#Fierce Care Ateneo

Text

UT Califas fierce care ateneo, 5-27-17, 2.00-5.00 p.m.

Compañerxs,

The Universidad de la Tierra Califas' Fierce Care Ateneo will gather on Saturday, May 27, from 2.00 - 5.00 p.m. at Miss Ollie's / Swans Market (901 Washington Street, Oakland, a few blocks from the 12th Street BART station) to continue our regular, open reflection and action space to explore questions and struggles related to the emerging politics of fierce care as well as some of the questions below.

Over the last few months we have been confronted by the exciting opportunity of engaging the CNI-Zapatista proposal of collectively advancing Mexico's several experiments in radical democracy. Specifically, the Zapatistas along with the Congreso Nacional Indígena (CNI) have announced a political strategy to organize from below and the left. Practically it means village by village communities will convene in permanent assembly and gather to re-imagine the current political system. Part of the strategy will be to expose the spectacle by organizing a political force that will be able to put forward a presidential candidate, an Indigenous woman. Here it is important to note, the joint Zapatista and CNI initiative states that the effort will not involve itself in the "official" electoral system attached to the political parties, either as one of many that only pretend to be an opposition. Rather, the strategy is to be outside the official system, yet engage a serious candidate. The proposal is clearly a creative, politically imaginative moment of torreando with the formal political apparatus —the electoral circus that ostensibly democratic institutions manage. It is also a profound moment of mobilization from below in the form of the CNI-Zapatista consejo that selects the candidate but also, and maybe more importantly, the call for a permanent assembly across the nation, a truly impressive level of organizing from below and to the left.

As México profundo mobilizes, México imaginario spills over with violence. On May 10 of this year while thousands of mothers were in the streets across Mexico to make visible and contest the disappearances and murders of their children on Mother’s Day, Miriam Rodriguez was assassinated in her San Fernando, Tamaulipas home. Rodriguez was the director of Comunidad Ciudadana en Búsqueda de Desaparecidos en Tamaulipas, a non-profit she helped establish that currently includes some six hundred families who search for a disappeared child as a result of violence linked to the war on drugs. Rodriguez is joined by Javier Valdez, yet another of Mexico's prominent journalists who has been assassinated for their courageous efforts to confront impunity. Valdez is part of a growing list of journalists, including Sonia Córdova, who while attacked and survived witnessed the death of her son. Mexico has become a nation notable for being one of the most dangerous places on earth for journalists to do their work. Many have pointed out that this is yet another moment of impunity in the over decade long intensification of the war on drugs begun under President Felipe Calderon and continued through the present with President Enrique Pena Nieto, who it is reported responded to the week's tragedy by tweeting with Leonardo DiCarpio. The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) reports that in this year alone Mexico suffered 23,000 dead ranking alongside Syria in the amount of death attributable to war. Over the ten years of the expanded drug war the IISS estimates 200,000 dead, in reality no one has an exact number. What explains this level of death? Impunity?

In Berkeley in late April several collectives and family justice struggles from across the Bay Area and beyond gathered for an encuentro to share from several sections of an ongoing people's investigations into the wrongful killing of Asa Sullivan by the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) on June 6, 2006. SFPD officers killed Asa when they illegally entered his residence and shot him seventeen times. Despite an eight year battle to bring the case to trial as a civil suit, in the fall of 2014, a jury determined that the police had not acted with excessive force. Sanctioning the police's entrance into the residence without a warrant the jury validated the police defense of "suicide by cop." Asa's life —the legal team and their experts representing the police argued— was one that even he did not want.

In response, a cluster of groups along with the family at the center committed to a people's investigation. People’s investigations are community-based, grassroots responses to state and state-manufactured violence that place the family and practices of fierce care at the center of the investigative process. Against the onslaught of this violence, people's investigations serve as "institutions of the commons," tools for community regeneration, and spaces of assembly where new possibilities for justice, accountability, and safety are imagined and practiced collectively in, against, and beyond the racial capitalist state. In the case of Asa and his family, the collective, community-based convivial research marks a refusal to abandon the family after the loss of the trial, and a refusal to accept a justice defined by the state.

The encuentro emerged from this collective investigation and was convened by a number of groups across the Bay: Justice for Asa Sullivan; Center for Convivial Research and Autonomy (CCRA); UC Berkeley Law Policy Advocacy Clinic (Police Accountability Project); Acción Zapatista; Universidad de la Tierra Califas; Idriss Stelley Foundation and Poor Magazine, and included families and justice struggles from Stockton, Hayward, and San Francisco, including the families of James Rivera Jr., Colby Friday, James “Nate” Greer, and members of the Justice for Alex Nieto coalition, as well as community lawyers and comrades. A point of focus was the legal genealogy of “suicide by cop,” a state category to sanction militarized police violence and allocate disposability to historically marginalized communities.

In the current expanding settler-colonial present, increasing numbers of lives are marked as "illegible" or "disposable," a sometimes double condition made possible by intertwined technologies and an array of contingent forces that include the juridical apparatus and a concatenation of institutions, laws, and statements in the present "democratic" state. The production of illegibility happens when the juridical apparatus mobilizes a set of "selective stereotypes" through which it places certain subjects within a culturally devalued frameworks of legibility (see Leti Volpp, "Framing Cultural Difference. Immigrant Women and Discourses of Tradition"). Cultural illegibility does not only inflect and justify court decisions; it also strategically produces subjects marked for abandonment or death. Contingent forces can also include funding sources, various projects, and shared attitudes that play out idiosyncratically in specific violent actions, sometimes authorized and other times not. This occurs in the context of increasing militarized violence, including heightened violence at national borders along with persecution of migrants and immigrant populations increasingly in the interior. Although not on the level of Mexico, the level of senseless violence aimed at Black and Brown communities in the U.S. continues unabated. Such an interrogation exposes strategies of “disposability” and erasure aimed at particular communities. At San Francisco State, which declared itself a Sanctuary Space, struggles led by students expose such production of illegible and disposable life, as they denounce the university’s recent failure to protect Palestinian students, especially women, from the violent threats and attacks on campus, in a context of officially authorized islamophobia (see Diana Block, "No Sanctuary for Palestinian Scholarship").Organized resistance to this local failure in the distribution of "security" and care makes clear that 1) institutional protection in its current neo-liberal and/or nationalist forms is at best unreliable and at worse destructive; 2) such institutions are complicit with the crucial site of the racializing production of profit, namely the nexus between Western States and (Zionist) settler-colonialism.

Meanwhile, Mothers' Day in Califas was celebrated with related gatherings contesting violence and attempts at erasure. National Black Mamas Bail Out Day an effort initiated by Southerners On New Ground (S.O.N.G.) and coordinated by Law 4 Black Lives and other groups in the "movement for Black Lives cosmos" focused on raising bail money to release Black mothers from jail and organizing actions across multiple states. Declared in solidarity with all oppressed peoples, including an ongoing solidarity with Palestine and the right to return, the S.O.N.G. initiated action draws attention to two critical moments: a system of racialized segregation; and the ongoing attack waged by capital and state forces that is continuously disrupting the social fabric of Black and Brown communities. At the same time, also in recognition and celebration of Mothers' Day, mothers and family members gathered in Stockton where on the steps of City Hall, they assembled in a circle for several hours, sharing strategies for exposing and responding to police violence and ongoing contexts of impunity that include the District Attorney, the City Manager, the various and overlapping law enforcement agencies and task forces, within the context of the constant reproduction of state-manufactured violence. Many of these conversations continued over food, singing and dancing well into the afternoon in the park across from City Hall.

From these spaces and efforts with families at the center, compelling counter-narratives emerge. New relations for battles and survival are forged. As spaces of assembly and learning, these spaces and actions hold a potent energy not limited by or even legible through the category of “social movement.” Taken collectively, they expose the spectacle of the political system. How are we expected to put our faith in any of the solutions put before us to stop the violence? Police sensitivity trainings, community policing programs, appointed oversight boards, or processes of accountability that hinge on the higher authority of the DA, the Justice Department, the United Nations—they are all organized through spectacle.

Similarly, from the detention centers of Washington state to Israeli prisons to the streets of Indian-occupied Kashmir, ongoing and profound resistances throughout April and May have exposed violence in the name of “national security.” Detainees targeted by ICE raids, many of them women, launched hunger strikes at the Northwest Detention Center (NWDC) (a private prison operated by the GEO group and contracted by ICE) and also at NORCOR, a county jail in rural Oregon. The demands of the NORCOR group were recently acknowledged after nearly a week without eating. The efforts of both groups revealed not only the conditions of detention, but the strategies: people are removed from their communities and isolated from their families and at the same time denied legal documents and recourse to court processes by the state that detained them. On April 17, an estimated 1200 - 1500 Palestinians held in Israeli prisons commenced a hunger strike that has now well passed the month mark, with more prisoners joining in waves (see “Hunger strike a 'race against time' group warns, as 60 prisoners join strike” ). Among the strategies that their demands expose: isolation from family; illegal detentions; as well as transfers between prisons and out of Palestine that seek to break connections and at the same time violate, and serve to reinscribe, illegal connections and claims to land. Putting their lives at high risk with clear demands, hunger-strikers highlight the strategic failures of both the legal system and the care provided through the prison-industrial complex. On the outside, mothers of those on strike have also stopped eating in a collective resistance across walls (see Maram Humaid, “Starving with their Sons”). At a recent event at Freedom Archives in San Francisco, Palestinian political cartoonist Mohammad Sabaaneh was joined by Aarab Barghouti, the youngest son of prominent political prisoner and hunger striker Marwan Barghouti, in an collective effort to circulate and build support for the hunger strike, including through the "salt water challenge," a campaign of global solidarity with the hunger strikers and with Palestine (see Gideon Levy, "Marwan Barghouti's Son: 'My Father is a Terrorist Just Like Nelson Mandela'"). Through drawings and testimony, they both spoke to the pervasiveness of occupation, a carceral state that is everywhere--crowding, containing, and restricting movement as well as relations. While in Kashmir, the decades long insurgency against Indian-occupation has also escalated in recent months including a recent protest against Indian occupying soldiers led primarily by young women, many of them college students (see Faisal Kahn, “Female Kashmiri students lead anti-India protests”). For some, the new insurgency is a response that takes its shape from a collective disavowal of the electoral process (see Kamil Asan, “Kashmir’s New Uprising”). These protests register outrage at violence and also a refusal to accept the solutions put forward by state processes of democracy: namely, the sham of electoral politics.

Can we read these as struggles for radical democracy, a desire for new forms of political organization? Can we re-imagine together a new political system on a world scale? And for our purposes, what is the relationship between emergent practices of radical democracy and fierce care? What happens if we locate and celebrate “fierce care” at the center of our struggles, refusing to let the category “slip” from its position within capital’s current conjuncture? Surely, it is not just about “caring more” or “caring better” but instead must involve an analysis of what capital has done and continues to do to our efforts to engage each other through care. If we are to take up the question of the endemic, manufactured violence across Greater Mexico which threatens to overtake us everywhere, care cannot be reduced to a “technology of the self” or a gauge for our “activism” (see Robert Kurz, "No Revolution Anywhere") but instead must operate with an analysis of the current conjuncture, and a collective reorientation. If we make this care central, does this shift how we connect our struggles with the mobilizations underway across Mexico through the shared efforts of the EZLN and CNI?

South and North Bay Crew

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Girl from Bauko

a short story by an Ilocano writer.

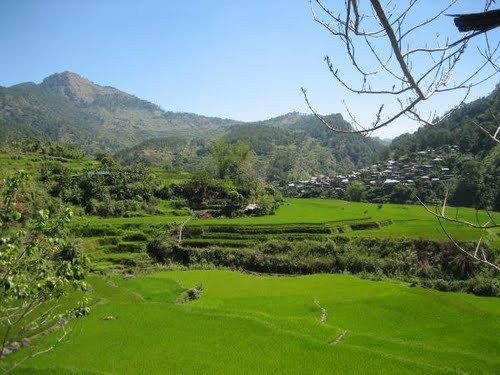

BAUKO IS a remote mountain town up in the wilds of the Cordilleras. It is some five thousand feet above sea level, and thick fog covers the towering mountain slopes every day, even in mid-summer, and the golden sun hardly be seen at high noon.

Of all stories - love stories - worth remembering my Father told me, not one can surpass the poignant story of a ravishing and winsome mountain lass by the name of Maila.

Maila was a Kankanay, one of the principal tribes of mountain Province. Indeed, Maila was a bundle of unsurpassed pulchitrude and vivacity, possessing a pair of bewitching dimples in her rosy checks, deep as the ravines surrounding her father's luxuriant mountain clearing up in Bauko.

The epic story of World War II would be incomplete and colorless without this beauteous mountain lass Maila, Father would tell me with a sparkle in his eyes, because Maila was everything to him during those dismal , difficult years of enemy occupation.

Father was a guerillero during the war. He was not a professional soldier, he repeatedly told me, since before the outbreak of the Pacific War he was still young, vibrant and innicent, and was bent on his studies at the U.P. in Padua Faura.

Those days were the golden days of the Commonwealth under the tutelage of the charismatic political leader, Manuel L. Quezon. Padre Faura then was quiet and shady with giant acacia trees, branching towards the sky on both shoulders of the street, affording cool shades for the boisterous groups of colegialas heading towards the big and spacious corridors of the State University and the Ateneo.

Father joined the army probably because of compulsion of maybe he was afraid of those slit-eyed Japanese soldiers. In the mid-thirties, the cream of the Filipino manhood was called to undergo compulsory five-and-a-half-mo the training in a care all over the islands; Father was among them, although he opted to take summer infantry training in Camp Murphy, the premier army camp I those days.

Prewar trainees and cadets of the ROTC units of Manila's colleges, were on the list of the Japanese Empire and sure death was the penalty for being one of them.

Why and how bphe came to Bauko, he did not tell me, but guerilla rose in those difficult years lived anywhere in the wilds of Northern Luzon.

Perhaps the dense mountain growths of the Cordillera ranges provided safe sanctuary for them. They were wanted by the Japanese forces for sure and once the were caught, they were herded like animals to a monkey house with grills and baked under the burning sun to be skinned alive or tortured to death by all kinds of painful methods as by bayonet thrusts, merciless clubbings and by water cure. Japanese soldiers were no better than barbarians in Marco Polo time.

"I had a co-guerillo by the name of Lacuasan," Father would recall. "This man Lacuasan was as my age and was a native of sturdy Kankanay stock. Most of the time he wore a g-string and was armed with a hatchet and a spear. He had a perfect physique, with bulging muscles throughout his whole anatomy -- easily he could have competed with Charles Atlas or Henry Liederman.

Lacuasan was a runner, a courrier, of the famed 66th Infantry, the guerrilla outfit composed of mountain tribes -- fierce-looking Kalingas and half-civilized Bontocs and Ifugaos, much-feared headhunters of the mountain provinces. Lacuasan was fast moving in spite of his size Climbing treacherous and slippery trails like a deer, he knew every bend and waterhole in the vast plateaus of Bauko.

The 66th Infantry was commanded by a greying American officer, Major Parker Calvert, a West Pointer, who refused to follow the surrender orders of General Wainwright following the fall of Corregidor.

It was Lakuasan who invited Father to his mountain clearing atop a lonely knoll in Bauko. The hut he owned was a small one, surrounded by a wide swath of camote patch; around the hut were chayote vines laden with fruits. Below the clearing was a picturesque valley where a meandering river curled it's way with water sparkling with foam and the pine trees roared when the north wind passed by.

"I believe you feel sad and lonely," Lacuasan told Father. Although Father carried a higher Rankin their outfit, Lacuasan simply called Father by his nickname, Andy. Father liked it that way.

There was evening when Father and Lacuasan spent their time keeping away the seeping cold and wetness of Bauko weather by sipping tapey, the homemade rice wine of the natives.

This liquor was made with fermented rice, sweet varietals of the upland strains, sprinkled with binubudan, powdered rice with crushed ginger and yeast. Some was fermented and brewed using sweet upland corn.

"Have you ever visited our ulog before, Andy?" Lacuasan asked, his eyes sparkling like two tiny stars. Father shook his head, his curly hair waving in the cool breeze like young bamboo swaying with the wind in an August storm. Father at the time looked like a Robinson Crusoe, marooned on a lonely island in the South Pacific. He had gone a year without a haircut and was looking shabby with a long beard that covered the contours of his mouth.

"Come," Lacuasan said, "let's pay a visit!" The ulog was a square matchbox construction of bamboo, wood, and cogon with no opening except for a door to one side and reached by a movable staircase used by the maidens of Bauko every night. Here these young unmarried girls would sleep. Young boys, barely in their teens, frequented the ulog in the evenings to express their love to the maidens whom attracted them the most. If the young girl favors a relationship, she'd invite the boy to come up where they'd sleep together using a common pillow made of hardwood as big as the girl's thigh.

Sexual contact was strictly forbidden and a boy had better think twice before making ungentleman like advances towards the girl he loves. Bauko's young men are well disciplined so that mashing and even kissing and petting are absolutely taboo.

Lacuasan had to brief Father before an encounter with the girl he planned to date overnight. At first, Father was uneasy because he was completely ignorant of the customs of the places. But, with much tapey in his blood, he regained his courage and bravado.

Young Filipinos, they say, are fast lovers and Father did not find it hard to start. That was how he came to meet Maila. To him, Maila appeared a different breed from the rest of the girls; she was clean and neat and properly dressed in the native costume. Her hair carried a special scent like the ilang-ilang flower nipped as a bud, and a carnation petal adorned her way brownish hair. Her skin was flawless, reddish-white, and she looked like a goddess standing atop a boulder caressed by the sweet mountain air.

Maila was a half-breed, American blended with Igorot blood. Before the Great Wr she was a senior in a high school ran by Belgian sisters in Baguio. She spoke English fluently with an accent, and it was not long before Father learned that this mountain beauty was indeed very bright and intelligent. Father also found out that she was a student writer, the editor of her school paper, The Baguio Breeze.

Father was deeply impressed during the first meeting with Maila. From the start, Father enjoyed her company because, besides being a good conversationalist, she was adept at literature and could recite pieces of classic poetry from Walt Whitman to Tagore. Father fell in love with Maila on that first evening, their very first encounter.

Maila laughed loudly when father proposed to her. "You're a lowlander," she said. "I hail from a land above the clouds. How can that be possible? Shal, I stoop so easily li,e a giant from the sky to love a man from a civilized world? I'm of Igorot stock, looked down on by you lowlanders."

"No, we can never meet, " she signed heavily. The dimples in her cheek sparkled like bonfire and were very attractive in my Father's sight. "You forget that we come from two different worlds, two different spheres."

A big lump in Father's throat rendered him speechless. He knew he loved Maila and nothing would keep him from loving her more He was the type who never ran from a fight. He came from a family of hardworking peasants, unafraid to face adversity or anything that taunted his pride, courage, and honor. Now was his chance to try his luck in love. Maila was the answer to his dreams and imagination.

"Love has no boundaries, Maila," Father replied, "No, not even gaps in culture, origin, heritage, creed, skin or social status are barriers to it." Maila stared at Father hard and long. She smiled shyly and Father understood that Maila loved him too. She then stood up and muttered, " Andy, here in Bauko, we possess a priceless tradition of honor. If a suitor defeats a girl in a selected competition then she is conquered. Tomorrow, as soon as the great sun rises in the east, challenge me to a race. We wil, run uphill." She pointed to a treeless hill not far from where they stood.

"I gladly accept your challenge, Father replied, his voice a little louder than usual.

The early morning was murky in Bauko. Thick fog enveloped Lacuasan's hut atop the knoll. All around, there was an endless sea of mist. In high spirits , Father trodden the dewy grass like a colt prancing in pasture. The sun shone metallic dull and it's faint beams peeped through a thin veil of mist in the eastern horizon. He stared at the sunflowers and carnations scattered in abundance over the slopes of the Bauko mountainsides.

Maila appeared suddenly at the base of the barren hill where the race was to be held. Lacuasan was to draw the starting line. Pulling his pistol from a leather holster tucked in his waist, he advised the competitors to be ready and with the bark of his gun they were to climb the hill as fast as they could.

When the gun barked, Maila darted towards the summit like a frightened deer, her legs appeared like rapid clogs spiking furiously upwards. Meanwhile, Father sped up like a jet hitting fist-sized boulders with lightening ferocity. Father knew he was exhibiting now his prowess in the century race back in his high school years when he romped away with a gold medal in the pre-war national athletic meet in Manila. The Bauko beauty gasped for breath but she was no match for the lowlander, this soldier of fortune who had drifted up to the Bauko highland to hide from Japanese hounds.

"I surrender to you, Andy," Maila calmly admitted, breathing hard. "I didn't know you were a sprinter for the first caliber." She knelt down to catch her breath.

"And so?"

"Of course, the jog is up and I am now yours," was the curt reply. That was how Father won the the heart of Maila. Gasping for breath, Father walked slowly towards her. Clutching her by the shoulders, he gazed into her eyes. They held hands as they ascended a promontory. At the summit stood a solitary pine tree casting it's shade over a clean boulder. Here they sat together.

The sun now shone clearly and resplendent. The flowers around them bid a joyous celebration. Lacuasan followed them and congratulated both victor and vanquished and to Father for winning the heart of the fastest girl in Bauko.

IN EARLY DECEMBER, a runner from Volckmann's headquarters up in Kapangan visited the two guerrilleros. He handed Father a field order instructing them to report to headquarters for further duty as the forces of General MacArthur were fast approaching the beaches at Lingayen. In January, the liberation forces tangled with the Japanese army everywhere in Luzon. The Allied Forces surrounded the enemy in the mountain provinces by placing the infantry divisions to route Yamashita's forces holed up in Kiangan. Father and Lacuasan returned to their respective outfits to join the bloody encounters with Japanese soldiers in Bessang, Lepanto, and Kayan, the last being but a stone's throw from Bauko. In late August, the Americans issues an ultimatum to Yamashita's forces to surrender. That after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki where thousands of Japanese were killed by atomic bombs. Yamashita had to surrender unconditionally.

The GIs boarded the jeep with Lacuasan at the wheel. Father waved at the Bauko beauties as the jeep moved away. Maila and the others waved back. He caught Maila's eyes supplicating. She had not stopped crying since their hands parted in a muted farewell. Looking back once more, he thought he saw Maila's lips, parted, imploring him to return. But the jeep made a sharp turn at the fork in the road and they were met by a strong wind from the vegetable fields lining the road, accentuating the fact that the poblacion was already behind them.

With the surrender of the wily Tiger of Malaysia and his forces, after the last prisoners of war were settled in camps in the lowlands, Father and Lakuasan hurriedly left for Bauko for a brief respite. Maila and her friends arranged a homecoming celebration for the two soldiers. That night the moon was big and round and the cool Bauko air hovered over the schoolhouse where the lively event was to be held.

On a clear Sunday morning, after the sun had dissipated the thick fog enveloping the Bauko skyline, Maila and her friends stood in front of the schoolhouse to bid Father and Lacuasan goodbye. The two GIs had a new assignment somewhere in La Union.

"Of course, I shall return," Father calmly told Maila, clutching her cold hands tightly. His lips quivered and Maila, shaking with grief, placed a lei of fresh everlasting flowers over Father's neck. She was sobbing so hard as Father consoled hee by lightly patting her back.

This short story is authored by Yolanda V. Ablang taken from Ilocano Harvest (a collection of short stories in English by Ilocano Authors). Edited by Pelagio Alcantara and Miguel S. Diaz. Published by New Day Publishing, 1988, in Quezon City.

Photos are not mine, but taken from the Internet, including australianmuseum.net.au

Additional editing done by myself.

#philippines#ilocano#literature#womenwriters#heritage#mountains#lovestory#country#20th century#filipino#filipina#baguio

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Philippines’ ferocious lockdown lingers on, despite uncertain benefits

Four months and counting

The Philippines’ fierce lockdown drags on, despite uncertain benefits

Enforcement has been vigorous but patchy

“I’M CONSTANTLY AFRAID that we will get infected,” frets Diverson Bloso, “We don’t have money to bring us to the hospital, in case that happened.” A messenger at a printing press in Quezon City, part of Manila’s sprawl, he prays he keeps his job. His boss told workers that the business might have to close because of quarantine measures to stop the spread of covid-19. But at least Mr Bloso still has regular income. A woman who lost her job at an online casino says the restrictions have prevented her from attending interviews for new jobs. With her husband in jail, she worries about how she will pay the bills for her and her child. “It’s been terrible for me and my family,” she says.

The Philippines’ lockdown, among the fiercest and longest-lasting in the world, has been terrible for millions of others too. On March 16th the government imposed “Enhanced Community Quarantine” (ECQ) across the island of Luzon, home to Manila and about half the country’s 107m people. Schools and offices closed and public transport shut down. People were only supposed to leave home to buy food and other essentials. In many areas, even then, they were required to obtain a special pass from a local official to be able to move around. Other parts of the country adopted similar rules. Some provinces sealed their borders. Manila’s residents were supposed to be free again by April 13th. Instead, the lockdown has been repeatedly extended. It was relaxed slightly on June 1st to make it easier to work, but will remain in place at least until July 15th.

Enforcement has been ferocious. Some 130,000 people, including those pictured, have been arrested or fined, often for small infractions such as failing to wear a mask. Were the army and police to encounter any violent lockdown violators, instructed Rodrigo Duterte, the president, with characteristic compassion, they should “shoot them dead”. But the rules have also been applied unevenly: Manila’s police chief hosted himself a boozy birthday party in May despite the ECQ’s stipulations and a ban on liquor sales.

In the meantime, more than 50,000 Filipinos have tested positive for covid-19. The University of the Philippines reckons there might have been 3.6m cases without the lockdown, a figure the government likes to trumpet. The number of deaths each day has dropped sharply since late March, and the ECQ bought the government time to ramp up laboratory capacity and to ready beds for patients. But the number of cases detected each day has been rising fast, despite a relative dearth of testing.

The Department of Health’s response to the virus has been plagued by “irregularities and anomalies” that have attracted the attention of the government ombudsman. An investigation is under way into confused reporting of infections and delays in purchasing protective equipment for health-care workers, among other matters.

This bureaucratic fiasco and the uncertainty over case numbers may help to explain why the lockdowns have lasted so long. They have been lifted in some cities outside Luzon, only to be reimposed when cases began rising wildly. Ronald Mendoza of Ateneo de Manila University argues for more targeted quarantines. Metaphorically speaking the government has been using an axe, he reckons, when it really needs only a scalpel.

Relaxing restrictions should soothe the country’s pummelled economy: the World Bank forecasts that it will shrink by almost 2% this year. The coronavirus has brought to an end 84 quarters of uninterrupted growth in the Philippines. The quarantine on Luzon alone may displace 11m workers from their jobs, reckons IBON, a research firm in Manila. And the lifelines that helped Filipinos stay afloat during the global financial crisis are fraying, too: remittances from Filipinos working abroad, as domestic helpers, nurses and the like, look set to fall by a fifth this year.

According to surveys carried out in May via mobile phone by Social Weather Stations (SWS), a pollster, 83% of working-age Filipinos say their quality of life has declined versus a year ago. That is the worst result in the 37 years that SWS has been conducting surveys. The government’s efforts to help have been as patchy as the lockdowns. It has distributed 200bn pesos ($4bn) to 18m poor families. But delays have beset other schemes, including one offering wage subsidies for employees at small and medium-sized businesses.

Mr Duterte’s priority appears to be boosting his own authority. A temporary law, approved by Congress in March but allowed to expire in June, gave him special powers to deal with the pandemic. On July 3rd he signed into law a sweeping anti-terrorism bill which, among other things, allows suspects to be detained without a judge’s approval for up to 14 days. How this will help the Philippines through its current trauma is anyone’s guess. ■

Editor’s note: Some of our covid-19 coverage is free for readers of The Economist Today, our daily newsletter. For more stories and our pandemic tracker, see our hub

This article appeared in the Asia section of the print edition under the headline "Four months and counting"

https://ift.tt/322zpds

0 notes

Text

Blog Post #4: Social Mirrors

Chosen person: Lorenzo Lagamon

How I think they see me

In hindsight, Enzo and I are relatively new friends. We met because of the Ateneo Debate Society (ADS), an organization that only accepted me midway through the 1st semester. Although we had met by that time, we only really started talking in November, when the topic of crushes was brought about. I think those contexts, debate and crushes, really reflect in how Enzo thinks of me.

I think Enzo thinks I’m happy. Although I have been upset and express my sadness to him, I normally show a very enthusiastic disposition to the ADS. By extension, he sees that side of me as well.

However, in my lamenting about my crush he sees a hopeless romantic. Someone who loves very quickly and very hard.

I’d like to believe that he sees me as someone who is loving and caring, not only to my crush of course, but to my friends. I feel like I sacrifice and listen to my friends, and I give them kind acts of service. So in summary, a good friend.

I hope he sees me as a shoulder to lean on or the go-to person when talking about his day, because that’s definitely how I see him!

I also think he would see me as his best friend in the ADS, as in the short time we’ve known each other, we’ve been through a lot. Through numerous debate tournaments, training and meals out, we’ve become a lot closer. I think he thinks of me this way, because that’s how I think of him.

The more I write, the more I realize that my relationship with Enzo is one of reciprocity. I would like to believe that the way he views me is the way I view him.

And honestly if that’s the case, I should not be afraid of what he has to say.

What Enzo actually thinks of me

Irene asked me to write about her. I accepted without flinching, of course; but the immediate question I had to ask was not what is this for? Or why? But rather: well, where do I begin? After much introspection, I begin with the first time I met her. She knows this story too well, saying it again might intoxicate her. I met her in PSDC 2017. PSDC or Philippine Schools Debate Championship is an annual and national high school tournament organized by the Ateneo Debate Society. She was from Miriam College and I? A lowly and quiet school from Northern Mindanao. We were already in the knockout rounds of said competition when Irene — well, knocked me out. I remembered her face. In my head back then, she was a fierce woman with an undying fighting spirit tamed in a small stature. I feared her but at the same time I was angry at her. But by the blessings of the mysterious mechanisms of this universe, two different people from two very distant places now find themselves friends in the Ateneo. I always believed I would know her only as the girl who knocked me out of a tournament — but as a student of the Social Sciences, I should know better and remember that people are more than your first impressions. Over the course of our Freshman year in Ateneo, I’ve come to know Irene not just as a strong and powerful lady — but one who is too human as well. I have seen her cry because of love and the absence thereof. I have seen her laugh at the perfect moment and in the face of adversity. I have seen her dress up really well on many days. I have seen her wear shorts and a shirt too big on most. I have seen the rigour and the brilliance that make up the flames of her fierceness. I have seen the child and the longing that comprise her incessant: I want kiss (but only from a specific person, of course — whose name shall be forever redacted). Irene is brave but she is human. She is loving and thoughtful but she is human. She can sing really well — but she is human. Why do I have to make this caveat? Because oftentimes, plenty around her forget that in all her talents and amidst her commanding presence — Irene is still human too. She is brave, she is a fortress — but every once in a while, she allows herself to fall like Jericho. She is loving and thoughtful, she is patient — but sometimes she will fight you with aggression if you step out of line. She can sing really well, and she plays instruments too — but sometimes she goes off-key and her chords are played at the wrong tempo. I make these important caveats not out of spite but as a reminder that we oft neglect the humanity in heroes. They are heroes but they are human (and yet they are heroes still). I write of Irene’s strengths and I write of her imperfections not because I hate her, quite the opposite: but because truly loving someone means you see them for the human that that they are. Watch her walk the sacred halls of Schmitt, brave the torrential crowd at SecWalk, or eat her homemade vegetarian meal at Gonzaga Up, or wait for someone (a specific someone) in Matteo Ricci. Listen to her light up as she tells you how her day has been, taste the joy she pours on her poetry, and see her tears dry as she picks herself up. I sometimes catch myself writing in hyperbole or with one too many metaphors. I am in perpetual search for adverbs and synonyms. Today, I do not end that search. I could not find a prettier word to replace: very strong. She is very strong? Well, she is; but I do not want to end with that. Perhaps the closest approximate right now is: she is Irene — the toughest, most loving, most caring soul that knocked me out.

Reflection

I know Enzo to be a poetic person. So, I expected a level of flair from his write-up. What I didn’t expect is a full PDF with a header and all. Admittedly, the way we wrote our respective texts is very different, and the word choice is contrasting as well. While I expected words like, hopeless romantic, or good friend, he chose the word ‘strong’ as his motif.

Enzo even went back further than I did. It’s true that we interacted for the first time in a high school debate tournament a few years before college started, and I understand why that’s his first impression of me.

He gives no mention of me being a generally happy person.

I’m unsure if this means he doesn’t think I’m a happy person or if it’s a detail he simply chose to omit. Now that I think about it, perhaps I have ranted too many times to him for me to be seen as a definitively happy individual.

He does however, imply my hopeless romantic nature. He’s not very direct, and uses inside jokes to refer to my woes of my crush.

And, almost with relief as I read it, he does agree that I am loving and caring. For vain reasons, I’m glad this is the case. I quite honestly try very hard to make sure people think this way of me. That’s not to say it’s disingenuous, but it’s definitely crafted.

I think after comparing both of our outputs, only the words used differ but the essence stays rather the same. I’m glad this is the case because it means I know Enzo well enough, and he knows me too.

0 notes

Text

I Was Bullied In High School

When the Ateneo bullying scandal took off, social media was buzzing with insights about bullying.

Suddenly, everyone cared.

And while the fiery conversation about it is amazing, we know deep down that nothing would’ve been done about it if it didn’t catch fire like it did.

I’m no stranger to bullying. In fact, I’d like to believe that a huge chunk of who I turned out to be as an adult was brought about my emotional struggles as a bullied teenager.

Nope, I wasn’t kicked around--not physically at least. But boy, the memories of my bruised teenage heart is still so vivid to me.

Old friends became enemies. Anonymous hate mails were sent on a daily basis. I was called ugly. Lots of times stupid. People questioned and laughed at my passions. They said they wanted to impale me with a huge stick because I was a pig.

And I’m pretty sure there’s more I haven’t heard of.

Some time in Senior Year, shit just got too much to handle for me. I’d cry every morning before getting up because I just didn’t want to go to school.

And nope, it wasn’t because school was hard.

I was just fed up with hearing shit being said about me and my friends. Worse, I’d also hear the gossipy moms talk shit about me too.

The fruits didn’t fall far from their trees, I guess.

I don’t really know why I never brought these things up to my teachers back then. Maybe I didn’t trust them enough? I was so badly naïve? I feared that more bullying will come after speaking up?

Or I just somewhat feared that even if we did settle things, nothing would change. Because these kids were favorites.

The minute high school was over, I decided that I’m going to change my life and myself.

I went to college. Achieved a lot. Graduated with honors. And became a fiercely assertive person--the person I wish I was when I was at my lowest in high school.

Looking back, I regret that I didn’t fight and talk back as much.

But I guess it’s alright.

Because my bullies weren’t, and still aren’t worth what I have to offer.

0 notes

Text

Just finished one of my homeworks.

I then realized that my favorite Atenean athlete also became my favorite writing prompt. I finished this essay for my creative writing work:

Under the grins of the blissful sunlight, a copper skinned being runs across the field. Seemingly without a care, the football prodigy sprints like a cheetah with the ball gracefully touching his feet. Fierce as an eagle, the striker clad in white and cobalt blue kicks the ball with all his might. The grass beneath his feet quiver as the ball ricochets towards the goalpost. A sickening second swiftly passes by. A second, a mere second... ah! What an eternity that was! Everybody was at the edge of their seats as the score changes, one-nil. The king of the field rejoices in triumph for a millisecond, then runs back to continue the fight. The booming of the drums coincide with cheers of "Go Ateneo! One big fight!" as the action unravels. Eyes stare at the 21 year old player. He's so great that the whole unviverse stares at him in awe and wonder.

Who do you think he is? He's a living legend, a bolt of lightning surging across the turf of green. He has been described as awfully amazing by a lot of people. Since his first day as a new blood on the field of the sport football, he has never failed to take away the breaths of anyone who could see him play. In all honesty, you might just say, "oh, good heavens! What did I do to have been blessed by the marvelous sight called Javier Augustine Gayoso?"

0 notes

Text

[Unitierracalifas] UT Califas fierce care ateneo, 3-25-17, 2.00-5.00 p.m.

Compañerxs,

The Universidad de la Tierra Califas' Fierce Care Ateneo will gather on Saturday, March 25, from 2.00 - 5.00 p.m. at Miss Ollie's / Swans Market (901 Washington Street, Oakland, a few blocks from the 12th Street BART station) to continue our regular, open reflection and action space to explore questions and struggles related to the emerging politics of fierce care as well as some of the questions below.

Friday, March 10 ended Native Nations Rise, a four day convergence of Indigenous peoples and allies who gathered in Washington D.C. to continue the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline as well as the several other pipelines under construction, including the Keystone XL, Trans-Pecos, Bayou Ridge, and Dakota Access. The fight, according to Kandi Mossett, is more than against one pipeline, it's about embracing a whole new way of life —one that is sustainable and is not about taking from the earth, but giving back. It is an on-going struggle. For Mossett and others it is the continuation of a five hundred year struggle against forces that take and destroy for a lifestyle that is no longer tenable. The four days of mobilization in D.C. not only confronted the destruction of shale deposits and the pipelines that the oil industry wants to use to maintain a toxic lifestyle, but also advanced a recognition that we must reclaim and invent a new, sustainable way of living. (see, Jaffe, "Next Steps in the Battle Against the Dakota Access and Keystone Pipelines")

More and more we are reminded that Indigenous communities are on the front lines of struggle. They are often the first line of defense against the rapacious and destructive extractive industries. It is this battle line that also signals that the U.S. is a settler colonial nation and as such has been and remains committed to erasing Indigenous people. The most recent persecution against the Standing Rock Sioux and others at the DAPL has made sacred site water protectors into targets of the most advanced militarized police repression, deploying sophisticated weaponry, infiltration, and surveillance while also criminalizing sacred-site water protectors in the mainstream media. The assault on Indigenous nations underscores the most critical element of settler colonialism, that is, according to Patrick Wolfe, it is "a structure, not an event." (see, Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native") J. Kehaulani Kauanui takes up Wolfe's argument to point to an "enduring indigeneity" that operates dialectically as Indigenous peoples resist all elimination efforts, and at the same time as the settler colonial structure continues into the present to "hold out" against indigeneity. (See, J. Kehaulani Kauanui, "A Structure, Not an Event.") For both Wolfe and Kauanui, Palestine is the most recent site of a violent settler colonialism advanced by a U.S. backed Zionism. To this we would add Indian-occupied Kashmir, of which Omar Bashir recently noted, "India only wants Kashmir, not its people," thus naming the settler colonial logic with its concomitant operations of elimination and containment. (see, Bashir, "India Only Wants Kashmir, Not Its People")

More recently, Lorenzo Veracini has taken up Wolfe's intervention and also asserted that both the Indigenous and non-Indigenous are now being treated roughly the same —that is as disposable people. "The working poor are growing in number almost everywhere," warns Veracini. "Like Indigenous peoples facing a settler colonial onslaught, the 'expelled' are marked as worthless. The 'systemic transformation' produces modalities of domination that look like setter colonialism." In other words, more and more people are treated as disposable and the system would prefer to eliminate them rather than convert them into exploitable labor. (see, Veracini, "Settler Colonialism's Return")

From the Zapatistas to the several battle lines against pipelines across the U.S. and other battle fronts occupied by Indigenous communities across the globe, they are at the fore front of disrupting capitalism. But, it's not the capital(ism) we originally battled against. Or, at least, our understanding of capitalism has shifted, because capitalism has reached its final crisis. There are two clear areas of analysis that more recently have exposed its limits. First, capitalism no longer has access to an inexhaustible or "cheap nature." According to Jason Moore "capitalism is historically coherent —if 'vast but weak'— from the long sixteenth century; co-produced by a 'law of value' that is a 'law' of Cheap Nature. At the core of this law is the ongoing, radically expansive, and relentlessly innovative quest to turn work/energy of the biosphere into capital (value-in-motion)." (Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life, p. 14)

Robert Kurz, and the wertkritik school that has been built around his work, is the second line of thought that recognizes capitalism is not just in yet another cyclical crisis but is nearing the limits of its internal contradiction. Kurz has taken to task the different approaches to Marx for their inability to extend Marx's critique of political economy and account for both the excesses and limits of commodity society. "Kurz, on the basis of a thoroughgoing reading of Marx," asserts Anselm Jappe, "maintained that the basic categories of the capitalist mode of production are currently losing their dynamism and have reached their 'historical limit': mankind no longer produces enough 'value.'" (see, Jappe, "Kurz: A Journey into Capitalism's Heart of Darkness," p. 397) The crucial point made by Kurz and elaborated by Jappe is that capitalism is not eternal, nor are the specific elements of capitalism, i.e., abstract labor, value, commodity, and money, timeless. "The structural mass of unemployment (other typical phenomena are dumping-wages, social welfare, people living in dumps, and related forms of destitution) indicates that the compensating historical expansionary movement of capital has come to a standstill." (see, Kurz, "Against Labour, Against Capital: Marx 2000") Kurz admonishes against mis-using Marx's categories and falling into a positivistic trap. A more complete reading and extension of Marx's insights reveal that commodity, value, and labor are not ontological, "transhistorical conditions of human existence." As much as they are neither eternal or timeless, they likewise have a history. "The appearance of labor as the substance of value is real and objective, but it is real and objective only within the modern commodity-producing system." Jappe explains,"Kurz always asserted that capitalism was disappearing along with its old adversaries, notably the workers' movement and its intellectuals who completely internalised labour and value and never looked beyond the 'integration' of workers —followed by other 'lesser' groups— into commodity society,"

Both Moore and Kurz invite us to interrogate the myth of capitalism as a never-ending system and to recognize that it has reached its limit. It can not overcome its internal contradictions given that it can no longer exploit cheap nature. But, if capitalism is gasping its last what does this mean for race and racial formations that were long believed to be essential to managing capitalism's most exploitative functions, i.e. producing surplus value via tightly controlled labor made more malleable through a brutal racial hierarchy of violent control? Does the end of capitalism signal an abandonment of the several intersecting racial regimes that helped insure its reproduction? "Race," Wolfe insists, "is colonialism speaking, in idioms whose diversity reflects the variety of unequal relationships into which Europeans have co-opted conquered populations." For Wolfe,"different racialising practices seek to maintain population-specific modes of colonial domination through time," (see, Wolfe, "Introduction," Traces of History, p. 5; 10) If settler colonialism endures as a structure that attempts to produce populations as disposable, how are we to understand this in relation to labor and race in the current moment?

Is disposability a condition of capital in its final stage or a new racial regime? "Disposability manifests," Martha Biondi reminds us, "in our larger society's apparent acceptance of high rates of premature death of young African Americans and Latinos." It is not only the school to prison pipeline, structural unemployment, and "high rates of shooting deaths" that produce disposability. (quoted in Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, From #Blacklivesmatter to Black Liberation, p. 16) It is also the way we think about water, health, and collective ways of being.

Indigenous struggles and the Black and Brown working class are and have been refusing disposability. This can be heard in the adamant battle cry proclaiming, Black lives matter! and also in the stands taken across the globe by Indigenous people and their supporters to protect the earth. Disposibility as a technology and extractivism as an operation are imbricated and proceed in violent unison as capital enters a new phase. Disposibility is marked by settler colonialism's "drive to elimination...[a] system of winner-take-all;" extractivism follows its own mandate of total depletion of all resources, also a system of grabbing everything. (Kauanui and Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism Then and Now")

Raul Zibechi analyzes the extractivist model as a new form of neoliberalism: "extractivism creates a dramatic situation —you might call it a campo without campesinos— because one part of the population is rendered useless by no longer being involved in production, by no longer being necessary to produce commodities." For Zibechi, "the extractivist model tends to generate a society without subjects. This is because there cannot be subjects within a scorched-earth model such as extractivism. There can only be objects." (see, Zibechi, "Extractivism creates a society without subjects") What does care look like at the end of capitalism? When we are longer bound by the relations of a commodity society?

South and North Bay Crew

NB: If you are not already signed-up and would like to stay connected with the emerging Universidad de la Tierra Califas community please feel free to subscribe to the Universidad de la Tierra Califas listserve at the following url <https://lists.resist.ca/cgibin/mailman/listinfo/unitierraca lifas>. Also, if you would like to review previous ateneo announcements and summaries please check out UT Califas web page. Additional information on the ateneo in general can be found at: <http://ccra.mitotedigital.org /ateneo>. Find us on tumblr at <https://uni-tierra-califas.tumblr.com>. Also follow us on twitter: @UTCalifas. Please note we will be shifting our schedule so that the Democracy Ateneo (San Jose) will convene on the fourth Saturday of every even month. The opposite, or odd month, will be reserved for the Fierce Care Ateneo (Oakland). In this way, we are making every effort to maintain an open, consistent space of insurgent learning and convivial research that covers both sides of the Bay.

--

Center for Convivial Research at Autonomy

http://ggg.vostan.net/ccra/#1

#Universidad de la Tierra Califas#Fierce Care Ateneo#Oakland#settler colonialism#Lorenzo Veracini#J. Kehaulani Kauanui#Patrick Wolfe#UniTierra Califas#UTC

1 note

·

View note

Text

[Unitierracalifas] UT Califas Fierce Care Ateneo, 7-22-17, 2.00-5.00 p.m.

Compañerxs,

The Universidad de la Tierra Califas' Fierce Care Ateneo will gather on Saturday, July 22, from 2.00 - 5.00 p.m. at Miss Ollie's / Swans Market (901 Washington Street, Oakland, a few blocks from the 12th Street BART station) to continue our regular, open reflection and action space to explore questions and struggles related to the emerging politics of fierce care as well as some of the questions below.

Recently academics in service of the military industrial complex put forward a theory of military engagement that warns dominant military powers of the day, i.e. the U.S. and by extension Israel, to recognize that today's most profound military challenge emanates from "urbanization," that is the production of fragile and feral cities ("characterized by violence and disorder"). Not surprisingly, the cities that militaries must protect are the smart cities (with "technology fully integrated"), i.e. those cities like San Francisco, London, Barcelona, and Tel Aviv, that are organized around technologies and related services designed for the digerati and the lifestyle they enjoy. (see, Williams and Selle, "Military Contingencies in Megacities and Sub-Megacities.")

It's hardly a new thesis much less a new concern or practice. Military might has been aware of the threats that enemies bunkered in cities pose and the difficulties inherent in urban warfare. For some time now Raul Zibechi has reminded us of how present day "superpowers" worry about the expanding urban periphery, the zones of non-being both on the edges of major metropolitan centers and in the periphery more generally. (see, Zibechi, "Subterranean echos: Resistance and politics 'desde el Sótano'") Locally, the increasingly visible militarization of urban police departments reflects a growing investment in low intensity war as a strategy to control urban populations. What we witness is more than simply an increase in the introduction of sophisticated new armaments filtered back into police departments from the military. As families with deep roots in Oakland, for example, are displaced to outlying zones such as Vallejo and Stockton, paramilitary-like formations and strategies ratchet up violence that targets specific individuals, invades homes, and disrupts family relations. More and more state violence strikes in broad daylight as young people are gunned down walking to the store or chased off roads by multi-agency task forces, as in the cases of Colby Friday (8-12-2016) and James Rivera Jr. (7-22-2010).

What is worthy of note in this new global formulation of "contemporary Stalingrads" is the tacit recognition of the amount of inequality and the intensity of its production in the current capitalist conjuncture. In other words, elites and the military ranks in their service recognize how capitalism is producing an increasingly "dangerous" population behind growing numbers of "sheet-metal forests." (see, Williams and Selle, "Military Contingencies in Megacities and Sub-Megacities.") Indeed, this becomes a moment in the articulation of a new racial spatial regime. In this context, it is worth noting the recent arms deals of the Trump administration with Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Taiwan. Worth billions, these weapons are largely manufactured in the U.S. and are backed by what Robert Kurz reminds us is military bullion, from the gold dollar to the arms dollar. According to Kurz, "the dollar maintained its function as world currency through the mutation from the gold dollar to the arms dollar. And the strategic nature of global wars in the 1990s and turn of the century in the Middle East (in the Balkans and in Afghanistan) was directed at preserving the myth of the safe haven via the demonstration of the ability to intervene militarily on a global scale, thereby also securing the dollar as world currency." (see, R. Kurz, "World Power and World Money: The Economic Function of the U.S. Military Machine within Global Capitalism and the Background of the New Financial Crisis")

Much more needs to be said about the military strategy currently being developed in response to the production of mega-cities and sub mega-cities, i.e. urbanization. Read genealogically, the present focus on urbanization presents as simply another justification for a greater commitment to invest in counter insurgency strategies and low intensity conflict against civilian populations in regions of the world that still have strategic interests for the U.S. More to the point, these strategies and investments in social control economies are increasingly directed at historically under-represented populations in the U.S. Against this onslaught, it is the practices of care, the nurturing that makes survival possible, that poses the greatest threat by communities sheltering in "sheet-metal forests" or even those sub-terranean networks of care that are almost entirely invisible in the "concrete canyons" of smart cities. If the rebel army has always relied on care and strong bonds with the community to survive, perhaps it is these networks that define the resistance in the present moment, more than ideology and identification, flags and formations.

Strategies of capitalism designed to dismantle systems, networks, and practices of care work in tandem with militarization organized as counterinsurgency against a local population. Precarias a la Deriva alert us that women in Madrid's urban periphery have been creatively responding to the system's efforts to dismantle care. They warn that precarity results from four trajectories: the dismantling of of the Welfare State towards a shift to strategies of "containment of subjects of risk;" the dismantling of community spaces and expansion of commercial spaces, paralleled by the "hegemony of the car;" the dismantling of systems and skills to grow and share food, produce clothing and other necessities, a process that works hand in hand with the rise of fast food and prepared food; and the invasion aimed at time, resources, recognition, and desire for caring for children, elderly, and infirmed. (see, Precarias a la Deriva, "A Very Careful Strike-Four Hypotheses") Thus, precarity, as a current strategy of capitalism is often designated, results when areas of care in our everyday lives are privatized and no longer in our collective control. But despite this reality, people, especially women, refuse to abandon the obligations of care.

Not only are we able to recognize and remain committed to care; we find at times it can be fierce. What distinguishes care —that is the everyday efforts to nurture and be nurtured by the people around us— with other practices we are beginning to come to understand as fierce care? We refuse to abandon what we generally think of care. We expect people to be thoughtful, to worry about each other, to find ways to support, nurture, and heal those around us. But, more than that there is a growing awareness of the necessity to directly confront forces and systems of violence that intentionally target specific folks, disrupt the community, dismantle the social infrastructure, and unweave the social fabric.

In Stockton, mothers whose grown children have been killed by the state weave a complex fabric of refusal and care. Immediately following the killing of Colby Friday last August by Stockton Police officer David Wells, Dionne Smith, the mother of James Rivera Jr. who had been killed by Stockton Police six years earlier, went to the spot where Colby had been killed, and with others refused to leave —watching over the spot for two weeks and protecting the community memorial until Colby’s body was in the ground. Colby’s mother, Denise Friday, who lives two hours away in Hayward, also returns to the spot regularly, to sit and engage neighbors, refusing erasure and the fear that comes when police attempt to impose narratives and silence. These acts of vigil rest beneath the community gatherings and speak outs where mothers gather to seek and define justice; they are the quiet beneath the protests and the arrests. When school let out across California in early June and the distribution of school lunches was discontinued for summer, these same mothers began gathering once a week making dozens and dozens of brown bag lunches and handing them out to local children to help bridge the hunger of children in summer when the schools shut down. When there was extra lunches, they distributed them to the houseless community gathered under the highway overpass, or in one instance to people displaced from their apartments by fire earlier that day. As August and the one year anniversary of the killing of Colby Friday approaches, these mothers are raising funds for a back-to-school backpack drive (Colby Friday - Backpack Drive). Colby’s school age daughters dreamed the project together: the August prior, their father had been killed just before they all had a chance to get their back-to-school supplies together. In response a year later, their act of organizing supplies both exposes and remembers the stolen life of Colby, and reaches out to other children and families to share supplies. These interconnected acts mark a commitment to confront forces of violence to protect family and community and at the same time create space for everyday care. These are the moments where the care is fierce.

We retell this story and we are reminded of another story from Oaxaca —in Oaxaca, comrades tell us, when we hear bullets being fired, we don’t run away, we run to the sound of the bullets to find each other and together discover a way to stop them. As our comrades in Uni Tierra Oaxaca recently reflected: we must come together and listen, recognizing that we must learn from each other as an act of sharing and care —rather than one seeking to crush the other. This too is a fierce care.

South and North Bay Crew

NB: If you are not already signed-up and would like to stay connected with the emerging Universidad de la Tierra Califas community please feel free to subscribe to the Universidad de la Tierra Califas listserve at the following url <https://lists.resist.ca/cgibi n/mailman/listinfo/unitierraca lifas>. Also, if you would like to review previous ateneo announcements and summaries please check out UT Califas web page. Additional information on the ateneo in general can be found at: <http://ccra.mitotedigital.org /ateneo>. Find us on tumblr at <https://uni-tierra-califas.tu mblr.com>. Also follow us on twitter: @UTCalifas. Please note we will be shifting our schedule so that the Democracy Ateneo (San Jose) will convene on the fourth Saturday of every even month. The opposite, or odd month, will be reserved for the Fierce Care Ateneo (Oakland). In this way, we are making every effort to maintain an open, consistent space of insurgent learning and convivial research that covers both sides of the Bay.

1 note

·

View note

Text

[Unitierracalifas] UT Califas Fierce Care ateneo, 01.28.17, 2.00-5.00 p.m

Compañerxs

The Universidad de la Tierra Califas' Fierce Care Ateneo will gather on Saturday, January 28, from 2.00 - 5.00 p.m. at Miss Ollie's / Swans Market (901 Washington Street, Oakland, a few blocks from the 12th Street BART station) to continue our regular, open reflection and action space to explore questions and struggles related to the emerging politics of fierce care as well as some of the questions below.

J20 arrived with full streets. As promised, we witnessed mobilizations from all quarters with a wide array of constituencies and types of action engaged. The energy began percolating once the election results were clear and it was evident that the nation would have to endure at least four years of Donald Trump's presidency. The convergences, protests, student walk-outs, strikes, (such as the one voted on J19 by the dock workers in the seven ports of California) and direct actions in streets, on railway tracks, and a range of public spaces across America including those that targeted corporate sites colluding with or at the center of a right wing back lash were noteworthy and necessary.

The day after the week of marches and mobilizations, especially and including the Women’s March, begs a critical question that everyone has already been asking: after the marches what next? And what exactly happened over the week with the culmination of the mobilization on Saturday? The Women's March on Washington and the mobilizations across the country far outweighed the inauguration and the juxtaposition confirmed what we already know: that while the Trump administration and it's bombastic claim to "make America great again" does not represent large numbers of the American population, there is a repression descending that will impact us all. The bumbling mendacity of the transition team not withstanding, the Trump presidency represents the extreme of American arrogance, an attitude that reflects the most shrill notes of American (neo)liberalism.

Some argue that despite the spectacular success of the Women's march, we should be cautious about what it represents especially noting how it possibly signals the privatization of struggle given the dominance of the non-profit sector in all facets of the effort. We have also noticed that many news channels celebrated the march as the beginning of a “social movement,” a strategic claim in the professionalized joust over words and numbers between Trump and the press. The march was notable for the participation of ordinary women and their supporters, but mainstream participation from a disproportionately white crowd can also portend a certain level of de-politicization even though it is actually a profound moment of civic engagement. The question is what to do with this contradiction in a moment when we must (re)build grassroots institutions. By grassroots institutions we do not mean NGOs or 501(c)3s, rather we mean those moments when folks claim the arts of self-governance in locally rooted efforts by relying on what they already know —citizens actively making decisions not about their security or defense, but about their regeneration and the safety/space required for it. "Although the majority is not accustomed to self-government," explains Gustavo Esteva, "the impulse is profound and general. No one needs to be trained to do it. It begins at home when we create the conditions for the whole family, even young children and the elderly, to participate in the decisions that affect everyone. It then moves to the condominium, the street, the neighborhood, to all the spheres of reality in which every person moves." (see, Esteva, "Aprender a gobernarnos" <http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2017/01/16/opinion/016a1pol>)

The inauguration speech left little doubt that the Trump administration will invest heavily in a repressive apparatus to manage the mobilized outrage that will only grow as Trump and his cronies loot what they can as they can. It should be of no surprise who Trump and the white supremacists he empowers around him will blame for the violence across the country. As he stated in his inaugural: "And the crime, and the gangs, and the drugs that have stolen too many lives and robbed our country of so much unrealized potential. This American carnage stops right here and stops right now." No matter how clumsy it might be, it still signals a commitment to blame the victims. Kali Akuno of the Malcom X Grassroots Movement warns, "all of us, the veterans and rookies of struggle must get prepared for the worse —massive surveillance, repression, imprisonment, isolation, and assassination. We would be fools to take the new situation lightly. We must learn, really learn, from the failures of societies and movements in the past that failed to fully challenge white nationalism and fascism as they emerge, and even more so when they get a grasp of power. We have entered a period where sacrifice, self-sacrifice of the highest order, is imperative. If we don't view the situation this way, and resist as if our lives depended upon it (which they in fact do), we will find ourselves either back in the 16th century or extinct. So, people should expect intense repression and get prepared to make tremendous sacrifices." (see, "How to Prepare for the 'Trumpocalypse': Notes from an Organizer"<http://www.telesurtv.net/…/How-to-Prepare-for-the-Trumpocal…>) From across the nation, groups working on the ground brace for an anticipated spike in violence: deportations and the breaking up of families and communities, the ramping up of militarized policing, incarceration and surveillance, and political repression in myriad forms. Groups targeted during the campaign and their allies have organized sanctuary spaces and have begun implementing defense strategies. Beyond national borders, we brace for the legitimatization of more violence, including those violences exacted through increased settlements in Palestine and escalating tensions with Iran.

Reclaiming America through enhanced security measures, it seems abundantly clear to most that Trump's presidency will usher in a new era of militarized violence. But, the violence has been with us. Many have been contesting it for generations. And there seemed to be no respite with the Obama presidency. Many mainstream Americans, for example, have not been completely aware of the price paid by communities defending mother earth, especially the cost borne by communities confronting extractive industries directly. For those disenfranchised by the neoliberal machine and engaged in these struggles for survival, the violence is everywhere —in the privatization and poisoning of water, the destruction of forests, the infiltration of crops by genetically modified agents, the poisoning of the air including from the very paint on the walls in homes of primarily Black and Brown communities. (see, "Fruitvale District Has Highest Levels of Lead Poisoning in California" <https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2017/01/12/18795313.php>)

In the turmoil of the election and leading up to the inauguration, mobilizations have been growing across the country against pipelines. While the Whitehouse.gov website quickly scrubbed all references to many social justice issues including climate change, angry citizens and Indigenous communities have joined forces in the Trans-pecos region and extended the efforts in Standing Rock to stop yet another pipeline, declaring a moratorium on environmentally destructive drilling and pipelines. (see, Derek Royden, "Fighting the Black Snake at Two Rivers: How Standing Rock-style protest came to west Texas" <http://www.nationofchange.org/…/fighting-black-snake-two-r…/>) The sacrifices of Indigenous communities at the front lines of the battle to protect the earth are gaining strength and visibility in the U.S., and continue to be central to Indigenous resistances and struggles for survival across Mexico and the rest of Latin America. But the costs have been great. On January 15, Isidro Baldenegro López, a Tarahumara who dedicated his life to protecting the forests in his native Chihuahua was shot to death by a lone gunman. Baldenegro's assassination recalls the death of Berta Caceres (March 2016) who was also struck down and taken from us for her tireless devotion to the environment and her community. (see, Nina Lakhani, "Second winner of environmental prize killed months after Berta Cáceres death."

<https://www.theguardian.com/…/isidro-baldenegro-lopez-kille…>) Both "community leaders" had earned world-wide recognition for their work. Yet the awards and accolades from people and institutions eager to find climate solutions could not prevent their murder. Even as the climate accords are being dismantled at pace with other protective measures including national health care, we are forced to interrogate the role of large institutions in protecting those on the frontlines of climate change. How can we reclaim our communities against such senseless and cynical violence by those few who only know to plunder, to take for themselves. Global Witness' "On Dangerous Ground" reports that "more than three people were killed a week in 2015 defending their land, forests, and rivers against destructive industries." In the investigation, Global Witness "documented 185 killings across 16 countries —by far the highest annual death toll on record and more than double the number of journalists killed in the same period." Brazil alone witnessed 50 killings of people fighting forms of extratavist capital in 2015. (see, "On Dangerous Ground" <https://www.globalwitness.org/en/reports/dangerous-ground/>)

There is little disagreement that Trump's acceptance speech was a blatant, bombastic populist appeal ringing the same bell he has rung since he entered the race: to make America great again. But what does that mean exactly? It can only mean that America will continue to enjoy its lifestyle, now even less and less available to the "middle class," at the expense of the rest of the world. And, this lifestyle will be maintained through violence —a violent apparatus that has long been in place. Witness America's intolerance of the pink tide —as popular movements rose up to overturn neoliberal regimes, most notably in Uruguay to Venezuela, but even washing up on the shores of Greece.

In opposition to the war and to advocate peace throughout the world W.E.B Du Bois warned that America, the nation forged through a bond between capital and labor, depended on the exploitation of the "darker peoples of the world." Du Bois explained that the thin veneer of democracy was not for working people to have a say in government as part of democratic nation. Rather, the perception of belonging to the nation worked to prevent people from recognizing that their lifestyle came at another worker's expense; they enjoy only a slightly better life as a result of the degradation of another worker in the Global South. It is this democratic despotism that makes "the nation" intolerant to independence and self-determination outside its borders even though it claims to be both the arbiter and defender of democracy. (see, W.E.B Du Bois, "African Roots of War."<https://www.globalwitness.org/en/reports/dangerous-ground/>) It is the U.S.'s insistence on "democracy" across the globe, and the commitment to impose it everywhere, that costs so many lives.