fallen Order), Captain Terisa Kerrill (Star Wars: Squadron) and, most recently, Inquisitor Reva Sevander. Once the sole purview of stodgy, very white and very British men (demonstrably so even in the sequel trilogy movies,) now anyone can be a stooge of the Empire.

That’s not to say that marginalized people can’t collude with fascism, or that there haven’t been heroic characters of color introduced in recent years. Rather, I posit that in order to sell audiences on the post-racial/colorblind GFFA, fascist-of-color characters like Rae Sloane or Giancarlo Esposito’s Moff Gideon (The Mandalorian) are created by necessity. The franchise wants to at once be racially inclusive and yet never directly address race. In Star Wars, real world oppression is primarily explored through allegory—such as Solo (2018)’s bit on droid rights, the clone army, or the myriad of non-human alien bodies that nonetheless are coded with racial stereotypes. A lot has been said about how allegory in sci-fi allows audiences to grapple with inequality from a comfortable distance, and not enough has been said about which audience is being prioritized for comfort.

What does it mean when race is supposedly a non-issue for humans in the GFFA, but creators and actors with marginalized identities cannot participate in Star Wars in any capacity without experiencing identity-targeted harassment? In the past ten years, this has been true even for white women like Kathleen Kennedy and Daisy Ridley, but the vitriol has been most strongly directed towards Black women like Lucasfilm Story Group lead Kiri Hart, author Justina Ireland and The High Republic Show host Krystina Arielle. Can the Galaxy Far, Far Away truly be “colorblind” or “post-racial” (never-racial?) if the narrative continually centers white characters and replicates all the common racial inequities seen in commercialized Hollywood storytelling? Upon the release of The Force Awakens in 2015, critic Andre Seewood aptly described Finn’s positioning in the story as “hyper-tokenism,” even presciently predicting that Finn would continue to be hyper-tokenized in Episodes VIII and IX. As the narrative veered away from Finn, it also left unrealized a stormtrooper rebellion plot line where Finn could have been, in effect, a Black abolitionist. Actor John Boyega’s critique of his experience in the sequel trilogy aligns with Seewald’s assessment: “Do not bring out a Black character, market them to be much more important to the franchise than they are and then have them pushed to the side.”

Published in 1997, The Black Sands of Socorro came before Finn, before Mace Windu, back when all the melanin of Star Wars could be found in Billy Dee Williams’s singular swagger and James Earl Jones’s distinctive voice. Back then, the most prominent Black actress in the original trilogy was dancer Femi Taylor, who played Oola, the hypersexualized green twi’lek fed to the rancor in Return of the Jedi. Bantam Spectra, the publisher that held the license for Star Wars from 1991 to 1999, had no leading characters of color in its’ Expanded Universe. The first full length Star Wars novel by a writer of color, Steven Barnes’s The Cestus Deception15, would not be published until 2004. Even though the book featured two protagonists of color, they would not be depicted on the cover. At Comic-Con in 2010, I spoke with Tom Taylor, a white Australian comic book writer who tried to make the lead family in Star Wars: Invasion (2009) a Black one, but was shut down during the creative process. The comic instead depicts a family of blondes, because the publishers did not think fans would embrace leads of color. All this to say, the inclusion of melanated characters in Star Wars has been so, so hard fought. It’s incredible The Black Sands of Socorro exists at all. It’s more than worthy of celebration, and I’m floored that more attention has not been brought to it.

Patricia A. Jackson is a smuggler.

This sourcebook was explicitly written to assist fans in telling their own Star Wars stories, and in it Patricia A. Jackson smuggled in emphatic allusions to the Black Panther movement and the trans-Atlantic slave trade, smuggled in commentary on indigeneity and settler colonialism, and smuggled in multiple ways for fans to envision characters of color. Her writing has consistently added richness to the GFFA, and in The Black Sands of Socorro she envisions multiple histories for multiple cultures coded as non-white. She ensured the existence of not mere tokens, but flourishing societies of people of color in Star Wars.

The coda for The Last Jedi again shows how perilously close to tokenization characters of color, particularly Black characters, are in modern day Star Wars. In this film, the franchise returns to itsprevious exploration of slavery with the depiction of enslaved children on Canto Bight. The last speaking lines of the film are from Oniho Zaya (played by Josiah Oniha, a young Black British actor) who recounts Luke Skywalker’s heroic exploits to the other children. The film then closes out by showing that one of the downtrodden children is Force-sensitive—a future hero in the Star Wars mythos. In a film where every single Force-user depicted is white, the next generation kid with the potential is, again, a young white boy. Once again, the Black character can only serve the narrative in a supporting role. A franchise depicting a colorblind fantasy continually reifies racial and gender hierarchies in America. With The Acolyte, scheduled for release in 2024, it’s possible the franchise may finally be shifting past hyper-tokenism. In the meantime, fans of color and our erstwhile allies will continue doodling in the margins.

In the end, the sequel trilogy left the Canto Bight plot line (and the overarching slavery plot line started in Episode I) unresolved. I’d like to think the Black Bha’lir strafed Canto Bight and grabbed those kids. It seems like something they would do. Out among the stars, Oniho Zaya is adventuring with Drake Paulsen, and his story does not bracket another characters’; he is central. The Black Sands of Socorro is a launching pad for stories like that. It represents how fans of color have always carved out pieces of Star Wars for ourselves.

#socorro#star wars legends#swrepmatters#star wars adventure journal#star wars d6#patricia a. jackson#fanbinding#binders note

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you ever read the Black Crusade sourcebooks? They do a very good job of showcasing interesting non-imperial/chaos-aligned human societies in the 40k setting.

I haven't, actually! All the Dark Heresy and Rogue Trader lore, absolutely, but none of the rest of the FFG lines.

(In much the same way that star wars is better when the sith and jedi are barely ever mentioned, I adored the cults and xenos books specifically because they all had a bunch of interesting weirdness mostly unique to the games' specific settings, and when a alien race or demon/god from the main franchise got mentioned they felt big and terrifying)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Yawning Boredom Of The Word Epic

Good god this is a dull word, right?

Cancon was a fun convention, I liked it a lot. But while I was there, I saw this word being worn into a groove in my brain. It was an all-purpose descriptor, a vague and generic positivity, a detailer of scope and an encouragement for engaging, and every time I saw it I felt a bit of my brain shut down in response. I think some of this is just the normal overuse of meaningless words. If someone described a game as being ‘lit’ I would probably also just as much immediately ignore that descriptor. Packing peanut language, that kind of thing.

And I know it’s rich, coming from me to complain about overuse of cliche. I just said ‘packing peanuts’ which is something I am very selfconscious about saying a lot.

It’s not just the ungoogleable game Epic by Wise ‘Maybe We Don’t Want To Be Called White Wizards Any More’ Wizards. It’s also games like Epic Spell Wars of the Battle Wizards: Duel at Mt Skullzfyre or Epic Resort or Tiny Epic and their franchise of genuinely exciting little games, or Crafting Epic Dungeons or Epic Scenery or Epicness Incarnate or Warhammer Epic or Epic Confrontation and you might not know if I made any of these games up, or all the other things I saw on the convention floor that just kept using the term, and every single time made me realise that in so doing, I now knew less about them than I would if almost any word was in that space.

What is ‘epic’ for?

I saw it being used to describe campaign sourcebooks and TTRPG material. It’s an interesting quirk of language that back when I was playing 3rd edition D&D, epic was a specific term used to describe the game after 20th level, which is to say, the point when the game’s rules started to break down and all the power design got exceptionally dumb. Of course that’s an old term from an older time – 3rd edition hasn’t been a meaningful frame of reference since the ye olden times of 2019 when Pathfinder 2e came out. In 4e — the best edition — the term is used to describe the last 10 levels of the game, where the game stops being about the movement of heroes and monsters and starts being about the will of demigods and resolutions of kingdoms.

Still, it looks to me now like ‘Epic’ is a thing that is used to describe a campaign that is long and has a huge scope. That’s cool and all, I can imagine a reason to want that, but I think this runs into a problem I have with the landscape of TTRPGs with prebuilt content in the first place. I don’t actually have much interest in modules or campaign setting information myself because I will almost always want to make my own, to tell my own story. Buying a campaign is weird enough to me, but then buying a big campaign, especially an extremely long campaign has all the aspirational purchase energy of the kind of person who buys roof racks for their sports utility vehicle that’s never going to be used to drive anywhere but work in the city and the shops.

Epic dungeons are somewhat in the same space in that they’re very large commitments of time and energy to a large space. Spaces are interesting to me because a space has an ideology and a purpose. The nature of a dungeon is that it’s a place with a purpose and you have to work out exactly what that means for a world — if there’s a dungeon the size of the Imperial City underneath the ground somewhere with its own ecosystem, I’m left wondering why it’s there, what’s the ideology of a structure like that.

Epic Dungeons are Dungeons, but big! Dungeons where you go down into them and what, have to spend time making beachheads and establishing places you can come back to? This is an idea that always feels to me like it works better for a videogame like Diablo, where there’s a system in place that lets you ‘save’ your progress, or a game world like Dark Souls where you can operate completely at your very edge of survival, where the nature of the place you’re going gives you a chance to restock yourself, and you don’t have to leave it except to empty your pockets.

And like, those worlds make for fun videogames but that’s a videogame? There’s no sense of verisimilitude or ideology of place in a videogame, certainly not compared to the vast freedom of a TTRPG. Yes, I’m saying Dark Souls is worse at giving a sense of place and a world than graph paper. And I should, because I’m right.

So like, what use is an Epic Dungeon as a thing you buy and drop into a world? It seems like you need a world that’s made for it, a world where it made sense for there to be an epic dungeon and a playstyle that supports it.

Epic challenges also feels like a strange place to start because what about them is epic? The scope of them? I guess that can be a way to make something feel big and impressive, but when a RPG sourcebook is promising ‘epic challenges’ I have to wonder how they make that feel that way. I remember keenly Exalted with its vast scope and how little that scope felt like it existed or mattered because the world kept winding around the same four or five people and the same villain. Are these games full of really good structural design that allows you to convey a deeply complicated scale of a problem with a huge variety of variables in a meaningfully handleable way? Or are they just full of art that shows very big things? Is it a dwarf with a big axe leaping through the air? Because that just feels like heroic fantasy, and I’ve got that.

I feel that in some cases there’s also an element of low-key snobbery around some of these ‘epic’ encounters where what they mean by ‘epic’ is ‘players can fail.’ Like there’s something about ‘epic challenges’ that means I know how to represent a real challenge, you don’t, and with all this there’s the precarity of a failure state hovering over things, a failure state that, being honest, for an appropriately epic sized kind of challenge, you won’t really see, because, like…

You don’t tend to survive epic failures.

Worlds don’t tend to survive epic failures.

It isn’t that any of the time, the impulse to use the word epic is a bad thing. It’s not like any of these companies are going to hurt for using a word that I personally just happen to think exists at the same level of writing effort as a gamer webcomic about two guys on a sofa complaining about the size of an Xbox controller.

I predict if Ettin gets to read this, he’s going to, before he finishes reading the article, send me a discord message saying ‘lol, epic.’

Check it out on PRESS.exe to see it with images and links!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

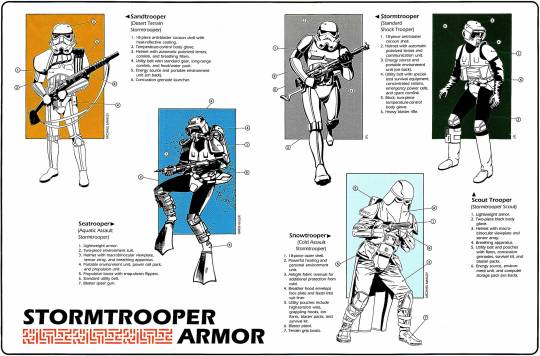

Stormtrooper armor variants for different environments and battlefield roles (art by Michael Manley, Greg Guler, and LFL archives, from the Imperial Sourcebook by Greg Gorden for West End Games’ D6 Star Wars RPG, 1989)

#Star Wars#Star Wars RPG#stormtroopers#stormtrooper#sci fi#Star Wars D6#Imperial Sourcebook#Star Wars the Roleplaying Game#Michael Manley#Greg Guler#Greg Gordon#WEG#West End Games#LFL#Lucasfilm LTD#SWEU#stormtrooper armor#snowtrooper#sandtrooper#scout trooper#seatrooper

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Gamers of a certain vintage may have fond memories of Beam Software’s 1993 version of Shadowrun on the SNES, or to a lesser extent, the 1994 Sega Genesis/Mega Drive game created by BlueSky Software.

Significantly fewer are likely to remember Shadowrun’s Japanese Sega CD adaptation from 1996, which not only was one of the last games launched on Sega’s failed add-on, but has never seen a full translation - official or otherwise - into English.

Unlike the more action-oriented SNES and Genesis versions, Shadowrun on Sega CD sticks fairly close to its source material, going as far as to incorporate actual dice rolls into combat. That fidelity can be chalked up to the involvement of Group SNE, who at that point were managing the Shadowrun franchise in Japan. The game’s scenario, co-written by Group SNE member Akira Egawa (江川晃), takes place in Tokyo and follows the cast of Egawa’s Shadowrun replays The Fallen Magician and The Nightmare Mark as they make their way through a series of episodic adventures.

The game’s cast represents a broad cross-section of Shadowrun archetypes. From left to right: Decker D-Head, Former Company Man Shiun, Street Samurai Rokudo, Physical Adept Sha, and Shaman Mao.

Setting-wise, this title draws from Egawa's somewhat controversial Tokyo Sourcebook supplement, a Japan-exclusive release that liberally rewrites the Shadowrun setting to make it more palatable to a Japanese audience. In Shadowrun’s early editions, the Japanese Imperial State (JIS) was presented as a militant, xenophobic superpower that eventually winds up invading and occupying San Francisco. Egawa’s Tokyo Sourcebook replaces this with a dysfunctional nation in the process of being torn apart by open warfare between rival megacorporations - a tweak that apparently didn’t impress hardcore Japanese fans, as several of them went on to write up an alternate JIS sourcebook, arguing that a villainous Japan was ultimately more interesting than a weak one.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stormtrooper armor [Star Wars Imperial sourcebook, 1989]

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s only just dawned on me that when Major Partagaz says Dedra came from “enforcement” he means the Enforcement branch of the ISB:

So if this is anything to go by, Dedra was hired in from outside any organisation within the Empire (basically to do dirty work the ISB/COMPNOR can wash their hands of).

This also means Dedra hasn’t just clawed her way to Supervisor as a woman in a male-dominated field - but from an unconventional position, a branch that’s looked-down on and even treated with suspicion within the organisation.

Furthermore, Internal Affairs (the branch that psychologically tortures the rest of the ISB) have a particular dislike for people from Enforcement…watch your back indeed, Dedra 😬

#star wars#andor#dedra meero#The ISB#ISB#the imperial sourcebook#dedra backstory clues that only raise MORE questions 🤔#this implies she wasn’t indoctrinated and groomed for her position#she chose it and sought it out willingly#much to think about#will share more from this book as soon as i can

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roman Republic Reading List

@hortensius : Hope this is helpful!

Comprehensive Exam, Major Field: Roman History, c. 400-100

Preliminary Reading List--Updated

General

Rosenstein, Rome and the Mediterranean (2012) [general survey]

Steel, End of the Roman Republic (2012) [general survey]

Flower, Roman Republics (2010)

Lomas, Roman Italy 338 BC-AD 200 (this is a sourcebook with introductory discussions)

Farney/Bradley, Peoples of Ancient Italy (2017) (a reference handbook)

Early Republic

Cornell, Beginnings of Rome (1996)

Forsythe, A Critical History of Early Rome (2006)

Armstrong, War and Society in Early Rome (2016)

Lomas, Rise of Rome (2018)

Smith, The Roman Clan (2009)

Armstrong, War and Society in Early Rome: From Warlords to Generals (2016)

Raaflaub (ed), Social Struggle in Archaic Rome, 2nd ed. (2008)* [edited volume with a lot of good chapters, especially Raaflaub, Cornell, Richard, Mitchell, Lindferski]

Terrenato, The early Roman expansion into Italy. Elite negotiation and family agendas (2019)

Middle Republic: Imperialism

Earlier period

Hölkeskamp, “Conquest, competition and consensus: Roman expansion in Italy and the rise of the nobilitas,” Historia 42 (1993) 12-39

Raaflaub, "Born to be Wolves? Origins of Roman Imperialism," in E. Harris & R. W. Wallace (eds.), Transitions to Empire in the Graeco-Roman World, 360-146 B.C. (1996) 273-314.

Terrenato, Early Roman Expansion into Italy (2019)

Fronda, Between Rome and Carthage (2011)

Motives, nature of Roman Expansion (the “Harris debate”)

Harris, War and Imperialism in Republican Rome (1979)

North, Development of Roman Imperialism (review of Harris), JRS 71 (1981) 1-9

Sherwin-White, Rome the Aggressor? (review of Harris), JRS 70 (1980) 177-181

Rich, Fear Greed and Glory: the Causes of Roman War Making in the Middle Republic, in Rich/Shipley, War and Society in the Roman World (1995) 38-68

Eckstein, Senate and General (1987)

Eckstein, Mediterranean Anarchy, Interstate War, and the Rise of Rome (2007)

Griffin, “Iure Plectimur. The Roman Critique of Roman Imperialism.” In Brennan and Flower (eds) East & West. Papers in Ancient History Presented to Glenn W. Bowersock (2008) [gives insight into why Roman historians give speeches to enemies of Rome, which could tie into presentation of captives]

Riggsby, Caesar in Gaul and Rome: War of Words (2021)

Provincialization, also response to Harris

Richardson, Hispaniae (1989)

Gruen, Hellenistic World and Coming of Rome (1986)

Kallett-Marx, Hegemony to Empire (1996)

Diaz Fernandez, Provinces and Provincial Command in republican Rome (2021)

Roman Political Culture (middle and late RP, and the democracy question)

Feig Vishnia, State, Society, and Popular Leaders in Mid-Republican Rome (2011) [possibly get rid of one of the older Gracchi treatments]

Hölkeskamp, Reconstructing the Roman Republic (2010)

Hölkeskamp, “The Roman Republic : government of the people, by the people, for the people ?,” Scripta Classical Israeilica 19 (2000) 203-223

Munzer, Roman Aristocratic Parties and Families (trans. 1999, orig. 1920)

Hopkins, Death and Renewal (1985) pp. 31-119

Lintott, Democracy in the Middle Republic

North, “Democratic Politics in Republican Rome,” Past & Present 126 (1990) 3-21

Millar, Crowd in Republican Rome (2002)

Millar, Political Character of the Classical Roman Republic, JRS 74 (1984) 1-19

Morstein-Marx, Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republican (2007)

North, Politics and Aristocracy in the Roman Republic, Classical Philology 85 (1990) 277-287

Lintott, Violence in Republican Rome (1999)

Wiseman, New Men in the Roman Senate (1972)

Archaeology/Topography and politics:

Davies, Architecture and Politics in Republican Rome (2017)

Russell, The Politics of Public Space in Republican Rome (2015)

Roman magistracies

Brennan Praetorship in the Republic (2000)

Beck, Duplá, jehnem Pina Polo (eds), Consuls and Res Publica: Holding High Office in the Roman Republic (2011)

Pina Polo, Quaestorship, Quaesorship in the Roman Republic (2019)

Wilson, Dictator: Evolutionof the Roman Dictatorship (2021)

Roman Religion/Religion and Politics

Beard, North and Price, Religions of Rome v. 1 and v. 2

Orlin, Temples, Religion and Politics

Rosenstein, Imperatores Victi

Gruen, Studies in Greek Culture and Roman Policy (various chapters on Magna Mater an Bacchanalia)

Stek, Cult Places and Cultural Change in Republican Italy

Beard, Roman Triumph (??)

Pedilla Peralta, Divine Institutions: Religions and Community in the Middle Republic (2020)

J. Mackay, Belief and Cult: Rethinking Roman Religion (2022)

Glinister, “Reconsidering ‘Religious Romanization’” YClS 33 (2006) 10-33

Diluzio, A Place at the Altar (2017) [on priestesses]

Middle Republic: Second Century/Lead-up to the Gracchi

Hopkins, Conquerors and Slaves (1981), esp. pp. 1-95

Rosenstein, Rome at War (2004)

Cornell, Hannibal’s Legacy: the effect of the Hannibal War on Italy, in Cornell/Rankov/Sabin, Second Punic War: a Reappraisal (1996)

Stockton, the Gracchi (1979) [older, “standard” treatment]

Earl, Tiberius Gracchus a Study in Politics (1963) [another old one; consult some of the reviews, e.g Brunt in Gnomon, Scullard in JRS, Crake in Phoenix)

Toynbee, Hannibal’s Legacy: the Hannibalic War’s Effects of Roman Life (1965) [very long; minimally understand the arguments and read reviews]

Brunt, Roman Manpower 225BC-AD14 (1971, republ. 1987) [very long]

There is a fair amount of archaeological work on second-century BC Italy.

Roman Italy, Romanization, Roman conquest of Italy:

Keay/Terrenato, Italy and the West (2001), just part 1 on the republic

Dench, From barbarians to new men: Greek, Roman, and modern perceptions of peoples from the central Apennines (1995)

Lomas, Rome and the Western Greeks (1993)

Bradley, Ancient Umbria: Stated Culture and Identity (2001)

Terrenato, Romanization of Italy: Global Acculturation or Cultural Bricolage, in Theoretical Roman Archaeology (1997) 20-27

Terrenato, Tam Firmum Municipium: the Romanization of Volaterrae and its Cultural Implications, JRS 88 (1998) 94-114

Terrenato, Early Roman Expansion into Italy (2019) [listed above]

Fronda, Between Rome and Carthage (2010) (intro section only)

Roselaar (ed), Processes of Integration and Identity Formation in the Roman Republic (2012) [lots of great chapters, especially by Roth, Rosenstein, Roselaar, Lomas, Patterson]

De Giorgi, Cosa and the Colonial Landscape of Colonial Italy (2019)

David, La Romanisation de l’Italie (1994) [= The Roman Conquest of Italy (1996)]

Glinister, “Reconsidering ‘Religious Romanization’” YClS 33 (2006) 10-33

Roth, Styling Romanization (2007)

Salmon, The Making of Roman Italy (1982)

Roman-Italian elite connections

Patterson, “Contact, Cooperation and Conflict in Pre-Social War Italy,” in Roselaar, 215-226

Patterson, “The Relationship of the Italian ruling Classes with Rome,” in Jehne/Pfeilschifter, Herrschaft und Integration? Rom und Italien in republikanischer Zeit (2006) 139-153.

Terrenato, "Tam firmum municipium: the Romanization of Volaterrae and its cultural implication" JRS 99 (1998) 94-114.

Wiseman, New Men in the Roman Senate

Late Republic: the Italian Question and the Social War

Brunt, “Italian Aims at the Time of the Social War,” JRS 55 (1965) 90-109

Dart, The 'Italian Constitution' in the Social War: A Reassessment (91 to 88 BCE) Historia 58 (2009), 215-224

Pobjoy, “The First Italia,” in Herring and Lomas, The Emergence of State Identities in Italy 187-211

Mouritsen, Italian Unification (1998)

Keaveney, Rome and the Unification of Italy, 2nd ed. (2005)

Howarth, Rome, the Italians, and the Land, Historia 48 (1999) 282-300

Nagle, “An Allied View of the Social War,” AJA 77 (1973) 367-78

Dart, The Social War, 91 to 88 BCE: A History of the Italian Insurgency against the Roman Republic (2014)

Late Republic: From Sulla to the Fall of Republic

Gruen, Last Generation of the Roman Republic, revised (1995) plus read reviews since this was not well received.

Piacentin, Financial Penalties in the Roman Republic (2022)

Taylor, Party Politics in the Age of Caesar (outdated: find reviews to understand the main arguments)

Morstein-Marx, Mass Oratory and Political power in the Late Republic (2008)

Rosillo Lopez, Political conversations in Late Republican Rome (2021)

Rosenblitt, Rome after Sulla (2019)

Pina Polo, The triumviral period: civil war, political crisis and socioeconomic transformations (2020)

Lintott, Violence in Republican Rome (1999)

Kelly, A History of Exile in the Roman Republic (2006)

Riggsby, Crime and Community in Ciceronian Rome (1999)

Augustus’ ‘Revolution’

Syme, Roman Revolution (1939) (a classic)

Raflaub/Toher (eds), Between Republic and Empire (1993)* [edited volume, excellent introductory chapter by Galsterer, plus other good historical chapters: Meier, Eder, Luce, Gruen]

Zanker, Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (1990)* (another classic)

Roman Military

Pfeilschifter, “The allies in the Republican army and the Romanization of Italy,” in Roth and Keller, Roman by Integration: Dimensions of Group Identity in Material Culture and Text (2007) 27-42

Jessica Clark. Triumph in Defeat: Military Loss and the Roman Republic. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2014

Rosenstein, Imperatores Victi: Military Defeat and Aristocratic Competition in the Middle and Late Republic (1990)

Keppie, Making of the Roman Army: from Republic to Empire (1998) [survey introduction]

Goldsworthy, Roman Army at War 100BC-AD 200 (1998)

Armstrong and Fronda (eds), Romans at War: Soldiers, Citizens and Society in Republican Rome (2020)

Daly, Cannae: Experience of battle in the Second Punic War (2003)

Slavery and Captives (starter bibliography)

Hopkins, Conquerers and Slaves (1981)

S. Joshel, Slavery in the Roman World (2010)

K. Bradley, Slavery and Rebellion in the Roman World, 140-70BC (1989)

K. Bradley, Slaves and masters in the Roman empire. A study in social control (1989)

K. Bradley, Slavery and society at Rome (1994)

K. Huemoeller, “Captivity for all ?: slave status and prisoners of war in the Roman Republic,” TAPA 115 (2021)

Henige, “He came, He Saw, We counted: the Historiography and Demography of Caesar's Gallic Numbers,” Annales de démographie historique (1998)

Lowe, "Prisoners, Guards, and Chains in Plautus, Captivi" AJP (1991)

Marshall, The Stagecraft and Performance of Roman Comedy (2006)

Richlin, Slave Theater in the Roman Republic (2017)

Scheidel, "Human Mobility in Roman Italy II: the Slave Population,” JRS (2005)

Scheidel and Harper, "Roman Slavery and the Idea of Slave Society" in Lenski/Cameron (eds) What Is a Slave Society (2018)

Scheidel, "The Roman Slave Supply" in Bradley/Cartledge (eds) Cambridge World History of Slavery (2011)

Thalmann, "Versions of Slavery in the Captivi of Plautus" Ramus (1996)

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Handler’s Guide is kind of an updated restatement of the original Delta Green sourcebook, plus a big pile of monster stats and such. The main draw is the timeline, which presents all the various conspiracies, year after year. I love a good timeline and this one is particularly engaging and detailed. I don’t honestly understand the level of work that went into it, but I appreciate it.

As I said, many, many conspiracies. Delta Green is two — the semi-official black op department and the extracurricular outlaw one hiding in the bureaucracy of the US Government. There are similar departments in other governments — Canadians, the Brits, the Russians, our own Majestic-12, the villainous Nazi Karotechia, Imperial Japan’s Black Ocean Society. There’s criminal organizations, cults, gangs, more cults, Nyarlathotep, aliens, threatening fungus. Wheels within wheels of all sorts. You can probably use a small slice of them and still put together a compelling campaign.

The books all have a dossier aesthetic. Reports, forms, photos are strewn across the page. Dennis Detwiller does all the illustration and I think it is perfect for the atmosphere of the game, effecting the look of bad or utilitarian photography (I feel like I should point at that Andrew Wyeth self-described his paintings as bad photographs). The art style grounds the game in procedure, in the concrete terms of evidence, and also illustrates how impossible the fight is, how out their depth everyone is, how doomed. There is much violence and terror here, and the aftermath of both. The total effect is disconcerting. That said, I really don’t like the cover art for this book, and the Agent Book cover doesn’t do it for me either. Can’t win them all, I guess.

#RPG#TTRPG#Tabletop RPG#Roleplaying Game#D&D#dungeons & dragons#Delta Green#Arc Dream#Cthulhu#Lovecraft

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Compact Assault Vehicle/Wheeled PX-10 were treaded combat vehicles designed to give a single soldier the firepower of a squad. Designed due to the Empire’s need to beef up their thinly spread military, PX-10s were armed with a powerful blaster cannon and could reach high speeds. Nevertheless, Rebel operatives came to connect the presence of PX-10s as an admission of reduced Imperial forces.

Source: Mission from Mount Yoda (Art: June Brigman/Karl Kesel; 1993)

First Appearance: Imperial Sourcebook (1991)

Read more on Wookieepedia.

#compact assault vehicle/wheeled px-10#px-10#galactic empire#galactic civil war#june brigman#karl kesel#star wars#expanded universe#star wars legends

11 notes

·

View notes