Text

Self Reflection

The romantic in me is pleasantly surprised to see that “Love” is my most frequent hashtag, even though I’ve dealt with mostly problematic forms of love in my commonplace book. Oh, well. Beggars can’t be choosers--and I thought my number one tag would be “Sexism.” I went into the course thinking that every Renaissance text would be horrifically sexist, and there was definitely a lot of that for it to be my second tag. But the love poetry of Thomas Wyatt comes to mind as a particularly eloquent and touching expression of love even in the face of rejection. Given “Paradise Lost” and New Atlantis, I’m not shocked to see that “Religion” had four uses.

I am, however, shocked to see so many tags regarding the concepts of freedom and free will. They remind me a lot of my Rand Paul Dystopia class where every third word was “freedom.” This index helped me visualize how important the idea of breaking restraints were to the Renaissance writers, and how this had to have been a prelude to the Enlightenment. Lastly, though I only tagged my entry on “Blazing World” as “Homoeroticism,” I’m surprised that we covered even ONE Renaissance text with illusions to queerness. In the end, I did notice that I was overall drawn to themes of romance and the good (and dreadful) ways in which these writers presented relationships.

I truly enjoyed the texts we read this semester, and I’m surprisingly sad to end my commonplace book. Goodbye for now!

0 notes

Text

Index

Actual Truth: page 1

Beauty: page 9

Creepy: page 6

Dystopia: page 6

Equality: pages 4, 5, 10

Feminism: pages 3, 4, 5

Freedom: page 2

Free Will: pages 2, 5

Friendship: page 7

Gender Roles: pages 4, 8

Homoeroticism: page 7

Imagination: page 7

Knowledge: page 1

Labor: page 10

Love: pages 3, 5, 7, 8, 9

Male Gaze: page 9

Misogyny: page 4

Patriarchy: page 4

Positivity: page 3

Purity: page 4

Questioning: page 1

Rejection: page 5

Religion: pages 6, 8, 9, 10

Respect: pages 3, 5

Sexism: pages 4, 8, 9, 10

Utopia: pages 2, 6

Weakness: page 9

Work: page 10

0 notes

Text

Folger Extra Credit Visit

I went to the Folger woodcut exhibit on March 23rd but am only writing about it now because I’m Constantly Tired and Constantly Procrastinating.

(I’m Constantly Stupid.)

I enjoyed how intimate they made such a large space feel. The best part of my visit was the completely full kiddie table, where little ones used stamps to create their own “woodcuts.” I think it was a field trip because a group of harassed adults watched over the children and prevented them from running into a glass case. (I routinely forget to breathe whenever I’m in the vicinity of the rare books, so I can’t imagine SMASHING AN EXHIBIT AT THE FOLGER.) The most exciting part of my visit was, however, meeting one of my rare book’s cousin! I found a text printed by Elzevir in the early seventeenth century. While I could not see the cover, I noticed that the title page is more elaborate than mine; I believe it to be a Biblical or history text geared toward a larger audience given the fancier illustration, but I couldn’t find any information beyond the publisher, author, and year.

0 notes

Text

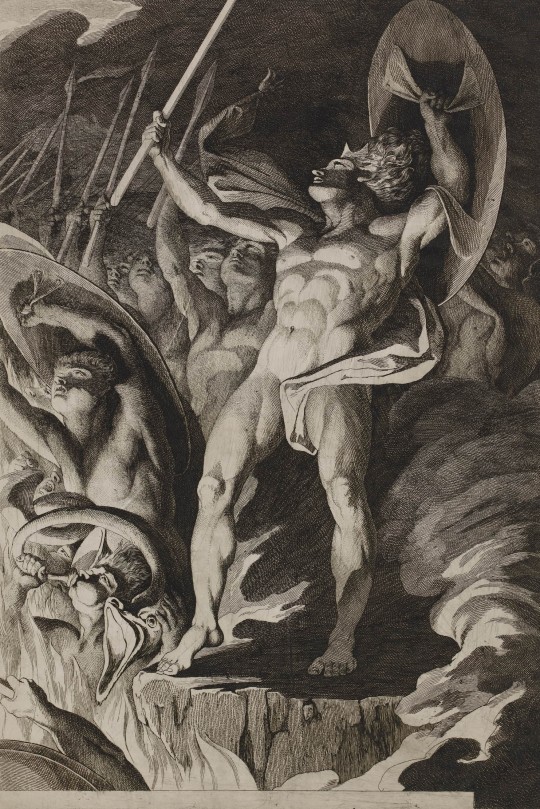

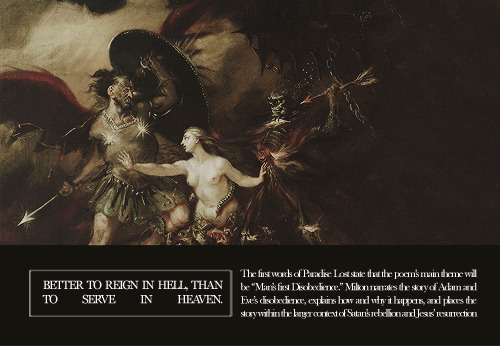

“Glanced on the ground, with labor I must earn My bread; what harm? Idleness ha been worse; My labor will sustain me.” -Eve, “Paradise Lost” book X, lines 1054-1056

Okay so I was building a response to Satan and his attractiveness based on something Professor Joubin mentioned in my Shakespeare class (that Milton was critiqued for Sexy Satan), but this quote right here sent me right back to Eden. I can’t get enough of Adam and Eve; they’re deeper and more interesting to me than Satan’s battle, perhaps because they’re so human.

This quote also strikes me because finals are upon me and I’m dying of stress. WHY does Eve think idleness is worse than labor? Granted, she’s never worked a day in her existence, so she’s not exactly speaking from a place of knowledge. To me, however, I think of the satisfaction that completing work gives me, coupled with Eve’s thirst for knowledge, and my heart breaks for her here. Eve is unhappy in Eden because she’s bored and unfulfilled. This quote not only reveals an inherent survival instinct not present in Adam but a determination to succeed. That’s the feeling I get when I pull my second all-nighter and I’m dancing the Macarena in the Gelman sixth floor bathroom--it’s absolute dedication to a cause no matter what.

Here, Eve is recounting how she felt BEFORE facing the reality of consequences, so there’s a sense of irritation and despair over her former foolhardiness. Such blatant lack of concern for her food source tells me that she has absolutely never worried about hunger, but now she must. The focus on bread specifically--in conjunction with labor--brings to mind images of Marx and how Eve as a working woman will be at the bottom of the new social hierarchy. She disobeyed God to grasp some power in Eden, but it failed, and now she’s even more subservient than before and all her previous wind is gone from her sails. I’d argue that deep, thoughtful characterization of Eve’s predicament is what makes “Paradise Lost” so dangerous; Milton shows that she’s wasting her potential and uninspired from the start, and it’s difficult to resist her logic. It’s difficult for me, at least--all I’d ever been told is that Eve ate the apple because she was stupid and weak. Milton’s complex Eve is more sympathy-inducing than this sexist, vapid cardboard cutout of Eve that’s survived to this day.

I feel that “Paradise Lost” has, overall, left me with a greater interest in how women appear in Biblically-inspired texts. These texts are important because the Bible provided--and continues to provide--framework for the legal, societal, and economic roles of Western women for millennia.

0 notes

Photo

Paradise Lost: Satan and His Legions hurling defiance toward the Vault of Heaven (1792/95 - Etching) - James Barry

[1st version on s4h]

852 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Knowledge forbidden?

Suspicious, reasonless. Why should their Lord

Envy them that? Can it be a sin to know?

Can it be death?”

literature posters; paradise lost by john milton

917 notes

·

View notes

Photo

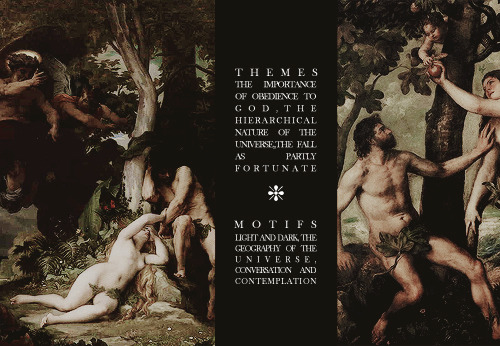

[ LITERATURE EDITORIAL SERIES ] John Milton’s Paradise Lost

↳ The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.

2K notes

·

View notes

Quote

O fairest of creation, last and best

Of all God's works, creature in whom excelled

Whatever can to sight or thought formed,

Holy, divine, good, amiable, or sweet!

Adam, Paradise Lost, Book 9, Line

For someone who sat in a middle seat on a plane for three hours with a misaligned spine rather than rouse my seatmate so I could walk in the aisle, I sure do love analyzing confrontations. This quote is the first thing Adam says to Eve after she confesses to biting the apple (and after he drops the handmade garland).

I have conflicting feelings over this moment, and I’ve chosen it because I think it’s a crucial scene in their relationship. On one hand, Goody Goody Adam’s first response to Eve’s betrayal of God is to sing her praises. He does so pretty lavishly, as he is wont to do when speaking of Eve, and views her over himself as the “last and best of all God’s works.” Adam’s two defining characteristics are that he loves Eve and he loves God, and it’s crucial that in this moment he still thinks of her as the “best of all God’s works.” Beyond love, I read a lot of terror in these words, too. The exclamation point at the end of the quote cements this feeling. He may not understand her, and he likely would have never touched the apple without her, but he still clearly loves her and the idea of losing her to the concept of death frightens him. I have to remind myself here that neither of them have ever seen anything die. He has NO IDEA of what will happen to her. In this situation, I’d be shrieking, so I believe it another indication of Adam’s love for Eve that he remains focused on her in this moment rather than panicking.

That being said, however, I did argue that “fair” meant beauty only in my last entry, and I still believe that in this context. Even when worrying over death, Adam is still focused on Eve’s beauty. He also highlights that she is “good” and “sweet,” two characteristics which showcase how little he knows of her relationship with both Eden and himself. I’ve read Eve as just going through the motions. I feel like Adam genuinely cares for Eve, but he just stares at her whenever she speaks without listening or really observing her. Eve claims earlier in the text that Satan would think it beneath his dignity to trick a “weaker” sex, but I wonder if it might’ve been even easier to fool Adam, given how hung up he is on Eve’s looks and little else about her. Okay, I know it’s weird to put myself in SATAN’S shoes, but I debated this for a bit and I think I’d prefer to trick Adam just because he’s so ditzy. I’d be too uncomfortable with the similarities between my story and Eve’s to go after her. Maybe that’s why I’m not Satan.

I like to think there are other reasons, too.

0 notes

Quote

So hand in hand they passed, the loveliest pair

That ever since in love's embraces met,

Adam the goodliest men of men since born

His sons, the fairest of her daughters Eve.

John Milton, “Paradise Lost,” Book IV, lines 321-324

I HATE Milton. I feel so bad saying that, too, because you clearly love his work so much. I hate saying that I hate texts that others clearly love--I can never be certain of how important the texts are to them. BUT I HATE MILTON. It’s all so dry to me. I wasn’t raised in a religious household, so a lot of the imagery and references are lost on me. I also think the poem is monotonous even if I recognize why it’s so respected. The aesthetics and syntax of it are remarkable.

The bashing concluded, however, I chose this section for my commonplace book because it carries a syntax riddle. Adam is the “goodliest men of men since born His sons” and Eve is “the fairest of her daughters.” Does this mean that God is both male and female? I’m excited to bring up this little issue during class on Tuesday; I think I wrote down “????” faster during this Commonplace Book Annotation Session (CBAS) than any other. I personally like the idea of God being both male and female, and all other genders, because the Creator then reflects the created. That being said, “her” is lowercase while “His” is capitalized. The poem’s structure does not outright reveal if this was intentional or not, given that “His” starts a fresh line. “His” is traditionally capitalized when speaking of God, and God is traditionally spoken of as male. Perhaps I’m misreading the entire section (which is likely), but I believe that the poem makes God at least two genders.

Eve, however, is noted as “fairest” while Adam is “goodliest.” This might just be semantics on my part, but “fairest” sounds more like Eve is the most beautiful daughter while Adam is good on multiple levels. There’s more room in “good;” I’d rather be good than fair. I feel that this is an allusion to their fates, and that Eve cannot be good because she ate the apple. It’s rather sexist to my modern ears to grant the male character a more complex trait while the woman is regulated to being pretty, but I recognize the struggle of characterizing Eve while also acknowledging her fate. Perhaps contemporary readers would object to a description of Eve that was too positive. I’m not strong on the seventeenth century, but I DO know that they were, of course, deeply religious. It’s difficult to know what would offend people if you didn’t live in their times. Either way, I wish Eve could be seen as something other than fair, if only because I’ve been reading this Twitter thread that lists how male screenwriters describe their female characters and times have not changed.

(Professor Dugan, you mentioned in class how Milton recited “Paradise Lost” to one of his daughters--I think it was Deborah Milton based off some Google searches. Did he have to specify specifically when each new line began, or did Deborah make some of those calls? I’m going to ask at the beginning of Tuesday’s class. This aside is just to remind me to ask.)

0 notes

Quote

With that the Empress thanked the Duchess and, embracing her soul, told her she would take her counsel.

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World, page 183

Once again, my illness prevented me from reading this in a timely manner with the rest of the class. I am now back on track and look forward to diving into Milton tomorrow! Stay tuned.

BUT FIRST I NEED TO EXPRESS MY FEELINGS ON THIS HOMOEROTICISM. I know this is a line we very briefly touched on in class, but I was excited to read this particular part, and its entirety did not disappoint. What strikes me here is the tender language Cavendish uses to express the Empress thanking her fictional self. To “embrace her soul” is such a romantic expression! The Empress is focusing on Cavendish’s mind over her looks, and clearly values her help. That being said, it is unclear what the Empress is doing here. She cannot physically embrace a soul, so are the two women just hugging? Or doing something else? This line would cause me to slam my head against a table were I writing a screenplay based off Cavendish’s work. This goodbye is crucial in the relationship of the two women, and yet it’s told in veiled language. I think it’s Cavendish’s way of avoiding openly expressing feelings that are not socially accepted.

A similar quote is given on page 202, where the “Empress’s soul embraced and kissed the Duchess’s soul with an immaterial kiss, and shed immaterial tears, that she was forced to part from her.” If Cavendish did essentially write herself a girlfriend, she’s placed said girlfriend higher above her in the social system, and thus the Empress is the one instigating the kissing and the embracing. It speaks volumes as to how entrenched Cavendish is in the aristocracy (the work also defends the system that made her and her husband both rich and titled) even in her fantasy world. I’m debating delving into homoeroticism in Cavendish’s work as a longterm project but I am, ironically, already researching Virginia Woolf. I feel that I need to separate my research of these ladies’ lives!

1 note

·

View note

Quote

The windows likewise were not crowded, but every one stood in them as if they had been placed.

Francis Bacon, New Atlantis

First of all, forgive the late entry. I felt under the weather most of last week and that escalated into full-blown illness this weekend, so I never had the energy to type out an entry until now.

THIS. SENTENCE. IS SO. EERIE. I’m fascinated by the language used here. The narrator doesn’t just say that everyone looked orderly--no, someone looked to have placed them where they stood. It reminds me of doll houses, stage plays, and North Korea (not necessarily in that order). I pointed out in class discussion that the idea of citizens being placed goes hand-in-hand with Bensalem’s intense religious devotion. Perhaps they were placed by God? But even then, it’s still spine-chilling. Bacon couldn’t have imagined the context in which future readers would read his words. He didn’t have anything close to North Korea in the highly globalized world in which we now live. (Because you were absent, Professor Dugan, you missed a lively discussion about how Bensalem might have snipers mounted to take the Spanish sailors out. It seems that this sentence triggered a specific line of class discussion in which Bensalem transformed into an armed-to-the-teeth, CIA-style island. Perhaps modern Bensalem has received an upgrade?)

The sentence also drew my attention due to the sudden note of fear I read in it. We don’t actually know what happens to this (fictional) protagonist. He says only good things about Bensalem until this particular line, wherein there’s slight doubt over the perfection. The work is left “unperfected” mere pages later. I worry that the narrator does not survive his journey into Bensalem, and that the discomfort I feel at this line is proof of his (fictional) death. It makes no sense to me that Bensalem should struggle for hundreds of years to keep their island a secret, plan everything out to perfection, and then just hand it over to a couple of wandering pirates. (I do, by the way, believe the pirates are Christians, but really bad Christians at that.) The governor has no way of proving anything about these wanderers, and the controlling nature revealed in the quote makes it unlikely that he would ever be so free with priceless information. I think the sailors ultimately die on Bensalem. But then who, in this fictional universe, delivers the manuscript to the outside world??? I just can’t figure this out!

0 notes

Photo

Page decorations by T. H. Robinson for Una and the Red Cross Knight, and Other Tales from Spenser’s Faery Queene, 1905.

5K notes

·

View notes

Quote

Thy gowns, thy shoes, thy beds of roses,

Thy cap, thy kirtle, and thy posies

Soon break, soon wither, soon forgotten--

In folly ripe, in reason rotten.

Walter Raleigh

GO. OFF. WOODLAND. NYMPH. I think this is my favorite text of all we’ve read, and my love is 50% form and 50% meaning. I chose (with some difficulty) this passage because I love its deliberation. In listing the earthly pleasures which cannot last, the nymph is--to me--being quite cruel. I read this poem thinking that she could have let him down easy, and then it hit me that women are CONSTANTLY told to be nicer to men. She doesn’t have to be nice! She can firmly express that a relationship with the shepherd is not beneficial to her. I imagine that she’s got a pretty good life going for her already and she doesn’t want to throw it away over some guy. While the materialistic aspect highlighted in my chosen quote might seem tacky at best and horrifically cruel at worst, I personally believe that it showcases a woman’s unstable position in romantic negotiations. I’m unsure if woodland nymphs were able to own property and easily divorce in Elizabethan society (indeed I am woefully ill-informed on woodland nymph rights in 2018), but human women essentially belonged first to their fathers and later to their husbands. If the nymph gives herself over to what I imagine is the 35th shepherd bellowing into her woods that month, she could lose her independence and would have to live as a restricted woman in society. As for the form of this passage, I feel that listing off the items offered (and rejected) shows that the nymph has carefully considered each one and consequently says No. She doesn’t brush off this suitor; she takes the time to compose this poem and to list his offers. I think, however, that she doubts the authenticity of the shepherd’s love. She focuses on the property breaking down rather than their relationship, and views this as an inevitability that their love will not overcome. The usage of “folly” and “reason rotten” suggest that she has no doubt in her mind that disaster will strike, and the repetition of “soon” further reinforces this looming doom. The nameless nymph has said No, and the shepherd--along with the reader--should respect that.

1 note

·

View note

Quote

And weeping said, Ah my long lacked Lord,

Where have ye bene thus long out of my sight?

Much feared I to have bene quite abhord,

Or ought have done,° that ye displeasen might,

That should as death° unto my deare heart light:

For since mine eye your joyous sight did mis,

My chearefull day is turnd to chearelesse night,

And eke my night of death the shadow is;

But welcome now my light, and shining lampe of blis.

Edmund Spenser

I AM SO ANGRY. UGH, my girl Una deserves so much more than this sorry excuse for a knight. My heart actually jumped when I read that she was weeping over this loser abandoning her. He has a job to do and he proclaims to be honoring his dead Lord in doing it, so WHY is he just let off the hook for abandoning the woman he’s supposed to be accompanying? This forest is crawling with all sorts of nightmares and he just DITCHED HER. Redcross must have known that she could’ve died without a companion. Does the idea of her losing her “purity” really amount to her death??? REALLY, REDCROSS. REALLY, SON. I personally think her physical danger is reflected in the physical language Spenser incorporates; Una speaks of Redcross leaving her sight rather than deal with abstracts of the heart. She admits that her “chearefull day is turnd to chearelesse night” and that she’d rather die than fall out of favor with him, but I refuse to believe that some of this wailing is not the result of her being lost, tired, and scared in the forest. I’m reading Much Ado About Nothing in Professor Joubin’s class, and I see connections between Redcross and Una and Claudius and Hero, mainly that the women deserve the world and the men need to get over themselves. This stanza stuck out to me precisely because I wished Spenser had included a mini Una rant. If she’s meant to be Truth, she should tell Redcross that he ditched her based on shaky logic and that he must not love her if he can leave her so soon. I want an entire canto of Redcross trailing after Una, the lamb, and the Dwarf apologizing to her indifferent profile. I want the lamb to spit on him, but that’s mostly just me wanting a symbol of “purity” fighting back. Anyway, Redcross is trash and the Una Support Group will meet on Fridays at 5pm in Funger 423.

0 notes