#loïc wacquant

Text

REBOTA REBOTA, Y EN TU CARA EXPLOTA, performance de Agnès Maéeus et Quim Tarrida, avec Agnés Matéus, 1h15, 2018 - et vu en 2024 au Théâtre de la Bastille, Paris.

Commençons par dire que ce spectacle, vu en 2024 a été crée il y a 6 ans, à Genève (selon le site théâtre contemporain). En septembre 2018, quelle était la place du féminisme dans nos discours, dominants et dominés ? C'était un an après, à deux semaines près, qu'Alyssa Milano propose de partager, suite à la révélation de l'affaire Weinstein, sous le hashtag #metoo, les violences sexistes et sexuelles subies par les femmes par des hommes. Cette création a aussi lieu dans un contexte espagnol où la prise en charge des violences sexistes et sexuelles aurait permis une baisse du nombre de féminicides selon les médias généralistes nationaux et internationaux. Dans un bref entretien, Agnés Mattéus conteste cette prise en charge effective quand, en 2017, le travail sur la pièce commence - tandis que certaines sociologues féministes, dont par exemple Gloria Casas Vila, critiquent davantage un effet de comptage (quel meurtre est effectivement compté comme féminicide ?), permettant de donner alors l'impression que le nombre de féminicides décroît alors qu'il n'en est rien. En 2023, certains médias généralistes soulignent une ré-augementation des chiffres espagnols de féminicides, se réalignant sur ceux de 2008, soulignant que dans la moitié de ces meurtres, les plaintes avaient été déposées contre les agresseurs, devenus meurtriers et/ou que les agresseurs étaient récidivistes, parfois déjà meurtriers. Si ce type de média souligne cette inversion, on peut donc supposer qu'il ne s'agit que de la partie emergée d'un iceberg bien fat, bien réel, bien patriarcal, et qu'en dessous grouille une bouillie dégueu mais bien organisée du féminicide - à l'instar de l'inceste, comme le montre par exemple Dorothée Dussy dans Le berceau des dominations.

Dire également que je m'interroge sur le travail de collaboration entre Quim Tarrida et Agnés Matéus. Dans le même entretien, qu'elle et il donne au théâtre de la Bastille, la langue française, que parle Agnés Matéus et que ne parle pas Quim Tarrida, donne le primat à Agnés Matteus. Mais j'avoue avoir eu ce réflexe de me demander ce qu'un homme pouvait bien avoir à faire dans la mise en scène d'une femme parlant de féminicides, dont la plus part sont commis par des hommes. Et si tous les hommes ne sont pas des meutriers, des violeurs, etc, la quasi-totalité des hommes de son âge et de sa nationalité (Quim Tarrida est né en 1967) ont été socialisés dans un monde où la masculinité était valorisée, et hiérarchiquement instaurée supérieure au genre féminin. Si l'on comprend que le travail naît d'une précédente collaboration sur les violences policières, et que ce travail précédent naît d'une rencontre lors de leurs engagements militants, malgré tout : comment s'articulent les regards, différemment socialisés, de Agnés Matteus et Quim Tarrida pour aboutir à REBOTA REBOTA, Y EN TU CARA EXPLOTA, notamment sur le corps de Agnés Mattéus ? Cela pourrait informer ma lecture, mais je n'y ai pas accès, pas directement, seulement par supposition critique (car, d'expérience, fréquenter un milieu politisé, quand il ne s'agit pas directement de cercles féministes engagés, ne permet pas une déconstruction du regard, d'un regard dominant)

Et maintenant, décrivons ce que propose Ca rebondit ça rebondit et ça t'éclate en pleine face. Cela sera moins qu'une description linéaire et exhaustive, ne m'arrêtant que sur certains tableaux et détails qui m'ont paru particulièrement signifiants. Dire peut-être cela, d'abord : REBOTA REBOTA, Y EN TU CARA EXPLOTA est une succession de tableaux au centre desquels se trouve Agnés Matéus.

L'âge. La pièce commence par Agés Matéus dansant masquée, d'un masque de clown horrifique. Ainsi, c'est son corps que l'on voit et regarde. En 2024, le corps de Agnés Matéus, serré dans son pantalon strassé or, son ventre rebondi, a peine dénudé au dessus du nombril donne l'image d'un corps butch, ou d'un corps vieilli, ne répondant plus aux standards patriarcaux d'une certaine minceur. Qu'en est-il de son corps d'il y a 7 ans ? A-t-il changé, et comment ? Vieilli pour sûr, Agnés Matéus dans le texte, et dans les possibles endroits d'improvisation le signale, insiste sur la question de l'âge. Si je suis particulièrement sensible à cette question d'âge, dans les rapports de genre, c'est qu'elle me concerne : les regards changent, le crédit à la parole dans certains contextes aussi. Qu'est ce que faire tourner une pièce pendant 6 ans ? Qu'est-ce qu'expérimenter les changements physiques ? D'autant qu'est soulignée l'énergie de Agnés Matéus, qui tient l'heure quinze que dure Ca rebondit quasi seule sur scène. Mais là aussi, des questions se posent, techniques : quelle place de repos permettent les interludes filmés ? Sont-ils là pour leur qualité intrinsèque, de séquences filmées introduisant un autre rythme à la pièce, et/ou sont-ils présents pour permettre que Agnés Matéus tienne ? Cette question peut se poser, mais pas de la même manière, en fonction de la catégorie d'âge à laquelle l'acteur.ice appartient, car les contingences et les nécessités ne sont pas les mêmes, et donc ne disent, in fine, pas les mêmes choses sur les questions posées par la pièce elle-même. Ici, les premières séquences filmées m'ont moins conduit à regarder les états de délabrements de certaines scènes urbaines qu'à penser au délabrement, en cours mais encore à venir, du corps de Agnés Matéus. Et ces figurations de ruines, par leurs lents travellings dont on sait qu'ils vont, à un moment ou à un autre, figurer une morte, ne m'ont par renvoyées en tant que tel au corps de la performeuse. C'était un autre espace, un autre temps qui se raccorde à l'âge seulement par le comptage, le listage qui vient à la fin de la pièce des femmes mortes, dont l'âge à chaque fois est indiqué. Aucun âge n'est épargné, pas davantage les petites filles que les grand-mères, les jeunes femmes ou les femmes dans la fleur de l'âge. Aucune. Alors, cette question de l'âge se pose pour moi à nouveau dans l'espace où justement d'autres âges que celui de la performeuse, son âge réel, aurait pu être figuré : dans les séquences filmées. Pas d'enfants, pas de jeunes filles, toujours des mortes anonymisées, sans visage, dont on voit qu'il peut s'agir du corps de la performeuse - dont l'âge, là, varie encore par l'absence du visage.

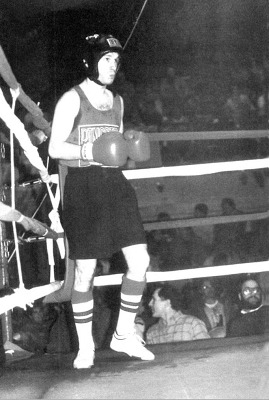

La chute. Après la danse, il y a ce moment que j'ai trouvé très beau, de la chute du corps de Agnés Matéus. La beauté terrifiante de la chute sous les coups. Encaisser les coups et se relever. Être cueillie par les coups. Ne pas répondre, ne pas frapper. En miroir négatif, les poings des hommes pauvres qui apprennent à frapper contre un sac de sable dans la moiteur de salles de sports, à Chicago ou ailleurs, en France, pour se maintenir dans une dignité - je pense à ce qu'en écrit, par exemple, Loïc Waquant, ou encore Jérôme Beauchez (mais moins, ici, et à regret ne les ayant pas (encore lu) aux sociologues ayant travaillé sur les femmes dans les sports de combat, comme Christine Mennesson ou encore Natacha Lapeyroux). L'apprentissage de la chute n'est pas corrélée à l'apprentissage du coup, j'y vois plutôt la réponse de deux précarités, l'une sociale, l'autre de genre, où celui féminin est économiquement, symboliquement plus précaire, vacillant. Mais que penser de la beauté de ces chutes ? Que penser de la beauté dans une telle performance ? Comment la beauté peut se conjuguer à l'horreur de ce qui est dit ? A l'extrême, on pense au texte de Rivette dénonçant l'abject du travelling dans Kapo. S'en détache malgré tout cette chute par ce que permet de percevoir sa répétition, dans ce que l'on perçoit par ce corps, et ce malgré ou grâce à la beauté, ce que permet la répétition c'est de percevoir précisément ce qui n'est pas figurer : la force qui pousse à terre Agnés Matéus, cette lumière qui la pousse, c'est insaisissable comme le patriarcat et au moins aussi éblouissant, ça fait cligner de l'oeil mais malgré tout, on continue à regarder, à accepter. C'est ce déplacement du corps qui chute, par la répétition de la chute, qui permet que l'on perçoive notre propre fascination, la fascination qu'impose la domination, biche en plein phare, notre stupéfaction, notre immobilité face aux coups que l'on sait, même si on ne les voit pas.

Le one-woman show. J'ai pris plaisir à ce one-woman show grinçant, en robe de mariée saupoudrée de paillettes d'or (interdites désormais), comme d'une femme sous cloche, dans une boule à neige, une boîte à musique dont la danseuse dit avec le sourire des insanités. Simple, drôle, jusqu'à et avec son craquement Frida Ka(h)lo. J'ai trouvé malin que les références connues se tissent progressivement avec celles inconnues - mon coup au cœur quand Bessette se fait invisibiliser, inconnue. J'ai trouvé pertinent le moment de réflexion sur l'arbre Kahlo qui cache la forêt des femmes : combien de fois avons-nous vu la vie d'une qui devient emblème de toutes, effaçant les spécificités de chacune, un féminisme non intersectionnel, encore que Kahlo pose la question du validisme, une intersection non négligeable. Agnés Matéus m'a fait penser à une Blanche Gardin, une Elodie Poux, une Florence Foresti. Ce sont des ressorts similaires : montrer ce qui est dit en le confrontant à la réalité. Analyse de l'écart du symbolique, du discursif et du réel pour en montrer l'absurde - et l'absurde faire rire, à tout coup, même si c'est déjà connu, même si c'est jaune.

Le lancer de couteaux. La mise en danger, réelle, m'a glacée. Je n'ai pas voulu, je ne voulais pas. La tension. Qu'en dire ? Que le spectacle est bien rôdé ? Que je n'ai jamais été au cirque (ou plutôt une seule fois) ? Que ce n'était pas une scène de cirque dont on sait que tout est maîtrisé, y compris le danger ? Que le danger venait là davantage de la peur de Agnés Matéus que du lanceur ? Que je l'ai imaginée à chaque fois défaillir de peur, et se précipiter sous le couteau pour le fuir ? Qu'à cet endroit quelque chose se renverse du rapport au danger ? Est-ce une métaphore du féminicide : le danger pris dans le sang-froid du meurtrier (n'en faisons pas un fou) est de bouger, et de provoquer, et de fuir seulement après ? Il faudrait disparaître à soi-même pour ne pas disparaître tout court, mourir ? Mais le danger passé, est-il possible de sortir de l'état de mort dans lequel il nous plonge (et qui se traduit, assez littéralement, par la tête de Matéus dans une brouette de terre) ? Il n'y a pas de résolution de cette question, car elle est irrésolvable. Insupportable ? Une dame au premier rang s'est levée pour sortir du théâtre, un peu avant la fin de la pièce, quand les noms des femmes tuées défilaient, trop vite pour qu'ils soient lisibles. Matéus et Tarrida ne donnent pas de réponses, ni au pourquoi ni au comment, il s'agit d'une performance de constats, fragmentés et parfois rendus sensibles.

#Agnés Matéus#REBOTA REBOTA#Gloria Casa Vila#Quim Tarrida#performance#Ca rebondit ça rebondit et ça t'éclate en pleine face#Dorothée Dussy#féminicide#poésie critique#anne kawala#christine mennesson#natacha lapeyroux#loïc wacquant#jérôme beauchez#jacques rivette#blanche gardin#élodie poux#florence foresti

1 note

·

View note

Text

Not all free persons are white (nor are they equal or equally free), but slaves are paradigmatically black. And because blackness serves as the basis of enslavement in the logic of a transnational political and legal culture, it permanently destabilizes the position of any nominally free black population. Stuart Hall might call this the articulation of elements of a discourse, the production of a “non-necessary correspondence” between the signifiers of racial blackness and slavery. But it is the historical materialization of the logic of a transnational political and legal culture such that the contingency of its articulation is generally lost to the infrastructure of the Atlantic world that provides Frank Wilderson a basis for the concept of a “political ontology of race.” The United States provides the point of focus here, but the dynamics under examination are not restricted to its bounds. Political ontology is not a metaphysical notion, because it is the explicit outcome of a politics and thereby available to historic challenge through collective struggle. But it is not simply a description of a political status either, even an oppressed political status, because it functions as if it were a metaphysical property across the longue durée of the premodern, modern, and now postmodern eras. That is to say, the application of the law of racial slavery is pervasive, regardless of variance or permutation in its operation across the better part of a millennium.

In Wilderson’s terms, the libidinal economy of antiblackness is pervasive, regardless of variance or permutation in its political economy. In fact, the application of slave law among the free (that is, the disposition that “with respect to the African shows no internal recognition of the libidinal costs of turning human bodies into sentient flesh”) has outlived in the postemancipation world a certain form of its prior operation—the property relations specific to the institution of chattel and the plantation-based agrarian economy in which it was sustained. [Saidiya] Hartman describes this in her 2007 memoir, Lose Your Mother, as the afterlife of slavery: “a measure of man and a ranking of life and worth that has yet to be undone . . . a racial calculus and a political arithmetic that were entrenched centuries ago.” On that note, it is not inappropriate to say that the continuing application of slave law facilitated the reconfiguration of its operation with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, rather than its abolition (in the conventional reading) or even its circumscription “as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted” (on the progressive reading of contemporary critics of the prison-industrial complex). It is the paramount value of Loïc Wacquant’s historical sociology, especially in Wilderson’s hands, that it provides a schema for tracking such reconfigurations of anti-blackness “from slavery to mass imprisonment” without losing track of its structural dimensions, its political ontology.

Jared Sexton, People-of-Color-Blindness: Notes on the Afterlife of Slavery

#quote#jared sexton#slavery#antiblackness#carcerality#frank b. wilderson iii#saidiya hartman#loïc wacquant#afropessimism#*ayden

0 notes

Text

submitted final essay but I keep thinking about all the ways it is bad and what I should’ve fixed and how it could’ve been better despite the fact that I worked on it near constantly for three weeks like 8-18 hours a day. also I am literally recovering from intensive surgery and on so many narcotics and should be worrying about that (and my Other final essay I have yet to write) and yet. And yet!!!! Fuck.

#Chaya speaks#I’m so tired of living like thisssss#has anyone ever felt good about a paper they’ve written ever#I just kept reading my research materials in a state of pure jealousy#fuck Loïc wacquant for being so GOOD at his job but also being a white french man. Like come on

0 notes

Text

First of all, the egalitarian ethos and pronounced color-blindness of pugilistic culture are such that everyone is fully accepted into it so long as he submits to the common discipline and "pays his dues" in the ring.

Loïc Wacquant Body and Soul: Notebooks of an apprenctice boxer. (2004) Pg 10

0 notes

Photo

This month’s Office Hours is worth the read. Forrest Stuart, MacArthur Grant recipient and author of Ballad of the Bullet: Gangs, Drill Music, and the Power of Online Infamy, shares some significant moments thus far in his career, offers valuable insight on some of his favorite books—and may surprise you with his bedtime reading habits.

ML: What are you reading now?

FS: For the last decade or so, I’ve developed the habit of keeping two books on my bedside table at any given time, reading a bit of both each night as I wind down. The first is typically a newly published ethnography, which helps me stay current in my field. Right now, it’s Policing the Racial Divide: Urban Growth Politics and the Remaking of Segregation, by Daanika Gordon. The book takes us throughout daily life in Rust Belt city via police ride-alongs, community meetings, and other public events. Gordon weaves a fresh analysis of how police departments do more than merely respond to the racialized issues emanating from histories of segregation; rather, they are key, active authors in creating and reproducing the urban color line. As urban sociologists, geographers, and political economists continue to take policing more seriously, this book feels like the first of a new era of much-needed scholarship.

The second book in my bedside rotation is always a fantasy novel. My obsession with the genre is something I’ve kept very quiet around colleagues, until now, I suppose. I’m currently wrapping up the fifth and final book of Brent Weeks’s Lightbringer series. It follows a young orphan challenging an empire ruled by religious authoritarianism, palace intrigue, and, yes, a healthy dose of magic. Weeks’ series is deeply ethnographic, with complex worldbuilding that stretches between the multiple thousand-page books. I’m especially fond of the detailed maps on the first few pages, which let me follow the protagonist’s journey across mountain ranges and oceans. In my first book, Down, Out, and Under Arrest, which documents policing’s ripple effects across everyday life in LA’s Skid Row, I designed and included a map of the neighborhood as a kind of homage to my favorite fantasy writers. I also find myself dog-earing pages of fantasy novels when I spot literary tricks and grammatical moves I hope to try out in my own prose.

ML: What book has had the most impact on your career?

FS: Without a doubt, the book that has had the biggest impact on my career is Mitchell Duneier’s masterful 1999 book, Sidewalk. It’s an ethnography of Black, precariously housed magazine vendors who set up shop on Sixth Avenue in New York’s Greenwich Village. Through Duneier’s fieldwork, we see how the vendors become “eyes on the street” to enhance safety for vulnerable populations, provide mentorship to young Black men in the local service economy, and act as key “nodes” that link residents across racial, class, and generational lines. Throughout his analysis, Duneier “zooms out,” tracing how structural forces, like deindustrialization and zero-tolerance policing, have aligned to bring the vendors to this location and hound their continued existence. He also “zooms in” to the interactional level using conversation analysis (CA), measuring split second pauses and turn-taking to show how vendors’ seemingly innocuous chatter with passersby constitutes a form of “interactional vandalism” that intimidates women and reinforcing stereotypes about Black men. Stylistically, Sidewalk often reads more like a novel, with flowing dialogue punctuated with beautiful black and white photos from the Chicago Tribune’s Ovie Carter.

A few years after its release, Sidewalk was also the subject of arguably the most famous book review symposium in sociology, generating a heated back-and-forth between Duneier and Berkeley’s Loïc Wacquant on the issues of transparency, representation, and the role of urban ethnography in the fetishization of poverty. I return to the debate every time I start a new project.

ML: What is your favorite book to teach?

FS: In just about every class I teach, I look for new ways to put Mary Pattillo’s now-classic Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril among the Black Middle Class on the syllabus. I start by showing students how Pattillo uses the opening “setting” section—often a perfunctory, forgettable part of a book—to set up a wonderful empirical puzzle. Walking the reader through a tour of the “Groveland” neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side, Pattillo paints a scene where, because of intergenerational segregation, middle class Black residents, banks, and churches share walls and sidewalks with low-income Black residents, subsidized housing, and check cashing outlets. How, Pattillo leads us to ask, does this unique cross-class proximity structure everyday life and social organization for the Black middle class? In answering, Pattillo deploys several analytical strategies that I pass on to my students. She shows the underestimated power of creating typologies, finding variation among Groveland residents (for example, whether they internalize or merely perform “street culture”), and then showing how variation along these lines leads to differing outcomes. She also leverages the power of “deviant” cases to show how certain people blur the boundaries of ideal types, forcing us to rethink and refine many of our taken-for-granted theoretical categories. The book is simultaneously a lesson on how to write about participants and their communities, especially those who occupy marginalized social positions. Pattillo’s empathy and respect shine through on every page, from the pseudonyms she chooses to the biographical details she shares (and doesn’t share) with the reader.

ML: Do you have a favorite moment as a researcher, maybe an encounter that unexpectedly changed your way of thinking or the direction of a project?

FS: I’m proud of the fact that I’ve had quite a few occasions where an experience radically reshaped my prior assumptions and the direction of the entire project, usually for the better. One that I won’t ever forget came in the early stages of my research for my second book, Ballad of the Bullet. The book follows a group of young Black men on Chicago’s South Side as they strive for popularity—and an income—in the digital economy. They spent their days recording and uploading a homemade genre of gangsta rap, sometimes referred to as “drill music” to YouTube. Then, they turn to their multiple social media platforms to try to authenticate the hardened criminal personas they crafted in their songs. A music video about committing a drive-by shooting might be accompanied on Twitter with talk of potential victims and Instagram photos holding a gun out of a car window. When done well, it’s easy to start believing that young men in the drill scene might actually do the deeds they rap about. That’s their intention, after all—to lure in voyeuristic, middle-class audiences looking for a glimpse into ghetto life.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I had bought into quite a few of their performances of “badness.” Of course, I knew that they weren’t nearly as violent as they wanted their typical audiences to believe. But when I really got to know them, I learned that the vast majority of their posts weren’t just exaggerations, they were utter fabrications. Some of the men known as the most violent had never actually fired a gun, and even avoided conflict. Focusing instead on these young men’s inauthenticity, and their strategies of performance, let me highlight their savvy creativity amid some incredible structural obstacles.

ML: What is the best career advice you ever received?

FS: When I was in grad school at UCLA, Elijah Anderson gave a talk in our department. At one point in the question-and-answer portion he made an off-the-cuff comment that the best sociology is sometimes just documenting how “regular” people—as in, non-sociologists—do sociology in their day to day lives. Whether at work, at home, at church, or on a date, people run into recurring dilemmas and vexing situations. Just like us “licensed” sociologists, they try to figure these things out, collecting data, forming hypotheses, testing hunches, assessing their findings, and implementing the lessons learned. It’s our job, then, to figure out how different people walk though these common phases. This idea really stuck with me and colors how I approach research, writing, and teaching. Maybe the thing I love most is that it encourages us to move from deficit-based approaches to asset-based ones that rethink even the most marginalized groups as creative problem solvers.

https://press.princeton.edu/ideas/office-hours-with-forrest-stuart

1 note

·

View note

Text

oh, hello professor stuart...

What are you reading now?

FS: For the last decade or so, I’ve developed the habit of keeping two books on my bedside table at any given time, reading a bit of both each night as I wind down. The first is typically a newly published ethnography, which helps me stay current in my field. Right now, it’s Policing the Racial Divide: Urban Growth Politics and the Remaking of Segregation, by Daanika Gordon. The book takes us throughout daily life in Rust Belt city via police ride-alongs, community meetings, and other public events. Gordon weaves a fresh analysis of how police departments do more than merely respond to the racialized issues emanating from histories of segregation; rather, they are key, active authors in creating and reproducing the urban color line. As urban sociologists, geographers, and political economists continue to take policing more seriously, this book feels like the first of a new era of much-needed scholarship.

The second book in my bedside rotation is always a fantasy novel. My obsession with the genre is something I’ve kept very quiet around colleagues, until now, I suppose. I’m currently wrapping up the fifth and final book of Brent Weeks’s Lightbringer series. It follows a young orphan challenging an empire ruled by religious authoritarianism, palace intrigue, and, yes, a healthy dose of magic. Weeks’ series is deeply ethnographic, with complex worldbuilding that stretches between the multiple thousand-page books. I’m especially fond of the detailed maps on the first few pages, which let me follow the protagonist’s journey across mountain ranges and oceans. In my first book, Down, Out, and Under Arrest, which documents policing’s ripple effects across everyday life in LA’s Skid Row, I designed and included a map of the neighborhood as a kind of homage to my favorite fantasy writers. I also find myself dog-earing pages of fantasy novels when I spot literary tricks and grammatical moves I hope to try out in my own prose.

What book has had the most impact on your career?

FS: Without a doubt, the book that has had the biggest impact on my career is Mitchell Duneier’s masterful 1999 book, Sidewalk. It’s an ethnography of Black, precariously housed magazine vendors who set up shop on Sixth Avenue in New York’s Greenwich Village. Through Duneier’s fieldwork, we see how the vendors become “eyes on the street” to enhance safety for vulnerable populations, provide mentorship to young Black men in the local service economy, and act as key “nodes” that link residents across racial, class, and generational lines. Throughout his analysis, Duneier “zooms out,” tracing how structural forces, like deindustrialization and zero-tolerance policing, have aligned to bring the vendors to this location and hound their continued existence. He also “zooms in” to the interactional level using conversation analysis (CA), measuring split second pauses and turn-taking to show how vendors’ seemingly innocuous chatter with passersby constitutes a form of “interactional vandalism” that intimidates women and reinforcing stereotypes about Black men. Stylistically, Sidewalk often reads more like a novel, with flowing dialogue punctuated with beautiful black and white photos from the Chicago Tribune’s Ovie Carter.

A few years after its release, Sidewalk was also the subject of arguably the most famous book review symposium in sociology, generating a heated back-and-forth between Duneier and Berkeley’s Loïc Wacquant on the issues of transparency, representation, and the role of urban ethnography in the fetishization of poverty. I return to the debate every time I start a new project.

What is your favorite book to teach?

FS: In just about every class I teach, I look for new ways to put Mary Pattillo’s now-classic Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril among the Black Middle Class on the syllabus. I start by showing students how Pattillo uses the opening “setting” section—often a perfunctory, forgettable part of a book—to set up a wonderful empirical puzzle. Walking the reader through a tour of the “Groveland” neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side, Pattillo paints a scene where, because of intergenerational segregation, middle class Black residents, banks, and churches share walls and sidewalks with low-income Black residents, subsidized housing, and check cashing outlets. How, Pattillo leads us to ask, does this unique cross-class proximity structure everyday life and social organization for the Black middle class? In answering, Pattillo deploys several analytical strategies that I pass on to my students. She shows the underestimated power of creating typologies, finding variation among Groveland residents (for example, whether they internalize or merely perform “street culture”), and then showing how variation along these lines leads to differing outcomes. She also leverages the power of “deviant” cases to show how certain people blur the boundaries of ideal types, forcing us to rethink and refine many of our taken-for-granted theoretical categories. The book is simultaneously a lesson on how to write about participants and their communities, especially those who occupy marginalized social positions. Pattillo’s empathy and respect shine through on every page, from the pseudonyms she chooses to the biographical details she shares (and doesn’t share) with the reader.

Do you have a favorite moment as a researcher, maybe an encounter that unexpectedly changed your way of thinking or the direction of a project?

FS: I’m proud of the fact that I’ve had quite a few occasions where an experience radically reshaped my prior assumptions and the direction of the entire project, usually for the better. One that I won’t ever forget came in the early stages of my research for my second book, Ballad of the Bullet. The book follows a group of young Black men on Chicago’s South Side as they strive for popularity—and an income—in the digital economy. They spent their days recording and uploading a homemade genre of gangsta rap, sometimes referred to as “drill music” to YouTube. Then, they turn to their multiple social media platforms to try to authenticate the hardened criminal personas they crafted in their songs. A music video about committing a drive-by shooting might be accompanied on Twitter with talk of potential victims and Instagram photos holding a gun out of a car window. When done well, it’s easy to start believing that young men in the drill scene might actually do the deeds they rap about. That’s their intention, after all—to lure in voyeuristic, middle-class audiences looking for a glimpse into ghetto life.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I had bought into quite a few of their performances of “badness.” Of course, I knew that they weren’t nearly as violent as they wanted their typical audiences to believe. But when I really got to know them, I learned that the vast majority of their posts weren’t just exaggerations, they were utter fabrications. Some of the men known as the most violent had never actually fired a gun, and even avoided conflict. Focusing instead on these young men’s inauthenticity, and their strategies of performance, let me highlight their savvy creativity amid some incredible structural obstacles.

What is the best career advice you ever received?

FS: When I was in grad school at UCLA, Elijah Anderson gave a talk in our department. At one point in the question-and-answer portion he made an off-the-cuff comment that the best sociology is sometimes just documenting how “regular” people—as in, non-sociologists—do sociology in their day to day lives. Whether at work, at home, at church, or on a date, people run into recurring dilemmas and vexing situations. Just like us “licensed” sociologists, they try to figure these things out, collecting data, forming hypotheses, testing hunches, assessing their findings, and implementing the lessons learned. It’s our job, then, to figure out how different people walk though these common phases. This idea really stuck with me and colors how I approach research, writing, and teaching. Maybe the thing I love most is that it encourages us to move from deficit-based approaches to asset-based ones that rethink even the most marginalized groups as creative problem solvers.

If you could have dinner with two sociologists, living or passed, who would they be and why?

FS: Karl Marx and Erving Goffman. These are the two sociologists that have influenced me the most intellectually and personally. These are, in my opinion, the two most brilliant thinkers in history. But I’ve always felt a tension between the core premises of their work, especially around what explains social life and outcomes. For Marx, the key explanations rest at the macro level of political economy, in the structural relationships between classes. Marx seems hardly concerned with what goes on during micro-level interactions between people. For Goffman, it’s mostly the opposite, privileging interactions and bounded situations while paying much less attention to macro level forces. And yet, when we look out at the world, there’s plenty of evidence that both are “right.” I’d love to pour the two of them a few stiff cocktails and see if we can find the common threads running through their thinking.

0 notes

Text

Les nouveautés de la semaine (17/10/2022)

À la une : La carrière diplomatique en Belgique : guide du candidat au concours / Raoul Delcorde, Michel Liégeois, Fanny Lutz, Claude Roosens et Maureen Walschot

Cote de rangement : JZ 1609 D 265486 / Domaine : Sciences Politiques

"La carrière diplomatique attire, voire fascine, suscitant des centaines de candidats chaque fois que le Service public fédéral Affaires étrangères organise un concours de recrutement. En Belgique. Passé le cap des études qui préparent à cette carrière, reste cependant une épreuve considérée à juste titre comme redoutable : le concours... Lire la suite

La carrière diplomatique attire, voire fascine, suscitant des centaines de candidats chaque fois que le Service public fédéral Affaires étrangères organise un concours de recrutement. en Belgique. Passé le cap des études qui préparent à cette carrière, reste cependant une épreuve considérée à juste titre comme redoutable : le concours organisé par les services de recrutement de l'État fédéral belge. Beaucoup y sont appelés, pour très peu d’élus. Cette hypersélection témoigne des exigences élevées du concours lui-même. Trop souvent, malgré leur passion et leur diplôme, les candidats arrivent au concours insuffisamment préparés, ou ne croient pas assez en leur chance. Ce livre, le premier du genre en Belgique, se propose de les assister dans la bonne préparation des épreuves. Il apporte aussi un éclairage historique sur la « Carrière » et sur l’évolution de la fonction diplomatique. La mise en œuvre du nouveau statut de la carrière extérieure, qui fusionne les carrières diplomatiques, consulaires et d’attachés de coopération et les modifications du processus de recrutement qu’elle entraîne justifiait une révision en profondeur de l’ouvrage. Cette cinquième édition a été entièrement revue et mise à jour." - Quatrième de couverture

-------------------------------------

Gestion

Comportements humains et management / Frédérique Alexandre-Bailly, Denis Bourgeois, Jean-Pierre Gruère e.a.

Cote de rangement : HF 5549 .5.C6 C 265496

Energy and motivation / Harvard Business Review

Cote de rangement : HF 5549 .5.M63 E 265499

-------------------------------------

Économie

Citoyen du monde : mémoires / Amartya Sen

Cote de rangement : HB 126 .I43 S 265497

Why the west is failing : failed economics and the rise of the east / John Mills

Cote de rangement : HD 82 M 265507

-------------------------------------

Sciences politiques

The culture of democracy : a sociological approach to civil society / Bin Xu

Cote de rangement : JC 337 X 265502

Sur la légitimité : croyance, obéissance, résistance / Yves Mény

Cote de rangement : JC 497 M 265493

Blue labour : the politics of the common good / Maurice Glasman

Cote de rangement : JN 1129 .L32 G 265500

Rural democracy : elections and development in Africa / Robin Harding

Cote de rangement : JQ 1879 .A15 H 265506

-------------------------------------

Finance

L'alchimie de la finance / George Soros

Cote de rangement : HG 4515 S 265498

-------------------------------------

Éducation

Les stratégies d'apprentissage : comment accompagner les élèves dans l'appropriation des savoirs / Michel Perraudeau

Cote de rangement : LB 1060 P 265490

Panique à l'université : rectitude politique, wokes et autres menaces imaginaires / Francis Dupuis-Déri

Cote de rangement : LC 191 .9 D 265489

-------------------------------------

Sociologie

Sociologie des émotions / sous la direction de Nathalie Burnay

Cote de rangement : BF 531 S 265487

Voyage au pays des boxeurs / textes et photographies de Loïc Wacquant

Cote de rangement : GV 1125 W 265491

Par-delà l'androcène / Adélaïde Bon, Sandrine Roudaut, Sandrine Rousseau

Cote de rangement : HM 821 B 265488

Facial recognition / Mark Andrejevic, Neil Selwyn

Cote de rangement : HM 851 A 265503

Que fait la police ? et comment s'en passer / Paul Rocher

Cote de rangement : HV 8203 R 265484

Dans la tête des black blocs : vérités et idées reçues / Thierry Vincent

Cote de rangement : HX 833 V 265485

-------------------------------------

Histoire

Prodiges et vertiges de l'analogie : de l'abus des belles-lettres dans la pensée / Jacques Bouveresse

Cote de rangement : DC 33 .7 B 265492

-------------------------------------

Communication

A history of lying / Juan Jacinto Muñoz-Renge

Cote de rangement : BJ 1425 M 265504

Media and events in history / Espen Ytreberg

Cote de rangement : P 96 .H55 Y 265505

-------------------------------------

Arts

Spectatrices ! : de l'Antiquité à nos jours / sous la direction de Véronique Lochert, Marie Bouhaïk-Gironès, Céline Candiard, Fabien Cavaillé, Jeanne-Marie Hostiou, Mélanie Traversier

Cote de rangement : PN 1590 .A9 S 265495

La revanche des autrices : enquête sur l'invisibilisation des femmes en littérature / Julien Marsay

Cote de rangement : PQ 149 M 265494

-------------------------------------

Santé

Covid-19 : the postgenomic pandemic / Hugh Pennington

Cote de rangement : RA 644 .C67 P 265501

-------------------------------------------------------------

Tous ces ouvrages sont exposés sur le présentoir des nouveautés de la BSPO. Ceux-ci pourront être empruntés à domicile à partir du 31 octobre 2022.

0 notes

Text

William julius wilson the truly disadvantaged pdf

WILLIAM JULIUS WILSON THE TRULY DISADVANTAGED PDF >>Download (Herunterladen)

vk.cc/c7jKeU

WILLIAM JULIUS WILSON THE TRULY DISADVANTAGED PDF >> Online Lesen

bit.do/fSmfG

In this punchy book, Loïc Wacquant retraces the invention and metamorphoses of this racialized folk devil, from the structural conception of Swedish economist3 Entzivilisieren und Dämonisieren. Die soziale - De Gruyterdegruyter.com › document › doi › pdfdegruyter.com › document › doi › pdffechter der „Diskongruenz“-Hypothese, etwa William Julius Wilson und wissenschaftliche Bücher wie The Truly Disadvantaged von William. Julius Wilson von M Merten · 2017 · Zitiert von: 1 — William Julius Wilson: The Truly Disadvantaged. Moritz Merten. Chapter; First Online: 13 August 2016. München: Academic, S. 227-236 VV Städtebauförderung 2010 (pdf-download): Zugriff am 05.05.2009 Wilson, William Julius (1987). The Truly Disadvantaged. 05.07.2022 — William Julius Wilson: The Truly Disadvantaged To read the full-text of this research, you can request a copy directly from the author. 15.10.2019 — William Julius Wilson 2009: More than Just Race: Being Black and Poor in the Inner William Julius Wilson: The Truly Disadvantaged. Gunnar Myrdal to the behavioral notion of Washington think-tank experts to the neo-ecological formulation of sociologist William Julius Wilson. von M Merten · 2017 · Zitiert von: 1 — Öffnen. MertenWilliamJuliusWilsonManuskript.pdf (740.3Kb) (William Julius Wilson: Die räumliche und soziale Isolation der Unterklasse)

https://www.tumblr.com/poxumahafuka/698181218667216896/leipzig-karte-pdf-files, https://www.tumblr.com/poxumahafuka/698184660789936129/analogia-fidei-hermeneutics-pdf, https://www.tumblr.com/poxumahafuka/698184817848795136/1999-bass-tracker-pro-team-175-owners-handbuch, https://www.tumblr.com/poxumahafuka/698184660789936129/analogia-fidei-hermeneutics-pdf, https://www.tumblr.com/poxumahafuka/698184817848795136/1999-bass-tracker-pro-team-175-owners-handbuch.

0 notes

Text

Explain the researcher’s role in qualitative research in general and specifically in an ethnographic approach.

Explain the researcher’s role in qualitative research in general and specifically in an ethnographic approach.

In your paper, you will present the benefits of ethnographical research in terms of understanding a unique social world, as well as understanding the qualitative researcher’s role in performing and reporting on ethnographic research. You will do this through the resources provided, your own research of immersive ethnographical approaches, and also through critiquing Dr. Loïc Wacquant’s work.

In…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The street and the ring

The street and the ring

Loïc Wacquant offers a fascinating piece of urban ethnography in Body & Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer. It is his account of his three-year experience while a sociology graduate student at the University of Chicago of participating in the Woodlawn Boys and Girls Club, a boxing club for young men who are serious about the sport of boxing on the South Side of Chicago. Wacquant takes the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

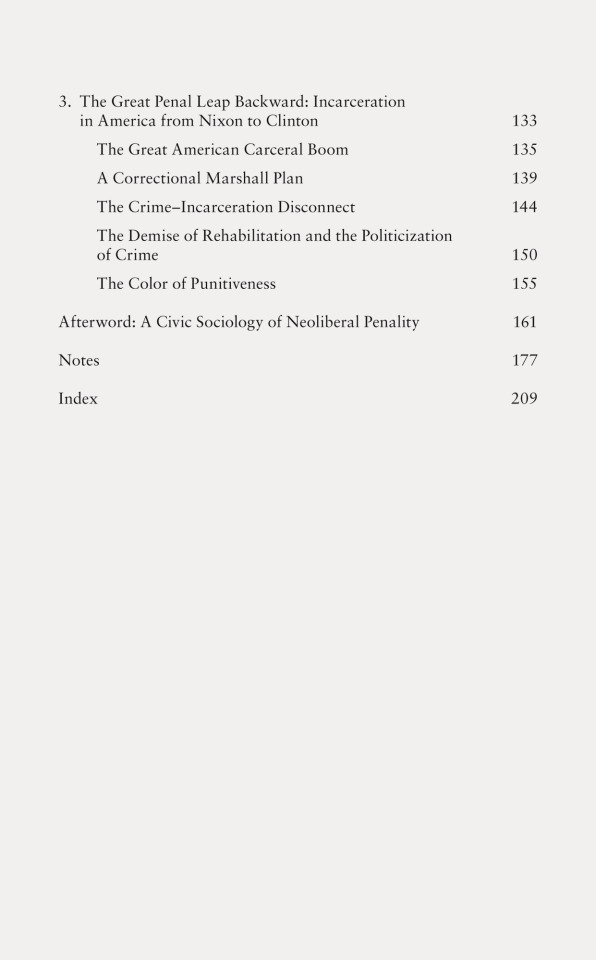

Loïc J. D. Wacquant, (1999), Prisons of Poverty, Contradictions Series, Volume 23, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN, and London, 2009, Expanded Edition

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

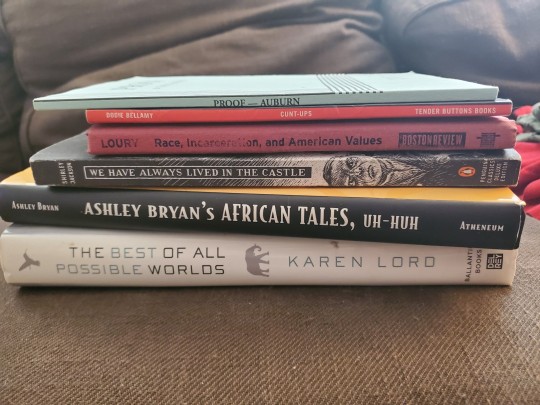

My mom brought me some boxes of books from home and I pulled out some rereads I want to do soon.

Can you tell I've never been able to hone in my interests?

[Books in picture:

Proof David Auburn

Cunt-Ups Dodie Bellamy

Race, Incarceration, and American Values Glenn C. Loury (with Pamela S. Karlan, Tommie Shelby, and Loïc Wacquant)

We Have Always Lived In The Castle Shirley Jackson

Ashley Bryan's African Tales, Uh-Huh

The Best Of All Possible Worlds Karen Lord]

#im about to take a bath#so its probs gonna be either lord or jackson i start with#books#my books#im only partly through a first read of African tales#but it's both gorgeous and fun

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

In his review, Sexton filters much of his review through Wilderson’s application of psychoanalytic theory, though there are several ways to organize Afro-pessimist thought. My own treatment of the field is reflective of different ongoing threads of influence and theoretical emphases. As indicated above, one thread of Afro-pessimism reflects a strong intellectual heritage from Lacanian psycho-analysis (Lacan and Fink 2002), by way of Fanon (1952), in the works of Wilderson (2010) and Hartman (1997). Another thread is rooted at the nexus of race and biopolitics. In this vein, Sexton (2011) has fruitfully critiqued the work of Giorgio Agamben (1998) and also incorporated lessons from Patterson (1982) to build insightful commentary on contemporary racial politics and institutions surrounding black people. There is also a strong influence from, and critique of, recent Marxist theorizing in the works of Agathangelou (2010), Sabine Broeck (2016), Daniel Barber (2016), and Wilderson (2003a, 2003b). Finally, scholars focusing on historical approaches tend to argue that slavery, specifically in the Americas, forms a distinct starting point for understanding contemporary racial politics. This argument is apparent in the works of several key thinkers, such as Hartman (2008), Vincent Brown (2009), Katherine McKittrick (Hudson and McKittrick 2014), and even Loïc Wacquant (2002) (Carico 2016). Their historical approach is matched with a parallel analysis of African colonialism. It is useful to recall that Fanon and also Achille Mbembe (2008), whose works are frequently cited in Afro-pessimist literature, directly theorize the racial impacts of such colonialism as distinct from slavery in the Americas. I highlight just a few of these differences within Afro-pessimism to emphasize the diversity of thought within the approach as well as to outline the breadth of the field and its relevance to different aspects of sociological work at the nexus of race, institutions, political economy, and history.

George Weddington - Political Ontology and Race Research: A Response to “Critical Race Theory, Afro-pessimism, and Racial Progress Narratives” (2018) [Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 1–11, American Sociological Association]

#afropessimism#political ontology#disciplines#jared sexton#frank wilderson#psychoanalysis#biopolitics#marxism#colonialism#neocolonialism#critical race theory#racial progress

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Contra la ampliación de la miseria en los barrios condenados

Las primeras familias impactadas por la expulsión de trabajadores y trabajadoras del mercado laboral en la Gran Recesión económica que comenzó en 2008 fueron las de los barrios vulnerables. Hoy, no han salido de aquella, y en su doble confinamiento, por un lado, en sus precarias viviendas, y por el otro, en el cotidiano encierro social en su barrio, se preguntan, por qué otra vez.

Así, desde el interior de sus casas, ven en televisión cómo miles de coches salen de grandes ciudades camino a sus segundas viviendas en la costa; escuchan recomendaciones para que los niños sigan sus tareas desde un ordenador conectado a Internet; escuchan los beneficios de la lectura y la práctica de las artes; de la posibilidad de seguir tutoriales para hacer deporte en casa, u otras muchas cosas para las que nunca se tiene tiempo, para poder sobrellevar el confinamiento. Si el virus aparenta igualar, su impacto económico y social demarca claramente las clases sociales.

Sin embargo, y pese al desasosiego de la pérdida de parte de los pocos ingresos que tiene el hogar, las noticias les hacen por una vez imaginar y sentir a algunas familias que forman parte de una práctica colectiva generalizada y responsable: quedarse confinados en casa. Cuidan y son cuidados.

Las relaciones entre el espacio físico y el espacio social se pueden observar en la estructuración de nuestras ciudades. La ciudad puede leerse como un mapa en el cual la apropiación jerarquizada del espacio diferencia con un marcado contraste entre los barrios y urbanizaciones residenciales y los barrios vulnerables y estigmatizados social y territorialmente. Así queda dibujada la desigualdad en la distribución de los bienes, los recursos, las vigilancias y las penas. Esa distancia social ha sido construida y es impuesta históricamente en estos lugares condenados, -no es natural, parafraseando a Pierre Bourdieu sobre “los efectos del lugar”-, abocando a los habitantes de estos barrios (clase obrera desproletarizada en caída libre, poblaciones de minorías étnicas -en España, una parte del pueblo gitano- y de inmigrantes), a economías hiperprecarias de subsistencia e informalidad; a servicios colectivos disminuidos y de baja calidad (donde los hay); en los que las tasas de desempleo o de fracaso escolar duplican las del resto de la población; donde se exacerban las medidas de control y vigilancia de los comportamientos (los Servicios Sociales y la policía conocen al milímetro las vidas de las poblaciones de estos barrios y los centros de menores son considerados parte de la socialización ineludible de buena parte de los jóvenes por muchas de las familias); y donde la vida colectiva y la reivindicación sociopolítica de estos barrios ha desaparecido por completo.

Esta dinámica estigmatizante de miseria y descrédito social y territorial se refuerza cuando la víctima se comporta reaccionando como lo prefija el relato de ese estigma.

Y no sólo desde la política, desde las instituciones públicas o desde los medios de comunicación se va a conformar esa depreciación material y simbólica de estos barrios y de la población que los habita, sino también desde los propios vecinos, que van a interiorizar esos discursos discriminatorios contra sus iguales en un intento de distinción que desea diluir la propia situación de desamparo social. Así lo describía la mirada sociológica de Benito Pérez Galdós en referencia al Madrid de 1897 cuando observaba que: “Como en toda región del mundo hay clases, sin que se exceptúen de esta división capital las más ínfimas jerarquías, allí no eran todos los pobres lo mismo”.

El sociólogo francés Loïc Wacquant ha analizado comparativamente durante años la estructura de relegación urbana de los guetos estadounidenses y las banlieues francesas. Entre sus conclusiones, señala que estos barrios comparten entre ellos varias características, a saber: que son territorios delimitados y segregados, en los que habita población etiquetada negativamente. Sin embargo, y más importante, es la diferencia que matiza en torno a lo público. Así, observa que en los guetos americanos, el Estado ha desaparecido en todas sus formas, obligando a generar instituciones paralelas, subsidiarias y precarias en el interior de los barrios (Esto ya se prevé un elemento diferenciador en el impacto del Covid-19 en EE.UU.). En Europa, si bien las instituciones públicas han disminuido su presencia y calidad de los servicios públicos (más aún las organizaciones de representación y las de la sociedad civil), en los barrios -con excepciones- las instituciones públicas están presentes, sobre todo las sanitarias, las educativas, los servicios sociales y la policía. (El comportamiento en estos barrios ha sido ejemplar en nuestro país durante lo que llevamos de Estado de Alarma -aviso a navegantes: señalar las excepciones es reduccionista y discriminatorio-).

Esa es nuestra fuerza colectiva también en los barrios vulnerables de nuestras ciudades: lo público. Aquí hay que tener claro que tiene que ser lo político el lugar desde donde hay que empezar a dar pasos claros y contundentes ante el desastre social que se avecina, y ante el histórico olvido y desamparo ofrecido hasta ahora por gobiernos de todo color (los directivos de las fuerzas de seguridad del Estado, pueden guardar su profecía de que puede haber estallidos de violencia –como han dicho- y empujar para activar el colchón económico-social necesario antes de que aquella se cumpla). Desde los años 90’ del siglo pasado sabemos que la solución no pasa sólo por las políticas sociales de empleo, por lo que ya hay que actuar claramente, como se viene proponiendo desde entonces, en la provisión de un derecho de subsistencia basado en una renta básica digna.

Y si de la política se trata hemos de reconocer que el actual gobierno, en la segunda semana del Estado de Alarma, envió un documento técnico[1] dirigido a las autoridades políticas regionales y locales, y a los Servicios Sociales de todo el país, con recomendaciones y medidas concretas para comenzar a abordar este grave problema. Es así ésta, toda una expresión de voluntad política necesaria para empezar a luchar contra la ampliación – y por la erradicación- de la miseria en los barrios condenados.

[1] El documento técnico elaborado por la Secretaría de Estado de Derechos Sociales se denomina: “Documento técnico de recomendaciones de actuación de los Servicios Sociales ante la crisis por Covid-19, en asentamientos segregados y barrios altamente vulnerables”.

Publicado por Miguel Ángel Alzamora Domínguez.

Profesor de Sociología en la Universidad de Murcia.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Against Innocence Race, Gender, and the politics of Safety

Saidiya V. Hartman: I think that gets at one of the fundamental ethical questions/problems/crises for the West: the status of difference and the status of the other. It’s as though in order to come to any recognition of common humanity, the other must be assimilated, meaning in this case, utterly displaced and effaced: “Only if I can see myself in that position can I understand the crisis of that position.” That is the logic of the moral and political discourses we see every day — the need for the innocent black subject to be victimized by a racist state in order to see the racism of the racist state. You have to be exemplary in your goodness, as opposed to ...

Frank Wilderson: [laughter] A nigga on the warpath!

While I was reading the local newspaper I came across a story that caught my attention. The article was about a 17 year-old boy from Baltimore named Isaiah Simmons who died in a juvenile facility in 2007 when five to seven counselors suffocated him while restraining him for hours. After he stopped responding they dumped his body in the snow and did not call for medical assistance for over 40 minutes. In late March 2012, the case was thrown out completely and none of the counselors involved in his murder were charged with anything. The article I found online about the case was titled “Charges Dropped Against 5 In Juvenile Offender’s Death.” By emphasizing that it was a juvenile offender who died, the article is quick to flag Isaiah as a criminal, as if to signal to readers that his death is not worthy of sympathy or being taken up by civil rights activists. Every comment left on the article was crude and contemptuous — the general sentiment was that his death was no big loss to society. The news about the case being thrown out barely registered at all. There was no public outcry, no call to action, no discussion of the many issues bound up with the case — youth incarceration, racism, the privatization of prisons and jails (he died at a private facility), medical neglect, state violence, and so forth — though to be fair, there was a critical response when the case initially broke.

For weeks after reading the article I kept contemplating the question: What is the difference between Trayvon Martin and Isaiah Simmons? Which cases galvanize activists into action, and which are ignored completely? In the wake of the Jena 6, Troy Davis, Oscar Grant, Trayvon Martin, and other high profile cases,1 I have taken note of the patterns that structure political appeals, particularly the way innocence becomes a necessary precondition for the launching of anti-racist political campaigns. These campaigns often center on prosecuting and harshly punishing the individuals responsible for overt and locatable acts of racist violence, thus positioning the State and the criminal justice system as an ally and protector of the oppressed. If the “innocence” of a Black victim is not established, he or she will not become a suitable spokesperson for the cause. If you are Black, have a drug felony, and are attempting to file a complaint with the ACLU regarding habitual police harassment — you are probably not going to be legally represented by them or any other civil rights organization anytime soon.2 An empathetic structure of feeling based on appeals to innocence has come to ground contemporary anti-racist politics. Within this framework, empathy can only be established when a person meets the standards of authentic victimhood and moral purity, which requires Black people, in the words of Frank Wilderson, to be shaken free of “niggerization.” Social, political, cultural, and legal recognition only happens when a person is thoroughly whitewashed, neutralized, and made unthreatening. The “spokesperson” model of doing activism (isolating specific exemplary cases) also tends to emphasize the individual, rather than the collective nature of the injury. Framing oppression in terms of individual actors is a liberal tactic that dismantles collective responses to oppression and diverts attention from the larger picture.

Using “innocence” as the foundation to address anti-Black violence is an appeal to the white imaginary, though these arguments are certainly made by people of color as well. Relying on this framework re-entrenches a logic that criminalizes race and constructs subjects as docile. A liberal politics of recognition can only reproduce a guilt-innocence schematization that fails to grapple with the fact that there is an a priori association of Blackness with guilt (criminality). Perhaps association is too generous — there is a flat-out conflation of the terms. As Frank Wilderson noted in “Gramsci’s Black Marx,” the cop’s answer to the Black subject’s question — why did you shoot me? — follows a tautology: “I shot you because you are Black; you are Black because I shot you.”3 In the words of Fanon, the cause is the consequence.4 Not only are Black men assumed guilty until proven innocent, Blackness itself is considered synonymous with guilt. Authentic victimhood, passivity, moral purity, and the adoption of a whitewashed position are necessary for recognition in the eyes of the State. Wilderson, quoting N.W.A, notes that “a nigga on the warpath” cannot be a proper subject of empathy.5 The desire for recognition compels us to be allies with, rather than enemies of the State, to sacrifice ourselves in order to meet the standards of victimhood, to throw our bodies into traffic to prove that the car will hit us rather than calling for the execution of all motorists. This is also the logic of rape revenge narratives — only after a woman is thoroughly degraded can we begin to tolerate her rage (but outside of films and books, violent women are not tolerated even when they have the “moral” grounds to fight back, as exemplified by the high rates of women who are imprisoned or sentenced to death for murdering or assaulting abusive partners).

We may fall back on such appeals for strategic reasons — to win a case or to get the public on our side — but there is a problem when our strategies reinforce a framework in which revolutionary and insurgent politics are unimaginable. I also want to argue that a politics founded on appeals to innocence is anachronistic because it does not address the transformation and re-organization of racist strategies in the post-civil rights era. A politics of innocence is only capable of acknowledging examples of direct, individualized acts of racist violence while obscuring the racism of a putatively colorblind liberalism that operates on a structural level. Posing the issue in terms of personal prejudice feeds the fallacy of racism as an individual intention, feeling or personal prejudice, though there is certain a psychological and affective dimension of racism that exceeds the individual in that it is shaped by social norms and media representations. The liberal colorblind paradigm of racism submerges race beneath the “commonsense” logic of crime and punishment. This effectively conceals racism, because it is not considered racist to be against crime. Cases like the execution of Troy Davis, where the courts come under scrutiny for racial bias, also legitimize state violence by treating such cases as exceptional. The political response to the murder of Troy Davis does not challenge the assumption that communities need to clean up their streets by rounding up criminals, for it relies on the claim that Davis is not one of those feared criminals, but an innocent Black man. Innocence, however, is just code for nonthreatening to white civil society. Troy Davis is differentiated from other Black men — the bad ones — and the legal system is diagnosed as being infected with racism, masking the fact that the legal system is the constituent mechanism through which racial violence is carried out (wishful last-minute appeals to the right to a fair trial reveal this — as if trials were ever intended to be fair!). The State is imagined to be deviating from its intended role as protector of the people, rather than being the primary perpetrator. H. Rap Brown provides a sobering reminder that, “Justice means ‘just-us-white-folks.’ There is no redress of grievance for Blacks in this country.”6

While there are countless examples of overt racism, Black social (and physical) death is primarily achieved via a coded discourse of “criminality” and a mediated forms of state violence carried out by a impersonal carceral apparatus (the matrix of police, prisons, the legal system, prosecutors, parole boards, prison guards, probation officers, etc). In other words — incidents where a biased individual fucks with or murders a person of color can be identified as racism to “conscientious persons,” but the racism underlying the systematic imprisonment of Black Americans under the pretense of the War on Drugs is more difficult to locate and generally remains invisible because it is spatially confined. When it is visible, it fails to arouse public sympathy, even among the Black leadership. As Loïc Wacquant, scholar of the carceral state, asks, “What is the chance that white Americans will identify with Black convicts when even the Black leadership has turned its back on them?”7 The abandonment of Black convicts by civil rights organizations is reflected in the history of these organizations. From 1975-86, the NAACP and the Urban League identified imprisonment as a central issue, and the disproportionate incarceration of Black Americans was understood as a problem that was structural and political. Spokespersons from the civil rights organizations related imprisonment to the general confinement of Black Americans. Imprisoned Black men were, as Wacquant notes, portrayed inclusively as “brothers, uncles, neighbors, friends.”8 Between 1986-90 there was a dramatic shift in the rhetoric and official policy of the NAACP and the Urban League that is exemplary of the turn to a politics of innocence. By the early 1990s, the NAACP had dissolved its prison program and stopped publishing articles about rehabilitation and post-imprisonment issues. Meanwhile these organizations began to embrace the rhetoric of individual responsibility and a tough-on-crime stance that encouraged Blacks to collaborate with police to get drugs out of their neighborhoods, even going as far as endorsing harsher sentences for minors and recidivists.

Black convicts, initially a part of the “we” articulated by civil rights groups, became them. Wacquant writes, “This reticence [to advocate for Black convicts] is further reinforced by the fact, noted long ago by W.E.B. DuBois, that the tenuous position of the black bourgeoisie in the socioracial hierarchy rests critically on its ability to distance itself from its unruly lower-class brethren: to offset the symbolic disability of blackness, middle-class African Americans must forcefully communicate to whites that they have ‘absolutely no sympathy and no known connections with any black man who has committed a crime.’”9 When the Black leadership and middle-class Blacks differentiate themselves from poorer Blacks, they feed into a notion of Black exceptionalism that is used to dismantle anti-racist struggles. This class of exceptional Blacks (Barack Obama, Condoleeza Rice, Colin Powell) supports the collective delusion of a post-race society.

The shift in the rhetoric and policy of civil rights organizations is perhaps rooted in a fear of affirming the conflation of Blackness and criminality by advocating for prisoners. However, not only have these organizations abandoned Black prisoners — they shore up and extend the Penal State by individualizing, depoliticizing, and decontextualizing the issue of “crime and punishment” and vilifying those most likely to be subjected to racialized state violence. The dis-identification with poor, urban Black Americans is not limited to Black men, but also Black women who are vilified via the figure of the Welfare Queen: a lazy, sexually irresponsible burden on society (particularly hard-working white Americans). The Welfare State and the Penal State complement one another, as Clinton’s 1998 statements denouncing prisoners and ex-prisoners who receive welfare or social security reveal: he condemns former prisoners receiving welfare assistance for deviously committing “fraud and abuse” against “working families” who “play by the rules.”10 Furthermore, this complementarity is gendered. Black women are the shock absorbers of the social crisis created by the Penal State: the incarceration of Black men profoundly increases the burden put on Black women, who are force to perform more waged and unwaged (caring) labor, raise children alone, and are punished by the State when their husbands or family members are convicted of crimes (for example, a family cannot receive housing assistance if someone in the household has been convicted of a drug felony). The re-configuration of the Welfare State under the Clinton Administration (which imposed stricter regulations on welfare recipients) further intensified the backlash against poor Black women. On this view, the Welfare State is the apparatus used to regulate poor Black women who are not subjected to regulation, directed chiefly at Black men, by the Penal State — though it is important to note that the feminization of poverty and the punitive turn in non-violent crime policy led to an 400% increase in the female prison population between 1980 and the late 1990s.11 Racialized patterns of incarceration and the assault on the urban poor are not seen as a form of racist state violence because, in the eyes of the public, convicts (along with their families and associates) deserve such treatment. The politics of innocence directly fosters this culture of vilification, even when it is used by civil rights organizations.

WHITE SPACE

[C]rime porn often presents a view of prisons and urban ghettoes as “alternate universes” where the social order is drastically different, and the links between social structures and the production of these environments is conveniently ignored. In particular, although they are public institutions, prisons are removed from everyday US experience.12

The spatial politics of safety organizes the urban landscape. Bodies that arouse feelings of fear, disgust, rage, guilt, or even discomfort must be made disposable and targeted for removal in order to secure a sense of safety for whites. In other words, the space that white people occupy must be cleansed. The visibility of poor Black bodies (as well as certain non-Black POC, trans people, homeless people, differently-abled people, and so forth) induces anxiety, so these bodies must be contained, controlled, and removed. Prisons and urban ghettoes prevent Black and brown bodies from contaminating white space. Historically, appeals to the safety of women have sanctioned the expansion of the police and prison regimes while conjuring the racist image of the Black male rapist. With the rise of the Women’s Liberation Movement in the 1970s came an increase in public awareness about sexual violence. Self-defense manuals and classes, as well as Take Back the Night marches and rallies, rapidly spread across the country. The 1970s and 1980s saw a surge in public campaigns targeted at women in urban areas warning of the dangers of appearing in public spaces alone. The New York City rape squad declared that “[s]ingle women should avoid being alone in any part of the city, at any time.”13 In The Rational Woman’s Guide to Self-Defense (1975), women were told, “a little paranoia is really good for every woman.”14 At the same time that the State was asserting itself as the protector of (white) women, the US saw the massive expansion of prisons and the criminalization of Blackness. It could be argued that the State and the media opportunistically seized on the energy of the feminist movement and appropriated feminist rhetoric to establish the racialized Penal State while simultaneously controlling the movement of women (by promoting the idea that public space was inherently threatening to women). People of this perspective might hold that the media frenzy about the safety of women was a backlash to the gains made by the feminist movement that sought to discipline women and promote the idea that, as Georgina Hickey wrote, “individual women were ultimately responsible for what happened to them in public space.”15 However, in In an Abusive State: How Neoliberalism Appropriated the Feminist Movement Against Sexual Violence, Kristin Bumiller argues that the feminist movement was actually “a partner in the unforeseen growth of a criminalized society”: by insisting on “aggressive sex crime prosecution and activism,” feminists assisted in the creation of a tough-on-crime model of policing and punishment.16

Regardless of what perspective we agree with, the alignment of racialized incarceration and the proliferation of campaigns warning women about the dangers of the lurking rapist was not a coincidence. If the safety of women was a genuine concern, the campaigns would not have been focused on anonymous rapes in public spaces, since statistically it is more common for a woman to be raped by someone she knows. Instead, women’s safety provided a convenient pretext for the escalation of the Penal State, which was needed to regulate and dispose of certain surplus populations (mostly poor Blacks) before they became a threat to the US social order. For Wacquant, this new regime of racialized social control became necessary after the crisis of the urban ghetto (provoked by the massive loss of jobs and resources attending deindustrialization) and the looming threat of Black radical movements.17 The torrent of uprisings that took place in Black ghettoes between 1963-1968, particularly following the murder of Martin Luther King in 1968, were followed by a wave of prison upheavals (including Attica, Solidad, San Quentin, and facilities across Michigan, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Illinois, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania). Of course, these upheavals were easier to contain and shield from public view because they were cloaked and muffled by the walls of the penitentiary.

The engineering and management of urban space also demarcates the limits of our political imagination by determining which narratives and experiences are even thinkable. The media construction of urban ghettoes and prisons as “alternate universes” marks them as zones of unintelligibility, faraway places that are removed from the everyday white experience. Native American reservations are another example of a “void” zone that white people can only access through the fantasy of media representations. What happens in these zones of abjection and vulnerability does not typically register in the white imaginary. In the instance that an “injustice” does register, it will have to be translated into more comprehensible terms.

When I think of the public responses to Oscar Grant and Trayvon Martin, it seems significant that these murders took place in spaces that the white imaginary has access to, which allows white people to narrativize the incidents in terms that are familiar to them. Trayvon was gunned down while visiting family in a gated neighborhood; Oscar was murdered by a police officer in an Oakland commuter rail station. These spaces are not “alternate universes” or void-zones that lie outside white experience and comprehension. To what extent is the attention these cases have received attributable to the encroachment of violence on spaces that white people occupy? What about cases of racialized violence that occur outside white comfort zones? When describing the spatialization of settler colonies, Frantz Fanon writes about “a zone of non-being, an extraordinary sterile and arid region,” where “Black is not a man.”18 In the regions where Black is not man, there is no story to be told. Or rather, there are no subjects seen as worthy of having a story of their own.

TRANSLATION

When an instance of racist violence takes place on white turf, as in the cases of Trayvon Martin and Oscar Grant, there is still the problem of translation. I contend that the politics of innocence renders such violence comprehensible only if one is capable of seeing themselves in that position. This framework often requires that a white narrative (posed as the neutral, universal perspective) be grafted onto the incidents that conflict with this narrative. I was baffled when a call for a protest march for Trayvon Martin made on the Occupy Baltimore website said, “The case of Trayvon Martin – is symbolic of the war on youth in general and the devaluing of young people everywhere.” I doubt George Zimmerman was thinking, I gotta shoot that boy because he’s young! No mention of race or anti-Blackness could be found in the statement; race had been translated to youth, a condition that white people can imaginatively access. At the march, speakers declared that the case of “Trayvon Martin is not a race issue — it’s a 99% issue!” As Saidiya Hartman has asserted in a conversation with Frank Wilderson, “the other must be assimilated, meaning in this case, utterly displaced and effaced.”19

In late 2011, riots exploded across London and the UK after Mark Duggan, a Black man, was murdered by the police. Many leftist and liberals were unable to grapple with the unruly expression of rage among largely poor and unemployed people of color, and refused to support the passionate outburst they saw as disorderly and delinquent. Even leftists fell into the trap of framing the State and property owners (including small business owners) as victims while criticizing rioters for being politically incoherent and opportunistic. Slavoj Žižek, for instance, responded by dismissing the riots as a “meaningless outburst” in an article cynically titled “Shoplifters of the World Unite.” Well-meaning leftists who felt obligated to affirm the riots often did so by imposing a narrative of political consciousness and coherence onto the amorphous eruption, sometimes recasting the participants as “the proletariat” (an unemployed person is just a worker without a job, I was once told) or dissatisfied consumers whose acts of theft and looting shed light on capitalist ideology.20 These leftists were quick to purge and re-articulate the anti-social and delinquent elements of the riots rather than integrate them into their analysis, insisting on figuring the rioter-subject as “a sovereign deliberate consciousness,” to borrow a phrase from Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.21

Following the 1992 LA riots,22 leftist commentators often opted to define the event as a rebellion rather than a riot as a way to highlight the political nature of people’s actions. This attempt to reframe the public discourse is borne of “good intentions” (the desire to combat the conservative media’s portrayal of the riots as “pure criminality”), but it also reflects the an impulse to contain, consolidate, appropriate, and accommodate events that do not fit political models grounded in white, Euro-American traditions. When the mainstream media portrays social disruptions as apolitical, criminal, and devoid of meaning, leftists often respond by describing them as politically reasoned. Here, the confluence of political and anti-social tendencies in a riot/rebellion are neither recognized nor embraced. Certainly some who participated in the London riots were armed with sharp analyses of structural violence and explicitly political messages — the rioters were obviously not politically or demographically homogenous. However, sympathetic radicals tend to privilege the voices of those who are educated and politically astute, rather than listening to those who know viscerally that they are fucked and act without first seeking moral approval. Some leftists and radicals were reluctant to affirm the purely disruptive perspectives, like those expressed by a woman from Hackney, London who said, “We’re not all gathering together for a cause, we’re running down Foot Locker.”23 Or the excitement of two girls stopped by the BBC while drinking looted wine. When asked what they were doing, they spoke of the giddy “madness” of it all, the “good fun” they were having, and said that they were showing the police and the rich that “we can do what we want.”24 Translating riots into morally palatable terms is another manifestation of the appeal to innocence — rioters, looters, criminals, thieves, and disruptors are not proper victims and hence, not legitimate political actors. Morally ennobled victimization has become the necessary precondition for determining which grievances we are willing to acknowledge and authorize.