#Pyotr Kropotkin

Text

Excerpt in background from Pyotr Kropotkin’s 1902 text, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution

Reading leftist theory really helps you see de in a fresh light, there’s something i will reblog this with that has interesting implications for the in-game use of the word moralists :’]

Have a nice day!

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

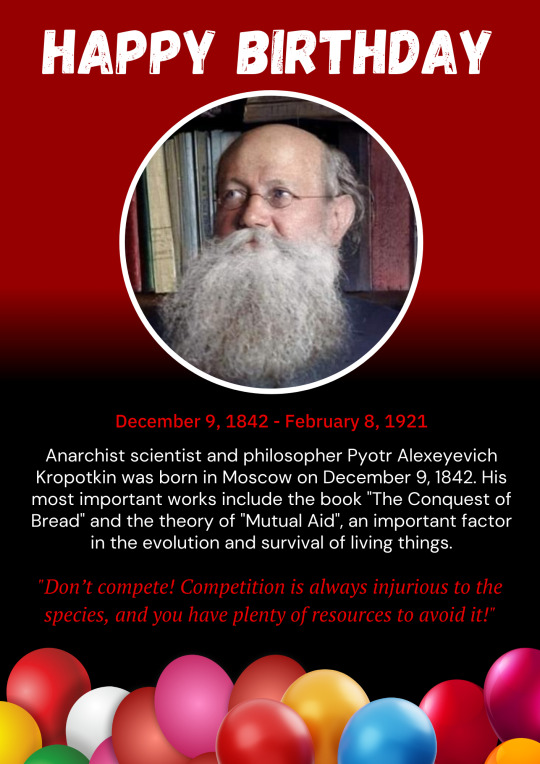

Today is the birthday of Anarcho-communist scientist and philosopher Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

To emancipate woman, is not only to open the gates of the university, the law courts, or the parliaments to her, for the "emancipated" woman will always throw her domestic toil on to another woman.

To emancipate woman is to free her from the brutalizing toil of kitchen and washhouse; it is to organize your household in such a way as to enable her to rear her children, if she be so minded, while still retaining sufficient leisure to take her share of social life.

It will come. As we have said, things are already improving. Only let us fully understand that a revolution, intoxicated with the beautiful words, Liberty, Equality, Solidarity, would not be a revolution if it maintained slavery at home.

Half humanity subjected to the slavery of the hearth would still have to rebel against the other half.

— Pyotr Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

#shanah tovah#l'shana tovah#Rosh Hashanah#marxism#marxist#communism#communist#marx#karl marx#socialism#socialist#Rosa Luxemburg#Emma Goldman#Alexandra Kollontai#Pyotr Kropotkin#Jewish#Jumblr#original#commie#ancom#left unity#leftism#leftist#moodboard

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

In its wide extension, even at the present time, we also see the best guarantee of a still loftier evolution of our race.

Pyotr Kropotkin, from Mutual Aid : A Factor of Evolution

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Esp) La conquista del pan. Piotr Kropotkin.

(Eng) The conquest of bread. Pyotr Kropotkin.

24 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The conceptions of good and evil were thus evolving not on the basis of what represented good or evil for a separate individual, but on what represented good and evil for the whole tribe. These conceptions, of course, varied with time and locality, and some of the rules, such, for example, as human sacrifices for the purpose of placating the formidable forces of nature — volcanoes, seas, earthquakes, — were simply preposterous. But once this or that rule was established by the tribe, the individual submitted to it, no matter how hard it was to abide by it.

Peter Kropotkin, Ethics

#cultural relativism#theology#anarchist morality#superstition#peter kropotkin#petr kropotkin#pyotr kropotkin#kropotkin#1922#kropokin 1922#ethics#ethics: origin and development#ethics origin and development

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy birthday, Emma Goldman! (June 27, 1869)

One of the most vital and influential anarchist thinkers in history, Emma Goldman was a spitfire and gadfly of rare ability. Born in what is now Lithuania to a Jewish family, Goldman grew up in poverty and educated herself, against the wishes of her controlling father. At age 16, Goldman moved with her sister to New York, where she became engaged in the radical social movements of the time, particularly after the Haymarket Square bombing of 1886. Before long, Goldman knew herself to be an anarchist. Arriving in New York City after spending some time upstate, Goldman met Alexander Berkman, who would become a lifelong collaborator and romantic partner. She became a major figure in the American anarchist movement, associating with prominent figures such as Errico Malatesta and Pyotr Kropotkin, while advocating for a social and individual view of anarchism, stressing personal freedom and opposition to the state. She became a boogeyman for the American ruling class, and was constantly harassed, finally being deported under the Anarchist Exclusion Act. She and Berkman were sent to Russia, where the dust was still settling from the October Revolution. Goldman's hesitance about the Bolshevik state soon turned to hostility, as Lenin's policies chafed against her anarchist beliefs. The suppression of the Kronstadt rebellion was the last straw, and Goldman and Berkman left Soviet Russia, settling in a number of different countries over the years. Goldman was a strong supporter of the anarcho-communists in the Spanish Civil War, writing a number of articles about the war, She died in 1940, after suffering a major stroke.

"Direct action, having proven effective along economic lines, is equally potent in the environment of the individual. There a hundred forces encroach upon his being, and only persistent resistance to them will finally set him free. Direct action against the authority in the shop, direct action against the authority of the law, direct action against the invasive, meddlesome authority of our moral code, is the logical, consistent method of Anarchism. Will it not lead to a revolution? Indeed, it will. No real social change has ever come about without a revolution. People are either not familiar with their history, or they have not yet learned that revolution is but thought carried into action."

420 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is not difficult, indeed, to see the absurdity of naming a few men and saying to them, "Make laws regulating all our spheres of activity, although not one of you knows anything about them!

Pyotr Kropotkin

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

[Video] Rare footage of anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin in 1917 at the age of 74

Peter Alekseyevich Kropotkin, (born December 9, 1842, Moscow, Russia—died February 8, 1921, Dmitrov, near Moscow), Russian revolutionary and geographer, the foremost theorist of the anarchist movement. Although he achieved renown in a number of different fields, ranging from geography and zoology to sociology and history, he was eternalized for the life of a revolutionist.

Early life and conversion to anarchism

The son of Prince Aleksey Petrovich Kropotkin, Peter Kropotkin was educated in the exclusive Corps of Pages in St. Petersburg. For a year he served as an aide to Tsar Alexander II and, from 1862 to 1867, as an army officer in Siberia, where, apart from his military duties, he studied animal life and engaged in geographic exploration.

Kropotkin’s findings won him immediate recognition and opened the way to a distinguished scientific career. But in 1871 he refused the secretaryship of the Russian Geographical Society and, renouncing his aristocratic heritage, dedicated his life to the cause of social justice. During his Siberian service he already had begun his conversion to anarchism—the doctrine that all forms of government should be abolished—and in 1872 a visit to the Swiss watchmakers of the Jura Mountains, whose voluntary associations of mutual support won his admiration, reinforced his beliefs. On his return to Russia he joined a revolutionary group, the Chaiykovsky Circle, that disseminated propaganda among the workers and peasants of St. Petersburg and Moscow. At this time he wrote “Must We Occupy Ourselves with an Examination of the Ideal of a Future System?,” an anarchist analysis of a postrevolutionary order in which decentralized cooperative organizations would take over the functions normally performed by governments.

He was imprisoned in 1874 for his ideas but was freed by his comrades in a sensational escape 2 years later, fleeing to western Europe, where his name soon became revered in radical circles. The next few years were spent mostly in Switzerland until he was expelled at the demand of the Russian government after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II by revolutionaries in 1881. He moved to France but was arrested and imprisoned for 3 years on trumped-up charges of sedition. Released in 1886, he settled in England, where he remained until the Russian Revolution of 1917 allowed him to return to his native country.

Philosopher of revolution

Kropotkin’s aim, as he often remarked, was to provide anarchism with a scientific basis. In Mutual Aid, which is widely regarded as his masterpiece, he argued that, despite the Darwinian concept of the survival of the fittest, cooperation rather than conflict is the chief factor in the evolution of species. Providing abundant examples, he showed that sociability is a dominant feature at every level of the animal world. Among humans, too, he found that mutual aid has been the rule rather than the exception. He traced the evolution of voluntary cooperation from the primitive tribe, peasant village, and medieval commune to a variety of modern associations—trade unions, learned societies, the Red Cross—that have continued to practice mutual support despite the rise of the coercive bureaucratic state. The trend of modern history, he believed, was pointing back toward decentralized, nonpolitical, cooperative societies in which people could develop their creative faculties without interference from rulers, clerics, or soldiers.

In his theory of “anarchist communism,” according to which private property and unequal incomes would be replaced by the free distribution of goods and services, Kropotkin took a major step in the development of anarchist economic thought. Kropotkin envisioned a society in which people would do both manual and mental work, both in industry and in agriculture. Members of each cooperative community would work from their 20s to their 40s, four or five hours a day sufficing for a comfortable life, and the division of labour would yield a variety of pleasant jobs, resulting in the sort of integrated, organic existence.

To prepare people for this happier life, Kropotkin pinned his hopes on the education of the young. To achieve an integrated society, he called for education that would cultivate both mental and manual skills. Due emphasis was to be placed on the humanities and on mathematics and science, but, instead of being taught from books alone, children were to receive an active outdoor education and to learn by doing and observing firsthand, a recommendation that has been widely endorsed by modern educational theorists. Drawing on his own experience of prison life, Kropotkin also advocated a thorough modification of the penal system. Prisons, he said, were “schools of crime” that, far from reforming the offender, subjected him to brutalizing punishments and hardened him in his criminal ways. In the future anarchist world, antisocial behaviour would be dealt with not by laws and prisons but by human understanding and the moral pressure of the community.

Kropotkin combined the qualities of a scientist and moralist with those of a revolutionary organizer and propagandist. For all his mild benevolence, he condoned the use of violence in the struggle for freedom and equality, and, during his early years as an anarchist militant, he was among the most vigorous supporters of “propaganda by the deed”—acts of insurrection that would supplement oral and written propaganda and help to awaken the rebellious instincts of the people. He was the principal founder of both the English and Russian anarchist movements and exerted a strong influence on the movements in France, Belgium, and Switzerland.

Return to Russia of Peter Alekseyevich Kropotkin

Events took an unexpected turn with the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in 1917. Kropotkin, by this time age 74, hastened to return to his homeland. When he arrived in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) in June 1917 after 40 years in exile, he was greeted warmly and offered the ministry of education in the provisional government, a post he brusquely declined. Yet his hopes for the future were never brighter, because in 1917 the organizations that he thought might form the basis of a stateless society—the communes and soviets, or soldiers’ and workers’ councils—suddenly began to appear in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

With the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917, however, his earlier enthusiasm turned to bitter disappointment. “This buries the revolution,” he remarked to a friend. The Bolsheviks, he said, have shown how the revolution was not to be made—that is, by authoritarian rather than libertarian methods. Kropotkin’s last years were devoted chiefly to writing a history of ethics, one volume of which was completed. He also fostered an anarchist cooperative in the village of Dmitrov, north of Moscow, where he died in 1921. His funeral, attended by tens of thousands of admirers, was the last occasion in the Soviet era when the black flag of anarchism was paraded through the Russian capital.

Kropotkin’s life exemplified the high ethical standard and the combination of thought and action that he preached throughout his writings. He displayed none of the egotism, duplicity, or lust for power that marred the image of so many other revolutionaries. Because of this he was admired not only by his own comrades but by many for whom the label of anarchist meant little more than the dagger and the bomb. The French writer Romain Rolland said that Kropotkin lived what Leo Tolstoy only advocated, and Oscar Wilde called him one of the two really happy men he had known.

#κροπότκιν#kropotkin#piotr kropotkin#peter kropotkin#russia#russian#anarchist#anarchism#anarchy#newsreel#old#old film#old movie#black and white#Youtube

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

What makes a leftist?

There's a whole lot of leftists on the interwebs today, mostly Americans, and every once in a while we find out that a particular person (this week it was Ana Kasparian) is not actually a leftist at all and completely fine with parroting far right talking points.

And we notice that although they seem to have been an advocate for social justice and marginalized groups, they have mainly been reacting to whatever bullshit the right is pulling. Understandable,but not conducive to actually pass out the politics of someone. Being against the genocide of trans people in the US doesn't make one a lefitst, it just makes you a decent person.

Which begs the question: What makes a leftist?

For me it's anti-capitalism. It is also anti-fascism, but even liberals can be anti-fascists.

But anti-capitalism IMO is a stance you cannot go back on. Once you understand how capitalism works, once you grasp the underlying exploitation and the fundamentially incompatable interests of working class and owning class, you cannot go back. You cannot wake up one day thinking: You know what? The means of productions don't belong into the hand of the workers.

That is the fundamental difference between a liberal and a leftist. Liberals still uphold capitalism. They can be the nicest people and super involved with progressive causes, but at best they are ignorant and believe the lie that capitalism is just how things are.

It can be difficult to parse however if a certain person is an anticapitalist or not. Again, you don't need to be a leftist to be against the growing fascism in Europe and North America, against ecological destruction, against trans genocide, against police brutality, etc. That just makes you an empathetic person.

It is also normal to be confused as colloquially terms like left, socialism, anarchy, communism are used wildly outside their actual meaning. Not to mention the buzzwordsalad spewed by the right. Consequently being a leftist also means you have read up at least a little on theory and understand that for example Scandinavia isn't socialist at all since the workers don't own the means of production. That politicians like Bernie Sanders are just nicer liberals, social democrats in his case, believing in a mixed economy. That there are no viable leftist political parties anywhere in Europe or North America, no matter what they call themselves.

Being a leftist can mean that you fall into one of the many schools of thought between Marxism, socialism, communism, anarchism, syndicalism, or their various combinations or none of them. But it means you are an anti-capitalist and understand capitalism as the underlying source of all intersectional ills that plague humankind today. From racism, climate catastrophe, income inequality, nazis to war and Elon Musk. It's all connected. It's systemic.

Further reading/watching:

Hadas Thier - A people's guide to capitalism (great starter)

Marx / Engels - The manifesto of the communist party

Naomi Klein - The Shock Doctrine

Everything by Angela Davis, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, Emma Goldman, Rosa Luxemburg, Mark Fisher, Pyotr Kropotkin, Antonio Gramsci

Thought Slime

Renegade Cut

Second Thought

More Perfect Union

Unlearning Economics

Carlos Maza

The Leftist Cooks

Then & Now

NonCompete

#leftism#socialism#communism#anarchism#anticapitalism#anti capitalism#fuck capitalism#antifa#antifacism#late stage capitalism#neoliberalism#breadtube#lefttube#layperson talking politics#intersectionality#marx#marxism#engels#thought slime#renegade cut#second thought#carlos maza#more perfect union#unleraning economics#the leftist cooks#then & now#noncompete#rosa luxemburg#emma goldman

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I'd love an anarchist reading list from 'When Times are Dire'. I read it voraciously and then I read it again. I had a conversation tonight wherein I referenced your work like 3 times. I'm looking especially for the "transforming" quote and its' reference. Thank you so much. I love your writing.

-Deva

Oh my gosh that is so delightful. Thank you! 🥲

Of course! They're both cited in the text of When Times are Dire in some way, I think, but for easy reference:

The Conquest of Bread, Pyotr Kropotkin (1892)

"Whence comes the revolution, and how will it announce its coming? None can answer these questions. The future is hidden. But those who watch and think do not misinterpret the signs: workers and exploiters, Revolutionists and Conservatives, thinkers and men of action, all feel that the revolution is at our doors. Well! What are we to do when the thunderbolt has fallen? We have all been studying the dramatic side of revolution so much, and the practical work of revolution so little, that we are apt to see only the stage effects, so to speak, of these great movements; the fight of the first days; the barricades. But this fight, this first skirmish, is soon ended, and it is only after the overthrow of the old constitution that the real work of revolution can be said to begin."

Two Cheers for Anarchism, James C. Scott (2012)

"What if we were to ask what kind of people a given activity or institution fostered? Any activity we can imagine, any institution, no matter what its manifest purpose, is also, willy-nilly, transforming people."

Harry also reads Saul Alinsky's Rules for Radicals (1971), which isn't anarchism but more like strategies for political organizing. Interestingly, there was a rightwing response written by Michael Charles Masters in 2012 called Rules for Conservatives: A Response to Rules for Radicals by Saul Alinsky that claims to be "the playbook to save America from liberal community organizers." So you can see the ripple effect through the past decades.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the same way, those who man the lifeboat do not ask credentials from the crew of a sinking ship; they launch their boat, risk their lives in the raging waves, and sometimes perish, all to save men whom they do not even know. And what need to know them?

'They are human beings, and they need our aid - that is enough, that establishes their right - To the rescue!'

— Pyotr Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conquering Bread

Today was our Discord's first book club meeting reading 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘊𝘰𝘯𝘲𝘶𝘦𝘴𝘵 𝘰𝘧 𝘉𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥 by Pyotr Kropotkin. First chapter is pretty spicy, had quite a bit of notes (5 and a half pages of notes on 8-1/2x11 paper), even if just starter stuff - can't wait to read the rest of it!And since I'm one of the ancoms in the chat and generally just really excited to read the Bread Book itself, I led discussion - and you could tell I am not used to leading.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book recommendation; X + Y (a mathematician’s manifesto for rethinking gender) by Eugenia Cheng

Rather than think about men vs women, consider the power structure in place. She develops the idea of ingressive and congressive people, and it reads very much like mutual aid by Pyotr Kropotkin despite not being explicitly communist/anarchist.

Great read, especially when paired with her other book, the art of logic.

2 notes

·

View notes