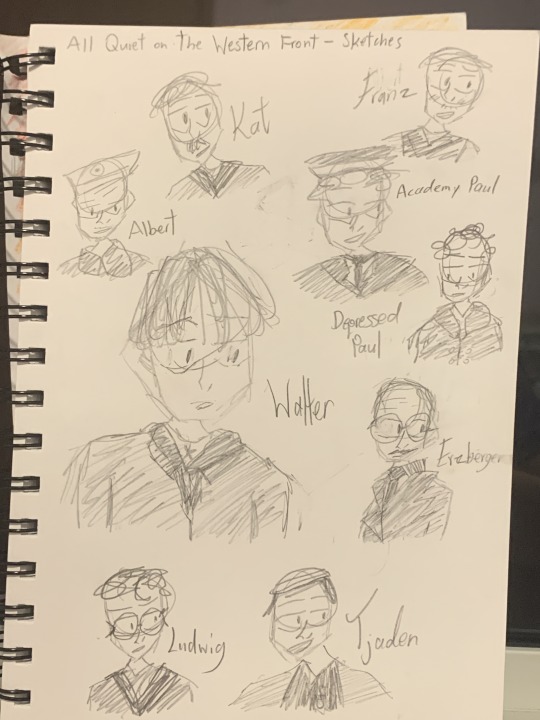

#ludwig behm

Text

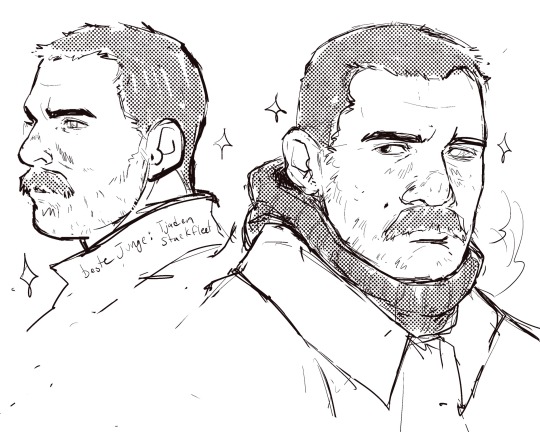

baumer and friends

#my art#all quiet on the western front#aqotwf#im westen nichts neues#paul baumer#stanislaus katczinsky#tjaden stackfleet#franz muller#ludwig behm#albert kropp#AND THATS EVERYONE. from the movie lol#these r unfortunately pretty bad but i’ve been busy and also kind of rotting so everything i touch is cursed#hello wednesday night crowd#wait. no it’s tuesday. idk where i am

661 notes

·

View notes

Photo

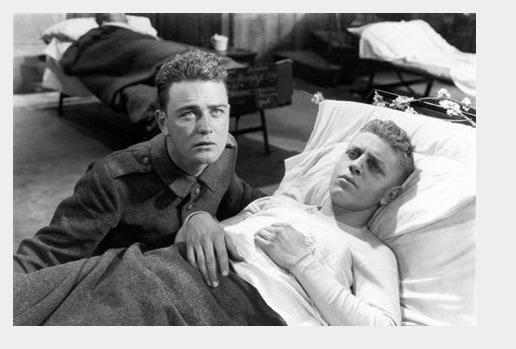

"I can't do this, Paul. I can't do this. I need to go home."

All Quiet on the Western Front (2022)

#all quiet on the western front#im westen nichts neues#paul baumer#felix kammerer#ludwig behm#adrian grunewald#daniel bruhl#oscar 2022#movie edit#films edit#cinema edit#germany#mygifs

361 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albrecht Schuch and Edin Hasanović being cuties during the premier of All Quiet on the Western Front

Bonus:

Felix cute waving ~

The Boys (TM) looking dandy in their outfits!

#albrecht schuch#edin hasanovic#felix kammerer#jakob schmidt#aaron hilmer#moritz klaus#all quiet on the western front#im westen nichts neues#paul bäumer#stanislaus katczinsky#albert kropp#frantz Müller#adrian grünewald#ludwig behm#tjaden stackfleet#germany#erich maria remarque#gif#oscars#2023#german actor#period movie#period drama#world war 1#premier#berlin#netflix

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

you guys got any headcanons on the friend group (Paul, Kat, Albert, Tjaden, Franz, and Ludwig) if they were in modern times???

#All Quiet on the Western front#paul baumer#stanislaus katczinsky#albert kropp#tjaden#franz muller#ludwig behm

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

hear me out.

the all quiet boys as modern aesthetics (including 1930/1979 characters too)

paul: i feel like he'd be kinda alt and cottagecore at the same time

kat: daddy. christian grey

tjaden: streetwear. i wanna see him in a cute sweater and cargo pants

franz kemmerich: cottagecore do i need to explain this

leer (1979): EBOY EBOY. TIKTOK EBOY HAHA

ludwig: soft boy :)

franz müller: i don't know why but i feel like he'd pull off military but casual. like the army shirts and boots but as a casual style

albert kropp: 60s. this was an impulse but just imagine him dressed like a mod boy <3

#all quiet on the western front 1930#all quiet on the western front 1979#all quiet on the western front 2022#all quiet on the western front#all quiet movie#im westen nichts neues#paul bäumer#franz kemmerich#stanislaus katczinsky#tjaden stackfleet#albert kropp#franz müller#leer (1979)#ludwig behm#modern au#aesthetics

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

walter’s the new recruit’s name btw

#all quiet on the western front#tjaden#ludwig behm#matthias erzberger#walter#paul baumer#albert kropp#stanislaus katczinsky

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I AM DYING OMG. I AM GOING TO SEE ADRIAN GRÜNEWALD LIVE ON STAGE OMG BABY BOY Q_Q

#my poor boy#all quite on the western front#ludwig behm#adrian grünewald#der theatermacher#aqotwf#berliner ensemble

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#all quiet on the western front#behind the scenes#AQOTWF#amazing cast#albrecht schuch - stanislaus katczinsky#moritz klaus - franz müller#felix kammerer - paul bäumer#aaron hilmer - albert kropp#adrian grünewald - ludwig behm#edin hasanovic - tjaden stackfleet#wonderful picture#im westen nichts neues#erich maria remarque

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

1918

by Cherry_trii

The German pilot crashes but, this time, he doesn't quite succeed on killing Blake. Now Schofield has to deal with a scared German boy, an injured Blake, and on top of that has to make sure the other German pilot doesn't come down and finishes the job.

Words: 1024, Chapters: 1/?, Language: English

Fandoms: Im Westen nichts Neues | All Quiet on the Western Front (2022), 1917 (Movie 2019)

Rating: Teen And Up Audiences

Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings, Graphic Depictions Of Violence

Categories: Gen, M/M

Characters: William Schofield, Tom Blake, Paul Bäumer, Stanislaus Katczinsky

Relationships: Tom Blake/William Schofield, Paul Bäumer/Ludwig Behm (implied)

Additional Tags: Emotional Hurt/Comfort, Alternate Universe - Canon Divergence, Alternate Universe - Everyone Lives/Nobody Dies, Stabbing, Father-Son Relationship, Crying, Tags May Change, Feelings Realization, Implied/Referenced Homophobia

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

All Quiet on the Western Front (2022, Germany)

As a film buff, I retain a preference to reading a book first before seeing its adaptation. But with how many movies I see in a year – sometimes not realizing that a movie is a literary adaptation before starting it – and given how many original source materials are out-of-print or little-read (let alone how slow a reader I am), this is often too difficult a proposition. I make an attempt, however possible, to learn about the themes of an adapted book I was not able to read before heading into a film write-up. Strict fidelity to the text is not a requirement; yet a film adaptation should adhere to the spirit of the text. Any significant changes to that requires the change be done with artistic intelligence and sensitivity. Especially when the adapted book in question is significant in a peoples’ or a nation’s consciousness. Published in 1929, All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque is a landmark novel in anti-war literature and remains – for its depiction of World War I on the bodies and minds of the young men sent to fight it – an important part of modern Germany’s sociopolitical identity.

Lewis Milestone’s 1930 film adaptation at Universal with Lew Ayres was the first cinematic masterpiece following the introduction of synchronized sound and the era of the silent film. Now steps in Edward Berger’s German-language adaptation for Netflix, starring Felix Kammerer, in hopes of reminding viewers that Im Westen nichts Neues (roughly “Nothing New in the West”) is, despite its universal appeal, fundamentally a German story. Berger’s All Quiet is a stupendous technical masterpiece – harrowing visual and sound effects, overflowing with blood and mud. It is among the most technically accomplished war movies this side of Saving Private Ryan (1998). Along the way, Berger’s All Quiet tries for too much, and betrays the characterizations and the intent of Remarque’s novel. With some of its violent scenes shot too aesthetically pleasing alongside an offensive and disrespectful electronic score, 2022’s All Quiet casts the French civilians and soldiers as “the enemy” rather than fellow victims. It veers perilously close to fetishizing the violence within.

Before a brief synopsis, it seems appropriate to reproduce Remarque’s epigraph to All Quiet on the Western Front here:

This book is to be neither an accusation nor a confession, and least of all an adventure, for death is not an adventure to those who stand face to face with it. It will try simply to tell of a generation of men who, even though they may have escaped shells, were destroyed by the war.

It is 1917, and the Great War has been plodding along for three years. Along with his friends Ludwig Behm (Adrian Grünewald), Albert Kropp (Aaron Hilmer), and Franz Müller (Koritz Klaus), student Paul Bäumer (Kammerer) enlists in the Imperial German Army. They all receive uniforms that, unbeknownst to them, belonged to German soldiers killed in action. Skipping almost entirely over basic training, Paul and his friends deploy to the Western Front, on the French side of the Belgium/France border. There, they befriend Stanislaus “Kat” Katczinsky (Albrecht Schuch) and Tjaden Stackfleet (Edin Hasanovic), who are several years older and have been fighting since close to the war’s beginning. These young men muddle on in drenched trenches, freezing weather, and their comrades’ horrific deaths. Parallel to the plight of Paul and his fellow soldiers is German politician Matthias Erzberger (Daniel Brühl), who secretly travels by train to the Forest of Compiègne to negotiate with French General Ferdinand Foch (Thibault de Montalembert) an armistice.

Also featuring in this film are Devid Striesow as the so-villainous-he-must-be-a-moustache-twirler General Friedrichs, as well as Andreas Döhler and Sebastian Hülk as two German officers.

This All Quiet on the Western Front occasionally frames its violent scenes as too painterly, the combat infrequently choreographed too closely to action movies (e.g., 2017’s Dunkirk is sometimes more of a suspense movie than it is a war movie and Sam Mendes’ 1917 from 2019 is an aesthetic challenge and action movie first, war film second). The opening moments are a dolly shot that linger over a patchwork of corpses strewn about No Man’s Land, with the dull rattle of machine gun fire occasionally disturbing the soil. There is an almost gawking approach to how cinematographer James Friend hovers over the bodies. One character’s death is shrouded in a blinding angelic light – applying too picturesque a technique for a non-fantastical moment. Some exceptions to this voyeuristic, perhaps fetishistic approach to framing warfare appears, including the frightening emergence of French tanks through a cloud of gas. Berger succeeds in displaying war for all its brutality. The film’s sheen, however, comes off as too aggressive and its camerawork reflecting a Netflix-esque polish.

The most glaring misstep from the screenplay by Berger, Ian Stokell, and Lesley Paterson is to include any perspectives not involving Paul and his most immediate comrades. Depicting the insights of Erzberger, Foch, and the fictional General Friedrichs removes one of the central pillars of why All Quiet on the Western Front was such a revolutionary piece of literature. Remarque’s novel, at a time when “anti-war” narrative art was in its infancy, was one of the first war narratives that concentrated entirely on common soldiers – not the officers that commanded them or the politicians that guided them.

Before focusing on Paul and his friends, let us get the officers and politicians out of the way first. The insertion of the armistice negotiations and Gen. Friedrichs’ beliefs over politicians selling the Germany army out – more on this fiction shortly – stunts Paul and his friends’ respective character growths. And despite a decent performance from Brühl, these scenes (except for the final time the elite appear) play out repetitively: Erzberger pleads to Foch for a ceasefire, Foch demands a conditional surrender that will heavily punish Germany, and Erzberger mulls over the terms of surrender. This is all distracting from the common soldiers’ experiences, and provides as much cinematic or educational value as an amateur historical reenactment.

Berger’s stated justification for including these scenes – and letting them drag on too long in the film’s second half – is reasonable. Over the last decade, the actions of far right political groups in Germany have become more visible. These contemporary groups espouse the myths that some in 1920s and ‘30s Germany used to justify the nation’s actions leading up to World War II – all which monolithized and exploited German WWI trauma to serve repugnant purposes. The emotional imbalance of the Erzberger*/Foch scenes paints France and the Allies as an unforgiving “other”, as well as the war’s eventual “victors” (the Allies did prevail in WWI, but Remarque sees no winners in warfare). For a work never meant to be an accusation and written in between the World Wars, the proto-fascist Gen. Friedrichs spits out an early form of the stab-in-the-back conspiracy theory‡. His behavior and appearance, eerily reminiscent of Allied propaganda of Germans as “the Hun”, casts him as the film’s obvious villain. These decisions all provide Berger’s All Quiet with a juxtaposition of morality more appropriate in a WWII movie than one for the Great War.

Beyond the implications of historical morality, Berger, Stokell, and Paterson’s screenplay undermines, at almost every juncture, Remarque’s critiques of the nationalism that began World War I. The decision to have Paul and his friends join the military in 1917 rather than 1914 (as it is in the book) makes it more difficult to have Paul and his friends to have conversations about the nature and the origins of this war. Instead, the screenplay keeps such dialogue to a minimum. As a result, Berger relies on cinematographer James Friend (in his first motion picture of note) to show us close-ups of Paul’s face to reveal his thoughts. In his film debut, Felix Kammerer is doing all he can with his facial and physical acting, but after a certain point this take on Paul results in him being an empty vessel.

Indeed, in Remarque’s book, Paul Bäumer is very much a reactive rather than proactive character. But that does not mean he is without deep introspection, as he is in this 2022 adaptation. Rather than someone who slowly realizes the nationalistic folly of WWI (“We loved our country as much as they; we went courageously into every action; but also we distinguished the false from true, we had suddenly learned to see.”), muses on how wars begin, and is anything but resigned to war’s inevitability, Kammerer’s Paul emotes and says nothing about these aspects of the war. Any critique from nationalism comes not from Paul in this adaptation, but from Gen. Friedrichs’ cartoonishly villainous behavior and Paul’s teachers in the film’s opening minutes. Paul and his friends are no battlefield geniuses, nor are they intellectuals. But the monotony of war – in the absence and presence of violence – grants them knowledge no classroom can give, wisdom that no elder can impart.

Berger, Stokell, and Paterson have the gall to delete entirely arguably the most critical passage in the book: Paul’s return home after being granted time for rest and recreation. After a lengthy spell fighting in the trenches, Paul’s leave completes his development as a naïve and adventure-seeking student to a detached, disillusioned man. Nationalism manipulates his father and others – mostly older men – into believing the justness of the conflict, that serving one’s country in warfare is glorious.

By contrast, Lewis Milestone’s 1930 adaptation takes Paul’s reunion with his teacher a step further than the book. In that version, instead of a chance encounter at a parade ground, Paul visits his teacher during class, with his newest students a rapt audience. The scene that follows is not subtle. But in the context of Milestone’s adaptation, the film earns it. As Paul, Lew Ayres refuses to gift his former teacher the heroic narrative he requests – paraphrasing Horace, decrying nationalism, and simply stating: “We try not to be killed; sometimes we are. That’s all.” One figures these are the words, delivered in sullen fury, by WWI’s veterans. Berger’s adaptation again leans too heavily on Kammerer to relate any semblance of the above ideas. There is no analogue scene to juxtapose the behavioral and psychological differences between battlefront and homefront, no character or even a faraway figure for Paul to verbally challenge. Kammerer’s Paul does undergo a behavioral and cognitive shift by the conclusion of 2022’s All Quiet. Yet, his transformation is not nearly as dramatic as the narrative needs it to be. These failures all stem from a screenplay that might as well have been titled something else. It is damningly incurious about Paul and his friends.

Major movie studio film scores are moving in a particular direction: amelodic, electronic, experimental, metallic, and minimalistic. It seems, by how awards voting bodies and audiences are reacting to such music, what I am about to write paints me more of an outlier than ever.

Composer Volker Bertelmann (also known as his stage name Hauschka; 2016’s Lion) concocts an anachronistic score that includes all these elements. Devoid entirely of recognizable melody (droning strings), Bertelmann’s score has one repetitive three-note idea – I refuse to call this a motif, as it lacks any sense of development from its first to final appearances – that damages and dominates the movie. Inserted in strangely timed moments and meant to intensify dread, Bertelmann’s idea begins from the root note (B♭), up a minor third (D♭), then descends a minor sixth (F). Bertelmann plays these three notes fortissimo, with synthesizer mimicking blaring brass – trust me, you know the sound and you may know its worst practitioners. When recurring underneath the strings, the idea modulates. Memorable as it may be, this metallic sound is more appropriate for hyping young men before a battle or at a rave rather than suggesting dread. Even worse: this is disruptive music. There is a healthy balance to when music should or should not accompany the imagery onscreen. One should notice music in a movie, and it should empower – but not completely overshadow – the emotions and ideas in respect to a certain scene. Bertelmann’s interruptions appear mostly in calms before the proverbial storms. These are the moments the characters and the audience should collect themselves before the killing restarts. Thus, his three-note idea abuses and instantly overstays its welcome.

Is there a place for such colorless, obnoxious, and offensively manipulative music in film? Certainly. Just not in anything entitled All Quiet on the Western Front.

On its surface, a German-language film adaptation of All Quiet on the Western Front would restore a cultural and linguistic authenticity to Remarque’s text, one of the most important literary works in German history. To some extent, Berger succeeds. His All Quiet is a technical wonder, but its human interest is nil. Remarque’s prose is not the most accomplished, but his subjective descriptions of trench warfare and his characters’ philosophizing in moments of boredom and quiet were unlike anything almost any Western reader ever encountered. We, the readers, grow alongside Paul and his friends. In 1930, the viewers saw a small group of friends – Milestone’s adaptation is unique in that Paul does not truly emerge as the main character until halfway through the film – see their youth and optimism pummeled away with each shelling and charge. A humanity remains, but tenuously. Berger’s adaptation treads an easier path by inserting a reenactment of the armistice negotiations and expediting Paul’s characterization by immediately dismantling his inwardness and sense of hope.

As a document of a generation’s experiences, a critique of that era’s nationalism that led to the conflict, and a common soldier’s processing of the war’s origin and purpose, this is a poor adaptation of Remarque’s novel. It clears the hurdle in anti-war narratives by decrying warfare as ugly. Beyond this basic expectation, it accomplishes little else.

My rating: 6/10

* Erzberger was assassinated by the far-right terrorist organization Organisation Consul (OC) in 1921. The group was disbanded the year after, but its former members were absorbed into the Nazi Party’s Schutzstaffel (SS).

‡ This conspiracy theory was primarily associated with Jews, but the Nazis also extended it to the political elite that negotiated the surrender. And as if it weren’t obvious enough, one of our German characters is stabbed in the back in the film’s concluding minutes.

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#All Quiet on the Western Front#Im Westen nichts Neues#Edward Berger#Felix Kammerer#Albrecht Schuch#Daniel Brühl#Aaron Hilmer#Moritz Klaus#Adrian Grünewald#Edin Hasanovic#Thibault de Montalembert#Devid Striesow#James Friend#Sven Budelmann#Volker Bertelmann#Hauschka#Lesley Paterson#Ian Stokell#Netflix#My Movie Odyssey

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character Changes in the 2022 Movie

So I’m pretty sure Ludwig Behm in the 2022 movie wasn’t in the book and was based off of Joseph Behm in the book. They both have the same glasses and last names. Also they both are the first to die among Paul’s friends. However Joseph never wanted to enlist unlike Ludwig and gets blinded and killed in no man’s land. Both of them are pretty similar in the end and make me and Paul feel very sad. :(

Tjaden’s character change is definitely the more noticeable as book Tjaden is a lot younger. He is Paul’s age but they were not school mates. He’s known in the book for being a big eater who loves food more than anything yet still manages to be as skinny as rake (He reminded me of Sasha from aot). He is laid back and humorous and so is the older Tjaden at times. Both also have serious sides as Tjaden is able to give a very insightful answers that explain the futility of war but he hides it under his usual comedy.

2022 Tjaden borrows parts of his character from Haie Westhus from the book. Haie was a peat digger the same age as Paul who loathes the job. This makes him want to be a military officer like Tjaden after the war. He dies when his back is injured fatally. 2022 Tjaden dies from a way that is inspired from the book. There is another injured soldier in the Catholic hospital Paul goes to, who attempts suicide with a fork after he learns that his leg had been lost. Unlike Tjaden he was stopped in time.

I didn’t think that I would like the older Tjaden very much because he was too unfamiliar but I enjoyed his character greatly. I loved seeing Kat have a friend his age and the actors chemistry was really good. His last scenes with Paul made me sob. He later felt like a natural addition despite me being a little weirded out at first and I feel bad not knowing that this version of Tjaden doesn’t exist in most forms of All Quiet on the Western Front.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

QUARTONAL

TRAUMGESTALTEN

"Traumgestalten" - canciones románticas a capella con el renombrado conjunto vocal Quartonal en Sony Classical.

Consíguelo AQUÍ

Cuatro hombres, cuatro voces, un sonido: Quartonal es uno de los conjuntos vocales más solicitados de Alemania desde hace más de 15 años. Y el repertorio de los cuatro cantantes del norte de Alemania abarca desde canciones corales clásicas y folclóricas hasta canciones pop y folclóricas internacionales. Para su tercer álbum para Sony Classical, Quartonal ha seleccionado canciones románticas y romanticistas de los siglos XIX y XX bajo el título "Traumgestalten". Se trata de poemas de Goethe, Heine, Eichendorff y Mörike, entre otros. Las canciones y baladas son de compositores tan importantes como Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy y Hugo Wolf. También hay canciones populares, algunas en arreglos modernos.

Temáticamente, las 15 canciones de "Traumgestalten" giran en torno a temas como el amor, el placer y la naturaleza. Felix Mendelssohn, por ejemplo, adaptó "Wasserfahrt" de Heinrich Heine a una pieza coral melancólica y al mismo tiempo oscilante. Wenzel Heinrich Veit (1806-1864) envolvió la famosa balada de Goethe "El rey en Thule" en una canción folclórica. Mathieu Neumann (1867-1928), por su parte, transformó el "Feuerreiter" de Eduard Mörike en una historia de terror musical.

SOBRE EL ARTISTA

El conjunto a capella Quartonal se fundó en 2006 y es uno de los grupos vocales más prometedores surgidos en Alemania en los últimos años. En 2010, los cuatro cantantes (Mirko Ludwig - tenor, Florian Sievers - tenor, Christoph Behm - barítono y Sönke Tams Freier - bajo) de Hamburgo ofrecieron una sensacional actuación de debut en el Concurso Nacional de Coros de Alemania, obteniendo el primer puesto en la categoría de Conjunto Vocal. Impulsados por su éxito en el concurso, Quartonal se embarcó inmediatamente en una apretada agenda de conciertos nacionales e internacionales. El álbum debut de Quartonal, "Another Way - English Vocal Music", se publicó en 2013 en colaboración con Sony Music. Su lanzamiento fue aclamado por la crítica y recibió elogiosas críticas.

Tras su éxito en el Concurso Nacional de Coros de Alemania, Quartonal cosechó una serie de aplausos en concursos de toda Europa. En 2012, Quartonal recibió los premios del público y del jurado en el concurso "A cappella" de Leipzig (Alemania) y en el concurso coral "Tolosako Abesbatza Lehiaketa" de Tolosa (España).

Las canciones también incluyen temas populares como "Ein Jäger längs dem Weiher ging" y "Die Gedanken sind frei" en nuevos arreglos. Entre las rarezas se encuentra una balada escrita por el compositor de origen polaco Joseph Kromolicki (1882-1961) sobre un texto de Justinus Kerner. Y los "Schilflieder" del compositor suizo Heinrich Sutermeister ponen de relieve cómo los compositores del siglo XX cultivaron el tono romántico. Cuesta creer que se compusieran en 1968.

La grabación fue una coproducción de SWR Kultur y Sony Classical.

"Traumgestalten" de Quartonal saldrá a la venta el 8 de diciembre a través de Sony Classical en CD y digitalmente.

0 notes

Text

said it before ill say it again. ludwig is the new all quiet's version of kemmerich. i love them both so much and it's so tragic that they both died so early on :(( i need to create a community for these gorgeous boys because ludwig and kemmerich deserved so much better

#small talk#rant post#all quiet on the western front#im westen nichts neues#all quiet movie#all quiet on the western front 1930#all quiet on the western front 1979#all quiet on the western front 2022#franz kemmerich#ludwig behm#adrian grünewald#george winter#ben alexander#justice for ludwig#justice for kemmerich#my boys :(#erich maria remarque

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

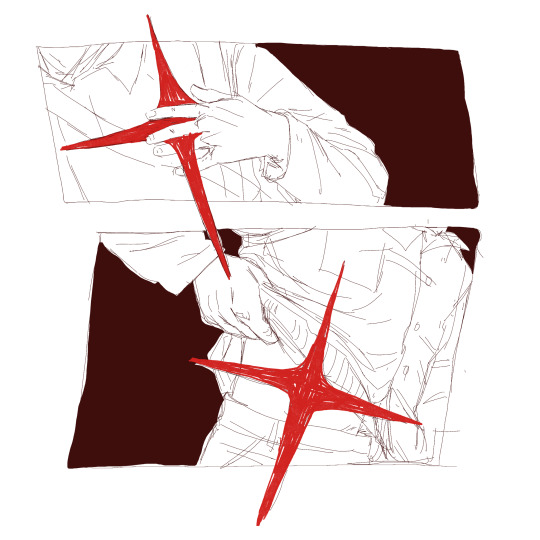

Could you please doodle Ludwig and Paul happy?

they be having fun doe

5 notes

·

View notes