#1.2.3

Text

Les Mis 1.2.3

I think Pilf or someone already mentioned it this time around, but Hapgood’s use of thou here is to represent the familiar second person pronoun tu. Valjean is expecting to be addressed with this familiar form: he’s as surprised to receive the respect of Monsieur (Sir) and vous (you) as he is to not be kicked out.

This grammatical issue will show up throughout the novel to signal how characters relate to each other (and which they/Hugo will comment on), so it’s something the translators need to account for. But since English dropped thou/thee/thy/thine, there isn’t a comparable way to signal this formal/familiar divide that doesn’t sound old-fashioned and odd.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Jean Valjean, discharged convict, native of’—that is nothing to you—‘has been nineteen years in the galleys:...'

I still love the energy of the narrator deciding we just straight up don't need to know certain info. Like, is it a town that doesn't exist anymore? Is it somewhere we would recognize but not important to the story? Is it a symbol that where valjean comes from no longer has any bearing on his future?

#les mis letters#the narrator going hmmmm i will not tell you instead of just omitting that part of the sentence lives in my head rent free#1.2.3

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Everytime [the Bishop] said this word ‘monsieur,’ with his gently solemn and heartily hospitable voice, the man’s face lit up. Monsieur to a convict is a glass of water to a man dying of thirst at sea.”

Today’s chapter just broke my heart. Valjean’s disbelief that anyone should treat him with kindness and dignity is almost too much to bear - even if he later robs them, doesn’t truly yet believe such kindness is anything but foolishness.

Just, that he’s completely given up hope to the point he immediately tells them everything about his past, then insists on repeating it as if he doesn’t quite believe they heard him. His ramblings about his life, the way he finally seems to be able to talk and unburden himself of all the horrors that have happened to him.

“Oh, the red tunic, the ball and chain, the plank to sleep on, the heat, the cold, the work gang, back to the prison ship every night, the lash, the double chain for nothing, solitary confinement for one word - even when sick in bed, the chain. The dogs, a dog is happier! Nineteen years! And I am forty-six, and now a yellow passport, just that!”

It just makes you want to cry.

#it’s also heartbreaking that conditions in prison nowadays are similarly horrific but I digress#les miserables#les mis letters#1.2.3#jean valjean#bern speaks

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 1 Stage 2 Poll 3

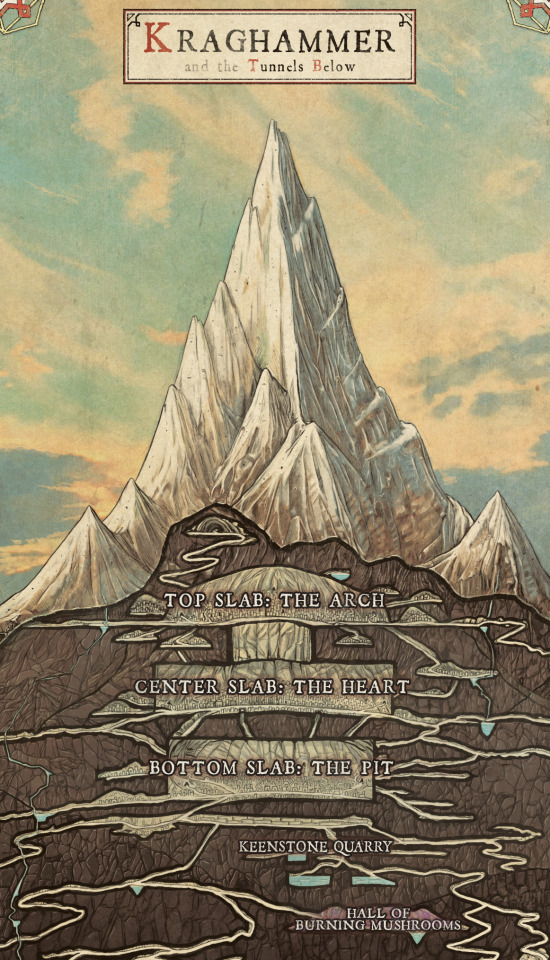

Kraghammer, Tal'Dorei: Kraghammer is a dwarven city in the Republic of Tal'Dorei. It was a short stop on Vox Machina's journey to the Underdark, but it is where the first streams of Campaign 1 began.

image by andy law from tal'dorei campaign setting reborn

Jigow, Wildemount: Jigow is a Kryn Dynasty city in northern Xhorhas. It has only been mentioned in passing onstream, but it is a key location in Call of the Netherdeep.

image is official art by max dunbar from call of the netherdeep

#exandria#kraghammer#jigow#tal'dorei#wildemount#taldorei#critical role#poll post#notpollprop#exandria city showdown#round 1#1.2.3

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean Valjean’s horrible awful relationship with religion is really fascinating— the way religion becomes deeply meaningful to his life but is also still a tool of social control that is used to violently oppress him. I love this line where he describes how bishops would “preach” to him in the galleys:

“[the bishop] said mass in the middle of the galleys, on an altar. He had a pointed thing, made of gold, on his head; it glittered in the bright light of midday. We were all ranged in lines on the three sides, with cannons with lighted matches facing us. We could not see very well. He spoke; but he was too far off, and we did not hear. That is what a bishop is like.”

Jean Valjean’s early relationship with religion is as this horrible violent obligation. He attends “mass” in the galleys, where cannons are pointed at him, so that if anyone in the crowd acts up they can all be massacred. The bishop is also so impossibly distant that they can’t even hear him. No one in prison is trying to actually speak to Jean Valjean or the other convicts; they’re just violently forcing them to act out the empty forms of Christianity while not allowing them to truly participate in it.

And while Myriel does change his life, and his faith…. Jean Valjean never fully internalizes the way Myriel treated him as an equal and insisted that they were brothers. And that’s in large part because of the hostility or terror which which the rest of the Church and society views him.

We’re told later that in the convent, Jean Valjean prays to the nuns doing penance, because “he did not dare to pray directly to God.”

There’s a fascinating tension between the fact that religion is extremely important to Jean Valjean’s life, but also, that same religion is often used against him as a tool of violent social control. He belongs to a religion that rejects him violently. He prays to a God that he does not dare to pray to directly, out of self-loathing. It’s a really strange complex relationship.

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I started rereading les mis, in french this time, and I'm sort of catching up to les mis letters (only sort of, for now, since I'm still at chapter 1.2.5 I think) and I do wanna talk about the title of the book because that title has fascinated me ever since I opened that book 14 years ago in its greek translation. So the greek translation of the title "les Misérables" mystified me. I think a big part of western languages have a variation of the word "misérable" in their vocabulary so the translation of the title is pretty much consistent (obviously not every western language, idk what happens with scandinavian translations or hungarian or russian for example). In greek we do not have the word "miserable" or "misery", we kind of use the word "mizeria" but only as a "western" variation of the greek word we have for misery, so we don't have the equivalent adjective. So the original greek translator needed to find a brand new adjective, in greek, to convey the meaning of the title, and honestly, what a task that is, finding the greek equivalent of probably the most iconic title in literature ever, just one word to encapsulate 1500 pages of text.

The word finally used is "Άθλιοι" (Athlioi) the plural form of "Athlios". It's an ancient greek word that is also commonly used in modern greek as is the case for a huge part of our vocabulary. So the ancient greek definition of "Athlioi" is "struggling, unhappy, wretched, miserable". In modern greek, the definition is more or less the same: "seedy, miserable, poor, terrible", except for the last word "terrible" that has an interesting connotation. The definition of "Athlioi" as terrible is an addition of modern greek. "Terrible" by itself maybe doesn't say much and it seems as a mere variation of the classic definition of Athlioi as "miserable, poor, wretched" etc. But from miserable and wretched to terrible there is an interesting leap. While "seedy, miserable, poor, terrible" are the english translations of the greek word "Athlioi" that I find on wordreference.com, I get very interesting results when I inverse the search, this time searching for the greek translation of the following english words (on wordreference or glosbe): despicable, nasty, vile, shady, appaling, loathsome, wicked, infamous, monstrous, horrible, lame, shabby, mangy, mean, vicious. You may have guessed it, all of the above are translated into "Athlios" in greek (among other words). The reason for that is that "Athlios" in modern greek has an extremely negative connotation. An "athlios" is not just a miserable wretched poor outcast. An "athlios" is a despicable human being, one that inspires disgust, one you should avoid in any case. A horrendous, vile, monstrous, hateful, creature. I am not sure if the word "Athlios" already had that definition at the time of the first greek translation (end of 19th century) but my bet is that it did, because that is what the word is primarily used for in Greece ever since I remember myself. When we use the word "Athlios" in greek now we rarely if ever talk about someone "miserable", "poor" or "wretched". We normally talk about someone or something despicable. If it's a person, 99% of the time this has a purely moral connotation aka, someone who is morally despicable. They could be a poor person, (a Thenardier type of vile individual) or they could be rich, doesn't matter really.

I am not sure if the word "misérable" or the english word "miserable" have this connotation. It is one thing to be wretched and totally another thing to be despicable and loathsome. Is this very close to the french word "misérable"? "Misérable" in french primarily means "pitiful, wretched", with one mention of "despicable", it is true. In Larousse however (the classic french dictionary) I cannot find one definition of "misérable" with the "vile, despicable" connotation that the word "Athlios" has. I am sure "misérable" can be used that way, and it can be translated that way in english, but vile and despicable are not the leading definition one thinks about when they encounter the word. When we use the word "misérable"/miserable, we normally do not immediately think of a despicable, vile, loathsome individual. So this choice of title by the greek translator takes some liberties. He could have used our greek word for "pitiful", "outcast" or one particular greek word we have for "scorned" that has a particular depth because it means scorned, neglected and forgotten by society all at the same time. Or he could have went for our word for "miserable" in the sense of "unhappy". All of these could have worked well enough. But he went for "Athlioi". Why? Athlioi is the only word that has a truly negative connotation for the morality of a person, of their moral value, and the way society percieves that moral value.

I got to the chapter "The Evening of a Day of Walking" where Valjean makes his first appearence. The english translation is this:

"It was difficult to encounter a wayfarer of more wretched appearance".

Then Hugo proceeds with a description of his appearance that is particularly unsettling, to say the least. He was literally dressed in rags with iron-shod shoes and he had holes in his clothes. At the end of the description he says:

"The sweat, the heat, the journey on foot, the dust, added I know not what sordid quality to this dilapidated whole".

So that guy is 1) certainly unhappy, 2) clearly wretched, 3) has a sordid quality and 4) a dilapidated look.

It is interesting that in french, the phrase "wretched appearance" is actually "aspect misérable". It is important to note this because this is the first time that the author gives us a description of a character that encapsulates what a "Misérable" according to the title actually is. Moving along, Valjean is not accepted in any inn or house and the people force him to leave because they are horrified by 1) his appearance and mainly 2) his profile as an ex convict that makes him a "Dangerous Man". "Dangerous Man" is literally written on his passport. A pitiful creature is maybe not that loathsome by itself, but a "Dangerous Man" is definitely something that you want to stay away from.

At the chapter "The Heroism of Passive Obedience" (1.2.3) Valjean enters the bishop's house and the bishop's sister sees him and describes him like this:

"He was hideous. It was a sinister apparition."

"Mademoiselle Baptistine turned round, beheld the man entering, and half started up in terror".

"Wretched" and "pitiful" cannot cover the impact this individual had on people, on society. That man was not just deeply unhappy, in a deplorable state, wretched and pitiful. That man was appaling. That man was loathsome. That man inspired horror, disgust, and intense, bone deep hatred. It is important to note this aspect of "misérable". The fear society has for the injustice it creates is so strong that it is far easier to dehumanize these individuals by slapping the label of "despicable", "vile", "loathsome" on them. It makes their total marginalisation easier because it justifies it. People are truly disgusted by and terrorised by Valjean. For society, there is a reason why that man is in a pathetic, deplorable, "miserable" state. It's because he is truly, irrevocably, morally hideous, loathsome and nasty. He is "dangerous". He truly is a monster inside out. And that particular manifestation of social misery is nicely conveyed by the word "Athlios" in my opinion.

#les miserables#aspa reads les mis#jean valjean#les mis letters#catching up#les mis translations#lm 1.2.3#lm 1.2.1#les misérables#aspa rambles#long post#the brick

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey, les mis tumblr, can you help me out? i'm a little behind on les mis letters so im reading 1.2.3 right now, and i was wondering how much one hundred and nine francs and fifteen sous would be in USD, and approximately like. how much it is in general terms of, what it would've gotten you at the time and the equivalent today?

i imagine it's not very much at all, but i am interested to know the specific details of it.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

「支え」

光陰矢の如し、束の間の休息、束の間の拘束、束の間の気配り、束の間の支えの中にも、蔓延る人間性。

時が過ぎれども、記憶は束の間残る。

あっと、その間に、誘惑に負けるのさ。

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

And olsun səhərə! And olsun sakitləşməkdə olan gecəyə! Rəbbin səni nə tərk etdi, nə də sənə darıldı.🌙

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

This chapter is both heartwarming and heart-wrenching. It portrays the first instance of a life-changing act of kindness (the second one is that of Marius towards Éponine, and the third one is that of Jean Valjean towards Javert).

Valjean’s anger and honesty at the moment he enters the house is heart-breaking. By that point, he is desperate and humiliated. Having just learned that lies can serve him better than the truth (a wisdom he will utilize time and again in the future), he still chooses to be rudely sincere. This is similar to what he will do at the end, revealing the truth about himself to Marius. In both cases, he chooses not to disclose mitigating circumstances. Why is he like this?

It’s touching how Valjean is surprised and moved by every detail of the bishop’s attitude toward him. "You are letting me in?! You are addressing me 'vous'?! You let me sleep in a bed?! You are not asking for money?!"

Valjean’s description of his experience at the galleys brings me to tears: “Oh, the red coat, the ball on the ankle, a plank to sleep on, heat, cold, toil, the convicts, the thrashings, the double chain for nothing, the cell for one word; even sick and in bed, still the chain! Dogs, dogs are happier! Nineteen years! I am forty-six. Now there is the yellow passport. That is what it is like.”

Each time I read about Bishop Myriel asking Mme Magloire to put a silver set on the table, I think that it seems he is doing this to seduce Valjean. Of course, this is out of his character, and he most probably wanted to show his respect and welcome to the guest. Still, it is a very bothering act.

And, of course, it was important for Hugo to provide the contrast between Bishop Myriel and some random bishop seen by Valjean during his imprisonment. He doesn’t even know that his host is not just a priest but a bishop, yet he still recalls his encounter with a distant and glittering prince of the Church. “That is what a bishop is like,” concludes he.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

#my posts#les mis#les miserables#victor hugo#lascelles wraxall#wraxall translation#lynd ward#lm 1.2.3#jean valjean

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

LES MIS LETTERS IN ADAPTATION - The Heroism of Passive Obedience, LM 1.2.3 (Les Miserables 1934)

The door opened.

It opened wide with a rapid movement, as though some one had given it an energetic and resolute push.

A man entered.

We already know the man. It was the wayfarer whom we have seen wandering about in search of shelter.

He entered, advanced a step, and halted, leaving the door open behind him. He had his knapsack on his shoulders, his cudgel in his hand, a rough, audacious, weary, and violent expression in his eyes. The fire on the hearth lighted him up. He was hideous. It was a sinister apparition.

#Les Mis#Les Miserables#Les Mis Letters#Les Mis Letters in Adaptation#Les Mis 1934#Les Miserables 1934#Jean Valjean#Valjean#Harry Baur#pureanonedits#lesmisedit#lesmiserablesedit#lesmis1934edit#lesmiserables1934edit#T_T#;w;#LM 1.2.3#Truly Baur is one of if not the most Unbearably Sad Beast Valjeans.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yoshitomo Nara: ‘1.2.3…’ (2006)

360 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hate the premise of this chapter so much (”the heroism of passive obedience” just brings back all of my issues with how Mlle Baptistine and Mme Magloire are treated), but if the title were different so that I could know that wasn’t what Hugo wanted to focus on, it would be so much better, because most of it really consists of heartbreaking moments between Valjean and the bishop.

Valjean is upfront about his identity after entering, but he doesn’t believe that he’s not being cast out. In response to the bishop, he sort of rambles? For instance, he repeats his origins three times in a row (”’I am a galley-slave; a convict. I come from the galleys’”) even before he pulls out his yellow passport to confirm it. His speech is similarly repetitive when he talks about learning to read and asks if he will be provided with shelter, highlighting the extent of his shock. It’s also clear how low his standards for treatment are - not just because he can’t process that someone is actually giving him a place to stay, but because he automatically asks if there’s a stable at the end, assuming that if he is given shelter, it could only be around animals, not people. He laments that he is treated worse than a dog (”’dogs are happier’”), but he’s also internalized the idea that he is equal to or below most animals.

Also, these lines are incredible:

““What need have I to know your name? Besides, before you told me you had one which I knew.”

The man opened his eyes in astonishment.

“Really? You knew what I was called?”

“Yes,” replied the Bishop, “you are called my brother.””

Watching Valjean get so much joy out of basic respect (being addressed as “sir” and with what I assume is “vous”? The translation of “tu” to “thou” in English in confusing, since we don’t use that anymore, but it seems to be what would make sense context-wise) is both sweet and desperately sad, but this? This is one of the most moving moments so far. The way Valjean jumps to astonishment (the connotation is unclear, but I’d assume he either assumes he’s notorious or that the bishop is simply full of knowledge) and the bishop flips their relationship from a hierarchical one (convict-bishop) to an equal one! With a word! And if Valjean isn’t used to the basic respect that would be given to almost anyone, then what must being treated as an equal - as a “brother” - feel like?

#les mis letters#lm 1.2.3#jean valjean#bishop myriel#I have so many feelings about this chapter#I'm still processing

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

jvj ur such a bby ily

10 notes

·

View notes