#high water (for charley patton)

Photo

10:41 PM EST February 4, 2024:

Charley Patton - "High Water Everywhere, Part 1"

From the album Love in Vain: The Old Weird Blues

(November 2023)

Last song scrobbled from iTunes at Last.fm

Giveaway with Mojo 361, with Mick and Keef on the cover

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#bob dylan#high water (for charley patton)#love and theft#released 2001#this day#they got charles darwin trapped out there on highway 5#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Photo

youtube

Bob Dylan ~ Collisioni ~ Barolo, Italy ~ July 16, 2012

1.Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat

2.It's All Over Now, Baby Blue

3.Things Have Changed

4.Tangled Up In Blue

5.Honest With Me

6.Spirit On The Water

7.The Levee's Gonna Break

8.A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall

9.High Water (For Charley Patton)

10.Simple Twist Of Fate

11.I'll Be Your Baby Tonight

12.Highway 61 Revisited

13.Forgetful Heart (Bob Dylan-Robert Hunter/Bob Dylan)

14.Thunder On The Mountain

15.Ballad Of A Thin Man

16.Like A Rolling Stone

17.All Along The Watchtower

—

18.Blowin' In The Wind

Concert # 2422 of The Never-Ending Tour. Concert # 12 of the 2012 Europe Summer Festival Tour. 2012 concert # 28.

Concert # 252 with the 21st Never-Ending Tour

Band: Bob Dylan (vocal, guitar, grand piano & keyboard), Stu Kimball (guitar), Charlie Sexton (guitar), Donnie Herron (violin, mandolin, steel guitar), Tony Garnier (bass), George Recile (drums & percussion).

1 Bob Dylan (keyboard).

2, 4-9, 12, 14-18 Bob Dylan (grand piano).

10, 11 Bob Dylan (guitar).

2-4, 6, 9, 13, 15, 18 Bob Dylan (harmonica).

7, 8 Donnie Herron (mandolin).

9 Donnie Herron (banjo).

13, 18 Donnie Herron (violin).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

i was tagged by @rhubarb-rhubarb-rhubarb (thank you so so much <333) to put my “on repeat” playlist on shuffle and list the first ten tracks, now i don’t have spotify so i can’t really do that but i’m gonna just list ten songs im obsessed with atm

It’s Ours - Kite

Gulf Winds - Joan Baez

High Water (For Charley Patton) - Bob Dylan

She’ll Be There - The Monkees (coco dolenz i am free on thursday night and would like to hang out please call me and hang out with me on thursday night when i am free)

I Had Too Much To Dream Last Night - The Electric Prunes

St. Matthew - The Monkees

Good Girls Do Bad Things - Lucia & the Best Boys

Help! - Dolly Parton (beatles cover)

Bye, Bye, Bye - Michael Nesmith and the First National Band

The Queen and the Soldier - Suzanne Vega

i am feeling too shy to tag anyone :c BUT if you want to do it you can consider yourself tagged by me, i would love to see what ya’ll are listening to! <3

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Love and Theft"-Bob Dylan

1-Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum

2-Mississippi

3-Summer Days

4-Bye and Bye

5-Lonesome Day Blues

6-Floater (Too Much To Ask)

7-High Water (For Charley Patton)

8-Moonlight

9-Honest With Me

10-Po' Boy

11-Cry A While

12-Sugar Baby

2001

🌃

0 notes

Text

youtube

Bob Dylan - High Water (For Charley Patton)

1 note

·

View note

Text

New POD DYLAN! “High Water (For Charley Patton)” from 2001’s LOVE AND THEFT w/guest Josh Lieberman! apple.co/3Oc9owC

1 note

·

View note

Photo

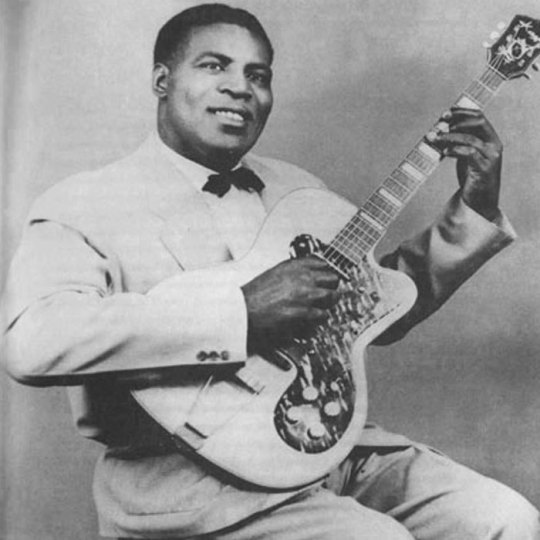

This artifact being presented is actually two songs by Charley Patton called High Water Everywhere, Part 1 & 2. The songs were recorded in late 1929 at the Paramount Studio in Grafton, Wisconsin. The medium is music recorded on vinyl records. The songs together have a length of about 6 minutes or about 3 minutes each part. These songs can be found online and specifically on YouTube. The photo of Charley Patton has a link attached that allows you to click the picture and be taken to video with both parts of the song and lyrics.

High Water Everywhere, Part 1 & 2 was written, recorded, and performed by Charley Patton. Each song lasts for about 3 minutes. The songs were recorded and distributed onto vinyl records because these were the standard form at the time. Charley was signed to Paramount Records therefore the song was recorded in a Paramount studio in Grafton, Wisconsin. He wrote and recorded it in December of 1929. Listeners can hear the guitar as the main instrument in the song because it is a classic blues instrument and an instrument that Charley Patton was a well known player of. He made these songs in 1929 in response to the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. The Mississippi River experienced extensive levee damage and led to flooding along the entire lower river in April of 1927. Around 23,000 miles of land was submerged, hundreds of thousands of people were displaced, and around 250 people died. Charley Patton described the depth of flooding and various places that went under during the flood. Charley Patton sings over the tune with catchy lyrics that give great descriptions of the places that were affected by the flood.

Charley Patton was African American and Cherokee Indigenous American as far as the consensus goes. Some believed he was a quarter white but no true evidence was found to support any claims except for his skin color. He also was believed to have a Cherokee grandmother on his mother's side. High Water Everywhere and Indigenous American literature are connected because one could think of the songs as literature from an Indigenous man. Music is just like literature because lyrics are like poetry therefore when Charley Patton was writing High Water Every, Part 1 & 2 he was writing poems about a topic that he wanted to discuss further. Charley Patton can be considered to be a good ancestor because he is leaving behind his songs about a catastrophic event so that future generations can understand what their ancestors went through in the year 1927 when the Great Mississippi Flood occurred. He is leaving behind a piece of history which could further inform his descendants in the future. Patton is also teaching his descendants to have a reverence for water and the power that it holds. Water was able to cause so much damage and sweep away everything that people knew to be home. In Part 1 of his song Patton states, “Well I’m going on to Vicksburg on a higher mound...Well I’m going on a hill, oh where water never blow”(Patton). He never seems upset towards water for the flood and he just describes what he sees the water doing. Patton describes the devastation that the water causes while still holding a respect for the water.

This musical artifact, although not a concert, touchable artifact is still very important to describe Indigenous peoples and their beliefs about water and waterways. High Water Everywhere gives the exhibition another format to learn and understand a reverence for water as also shown by the powwow necklace worn when calling for rain.

The websites listed below were used to research Charley Patton, the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, and High Water Everywhere, Parts 1 & 2. These resources provided factual evidence to describe the artifact being described for this exhibition.

https://www.britannica.com/event/Mississippi-River-flood-of-1927

http://www.msbluestrail.org/blues-trail-markers/charley-pattons-grave

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charley-Patton

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/charley-patton-mn0000166058/biography

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xL6UgyKItSo

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Blues is a music genre and musical form which was originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s by African-Americans from roots in African musical traditions, African-American work songs, and spirituals. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads. The blues form, ubiquitous in jazz, rhythm and blues and rock and roll, is characterized by the call-and-response pattern, the blues scale and specific chord progressions, of which the twelve-bar blues is the most common. Blue notes (or "worried notes"), usually thirds, fifths or sevenths flattened in pitch are also an essential part of the sound. Blues shuffles or walking bass reinforce the trance-like rhythm and form a repetitive effect known as the groove.

The lyrics of early traditional blues verses probably often consisted of a single line repeated four times. It was only in the first decades of the 20th century that the most common current structure became standard: the so-called "AAB" pattern, consisting of a line sung over the four first bars, its repetition over the next four, and then a longer concluding line over the last bars. Two of the first published blues songs, "Dallas Blues" (1912) and "Saint Louis Blues" (1914), were 12-bar blues with the AAB lyric structure. W.C. Handy wrote that he adopted this convention to avoid the monotony of lines repeated three times. The lines are often sung following a pattern closer to rhythmic talk than to a melody.Early blues frequently took the form of a loose narrative.

African-American singers voiced his or her "personal woes in a world of harsh reality: a lost love, the cruelty of police officers, oppression at the hands of white folk, [and] hard times".

This melancholy has led to the suggestion of an Igbo origin for blues because of the reputation the Igbo had throughout plantations in the Americas for their melancholic music and outlook on life when they were enslaved. The lyrics often relate troubles experienced within African American society.

For instance Blind Lemon Jefferson's "Rising High Water Blues" (1927) tells of the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927:Backwater rising, Southern peoples can't make no time

I said, backwater rising, Southern peoples can't make no time

And I can't get no hearing from that Memphis girl of mine

Although the blues gained an association with misery and oppression, the lyrics could also be humorous and raunchy:Rebecca, Rebecca, get your big legs off of me,

Rebecca, Rebecca, get your big legs off of me,

It may be sending you baby, but it's worrying the hell out of me.Hokum blues celebrated both comedic lyrical content and a boisterous, farcical performance style. Tampa Red's classic "Tight Like That" (1928) is a sly wordplay with the double meaning of being "tight" with someone coupled with a more salacious physical familiarity. Blues songs with sexually explicit lyrics were known as dirty blues. The lyrical content became slightly simpler in postwar blues, which tended to focus on relationship woes or sexual worries. Lyrical themes that frequently appeared in prewar blues, such as economic depression, farming, devils, gambling, magic, floods and drought, were less common in postwar blues.

The writer Ed Morales claimed that Yoruba mythology played a part in early blues, citing Robert Johnson's "Cross Road Blues" as a "thinly veiled reference to Eleggua, the orisha in charge of the crossroads".

However, the Christian influence was far more obvious.The repertoires of many seminal blues artists, such as Charley Patton and Skip James, included religious songs or spirituals.Reverend Gary Davis and Blind Willie Johnson are examples of artists often categorized as blues musicians for their music, although their lyrics clearly belong to spirituals.

Many elements, such as the call-and-response format and the use of blue notes, can be traced back to the music of Africa. The origins of the blues are also closely related to the religious music of the Afro-American community, the spirituals. The first appearance of the blues is often dated to after the ending of slavery and, later, the development of juke joints. It is associated with the newly acquired freedom of the former slaves. Chroniclers began to report about blues music at the dawn of the 20th century. The first publication of blues sheet music was in 1908. Blues has since evolved from unaccompanied vocal music and oral traditions of slaves into a wide variety of styles and subgenres. Blues subgenres include country blues, such as Delta blues and Piedmont blues, as well as urban blues styles such as Chicago blues and West Coast blues. World War II marked the transition from acoustic to electric blues and the progressive opening of blues music to a wider audience, especially white listeners. In the 1960s and 1970s, a hybrid form called blues rock developed, which blended blues styles with rock music.

#african music#blues#blues music#chicago blues#west coast blues#rock music#kemetic dreams#africa#juke joints#slavery#african american music#eleggua#orisha#crossroads#road blues#igbo#igbo culture#igbo music#blue note#call and response#deep south

964 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love And Theft

Released: 11 September 2001

Rating: 10/10

If there’s one thing Bob Dylan knows, it’s how to follow up a masterpiece with an even better album. This is a phenomenal record, it combines all the things Bob does best: poetic lyrics, a range of musical genres, a growling voice, and an incredibly interesting atmosphere that lingers over the whole album. I adore this record, it deserves to be spoken of as highly as ‘Highway 61 Revisited’ or ‘Blood On The Tracks’, and again proves that Bob was as prolific and trailblazing in his 60s as he was in the 1960s. (As per my last post, I will not address the ‘plagiarism’ claims here, as I feel they are baseless and reductive)

1. Tweedle Dum & Tweedle Dee - This is a great introduction to Bob’s new sound, a mix of country, rockabilly, and nostalgia. Bob’s really come into his ‘old man voice’ and the band are completely in sync. The lyrics themselves are a bit forgettable, but this fast paced opener is just effortlessly performed.

2. Mississippi - Originally an outtake from ‘Time Out Of Mind’, this is a stunningly beautiful song. The melancholy seeps out out every word and note, with Bob again acting through his voice and delivery, to portray a defeated man reminiscing and analysing his life. The music itself is surprisingly uplifting and almost at odds with the subject of the song, but it completely works. This is one of many perfect tracks on the album, and Bob’s songwriting is still untouchable.

3. Summer Days - If you had to guess, you’d say this song is from the 1950s, not 2001. A brilliant throwback, with some fantastic guitar and a great performance by Bob channelling an old blues legend. It may not be the most memorable song on the album, but it’s never a chore to hear.

4. Bye And Bye - A much more relaxed song, with a lovely musical arrangement. The lyrics are filled with happiness, and there is a great bridge that adds an interesting edge to the track. Bob’s wistful singing fits nicely, and this is just an enjoyably cheerful song.

5. Lonesome Day Blues - Perhaps an antithesis to the previous track, this is a rugged and harsh song, from the guitar licks to Bob’s gruff delivery. The song is your classic blues affair, lyrics of being rejected and mourning, but the whole song still sounds fresh and Bob always has an interesting take on the classics.

6. Floater (Too Much To Ask) - Yet another perfect track, and everything here works flawlessly. The lyrics are poetic and tell a brilliant story, but the main focus here should be on the band. The whole arrangement fills me with joy, it sounds like they’ve been playing together for centuries, and every note and instrument compliments one another and the atmosphere of the track. I could go on, but just know that this is a genius composition and all involved are at the top of their game.

7. High Water (For Charley Patton) - Not only is this the highlight of the album, it’s one of the highlights of Bob’s entire career. His way with words, creating a mood and describing an America rooted in history and mythology, are completely unmatched in both music and literature. I cannot express how perfect this track is, from the opening ‘cowboy’ sounding guitar and banjo, to Bob’s moody and haunting delivery, this is a song from both a forgotten era and yet is also somehow ahead of its time. Just listen to it on repeat, it’s fucking unbelievable.

8. Moonlight - Another slower track, with some lovely guitar and bass, and a sweet and tender Bob, almost foreshadowing is crooner turn in the following years. A great love song that is infinitely calming and romantic.

9. Honest With Me - Once again, a slower track is followed by one that sounds like a thunderstorm of guitars rolling down Highway 61. This is another song that sounds like it’s challenging you to a fight. Bob is hard as nails, the lyrics are darker, and the whole arrangement is electrified. Like the rest of the album, it’s fantastic.

10. Po’ Boy - Slowing down again, I adore this song. The lyrics are poignant and also quite funny, and for me this is Bob’s best singing on the whole record. The finger picked guitar adds an interesting layer of intimacy to the song, and all this adds up to one of my most revisited tracks from the album, and some of Bob’s most enjoyable writing from this period.

11. Cry A While - Another throwback, which blends together a few different genres and tempos, creating an incredibly interesting and ever-changing song. The lyrics are, once again, a bit of a downer (not that that’s a bad thing) but the way the band seamlessly switch up their playing is both impressive and a testament to their unrivalled talent.

12. Sugar Baby - The closing track is maybe my least favourite song, which is no bad thing as I still really enjoy it. It returns to the melancholic mood of the earlier part of the album, and is a simple arrangement with Bob growling about the past and regret. It’s still a beautiful track, and perhaps I only regard it a bit lower than the rest of the record as I know it means I’ve reached the end of one of the best albums of the 21st Century.

Verdict: It’s fairly obvious that I completely adore this record and cannot recommend it highly enough. The album may have been somewhat overlooked due to its unfortunate release date, and Bob’s late career is often ignored due to the heights of his earlier work, but this is a perfect record that shows he hadn’t slowed down or lost his touch by any means. This album goes straight into his top 10, and a handful of tracks are among his greatest achievements in songwriting and musical composition. Following this, Bob waited another 5 years before releasing yet another masterpiece, and continuing his incredible critical and artistic resurgence.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Today we remember the passing of Howlin' Wolf who Died: January 10, 1976 at the Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital in Hines, Illinois

Howlin' Wolf was a Chicago blues singer, guitarist, and harmonica player. Originally from Mississippi, he moved to Chicago in adulthood and became successful, forming a rivalry with fellow bluesman Muddy Waters. With a booming voice and imposing physical presence, he is one of the best-known Chicago blues artists.

The musician and critic Cub Koda noted, "no one could match Howlin' Wolf for the singular ability to rock the house down to the foundation while simultaneously scaring its patrons out of its wits." Producer Sam Phillips recalled, "When I heard Howlin' Wolf, I said, 'This is for me. This is where the soul of man never dies.'" Several of his songs, including "Smokestack Lightnin'", "Killing Floor" and "Spoonful", have become blues and blues rock standards. In 2011, Rolling Stone magazine ranked him number 54 on its list of the "100 Greatest Artists of All Time".

Chester Arthur Burnett was born on June 10, 1910, in White Station, Mississippi to Gertrude Jones and Leon "Dock" Burnett. He would later say that his father was "Ethiopian", while Jones had Choctaw ancestry on her father's side. He was named for Chester A. Arthur, the 21st President of the United States. His physique garnered him the nicknames "Big Foot Chester" and "Bull Cow" as a young man: he was 6 feet 3 inches tall and often weighed close to 300 pounds.

The name "Howlin' Wolf" originated from Burnett's maternal grandfather, who would admonish him for killing his grandmother's chicks from reckless squeezing by warning him that wolves in the area would come and get him; the family would continue this by calling the young man "the Wolf". The blues historian Paul Oliver wrote that Burnett once claimed to have been given his nickname by his idol Jimmie Rodgers.

In 1930, Burnett met Charley Patton, the most popular bluesman in the Mississippi Delta at the time. He would listen to Patton play nightly from outside a nearby juke joint. There he remembered Patton playing "Pony Blues", "High Water Everywhere", "A Spoonful Blues", and "Banty Rooster Blues". The two became acquainted, and soon Patton was teaching him guitar. Burnett recalled that "the first piece I ever played in my life was ... a tune about hook up my pony and saddle up my black mare"—Patton's "Pony Blues". He also learned about showmanship from Patton: "When he played his guitar, he would turn it over backwards and forwards, and throw it around over his shoulders, between his legs, throw it up in the sky". Burnett would perform the guitar tricks he learned from Patton for the rest of his life. He played with Patton often in small Delta communities.

Burnett was influenced by other popular blues performers of the time, including the Mississippi Sheiks, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Ma Rainey, Lonnie Johnson, Tampa Red, Blind Blake, and Tommy Johnson. Two of the earliest songs he mastered were Jefferson's "Match Box Blues" and Leroy Carr's "How Long, How Long Blues". The country singer Jimmie Rodgers was also an influence. Burnett tried to emulate Rodgers's "blue yodel" but found that his efforts sounded more like a growl or a howl: "I couldn't do no yodelin', so I turned to howlin'. And it's done me just fine". His harmonica playing was modeled after that of Sonny Boy Williamson II, who taught him how to play when Burnett moved to Parkin, Arkansas, in 1933.

During the 1930s, Burnett performed in the South as a solo performer and with numerous blues musicians, including Floyd Jones, Johnny Shines, Honeyboy Edwards, Sonny Boy Williamson II, Robert Johnson, Robert Lockwood, Jr., Willie Brown, Son House and Willie Johnson. By the end of the decade, he was a fixture in clubs, with a harmonica and an early electric guitar.

On April 9, 1941, he was inducted into the U.S. Army and was stationed at several bases around the country. He found it difficult to adjust to military life, and was discharged at the end of his hitch in November 3, 1943. He returned to his family, which had recently moved near West Memphis, Arkansas, and helped with the farming while also performing, as he had done in the 1930s, with Floyd Jones and others. In 1948 he formed a band, which included the guitarists Willie Johnson and Matt "Guitar" Murphy, the harmonica player Junior Parker, a pianist remembered only as "Destruction" and the drummer Willie Steele. Radio station KWEM in West Memphis began broadcasting his live performances, and he occasionally sat in with Williamson on KFFA in Helena, Arkansas.

In 1951, Ike Turner, who was a freelance talent scout, heard Howlin' Wolf in West Memphis. Turner brought him to record several songs for Sam Phillips at Memphis Recording Service (later renamed Sun Studio) and the Bihari brothers at Modern Records. Phillips praised his singing, saying, "God, what it would be worth on film to see the fervour in that man's face when he sang. His eyes would light up, you'd see the veins come out on his neck and, buddy, there was nothing on his mind but that song. He sang with his damn soul." Howlin' Wolf quickly became a local celebrity and began working with a band that included the guitarists Willie Johnson and Pat Hare. Sun Records had not yet been formed, so Phillips licensed his recording to Chess Records. Howlin' Wolf's first singles were issued by two different record companies in 1951: "Moanin' at Midnight"/"How Many More Years" released on Chess, "Riding in the Moonlight"/"Morning at Midnight," and "Passing By Blues"/"Crying at Daybreak" released on Modern's subsidiary RPM Records. In December 1951, Leonard Chess was able to secure Howlin' Wolf's contract, and at the urging of Chess, he relocated to Chicago in late 1952.

Burnett was noted for his disciplined approach to his personal finances. Having already achieved a measure of success in Memphis, he described himself as "the onliest one to drive himself up from the Delta" to Chicago, which he did, in his own car on the Blues Highway and with $4,000 in his pocket, a rare distinction for a black bluesman of the time. Although functionally illiterate into his forties, Burnett eventually returned to school, first to earn a General Educational Development (GED) diploma and later to study accounting and other business courses to help manage his career.

Burnett met his future wife, Lillie, when she attended one of his performances at a Chicago club. She and her family were urban and educated and were not involved in what was considered the unsavory world of blues musicians. Nevertheless, he was attracted to her as soon as he saw her in the audience. He immediately pursued her and won her over. According to those who knew them, the couple remained deeply in love until his death. Together, they raised two daughters Betty and Barbara, Lillie's daughters from an earlier relationship. West Cost rapper Skeme is his cousin, who was born 14 years after his death.

After he married Lillie, who was able to manage his professional finances, Burnett was so financially successful that he was able to offer band members not only a decent salary but benefits such as health insurance; this enabled him to hire his pick of available musicians and keep his band one of the best around. According to his stepdaughters, he was never financially extravagant (for instance, he drove a Pontiac station wagon rather than a more expensive, flashy car).

Burnett's health began declining in the late 1960s. He had several heart attacks and suffered bruised kidneys in a car accident in 1970. Concerned for his health, the bandleader Eddie Shaw limited him to performing 21 songs per concert.

In January 1976, Burnett checked into the Veterans Administration Hospital in Hines, Illinois, for kidney surgery. He died of complications from the procedure on January 10, 1976, at the age of 65. He was buried in Oakridge Cemetery, outside Chicago, in a plot in Section 18, on the east side of the road. His gravestone has an image of a guitar and harmonica etched into it.

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Bob Dylan - February 9, 2002 ~ Atlanta, GA ~ Soundboard

Setlist:

I Am The Man, Thomas (acoustic)

My Back Pages (acoustic) (Bob on harp and Larry on fiddle)

It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding) (acoustic) (Larry on cittern)

Searching For A Soldier's Grave (acoustic)(Bob on harp)

(song by Johnnie Wright, Jim Anglin and Jack Anglin)

Lonesome Day Blues

Lay, Lady, Lay (Larry on pedal steel)

Floater

High Water (For Charley Patton) (Larry on banjo)

It Ain't Me, Babe (acoustic) (Bob on harp)

Masters Of War (acoustic)

Tangled Up In Blue (acoustic) (Bob on harp)

Summer Days (Tony on standup bass)

Sugar Baby (Tony on standup bass)

Drifter's Escape (Bob on harp)

Rainy Day Women #12 & 35 (Larry on steel guitar)(1st encore)

Things Have Changed

Like A Rolling Stone

Forever Young (acoustic) (Bob on harp)

Honest With Me

Blowin' In The Wind (acoustic) (Bob on harp)(2nd encore)

All Along The Watchtower

Concert # 1390 of The Never-Ending Tour. Concert # 7 of the 2002 US Winter Tour. 2002 concert # 7.

Concert # 7 with the 13th Never-Ending Tour Band: Bob Dylan (vocal & guitar), Charlie Sexton (guitar), Larry Campbell (guitar, mandolin, pedal steel guitar & electric slide guitar), Tony Garnier (bass), George Recile (drums & percussion).

1–4, 9–11, 18, 20 acoustic with the band.

4, 9, 11, 14, 18, 20 Bob Dylan (harmonica).

2 Larry Campbell (fiddle).

3 Larry Campbell (bouzouki).

1, 4, 18, 20 Larry Campbell & Charlie Sexton (backup vocals).

1 note

·

View note

Text

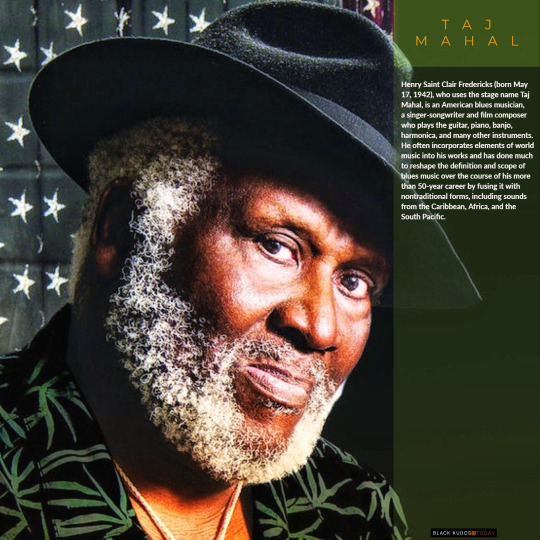

Taj Mahal

Henry Saint Clair Fredericks (born May 17, 1942), who uses the stage name Taj Mahal, is an American blues musician, a singer-songwriter and film composer who plays the guitar, piano, banjo, harmonica, and many other instruments. He often incorporates elements of world music into his works and has done much to reshape the definition and scope of blues music over the course of his more than 50-year career by fusing it with nontraditional forms, including sounds from the Caribbean, Africa, and the South Pacific.

Early life

Born Henry Saint Clair Fredericks, Jr. on May 17, 1942, in Harlem, New York, Mahal grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts. He was raised in a musical environment; his mother was a member of a local gospel choir and his father was an Afro-Caribbean jazz arranger and piano player. His family owned a shortwave radio which received music broadcasts from around the world, exposing him at an early age to world music. Early in childhood he recognized the stark differences between the popular music of his day and the music that was played in his home. He also became interested in jazz, enjoying the works of musicians such as Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk and Milt Jackson. His parents came of age during the Harlem Renaissance, instilling in their son a sense of pride in his Caribbean and African ancestry through their stories.

Because his father was a musician, his house was frequently the host of other musicians from the Caribbean, Africa, and the U.S. His father, Henry Saint Clair Fredericks Sr., was called "The Genius" by Ella Fitzgerald before starting his family. Early on, Henry Jr. developed an interest in African music, which he studied assiduously as a young man. His parents also encouraged him to pursue music, starting him out with classical piano lessons. He also studied the clarinet, trombone and harmonica. When Mahal was eleven his father was killed in an accident at his own construction company, crushed by a tractor when it flipped over. This was an extremely traumatic experience for the boy.

Mahal's mother later remarried. His stepfather owned a guitar which Taj began using at age 13 or 14, receiving his first lessons from a new neighbor from North Carolina of his own age who played acoustic blues guitar. His name was Lynwood Perry, the nephew of the famous bluesman Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup. In high school Mahal sang in a doo-wop group.

For some time Mahal thought of pursuing farming over music. He had developed a passion for farming that nearly rivaled his love of music—coming to work on a farm first at age 16. It was a dairy farm in Palmer, Massachusetts, not far from Springfield. By age nineteen he had become farm foreman, getting up a bit after 4:00 a.m. and running the place. "I milked anywhere between thirty-five and seventy cows a day. I clipped udders. I grew corn. I grew Tennessee redtop clover. Alfalfa." Mahal believes in growing one's own food, saying, "You have a whole generation of kids who think everything comes out of a box and a can, and they don't know you can grow most of your food." Because of his personal support of the family farm, Mahal regularly performs at Farm Aid concerts.

Taj Mahal, his stage name, came to him in dreams about Gandhi, India, and social tolerance. He started using it in 1959 or 1961—around the same time he began attending the University of Massachusetts. Despite having attended a vocational agriculture school, becoming a member of the National FFA Organization, and majoring in animal husbandry and minoring in veterinary science and agronomy, Mahal decided to take the route of music instead of farming. In college he led a rhythm and blues band called Taj Mahal & The Elektras and, before heading for the U.S. West Coast, he was also part of a duo with Jessie Lee Kincaid.

Career

In 1964 he moved to Santa Monica, California, and formed Rising Sons with fellow blues rock musician Ry Cooder and Jessie Lee Kincaid, landing a record deal with Columbia Records soon after. The group was one of the first interracial bands of the period, which likely made them commercially unviable. An album was never released (though a single was) and the band soon broke up, though Legacy Records did release The Rising Sons Featuring Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder in 1992 with material from that period. During this time Mahal was working with others, musicians like Howlin' Wolf, Buddy Guy, Lightnin' Hopkins, and Muddy Waters. Mahal stayed with Columbia after the Rising Sons to begin his solo career, releasing the self-titled Taj Mahal and The Natch'l Blues in 1968, and Giant Step/De Old Folks at Home with Kiowa session musician Jesse Ed Davis from Oklahoma, who played guitar and piano in 1969. During this time he and Cooder worked with the Rolling Stones, with whom he has performed at various times throughout his career. In 1968, he performed in the film The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus. He recorded a total of twelve albums for Columbia from the late 1960s into the 1970s. His work of the 1970s was especially important, in that his releases began incorporating West Indian and Caribbean music, jazz and reggae into the mix. In 1972, he acted in and wrote the film score for the movie Sounder, which starred Cicely Tyson. He reprised his role and returned as composer in the sequel, Part 2, Sounder.

In 1976 Mahal left Columbia and signed with Warner Bros. Records, recording three albums for them. One of these was another film score for 1977's Brothers; the album shares the same name. After his time with Warner Bros., he struggled to find another record contract, this being the era of heavy metal and disco music.

Stalled in his career, he decided to move to Kauai, Hawaii in 1981 and soon formed the Hula Blues Band. Originally just a group of guys getting together for fishing and a good time, the band soon began performing regularly and touring. He remained somewhat concealed from most eyes while working out of Hawaii throughout most of the 1980s before recording Taj in 1988 for Gramavision. This started a comeback of sorts for him, recording both for Gramavision and Hannibal Records during this time.

In the 1990s Mahal became deeply involved in supporting the nonprofit Music Maker Relief Foundation. As of 2019, he was still on the Foundation's advisory board.

In the 1990s he was on the Private Music label, releasing albums full of blues, pop, R&B and rock. He did collaborative works both with Eric Clapton and Etta James.

In 1998, in collaboration with renowned songwriter David Forman, producer Rick Chertoff and musicians Cyndi Lauper, Willie Nile, Joan Osborne, Rob Hyman, Garth Hudson and Levon Helm of the Band, and the Chieftains, he performed on the Americana album Largo based on the music of Antonín Dvořák.

In 1997 he won Best Contemporary Blues Album for Señor Blues at the Grammy Awards, followed by another Grammy for Shoutin' in Key in 2000. He performed the theme song to the children's television show Peep and the Big Wide World, which began broadcast in 2004.

In 2002, Mahal appeared on the Red Hot Organization's compilation album Red Hot and Riot in tribute to Nigerian afrobeat musician Fela Kuti. The Paul Heck produced album was widely acclaimed, and all proceeds from the record were donated to AIDS charities.

Taj Mahal contributed to Olmecha Supreme's 2006 album 'hedfoneresonance'. The Wellington-based group led by Mahal's son Imon Starr (Ahmen Mahal) also featured Deva Mahal on vocals.

Mahal partnered up with Keb' Mo' to release a joint album TajMo on May 5, 2017. The album has some guest appearances by Bonnie Raitt, Joe Walsh, Sheila E., and Lizz Wright, and has six original compositions and five covers, from artists and bands like John Mayer and The Who.

In 2013, Mahal appeared in the documentary film 'The Byrd Who Flew Alone', produced by Four Suns Productions. The film was about Gene Clark, one of the original Byrds, who was a friend of Mahal for many years.

In June 2017, Mahal appeared in the award-winning documentary film The American Epic Sessions, directed by Bernard MacMahon, recording Charley Patton's "High Water Everywhere" on the first electrical sound recording system from the 1920s. Mahal appeared throughout the accompanying documentary series American Epic, commenting on the 1920s rural recording artists who had a profound influence on American music and on him personally.

Musical style

Mahal leads with his thumb and middle finger when fingerpicking, rather than with his index finger as the majority of guitar players do. "I play with a flatpick," he says, "when I do a lot of blues leads." Early in his musical career Mahal studied the various styles of his favorite blues singers, including musicians like Jimmy Reed, Son House, Sleepy John Estes, Big Mama Thornton, Howlin' Wolf, Mississippi John Hurt, and Sonny Terry. He describes his hanging out at clubs like Club 47 in Massachusetts and Ash Grove in Los Angeles as "basic building blocks in the development of his music." Considered to be a scholar of blues music, his studies of ethnomusicology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst would come to introduce him further to the folk music of the Caribbean and West Africa. Over time he incorporated more and more African roots music into his musical palette, embracing elements of reggae, calypso, jazz, zydeco, R&B, gospel music, and the country blues—each of which having "served as the foundation of his unique sound." According to The Rough Guide to Rock, "It has been said that Taj Mahal was one of the first major artists, if not the very first one, to pursue the possibilities of world music. Even the blues he was playing in the early 70s – Recycling The Blues & Other Related Stuff (1972), Mo' Roots (1974) – showed an aptitude for spicing the mix with flavours that always kept him a yard or so distant from being an out-and-out blues performer." Concerning his voice, author David Evans writes that Mahal has "an extraordinary voice that ranges from gruff and gritty to smooth and sultry."

Taj Mahal believes that his 1999 album Kulanjan, which features him playing with the kora master of Mali's Griot tradition Toumani Diabate, "embodies his musical and cultural spirit arriving full circle." To him it was an experience that allowed him to reconnect with his African heritage, striking him with a sense of coming home. He even changed his name to Dadi Kouyate, the first jali name, to drive this point home. Speaking of the experience and demonstrating the breadth of his eclecticism, he has said:

The microphones are listening in on a conversation between a 350-year-old orphan and its long-lost birth parents. I've got so much other music to play. But the point is that after recording with these Africans, basically if I don't play guitar for the rest of my life, that's fine with me....With Kulanjan, I think that Afro-Americans have the opportunity to not only see the instruments and the musicians, but they also see more about their culture and recognize the faces, the walks, the hands, the voices, and the sounds that are not the blues. Afro-American audiences had their eyes really opened for the first time. This was exciting for them to make this connection and pay a little more attention to this music than before.

Taj Mahal has said he prefers to do outdoor performances, saying: "The music was designed for people to move, and it's a bit difficult after a while to have people sitting like they're watching television. That's why I like to play outdoor festivals-because people will just dance. Theatre audiences need to ask themselves: 'What the hell is going on? We're asking these musicians to come and perform and then we sit there and draw all the energy out of the air.' That's why after a while I need a rest. It's too much of a drain. Often I don't allow that. I just play to the goddess of music-and I know she's dancing."

Mahal has been quoted as saying, "Eighty-one percent of the kids listening to rap were not black kids. Once there was a tremendous amount of money involved in it ... they totally moved it over to a material side. It just went off to a terrible direction. ...You can listen to my music from front to back, and you don't ever hear me moaning and crying about how bad you done treated me. I think that style of blues and that type of tone was something that happened as a result of many white people feeling very, very guilty about what went down."

Awards

Taj Mahal has received three Grammy Awards (ten nominations) over his career.

1997 (Grammy Award) Best Contemporary Blues Album for Señor Blues

2000 (Grammy Award) Best Contemporary Blues Album for Shoutin' in Key

2006 (Blues Music Awards) Historical Album of the Year for The Essential Taj Mahal

2008 (Grammy Nomination) Best Contemporary Blues Album for Maestro

2018 (Grammy Award) Best Contemporary Blues Album for TajMo

On February 8, 2006 Taj Mahal was designated the official Blues Artist of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

In March 2006, Taj Mahal, along with his sister, the late Carole Fredericks, received the Foreign Language Advocacy Award from the Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages in recognition of their commitment to shine a spotlight on the vast potential of music to foster genuine intercultural communication.

On May 22, 2011, Taj Mahal received an honorary Doctor of Humanities degree from Wofford College in Spartanburg, South Carolina. He also made brief remarks and performed three songs. A video of the performance can be found online.

In 2014, Taj Mahal received the Americana Music Association's Lifetime Achievement award.

Discography

Albums

1968 – Taj Mahal

1968 – The Natch'l Blues

1969 – Giant Step/De Ole Folks at Home

1971 – Happy Just to Be Like I Am

1972 – Recycling The Blues & Other Related Stuff

1972 – Sounder (original soundtrack)

1973 – Oooh So Good 'n Blues

1974 – Mo' Roots

1975 – Music Keeps Me Together

1976 – Satisfied 'n Tickled Too

1976 – Music Fuh Ya'

1977 – Brothers

1977 – Evolution

1987 – Taj

1988 – Shake Sugaree

1991 – Mule Bone

1991 – Like Never Before

1993 – Dancing the Blues

1995 – Mumtaz Mahal (with V.M. Bhatt and N. Ravikiran)

1996 – Phantom Blues

1997 – Señor Blues

1998 – Sacred Island AKA Hula Blues (with The Hula Blues Band)

1999 – Blue Light Boogie

1999 – Kulanjan (with Toumani Diabaté)

2001 – Hanapepe Dream (with The Hula Blues Band)

2005 – Mkutano Meets the Culture Musical Club of Zanzibar

2008 – Maestro

2014 – Talkin' Christmas (with Blind Boys of Alabama)

2016 – Labor of Love

2017 – TajMo (with Keb' Mo')

Live albums

1971 – The Real Thing

1972 – Recycling The Blues & Other Related Stuff

1972 – Big Sur Festival - One Hand Clapping

1979 – Live & Direct

1990 – Live at Ronnie Scott's

1996 – An Evening of Acoustic Music

2000 – Shoutin' in Key

2004 – Live Catch

2015 – Taj Mahal & The Hula Blues Band: Live From Kauai

Compilation albums

1980 – Going Home

1981 – The Best of Taj Mahal, Volume 1 (Columbia)

1992 – Taj's Blues

1993 – World Music

1998 – In Progress & In Motion: 1965-1998

1999 – Blue Light Boogie

2000 – The Best of Taj Mahal

2000 – The Best of the Private Years

2001 – Sing a Happy Song: The Warner Bros. Recordings

2003 – Martin Scorsese Presents the Blues – Taj Mahal

2003 – Blues with a Feeling: The Very Best of Taj Mahal

2005 – The Essential Taj Mahal

2012 – Hidden Treasures of Taj Mahal

Various artists featuring Taj Mahal

1968 – The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus

1968 – The Rock Machine Turns You On

1970 – Fill Your Head With Rock

1985 – Conjure: Music for the Texts of Ishmael Reed

1990 – The Hot Spot – original soundtrack

1991 – Vol Pour Sidney – one title only, other tracks by Charlie Watts, Elvin Jones, Pepsi, The Lonely Bears, Lee Konitz and others.

1992 – Rising Sons Featuring Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder

1992 – Smilin' Island of Song by Cedella Marley Booker and Taj Mahal.

1993 – The Source by Ali Farka Touré (World Circuit WCD030; Hannibal 1375)

1993 – Peace Is the World Smiling

1997 – Follow the Drinking Gourd

1997 – Shakin' a Tailfeather

1998 – Scrapple – original soundtrack

1998 – Largo

1999 – Hippity Hop

2001 – "Strut" – with Jimmy Smith on his album Dot Com Blues

2002 – Jools Holland's Big Band Rhythm & Blues (Rhino) – contributing his version of "Outskirts of Town"

2002 – Will The Circle Be Unbroken, Volume III – Lead vocals on Fishin' Blues, and lead in and first verse of the title track, with Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Alison Krauss, Doc Watson

2004 – Musicmakers with Taj Mahal (Music Maker 49)

2004 – Etta Baker with Taj Mahal (Music Maker 50)

2007 – Goin' Home: A Tribute to Fats Domino (Vanguard) – contributing his version of "My Girl Josephine"

2007 – Le Cœur d'un homme by Johnny Hallyday – duet on "T'Aimer si mal", written by French best-selling novelist Marc Levy

2009 – American Horizon – with Los Cenzontles, David Hidalgo

2011 – Play The Blues Live From Lincoln Jazz Center – with Wynton Marsalis and Eric Clapton, playing on "Just a Closer Walk With Thee" and "Corrine, Corrina"

2013 – "Poye 2" – with Bassekou Kouyate and Ngoni Ba on their album Jama Ko

2013 – "Winding Down" – with Sammy Hagar, Dave Zirbel, John Cuniberti, Mona Gnader, Vic Johnson on the album Sammy Hagar & Friends

2013 – Divided & United: The Songs of the Civil War – with a version of "Down by the Riverside"

2015 – "How Can a Poor Boy?" – with Van Morrison on his album Re-working the Catalogue

2017 – Music from The American Epic Sessions: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack – contributing his version of "High Water Everywhere"

Filmography

Live DVDs

2002 – Live at Ronnie Scott's 1988

2006 – Taj Mahal/Phantom Blues Band Live at St. Lucia

2011 – Play The Blues Live From Lincoln Jazz Center – with Wynton Marsalis and Eric Clapton, playing on "Just a Closer Walk With Thee" and "Corrine, Corrina"

Movies

1972 – Sounder – as Ike

1977 – Brothers

1991 – Bill & Ted's Bogus Journey

1996 – The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus

1998 – Outside Ozona

1998 – Six Days, Seven Nights

1998 – Blues Brothers 2000

1998 – Scrapple

2000 – Songcatcher

2002 – Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood

2017 – American Epic

2017 – The American Epic Sessions

TV Shows

1977 - Saturday Night Live: Episode 048 Performer: Musical Guest

1985 - Theme song from Star Wars: Ewoks

1992 – New WKRP in Cincinnati – Moss Dies as himself

1999 – Party of Five – Fillmore Street as himself

2003 – Arthur – Big Horns George as himself

2004 – Theme song from Peep and the Big Wide World

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

High Water (for Charley Patton) - Bob Dylan

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dooley Noted - A musical journey through the mojo of a Toledo bluesman

(original version can be seen at https://toledocitypaper.com/feature/dooley-noted/)

Dooley Wilson is frustrated.

It’s 9:57 am on a cold Saturday in December and he is supposed to start playing at 10 o’clock. He has only just now stumbled out of the Toledo tundra into the cozy confines of the Glass City Cafe, which has booked him for its popular Bluegrass Breakfast music series.

“I’m so sorry I’m late,” he cries out in the direction of restaurant owner Steve Crouse, who assures him everything is fine. Wilson looks pained as a brief flash of flame passes over his smoldering dark brown eyes. No, it’s not fine. He was scheduled to start playing the blues at 10 sharp, and now he’s going to start late. And a professional should always be punctual.

Undaunted, he swallows his disappointment and, within 10 minutes, he has everything set up at the front of the restaurant which serves as the stage. Upending his battered Cunard Queen of Elizabeth canvas bag, he sorts through the contents— Halls menthol cough drops, a bottle of slippery elm supplements (“Just in case my voice goes out”), a bottle of Deja Blue water, a glass vase that serves as a tip jar and a power strip.

He plugs the power strip into his amp, a well-loved 1965 Fender Bandmaster. And then out comes the artisan’s tool— his Jay Turser electric guitar. It doesn’t have a name or anything; it’s a utensil to serve the stew of blues (“It’s a cheapo guitar, but it’s MY cheapo guitar,” he muses). He’s almost ready. He asks, and a cup of hot black coffee is delivered. After the obligatory microphone check, he sits on the edge of a worn tan suitcase and readies his guitar. It’s time to go to work.

Soon the Glass City Cafe fills with the sound of the blues— and Wilson is lost in ecstasy. He’s sitting atop the worn tan suitcase, choking the guitar neck, his angular carved-in-stone features a mask of concentration, fingers and knuckles gnarled from a lifetime of plucking strings. There’s no setlist, no backdrop, no real plan. Just a working man with an instrument sharing the gospel of what he believes is the greatest music that exists. Wilson plays the blues as if his life depends on it.

And maybe it does.

From C.J. to Dooley

Dooley Wilson does not take toast with his mozzarella cheese omelet, favoring potatoes instead. Sitting in the Glass City Cafe months later— this time as a patron— he is a bit more relaxed than he was when he played here. He still doesn’t smile much. Wilson isn’t grumpy, he just carries himself with an intensity that’s disarming. You get the feeling that he doesn’t want to be here. That’s because he lives to do one thing: Play the blues. And when he’s not playing the blues, by gum, he wants to be playing the blues.

But for now, he’ll tell his story. Now 45 years old, he was born C.J. Forgy, in West Lafayette, Indiana to James and Sandy Forgy. His parents split when he was two years old and he went to live with his maternal grandmother in Maumee. An only child, Wilson describes himself as an “artsy kid” who spent hours in his room drawing and writing.

“Everyone thought I was going to be a visual artist,” says Wilson, taking a sip of his coffee. “But along with writing, over the years I’ve let those skills atrophy,” he says, with a regretful sigh. “But I don’t know; I’m thinking about taking up drawing again for its therapeutic value.”

So what sparked his obsessive devotion to the blues? It started as musical hangups often did in the ‘80s— with a cassette. At 15, Wilson, who was teaching himself guitar and whose musical tastes at the time ran towards Led Zeppelin, walked into Camelot Music in the now-long-gone Southwyck Mall and spied a tape from Columbia Records called Legends of the Blues Vol. 1. There was something about that tape that spoke to him.

He picked it up and looked at the back. As-yet unfamiliar names like Bo Carter, Blind Willie Johnson, Charley Patton, and Leroy Carr stared out at him from the tracklisting. Robert Johnson— he knew that name from an interview he’d read with Jimmy Page and he was fascinated by the infamous story about Johnson reputedly getting his blues talent while making a deal with the devil at a crossroads. Maybe it was the ghost of Johnson himself speaking to Wilson that day in Camelot Music. All he knew is that he had to buy it.

When he got home, he popped the tape into his boom box, and something in the universe shifted. At that moment, C.J. Forgy ceased to exist and the bluesman named Dooley Wilson was born.

“That anthology started this mystique and passion I had for this music,” says Wilson, in between forkfuls of omelet. “It just spoke to my angst-ridden soul at the time and I had never heard anything so authentic, so human, so real. Take Son House’s song ‘Death Letter,’ which is on that anthology. It’s taken from his 1965 Columbia session and it’s just this amazing song about how a man gets a letter saying that the woman he loves is dead. It’s just…” Wilson often trails off when he talks about the blues; yet another reason why he’d much rather play you a song than talk about it.

From that fateful moment, the blues wasn’t just a preferred style of music to listen to or to learn to play… it became, at that time, a life choice.

“I decided I’m going to devote my life to being some kind of bluesman like Fred MacDowell or Son House,” says Wilson. “It became much more important to me than making a living. If you weren’t dead and black, I couldn’t be bothered to listen to you.”

Henry & June

By the way, where did that name Dooley Wilson come from? Wilson smiles broadly with a touch of sheepishness. He was setting up one of his earliest gigs, at the famous East-side haunt Frankie’s, and his buddy Lance Hulsey (currently the leader of Toledo rockabilly outfit Kentucky Chrome)— who Wilson played with his first band, a heavy metal project called Harlequin— said that the promoter needed to know what to call him… and C.J. Forgy didn’t exactly sound bluesy. So the young musician, right there, decided on the name Dooley Wilson in homage to the actor and musician of the same name, famous for playing the character Sam in Casablanca. Dooley Wilson is now his legal name. He cashes checks with that moniker.

With a new name under his bluesman’s belt, the then-recent Maumee High School (Class of 1992) graduate needed a band that would let him explore the blues the way he wanted to. The result was Henry & June, a heavy blues ensemble that Wilson formed with his good friend Jimmy Danger. They got the band name from a recently released biopic of Henry Miller, one of Wilson’s favorite authors.

“I was obsessed with the blues at that time, but I’m still incapable of playing it correctly,” says Wilson, draining his coffee cup. “I was really struggling to learn how to play blues the way it was meant to be played.”

But even as he worked to unravel the mysteries of Deep South blues, Wilson was experiencing something unexpected: Success. Henry & June had released a single called “Going Back to Memphis” on Detroit label Human Fly Records, and the song was attracting a lot of heat. The popular band The Laughing Hyenas— which featured former Necros member Todd Swalla, who would go on to play with Wilson in his later outfit Boogaloosa Prayer— were big fans of the song and were trying to get Henry and June signed to Touch and Go Records. Some cat named Jack White, who had a little band called The White Stripes, also was a big Henry and June fan and began covering “Going Back to Memphis” in concert.

“We were kind of a hot, cult thing on the scene in Detroit,” says Wilson, thanking the Glass City Cafe waitress as she refills his coffee. “Jack White wasn’t the only cool person in Detroit who knew who we were though, of course, he became the most famous one. Judah Bower of the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion put out a cover of the single on his side project called 20 Miles. I heard The Von Bondies used to cover ‘Going Back to Memphis.’ It’s a really fun, simple, dumb song.”

And then right when things started to go well for Henry & June, it all went wrong. The blues were supposed to feel like freedom and suddenly Wilson and the rest of the band began to feel decidedly trapped.

“Jimmy in particular felt like things were getting stagnant,” says Wilson. “Things were going good for us but it started to feel like we were just going through the motions. It was creative claustrophobia.” And so the band, at its peak, unceremoniously broke up.

“We were just dumb kids. We had no idea what we were doing with our little garage band. Looking back, that may have been the worst decision of my career. But when you’re young and dumb, you don’t realize that; you just think ‘Well, I’ll just do the next thing that comes along.’”

Today, Henry & June is fondly recalled as an early part of the Detroit music resurgence of the latter 20th Century. While The White Stripes, Kid Rock, The Detroit Cobras, and various Detroit rappers, from Eminem to Insane Clown Posse, put the Motor City musically back on the map, Henry and June remains a small part of that legacy. Copies of “Going Back to Memphis” routinely go for more than $100 on eBay, and the song was recorded live by The White Stripes for their DVD concert film, Under Blackpool Lights.

And no, Wilson hasn’t received any royalties. It all worked out for the members of Henry & June, though. Drummer Ben Swank is now the top A&R guy at Third Man Records, Jack White’s label. The band did a well received reunion back in 2010 in Toledo and everyone is still cool with one another. But in rock-n-roll and the blues, time waits for no one, so Wilson was off to new projects and new adventures.

And those adventures would lead to him nearly lose his mind.

On a wing and a Boogloosa Prayer

Brushing off the ashes of Henry & June, Wilson decided to further buckle down and get more “authentically bluesy.” He quickly formed a new band with Ben Swank and guitarist Todd Albright, that went through various names such as Dime Store Glam and Gin Mill Moaners. They sat in for many nights at the long-gone-but-never forgotten Rusty’s Jazz Cafe.

“I was spending all of my disposable income on that watered down whiskey at Rusty’s,” said Wilson. “Rusty’s was an amazing little place.” After a while though, he got restless and decided he would get as real as the blues could get and move to New Orleans.

“I wanted to see if I could live as a street performer,” said Wilson. “I had this rather naïve idea that I could possibly make a living at it in that town. I suspected it was the place on Earth where you might encounter people doing this kind of music.”

So Wilson moved to New Orleans, virtually homeless, busking on the streets of NOLA. Meanwhile, The White Stripes were starting to get their first big taste of international notoriety and began introducing “Going Back to Memphis” to a whole new audience due to their frequent covering of the song in live gigs.

“There I am trying to get lunch money down in New Orleans, and suddenly The White Stripes and the whole Detroit thing started to blow up and I’m trying to be Mr Authenticity down in effing New Orleans,” says Wilson, shaking his head incredulously. “My career is awful. I always zig when I should have zagged.”

But New Orleans proved to be an artistically fruitful time for Wilson. He met true, dyed-in-the-wool blues players who were playing incredible music from their souls. Nobody had record deals or anything that could get in the way of making direct, honest music. Many of these men and women were homeless or living off the grid; something Wilson describes as “an anti-American dream.” He talks enthusiastically and excitedly about that time in his life.

“These were some of the greatest living blues artists. There was a guy named Augie Junior who was simply incredible. I had never heard anything like him. There was this woman named Lisa Driscoll who played the washboard. People called her Ragtime Annie. And…”

Suddenly Wilson stops in mid-sentence and a hollow expression crosses his face. He stands up, sets his coffee cup down, excuses himself with a hurried “I’m gonna step out for a minute” and before uttering another word, he’s left the Glass City Cafe. A few minutes pass and he returns, wiping his forehead.

“I’m sorry,” he apologizes, sitting back down. “It’s just…it’s hard talking about this. I just got a little overwhelmed talking about some of my departed friends.”

He steadies himself with a sip of coffee that’s starting to go cold, as he’s eager to move on to talk about his other great band, Boogaloosa Prayer. Formed after moving back to Maumee fresh off a year in New Orleans, Boogaloosa Prayer, which Wilson says “was one of the best things I ever did artistically” came after stints in short lived bands like The Young Lords, and The Staving Chain.

Boogaloosa Prayer, an aggressive blues rock outfit featuring in part his old friend Jimmy Danger and Maumee drumming legend Todd Swalla, garnered quite a devoted following, playing in both Toledo and Detroit. The band had momentum behind them that recalled the Henry & June days. Then one hot summer night in 2006 at the now-shuttered Mickey Finn’s Pub, Wilson’s demons got the better of him.

Sporting a shaved head and a sickly frame that was skinny even by his normally lithe, sinewy standards, Wilson cracked onstage during the show. He ranted incoherently, couldn’t perform any songs, and couldn’t remember any lyrics. To everyone who was there, it was a harrowing experience.

Today, Wilson is reluctant to talk about the incident but he acknowledges it happened.

“I can say that I had a horrible psychotic breakdown and it had an impact on my life,” says Wilson, a bit guardedly. “At the time I had several severe emotional stressors in my life. A toxic woman in my life was stalking me. I had a business deal that was crushing me under the pressure. Plus, Boogaloosa Prayer was breaking up at the time because Swalla was moving to California. It all led to that time in my life.”

Following his breakdown, Wilson spent some time in a psychiatric ward, and lived in his aunt’s attic as he attempted to rebuild his fragile psyche. He eschewed traditional psychotherapy and refused meds because he’d seen too many of his friends “get hooked on those damned things.” Through a lot of hard work, meditation, and support from his friends, Wilson says he “totally got well again” and he hasn’t had any mental health issues since— thank goodness.

“Losing your sanity really puts a damper on your life.”

Still walkin’ down that road…

Wilson now lives in what he calls “a shack,” though it’s actually a carriage house out on a property in Maumee. The place smells of incense, a bit cramped but cozy abode, filled with guitars, amps, books on Buddhism, and novels by Charles Bukowski. Exactly how you would expect Wilson to live. This is not the living quarters .of a typical 45 year old, but it is definitely the home of a bluesman— and that’s all Wilson ever wanted to be. He plays gigs around the region and works as a “factotum” (his term) helping out family members and friends with projects. He’s completed an album and is currently trying to figure out how to release it. Love? Not interested.

“I have the kind of personality where I just do better alone,” he says simply. He may be alone but he’s not lonely. He has the best friends in the world in his life, even if most of them are dead. Son House. Sonny Boy Williamson. Bo Carter. All those great blues artists of yesteryear he counts as his personal friends, and by playing their music and his own songs inspired by their influence, Wilson is a happy man.

On that cold December day at the Glass City Cafe, Wilson utters a line that captures his essence: “Oh, I’m Dooley Wilson. Don’t mind me.” But, about that, he’s wrong. Mind him. Pay attention to Dooley Wilson. Pay close attention.

Post navigation

< PREVIOUS POST

N

1 note

·

View note