Text

saint catherine’s monastery

sinai peninsula, egypt

14.11.2022

#it was so amazing here. i couldn’t photograph any of the interior/any icons but it was stunning#if you ever have the chance to go here definitely hike mt Sinai for the sunrise then go to the monastery. it’s breathtaking#St Catherine’s monastery#monastery#eastern orthodox#Egypt#original

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pilgrim’s cloak of Stephen III (1544-1591)

Leather / shell

GERMANISCHES NATIONALMUSEUM

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

cloistercore is so cool i wanna join the monkosphere

hell yes brother. i clear a space in the scriptorium for you

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

#a really interesting read. seems to be documenting a slow change from medieval to early modern/modern ideas of race#emphasis still on religious difference but with skin color playing an increasing role symbolizing this visually#medieval history#articles

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

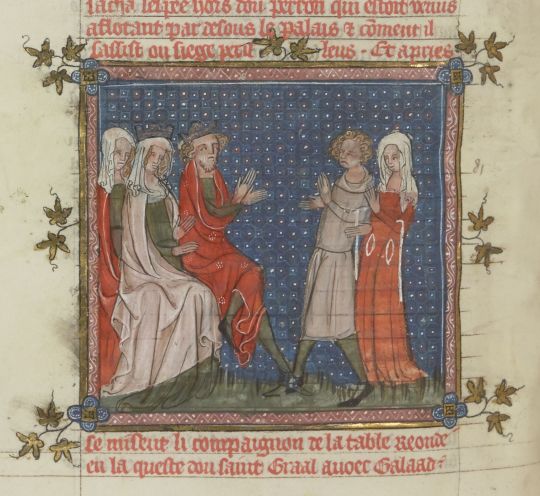

Illuminated manuscript of Lancelot du Lac, 1344-45, Flemish

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

Martin Schaffner, The Last Judgement, 1496-1499, Augustiner Museum

#German medieval and early modern art is well known for its instense emotionality in expressions. seen again with 20th c German expressionist#the last judgement#medieval art#alterpiece#the tears in the eyes are my favorite. i love the depiction of tears in art#will post more from this museum

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#yeah this belongs here#maybe hide the food in some sort of wrapping and god won’t notice you’re eating#monastic memes

589 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval monk who's only ever read the Bible reading his second book: Getting a lot of Bible vibes from this...

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

tumblr university is OUT tumblr monastery is IN brother tumblrinus is painstakingly copying out the most interesting prev tags on a manuscript of vergil until the abbot calls him out for not making his proto-gothic script accessible enough and also for his heresies

113K notes

·

View notes

Text

drinking red wine straight from the source (jesus’ side wound)

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

so i dont read a ton of environmental history but Paolo Squatriti’s Landscape and Change in Early Medieval Italy: Chestnuts, Economy, and Culture is a great look at the way humans shape and are shaped by the natural environment that also makes me feel super emotional about chestnut trees

also it’s definitely a seasonally appropriate book, given autumn is the time of year when the chestnuts are bountiful

0 notes

Text

definition of a pussy out kinda look

attis / trier / 2nd century CE / rheinisches landesmuseum

#this is 2nd century so not really medieval but it gets a pass for fucking so severely#also yes it’s a penis not a pussy…the fit is gender neutral though#fashion history#Roman fashion#medieval fashion#original

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hebrew inscriptions on the ceiling of the Medieval Jewish Prayer House show a bow and arrow with a prayer for peace, and a Star of David with the priestly blessing. Budapest, 1364.

345 notes

·

View notes

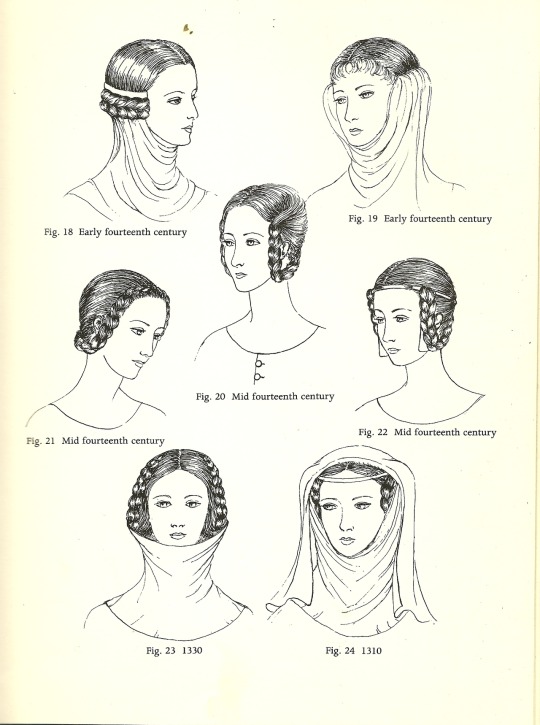

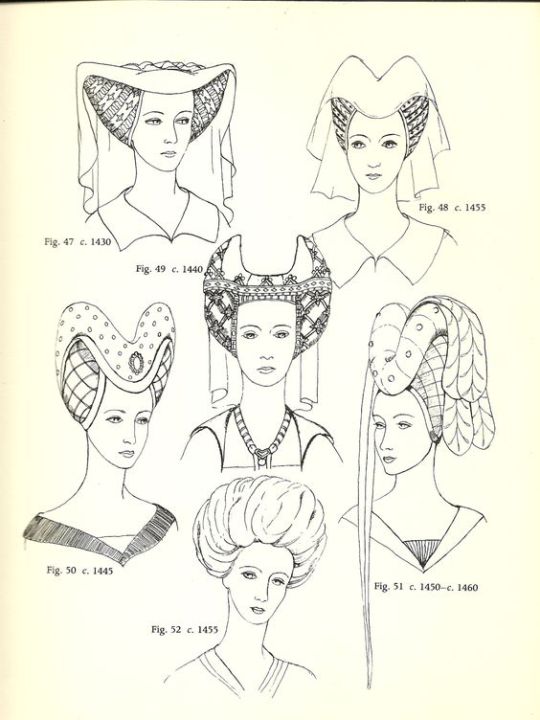

Photo

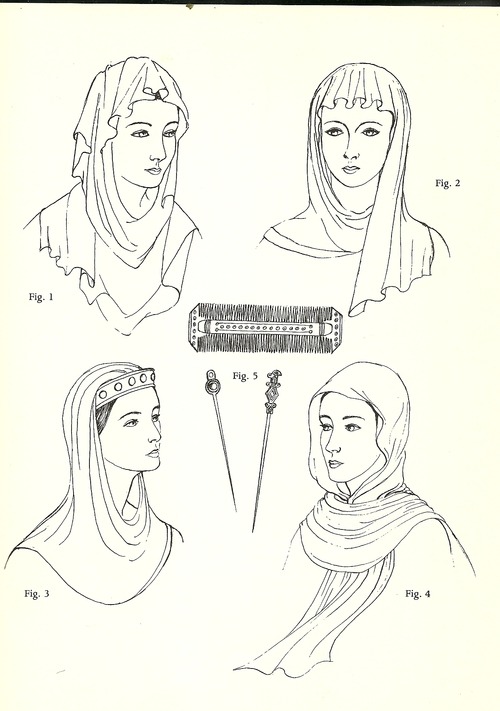

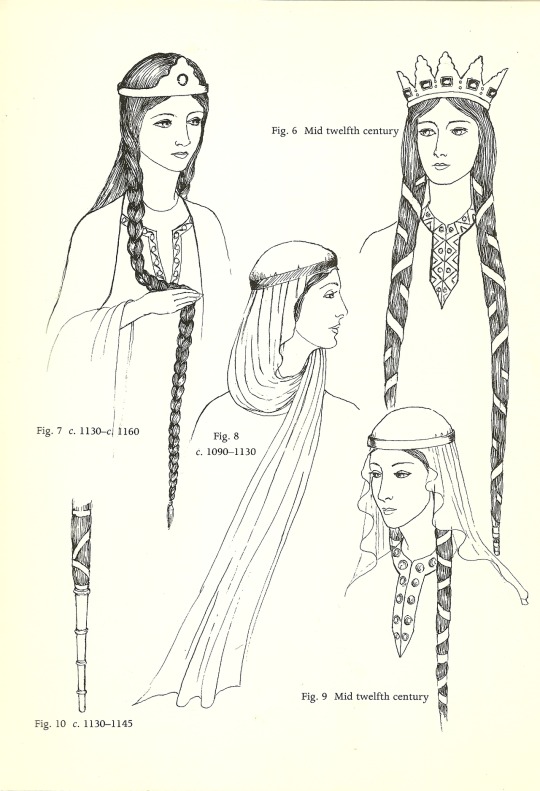

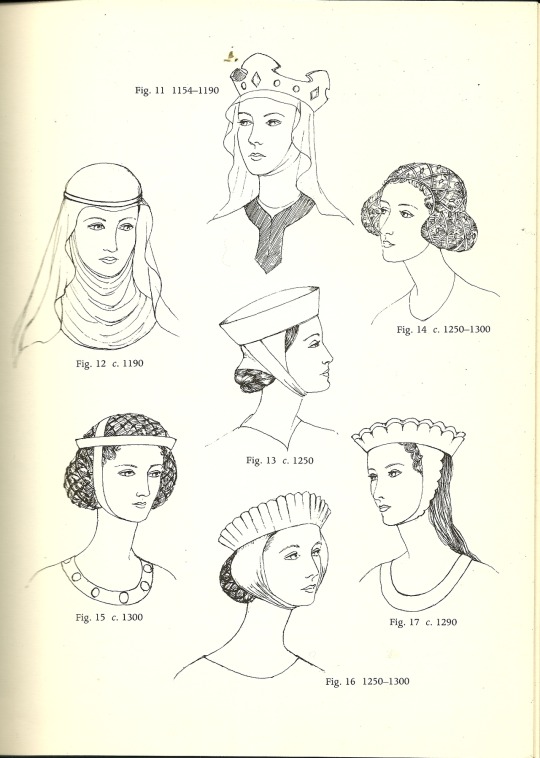

Medieval headdresses

1. Anglo-Saxon (600 – 1154) Simple Veils, Head-tires, Combs, and Pin

2. Norman (1066-1154) Couvre-chef, hair uncovered, and extreme length

3. Plantagenet (1154-1399) Wimple, Barbette, Fillet and Crespine

4. Plantagenet (14th century) Horizontal Braiding, Gorget

5. Plantagenet Crespine ( 1364-Late 14th century)

6. Horned headdress and escoffion

7. Lancaster (1430-1460) Heart-shaped and Turban Headdresses

8. Lancaster and York ( 1425-1480) Barbe, Loose Hair

9. York (1460-1485) Hennins and butterly hennins

Edit: So I definitely meant to delete the shorter version of this post that posted earlier today. Sorry. lol

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

“...A lone woman could, if she spun in almost every spare minute of her day, on her own keep a small family clothed in minimum comfort (and we know they did that). Adding a second spinner – even if they were less efficient (like a young girl just learning the craft or an older woman who has lost some dexterity in her hands) could push the household further into the ‘comfort’ margin, and we have to imagine that most of that added textile production would be consumed by the family (because people like having nice clothes!).

At the same time, that rate of production is high enough that a household which found itself bereft of (male) farmers (for instance due to a draft or military mortality) might well be able to patch the temporary hole in the family finances by dropping its textile consumption down to that minimum and selling or trading away the excess, for which there seems to have always been demand. ...Consequently, the line between women spinning for their own household and women spinning for the market often must have been merely a function of the financial situation of the family and the balance of clothing requirements to spinners in the household unit (much the same way agricultural surplus functioned).

Moreover, spinning absolutely dominates production time (again, around 85% of all of the labor-time, a ratio that the spinning wheel and the horizontal loom together don’t really change). This is actually quite handy, in a way, as we’ll see, because spinning (at least with a distaff) could be a mobile activity; a spinner could carry their spindle and distaff with them and set up almost anywhere, making use of small scraps of time here or there.

On the flip side, the labor demands here are high enough prior to the advent of better spinning and weaving technology in the Late Middle Ages (read: the spinning wheel, which is the truly revolutionary labor-saving device here) that most women would be spinning functionally all of the time, a constant background activity begun and carried out whenever they weren’t required to be actively moving around in order to fulfill a very real subsistence need for clothing in climates that humans are not particularly well adapted to naturally. The work of the spinner was every bit as important for maintaining the household as the work of the farmer and frankly students of history ought to see the two jobs as necessary and equal mirrors of each other.

At the same time, just as all farmers were not free, so all spinners were not free. It is abundantly clear that among the many tasks assigned to enslaved women within ancient households. Xenophon lists training the enslaved women of the household in wool-working as one of the duties of a good wife (Xen. Oik. 7.41). ...Columella also emphasizes that the vilica ought to be continually rotating between the spinners, weavers, cooks, cowsheds, pens and sickrooms, making use of the mobility that the distaff offered while her enslaved husband was out in the fields supervising the agricultural labor (of course, as with the bit of Xenophon above, the same sort of behavior would have been expected of the free wife as mistress of her own household).

...Consequently spinning and weaving were tasks that might be shared between both relatively elite women and far poorer and even enslaved women, though we should be sure not to take this too far. Doubtless it was a rather more pleasant experience to be the wealthy woman supervising enslaved or hired hands working wool in a large household than it was to be one of those enslaved women, or the wife of a very poor farmer desperately spinning to keep the farm afloat and the family fed. The poor woman spinner – who spins because she lacks a male wage-earner to support her – is a fixture of late medieval and early modern European society and (as J.S. Lee’s wage data makes clear; spinners were not paid well) must have also had quite a rough time of things.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of household textile production in the shaping of pre-modern gender roles. It infiltrates our language even today; a matrilineal line in a family is sometimes called a ‘distaff line,’ the female half of a male-female gendered pair is sometimes the ‘distaff counterpart’ for the same reason. Women who do not marry are sometimes still called ‘spinsters’ on the assumption that an unmarried woman would have to support herself by spinning and selling yarn (I’m not endorsing these usages, merely noting they exist).

E.W. Barber (Women’s Work, 29-41) suggests that this division of labor, which holds across a wide variety of societies was a product of the demands of the one necessarily gendered task in pre-modern societies: child-rearing. Barber notes that tasks compatible with the demands of keeping track of small children are those which do not require total attention (at least when full proficiency is reached; spinning is not exactly an easy task, but a skilled spinner can very easily spin while watching someone else and talking to a third person), can easily be interrupted, is not dangerous, can be easily moved, but do not require travel far from home; as Barber is quick to note, producing textiles (and spinning in particular) fill all of these requirements perfectly and that “the only other occupation that fits the criteria even half so well is that of preparing the daily food” which of course was also a female-gendered activity in most ancient societies. Barber thus essentially argues that it was the close coincidence of the demands of textile-production and child-rearing which led to the dominant paradigm where this work was ‘women’s work’ as per her title.

(There is some irony that while the men of patriarchal societies of antiquity – which is to say effectively all of the societies of antiquity – tended to see the gendered division of labor as a consequence of male superiority, it is in fact male incapability, particularly the male inability to nurse an infant, which structured the gendered division of labor in pre-modern societies, until the steady march of technology rendered the division itself obsolete. Also, and Barber points this out, citing Judith Brown, we should see this is a question about ability rather than reliance, just as some men did spin, weave and sew (again, often in a commercial capacity), so too did some women farm, gather or hunt. It is only the very rare and quite stupid person who will starve or freeze merely to adhere to gender roles and even then gender roles were often much more plastic in practice than stereotypes make them seem.)

Spinning became a central motif in many societies for ideal womanhood. Of course one foot of the fundament of Greek literature stands on the Odyssey, where Penelope’s defining act of arete is the clever weaving and unweaving of a burial shroud to deceive the suitors, but examples do not stop there. Lucretia, one of the key figures in the Roman legends concerning the foundation of the Republic, is marked out as outstanding among women because, when a group of aristocrats sneak home to try to settle a bet over who has the best wife, she is patiently spinning late into the night (with the enslaved women of her house working around her; often they get translated as ‘maids’ in a bit of bowdlerization. Any time you see ‘maids’ in the translation of a Greek or Roman text referring to household workers, it is usually quite safe to assume they are enslaved women) while the other women are out drinking (Liv. 1.57). This display of virtue causes the prince Sextus Tarquinius to form designs on Lucretia (which, being virtuous, she refuses), setting in motion the chain of crime and vengeance which will overthrow Rome’s monarchy. The purpose of Lucretia’s wool-working in the story is to establish her supreme virtue as the perfect aristocratic wife.

...For myself, I find that students can fairly readily understand the centrality of farming in everyday life in the pre-modern world, but are slower to grasp spinning and weaving (often tacitly assuming that women were effectively idle, or generically ‘homemaking’ in ways that precluded production). And students cannot be faulted for this – they generally aren’t confronted with this reality in classes or in popular culture. ...Even more than farming or blacksmithing, this is an economic and household activity that is rendered invisible in the popular imagination of the past, even as (as you can see from the artwork in this post) it was a dominant visual motif for representing the work of women for centuries.”

- Bret Devereaux, “Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part III: Spin Me Right Round…”

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Can you imagine what cathedrals would have been like if the medievals had access to neon lighting?

#bottled up divine essence#light itself was thought to be divine/from god himself which is part of the reasoning behind the large stained glass windows#when a medieval viewer looked upon precious materials and colorful light.. through their wonder at the material they reflect on#the wonder of god#stained glass#might make a real post on this soon

85K notes

·

View notes

Text

Illumination from a copy of Historia destructionis Troiae, dated from between 1325 and 1401.

463 notes

·

View notes