Text

Youth allege abuse at a Nova Scotia care centre

August 12, 2020 - At the Wood Street Centre in Truro, kids in the province’s care are physically restrained by staff — sometimes stripped of their clothes — and locked in solitary confinement for up to 12 hours at a time.

With no toilet in the room, kids are left with no option but to go to the bathroom on the floor. After they are let out, some have been told to clean it up.

Former residents describe their stays at the Wood Street Centre as horrific, traumatic, isolating and worse than juvenile prison.

Wood Street also formerly employed Matthew Rhodenizer, the youth worker charged in 2018 with the sexual exploitation of one of the kids he was supposed to be caring for. Rhodenizer, 30, is scheduled to stand trial in Truro Supreme Court over five days this fall, beginning October 19.

Residents of the Wood Street Centre are not locked up for committing crimes or for suffering from a mental health issue. They’re confined under the third circumstance in which one’s freedom can be taken away in Nova Scotia — being children in the care of the province’s Department of Community Services or Mi'kmaw Family and Children's Services, and deemed to have an emotional or behavioural disorder that requires confinement.

No formal medical diagnosis is required.

“I consider Wood Street torture,” one former resident tells me.

Another remembers the time he was dragged down the hall by his hair. Grabbed by his afro and locked inside a so-called therapeutic quiet room — a much nicer name for the old secure isolation rooms — because he didn’t complete make-up work for the centre’s in-house school, he says.

“I screamed until my fucking throat was bleeding,” he tells me.

“How is it therapeutic if people are smashing themselves and frigging getting suicidal from being in there?”

Physical restraints and isolation are permitted by the province’s Children and Family Services Act as last resort measures, after other interventions have been exhausted. But former residents and staff say the practices are eagerly overused by some staff.

In cases where children use their clothes for self-harm, the centre’s clinical director will order staff to remove their clothing, and provide an alternative piece of clothing, says Department of Community Services spokesperson Shannon Kerr.

However, former residents say children are sometimes left naked in isolation, while being filmed on a security camera.

Former residents say they are kept isolated in their rooms for speaking to each other without a staff member present, an infraction known as a “private conversation”. If residents leave their rooms without asking — even to go to the bathroom — they could be locked up in isolation or kept in their rooms for up to a week, a former resident says. Your stay can be renewed for something as simple as having a private conversation, talking back to staff or skipping ‘school’.

Not incidentally, one former resident says she was told her education at Wood Street would count toward her high school credits. But that’s not the case, as she later discovered.

Although Kerr says that teachers are licensed through the province and follow the curriculum, she didn’t say why school credits from Wood Street don’t count.

The provincial ombudsman’s office says it received 331 complaints from residents over three years, predominantly reporting issues with staff, policy and education. 15 of those complaints were related to being restrained and solitary confinement.

Over roughly the same time period, 379 children went through the facility.

The ombudsman's office doesn’t make the nature or outcome of those complaints public.

Without independent oversight from a child and youth advocate in Nova Scotia, children in the system who face violence or ill-treatment inside institutions are left with little recourse, experts say.

Since the facility opened in 2003, 1,592 children have been locked inside.

There are currently 1,016 children in the care of the province.

--

A 2007 N.S. Court of Appeals decision hones in one of the more controversial parts of the legislation. How precisely does “troubling behaviour” — with evidence of truancy and staying out late at night — translate into an “emotional or behavioural disorder” that requires a secure treatment order for Wood Street?

In this particular case, the judges found the evidence didn’t support the order. But as a practical matter, by the time an appeal can be heard, kids will likely have already spent significant time in the facility. That fact renders the process relatively moot and rarely practiced, says a lawyer who has represented many kids in the same boat.

Speaking on condition of anonymity – the DOJ isn’t a big fan of N.S. Legal Aid lawyers criticizing their work, as it turns out – he tells me that the legislation is both too broad and too narrow.

“Too narrow in that it offers a service that supposedly is valuable but it's only available to youth in care,” he says.

“Either it’s a good thing that’s being denied to the majority of youth or it’s a bad thing that’s being imposed on a minority.”

In either case, in his view from the trenches, he says the legislation is unfair.

“The grounds for being admitted into Wood Street are just so vague and the legal test, so permissive, that I just don’t think it’s really practical to be able to resist it,” he tells me.

With issues like truancy, broken curfews and refusals to take medication presented in court as evidence of behavioural disorders, one former resident argues that kids are being thrown in there for “stuff that normal teenagers do”.

“They don’t help kids, they just throw you in and hope for the best,” she said. “Kids will do anything to get out of that place.”

The physical process of travelling there can be pretty awful too.

In a 2016 Family Court decision, Chief Justice Lawrence O’Neil wrote that detained children are transported between courts and Wood Street in “draconian ways” — handcuffed and imprisoned at police facilities.

O’Neil said the court heard “disturbing evidence” of the conditions a child with autism was subjected to while being taken into the province’s custody.

“Transporting a vulnerable child as if he is a violent adult offender, is a serious issue that should be addressed,” wrote O’Neil.

The “apparent acceptance” of this protocol forced O’Neil to question who oversees the decisions and quality care provided by the minister charged with the care of children, he wrote.

“Perhaps it is time for a child’s advocate, independent of the government authorities, to be charged with responsibility to advocate for children in care,” wrote O’Neil.

O’Neil is not alone in his concern over a lack of a child and youth advocate in Nova Scotia. The province is one of only two jurisdictions in Canada without the office that can provide independent oversight and authority over the ministry, with the power to investigate ill-treatment of children in the child welfare system.

In 2018, Ontario’s PC Doug Ford government cut the watchdog position to the dismay of child advocates.

Without a watchdog, who could publicly report issues, children in the province are left without a voice on the programming and policies that impact them says Alec Stratford, the executive director of the Nova Scotia College of Social Workers.

The ombudsman’s office doesn’t have the mandate to do systemic and policy advocacy, he says.

“Wood Street has become a place of last resort,” says Stratford.

“That’s not appropriate.”

“It’s meant to be a treatment centre. I’ve had folks describe it more of a prison setting.

“Political parties, when they’re in opposition, love the idea of a child and youth advocate’s office, but when they get into power they certainly shy away from it. Because at the end of the day it’s oversight.

“This government in particular right now seems to have challenges with oversight,” says Stratford.

[email protected] -- Originally published on August 12, 2020

1 note

·

View note

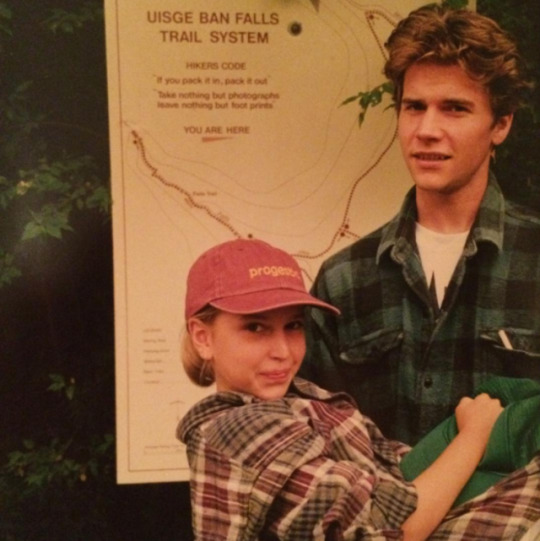

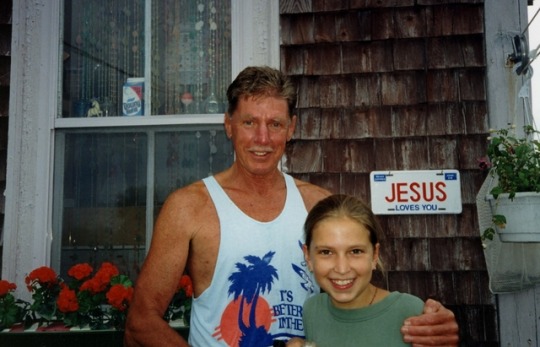

Photo

Garrett Mason, Halifax Magazine, 2018

0 notes

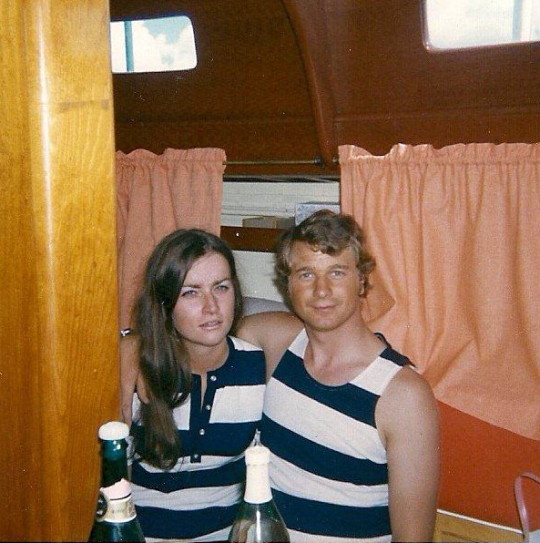

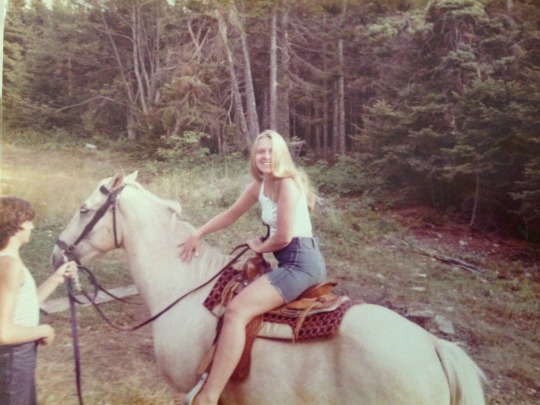

Photo

sightseeing

0 notes

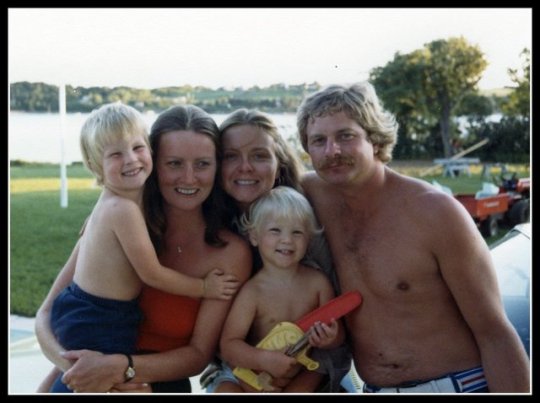

Photo

Bob Nagel. Always a pleasure.

0 notes

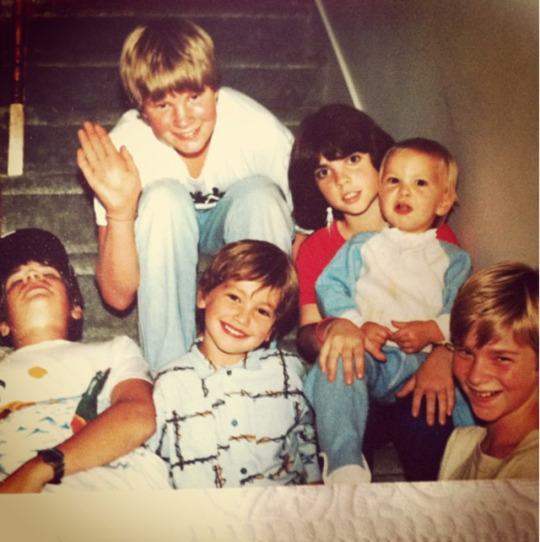

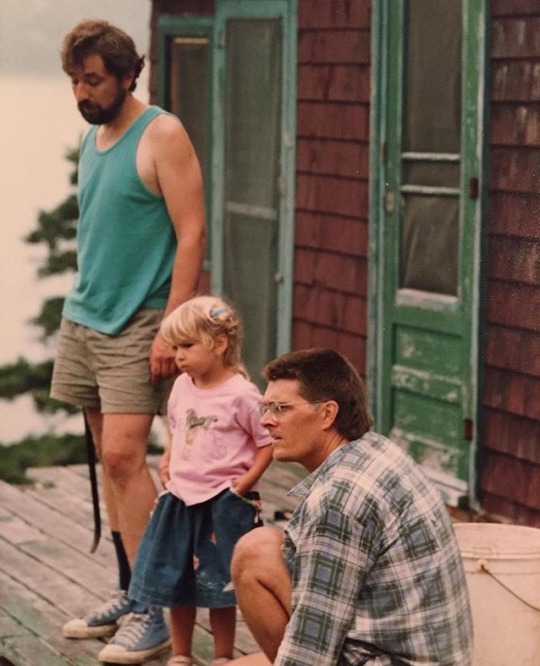

Photo

family portraits

#family#1970s#big bras d'or#cape breton#cape breton island#alan macleod#kathleen macleod#jon prentiss#bedford#nova scotia#new york#hatti prentiss

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Martinique Beach, NS

0 notes

Photo

Crystal Crescent Beach, NS

0 notes