#is there any way of describing this concept that isn't a piece of pop culture

Text

you ever notice how many greek myths aren’t nearly as famous for what they did as for how they were punished? sisyphus, tantalus, cassandra... heck, even prometheus is almost half as well known for having his liver eaten as for stealing fire, and somehow that managed to overshadow literally creating humanity.

#mythology#greek mythology#sisyphus#tantalus#cassandra#prometheus#law and order#crime and punishment#is there any way of describing this concept that isn't a piece of pop culture

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Originality, Criticism, and Entitlement

After joining the IF community, I've come to see (and experience) the accusation that there are IF writers who steal, copy, or even plagiarize another author's work. I'm going to explain why throwing such accusations around is harmful not only to the accused, but the community as a whole.

This is also an explanation as to why they're incredibly stupid criticisms, and unless there is actual, direct evidence that the work is being copied or stolen, it is not, as such "critics" want to call it, "ripping off" anybody.

(Long read)

Star Wars (1977) is considered by many to be the world's first real blockbuster, with such sensation and hype that even over thirty years since its original release date, it reminds a key figure in our pop culture and media today. In every form or fashion, Star Wars was groundbreaking in terms of cinematic storytelling and movie-going experience.

But Star Wars is nothing new.

George Lucas, the creator, has discussed many times over the years just how precisely the world of Star Wars came to be, and its origins go back much, much farther than you think.

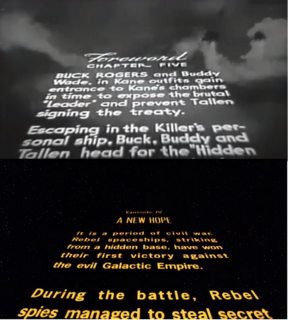

George Lucas claimed that the idea of Star Wars was inspired by Flash Gordon serials, a comic book series that was turned into a TV show in the 1930s. The famous title crawl that appears at the beginning of every Star Wars movie?

Look familiar?

It is also a pretty well known fact that the Galactic Empire and Rebels, along with the battle scenes within the movies, also take heavy inspiration from WWII. Stormtroopers are German Gestapo, the X-Wings and TIE Fighters are inspired by WWII aerial combat: https://youtu.be/msb8OdvBBjU

There is a clear right and wrong that is written into the Star Wars universe, and that most assuredly comes from the material and real world events that George Lucas was inspired by; serial comics and shows of the 30s, 40s, and 50s, leaned heavily into black and white morality. This is why superheroes from that era like Superman or Batman were originally written as static characters. "Superman is invincible, that's not as interesting as the X-Men struggling with their place in society!" Well, yeah, that's because Superman was meant to be nothing more than a comic book character that allows children to act out their power fantasy- "you can't make me go to bed, mom! Superman doesn't go to bed!" etc. etc.

But Star Wars has inspiration that goes back even further than the 1930s. It goes back to ancient Mesopotamia.

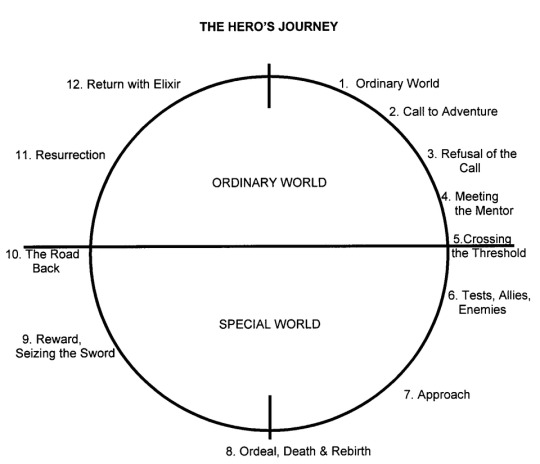

The Epic of Gilgamesh is the world's oldest and most notable form of literature that we know of. It is an epic that describes the heroic journey of one Gilgamesh, told in five parts. This is the earliest known example of what is known as "The Hero's Journey" in literature.

If you have any knowledge of the first movie of Star Wars, you're well aware of the story beats that you can read out in this diagram, as well be able to distinguish the similarities it has with The Epic of Gilgamesh.

Does this mean that Star Wars ripped off The Epic of Gilgamesh?

No. It doesn't. Because even though the story shares similar story beats, and features a black-and-white morality, a sci-fi space opera is a far cry from ancient Mesopotamian gods battling with each other. George Lucas didn't read the epic in school and decide "ah ha! I know how I'm going to make money!"

He was inspired, and he took that inspiration and created a multi-billion dollar franchise that millions love across the globe. He wrote that story and directed that movie, he put in the blood, sweat (lots of sweat- they filmed in Tunisia) and tears to make something WHOLLY NEW, and yet in some ways...similar.

Humans are very complex creatures, and our brain loves nothing more than finding patterns in things. Why is there such a thing as the Rule of Three in literature, a rule that dictates the satisfaction the reader gets when a story has a plot that occurs in three parts? Why is there traditionally only three acts? It is, simply put, satisfying. This traditional three-part structure often times creates stories that may look or feel similar simply because of how it is structured. This is not copying. This is a literature technique that humans have been using since the beginning of language itself.

And this is why I have such a problem with the people suggesting that authors are "copying" popular works- no one solely invented story beats, no one invented the supernatural fiction, no one, singular person, solely created the concepts that we are using today. No one. Not a single thing written is wholly original.

Originality is overrated. We are products of our environment, our culture, our media we consume- if an IF writer has a story with vampires and other supernatural creatures, and the MC is a detective attempting to solve crimes, was that invented by the very popular Wayhaven Chronicles by Mishka Jenkins? No. Vampires in media are nothing new, detectives in media are nothing new, and if they so happen to exist in other stories, what of it? Did Mishka invent vampires? No. They're a cultural phenomenon that has existed in multiple civilizations at once. Did she invent detectives? Obviously not.

Mishka was inspired and so were countless of other IF writers to write a story that involved the supernatural. These IF writers may have similar story beats, they may have similar themes, but that does not make it copying.

You know what makes Star Wars or The Wayhaven Chronicles or any other form of entertaining media great? Innovation.

It is how the authors tell the story, and why it is being written that creates such vast differences in genres. Star Wars isn't The Epic of Gilgamesh because its just "in space", it is the magnificent, innovative storytelling behind Star Wars that makes it so unique in our minds. The cinematography, the storytelling, the dialogue, the acting- all of that hard work into making something worthwhile and good is what makes it so unique when comparing it to other media that feature the literary use of "The Hero's Journey".

We all have something to bring to the table, to tell our stories that have a piece of us inside them. They are influenced by our laughter, our tears, our horror, our love, our rage or terrible indifference. They are influenced by our passions, our delusions, and they are written because we wish it to be so.

Are all impressionists copying Monet because he popularized impressionism? Are all artists who paint in similar styles copying off of the one who created the style in the first place? No. They're not.

To accuse IF authors, particularly the INNOCENT ones of copying others is an unbelievably insulting and ignorant statement that disregards the author's creativity and free will to write whatever the hell they want. If all you have to see out of a story is the basic, bare bones elements to it, then allow me to speak for all IF authors out there and say:

You're missing the fucking point!

We've all put our hard work into not only LEARNING a coding language (which, surprise, not ALL of us know and have to spend HOURS figuring out) but we've learned a coding language to create a game for other people to enjoy, and we'll be damn fucking lucky if we're able to get any money off of our work that we have put in it.

This criticism becomes a form of entitlement real fast, as if a reader has any say as to the pace or way an IF story (or any art for that matter) is written.

Most of us are doing this because we love the idea of putting our work out there as an IF fiction for fun. Some of us have to work jobs, some of us have complicated lives that demand constant attention, some of us wish to do this as a living, but all of us?

All of us deserve the courtesy of being a creator that is sharing their work with the world.

The next time you decide to accuse an IF writer of copying another person, ask yourself if it's legitimate plagiarism or you're just someone who doesn't have the capacity to consider that literary themes, tropes, cliches, and genres, are not the same thing as "copying".

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stan the Man

Since the news of Stan Lee's death I've wanted to write something meaningful about my own feelings for him, what he represented to me as a creator and as a human being, and what kind of impact his life had on my life. For many reasons (I was dislocated by the Woolsley Fire and haven't fully settled down since our return) I haven't had a chance to give such an in-depth appraisal much thought. Honestly, I doubt I could do a full appraisal of Stan's importance in my life even under the best of circumstances. His work and presence as an icon and as a human being helped form who I am today. To write a full appreciation of Stan I'd have to write my autobiography.

Among my most vivid childhood memories is my discovery of the Fantastic Four with issue 4, the first appearance of the Sub-Mariner. I was nine years old, and I'd been a comic book reader for years at that point. I knew about Superman, I knew about Batman, I'd read the early issues of Justice League. I was a compulsive reader, voracious (still am)-- devoting hours a day to books and stories and comics and even my parents' newspapers. (Both my parents were avid readers. My dad read science fiction, my mom loved mysteries.) I vividly recall the astonished joy I felt when my mom took me to our local library and got me my first library card. I was six, I think, and the reality of a roomful of books just for kids seemed like a gift from heaven. I won all the reading awards at school-- any competition for reading the most books in a year was over as far as I was concerned the first week. By nine, I'd already graduated from "age appropriate" books for pre-teens to Heinlein's juveniles, Asimov's robot stories, and the collected Sherlock Holmes stories of Arthur Conan Doyle. I was a total reading nerd.

And then came Fantastic Four.

I've never been hit by lightning but I have to imagine the shock might be similar to what I experienced reading that early adventure of Reed Richards, Sue Storm, her kid brother Johnny, and Ben Grimm. If you weren't a comic book reader at that time you cannot imagine the impact those stories had. There's nothing comparable in the modern reader's experience of comics-- nothing remotely as transformative. (To be fair, I suppose both "The Dark Knight Returns" and "Watchmen" come close, but both remarkable works built on prior tradition and were perhaps a fulfillment of potential and creative expectations. The Fantastic Four was _sui generis_.) Over a series of perhaps five issues, a single year, Stan and Jack Kirby transformed superhero comics in an act of creative alchemy similar to transmuting lead into gold, and just as unlikely.

They also changed my life. Because Stan credited himself as writer and Jack as artist, he opened my nine year old eyes to a possibility I'd never really considered before: I could be something called a comic book "writer" or "artist."

Think about that, for a moment. Before Stan regularly began giving credits to writers and artists, comics (with a few exceptions) were produced anonymously. Who wrote and drew Superman? Who wrote and drew Donald Duck? Who wrote and drew Archie? Who knew? (Serious older fans knew, of course, but as far as the average reader or disinterested bystander knew, most comics popped into existence spontaneously, like flowers, or in some eyes, weeds.)

Stan did more than create a fictional universe, more than create an approach to superhero storytelling and mythology-- he created the concept of comic book story creation itself. Through his promotion of the Marvel Bullpen, with his identification of the creative personalities who wrote and drew Marvel's books, he sparked the idea that writing and drawing comics was something ordinary people did every day. (Yes, yes, to a degree Bill Gaines had done something similar with EC Comic's in-house fan pages, but let's be honest, EC never had the overwhelming impact on a mass audience that Marvel had later.) He made the creation of comic book stories something anyone could aspire to do _as a potential career_.

That's huge. It gave rise to a generation of creative talent whose ambition was to create comics. Prior to the 1960s, writing and drawing comic books wasn't something any writer or artist generally aspired to (obviously there were exceptions). Almost every professional comic book artist was an aspiring newspaper syndicated strip artist or an aspiring magazine illustrator. (Again, there were exceptions.) Almost every professional comic book writer was also a writer for pulp magazines or paperback thrillers. (Edmond Hamilton, Otto Binder, Gardner Fox, so many others-- all wrote for the pulps and paperbacks.) Comic book careers weren't something you aimed to achieve; they were where you ended up when you failed to reach your goal.

Even Stan, prior to the Fantastic Four, felt this way. It's an essential part of his legend: he wanted to quit comics because he felt it was stifling his creative potential, but his wife, Joan, suggested an alternative. Write the way you want to write. Write what you want to write. Write your own truth.

He did, and the rest, as the saying goes, is history.

When I picked up that issue of Fantastic Four, I was a nine year old boy with typical nine year old boy fantasies about what my life would be. Some were literal fantasies: I'd suggested to my dad a year or so earlier that we could turn the family car into the Batmobile and he could be Batman and I could be Robin and we could fight crime. After he passed on that idea I decided we could be like the Hardy family-- he could be a detective and I could be his amateur detective son, either Frank or Joe. Later I became more realistic and figured I could become an actor who played Frank or Joe Hardy in a Hardy Boy movie. In fact, by nine, my most realistic career fantasies involved either becoming an actor or an astronaut, and of the two, astronaut seemed like the more practical choice.

Stan and Marvel Comics gradually showed me a different path, a different possible career. By making comic books cool, by making them creatively enticing, and by making the people who created comics _real_ to readers-- Stan created the idea of a career creating comics.

Stan alone did this. We can argue over other aspects of his legacy-- debate whether he or his several collaborators were more important in the creation of this character or that piece of mythology-- but we can't argue about this. Without Stan's promotion of his fellow creatives at Marvel there would have been no lionizing of individual writers and artists in the 1960s. Without that promotion there would have been no visible role models for younger, future creators to emulate. Yes, some of us would still have wanted to create comics-- but I'd argue that the massive explosion of talent in the 1970s and later decades had its origin in Stan's innovative promotion of individual talents during the 1960s.

Nobody aspires to play in a rock band if they've never heard of a rock band. The Marvel Bullpen of the 1960s was comicdom's first rock band.

That was because of Stan.

For me, Stan's presence in the world gave direction and purpose to my creative life, and my creative life has given meaning and purpose to my personal life. I am the man I am today, and I've lived the life I've lived, because of him. From the age of nine on, I've followed the path I'm on because of Stan Lee. (So much of my personal life is entangled in choices I've made as a result of my career it's impossible for me to separate personal from professional.)

My personal relationship with Stan, which began when I was seventeen years old, is more complex and less enlightening. It's a truism your heroes always disappoint you, and I was often disappointed by Stan. Yet I never stopped admiring him for his best qualities, his innate goodness, his creative ambition and unparalleled instincts. People often asked me, "What's Stan really like?" For a long time I had a cynical answer, but in recent years I realized I was wrong. The Stan you saw in the media was, in fact, the real Stan: a sweet, earnest, basically decent man who wanted to do the right thing, who was as astounded by his success as anyone, and who was just modest enough to mock himself to let us know he was in on the joke. I imagine Stan was grateful for the luck of being the right man at the right place at the right time-- but it's true he _was_ the right man. No one else could have done what he did. The qualities of ego and self-interest that I sometimes decried in him were the same qualities needed for him to fulfill the role he played. In typical comic book story telling, his weaknesses were his strengths. And his strengths made him a legend and a leader for all who came after him-- particularly me.

This has been a rambling appreciation, I know. Scattered and disjointed. Like I said, trying to describe the impact Stan had on my life would require an autobiography.

When I started thinking about Stan in light of his death I realized, for the first time (and isn't this psychologically interesting?) that Stan was born just a year after my father. When I met him, as a teenager struggling with my own father as almost all teenage boys do, Stan probably affected me as a surrogate father figure. Unlike my own father, Stan was a symbol of the possibilities of a creative life. He was a role model for creative success, like other older men in my life at the time. But unlike them, he'd been a part of my life since I was nine years old. A surrogate father in fantasy before he partly became one in reality.

Now he's gone. Part of me goes with him, but the greater part of me, the life I've led and built under his influence, remains.

Like so much of the pop culture world we live in, I'm partly Stan's creation.

'Nuff said.

309 notes

·

View notes