Photo

ALIGNING GRAFFITI PRACTICE WITH THE CITY OF SYDNEY’S ‘CREATIVE CITY PLAN (2014-2024)’ | Cultural Policy Discussion

This essay argues for the City of Sydney to adopt an open policy toward street art and graffiti. Current policies based on the Graffiti Control Act (2008) fail to engage critically with graffiti practice, expose a desire for control, and miss out on opportunities to align graffiti with broader cultural aims. The research draws on theories about place-making, the creative economy, property relations, and cultural democracy to ponder how graffiti might be incorporated into the Creative City Cultural Plan (2014-2024). In particular, as a networked practice that adapts well to new media, graffiti has the power to reactivate non-places, reveal gaps in policymaking, and add to conversations about creativity in the city. Moving past an arbitrary distinction between street art and graffiti, one celebrated, one scorned, the City should recognise these forms as part of a networked subculture. Repressing graffiti would drive activities underground and create more risks for artists whereas nurturing creative hubs around this practice might help them become drivers of urban growth. Allowing graffiti to evolve over time would pave the way toward cultural democracy and enhance citizen input in policymaking. A mindset for co-existence, then, fosters innovation and connectivity, the basis for a thriving Creative City.

Read now

#cultural policy#graffiti#street art#policy discussion#cultural democracy#creative economy#posts text#sydney#graffiti vs street art

0 notes

Photo

How Youtube Reshapes Political Communication in the US | Media & Politics Essay

Research Question: Rather than a tool for reclaiming democracy, might Youtube be disruptive to political communication and civic engagement in the US?

In the 2020s, Youtube has become a key site for political communication. The platform’s prowess lies in its assembly function as a part of citizens’ everyday news consumption (Ricke, 2014). The emphasis on user generated content and absence of official commentators/ mediators prompts us to marvel at Youtube’s potential to bolster democracy. However, due to the potency of its commercial interests and algorithmic control, Youtube might actively promote certain content at the expense of others, locking users in echo chambers, creating political fragmentation and incivility. Rather than tackling unequal access, this social media site enables established actors to project a stronger voice, drowning out counter viewpoints, at the same time appealing to the politically-motivated while neglecting marginalised demographics. Worse still, tech companies collaborate with media and government agencies in exacerbating political selectivity and contrived rhetorics (Messing & Westwood, 2012) (Cho et al., 2020). Through a case study of Obama’s campaign strategies and the proliferation of online sources during COVID-19, this essay argues that as a hidden shaper of public discourse, Youtube fails to fulfill the democratising promise of Internet technologies.

Read now

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Tracing The Feminine Consciousness Within The Record Hoàng (2019)

Research Question: How does the pop album Hoàng (2019) by Hoàng Thuỳ Linh employ folk materials to imbue the reductive framing of Vietnamese femininity with subjectivity?

Abstract: This paper studies the messages about Vietnamese womanhood that can be inferred from the 2019 folk pop record Hoàng by Hoàng Thuỳ Linh. The research draws on the feminist consciousness in Vietnamese folkloric and historical materials to establish a link between literary expressions and national imaginings of femininity. While neither a writer nor poet, Hoàng Thuỳ Linh is an artist whose products hold textual significance with younger audiences. To reclaim the space of Vietnamese femininity, it is fitting that Hoàng Thuỳ Linh's third album – often criticised for its trivial subject matter – refrains from the constricting language of nationalism, focusing instead on sentiments and personal laments. Her rise back to power as a woman harmed by the industry/ patriarchy showcases how pop music might continue the legacy of folk genres in contesting the ideals perpetuated by a patriarchal state. Hoàng (2019) thus signals the emergence of a hybrid genre capable of accommodating new existences and engaging new audience groups in the continued fight for diverse femininities

Context: In 2007, the then 19-year-old actress Hoàng Thuỳ Linh, beloved for her role in the teen sitcom Vàng Anh's Diary (2006), fell victim to the biggest sex scandal in Vietnam’s entertainment history. Her starring role was cancelled while the public exploited intimate images of her to preach female virtues and propriety. A decade later, with her third studio album Hoàng (2019), Hoàng Thuỳ Linh has reinstated herself as a trailblazing artist. Blending folk elements with electro-pop, Hoàng instantly became acclaimed for its hybrid form upon release on Vietnamese Women’s Day (October 20th).

Word count: 3,500

View

#thesis#research paper#Hoang (2019)#Hoang Thuy Linh#v-pop#feminist media#vietnamese literature#vietnamese feminism#posts text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Table of contents

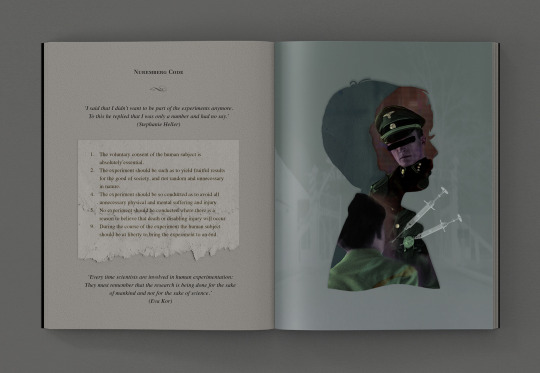

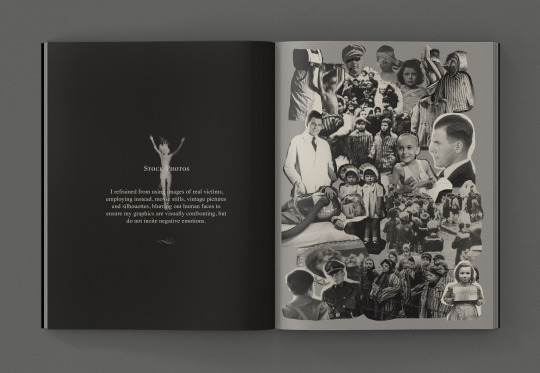

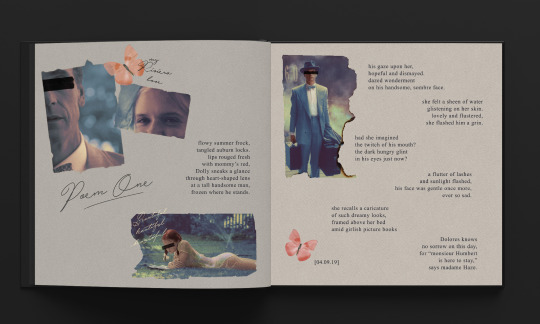

Poems for Lolita | Creative Writing x

The Mengele Twins Booklet | Creative Response x

Reputation Redrawing: Process Explanation | Taylor Swift-inspired Creative Project Part I x

Re-Storying Wildest Dreams: Process Explanation | Taylor Swift-inspired Creative Project Part II x

A Fashion Practice Underlined By Storytelling | Feature Writing x

‘Go-Go Sisters’ (2018) - A Cinema of Girlhood | Screen Analysis x

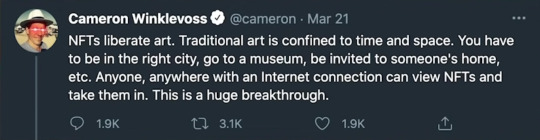

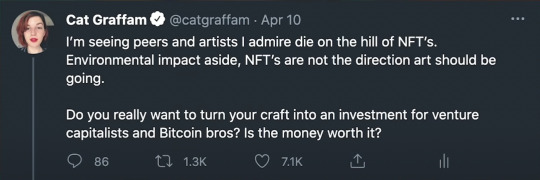

When “Finance Bros” Infiltrate the Art Scene | Argumentative Essay x

How Youtube Reshapes Political Communication in the US | Media & Politics Research Essay x

Aligning Graffiti Practice with the City of Sydney's ‘Creative City Plan (2014-2024)’ | Cultural Policy Discussion x

K-Horror and J-Horror: Contending with National Anxieties | Critical Media Analysis x

A literary review of Vietnamese women’s struggle for self-determination | Gender Studies x

Tracing The Feminine Consciousness Within The Record Hoàng (2019) | Postgraduate Dissertation x

PR work samples (Social Media Campaigns, Event proposals, etc.)

0 notes

Photo

Creative Project | Media Manipulation Part. 2

When one’s love for Taylor Swift translates to an extended creative project. Combining graphic design, theories in digital literacies, and Swiftie-ism in a two-part blog series that yielded a High Distinction and became an exemplar for future students undertaking the FDL001 course at UTS College.

For the second and final part of this extended media project, I have chosen to make a GIF set out of my favorite song/ music video by Taylor Swift, "Wildest Dreams", released in August, 2015, the 5th single for her 5th studio album “1989″.

Preview

Benjamin finds that “mechanical reproduction is a technique of diminution" that helps people achieve control over works of art by possessing copies of the original. [...] Perhaps, instead of a diminishing effect, reproduction helps to liberate and extend the aura of artworks by making them readily available and accessible to all social classes.

As such, I intended for this GIF set to extend and renovate the aura of the original "Wildest Dreams" music video, which is set in an African savanna in the 1950s during the golden age of cinema.

Their love is like a spectacle, picturesque and too good to be real, it is witnessed by the director and camera crew like a movie being watched by an audience. All the equipments were telltale signs that permeated the privacy and substance of a tangible connection.Yet, all these signals jabbing at the ephemeral nature of Finn and Kingsley’s love story have been selectively omitted from my GIF set after a careful process of sourcing footages.

Relationships can be superficial but memories have enough merit and power to outweigh the negatives. Perhaps what Swift is trying to say to her lover, is “you’ll see me again, in a warm memory”; and this GIF set serves to encapsulate that warmth.

Reconfiguring “aura” in the era of digital (re)production

The main inspiration for this creation is once again, the concept of "aura" developed by Walter Benjamin (1970) in The Work of Art in The Age of Mechanical Reproduction. For Benjamin, aura is 'the here and now' of a work of art. Historically, tangible artworks made for traditional mediums possess an appearance of supernatural force as well as sensory experience of distance, both of which arise from their unique presence in time and space.

"What withers in the age of the technological reproducibility of the work of art is the aura." (Benjamin 1970)

Benjamin finds that “mechanical reproduction is a technique of diminution" that helps people achieve control over works of art by possessing copies of the original. On the one hand, aura, authenticity, and uniqueness of original artworks are fundamentally connected to their insertion in traditions. Therefore, reproduced works of art are completely detached from the sphere of tradition. Envision for example, how the aura and unapproachability of a leather-bound, original work of classic literature is reduced when cheap paperback copies of it are sold unceremoniously on sidewalks.

On a positive note, this waning of aura and thus, loss of tradition, means the work of art can be disconnected from its past uses and brought into new combinations by the reader through various resources such as language, gaze, gesture, vocal features, proxemics, graphic display, cinematography, page-layout, etc. Perhaps, instead of a diminishing effect, reproduction helps to liberate and extend the aura of artworks by making them readily available and accessible to all social classes. Digital art is especially susceptible to this phenomenon as it can be transmitted very quickly through various media outlets whilst preserving the essence of the work. Although digital media lack the gravitating effect and semblance of distance traditional artworks possess, they are multimodal products which can transmit a diverse range of emotions through camera lens, digital mediums and networks, invoking an entirely new and distinctive sense of atmosphere/ quality.

As such, I intended for this GIF set to extend and renovate the aura of the original "Wildest Dreams" music video, which is set in an African savanna in the 1950s during the golden age of cinema. It tells the story of fictional brunette actress Marjorie Finn (played by Taylor Swift in a wig) while she shoots a romantic adventure film with co-star Robert Kingsley (played by Scott Eastwood). Finn and Kingsley are having a love affair both on and offscreen, but their romance is short-lived and bittersweet as the video cuts to the movie premiere, where Finn sees her co-star Kingsley with his fiancé. Finn is visibly upset but tries to act nonchalant. As they both watch the film, Finn is finally overcome with emotion, fleeing the premiere and getting into a waiting limousine. The video ends with a shot of the limousine's side-mirror showing Kingsley running into the street and watching as Finn's car drives away.

(Watch the Full Music Video on Youtube for a more immersive experience)

Multimodality Analysis & Creative Process

The song and MV's title “Wildest dreams” invokes elements of romance and fantasy, it is the opposite of reality which suggests harsh truths and coming to terms with something negative; It is also a connotation of something lovely but unattainable (not just a dream but the “wildest” of those dreams). In the original video, the love story between Finn and Kingsley mainly unfolded on a movie set, which is a clear metaphor for something inherently false and temporary. Anytime the audience witness these lovers kiss, our views are obstructed by cameras and filming equipments. The lyrics also suggest a public disclosure of private thoughts, since Swift is directly addressing a “you” in the chorus (“Say you’ll remember me…”), it’s as if she wrote the song with the assumption that her lover is going to hear it in mind. Their love is like a spectacle, picturesque and too good to be real, it is witnessed by the director and camera crew like a movie being watched by an audience. All the equipments were telltale signs that permeated the privacy and substance of a tangible connection.

Yet, all these signals jabbing at the ephemeral nature of Finn and Kingsley’s love story have been selectively omitted from my GIF set after a careful process of sourcing footages. In doing so, I hope to evoke a different “aura” from the work and highlight what I deem to be the true message Swift is conveying through her song - lustful, bad decisions and doomed relationships are all worth it, as long as they are remembered fondly, through rose-tinted glasses and warm memories that remain.

Right before the chorus starts, Swift sings “I can see the end, as it begins” - meaning she already knew they were star-crossed lovers, doomed from the beginning to have a lovely but fleeting relationship. Yet, this lyrics is immediately followed with “My one condition is…” (not “I wish we never met” or “I wish I never kissed you”) which brings focus to the fact that she doesn’t regret having fallen for or been together with “him”. She can accept the ending of their love, as long as she is remembered by her lover “in a nice dress” while “staring at the sunset”, a key imagery in the music video. Although this sequence contains amazing visuals, the beautiful synchronization between the massive, flowy gown and the wind is actually facilitated by a fan. Yet, when I captured it in the 3rd GIF, I eliminated any element that would suggest artificiality, because as long as the image of Finn in this fashion is remembered fondly by Kingsley, their star-crossed love would be romanticized in memory and retain its value.

Artificial wind making Finn's dress blow in the wind.

I captured their short-lived but intense romance in a series of curated footages: from the moment Finn and Kingsley first laid eyes on one another and recognized the spark of attraction, to the times they’ve spent in each other’s company in private chambers and amid the African sky, to the period their movie enters post-production stage and the two are separated by reality, forced to witness their doomed relationship on film like picture perfect memories.

I color corrected the GIF set so that tones of cyan, yellow, green and any other shades signifying the reality of the African geography their movie set is based on would disappear, bringing sole focus to the rose-colored love portion of this story. In addition to limiting the range of color to strip away elements of reality and encapsulate the story in visually altered memories, I also slowed the pace of action down for certain scenes to stretch out the moment and evoke emotional affects:

when Finn and Kingsley make eye contact (GIF 1)

when Finn’s dress blows in the wind against the sunset backdrop (GIF 3)

when Finn is mouthing “Wildest dreams” right before leaning in for an on-screen kiss (GIF 7)

when Finn runs away from the theatre in anguish (GIF 9)

The lyrics “nothing lasts forever” is repeated several times throughout the song, but contextualized in different manners, ringing out when Finn and Kingsley are shown smitten and in love, but also in the midst of the relationship’s doom. I wanted to emphasize another lyrical notion: “Say you’ll see me again/ Even if it’s just pretend” which comes right before the climax of the song and is delivered by Swift in a confessional tone without loud musical backtrack to distract from its raw, emotional quality. I incorporated the heartbreaking plea in text on top of GIF 3 (which conveys the lyrics “say you’ll remember me/ standing in a nice dress/ staring at the sunset”) and GIF 6 (when Finn and Kingsley are shown happily enjoying each other’s company and gazing at one another with intense emotions).

The result is a series of tinted, romanticized GIFs that strips away all elements of artificiality to emphasize the authenticity of an albeit short-lived romance. The visuals fool the audience just as Swift intended the memories to fool her lover. Relationships can be superficial but memories have enough merit and power to outweigh the negatives. Perhaps what Swift is trying to say to her lover, is “you’ll see me again, in a warm memory”; and this GIF set serves to encapsulate that warmth.

A note on accessibility

The GIF set is to be viewed from Top to Bottom and from Left to Right. I have written captions that double as alt texts describing the storyline(s) behind each individual GIF.

[Gif 1] Scene 1: Finn & Kingsley making eye contact/ Scene 2: Finn & Kingsley kissing.

[Gif 2] Camera pans into a tent bedroom setting, Finn & Kingsley are seen sharing a bed as lovers.

[Gif 3] Finn's long dress flowing in the wind/ camera transitions to a helicopter flying towards the sunset/ Text reads: "Say you'll see me again".

[Gif 4] Scene 1: Kingsley holding Finn's face/ Scene 2: Finn watching wild elephants amid the African desert setting/ Scene 3: Kingsley holding Finn from behind as they both serenely gaze at the sunset.

[Gif 5] Scene 1: A frowning Finn slowly smiles as Kingsley gently tilts her face towards him for a kiss/ Scene 2: Finn reaching for Kingsley's hand as he operates the helicopter/ Scene 3: Finn & Kingsley's helicopter flying amid the sky.

[Gif 6] Scene 1: Kingsley lifting Finn and spinning her in the air, both are joyfully laughing/ Scene 2: Kingsley gazing at Finn intensely and sadly/ Text reads "Even if it's just pretend".

[Gif 7] Scene 1: A distraught Finn turns away from Kingsley at the premiere of their movie/ Scene 2: Black and white screening of Finn & Kingsley's movie interaction, Finn mouthing "Wildest dreams".

[Gif 8] A heartbroken Finn fleeing the theatre and slamming the limousine door shut, gazing through the glass longingly.

Since one of the most important aspects of digital literacy is accessibility for all people, my decision to add alt texts and alter the titles of each GIF according to their content serves to ensure those with visual impairments can also "view" the media. Ideally, alt texts should be informative and concise (about 125 characters or less to ensure compatibility for popular screen readers), relating only the central aspects within images. Here, I have incorporated more detailed descriptions since the media being wielded are compilations of moving images made up of several scenes and storylines. I refined these alt texts by closing my eyes and considering whether the elements I had described help to paint a clear picture of the "Wildest Dreams" MV in my head, without the aid of vision.

Reference List:

Benjamin, W. 1999, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical reproduction’, in H. Zohn [ed], Illuminations, London: Pimlico, pp. 211-244.

Finefrock, M. 2015, Making Web Images Accessible to People Who Are Blind, Conscious Style Guide, viewed April 27th 2018, <https://consciousstyleguide.com/making-web-images-accessible-people-blind/>.

Panzironi, M. 2016, Animated GIFs And Fair Use: What Is And Isn't Legal, According To Copyright Law, Forbes, viewed May 19th 2018, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/propointgraphics/2016/04/30/animated-gifs-and-fair-use-what-is-and-isnt-legal-according-to-copyright-law/#6d193844371b>.

Robins, A. 2011, Theory in Studio: Walter Benjamin and the Concept of Aura, Burnaway: The Voice of Art in the South, viewed April 25th 2018, <https://burnaway.org/feature/theory-in-studio-walter-benjamin-and-the-concept-of-aura/>.

Robinson, A. 2013, Walter Benjamin: Art, Aura and Authenticity, Ceasefire Magazine UK, viewed April 25th 2018, <https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/walter-benjamin-art-aura-authenticity/>.

Valkenburgh, P. V. 2014, Do Animated Gifs Infringe on Copyrights?, PeterVV, Personal Website, viewed May 19th 2018, <http://www.petervv.com/2014/01/04/do-animated-gifs-infringe-on-copyrights/>.

VERONIIIICA 2018, How to Write Alt Text and Image Descriptions for the visually impaired, Perkins E-Learning, viewed April 27th 2018, <http://www.perkinselearning.org/technology/blog/how-write-alt-text-and-image-descriptions-visually-impaired>.

Copyright Disclaimer

The Copyright Act allows certain unauthorized uses of copyrighted materials by creating a number of exceptions to those exclusive rights (Valkenburgh 2014). The most relevant exception for GIF making is called "Fair Use” - when the original material is used for a limited and 'transformative' purpose, such as education, commentary, criticism or parody. A GIF might be viewed as transformative because it’s not a long film or TV show telling some story; it’s a very short moving-image on the internet that expresses a simple idea. For this blog post, I would categorize the use of footages from the “Wildest Dreams” music video as fair and for a transformative purpose (critical commentary and education) on a private blog post. I acknowledge that the footages fully belong to Big Machine Records; I do not intend to publish these GIFs on any other site for marketing, competition, personal profits or exposure.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

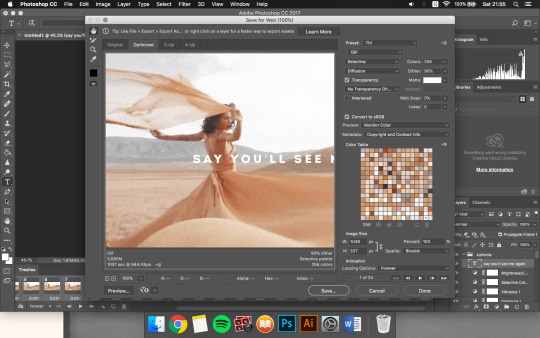

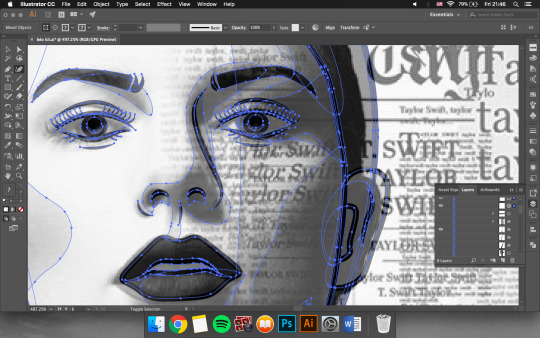

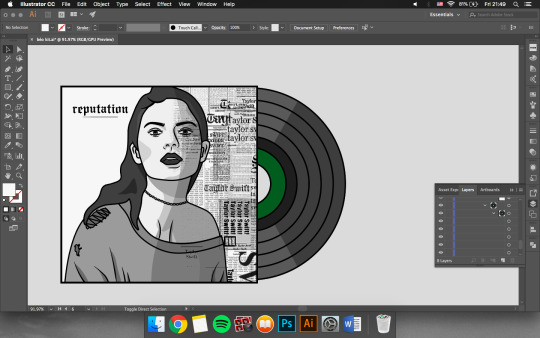

Creative Project - Media Manipulation Part. I

When one’s love for Taylor Swift translates to an extended creative project. Combining graphic design, theories in digital literacies, and Swiftie-ism in a two-part blog series that became an exemplar for future students undertaking the FDL001 course at UTS College.

Chosen Media: The official cover art for Taylor Swift's 6th studio album Reputation.

Digital Manipulation: A redrawing of the original cover art using Adobe Illustrator.

Duration: 6 hours (drawing + reflection).

Vectorized re-drawing of the Reputation album cover art.

One of my inspirations for this creation is the concept of “aura” developed by Walter Benjamin (1970) in The Work of Art in The Age of Mechanical Reproduction. For Benjamin, there exist three types of reproduction: first, that of the “pupil in practice of their craft”, second, that of the “master for diffusing their works”, and finally, that “by third parties in the pursuit of gain”. Considering the technological advances and cultural shifts that have reshaped the modern mediascape, scholars have elected to add a fourth category to Benjamin’s spectrum of reproduction, that of reproduction in a digital landscape (Robins 2011). This term refers to the reproduction by an individual, not in pursuit of wealth but for personal association. It is the reproduction that exists on an individual’s website or blog, stored on their hard drive or pinned to their wall, the adoption of an artwork as a token of taste, an indicator of their curated persona.

Inspired by this so-called "fourth category" of mechanical reproduction, I have decided to employ my literacy in using Adobe Illustrator to recreate the latest album cover art by my favourite artist, Taylor Swift. Although the original artwork was consulted and referenced extensively, I did a complete re-drawing of it using primarily the Curvature Tool within AI. Based on my research on copyright infringement and licensing, I have concluded that my work cannot be distributed to the public for neither profits nor exposure. This policy coincides with my initial decision to keep the final digitally manipulated cover art for my own personal use as a wallpaper. I do not intend to publish it anywhere else nor sell prints of it under any form as part of my aspirations to adhere to the ethical principles of producing and consuming digital media.

Due to my attachment to the original album cover, the re-drawn artwork retains almost every detail in a nearly identical manner, albeit simplified for the vectorized format. In order to justify my artistic decision to recreate this particular image, I have conducted a brief analysis of the multimodal elements employed in the Reputation cover art as well as the meanings they work together to convey.

In the cover art, Swift's face is featured alongside headlines and newspaper prints. But when viewers zoom in, these texts simply state "Taylor Swift" repeatedly. Without even using any real words, spectators can surmise that this is a reference to the endless headlines and stories the singer has spurred in recent years. Whether that alludes to her feud with Katy Perry or whirlwind romance with Tom Hiddleston. Depending on various possibilities for interpretation, Taylor could either be embracing the spotlight, reclaiming it, or even mocking the excessive attention. Either way, the album art makes it clear this is her moment to set the story straight. She's taking her reputation into her own hands and altering what the public think when they read the name, "Taylor Swift."

The Reputation cover art is noticeably toned down in colour, the palette ranges between shades of light and dark grey. I interpret this colour scheme, or lack thereof, as the manner in which Taylor Swift is portrayed by the media: harsh, merciless, the contrast between black and white represents two polars of extremity. Additionally, only half of her face is buried under layers of text, meaning that the newspapers only cover one side of Taylor’s multifaceted life. Despite the fact that her career spans a whole decade, this is the first time Taylor has released a monochromatic album cover art, signifying the first time she showcases her dark side to the public. Considering the bad rep she has consistently accumulated in recent years, most notably the notion that she is a sly, scheming “snake” posing as America’s sweetheart, this artistic choice is like a clapback against all the rumours, criticism and opposers. Taylor has wielded this so-called “reputation” to her advantage and embraced her media image as a ruthless woman. Taylor is poised at the centre of the cover, the camera cuts a closeup portrait of her upper body and her face is the most visually-popping element, demanding the attention of spectators. My favourite aspect about the artwork is her gaze: directed at whoever’s viewing the cover, simultaneously defiant and nonchalant; it conveys more than anything the ease with which Taylor is dealing with all the distorting news. Finally, the title of her 6th studio album and official comeback to the music scene “Reputation” is written in black, bold, cursive text at the top left corner of the cover, in the “New York Times” font, a reference to the famous newspaper.

Digital manipulation progress:

Since I have a background in graphic design, I didn't struggle much in figuring out how to achieve the desired digital effect. Perhaps, the most challenging aspect is staying committed to the process for several hours without getting too absorbed in the work and losing my grasp on real-life proceedings. Since I have been working with graphic softwares for a long time now, I tend to enter an isolated state of mind where my artistic/ digital literacy instincts take over so that the work I do is almost mechanical. Because of this instinctive fluency, although I have spent many hours on the redrawing, I find it difficult to document my thought process behind its creation.

Zoomed in progress #1: tracing minor details (eg: individual eyelashes)

The finished vector artwork without the original cover art overlay

Final outcome of the record peaking out from the vectorized cover art

The most prominent detachment from the original cover art is perhaps, the vinyl record with a green-labelled centre. I incorporated this element to satisfy my personal preference to feature an additional colour aside from black, white or grey in the final drawing. I chose dark green as a nod to Taylor's media persona (i.e. Snake); the record also serves to further differentiate my work from the original photograph.

References

Benjamin, W. 1999, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical reproduction’, in H. Zohn [ed], Illuminations, London: Pimlico, pp. 211-244.

Finefrock, M. 2015, Making Web Images Accessible to People Who Are Blind, Conscious Style Guide, viewed April 27th 2018, <https://consciousstyleguide.com/making-web-images-accessible-people-blind/>.

Robins, A. 2011, Theory in Studio: Walter Benjamin and the Concept of Aura, Burnaway: The Voice of Art in the South, viewed April 25th 2018, <https://burnaway.org/feature/theory-in-studio-walter-benjamin-and-the-concept-of-aura/>.

Robinson, A. 2013, Walter Benjamin: Art, Aura and Authenticity, Ceasefire Magazine UK, viewed April 25th 2018, <https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/walter-benjamin-art-aura-authenticity/>.

#reputation#blog post#multimodal media#creative response#graphic design#reflective writing#process explanation

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Gender Studies Essay | Literary Analysis

Female virtue, subservience and patriotism: A literary review of Vietnamese women’s struggle for self-determination. (2018)

➢ How cultural norms construct gender identity: A study into Vietnam’s history and literature to trace Confucianist ideas of female morality and sexuality which inform the socialization of past and modern Vietnamese women.

➢ An examination of literature as an advocacy tool for subverting sociocultural norms & promoting women’s rights.

Socialization and moral inscription upon the bodies of Vietnamese girls

“By contrast, since a girl’s biological making dictates that she cannot continue her father’s lineage, her body is assumed to possess neither the historical depth nor inborn morality associated with a penis.”

To acknowledge the performative nature of gender (Butler 1990), one must recognize the sociocultural dimension embedded in its history that subjects gender to regulation by social scripts and cultural norms (Cameron 2006, p. 421; Bartky 2000, p. 330). Since the most pervasive of these governing principles emphasize ‘the discipline of normative femininity’ and establish a disparate power dynamic that inscribes male bodies with a ‘mechanism of dominance over female’, (Taylor 2013, p. 404), ‘inegalitarian and asymmetrical treatments of the female body’ are inevitably constructed to ‘disempower women in a male-dominated culture’ (Bartky 2000, p. 326).

In Vietnam, a culture that adheres to the Confucian tradition of patrilineal ancestor worship, individuals are bound by moral obligation from the day they are born to ‘produce a [male] progeny and continue one’s bloodline’ (Rydstrom 2002, p. 359). A child’s body thus becomes a ‘socio-symbolic sign that reflects local life in terms of hierarchies’ (Rydstrom 2002, p. 359). The phallus is imbued with symbolic meaning so that boy’s bodies are perceived as a vital link between ‘the deceased and the living members of a lineage’; their capacity to maintain the bloodline is aligned with ‘inborn morality, honor and reputation’ (Rydstrom 2002, p. 361). By contrast, since a girl’s biological making dictates that she cannot continue her father’s lineage, her body is assumed to possess neither the historical depth nor inborn morality associated with a penis. Even though every child must undergo ‘socialization’, a notion encapsulated by the popular saying “các cháu như một tờ giấy trắng" likening children to blank canvases, ‘girls are perceived to be more blank than boys’, and in special need of social inscription (Rydstrom 2002, p. 363).

“The Other” and the role of literature in enforcing feminine norms

“Through a complex and often unconscious process of cultural osmosis, many Vietnamese women have adopted exemplary feminine traits embodied by the ideal woman that emerged from ‘a sea of literary characters in Viet proverbs, fables, books, plays and songs’ (Huynh 2004, p.6).”

The situation of woman is that she is victimized and ‘alienated from her own body’ by a phallocentric culture (Young 1992, cited in Bartky 2000, p. 323); compelled by patriarchal beliefs to ‘assume the status of an inferior Other’ (Bartky 2000, p. 321). The lack of a male body permanently informs a female's position as an outsider within the household: while ‘men represent the ‘inside lineage’ [họ nội]’, women are said to ‘belong to the ‘outside lineage’ [họ ngoại]’ (Luong 1989, cited in Rydstrom 2002, p. 362). A daughter would eventually be married off and settle into another household, the patrilineage ends upon the mixing of her bloodline with that of her husband’s; meanwhile, sons can remain to fulfill filial piety and carry out ritual obligations for his parents’ funerals and ancestors’ annual death celebrations (Chanh 1993; Luong 1993; Malarney 1996, cited in Rydstrom 2001, p. 362).

Being a female, or the Other, entails a continuous ‘demonstration of good female morality through the practice of sentiments’ [tình cảm] - a social capacity manifested in gentle, demure actions and words to ‘verify that one lives in harmony with others’ (Rydstrom 2001, p.398); only in doing so can girls accumulate honor and good reputation for their father’s lineage and ‘compensate socially for their bodily defined outside position’ (Rydstrom 2002, p. 373).

In defining a woman as “Other”, men have stolen from her ‘the opportunity for self-definition’, without which, she is led to seek social acceptance by ‘internalizing patriarchal norms of femininity through myths and stereotypes’. (Barky 2000, p. 324). For Vietnam, known to be ‘one of the most intensely literary civilizations on the face of the planet’ (Woodside 1976, cited in Huynh 2004, p. 6), literature has long been wielded as a ‘moral, educational and ideological tool’ (Healy 2013, p.2). Through a complex and often unconscious process of cultural osmosis, many Vietnamese women have adopted exemplary feminine traits embodied by the ideal woman that emerged from ‘a sea of literary characters in Viet proverbs, fables, books, plays and songs’ (Huynh 2004, p.6).

Confucianism has been upheld as the official Vietnamese state religion since the first period of Chinese domination in 111 B.C; its presence surged in the late 1800s under the Nguyễn dynasty, during which a twenty-two-volume code of Confucian ethics divided social life into ‘a yin-yang dichotomy’ (Huynh 2004, p.4). Consequently, predominant 19th century feminine characteristics are ‘socialized into the Vietnamese woman’s very genes’ (Huynh 2004, p. 6), surviving even periods of Western colonization through ever-popular proverbs conveying the Confucian notions of the three submissions and the four virtues “tam tòng tứ đức” (Huynh 2004, p. 9). While “tam tòng” dictates that a woman must obey three masters throughout her life: father [tại gia tòng phụ], husband [xuất gia tòng phu] and son [phu tử tòng tử]; “tứ đức" reminds her to fulfill her designated roles through the cultivation of four feminine virtues: diligence in domestic work [công], grace in appearance [dung], elegance in speech [ngôn] and modesty in principles [hạnh].

Since a female’s capacity for sentiments is measured by adherence to these teachings, constructed to instill endurance [chịu đựng], forbearance [nhẫn nhịn], and avoidance of conflicts [n��] - as illustrated in the folk song “Chồng giận thì vợ làm lành, miệng cười hớn hở rằng anh giận gì", Vietnamese women are vulnerable to moral disqualification if they do not embody the celebrated image of female subservience. Aside from the reputation of her patrilineage, ‘a female’s behavior reflects first on her mother’s morality’, prompting mothers to be complicit in the education (i.e. subjugation) of their daughters, or risk being condemned as an ‘incompetent role model’ and further emphasizing their inferior position within the household (Rydstrom 2002, p. 365). To avoid such criticism, Vietnamese girls and women have come to associate social acceptability with obedience to ‘repressive norms of ideal femininity’, ‘constructing their gendered subjectivities through self-surveillance’, facilitating their own subordination (Taylor 2013, p. 404; Bartky 2000, p. 328).

To quote ‘The Image of Women in Vietnamese Literature’ by novelist Công Huyền Tôn Nữ Nha Trang: ‘She was weak, ignorant, and prone to mistakes, thus she had to constantly depend on men’s wisdom to conduct herself. In order to reflect favorably on the honor of these men, she was most of all expected to uphold the ultimate values of virtue and chastity. The rationale for her subjugation was the conventional belief in the inferior nature of her sex’ (Cong 1973, cited in Duong 2001, p.210).

Vietnamese female warriors and the nationalist agenda

“Yet, there is an intentionality in the Vietnamese state’s remembrance of female heroism and sovereignty, a glorification of the past that imbues these rhetorics with patriarchal patriotism.”

Aside from a myriad of traditional role models characterized by virtuous embodiment of femininity, there is no shortage of strong, revolutionary women in Vietnamese history and stories. Vietnam’s prolonged struggle against foreign aggressors has fostered collectivism between men and women, generating a feminist narrative that challenges Western notions of individualism with the construction of a ‘communal self’ (Bulbeck 1998), diminishing the gender divide with collective prioritization of national independence.

Personified by real-life legends such as Triệu Thị Trinh, Trưng Trắc Trưng Nhị, Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai, and many other female revolutionaries, the collective identity of Vietnamese women is marked by ‘self-sacrificing martyrdom for the nation’s liberation/ decolonization’ (Duong 2001, p. 324). Women are portrayed as ‘heroines in war resistances and the economic development of Vietnam’ (Soucy 2000, p. 122) whose contributions are immortalized in stories and relics. Vietnamese children are familiarized with various tales celebrating the female patriotism of peasant ladies bludgeoning French soldiers to death with makeshift weapons and fearless women blocking American tanks with their own bodies. Perhaps the most well-known female warriors in Vietnamese history, the two Trưng sisters and Lady Triệu are deity figures of great national pride, known for commanding great armies against Chinese invaders on ‘mighty war elephants’ while ‘adorned in golden tunics’ (Huynh 2004, pp. 10-11).

The Vietnamese state also frames its national history as pro-feminism: claiming the original Vietnamese culture is rooted in Đông Sơn matriarchy, brandishing the Hồng Đức legal code during Emperor Lê Thánh Tông’s reign as evidence of long-established women’s rights, promoting stories about ‘pre-Neolithic female warrior remains found in North Vietnam’ wielding bronze staffs, measured at 6 ft tall (Soucy 2000, p. 121). All of these provide testimony that Vietnamese culture, despite ‘a millenium of patriarchal Confucian influences’ (Soucy 2000, p. 122), accords women with more freedom and power than their counterparts in male-dominated Chinese society.

Yet, there is an intentionality in the Vietnamese state’s remembrance of female heroism and sovereignty, a glorification of the past that imbues these rhetorics with patriarchal patriotism, thereby shifting ‘Confucian notions of female self-sacrifice and piety from the home to the nation’ (Duong 2001, p. 284). Through state manipulation, stories meant to empower women are turned into propaganda tools for national independence, constructed with ‘a patriarchal hierarchy of values that positions men unquestionably on top’ (Huynh 2004, p. 11) and strips heroines of their individual womanhood (*) (**). As Wendy Duong deftly elaborates: ‘by portraying feminists as female warriors or freedom fighters, one nobly legitimizes the sacrifice of women, the utilization of their labor and the ignorance of their individual cries for freedom of choice’ (2001, p.284). Furthermore, the brandishing of the Vietnamese matriarchal heritage can present the misleading proposition that ‘Vietnam has no need for a modern feminist movement’ (Duong 2001, p. 191). Ultimately, when the fight for women’s rights is merged with Vietnamese nationalistic agenda, feminism merely becomes ‘a Trojan horse for broader policy issues’, rather than a challenge to ‘the hegemonic masculine structure’ (Soucy 2000, p. 124).

(*) Triệu Thị Trinh who boldly declared “I want to ride the wind and walk the waves” is said to bear a womanly abhorrence for dirt and grime that made her fled a battle in disgust upon facing naked Chinese soldiers kicking up dust.

(**) In most retellings of The Trưng Sisters’ tale, the death of Trưng Trắc’s husband is the catalyst that ignited the sisters' innate nationalistic fervor, a detail likely manufactured to convince people who refuse to believe women could ever lead her husband into politics and battle. Also, when Trưng Trắc loses her nerves in the face of adversity, Trưng Nhị advises her to ‘shake off [those] ordinary female emotions and focus on military matters' (Huynh 2004, pp. 10-11).

Reinforcing traditional roles - Female self-sacrifice for the home and the nation

“Sayings like “đàn ông xây nhà, đàn bà xây tổ ấm” [men build houses, women build homes] are often cited not to promote gender equality, but to reinforce traditional gendered roles and resituate women within the home domains.“

While the representation of Vietnamese women as warriors and patriots aligns with ‘the Communist Party’s political priorities for national liberation’ (Scott & Truong 2007, p. 252), Vietnam’s agricultural and commercial labor forces also rely heavily on ‘female subservience as a socioeconomic liability’ (Tran 2002, p. 472; Soucy 2000, p. 121). Accordingly, the nation’s acknowledged respect for women’s heroic contributions in ‘overcoming poverty and backwardness to build the country’ is never separated from rhetorics urging them to ‘labor hard in the field and factory’ (Soucy 2000, p. 123).

A modern Vietnamese woman is thus instructed to embody the almighty Ms. Versatility in the slogan ‘Giỏi việc nước, đảm việc nhà" [proficiency in national causes, efficiency in managing the home]. Although this representation aims at confronting Confucianist and feudal tendencies to undervalue women, it is intrinsically contradictory in its depiction of women ‘as laborers and freedom fighters’ and simultaneous maintenance of ‘pre-eminent traditional roles and responsibilities’ (Soucy 2000, p. 123). The encouragement of Vietnamese women to ‘increase economic production’ and display ‘obedient patriotism to the government’ ultimately echoes Confucian sentiments that enforce ‘a gendered division of labor’ and ‘a habitus of inequality masqueraded as proper behavior’ (Duong 2000, p. 264; Soucy 2000, p. 124).

Ramifications of the historical centralization of female roles in domestic vocation persist even in today’s society: women are often limited to ‘labour-intensive industries’ or skilled works that are ‘associated with feminine characteristics’ (Nguyen 1999, p. 50). Gender-based occupational role differentiation is maintained in everyday setting through the notion of personal face “thể diện" . Contrary to the unexamined nature of female personal face, “thể diện đàn ông” or the male face, must be protected and complemented by the women surrounding him; fulfillment of this responsibility seems to be the only expectation for female “thể diện" (Nguyen & Simkin 2015, p. 4).

Informed by the Vietnamese sexist tendency to “trọng nam khinh nữ" [respect men, disrespect women], the most prominent connotation of “thể diện đàn ông” dictates that ‘a man must not be inferior to women’, especially his wife (Nguyen & Simkin 2015, p. 4). Society is critical of women who ‘attempt to increase their professional, social or political mobility’ (Schuler et al. 2006; Nguyen 2013; cited in Nguyen & Simkin 2015, p. 1). Sayings like “đàn ông xây nhà, đàn bà xây tổ ấm” [men build houses, women build homes] are often cited not to promote gender equality, but to reinforce traditional gendered roles and resituate women within the home domains. In addition, “thể diện" asserts men as the breadwinner and financial backbone of the family, thereby ‘contributing to lower mutuality of expected support among men and women’ as men must do important jobs ‘outside in society’, not stay at home to assist his wife in menial chores (Nguyen & Simkin 2015, p. 4).

The pervasiveness of “thể diện" as a reflection of morality reinforces ‘the naturalness of gender inequality regarding women’s roles and responsibilities’; additionally, fear of public sanctions against nonconformity fosters a tolerance for double standards and discrimination (Nguyen & Simkin 2015, p. 8). Drawing on these concepts, Vietnamese literature pressures women into accepting their ‘socially prescribed roles’ (Chafetz 1974, p.3) as compliant, self-sacrificing background characters for men ‘whose Confucian path was to rule the nation and then pacify the world’ (Tran 2002, p. 474) through stories such as Lưu Bình & Dương Lễ (***) and The Tale of Lady Kiều.

While the absolute subservience and chastity of Châu Long (in LB&DL) encapsulate ‘the traditional image of the Vietnamese woman as ‘a chattel, a loyal wife and reluctant seductress’ (Huynh 2004, p.8); Kiều stands at the ‘pinnacle of exemplary Vietnamese femininity in both a Confucian and Buddhist sense’ (Huynh 2004, p. 8) as a self-sacrificing woman who sells herself into prostitution in order to ‘ransom her father from imprisonment’ (Jacklin 2010, p.178). Both these virtuous, exceptional ladies have wholeheartedly dedicated themselves to the ambitions and wellbeing of the [mediocre] men in their lives, sending the message that no matter how accomplished a girl is, her social position and every decision will be overshadowed by those of men.

(***) Lưu bình & Dương Lễ”: a folk story in which the wife (Châu Long) of a mandarin (Dương Lễ) exhibits extreme female self-sacrifice and endurance by complying with her husband’s request that she lives in a small hut with his best friend (Lưu Bình) for two years, supporting this man with her low-paid silk weaving, while he studies to become a scholar.

Hồ Xuân Hương - the liberal feminist voice in classical literature

“Throughout the expansive history of Vietnamese literature, during which it has been utilized as ‘a powerful advocacy tool for justice’, there exist substantial cultural texts that provide candid expressions of womanhood and female empowerment.”

Offering a ‘uniquely bold and potently erotic' voice of ‘a liberal female in a male-dominated society’ into a private Vietnamese past (Tran 2002, p. 471), Hồ Xuân Hương (****) (hereafter: HXH) is a champion of womanhood and prominent fighter for women’s liberation. Uniformly classified as feminist in nature, HXH’s entire bibliography is dedicated to tearing down the ‘patriarchal double standards, Confucian teachings and institutionalized oppression’ inflicted upon Vietnamese women (Huynh 2004, p. 12).

(****) Hồ Xuân Hương (1772–1822): Dubbed as "The Queen of Nôm poetry", she is considered to be one of Vietnam's greatest classical poets.

HXH dares to dispute contemporary taboos through depictions of ‘the female body as a sex object at the mercy of men’ (The Jackfruit, The Snail), criticizing ‘male selfishness and lack of finesse in sexual encounters’ (Tran 2002, pp. 474-475) while alluding to the female sexual prowess capable of bringing ‘kings, mandarins, monks, scholars and moralists’ alike down to Earth (The Wayward Monk, The Incredible Grotto, Quán Sứ Pagoda) (Duong 2001, p. 213).

Writing about women’s subordinate roles as domestic laborers, wives and mothers, HXH ‘turns these chores around to imply women’s agency’ (Bailing Water, Weaving at Night) while highlighting the sacrifices women make in everyday life to please her family (The Burdens of Husband and Child) (Tran 2002, pp. 482-483).

Victimized by Confucian traditions and a polygamous society, HXH laments the ‘insecurity, sadness and anger’ associated with women’s low status within society through a series of poems entitled Self-Confession [Tự Tình] (Tran 2002, p. 486). In Self-Confession 1, HXH uses the image of a drifting boat without a helmsman to bemoan the inevitable female dependence on men’s leadership. In the second and third confession, she moves from discussing the ‘social and personal pressures for marriage’ to speaking out against the polygamy system that exploited minor wives as sexual outlets and unpaid labor (Tran 2002, p. 487). HXH also savagely mocks Cen Yidong (Temple for the Governor) whom she viewed as undeserving of a sacred temple; suggesting that had she been born a man and not excluded from the patriarchal mandarinate and military services, she would have righteously garnered more admiration than this Chinese general.

In her most famous stanza The Floating Glutinous Rice Cake [Bánh Trôi Nước], HXH praises the ‘stoic ability of women to subsist and subvert from within’ (Huynh 2004, p. 11), using the double-meaning of the formless, hand-molded rice cake to allude to the sexual exploitation of ‘female breasts, pressed into the service of men’ (Tran 2002, p. 489) and the ever-changeable position of a woman with ‘no imminent prospect for betterment’; HXH thus advises women to nurture ‘the crimson soul inside’ (red bean filling) - a symbol of untainted morality and femininity despite ‘infliction of indignity upon womanhood' (Duong 2001, p. 205).

The Vietnamese message for women to negotiate and compromise ‘the patriarchal scripts that regulate gender roles’ within their sociocultural constraints (Pande 2015) is no less inspirational or feminist than the ‘shouts for free speech, pro-choice and equal pay’ in Western countries (Duong 2001, p. 205). The defiance and individuality in HXH’s poems prove the existence of ‘women in traditional Vietnamese society’ who confronted the Western view that Asian women have always been ‘submissive to the authority of their fathers and husbands’ (Duong 2001, p. 205).

Subverting traditional femininity - The role of Vietnamese folk and modern literature

In traditional Vietnamese society, female sexuality is suppressed by precepts such as ‘nam nữ thụ thụ bất thân' [men and women shall remain physically distant] and Confucian doctrines which condemn ‘premarital sexual intercourse, pregnancy out of wedlock, divorce and abortion’ as immoral ‘social evils’ (Rydstrom 2006, p. 284). The female body is further desexualized by its ‘heaven-mandated natural vocation’ to be a mother and maintain the race (Mai 1997, p. 311), a notion that ‘reduces female sexuality to the mere function of reproduction’ (Yurval-Davis 1997, cited in Rydstrom 2006, p. 287).

It is in this setting that HXH’s poetry, ‘full of sexual innuendo and sensual images’ received the ‘cultural collective stamp of approval’ from the common people to combat the suppression of female sexual identity (Duong 2001, p. 214). Vietnam’s folk literature echoes HXH’s outspokenness: folk songs like “Không chồng mà chửa mới ngoan/ Có chồng mà chửa thế gian sự thường" and “Lẳng lơ mà chết cũng ra ma/ Chính chuyên mà chết cũng khiêng ra đồng" denounce ‘the hypocrisy of love in wedlock and sexual abstinence’, claiming there is no distinction between promiscuous and pious women who would all die one day (Duong 2001, p. 214). The ancient folk voice directly confronts Confucian literature: poking fun at polygamous males who deserve ‘to sleep in pig’s farms’, promoting an ‘egalitarian division of labor’ in rice fields and fishing villages, belittling male supremacy and unabashedly expresssing ‘love, romanticism and freedom in dating/ mating’ (Duong 2001, pp. 214-215).

Condemned by her contemporaries as ‘anarchical and obscene’, HXH’s poetry nonetheless remains in popular circulation in modern day Vietnam, neither taught publicly in schools nor ‘sanitized by bureaucrats’, but disseminated by young women ‘through hushed whispers in all its intended filth and wisdom’ (Huynh 2004, pp. 12-13; Tran 2002, p. 491). In a time of globalization and Doi-moi Renovation, the cheeky tone and early awareness of Vietnamese classical and folk literature are amplified by people’s increasing acceptance of ‘global commodities, urban magazines and Western-imported goods’ (Rydstrom 2006, p. 283) to encourage manifestations of female sexuality in present-day Vietnam. In particular, young girls from Vietnamese rural areas whose sexual identity has been more severely suppressed than their urban counterparts are now exposed to the effects of globalization, new migrant trajectories and the enormous ‘socioeconomic gap between First-World luxury and Third-World poverty’, actively participating in sex-work to attain improved wealth, class status and social mobility (Hoang 2015, p. 159).

Considering Vietnam’s prolonged history of colonization, Vietnamese women are also enabled by ‘the complex interaction between 19th century Vietnamese Confucianism and 20th century Franco-Vietnamese ideals’ to debate, customize and adopt some Western notions of individualism and liberalism (Huynh 2004, pp. 4-5). During this period, the most popular literary works were created by the Self-Strength Pen Club [Tự Lực Văn Đoàn], whose biggest contribution to the feminist agenda was its ‘voicing of the middle class' yearning for radical change and freedom of choice’ (Duong 2001, p. 270).

The Pen Club’s most enduring work Breaking The Ties pleads for the ‘justice and expediency of the new’ over ‘the tyranny and futility of the old’ (Huynh 2004, p.15), telling the story of Loan, a Western-educated woman who is forced to marry into a traditional family and suffer ill-treatment at the hands of her mother-in-law. Her loveless marriage ends when Loan is taken to court over the accidental murder of her husband (Duong 2001, p.271). When the prosecutor accuses Loan of being ‘blinded by romanticism’ and neglectful of her ‘heaven mandated role as the pillar of the family’ like the virtuous women in old Vietnamese society, Loan’s attorney makes the scathing response: ‘the only thing she is guilty of, is going to school trying to develop her intellect and become a new person, then return to live with old-fashioned people’ (Huynh 2001, pp.16-17).

However, the Pen Club’s most fundamental flaw is their lop-sided view of liberation, portraying it as a conflict between ‘the old system of matriarch and Western individualistic ideas’ (Duong 2001, p. 271), attempting to apply a universal liberal notion of social justice to Vietnam instead of developing a framework of ideas specific to the nation’s culture and history.

Conclusion

The cultural identity of Vietnamese womanhood is markedly influenced by the nation’s history, folklores and classical literature, including a repetitive and prolonged period of warfare and collective sufferings, whereby women have been portrayed as ‘martyrs, national treasures and laborers both in war and in peace’ (Duong 2001, p. 191). As demonstrated by the epigrams and literary models endorsed by the Vietnamese state and society, women are restricted by ‘foreign rules and economic exploitation’ just as much as they are dominated by ‘locally entrenched patriarchies and traditional structures’ (Duong 2001, p. 283). Yet, throughout the expansive history of Vietnamese literature during which it has been utilized as ‘a powerful advocacy tool for justice’, there exist substantial cultural texts that provide ‘candid expressions of womanhood’ and outline a subtle yet ‘radical feminist agenda’ (Duong 2001, p.205). When tracing feminist ideas in Vietnam, one must look beyond the voices of nationalists and martyrs to hear the advocates for individual freedom, and acknowledge the nuances of Vietnam’s cultural history so as to avoid incompatible applications of Western frameworks.

References

Bartky, S.L. 2000, ‘Body Politics’, in Jaggar, A.M. & Young I.M. (eds.), A Companion to Feminist Philosophy, Blackwell, Malden, pp. 321-329.

Bulbeck, C. 1998, ‘Individual Versus Community’, in Reorienting Western Feminisms: Women’s diversity in a postcolonial world, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 57-96.

Cameron, D, 2006 'Performing Gender Identity: Young Men's talk and the Construction of Heterosexual Masculinity' in The Discourse Reader, Routledge, New York, pp.419- 422.

Chafetz, J.S, 1974, Masculine/Feminine or Human?, F.E Peacock Publishers, Inc., Illinois.

Cong, H. T. N. N. T 1973, The Traditional Roles of Women as Reflected in Oral and Written Vietnamese Literature, Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

Duong, W. N. 2001, ‘GENDER EQUALITY AND WOMEN'S ISSUES IN VIETNAM: THE VIETNAMESE WOMAN-WARRIOR AND POET’, Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 191-324.

Healy, D. 2013, ‘New Voices: Socio-Cultural Trajectories of Vietnamese Literature in the 21st Century’, Asian and African Studies, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2013.

Hoang, K. K. 2015. ‘Sex Workers’ Economic Trajectories’ in Dealing in desire: Asian ascendancy, Western decline, and the hidden currencies of global sex work, University of California Press, Oakland, California, pp. 154-172.

Horton, P. 2015, Note passing and gendered discipline in Vietnamese schools, British Journal of Sociology of Education, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 526-541.

Jacklin, M. 2010, ‘Southeast Asian writing in Australia: the case of Vietnamese writing’, University of Wollongong: Faculty of Arts Papers, pp. 175-184.

Nguyen, N.T. 1999. ‘Transitional economy, technological change and women's employment: The case of Vietnam’, Gender, technology and development, vol. 3, no. , pp. 43-64.

Nguyen, T.Q.T. & Simkin, K. 2015, ‘Gender discrimination in Vietnam: the role of personal face’, Journal of Gender Studies, 1-9.

Rydstrom, H., 2001. ' “Like a white piece of paper”, Embodiment and the moral upbringing of Vietnamese children’. Ethnos, vol. 66, no. 3, pp.394-413.

Rydstrom, H. 2002, ‘Sexed bodies, gendered bodies: children and the body in Vietnam”, Women’s Studies International Forum, vol. 25, no.3, pp. 359-372.

Rydstrom, H. 2006, ‘Sexual desires and ‘Social evils’: young women in rural vietnam’, Gender, Place and Culture, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 283-301.

Scott, S. & Truong, T. K. C. 2007, ‘Gender research in Vietnam: Traditional approaches and emerging trajectories’, Women’s Studies International Forum, vol. 30, pp. 243-253.

Soucy, A. 2000, ‘Vietnamese warriors, Vietnamese mothers: state imperatives in the portrayal of women’, Canadian Woman Studies, Vol. 19, no.4, pp. 121-126.

Taylor, D., 2013. ‘Toward a Feminist “Politics of Ourselves”’, A Companion to Foucault, pp. 401-418.

Tran, M. V. 2002, ‘Come on, Girls, Let’s Go Bail Water’: Eroticism in Hồ Xuân Hương's Vietnamese poetry’, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 471-494

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Critical Analysis | Media, Film, Culture

Korean and Japanese Horror Cinema: Transnational Impact, Cultural Specificity, and Contending with National Anxieties (2021)

Throughout the early 2000s, Korean and Japanese horror cinema (hereafter: K-horror and J-horror), became known to global audiences under the monolithic Asia Extreme brand (Math, 2012). While Asia Extreme garnered high-profile statuses for K-horror and J-horror, it did so through reductive Orientalist perceptions that separate 'grotesquely sexual/ violent East Asian horror' from the established Western paradigm (Lee, 2011, p.121). The transnational influences and Hollywood conventions that informed K-horror and J-horror's development are unavoidable considering both countries' history with the U.S. However, this paper sets out to establish the cultural specificity of K-horror and J-horror, that is enhanced, rather than diminished, by their hybridity. Amongst the discussion is how horror cinema articulates anxieties about 'the loss of tradition in the face of encroaching modernity', as well as the link between urbanization, isolation, and death (Byrne, 2014, p.191). A major finding is that responses to socioeconomic transition find expressions in extreme cinema, specifically in the 'monstrous feminine' imagery that serves as the binding thread between Japanese and Korean narrative forms.

(**) This paper examines historical contexts and cultural traditions that manifest in the media content of two East Asian countries, similar in their Confucianist beliefs and relationship with the U.S. The study only analyzes well-known and not-so-recent works within a specific genre, horror. Further reading on media history would benefit the author's social, gender-studies leaning analysis.

Full PDF

HOW K-HORROR IMBUES BORROWED CONVENTIONS WITH CULTURAL SPECIFICITY

During the economic crisis of 1997, South Korea was rescued by the International Monetary Fund, which opened Korean economic, political and cultural life to outside interference. The Segyehwa globalization project triggered the Korean Wave Hallyu by adhering to Western methods of production (Cagle, 2009, pp.127-8). Some have argued that modernization can ‘trigger the loss of tradition and cultural identity’; while others worry about ‘the inadequacy of Western narrative forms’ to accommodate Asian desires and anxieties (Cagle, 2009, p.129). Although K-cinema indeed utilizes Hollywood’s stylistic devices, it retains unique cultural flavors through the incorporation of Confucianist teachings and the melodramatic dimension that reflects Korea’s history of trauma.

HAN & MELODRAMA: NEW DIMENSIONS OF ‘GROTESQUE’

“This decision reflects the K-horror reversal of moral structures, whereby malicious entities are those who suffered the most, and victims turn out to be past transgressors.“

The K-horror genre is embedded in melodramatic plots and colored by han, or grief over continual and undeserved suffering. These two components infuse Korean cinema with a pervading sadness that not only caters to local sensibilities but also distinguishes K-horror from Western or Japanese horrors (Martin, 2014, p.426). Han is a national trait unique to Korea that arises from decades of suppressed anger (Cagle, 2009, p.130). To find their expression in extreme cinema, han messages must be ‘converted into visual or sonic glitches’. The results are violent outbursts in South Korean films, imbued with hidden meaning, that might not translate to a Western audience; this explains why American critics are quick to condemn films like Oldboy (2003) as ‘overly grotesque’. In actuality, K-horror rarely conforms to Hollywood’s deployment of violence. The ghosts and killers of K-horror make careful selections of victims based on past crimes in order to re-establish the moral order. As a result, rather than scorned, the damaged and disturbed are sympathized; rather than fear, tales are saturated with sadness (Math, 2012).

Another distinctly Korean convention is ambiguity, moral-wise, plot-wise. The infamous final scene of Oldboy, in which Dae-su responds to Mi-do’s embrace with an expression that morphs between laughter and sobs, is full of melodramatic properties and lacking in resolution (Ma, 2017, p.170). Since a primary function of han is the meditation of residual trauma, unresolved endings are apt metaphors for Korea’s contentious relationship with the past (Cagle, 2009, p.126). The aversion to tidy closures and binary moral definitions is what makes K-horror so horrifying to Western audiences. Whereas Hollywood endings reinforce the idealized American dream, K-cinema displays ‘a more reflexive perception of its nations’ self-image’ (Cagle, 2009, p.126).

GENDER SENSITIVITIES SPECIFIC TO KOREAN LORE AND BELIEF SYSTEMS

A ‘thrice-told tale transnationally’ across Japan, Korea, and America , Oldboy also provides a study of how East-West cultural dynamics fuse with Confucianist gender constructions (Ma, 2017, p.159). Despite mirroring the Greek tale Oedipus, a classic tale of ‘nature mocks at morality’, Oldboy manages to convey a specific brand of Korean masculinity. Dae-su, whose Eastern social codes have little tolerance for individual lapses, cuts off his tongue to atone for his crime of incest, instead of shirking it off to Western modes of contamination (hypnosis) (Ma, 2017, p.163). In fact, embedded within K-horror is a cache of culturally specific fears and beliefs; Martin (2014, p.427) regards K-horror’s very emergence as ‘a continuation of traditional mythos’.

For example, a retelling of the classic tale Janghwa and Hongryeon, A Tale of Two Sisters (2003) is hybrid in its Confucianist sensibilities and Victorian aesthetics. Some would classify Two Sisters as a gothic horror based on its psychological undertone, and the fact that much of the drama unfolds within a claustrophobic household. Yet, the film clearly has its roots in Korean pre-cinematic horror tropes, reflecting the 1960s cinema of gumiho and wonhon, of female rage, twisted bonds, and trauma relived through flashbacks (Martin, 2014, p. 427). Meanwhile, the 2008 high-school horror Death Bell contains undeniable Hollywood influences, yet deviates from typical slasher-film endings. Instead of Ina, from whose point-of-view we’ve been navigating through the gory killings of students and teachers, Death Bell establishes Ji-won, the wonhon at the center of these vengeful acts, as the ‘final girl’ (Shin, 2013, p.138). This decision reflects the K-horror reversal of moral structures, whereby malicious entities are those who suffered the most, and victims turn out to be past transgressors. In addition, Death Bell highlights the dimension of han motivating these horrific murders, reinforcing the wonhon’s role as a ‘symbolic reaction against the oppression of the Other‘ (Martin, 2014, p.426). K-horror thus utilizes and subverts transnational conventions to better convey socio-historical contexts and gender relations.

JAPAN’S AFFECTIVE HORROR: A CINEMA OF HYBRID MEDIA AND LONESOMENESS

“The apprehension towards urbanization, self-induced alienation, and the loss of sway over younger generations, find an outlet in J-horror projects critiquing city life and the tech regime.“

Having examined the cultural distinctions of K-horror, this paper will attempt to do the same for Japanese horror cinema. Korea is not the only society that has been impacted by U.S. intervention and ideologies. According to McRoy (2005, p.177), the ‘symbiotic relationship between Japan and the U.S.' can be observed in motion pictures. Behind the 90s classics that established J-horror's global brand name are directors like Nakata (Ringu, Dark Water), Shimizu (Ju-On), and Kurosawa (Loft), who all cite American and European cinemas as their influences (Kinoshita, 2009, p.105). Most notably, Ju-On's straight-to-DVD precursors contain both elements of U.S. slasher films (Nightmare on Elm Street; Friday the 13th) and the kaidan genre (Onibaba, 1964; Kwaidan, 1965) (McRoy, 2008, p.77). Commentators have tried to attribute J-horror's international appeal to its lack of distinctive cultural features. While Japan indeed emulates Hollywood filmmaking, McRoy (2008) argues that, rather than diluting its essence, this transnational hybridity enhances ‘the Japanese-ness of J-horror’ (McRoy, 2008). The meshing of U.S. and Japanese influences captures the ambivalence toward both a Westernized modernity and the return to conservative traditions (Lee, 2011, p.123).

A REGIME OF FRAGMENTARY SPECTATORSHIP

To articulate these anxieties, J-horror often deploys the 'human alienation caused by technological mediation' trope, alongside dangerous females and dysfunctional families (which the next section explores) (Kinoshita, 2009, p.106). J-horror's fascination with digital technology began during the 1989 economic decline when all levels of production underwent reconfiguration (Wada-Marciano, 2007, p.24). J-horror's emergence parallels the rise of the DVD market and increased collaboration between independent filmmakers and major studios. This fortuitous combination helped kickstart J-horror's compatible relationship with new media, enabling it to bypass costly theatrical releases and rigid content regulations. DVD serialization induced a cycle of horror films that embodies 'excessive art' in all its glory. From then on, program pictures satisfied all three prongs of production, distribution, and reception, which contributed to economic stabilization (Wada-Marciano, 2007, p.25). Japanese exported films were a lucrative business, amongst which horror movies, placed at the forefront of the Asia Extreme phenomenon, held universal appeal. Even promoted under an umbrella term and accused of merely exaggerating Hollywood conventions, J-horror is distinguished in its sensibilities and narrative devices (Wada-Marciano, 2007, p.38).

The warning that technology is dangerous and isolating pervades a great number of J-horror movies. Japanese filmmakers utilize the affordances of these technologies to convey anxieties about media distortions (Richardson, 2012, p.14). As can be observed in the home video aesthetics of Ringu, corrupted footage can blur the lines between the video world and real life, robbing us of our objectivity. In addition, J-horror pushes the limitations of photo-based media to ‘render the living and the dead’, the known and unknown (Kinoshita, 2009, p.114). Imprinted on our minds are representations of ghostly entities via obscured faces, ominous silhouettes, and indiscernible glitches. This ‘regime of fragmentary spectatorship’ enhances not only the delivery of horror films but also their psychological resonance (Wada-Marciano, 2007).

J-HORROR’S CINEMA OF SENSATIONS

To elaborate, central to J-horror aesthetics is the horror aftertaste (shinko ni kowai) and preoccupation with psychological fears. Unlike most horror movies that seek to shock and surprise, Japanese horrors focus on inducing a persistent dread-filled affect through a ‘cinema of sensations’ (Brown, 2018). Dark Water (2003) masters this through the heavy wetness and desolation of its crumbling mise-en-scene. The premise of a mother sacrificing her life and leaving behind her daughter to appease a lonely child ghost is haunting in its resignation. Dark Water resonates with our fear for future generations, subjected to ‘impending cycles of abandonment and neglect’, the result of disintegrating familial structures (McRoy, 2008, p.86).

Rivaling K-horror’s reputation for ambiguity, J-horror is also known for its non-linear narratives and resistance to Hollywood endings. Specifically, amongst the final scenes of Audition (1999) is Aoyama’s love-making memories with Asami, before she comes out as a deranged murderess. The movie should have ended here to adhere to the ‘it was all a dream’ device. Instead, this brief respite is intercut with Asami’s sing-song chant of ‘kiri kiri’ as she continues to inject needles into Aoyama’s body (Cagle, 2009, p.125). Watching Audition, we struggle to decipher whether the torture sequence is only Aoyama’s nightmare, or if the reality is so horrible that he must retreat into his mind. The surreal, accumulating dread is achieved through lighting, as the color scheme shifts from cool blue (Aoyama’s coded color) to orange and red (for Asami’s sadistic side). The combination of Asami’s hair-raising mantra (sonic) and the disorienting shifts in lighting (visual) not only conveys the ‘porous boundaries between reality and hallucination’, but also exemplifies Japan’s cinema of sensations, capable of transporting us from hope to panic within seconds (affect) (Brown, 2018, p.246).

NEW MODES OF LIVING & FRACTURED IDENTITIES

In line with treacherous technology, a key theme across J-horror (and K-horror) is the link between urbanization, isolation, and death. Dark Water, Ringu, and Ju-On all place women within isolated apartments, severed from the nuclear family, and faced with the abject (Kinoshita, 2009, p.107). The majority of J-horror is situated in the megalopolis of Tokyo, and portrays city dwellers in cheap, drab apartments at the intersection between ‘privacy and publicity, domesticity and urbanity’ (Lee, 2013, p.102) (Wada-Marciano, 2007, p.26). Enhanced by ‘geographical determinism’, Japan’s isolation as an island country has fostered ‘social ideologies privileging both hierarchy and community’ (Davies & Ikeno, cited in McRoy, 2008, p.107). Weaned on new media and transnational influences, young people increasingly move to big cities and neglect face-to-face communication; their independence-centered modes of living clash with conservative factions. The apprehension towards urbanization, self-induced alienation, and the loss of sway over younger generations, find an outlet in J-horror projects critiquing city life and the tech regime. Linking back to Japan's anxieties about its permeable social body, Kinoshita (2009, p.119) defines urban settings as ‘homogenized spaces that undermine the stability of a nation’s geographic identification’.

THE ‘MONSTROUS FEMALE’ AS A SITE FOR CONTENDING WITH NATIONAL ANXIETIES

Distinct cinemas they may be, J-horror and K-horror share an acute sensitivity towards gender and psychosocial dynamics, exemplified in the wide range of films centered on female victimization and vengeance. According to Lee (2011, p.123), the 'feminine Other' archetype serves to articulate anxieties over the clash between age-old Confucianist traditions and increasing Western impact on social formations in Japan and Korea.

“Both cinemas, rooted in patriarchy, project anxieties about socioeconomic transformations onto the female body, resulting in the age-old 'monstrous feminine' archetype, the wonhon and yurei that must be subdued, in folk tales, movies, and possibly real life.”

JAPAN’S BREAKDOWN OF NORMATIVE FAMILIES: DEVIANT WOMEN & FRACTURED MASCULINITY

The Japanese economic transition, underpinned by U.S. ideologies, influenced the abolishment of Family Law in the 1950s, which in turn led to the collapse of hegemonic gender norms. Robin Wood conceives the family as ‘a unifying master narrative’ across horror cinema; and since Japan’s marriage reform resulted in increased divorce, the resistance against socioeconomic transformations finds convenient expression in single mothers. Marked by their marital statuses, Reiko from Ringu (1998) and Yoshimi from Dark Water (2003), are both susceptible to supernatural encounters (McRoy, 2008, p.76). These haunting J-horror classics thus establish deviant females as a threat to the social cohesion of ‘the masculine national subject’. Japan has long deployed the ‘monstrous feminine’ imagery to scapegoat its problems, from the lank-haired specters of urban legends to contemporary representations of terrifying females. Audition, for example, blames Japan’s bleak future and corrupted gender relations on ‘the dearth of decent women’, as the widowed Aoyama falls in love with soft-spoken Asami who is in fact the face of horror (Brown, 2018, p.222). The first All Night Long movie (1992), set during the 1980s economic recession, features three deadbeat schoolboys who reassert their dominance through sexual violence and presents another case of women having to carry the trauma of damaged masculinity (McRoy, 2008, p.116). As J-horror demonstrates, almost every social issue can be attributed to deviant females, from the disintegration of normative families and motherhood to crushed male egos and youth apathy (Dumas, 2018, p.29).

KOREA’S PATRIARCHAL OPPRESSION & MONSTROUS MOTHERHOOD

In much the same manner, Korea’s reverence for mothers slides easily into fear; at the center of many a K-horror project are evil mother figures: ‘stepmothers, mothers-in-law, even sacrificing mothers’ (Oh, 2013). The titular character in Mother’s Grudge (Eommaeui han, 1970), Soo-im, is a typical victim of Confucian patriarchy, one who is filled with han, suffers a wrongful death, and returns as a wonhon to enact revenge. The cause of her tragedy and the engine powering the story is Soo-im’s defiance of Confucian teachings which promote female subservience even in the face of blatant injustice (Oh, 2013, p. 61). In A Tale of Two Sisters, the nurse-turned-stepmother Eun-joo represents the disruptive agent that tears apart Su-mi and Su-ryeon’s nuclear family. On the other hand, Su-mi’s descend into psychosis following her dad’s affair is a symptom of familial and patriarchal oppression (Wing-Fai, 2013, p.178). The synchronized menstrual cycles of stepmother and daughters at one twisted point signal the convergence of three characters into a unified ‘force of feminine excess’, which according to Clover (1992) ‘triggers male fear of castration’ (Wing-Fai, 2013, p.179). In both Mother’s Grudge and Two Sisters, the women are at once, the oppressed and oppressor, at once, the victim and agent of Confucianism. These representations of female relationships are specific to Korea’s adoption of patriarchal beliefs, and mirror J-horror’s anxieties over the male loss of control.

Despite nuanced depictions of female suffering, classic horror cinema almost always ends badly for defiant women, no matter how society fails them. When adolescent girls randomly turn into man-eating zombies in the Japanese horror-comedy Stacy (2001), they must be exterminated by fathers, husbands, and male figures. Richardson (2012) calls the Stacies ‘the embodiment of female oppression and male aggression’, an age-old combo that is repeatedly reinforced through female defeatist horror motifs. In Woman’s Wail (Yeogokseong, 1986), the wonhon of a murdered mother almost succeeds in slaughtering her treacherous husband’s entire bloodline when she perishes from an absurdist exorcism. Made during Korea’s pursuit of accelerated development (1980s), Woman’s Wail reveals how social anxieties get purged through ‘the expulsion of dangerous females’ (Hwang, 2013, pp.81-82). Whether an allegory for real life or not, J-horror and K-horror’s resolution for the ‘monstrous feminine’ lies in death and subordination, followed by the restoration of masculine power.

CONCLUSION